You’re preparing for a meeting with a parent whose child has just received an autism diagnosis and must be ready to explain the services you will offer and the reasons why they will be effective. You have an extensive verbal repertoire for this, because intensive graduate training has taught you how to talk about these matters in precise, scientifically valid terms. Unfortunately, the parent did not attend graduate school in behavior analysis and does not have a similar verbal repertoire. What will you say? Just as importantly, what will you not say? How you choose to communicate could determine whether that family returns for many productive visits or seeks help elsewhere.

More than a dozen published articles by leading behavior analysts, spanning several decades, have suggested that our discipline’s specialized technical vocabulary can cause things to go awry when behavior analysts attempt to communicate with nonexperts (e.g., Bailey 1991; Doughty et al. 2012; Freedman 2015; Foxx 1990, Foxx 1996; Lindsley 1991). Nonexperts have occasionally validated these concerns (e.g., Berger 1973; Maurice 1993). One source of the problem, according to Foxx (1996); see also Lindsley 1991), is that the words behavior analysts have co-opted from everyday language to construct their technical vocabulary could mean something very different to the person on the street than they do to behavior analysts. In a tongue-in-cheek illustration of the problem, Foxx (1990) provided a glossary based on what he imagined nonspecialists might think when they hear behavior analysis terms. For example, Foxx defined extinction as “the disappearance of a species,” adding that this connotation, “can cause concern for parents when they are told, 'We would like to put your son, Jason, on extinction” (p. 95). If Foxx’s glossary captures anything of how real people perceive behavior analysis jargon, then communication issues may help to account for Maurice’s (1993) observation, based on her own long experience with various kinds of service providers that behavior analysts tend to come across to laypersons as “Attila the Hun” (p. 283).

The Problem: Unknown Relational Verbal Networks

Explained in terms of behavior principles, the communication problem may be one of relational networks. As Skinner (1957) noted, the “meaning” of verbal behavior is the sum of functional relations in which verbal responses are embedded. As the complexity of Skinner’s Verbal Behavior illustrates, in search of “meaning,” it can be difficult to reconstruct the historical circumstances under which a person’s verbal behavior has been emitted and the consequences that speaker and listener have experienced when it was emitted. Some insight into the relevant relational networks, however, can be derived from examining the verbal responses (e.g., words) with which a verbal response (e.g., word) of interest is commonly associated.1

Previously published concerns about repurposed terms (e.g., Foxx 1990) thus partially reduce to the likelihood that, for behavior analysts and the nonexperts with whom they try to communicate, the same verbal topography (i.e., word) may participate in very different relational networks. Those networks have not been systematically examined in traditional behavior analysis research. To date, all that may be said, based on a smattering of empirical studies, is that consumers appear to be less than enthusiastic about interventions that are described using jargon (e.g., Becirevic et al. 2016; Jarmolowicz et al. 2008; Witt et al. 1984).

A complementary line of research helps to provide the rationale for the present review and illustrates one specific way in which nonspecialists may respond differently to behavior analysis terms than behavior analysts presumably do. These studies draw on public domain data sets summarizing how members of the general public rate the emotional impact that individual words have on them (Critchfield et al. 2016; Critchfield and Doepke 2017; Critchfield et al. 2017a, b). Specifically, the data sets contain ratings, on a scale ranging from “Unpleasant” to “Pleasant,” for many of thousands of words, including some that double as behavior analysis terms. For instance, possibly commensurate with Foxx (1990) glossary definition, raters in one data set (Warriner et al. 2013) gave extinction a mean rating of 3.10 on a 9-point pleasantness scale (1 = most unpleasant, 5 = neutral, 9 = most pleasant). Such findings suggest that many behavior analysis terms really do strike people as less pleasant than English words on average, which suggests a need to choose words carefully when communicating with nonexperts.

The research just described has two limitations of present interest. First, it suggests only that nonexperts may regard behavior analysis terms as unpleasant. People say they find extinction to be unpleasant, for instance, but one can only guess why. Second, word-emotion corpora do not contain every behavior analysis term of interest (for instance, my colleagues and I have found no rating for operant or generalization). Until behavior analysts collect their own, discipline-specific data on relational networks that may be pertinent to the presumed communication problem, those seeking objective guidance on how to communicate (and not communicate) must rely on quick-and-dirty heuristics like consulting word-emotion databases.

A Convenient Source of Guidance: Visuwords®

Sophisticated experimental methods exist for studying the formation and structure of relational networks (e.g., Barnes Holmes et al. 2010; Barnes Holmes et al. 2000), but to my knowledge, they have not been applied to the problem under discussion. As a stopgap measure, those concerned with tailoring their communication to nonexpert audiences may consider consulting a free online tool called Visuwords® (http://visuwords.com). Consistent with the goal of mapping relational networks, the purpose of Visuwords®, according to its web site, is to allow users to “look up words to find their meanings and associations with other words and concepts.” Visuwords® relies on a database (WordNet®; e.g., Miller 1995) that

superficially resembles a thesaurus, in that it groups words together based on their meanings. However, there are some important distinctions. First, WordNet interlinks not just word forms—strings of letters—but specific senses of words. As a result, words that are found in close proximity to one another in the network are semantically disambiguated. Second, WordNet labels the semantic relations among words, whereas the groupings of words in a thesaurus does not follow any explicit pattern other than meaning similarity. (https://wordnet.princeton.edu/).

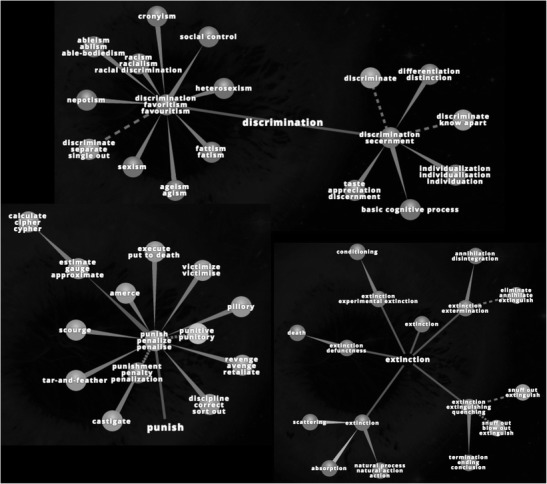

Thus, Visuwords® suggests not just that certain words are related but also how closely related they may be and what specific kind of relationship exists between them. The output is in the form of a network map linking the key word to other words and concepts. In the example output of Fig. 1, the distance between a target word and an associate is inversely related to closeness of association. A legend presented with each network (but omitted from Fig. 1) clearly indicates the part of speech represented by each word and the kind of relationship between any two words (e.g., synonym, opposite, part-to-whole, etc.).

Fig. 1.

Screen shots from Visuwords® of relational networks incorporating the behavior analysis terms discrimination, punish, and extinction. Distance between any two words inversely portrays closeness of association. The type of line connecting two words conveys the type of relationship uniting them, as explained in a legend that accompanies each network displayed in Visuwords® (for visual simplicity, the legend is not reproduced here)

It might be said that networks like those of Fig. 1 can remind behavior analysts of how certain verbal topographies functioned for them before intensive graduate training turned them into behavior analysts and thoroughly reconfigured their verbal repertoires. In this limited sense, that “stranger” sitting across the clinic table can be made to seem slightly less strange. For instance, upon examining associations in Fig. 1 (extinction with annihilation; punish with execute; and discrimination with favoritism), it is easy to grasp why nonexperts may have negative emotional responses to these technical terms (M pleasantness ratings of 3.10, 2.86, and 2.45, respectively; Warriner et al. 2013).

The implication is that, in interactions with nonexperts, some behavior analysis terms should be used judiciously due to the emotional/relational baggage that they carry. For some circumstances, Lindsley (1991) recommended avoiding potentially troublesome terms by using alternative phrasing, and Visuwords® offers one means of vetting substitute expressions that nonexperts might find more palatable than jargon. Guidance is helpful because when behavior analysts have suggested alternatives to jargon based on “common sense” they have sometimes arrived at expressions that are as emotionally negative as some behavior analysis terms (Critchfield and Doepke 2017).

Caveats

Note in Fig. 1 that unpleasant associations with terms like extinction, punish, and discrimination are subsets of larger relational networks that, in many cases, also contain presumably pleasant or emotionally neutral associations. This highlights one major limitation of Visuwords®—it cannot indicate which associations may apply to a given listener or, when multiple associations exist, which one may predominate in a given context. Here is it important to understand how Visuwords® really operates. The WordNet® database that underpins it is, as far as can be discerned from the host website, based not on empirical behavioral research but rather on modeling guided by psycholinguistic principles (see Fellbaum 1995). At best, then, the relational networks of Visuwords® can be seen as revealing plausible associations that behavior analysts may wish to take into account when thinking about how to communicate with nonexperts.

It is important to be clear about what Visuwords® is and is not recommended for. The gut-level associations that nonexperts have with behavior analysis terms probably are relevant to what Bailey (1991) called a “marketing problem,” because it is well established that consumers tend to seek out, and follow the suggestions of, therapists with whom they feel socially comfortable (Backer et al. 1986; Barrett-Lennard 1962; Rosenzweig 1936). Communication style is an obvious mediator of that comfort, and it is also well established that general impressions about, and persuasiveness of, a sample of verbal behavior tend to correlate with an aggregate of listener positive and negative emotion responses to the words within it (e.g., Avey et al. 2011; Floh et al. 2013). Yet, to acknowledge that some behavior analysis terms are unpleasant is not to automatically imply that they should be avoided, because professional vocabulary also serves to guide actions such as pinpointing problem behaviors, implementing interventions, and so forth. Visuwords® does not indicate which ways of talking will best set the occasion for these important actions. However, when using a technical term is deemed unavoidable (no substitute term will do), Visuwords® may suggest when special explanation should be attempted to proactively diffuse unwanted associations.

Visuwords® operates entirely in English, which is unfortunate given that many behavior analysts work in other languages. Very little is known about how jargon translated into other languages may be perceived by speakers of those languages (Critchfield and Doepke 2017). It may be helpful, therefore, to have a tool like Visuwords® to supplement the limited evidence available through word-emotion databases. Fortunately, there are versions of WordNet® in other languages (http://globalwordnet.org) that interested readers may wish to explore for insights like those that Visuwords® can provide.

Conclusion and Rating

I suggest that the way to evaluate Visuwords® is not in terms of whether it could be more specific to the needs of behavior analysts in applied settings but rather in terms of whether it is better than proceeding based strictly on hunches and “common sense.” One never gets a second chance to make a first impression, and Visuwords® can provide useful insights about what behavior analysis terms may “mean” to people who are not schooled in behavior analysis. Yes, the tool is limited in several ways and its output should not be overinterpreted. This output is not a substitute for high-quality behavioral research on the field’s communication challenges. Until research-guided best practices are available, however, applied behavior analysts will find Visuwords® simple to use, intuitively understandable, and at least broadly applicable to the goal of preventing audience-insensitive verbal behavior from turning them into “Attila the Hun” in the eyes (or ears) of those who can profit from their expertise.

Product rating = 4 stars out of 5 for free access, ease of use, visually appealing output, and applicability to on an issue for which behavior analysts have generated too little discipline-specific research.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the author.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest with respect to this article.

Footnotes

References

- Avey J, Avolio BJ, Luthans F. Experimentally analyzing the impact of leader positivity on follower positivity and performance. The Leadership Quarterly. 2011;22:282–294. doi: 10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.02.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Backer TE, Liberman RP, Kuehnel TG. Dissemination and adoption of innovative psychosocial interventions. Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986;54:111–118. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.54.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JS. Marketing behavior analysis requires different talk. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24:445–448. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes Holmes D, Keane J, Barnes-Holmes Y, Smeets PM. A derived transfer of emotive functions as a means of establishing differential preferences for soft drinks. The Psychological Record. 2000;50(3):493. doi: 10.1007/BF03395367. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes Holmes D, Barnes-Holmes Y, Stewart I, Boles S. A sketch of the implicit relational assessment procedure (IRAP) and the relational elaboration and coherence (REC) model. The Psychological Record. 2010;60(3):527. doi: 10.1007/BF03395726. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett-Lennard GT. Dimensions of therapist response as causal factors in therapeutic change. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied. 1962;76:1–36. doi: 10.1037/h0093918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becirevic A, Critchfield TS, Reed DD. On the social acceptability of behavior-analytic terms: crowdsourced comparisons of lay and technical language. The Behavior Analyst. Advance online publication. doi. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s40614-016-0067-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M. Behaviorism in twenty-five words. Social Work. 1973;18:106–108. [Google Scholar]

- Cook SW, Skinner BF. Some factors influencing the distribution of associated words. The Psychological Record. 1939;3:178–184. [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield, T.S., & Doepke, K.J. (2017) Emotional overtones of behavior analysis terms in English and five other languages. Manuscript submitted for publication. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Critchfield TS, Becirevic A, Reed DD. In Skinner's early footsteps: analyzing verbal behavior in large public corpora. The Psychological Record, Advance online publication. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Critchfield, T.S., Becirevic, A., & Reed, D.D. (2017a). On the social validity of behavior analytic communication: A call for research and description of one method. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Critchfield, T.S., Doepke, K.J., Epting, L.K., Becirevic, A., Reed, D.D., Fienup, D.F., Kremsreiter, J.L., & Ecott, C.L. (2017b). Normative emotional responses to behavior analysis jargon: How not to use words to win friends and influence people. Behavior Analysis in Practice. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Doughty AH, Holloway C, Shields MC, Kennedy LE. Marketing behavior analysis requires (really) different talk: a critique of Kohn (2005) and a(nother) call to arms. Behavior and Social Issues. 2012;21:115–134. doi: 10.5210/bsi.v21i0.3914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fellbaum C. WordNet: an electronic lexical data base. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Floh A, Koller M, Zauner A. Taking a deeper look at online reviews: asymmetric effect of valence intensity on shopping behavior. Journal of Marketing Management. 2013;29:646–670. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2013.776620. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foxx RM. Suggested common north American translations of expressions in the field of operant conditioning. The Behavior Analyst. 1990;13:95–96. doi: 10.1007/BF03392525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foxx RM. Translating the covenant: the behavior analyst as ambassador and translator. The Behavior Analyst. 1996;19:147–161. doi: 10.1007/BF03393162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, D. H. (2015). Improving the public perception of behavior analysis. The Behavior Analyst, 1–7. doi:10.1007/s40614-015-0045-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jarmolowicz JP, Kahng A, Invarsson ET, Goysovich R, Heggemeyer R, Gregory MK. Effects of conversational versus technical language on treatment preference and integrity. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2008;46:190–199. doi: 10.1352/2008.46:190-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsley OR. From technical jargon to plain English for application. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1991;24:449–458. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1991.24-449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurice C. Let me hear your voice: a family's triumph over autism. New York: Random House; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA. WordNet: a lexical database for English. Communications of the ACM. 1995;38(11):39–41. doi: 10.1145/219717.219748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig S. Some implicit common factors in diverse methods of psychotherapy. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1936;6:412–415. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1936.tb05248.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner BF. The distribution of associated words. The Psychological Record. 1937;1:71–76. doi: 10.1007/BF03393192. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner, B. F. (1957). Verbal behavior. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Warriner AB, Kuperman V, Brysbaert M. Norms of valence, arousal, and dominance for 13,915 English lemmas. Behavior Research Methods. 2013;45:1–17. doi: 10.3758/s13428-012-0314-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt JC, Moe G, Gutkin TB, Andrews L. The effect of saying the same thing in different ways: the problem of language and jargon in school-based consultation. Journal of School Psychology. 1984;22:361–367. doi: 10.1016/0022-4405(84)90023-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]