Abstract

In higher education, instruction that incorporates effective performance skills training is vital to equipping pre-service teachers with the tools they will use to educate children. This study evaluated the effects of behavioral skills training (BST) on performance of evidence-based practices by undergraduate pre-service special education teachers. A pre–post design was used to evaluate performance during role-play. BST sessions produced higher levels of correct performance than baseline measures across all seven participants. We discuss limitations of these results with suggestions for future research, along with recommendations for incorporating BST into university settings.

Keywords: Evidence-based practice, Teacher training, College teaching, Behavioral skills training

Evidence-based practices (EBPs) are instructional techniques that have been shown through reliable, trustworthy research to improve students’ learning and behavior (Cook, Tankersley, & Jarjusola-Webb, 2008). Special education teachers’ accurate implementation of EBPs can significantly improve academic and social outcomes for students with disabilities (Vaughn & Dammann, 2001). Teachers tend to rely on personal preferences and experiences rather than on empirical support when selecting instructional practices (Cook, Tankersley, & Landrum, 2013). In a survey of 174 special education teachers and 333 school psychologists, participants reported using ineffective practices (i.e., practices lacking empirical support) as frequently as those with empirical support (Burns & Ysseldyke, 2009).

Higher-education faculty may be wise to adopt EBPs of their own for use in university settings. Unfortunately, research on evidence-based teaching in post-secondary institutions is less common than in K–12 settings (Groccia & Buskist, 2011). Research is needed on how to most effectively and efficiently teach course material, particularly performance skills, such as EBPs, that are taught with the ultimate goal of on-the-job usage. The typical university lecture may enhance students’ verbal skills, such as their ability to answer questions, but it is unlikely to equip them with performance skills because it does not require their demonstration of target skills (see Parsons, Rollyson, & Reid, 2012). Parsons et al. (2012) suggest different evidence-based procedures are required to train performance skills than verbal skills. Teacher educators must integrate performance skills training procedures into their college teaching methods if their students (i.e., pre-service teachers) are to be equipped with EBPs for use on the job.

Behavioral skills training (BST) is an empirically established method for helping people acquire skills, and it involves four components: (a) instructions, (b) modeling, (c) role-play, and (d) feedback (Parsons et al., 2012). BST has been used to teach a variety of skills to caregivers, staff, and teachers, including the implementation of EBPs such as the picture exchange communication system (Homlitas, Rosales, & Candel, 2014), behavior management strategies (Sawyer, Crosland, Miltenberger, & Rone, 2015), and functional analyses (Iwata et al., 2000). The literature supporting the efficacy of using BST to teach performance skills to adult learners suggests it may be an effective procedure for use in university-based teacher preparation courses that have traditionally relied on the transference of skills via lecture.

The purpose of the present study was to extend the literature on the use of BST with adult learners by examining its effects on undergraduate pre-service special education teachers’ performance of EBPs via role-play scenarios.

Method

Participants, Setting, and Materials

Seven female undergraduate participants ranging in age from 19 to 23 years old were recruited from a special education program at a large American university. Three participants were planning to apply to the program in the subsequent autumn semester, two had already been admitted, and two were completing their final semester in the program at the time of the study. All sessions occurred on campus. Lectures were conducted in a conference room with a screen projector, table, and chairs. BST sessions were conducted in a separate room with tables and chairs.

EBP Checklists

Seven EBPs were selected from the website of the National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorder (NPDC; http://autismpdc.fpg.unc.edu/evidence-based-practices). EBPs included constant time delay, differential reinforcement of other behavior, discrete trial teaching, functional communication training, naturalistic intervention, least-to-most prompting, and response interruption/redirection. The researchers (i.e., six graduate students and one faculty) modified the implementation checklists available on the website to include discrete, measurable behaviors that would be observed during classroom implementation. An eighth EBP, multiple stimulus without replacement preference assessment, was also selected. The NPDC includes “using learner preferences” as a strategy under the EBP “Antecedent-Based Interventions,” and the ability to conduct preference assessments is a vital skill related to implementing EBPs (Alexander, Ayres, & Smith, 2015); therefore, the researchers included multiple stimulus without replacement among the targeted skills. Each EBP was assigned to a researcher who independently adapted the checklist. Once created, the researchers reviewed all of the checklists, reaching consensus on whether the critical features that were listed on the website were represented.

Scenarios

Two contrived scenarios were developed for each EBP; one for the pre- and post-test role-play assessments and one for the BST session role-play practice. Each scenario included hypothetical information regarding student characteristics and classroom setting, an academic or social skill deficit, and an EBP to use to address the issue. Any materials that were necessary to implement the EBP for a given scenario were available to participants.

Microsoft PowerPoint presentations were created for each EBP including six slides (i.e., a title slide; slides with the EBP description, when to use it, how to prepare to use it, and the EBP checklist; and one slide to solicit participant questions). A projector was used to present the slides on a large screen, and participants were given printed copies of the slides. Participants were provided paper and pens for note-taking and were permitted access to their notes and copies of the slides during all sessions. In addition, participants were provided the practice role-play scenarios in writing.

Dependent Variables and Measurement

The dependent variable was the performance during pre- and post-test role-play assessments. Performance was scored using the EBP checklists. For each assessment, a researcher read aloud the scenario, and then asked the participant to role-play implementing the EBP with the researcher acting as the student in the scenario. Data collectors scored a “+” for each step the participant performed correctly and a “−” for each step performed incorrectly. The number of steps performed correctly was divided by the total number of steps and multiplied by 100 to yield a percentage of steps performed correctly. Session role-play assessments were conducted at the conclusion of every session. Pre-test and post-test role-play assessments were conducted prior to and at the conclusion of experimental conditions, respectively.

Experimental Design

A pre- and post-test design was used to compare participant performance before BST and following BST exposure.

Experimental Conditions

One EBP was targeted per session with three or four participants (group A and group B), and each session began with a researcher presenting the PowerPoint slides and a 5–10-min lecture. All student questions were answered during the lecture, but no modeling, role-play, or feedback was provided. The lecture was terminated once participants indicated they had no further questions. In their groups following the lecture, participants simultaneously engaged BST.

BST Sessions

First, a researcher reviewed the EBP checklist and modeled implementing the EBP with another researcher acting as the student in the scenario, who displayed both typical and atypical behaviors. Next, participants role-played implementing the EBP in dyads or triads, with participants taking turns acting as the student, while the researchers observed and provided feedback. The researchers answered all participant questions during the BST session and provided further modeling as needed. The role-plays continued until all participants had received praise and corrective feedback from a researcher and reported that they were ready to “check-out.” During the checkout, each participant implemented the EBP with a researcher acting as the student in the scenario. All participants were required to reach a mastery criterion of 100% correct performance during the checkout, and if a participant failed to do so, she was instructed to continue practicing with her group until she was ready to try again. Once all participants reached the mastery criterion, the BST session was terminated. BST sessions lasted approximately 20 min.

Interobserver Agreement and Procedural Fidelity

Prior to conducting the pre-tests, data collection training scenarios were used to ensure reliability in scoring EBP implementation across researchers. Two researchers role-played the scenario, and the others scored the EBP checklist. An agreement was defined as both observers scoring an item identically. Percentage agreement for each EBP was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the number of disagreements plus agreements and converting to a percentage. Once all of the researchers reached 100% agreement with the first author for each EBP, data collection began. Interobserver agreement was assessed for 100% of pre- and post-tests and 88% of session assessments. Mean agreement was 98% across pre- and post-tests (range, 40 to 100%) and 97.9% across session assessments (range, 94 to 100%).

In order for participants to have the opportunity to implement the various steps of an EBP, the “student” in the role-play scenario was required to engage in particular behaviors. Using student behavior checklists, fidelity was assessed during 72% of role-play assessments. Student behavior fidelity was 98% across assessments (range, 92 to 100%). Mean procedural fidelity assessed for 72% of sessions was 99% (range, 96 to 100%).

Results

Pre-Tests and Post-Tests

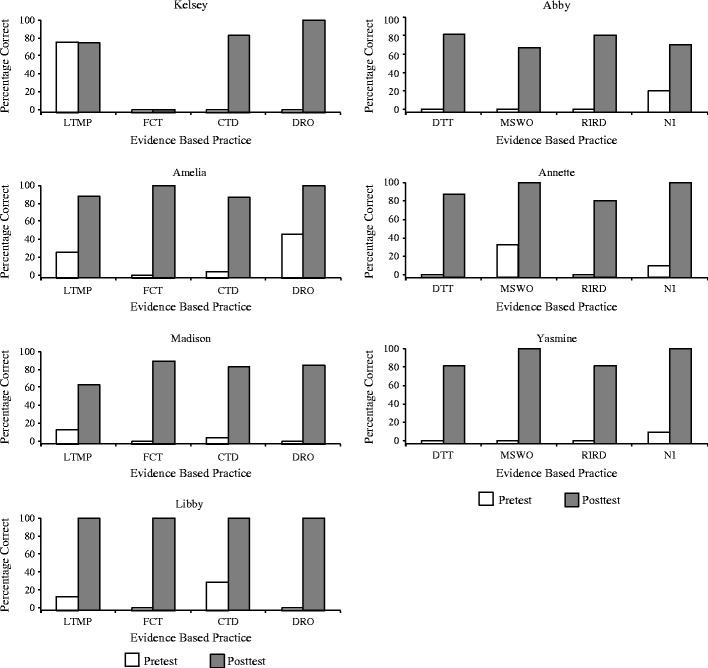

Figure 1 presents individual pre-test and post-test data for all seven participants. Across participants, scores on pre-test and post-test role-plays averaged 10 and 85%, respectively. It should be noted that no change was observed in one participant’s (Kelsey) performance following BST on functional communication training from pre-test to post-test assessment.

Fig. 1.

Percentage of correct EBP performance on pre-test and post-test following BST. LTMP least to most prompting, FCT functional communication training, CTD constant time delay, DRO differential reinforcement of other behavior, NI naturalistic intervention, MSWO multiple stimulus without replacement preference assessment

Discussion

The current study extends the literature on the use of BST in higher education by evaluating effects on pre-service teachers’ performance of EBPs. Unlike assessments of knowledge skills (e.g., answering questions on paper-pencil tests) typically conducted in university settings, this study evaluated performance skills via participant demonstration during role-play assessments. Similar to previous findings, BST resulted in high levels of accuracy across targeted skills (Sawyer et al., 2015). The results of this study suggest that systematic didactic instruction may be more effective in training undergraduates how to implement performance skills, such as EBPs, when combined with BST than when combined with traditional studying behaviors. BST led to higher levels of correct performance across all EBPs.

Findings of the current investigation should be considered in light of several limitations, and scholars interested in furthering this line of research are likely to identify modifications in addition to the suggested ones that follow. Due to time constraints imposed by conducting this project within the course of a semester, the primary dependent variable, EBP performance during pre- and post-test role-play assessments, was measured only once for each EBP and no long-term skill maintenance data were collected. This limits conclusions regarding the durability of trained skills. The current experimental design did not enable optimal control of participants’ extra-experimental learning history, maturation, or practice effects. Additionally, performance was assessed via role-play of hypothetical scenarios and only a small sample of undergraduates participated, potentially limiting the external validity of the results and conclusions regarding the extent to which teachers would generalize taught skills to actual students in classroom settings. Future research should evaluate the scalability of these procedures within larger college teaching contexts, ensure repeated measurement conducted over time, examine these procedures with a larger participant size or through a multiple baseline design, and include generalization measures of teachers’ classroom implementation of EBPs with actual students.

Although the small group of participants in the present investigation may raise questions about whether these procedures can be effectively utilized during regular large group instruction in university settings, the authors hold that doing so is not only feasible; it is the obligation of responsible higher-education faculty. Although lectures alone require less response effort on the part of both student and instructor, instruction that does not produce the necessary outcome is not cost-effective. The onus of graduating career-ready professionals includes equipping students with more than knowledge skills; career-ready individuals possess the performance skills necessary to successfully fulfill their job requirements. In order to equip undergraduates with those skills, higher education faculty must integrate effective training procedures into their practice. To facilitate the use of BST in college courses, instructors could introduce new skills via didactic instruction then model implementation via role-plays or videotaped observations. Students could then practice implementing taught skills in pairs or triads while receiving feedback from their peers and the instructor, as demonstrated in the present study.

How to Incorporate BST into the University Classrooms

Incorporating BST into college classrooms might seem like a daunting task, especially when classes are comprised of 20 or more students. To mitigate the issue of providing opportunities to role-play paired with immediate, valuable feedback, instructors may consider the following strategies. First, train a handful of students in the classroom as expert trainers to implement BST within a pyramidal training model. Not only will the selected expert-students gain knowledge from the course content, they will also have a training skill that will support them when working with classroom practitioners in the field. These trained students can act as guides when engaging in role-play and can provide feedback to the students in the class. Second, consider having students videotape themselves working with students or role-playing with peers outside of class. Then, when together in class, the other students in the class can practice providing feedback. This strategy can be very powerful, presenting at least three learning opportunities from which students may benefit. First, students must plan and prepare in advance for the delivery of instruction or use of the EBP; next, they gain practice in actually using the EBP (role-play or live instruction with children); and finally, they receive feedback and reflect on their practice with a classroom of peers to support them.

Alternatively, students can videotape themselves engaging in a learned practice and upload those videos to a secure website where the instructor can provide feedback with a rubric and specific time stamps where students can improve. Although this option would reduce time in class dedicated to feedback, it would be rather time-consuming if the instructor was evaluating dozens of videos alone. One way to make this option more efficient would be to assign previously trained expert-students to also provide feedback for several students. The instructor could probe the videos to ensure accurate feedback is being delivered. These options all require more planning by the instructor and allotment of class time for role-play and feedback. This might be quite an adjustment for some instructors given the prevalence of didactic instruction in the form of lecturing in university-based teaching environments. But, we know that didactic instruction alone is likely insufficient in training performance skills.

Notwithstanding its limitations, this study contributes to the growing body of literature on evidence-based college teaching practices. Lecture combined with BST was brief, rated acceptable by participants, and produced sizable gains on the session role-play assessments. Future research and practice in higher education should continue to assess efficient and effective methods of college teaching that produce desirable behavior change.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

This research was conducted at The Ohio State University, where all authors were affiliated at the time of the study.

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

Mary Sawyer declares that she has no conflict of interest. Natalie Andzik declares that she has no conflict of interest. Michael Kranak declares that he has no conflict of interest. Carolyn Willke declares that she has no conflict of interest. Emily Curiel declares that she has no conflict of interest. Lauren Hensley declares that she has no conflict of interest. Nancy Neef declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

• Pre-service special education teachers must be trained to use a specialized set of performance skills known as evidence-based practices that have been shown to improve academic and social outcomes for students with disabilities.

• Although legislation has mandated the use of EBPs, they are infrequently implemented in classrooms.

• If teachers are to use EBPs in their classrooms, teacher educators must be competent in training them to do so.

• When using EBPs in the classroom with fidelity, students with disabilities demonstrate positive outcomes.

References

- Alexander JL, Ayres KM, Smith KA. Training teachers in evidence-based practice for individuals with autism spectrum disorder: a review of the literature. Teacher Education and Special Education. 2015;38:13–27. doi: 10.1177/0888406414544551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burns MK, Ysseldyke JE. Reported prevalence of evidence-based instructional practices in special education. The Journal of Special Education. 2009;43:3–11. doi: 10.1177/0022466908315563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BG, Tankersley M, Jarjusola-Webb S. Evidence-based special education and professional wisdom: putting it all together. Intervention in School and Clinic. 2008;44:105–111. doi: 10.1177/1053451208321566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BG, Tankersley M, Landrum TJ. Evidence-based practices in learning and behavioral disabilities: the search for effective instruction. Advances in Learning and Behavioral Disabilities. 2013;26:1–19. doi: 10.1108/S0735-004X(2013)0000026003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Groccia JE, Buskist W. Need for evidence based teaching. In: Buskit W, Groccia JE, editors. Evidence based teaching. Hoboken: Wiley Periodicals, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Homlitas C, Rosales R, Candel L. A further evaluation of behavioral skills training for implementation of the picture exchange communication system. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2014;47:198–203. doi: 10.1002/jaba.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwata BA, Wallace MD, Kahng S, Lindberg JS, Roscoe EM, Conners J, et al. Skill acquisition in the implementation of functional analysis methodology. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2000;33:181–194. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2000.33-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons MB, Rollyson JH, Reid DH. Evidence-based staff training: a guide for practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2012;5:2–11. doi: 10.1007/BF03391819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer M, Crosland K, Miltenberger R, Rone A. Using behavioral skills training to promote the generalization of parenting skills to problematic routines. Child and Family Behavior Therapy. 2015;37(4):261–284. doi: 10.1080/07317107.2015.1071971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn S, Dammann JE. Science and sanity in special education. Behavioral Disorders. 2001;27:21–29. [Google Scholar]