Abstract

Inhalation anesthetics isoflurane may increase the risk of neurotoxicity and cognitive deficiency at postnatal and childhood. Chikusetsu saponin IVa (chIV) is a plant extract compound, which could possessed extensive pharmacological actions of central nervous system, cardia-cerebrovascular system, immunologic system and treatment and prevention of tumor. In our study, we investigated the neuroprotective effect of chIV on isoflurane-induced hippocampal neurotoxicity and cognitive function impairment in neonatal rats. ChIV or saline intraperitoneal injected into seven-day old rats 30 min prior to isoflurane exposure. We found that, anesthesia with 1.8% isoflurane for 6 h significantly decreased the expression of SIRT1 in hippocampus. ChIV increased SIRT1, p-ERK1/2, PSD95 level in hippocampus, decreased hippocampal neuron apoptosis and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release after isoflurane exposure. Furthermore, chIV improved adolescent spatial memory of rats after their neonatal exposure to isoflurane by Morris Water Maze (MWM) test. In addition, SIRT1 inhibitor sirtinol decreased the expression of SIRT1 and its downstream of p-ERK1/2. Taken together, our date suggested that chIV could ameliorate isoflurane-induced neurotoxicity and cognitive impairment. The neuroprotective effect of chIV might be associated with up-regulation of SIRT1/ERK1/2. Moreover, chIV appeared to be a potential therapeutic target for isoflurane induced developmental neurotoxicity as well as subsequent cognitive impairment.

Keywords: Chikusetsu saponin IVa, isoflurane, hippocampus, SIRT1, neurotoxicity

Introduction

As a non-pungency inhaled agent with less respiratory irritation, isoflurane has been widely used in pediatric operations. Some researches reported that exposured to isoflurane at postnatal and early childhood stage might increase the risk of impairment in learning and memory [1-3]. Numbers of studies had demonstrated that isoflurane could cause neuroapoptotic, synaptogenesis deficiency and learning and memory dysfunction in developmental of both rodents and non-human primates [4-8]. However, the exactly mechanisms underlying isoflurane-induced neurotoxicity and cognitive deficiency were not clearly understood.

SIRT1, an NAD+ dependent class III histone deacetylase, was an important regulator of cell survival and multiple neurodegenerative disorders [9-11]. A growing number of evidence showed that pharmacological activation or upregulation of SIRT1 expression exhibited neuroprotective effects in several models of neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson and Huntington diseases as well as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [12-15]. At early stages of development, overexpression SIRT1 was sufficient to regulate dendritic morphogenesis and enhance dendritic arborization in hippocampal neurons [16]. It also involved in protective of acute neurotoxic stress [17]. In addition, SIRT1 deacetylase also promotes memory and normal cognitive function [18]. The above evidence suggested that SIRT1 possibly involve in the role of neuroprotective and contributed to cognitive function.

Chikusetsu saponin IVa (chIV) is a sort of plant extract compound from Panacis japonica and it is a common traditional herbal medicine in Tujia and the Hmong people of China [19]. Recent years, chIV was reported extensive pharmacological actions of central nervous system, cardia-cerebrovascular system, immunologic system and treatment and prevention of tumour [20]. ChIV had been reported to reverse Ca2+ overload and oxidative stress in cardiomyocytes of mice with diabetic cardiac disorders [21] and provide a protective effect on myocardial infarction [22]. In addition, chIV was able to decrease mitochondrial membrane potential and provide a neuroprotective effect in Parkinson’s disease (PD) [23]. It also could attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury [24] and against oxidative stress [20]. Therefore, chIV had a remarkable effect on anti-apoptosis, inflammation, thrombotic and reduced oxidative stress [20-25]. In present study, we aimed to investigate chIV neuroprotective effect on isoflurane-induced neurotoxicity and cognitive deficiency as well as the underlying molecular mechanism.

Materials and methods

Animals

Pregnant Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were from the Laboratory Animal Centre of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Wuhan, China). Rats kept in standard laboratory housing under a 12-h light/dark cycle, with freely eating and drinking. All experimental protocols and animal handling procedures were performed in accordance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 80-23, revised in 1996) and the experimental animal committee of Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology approved experimental protocols.

Experimental groups and drug treatment

At seven day after birth, pup rats were randomly divided into four groups: control group (con): intraperitoneal injected saline 100 μl with control gas exposure for 6 h; isoflurane group (iso): intraperitoneal injected saline 100 μl with 1.8% isoflurane exposure for 6 h; chIV group (chIV): intraperitoneal injected chIV 30 mg/kg (100 μl) with control gas exposure for 6 h; chIV+isoflurane group (chIV+iso): intraperitoneal injected chIV 30 mg/kg (100 μl) with 1.8% isoflurane exposure for 6 h. Saline and chIV intraperitoneal injected 30 min prior to control gas or isoflurane exposure.

Isoflurane exposure

Iso group and chIV+iso group rats were received isoflurane exposure at seven day after birth. The chamber (20×20×10 cm) was kept in a homoeothermic incubator to maintain 37°C.Rats received 1.8% isoflurane flushed with 60% oxygen (balanced with air) or the control gas for 6 h in the chamber. An infrared probe (OhmedaS/5 Compact, Datex-Ohmeda, Louisville, CO, USA) detected the isoflurane, oxygen and carbon dioxide concentration during anesthesia. After isoflurane exposure, a sample of 100 μl blood was collected to determine the pH, arterial oxygen, carbon dioxide tensions, base excess, and blood glucose with a blood gas analyzer (Kent Scientific Corp., Torrington, CT, USA).

Primary hippocampal neuron culture and treatment

0-24 h newborn SD rats were from the Laboratory Animal Centre of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology (Wuhan, China). Primary hippocampal neuron culture was according to provirus described [26]. In brief, hippocampus were digested with 0.125% trypsin for 15 min at 37°C and cells were seeded into 12-well plates with DMEM/F12 medium (Gibco, Waltham, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Waltham, USA). The density of primary hippocampal neuron in 12-well plates was 4×104 cells/well. Medium was replaced by Neurobasal A (Gibco, USA) and 2% B27 (Gibco, USA) after 4 h. Hippocampal neurons were stained with Neun (neuronal biomarker) to identified by immunofluorescent and over 95% cells were hippocampal neurons. At 7 d of culture, 25 μg/ml chIV or 15 μmol sirtinol added into medium 6 h prior to isoflurane exposure or control gas. Experiment repeated at least three times.

Morris water maze (MWM) test

MWM test was performed as we describe provirus [27]. At P22 (22 d after birth), rats were separated from mother rats and started training at P31 (31 d after birth). The training contained 3 trials (120 s maximum; interval 20 min) every day and last for 5 day in a row. At the fifth day, probe trial was preformed after 1 h following the training. Path length, duration of time spent in each quadrant, time spend searching, latency and platform crossing were recorded and analyzed.

Western blot analysis

Western blotting was performed as protocols published in our previous experiments. In brief, samples were homogenized with RIPA buffer (150 mM sodium chloride, Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0) at 4°C for 30 min. Then removed sediment following sample were centrifuged for 15 min at 4°C. BCA protein assay kit (Boster, Wuhan, China) was used to determine the protein levels in supernatant. The samples were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). Bands were blocked with 5% BSA in TBST (0.1% Tween 20 in Tris-buffered saline) for 1 h. Relative primary antibodies were incubated at 4°C overnight: rabbit synapsin-I (1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), rabbit Erk1/2, phosphor-Erk1/2, PSD-95 (1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), mouse SIRT1 (1:500, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), rabbit Bax, Bcl-2 (1:800, Abclonal, Wuhan, China). Then bands were washed with TBST and incubated second antibody for 2 h at room temperature: goat anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase or goat anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase (1:5000, Qidongzi, Wuhan, China). Finally, these bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with the ChemiDoc-XRS chemilumi-nescence imaging system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Experiments were repeated at least for three times.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay

LDH assay was used to determine the cytotoxicity after isoflurane exposure. Samples were homogenated with saline, then supernatant was collected following centrifuged at 4°C. The LDH concentration was measured by LDH assay kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 20 μl supernatant from different group was reacted with nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide and pyruvate at 37°C for 15 min in 96-well cell culture plate. 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine was added to each well and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. The reaction was stopped by NaOH (0.4 mol/L). Absorbance was used to measure LDH release of different group at 450 nm.

Cell viability assays

Viability of primary hippocampal neuron were detected by cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8, Boster, Wuhan, China) assay. Primary hippocampal neuron were seeded with 1×104 cells/well in 96-well plates. After different treatment, 10 μl CCK-8 solution was added to each well and wells were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Absorbance was used to measure optical density of each well at 450 nm.

TUNEL assays

TUNEL staining was performed according to provirus manufacturer (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) [28]. Hippocampal tissue sections (5 μm thickness) were used for TUNEL immunohistochemically staining. TUNEL stained positive cells were counted as score of apoptotic cells. The staining intensity was evaluated by Image-Pro plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA). Experiment repeated for three times.

Statistical analysis

The data were presented as mean ± SEM and all the data were analyzed with SPSS software 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Armonk, New York, USA). Two-way ANOVA (treatment and time) was used to analyze escape path length and escape latency in the MWM test. Other data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by the Dunnett’s test. p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Physiological parameters

The parameters of pH, PaCO2, PaO2, glucose and SaO2 were in the normal range. There were no difference among four experiment groups (p>0.05, Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of isoflurane exposure on physiological parameters of arterial blood gas analysis in neonatal rats

| Con | Iso | ChIV+iso | ChIV | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PH | 7.32±0.06 | 7.33±0.03 | 7.34±0.06 | 7.33±0.05 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 37.7±3.9 | 40.5±3.3 | 39.2±4.4 | 37.1±3.0 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 104±11 | 106±9 | 108±12 | 103±9 |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 4.3±0.9 | 3.9±0.4 | 4.2±0.6 | 4.5±0.8 |

| SaO2 (%) | 99±1.2 | 98±0.8 | 98±1.1 | 99±0.6 |

The pH, PaCO2, PaO2, glucose and SaO2 levels did not differ significantly among the four groups. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 5 per group). PaO2, arterial oxygen tension; PaCO2, arterial carbon dioxide tension; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation.

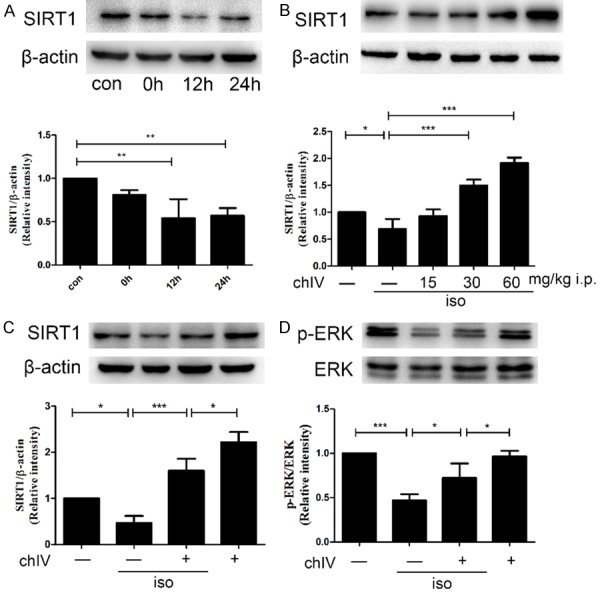

ChIV ameliorated isoflurane-induced suppression of SIRT1

To investigate the effect of isoflurane on SIRT1 expression in neonatal hippocampus, we detected SIRT1 expression after isoflurane exposure by western blot. As shown in Figure 1A, SIRT1 decreased approximately as a time-dependent manner (p<0.01) after isoflurane exposure and reached to the lowest level at 12 h after isoflurane exposure. Therefore, we chose 12 h after isoflurane exposure in our following experiment.

Figure 1.

Isoflurane (1.8%, 6 h) suppressed SIRT1 expression in P7 rats and ChIV could ameliorate isoflurane-induced suppression of SIRT1. A. Hippocampal SIRT1 expression decreased at 0, 12, 24 h after isoflurane exposure as a time-dependent manner. B. Administration of chIV (30 and 60 mg/kg, i.p.) significantly attenuated isoflurane-induced decrease in hippocampal protein expressions of SIRT1 in neonatal rats. C. The effects of isoflurane (1.8%, 6 h) and chIV (30 mg/kg, i.p.) on hippocampal protein expressions of SIRT1 in neonatal rats. D. The effects of isoflurane (1.8%, 6 h) and chIV (30 mg/kg, i.p.) on hippocampal protein expressions of p-ERK1/2 in neonatal rats were detected by Western blot analysis. Application of chIV significantly attenuated isoflurane-induced decrease in hippocampal protein expressions of p-ERK1/2 in neonatal rats. con: control group; 0 h: 0 h after 1.8% isoflurane exposure; 12 h: 12 h after 1.8% isoflurane exposure; 24 h: 24 h after 1.8% isoflurane exposure. Data were presented as mean ± SEM (n = 7 per group). *denotes p<0.05, **denotes p<0.01, ***denotes p<0.001 when comparing the two groups under each end of the capped line.

ChIV was reported to upregulate high glucose induced SIRT1 decrease and attenuate myocardium apoptosis in myocardium of mouse [21]. Thus, we explored the effect of chIV on isoflurane-induced suppression of hippocampal protein SIRT1 level. We chose three different concentrate of chIV 15 mg/kg, 30 mg/kg and 60 mg/kg in our study. Our data demonstrated that 30 mg/kg, 60 mg/kg chIV effectively increased SIRT1 expression at 12 h after isoflurane exposure (Figure 1B, p<0.001 or p<0.05). Based on our results, we selected a dose of 30 mg/kg in our following studies.

Then, we tested the effect of isoflurane or 30 mg/kg chIV on SIRT1 and p-ERK1/2 expression in hippocampal of neonatal rats by Western blot. The results shown that isoflurane suppressed SIRT1 and p-ERK1/2 expression, whereas this suppression could reverse by chIV 30 mg/kg i.p. pretreatment (Figure 1C and 1D, p<0.05 or p<0.001).

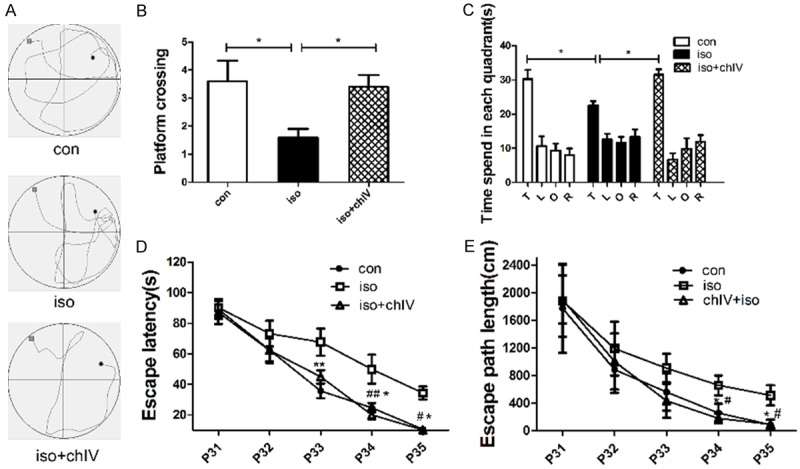

ChIV pretreatment improved spatial memory impairment after isoflurane exposure

To determine the behavioral effects of isoflurane and chIV, MWM was used to evaluate spatial learning and memory at 24 d (P31) after isoflurane exposure. Isoflurane exposure impaired the spatial memory as revealed by less time in the target quarter (Figure 2C, p<0.05), longer escape latency (Figure 2D, p<0.05 or p<0.01) and increased travel distance (Figure 2E, p<0.05) compared with con group. However, the impairment of spatial memory induced by isoflurane could reverse by chIV pretreatment. ChIV pretreatment rats displayed shorter travel distance (Figure 2E, p<0.05), escape latency decreased (Figure 2D, p<0.05 or p<0.01) and spend more time in the target quarter (Figure 2C, p<0.05) compared with iso group.

Figure 2.

Spatial memory deficits induced by neonatal exposure to isoflurane were alleviated by the treatment of chIV (30 mg/kg, i.p.). A. Representative swim paths obtained during trial 3 (session 4) from rats in the three experimental group. B. The platform crossing times during probe trial of MWM test. Data were presented as mean ± SEM (n = 10 per group). *denotes p<0.05 when comparing the two groups under each end of the capped line. C. The analysis of the time spent in each quadrant during the probe test of MWM. Data were presented as mean ± SEM (n = 10 per group). *denotes p<0.05 when comparing the two groups under each end of the capped line. D. Escape latency in the Morris water maze plotted against the training days. Repeated measures ANOVA followed by a post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison test (n = 10 per group): *denotes p<0.05, **denotes p<0.01 con vs iso. #denotes p<0.05, ##denotes p<0.01 iso vs iso+chIV. E. Escape path length in MWM plotted against the training days. Repeated measures ANOVA followed by a post hoc Bonferroni multiple comparison test (n = 10 per group): *denotes p<0.05 con vs iso. #denotes p<0.05 iso vs iso+chIV.

In the probe trial, isoflurane anesthesia decrease the platform crossing compared with con group (Figure 2A, p<0.05). Pretreatment with chIV could improve the spatial memory deficiency in young rats as indicated by increase platform crossings compared to isoflurane treatment (Figure 2A, p<0.05). Our results demonstrated that chIV pretreatment improved adolescent spatial memory of rats after their neonatal exposure to isoflurane.

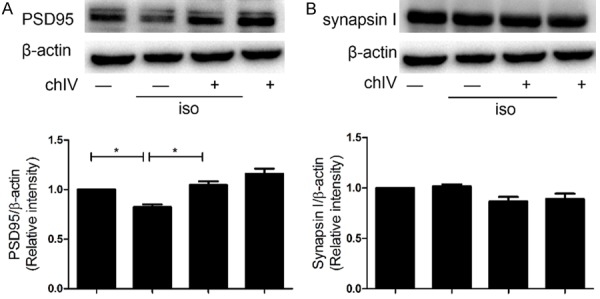

ChIV restored isoflurane-induced PSD95 level reduction in hippocampus of neonatal rats

It had been reported that isoflurane induced cognitive dysfunction in neonatal rats, which was associated with deficiency of synaptic relative protein synthesis. Therefore, we detected whether chIV could reverse isoflurane-induced synaptogenesis obstacle in neonatal rats. We found that isoflurane decreased PSD 95 expression in hippocampus compared to the saline-treated rats (Figure 3A, p<0.05), whereas the expression of synapsin I was not statistically significant (Figure 3B, p>0.05). In addition, 15 mg/kg chIV i.p. effectively improved PSD 95 expression in hippocampus of neonatal after isoflurane exposure (Figure 3A, p<0.05) but did not alter synapsin I expression in hippocampal of neonatal rats (Figure 3B, p>0.05).

Figure 3.

ChIV reversed isoflurane-induced decrease in hippocampal PSD-95 expressions in neonatal rats. The effects of isoflurane (1.8%, 6 h) and chIV (30 mg/kg, i.p.) on hippocampal protein expressions of PSD-95 (A), SNAP-25 (B) in neonatal rats were detected by Western blot analysis. (A) Isoflurane exposure induced a significant decrease in hippocampal protein expressions of PSD-95, whereas the decrease was reversed by the application of chIV. (B) Isoflurane exposure or combined treatment of chIV didn’t alter hippocampal protein levels of synapsin I in neonatal rats. Data were presented as mean ± SEM (n = 7 per group). *denotes p<0.05 when comparing the two groups under each end of the capped line.

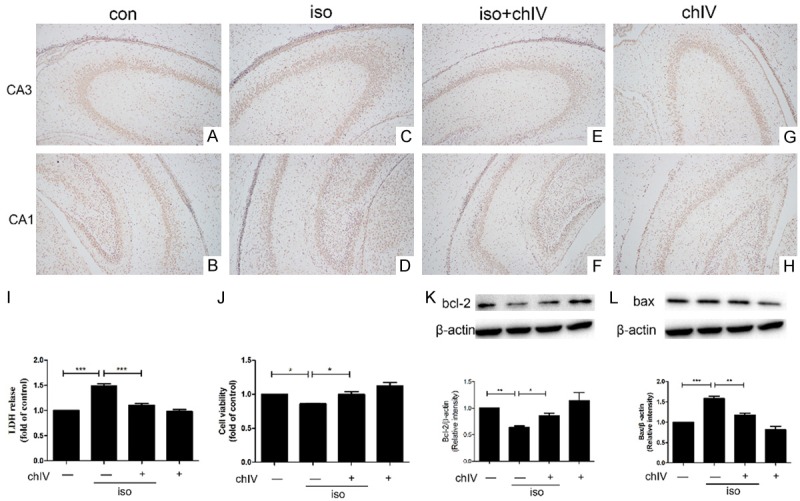

ChIV mitigated isoflurane-induced apoptosis in hippocampus of neonatal rats

Previous studies demonstrated that isoflurane exposure during neonatal caused widespread neuroapoptosis in hippocampus and amplified impairment in long-term cognitive function in juvenile [7]. Therefore, we test whether chIV could confer neuroprotective effect in hippocampal of neonatal after isoflurane exposure by TUNEL assays, LDH release assays, cell viability assay and Western blot. Isoflurane increased amount of TUNEL positive cell in both CA1 and CA3 region (Figure 4A-D) and LDH release (Figure 4I, p<0.001) in hippocampal tissue compared to saline-treat group. The primary hippocampal neuron viability reduced after isoflurane exposure with CCK8 assays (Figure 4J, p<0.05). In addition, we detected pro-apoptotic factor Bax and anti-apoptotic factor Bcl-2 in hippocampus by western blot after isoflurane-treated. As shown in Figure 4K and 4L, isoflurane increased Bax protein expression while decreased Bcl-2 protein expression (p<0.05 or p<0.001), which was consistent with our provirus results. However, isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis both in vivo and in vitro was mitigated after chIV pretreatment. Consistent with our hypothesis, chIV pretreatment reduced amount of TUNEL positive hippocampal neuron both CA1 and CA3 region (Figure 5E-H) and decreased LDH release (Figure 4I, p<0.001) after isoflurane anesthesia. Furthermore, chIV also increased cell viability after isoflurane anesthesia (Figure 4J, p<0.05) and upregulated protein Bax and Bcl-2 expression after isoflurane exposure (Figure 4K and 4L, p<0.05 or p<0.01).

Figure 4.

ChIV mitigated isoflurane-induced apoptosis in hippocampus of neonatal rats and primary hippocampal neruon. A-H. The treatment of chIV (30 mg/kg, i.p.) significantly reduced isoflurane (1.8%, 6 h)-induced increase of TUNEL positive cell in hippocampus CA1 and CA3 region of neonatal rats. I. Pretreatment with chIV (30 mg/kg, i.p.) significantly reduced isoflurane (1.8%, 6 h)-induced up-regulation of LDH release in the hippocampus of neonatal rats. J. Application of chIV (25 μg/ml) in primary hippocampal neuron promoted cell viability after isoflurane anesthesia. K. Administration of chIV (30 mg/kg, i.p.) significantly attenuated isoflurane (1.8%, 4 h)-induced down-regulation of Bcl-2 in the hippocampus of neonatal rats. L. Application of chIV (30 mg/kg, i.p.) significantly reduced isoflurane (1.8%, 6 h)-induced enhancement of Bax in the hippocampus of neonatal rats. Data were presented as mean ± SEM (n = 7 per group). *denotes p<0.05, **denotes p<0.01, ***denotes p<0.001 when comparing the two groups under each end of the capped line.

Figure 5.

ChIV-induced neuroprotective effect after isoflurane anesthesia (1.8%, 6 h) was mediated by SIRT1/ERK1/2 pathway. A. Different concentration of chIV (12.5, 25, 50 μg/ml) had no significant effect on primary hippocampal neuron viability. B. A graph representative of Western blot analysis of nuclear SIRT1, p-ERK1/2 expressions in primary hippocampal neuron. C. The statistical analysis showed that chIV (25 μg/ml) induced upregulation of SIRT1 was counteracted by sirtinol in isoflurane anesthesia. D. The statistical analysis showed that chIV (25 μg/ml)-induced upregulation of p-ERK1/2 was counteracted by sirtinol. E. Sirtinol counteracted chIV (25 μg/ml)-induced increase of cell viability in primary hippocampal neuron. F. Sirtinol counteracted chIV (25 μg/ml)-induced decrease of LDH release. Data were presented as mean ± SEM (n = 7 per group). *denotes p<0.05, **denotes p<0.01, ***denotes p<0.001 when comparing the two groups under each end of the capped line.

ChIV-induced neuroprotective effect after isoflurane anesthesia was mediated by SIRT1/ERK1/2 pathway

According to our results, chIV upregulated SIRT1, p-ERK1/2 level and provided neuroprotective effects on neonatal hippocampal tissue. However, whether chIV pretreatment prevented primary hippocampal neuron apoptosis was unknown. We detected 12.5 μg/ml, 25 μg/ml and 50 μg/ml chIV in vitro to ensure these doses were safe to cells by CCK8 assays (Figure 5A, p>0.05). Then we chose dose of 25 μg/ml in our following experiment. Consistent with our provirus results in vivo, isoflurane suppressed SIRT1, p-ERK1/2 level (Figure 5C and 5D, p<0.05 or p<0.01) whereas chIV pretreatment attenuated the suppression of SIRT1 and p-ERK1/2 expression induced by isoflurane (Figure 5C and 5D, p<0.05 or p<0.01). These finding demonstrated that chIV up-regulated SIRT1, p-ERK1/2 level both in vivo and in vitro after isoflurane anesthesia.

Next, we further investigated the role of SIRT1 in chIV-induced neuroprotective effect after isoflurane exposure. We applied sirtinol, an inhibitor of SIRT1, in primary hippocampal neuron and detected SIRT1 and p-ERK1/2 expression, LDH release and cell viability. We found that sirtinol counteracted chIV-induced SIRT1 and p-ERK1/2 upregulation (Figure 5C and 5D, p<0.01 or p<0.001). In addition, primary hippocampal neuron pretreated with sirtinol increased LDH level and decreased cell vibility, indicating that the protective effect of chIV was largely counteracted by sirtinol (Figure 5E and 5F, p<0.05). These data suggesting that ERK1/2 might be one of the downstream of SIRT1 and chIV-induced neuroprotective effect after isoflurane anesthesia could possibly mediate by activating SIRT1/ERK1/2 pathway.

Discussion

In present study, we shown for the first time that chIV pretreatment attenuated isoflurane-induced neurotoxicity and spatial memory impairment in neonatal rats. ChIV pretreatment eliminated the increase of neuroapoptosis and improved the hippocampal dependent spatial memory deficiency following isoflurane anesthesia. Furthermore, the protective effect of chIV after isoflurane exposure possibly mediated by SIRT1/ERK1/2 pathway up-regulation.

Previous researches have demonstrated that at postnatal and early childhood stage, isoflurane anesthesia increased the risk of impairment in learning and memory [1-3]. In our experiment, we found that developmental rats showed less platform crossing, longer escape length, longer escape latency and less time in target quadrant in MWM test after isoflurane exposure. The underlying mechanism might be associated with neuroapoptosis, neuro-inflammation and synaptic plasticity dysfunction [5,6,27]. As a common traditional herbal medicine, chIV had a remarkable effect on anti-apoptosis, inflammation, thrombotic and reduced oxidative stress [19,23,24]. Therefore, we hypothesized that whether chIV had a neuroprotective effect on neonatal rats after isoflurane anesthesia. To further investigate the role of chIV on neonatal rats after isoflurane anesthesia, neonatal rats pretreated with chIV. Our study demonstrated that chIV attenuated neuroapoptosis and PSD 95 decrease in neonatal rats after isoflurane anesthesia. In addition, chIV also reversed hippocampal dependent spatial memory impairment induced by isoflurane suggesting that chIV might provide a neuroprotective effect in newborn rats and improved adolescent spatial memory of rats after their neonatal exposure to isoflurane.

SIRT1 is the closest mammalian homolog of yeast Sir2, a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent histone deacetylase. In recent years, SIRT1 has emerged as a key regulator in multiple neurodegenerative disorders [10,11,29-32], and it also attracted our attention in various fields of disorders such as metabolic disease [33], oncogenesis [31], cardiomyopathy [21], retinal diseases [34] and kidney injury [35]. Accumulating evidence characterize Sirt1 as a survival factor that protects against aging-associated pathologies, including cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders, and, importantly, neurodegeneration. It was reported to be protective against a number of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s disease, through the deacetylation of either prodeath or prosurvival substrates [12-15]. SIRT1 was expressed at high levels in heart, brain, spinal cord, and dorsal root ganglia of mouse embryos [36] especially highly expressed in embryonic brain [31]. Consistent with this notion, many studies verified that SIRT1 in hippocampus regulated gene expression through histone acetylation is an essential component of learning and memory [17,32,37,38]. As an experimental form of synaptic plasticity and a major cellular mechanism underlying learning and memory, long-term potentiation was enhanced by SIRT1 histone acetylation [39]. In addition, investigators found that SIRT1 localizes in the nuclei of pyramidal and granule neurons of the hippocampus, a structure critically involved in cognitive processes [17]. Therefore, SIRT1 showed many important functions during development, influencing brain structure through axon elongation [40], neurite outgrowth [41], and dendritic branching [16]. Lack of SIRT1 impaired short-term and long-term associative memory, which was necessary for normal spatial learning [17]. Recent year a growing body of studies showed that SIRT1 protein expression were alter and resulted in neuronal damage and neuroapoptosis [42,43]. SIRT1 knock-out mice exhibited impairment of long-term potentiation [32]. In the adult brain, SIRT1 can also modulate synaptic plasticity and memory formation [17,18].However, whether SIRT1 involved in isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis in neonatal was remain unknown. In the present study, we reported that the expression of SIRT1 was downregulated after isoflurane anesthesia in P7 rats and primary hippocampal neuron. However, the administration of chIV, attenuated isoflurane-induced SIRT1 deduction and neuroapoptosis which was consistent with numbers of previous studies. These evidence suggested that SIRT1 expression might involve in the setting of neuroapoptosis after isoflurane anesthesia in neonatal rats, which supported the mechanism of the neuroprotective effect of SIRT1 and chIV could attenuate isoflurane-induced neurotoxicity by up-regulating SIRT1 in newborn rats.

As an inhibitor of SIRT1, sirtinol applied in primary hippocampal neuron to verify the protective mechanism of chIV. In present study, sirtinol decreased chIV-induced SIRT1 and p-ERK1/2 upregulation. In addition, sirtinol also counteracted chIV-induced decreased of primary hippocampal neuron apoptosis. It suggested the neuroprotective function of chIV after isoflurane exposure possibly associated with SIRT1/ERK1/2 pathway.

ERK is a member of the MAPK superfamily, which is important and associated with cell membrane receptors and regulative targets [44]. The regulation of MAPK and its upstream and downstream molecular effectors is widespread. Recent years, accumulating evidence has shown that ERK signaling pathway is closely associated with learning and memory [45-47] and has an effect on synaptic plasticity and new dendritic spines formation [48-50]. ERK activation regulates synaptic proteins and plays a positive regulatory role in the induction and maintenance of LTP [51,52], which contributes to neuroprotection [53,54]. In our study, isoflurane decreased p-ERK1/2 expression and increase of neuroapoptosis in developmental hippocampus, suggesting the p-ERK1/2 might play a neuroprotection role in isoflurane anesthesia. Consistent with our study, ketamine and propofol increased neuroapoptosis and suppressed phosphorylated ERK in five-day-old mice [55]. Zhao et al. [29] demonstrated that after brain injury, SIRT1 inhibitor or RNA interference could attenuate activation of ERK. On the other hand, inhibition of ERK activation could reduce SIRT1 expression. In our experiment isoflurane downregulate SIRT1 and decrease p-ERK1/2 activation whereas chIV upregulated SIRT1 and increased p-ERK1/2 activation. These results further revealed the relationship between SIRT1 and ERK1/2 in isoflurane anesthesia at neonatal. However, the role of p-ERK1/2 in chIV-induced neuroprotective effect after isoflurane exposure was remain to investigate and the precious mechanism remained to be further detected in our following experiment.

Taken together, our research demonstrated that chIV protected hippocampal neuron from isoflurane-induced neurotoxicity in neonatal rats and improved adolescent spatial memory of rats after their neonatal exposure to isoflurane. The underlying mechanisms of chIV mediated neuroprotective effect seemed to be associated with activation of SIRT1/ERK1/2 pathway. Our results promoted chIV as a promising novel therapeutic agent for isoflurane induced neurotoxicity and spatial memory deficiency at developmental stage.

Acknowledgements

Our project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers 81571047, 81271233, 81400882, and 81500982) and Science and Technology Projects of Wuhan (grant number 2015060101010036).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Wilder RT, Flick RP, Sprung J, Katusic SK, Barbaresi WJ, Mickelson C, Gleich SJ, Schroeder DR, Weaver AL, Warner DO. Early exposure to anesthesia and learning disabilities in a population-based birth cohort. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:796–804. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000344728.34332.5d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ing C, DiMaggio C, Whitehouse A, Hegarty MK, Brady J, von Ungern-Sternberg BS, Davidson A, Wood AJ, Li G, Sun LS. Long-term differences in language and cognitive function after childhood exposure to anesthesia. Pediatrics. 2012;130:e476–485. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiMaggio C, Sun LS, Li G. Early childhood exposure to anesthesia and risk of developmental and behavioral disorders in a sibling birth cohort. Anesth Analg. 2011;113:1143–1151. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182147f42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brambrink AM, Evers AS, Avidan MS, Farber NB, Smith DJ, Zhang X, Dissen GA, Creeley CE, Olney JW. Isoflurane-induced neuroapoptosis in the neonatal rhesus macaque brain. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:834–841. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d049cd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Creeley CE, Dikranian KT, Dissen GA, Back SA, Olney JW, Brambrink AM. Isoflurane-induced apoptosis of neurons and oligodendrocytes in the fetal rhesus macaque brain. Anesthesiology. 2014;120:626–638. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uchimoto K, Miyazaki T, Kamiya Y, Mihara T, Koyama Y, Taguri M, Inagawa G, Takahashi T, Goto T. Isoflurane impairs learning and hippocampal long-term potentiation via the saturation of synaptic plasticity. Anesthesiology. 2014;121:302–310. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jevtovic-Todorovic V, Hartman RE, Izumi Y, Benshoff ND, Dikranian K, Zorumski CF, Olney JW, Wozniak DF. Early exposure to common anesthetic agents causes widespread neurodegeneration in the developing rat brain and persistent learning deficits. J Neurosci. 2003;23:876–882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-03-00876.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y, Wang F, Liu C, Zeng M, Han X, Luo T, Jiang W, Xu J, Wang H. JNK pathway may be involved in isoflurane-induced apoptosis in the hippocampi of neonatal rats. Neurosci Lett. 2013;545:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2013.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li D, Liu N, Zhao HH, Zhang X, Kawano H, Liu L, Zhao L, Li HP. Interactions between Sirt1 and MAPKs regulate astrocyte activation induced by brain injury in vitro and in vivo. J Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:67. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-0841-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin A, Tegla CA, Cudrici CD, Kruszewski AM, Azimzadeh P, Boodhoo D, Mekala AP, Rus V, Rus H. Role of SIRT1 in autoimmune demyelination and neurodegeneration. Immunol Res. 2015;61:187–197. doi: 10.1007/s12026-014-8557-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paraíso AF, Mendes KL, Santos SH. Brain Activation of SIRT1: role in neuropathology. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;48:681–689. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8459-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houtkooper RH, Pirinen E, Auwerx J. Sirtuins as regulators of metabolism and healthspan. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:225–238. doi: 10.1038/nrm3293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo W, Qian L, Zhang J, Zhang W, Morrison A, Hayes P, Wilson S, Chen T, Zhao J. Sirt1 overexpression in neurons promotes neurite outgrowth and cell survival through inhibition of the mTOR signaling. J Neurosci Res. 2011;89:1723–1736. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang F, Wang S, Gan L, Vosler PS, Gao Y, Zigmond MJ, Chen J. Protective effects and mechanisms of sirtuins in the nervous system. Prog Neurobiol. 2011;95:373–395. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Donmez G, Arun A, Chung CY, McLean PJ, Lindquist S, Guarente L. SIRT1 protects against alpha-synuclein aggregation by activating molecular chaperones. J Neurosci. 2012;32:124–132. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3442-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16.Codocedo JF, Allard C, Godoy JA, Varela-Nallar L, Inestrosa NC. SIRT1 regulates dendritic development in hippocampal neurons. PLoS One. 2012;7:e47073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michan S, Li Y, Chou MM, Parrella E, Ge H, Long JM, Allard JS, Lewis K, Miller M, Xu W, Mervis RF, Chen J, Guerin KI, Smith LE, McBurney MW, Sinclair DA, Baudry M, de Cabo R, Longo VD. SIRT1 is essential for normal cognitive function and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9695–9707. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0027-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao J, Wang WY, Mao YW, Graff J, Guan JS, Pan L, Mak G, Kim D, Su SC, Tsai LH. A novel pathway regulates memory and plasticity via SIRT1 and miR-134. Nature. 2010;466:1105–1109. doi: 10.1038/nature09271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H, Qi J, Li L, Wu T, Wang Y, Wang X, Ning Q. Inhibitory effects of Chikusetsusaponin IVa on lipopolysaccharide-induced pro-inflammatory responses in THP-1 cells. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2015;28:308–317. doi: 10.1177/0394632015589519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.He H, Xu J, Xu Y, Zhang C, Wang H, He Y, Wang T, Yuan D. Cardioprotective effects of saponins from Panax japonicus on acute myocardial ischemia against oxidative stress-triggered damage and cardiac cell death in rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;140:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duan J, Yin Y, Wei G, Cui J, Zhang E, Guan Y, Yan J, Guo C, Zhu Y, Mu F, Weng Y, Wang Y, Wu X, Xi M, Wen A. Chikusetsu saponin IVa confers cardioprotection via SIRT1/ERK1/2 and Homer1a pathway. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18123. doi: 10.1038/srep18123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei N, Zhang C, He H, Wang T, Liu Z, Liu G, Sun Z, Zhou Z, Bai C, Yuan D. Protective effect of saponins extract from Panax japonicus on myocardial infarction: involvement of NF-kappaB, Sirt1 and mitogen-activated protein kinase signalling pathways and inhibition of inflammation. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2014;66:1641–1651. doi: 10.1111/jphp.12291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yuan D, Wan JZ, Deng LL, Zhang CC, Dun YY, Dai YW, Zhou ZY, Liu CQ, Wang T. Chikusetsu saponin V attenuates MPP+-induced neurotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells via regulation of Sirt1/Mn-SOD and GRP78/caspase-12 pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:13209–13222. doi: 10.3390/ijms150813209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dai YW, Zhang CC, Zhao HX, Wan JZ, Deng LL, Zhou ZY, Dun YY, Liu CQ, Yuan D, Wang T. Chikusetsusaponin V attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced liver injury in mice. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2016;38:167–174. doi: 10.3109/08923973.2016.1153109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahmer T, Berger M, Barlette AG, Reck J Jr, Segalin J, Verza S, Ortega GG, Gnoatto SC, Guimaraes JA, Verli H, Gosmann G. Antithrombotic effect of chikusetsusaponin IVa isolated from Ilex paraguariensis (Mate) J Med Food. 2012;15:1073–1080. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2011.0320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li SY, Xia LX, Zhao YL, Yang L, Chen YL, Wang JT, Luo AL. Minocycline mitigates isoflurane-induced cognitive impairment in aged rats. Brain Res. 2013;1496:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang W, Chen X, Zhang J, Zhao Y, Li S, Tan L, Gao J, Fang X, Luo A. Glycyrrhizin attenuates isoflurane-induced cognitive deficits in neonatal rats via its anti-inflammatory activity. Neuroscience. 2016;316:328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen X, Wang W, Zhang J, Li S, Zhao Y, Tan L, Luo A. Involvement of caspase-3/PTEN signaling pathway in isoflurane-induced decrease of self-renewal capacity of hippocampal neural precursor cells. Brain Res. 2015;1625:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2015.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao Y, Luo P, Guo Q, Li S, Zhang L, Zhao M, Xu H, Yang Y, Poon W, Fei Z. Interactions between SIRT1 and MAPK/ERK regulate neuronal apoptosis induced by traumatic brain injury in vitro and in vivo. Exp Neurol. 2012;237:489–498. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qu Y, Zhang J, Wu S, Li B, Liu S, Cheng J. SIRT1 promotes proliferation and inhibits apoptosis of human malignant glioma cell lines. Neurosci Lett. 2012;525:168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tang BL, Chua CE. SIRT1 and neuronal diseases. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:187–200. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herskovits AZ, Guarente L. SIRT1 in Neurodevelopment and brain senescence. Neuron. 2014;81:471–483. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bordone L, Guarente L. Calorie restriction, SIRT1 and metabolism: understanding longevity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:298–305. doi: 10.1038/nrm1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balaiya S, Abu-Amero KK, Kondkar AA, Chalam KV. Sirtuins expression and their role in retinal diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:1–11. doi: 10.1155/2017/3187594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guan Y, Hao CM. SIRT1 and kidney function. Kidney Dis (Basel) 2016;1:258–265. doi: 10.1159/000440967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sakamoto J, Miura T, Shimamoto K, Horio Y. Predominant expression of Sir2α, an NADdependent histone deacetylase, in the embryonic mouse heart and brain1. FEBS Lett. 2004;556:281–286. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)01444-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng HL, Mostoslavsky R, Saito S, Manis JP, Gu Y, Patel P, Bronson R, Appella E, Alt FW, Chua KF. Developmental defects and p53 hyperacetylation in Sir2 homolog (SIRT1)-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10794–10799. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1934713100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fischer A, Sananbenesi F, Wang X, Dobbin M, Tsai LH. Recovery of learning and memory is associated with chromatin remodelling. Nature. 2007;447:178–182. doi: 10.1038/nature05772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levenson JM, O’Riordan KJ, Brown KD, Trinh MA, Molfese DL, Sweatt JD. Regulation of histone acetylation during memory formation in the hippocampus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40545–40559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402229200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li XH, Chen C, Tu Y, Sun HT, Zhao ML, Cheng SX, Qu Y, Zhang S. Sirt1 promotes axonogenesis by deacetylation of Akt and inactivation of GSK3. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;48:490–499. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8437-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sugino T, Maruyama M, Tanno M, Kuno A, Houkin K, Horio Y. Protein deacetylase SIRT1 in the cytoplasm promotes nerve growth factor-induced neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:2821–2826. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hernandez-Jimenez M, Hurtado O, Cuartero MI, Ballesteros I, Moraga A, Pradillo JM, McBurney MW, Lizasoain I, Moro MA. Silent information regulator 1 protects the brain against cerebral ischemic damage. Stroke. 2013;44:2333–2337. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang P, Xu TY, Guan YF, Tian WW, Viollet B, Rui YC, Zhai QW, Su DF, Miao CY. Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase protects against ischemic stroke through SIRT1-dependent adenosine monophosphate-activated kinase pathway. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:360–374. doi: 10.1002/ana.22236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peng S, Zhang Y, Zhang J, Wang H, Ren B. ERK in learning and memory: a review of recent research. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11:222–232. doi: 10.3390/ijms11010222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sweatt JD. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in synaptic plasticity and memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2004;14:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Feld M, Dimant B, Delorenzi A, Coso O, Romano A. Phosphorylation of extra-nuclear ERK/MAPK is required for long-term memory consolidation in the crab chasmagnathus. Behav Brain Res. 2005;158:251–261. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanderson TM, Hogg EL, Collingridge GL, Correa SA. Hippocampal metabotropic glutamate receptor long-term depression in health and disease: focus on mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. J Neurochem. 2016;139(Suppl 2):200–214. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Selcher JC. A Necessity for MAP kinase activation in mammalian spatial learning. Lear Mem. 1999;6:478–490. doi: 10.1101/lm.6.5.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Impey S, Obrietan K, Storm DR. Making new connections: role of ERK/MAP kinase signaling in neuronal plasticity. Neuron. 1999;23:11–14. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80747-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.English JD, Sweatt JD. A requirement for the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade in hippocampal long term potentiation. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19103–19106. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kato A, Fukazawa Y, Ozawa F, Inokuchi K, Sugiyama H. Activation of ERK cascade promotes accumulation of Vesl-1S/Homer-1a immunoreactivity at synapses. Molecular Brain Research. 2003;118:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shu Y, Xiao B, Wu Q, Liu T, Du Y, Tang H, Chen S, Feng L, Long L, Li Y. The Ephrin-A5/EphA4 interaction modulates neurogenesis and angiogenesis by the p-Akt and p-ERK pathways in a mouse model of TLE. Mol Neurobiol. 2016;53:561–576. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-9020-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen T, Liu W, Chao X, Qu Y, Zhang L, Luo P, Xie K, Huo J, Fei Z. Neuroprotective effect of osthole against oxygen and glucose deprivation in rat cortical neurons: involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Neuroscience. 2011;183:203–211. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guerra B, Diaz M, Alonso R, Marin R. Plasma membrane oestrogen receptor mediates neuroprotection against beta-amyloid toxicity through activation of Raf-1/MEK/ERK cascade in septal-derived cholinergic SN56 cells. J Neurochem. 2004;91:99–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02695.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Straiko MM, Young C, Cattano D, Creeley CE, Wang H, Smith DJ, Johnson SA, Li ES, Olney JW. Lithium protects against anesthesia-induced developmental neuroapoptosis. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:862–868. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819b5eab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]