Abstract

Lateral meniscus tears are commonly encountered by orthopaedic surgeons. Despite efforts to repair and preserve the meniscus, meniscectomy is occasionally required to treat irreparable tears. The resulting lateral meniscus deficiency leads to increased tibiofemoral contact pressures and ultimately early osteoarthritic changes in the knee. Lateral meniscal allograft transplant (LMAT) has been proposed as a way to restore the lateral meniscus–deficient knee to its native form. Although several techniques for LMAT have been proposed, osseous fixation has demonstrated increased stability, improved outcomes, and improved long-term survival. This article presents a technique for LMAT using bone plugs and standard arthroscopic portals.

Lateral meniscus tears are frequently encountered in orthopaedics and remain the most common associated injury to occur with an anterior cruciate ligament tear.1, 2 Despite efforts to repair and preserve the meniscus, meniscectomy may be required to treat an irreparable tear.3 After lateral meniscectomy, the total contact area is decreased, resulting in significantly increased tibiofemoral contact pressures and ultimately early osteoarthritic changes in the knee.4, 5, 6 Lateral meniscal allograft transplant (LMAT) has been proposed as a way to restore the lateral meniscus–deficient knee to its native form. Biomechanical studies have shown that LMAT can restore lateral tibiofemoral contact pressures to near normal values.7 Furthermore, significantly improved functional scores and activity levels have been reported at greater than 2 years following LMAT.8, 9

Several techniques have been proposed for LMAT, including bone trough, bone plugs, and soft-tissue techniques.10, 11 Osseous fixation of the anterior and posterior roots has demonstrated increased stability, improved outcomes, and long-term survival.12, 13, 14, 15 We present a technique for LMAT using bone plugs. This technique allows for osseus fixation through standard arthroscopy portals with limited soft-tissue dissection.

Surgical Technique

Indications and Contraindications

The indications and contraindications for this procedure are outlined in Table 1. The ideal candidate is a young patient with joint line pain resulting from total lateral meniscectomy, minimal cartilage degeneration, and normal alignment.16, 17 Although prophylactic transplantation has been considered for asymptomatic patients, this is not routinely performed.18 The main contraindication to LMAT is severe articular cartilage damage in the meniscal-deficient compartment.19

Table 1.

Indications and Contraindications to Lateral Meniscal Allograft Transplant17

| Absolute Indications | Indications | Contraindications | Absolute Contraindications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Complete meniscal deficiency in a young, healthy patient with good articular cartilage status (grade II or better) | Complete meniscal deficiency in a young, healthy patient with grade III or better articular cartilage | Age >50 years | Advanced, diffuse chondral degeneration |

| Skeletal immaturity | Unaddressed cruciate insufficiency | ||

| Synovial disease or inflammatory arthritis | Unaddressed malalignment | ||

| Obesity (body mass index >35) |

Graft Selection and Preparation

Our method for LMAT is demonstrated in Video 1. Fresh-frozen and nonirradiated grafts are preferred for LMAT.20 Preoperative allograft sizing is essential to ensure that the graft can be anatomically reduced within the donor lateral compartment. The method used was originally described by Pollard et al.21 This method has a reported size mismatch of less than 5%, and its use has previously been described for medial meniscus allograft transplantation using a bone plug technique.22

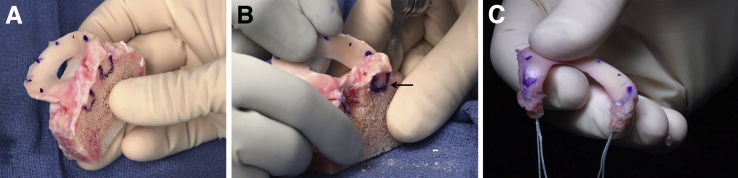

Special equipment is required for this procedure (Table 2). An oscillating saw, rongeur, and a rasp are used to precisely create 7-mm cylindrical bone plugs at the anterior and posterior meniscal roots (Fig 1 A and B). Sizing is confirmed using the sizing block (Arthrex, Naples, FL) before proceeding to ensure easy reduction into the 8-mm tibial sockets. A self-locking traction suture is then advanced from distal to proximal, through the meniscus and then back from proximal to distal. This suture is used for transtibial pull-through fixation at the anteromedial tibia (Fig 1C).

Table 2.

Equipment Required to Perform a Lateral Meniscus Allograft Transplantation Using the Bone Plug Technique

| Special Equipment required for lateral meniscal allograft transplantation |

| Graft preparation: |

| - Oscillating saw |

| - No. 15 blade knife |

| - Ronguer |

| - No. 2 FiberWire with Straight Needle (×2) |

| Transtibial meniscal root fixation: |

| - Variable angle transtibial meniscal root drill guide |

| - 8-mm FlipCutter Retrograde Reamer |

| - No. 2 TigerStick Suture (x2) |

| - KingFisher Retriever/Grasper |

| - 5.5-mm SwiveLock Anchor |

| Meniscal suturing: |

| - No. 2-0 FiberWire Meniscal Repair Needles |

| - Meniscal Repair Joystick Instrument Set System |

| - Spoon |

Fig 1.

Lateral meniscus allograft transplant graft preparations (A) Size-matched, fresh-frozen graft. (B) Sizing bone blocks to 7 mm (solid arrow). (C) Final graft after placement of fixation sutures.

Patient Positioning and Visualization

In addition to standard arthroscopy instrumentation, additional specialized equipment is required to perform this technique (Table 2). The patient is positioned supine. Bilateral examination of the knee is performed to determine ligament stability and range of motion. The operative extremity is prepped and draped in the usual fashion for knee arthroscopy. A vertical anterolateral viewing portal is established. The knee is positioned in figure-of-4 while establishing the anteromedial portal under direct visualization. A spinal needle is used to confirm the correct portal trajectory allowing easy access to the lateral meniscal roots and peripheral capsule prior to incision. When performing an LMAT, adequate visualization and easy instrument passage are critical. Visualization is optimized using a shaver and cautery to remove part of the patellar fat pad. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed paying special attention to the amount of remaining meniscus present and the condition of the cartilage for prognostic purposes.

Graft Site Preparation

Donor site preparation is performed systematically. The remaining meniscus is debrided using a 3.5-mm shaver (Arthrex) followed by a meniscal rasp. A 1- to 2-mm remnant of stable bleeding meniscus is left in situ. Secure fixation to the functional meniscal rim in conjunction with anterior and posterior horn fixation is capable of withstanding hoop stresses under axial load.23 The anatomic attachment sites for the meniscal roots are identified and marked with an Arthrowand (Smith & Nephew, ArthroCare, Austin, TX). A calibrated probe is inserted and a distance of 18 mm or greater is confirmed. This ensures a 10-mm bony bridge remains after 8-mm-diameter sockets are drilled for the anterior and posterior bone blocks.

Creation of Tibial Bone Sockets

After adequate visualization has been obtained, the posterior tibial sockets is created. A 2- to 3-cm incision is made just proximal and medial to the tibial tuberosity. Dissection is carried down to the bone. It is critical to have complete visualization of the anterior tibia to prevent tunnel coalition. The use of a tibial guide that is precontoured to the femoral condyle ensures accurate tunnel placement with minimal torque.

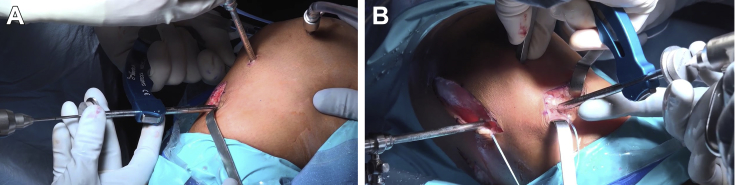

The tibial drill guide is inserted through the anterolateral portal and visualized through the anteromedial portal (Fig 2A). The guide tip is placed at the center of the posterior meniscal root footprint just off the articular surface. The guide is set to 50° angulation. A 2.4-mm wire is advanced through the inner cannula to the tip of the guide. The drill guide is then carefully removed. The outer cannula is impacted into the anterior cortex of the tibia. A 3.5-mm-diameter FlipCutter (Arthrex) is drilled through the cannula in the same trajectory as the 2.5-mm wire. The FlipCutter (Arthrex) is converted to an 8.0-mm reamer under direct arthroscopic visualization. The tibia is retro-drilled 10 mm. The FlipCutter is advanced back into the joint, converted back to a 3.5-mm diameter drill, and removed from the tibia. A no. 2 TigerStick suture (Arthrex) is advanced through the tibial tunnel and the FiberWire passing suture is retrieved through the lateral portal.

Fig 2.

Arthroscopy being performed on a patient's right knee. Demonstrating anterior and posterior bone tunnel creation. (A) Posterior tunnel drilling: the tibial guide is set to 50° and inserted through the anterolateral portal; the arthroscope is positioned in the anteromedial portal. (B) Anterior tunnel drilling: the tibial guide is set to 70° and inserted through the anteromedial portal; the arthroscope is positioned in the anterolateral portal.

The anterior meniscal root transtibial socket requires careful planning to prevent tunnel coalition. Four steps are performed to ensure this does not occur. First, the transtibial drill guide is positioned in the anteromedial portal while viewing through the anterolateral portal (Fig 2B). Second, the angulation on the guide is changed from 50° to 70°. Third, the tibial start point is directly visualized to be superomedial to the previous drill hole on the anteromedial face of the tibial cortex. If the anterior tibial cortex cannot be easily visualized, the incision is enlarged. Last, the intraarticular position is 18 mm anterior to the center of the posterior tunnel (or 14 mm anterior to the anterior edge of the previously drilled tunnel). If these steps are performed, tunnel coalition will be avoided. The anterior tunnel is created similarly to the posterior tunnel with an 8-mm FlipCutter reamer (Arthrex) retro-reamed to a depth of 10 mm.

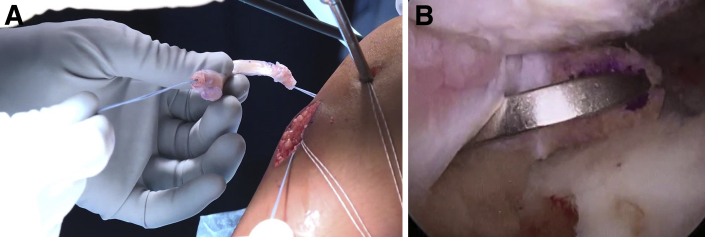

Graft Passage

In preparation for graft passage, the anterior and posterior shuttling sutures are retrieved through the anterolateral portal together to prevent soft-tissue bridge formation. Alternatively, a small cannula can be used to pass the sutures avoiding a soft tissue bridge and then removed. The anterolateral portal is expanded to 2 to 3 cm in size to allow easy passage of the graft and instrumentation during implantation. The posterior root sutures are then shuttled through the tibial tunnel leaving the graft extra-articular (Fig 3A). These sutures are then used to apply mild traction while the posterior root bone block and graft are advanced intra-articular using a KingFisher retriever/grasper (Arthrex). While viewing from the anteromedial portal, the bone block is reduced into the poster socket (Fig 3B). This is then repeated anteriorly. The anterior root sutures are shuttled through the tibia. Tension is applied, and the anterior bone block is advanced into the joint using a KingFisher retriever/grasper. The free suture ends are clamped over the anterior tibial cortex to maintain tension during meniscal suturing.

Fig 3.

Passage of the graft into the right knee joint. (A) The posterior root sutures have been passed transtibial. Traction is applied to assist with graft reduction. (B) A KingFisher retriever/grasper is then used to advance the bone block to an intra-articular position near the tunnel.

Meniscal Suturing

A 5-cm posterolateral incision is made from the tip of the fibula proximally in line with the iliotibial band. Blunt dissection is carried down to expose the iliotibial band and the biceps femoris. The interval between these landmarks is developed exposing the gastrocnemius muscle. A finger is placed anterior to the gastrocnemius, and the ankle is plantarflexed and dorsiflexed to confirm accurate positioning over the posterolateral capsule. A spoon is placed into this position. Blunt dissection is performed to connect the posterolateral and anterolateral incisions subcutaneously. The anterior sutures will be retrieved in this interval. Zone-specific cannulas are used to pass no. 2-0 FiberWire Meniscus Repair Needles (Arthrex). While viewing from the anterolateral portal, the meniscus is reduced and a suture is passed at the midpoint of the meniscus marked during preparation. Prior to tying, a probe is inserted and accurate reduction is confirmed. Multiple superior and inferior vertical mattress sutures are then placed until the meniscus is stable throughout its circumference.

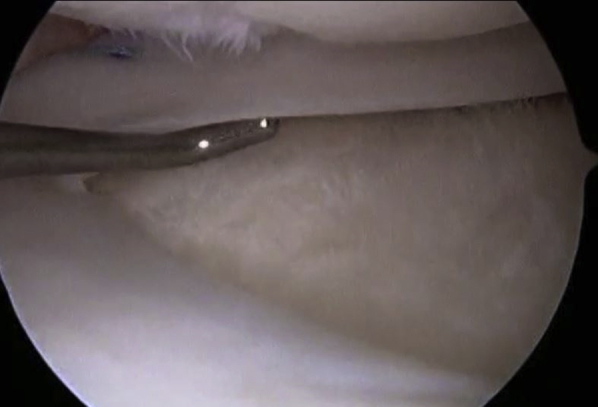

Tibial Fixation of Meniscal Root Sutures

Tibial fixation is obtained with a 4.75-mm BioComposite SwiveLock anchor (Arthrex) with the leg in full extension. A 2.4-mm guide pin is drilled 1 cm distal to the 2 drill holes through the anteromedial tibial cortex. This pin is over-reamed with a 4.5-mm reamer to a depth of 20 mm. The tibial cortex is tapped using a 4.5-mm tap. The 4 free ends of the meniscal sutures are passed through the eyelet of the SwiveLock anchor (Arthrex) and tension is applied. Accurate reduction is confirmed arthroscopically and the anchor is advanced into the reamed/taped tibial hole (Fig 4).

Fig 4.

Lateral meniscus allograft after transplantation viewing from the anterolateral portal.

Rehabilitation

Weight bearing in full extension is limited to partial weight bearing, and knee flexion is limited to 90° until 4 weeks after surgery. After 4 weeks, use of the brace is discontinued and the patient may begin full weight bearing and full knee range of motion. Knee loading at flexion angles greater than 90° is not allowed until 4 months postoperatively, at which point patients are typically allowed to return to activity as tolerated.

Discussion

Complete lateral meniscectomy has been shown to result in early osteoarthritis and functional limitations. This is thought to occur as a result of the increased tibiofemoral contact pressures in the lateral compartment.24 LMAT has been shown to reduce these contact pressures back to near normal values.7 Furthermore, clinical outcomes following LMAT have demonstrated satisfactory functional outcome with acceptable long-term survival.12, 25 LMAT is a viable surgical option for the lateral meniscus–deficient knee and has been shown to be a safe and effective procedure.12, 26

Although the overall outcomes following LMAT are promising, poor outcomes have been reported in the presence of concomitant pathology, including full-thickness cartilage lesions. These associated pathologies can result in rapid failure of the LMAT and often result in revision surgery.27 Similarly, when an isolated ACL reconstruction is performed in a meniscus-deficient knee, the meniscal deficiency has been shown to cause instability and may cause increased graft strain following ACL in reconstruction.28 These findings highlight the importance of adopting strict surgical indications and simultaneously correcting concomitant pathology (osteotomies, ligament reconstruction, or cartilage procedures) where indicated to optimize outcomes and graft longevity.

Several surgical techniques have been described for LMAT including the soft tissue, bone trough, and bone plug techniques.10, 11 The soft tissue technique has the advantage of being less technically challenging for graft preparation and passage when compared to osseous techniques. However, cadaveric testing has shown that bone fixation more closely reproduces the normal function of the meniscus.29 In addition, the rate of satisfactory functional outcomes following LMAT with bony fixation is significantly greater than that reported for soft-tissue fixation.30 Advantages and disadvantages of the bone plug technique can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Bone Plug Technique for Lateral Meniscal Allograft Transplant

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Osseous integration | Requires accurate bone plug preparation |

| Minimally invasive | Bone plug reduction is technically challenging |

| Cortical fixation | Anatomic spacing between roots must be determined arthroscopically |

Currently the most widely used technique for LMAT is the bone trough technique. This technique maintains both the anterior and posterior meniscal roots on a single bone trough, providing inherent stability and anatomic spacing.13, 14 However, this technique necessitates an arthrotomy, requires precise bone resection, and ultimately relies on a compression fit.10, 31

The bone plug technique described in this article maintains the advantages of osseous integration and graft stability while providing several advantages (Table 4). First, it can be performed arthroscopically through small incisions. Second, cortical fixation is obtained on the anteromedial tibia to prevent graft displacement. Third, this technique provides technical familiarity to surgeons currently performing medial meniscus allograft transplantation using bone plugs and transtibial meniscal root repairs. LMAT is a viable option for the lateral meniscus–deficient knee. LMAT provides patients with improved activity levels and reduced pain scores. Optimal outcomes are achieved when the surgical indications are followed and concomitant pathology is addressed. The bone plug technique allows for osseous integration of the LMAT through a minimally invasive technique.

Table 4.

Pearls and Pitfalls

| Pearls | Pitfalls |

|---|---|

| Create a large anterolateral portal to ensure easy passage of instrumentation and graft throughout the procedure | Failure to adequately expose the posterolateral capsule and protect posterior structures; places neurovascular structures at risk of injury |

| Leave a 1-mm peripheral rim of normal meniscus to aid in obtaining secure allograft fixation and prevent extrusion | Transtibial fixation in patients with open physis can lead to growth arrest |

| Prevent tunnel coalition by exposing the anterior tibial cortex, drill from different portals, set the drill guide to different angles, and maximize the distance between anatomic root positions | Fixation failure can occur if the patient is not able to comply with the rehabilitation protocol |

| With the meniscal bone blocks reduced, clamp the transtibial sutures and place 1 (or 2) central sutures through the premarked meniscal body; confirm an accurate reduction before knot-tying | Failure to identify/address concomitant pathology (i.e., ligamentous instability; full-thickness cartilage defects) will lead to poor outcome |

Footnotes

The authors report the following potential conflicts of interest or sources of funding: B.A.L. reports grants and personal fees from Arthrex, other from International Society of Arthroscopy, Knee Surgery and Orthopaedic Sports Medicine Representative, other from the Arthroscopy Association of North America, grants from Biomet, other from CORR, other from Journal of Knee Surgery, other from Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, and Arthroscopy, grants and other from Stryker, and other from VOT solutions, outside the submitted work. M.J.S. reports personal fees from Arthrex; personal fees from Stryker, outside the submitted work; and American Journal of Sports Medicine: editorial or governing board. A.J.K. reports personal fees from Arthrex, personal fees from Arthritis Foundation, personal fees from Histogenics, outside the submitted work. Full ICMJE author disclosure forms are available for this article online, as supplementary material.

Supplementary Data

Lateral meniscus allograft transplantation (LMAT) using the bone plug technique. A size-matched, fresh-frozen graft is obtained from the tissue bank. The anterior and posterior horns are marked, and 8-mm bone blocks are grossly created with an oscillating saw. These are then precisely adjusted to create 7-mm cylindrical blocks. Self-locking traction sutures are placed for transtibial pull-through fixation at the anteromedial tibia. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed and the recipient site is prepared. A combination of biters, a shaver, and a rasp are used to create a bleeding outer rim. The anatomic attachment sites for the meniscal roots are identified and marked. The posterior tunnel is created with the tibial guide set to 50° and inserted through the anterolateral portal while viewing through the anteromedial portal. A 2.4-mm wire is advanced into place followed by a 3.5-mm FlipCutter drill that is deployed into an 8-mm reamer. A 10-mm tunnel is then retro-reamed. A TigerStick suture is passed and is used for transtibial passage of the posterior horn sutures. The anterior tunnel is created with the tibial guide set to 70 decrees and placed into the anteromedial portal while viewing from anterolateral. The tunnel is then created in a similar fashion to the posterior tunnel with an 8 mm FlipCutter reamer and passage of a TigerStick. The posterior bone block suture is shuttled through the tibial tunnel. A king Fischer is then used to advance the bone block intra-articular while tension is applied to the transtibial suture. The posterior bone block is reduced into the socket. This process is repeated for the anterior bone block. A posterolateral exposure is performed and a spoon retractor is placed of in the interval anterior to the gastrocnemius overlying the posterior capsule. Circumferential meniscal sutures are placed using an inside-out technique. The meniscal roots are then secured into place with a SwiveLock anchor. A probed is inserted into the lateral compartment and the meniscal allograft is assessed. An anatomic reduction with stable fixation has been obtained.

References

- 1.Englund M., Guermazi A., Gale D. Incidental meniscal findings on knee MRI in middle-aged and elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1108–1115. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kilcoyne K.G., Dickens J.F., Haniuk E., Cameron K.L., Owens B.D. Epidemiology of meniscal injury associated with ACL tears in young athletes. Orthopedics. 2012;35:208–212. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20120222-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeong H.J., Lee S.H., Ko C.S. Meniscectomy. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2012;24:129–136. doi: 10.5792/ksrr.2012.24.3.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pengas I.P., Assiotis A., Nash W., Hatcher J., Banks J., McNicholas M.J. Total meniscectomy in adolescents: A 40-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:1649–1654. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B12.30562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fairbanks T. Knee joint changes after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1948;30:664–670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paxton E.S., Stock M.V., Brophy R.H. Meniscal repair versus partial meniscectomy: A systematic review comparing reoperation rates and clinical outcomes. Arthroscopy. 2011;27:1275–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDermott I.D., Lie D.T., Edwards A., Bull A.M., Amis A.A. The effects of lateral meniscal allograft transplantation techniques on tibio-femoral contact pressures. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2008;16:553–560. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0503-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaPrade R.F., Wills N.J., Spiridonov S.I., Perkinson S. A prospective outcomes study of meniscal allograft transplantation. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:1804–1812. doi: 10.1177/0363546510368133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sekiya J.K., West R.V., Groff Y.J., Irrgang J.J., Fu F.H., Harner C.D. Clinical outcomes following isolated lateral meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:771–780. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chahla J., Olivetto J., Dean C.S., Serra Cruz R., LaPrade R.F. Lateral meniscal allograft transplantation: The bone trough technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5:e371–e377. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spalding T., Parkinson B., Smith N.A., Verdonk P. Arthroscopic meniscal allograft transplantation with soft-tissue fixation through bone tunnels. Arthrosc Tech. 2015;4:e559–e563. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim J.M., Bin S.I., Lee B.S. Long-term survival analysis of meniscus allograft transplantation with bone fixation. Arthroscopy. 2017;33:387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2016.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paletta G.A., Jr., Manning T., Snell E., Parker R., Bergfeld J. The effect of allograft meniscal replacement on intraarticular contact area and pressures in the human knee. A biomechanical study. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:692–698. doi: 10.1177/036354659702500519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen M.I., Branch T.P., Hutton W.C. Is it important to secure the horns during lateral meniscal transplantation? A cadaveric study. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:174–181. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(96)90007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alhalki M.M., Howell S.M., Hull M.L. How three methods for fixing a medial meniscal autograft affect tibial contact mechanics. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27:320–328. doi: 10.1177/03635465990270030901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garrett J.C., Steensen R.N. Meniscal transplantation in the human knee: A preliminary report. Arthroscopy. 1991;7:57–62. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(91)90079-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Noyes F.R., Barber-Westin S.D. Long-term survivorship and function of meniscus transplantation. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:2330–2338. doi: 10.1177/0363546516646375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson D.L., Bealle D. Meniscal allograft transplantation. Clin Sports Med. 1999;18:93–108. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70132-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cole B.J., Carter T.R., Rodeo S.A. Allograft meniscal transplantation: Background, techniques, and results. Instr Course Lect. 2003;52:383–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodeo S.A., Seneviratne A., Suzuki K., Felker K., Wickiewicz T.L., Warren R.F. Histological analysis of human meniscal allografts. A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:1071–1082. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200008000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pollard M.E., Kang Q., Berg E.E. Radiographic sizing for meniscal transplantation. Arthroscopy. 1995;11:684–687. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(95)90110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dean C.S., Olivetto J., Chahla J., Serra Cruz R., LaPrade R.F. Medial meniscal allograft transplantation: The bone plug technique. Arthrosc Tech. 2016;5:e329–e335. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2016.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verdonk P., Depaepe Y., Desmyter S. Normal and transplanted lateral knee menisci: Evaluation of extrusion using magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12:411–419. doi: 10.1007/s00167-004-0500-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perez-Blanca A., Espejo-Baena A., Amat Trujillo D. Comparative biomechanical study on contact alterations after lateral meniscus posterior root avulsion, transosseous reinsertion, and total meniscectomy. Arthroscopy. 2016;32:624–633. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2015.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chalmers P.N., Karas V., Sherman S.L., Cole B.J. Return to high-level sport after meniscal allograft transplantation. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verdonk P.C., Demurie A., Almqvist K.F., Veys E.M., Verbruggen G., Verdonk R. Transplantation of viable meniscal allograft. Survivorship analysis and clinical outcome of one hundred cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:715–724. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.01344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parkinson B., Smith N., Asplin L., Thompson P., Spalding T. Factors Predicting Meniscal Allograft Transplantation Failure. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4 doi: 10.1177/2325967116663185. 2325967116663185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shelbourne K.D., Gray T. Results of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction based on meniscus and articular cartilage status at the time of surgery. Five- to fifteen-year evaluations. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:446–452. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280040201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang H., Gee A.O., Hutchinson I.D. Bone plug versus suture-only fixation of meniscal grafts: Effect on joint contact mechanics during simulated gait. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:1682–1689. doi: 10.1177/0363546514530867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rodeo S.A. Meniscal allografts—Where do we stand? Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:246–261. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290022401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee S.R., Kim J.G., Nam S.W. The tips and pitfalls of meniscus allograft transplantation. Knee Surg Relat Res. 2012;24:137–145. doi: 10.5792/ksrr.2012.24.3.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Lateral meniscus allograft transplantation (LMAT) using the bone plug technique. A size-matched, fresh-frozen graft is obtained from the tissue bank. The anterior and posterior horns are marked, and 8-mm bone blocks are grossly created with an oscillating saw. These are then precisely adjusted to create 7-mm cylindrical blocks. Self-locking traction sutures are placed for transtibial pull-through fixation at the anteromedial tibia. A diagnostic arthroscopy is performed and the recipient site is prepared. A combination of biters, a shaver, and a rasp are used to create a bleeding outer rim. The anatomic attachment sites for the meniscal roots are identified and marked. The posterior tunnel is created with the tibial guide set to 50° and inserted through the anterolateral portal while viewing through the anteromedial portal. A 2.4-mm wire is advanced into place followed by a 3.5-mm FlipCutter drill that is deployed into an 8-mm reamer. A 10-mm tunnel is then retro-reamed. A TigerStick suture is passed and is used for transtibial passage of the posterior horn sutures. The anterior tunnel is created with the tibial guide set to 70 decrees and placed into the anteromedial portal while viewing from anterolateral. The tunnel is then created in a similar fashion to the posterior tunnel with an 8 mm FlipCutter reamer and passage of a TigerStick. The posterior bone block suture is shuttled through the tibial tunnel. A king Fischer is then used to advance the bone block intra-articular while tension is applied to the transtibial suture. The posterior bone block is reduced into the socket. This process is repeated for the anterior bone block. A posterolateral exposure is performed and a spoon retractor is placed of in the interval anterior to the gastrocnemius overlying the posterior capsule. Circumferential meniscal sutures are placed using an inside-out technique. The meniscal roots are then secured into place with a SwiveLock anchor. A probed is inserted into the lateral compartment and the meniscal allograft is assessed. An anatomic reduction with stable fixation has been obtained.