Abstract

Background

A methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) program to curb the dual epidemics of HIV/AIDS and drug use has been administered by China since 2004. Little is known regarding the geographic heterogeneity of HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections among MMT clients in the resource-constrained context of Chinese provinces, such as Guangxi. This study aimed to characterize the geographic distribution patterns and co-clustered epidemic factors of HIV, HCV and co-infections at the county level among drug users receiving MMT in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, located in the southwestern border area of China.

Methods

Baseline data on drug users’ demographic, behavioral and biological characteristics in the MMT clinics of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region during the period of March 2004 to December 2014 were obtained from national HIV databases. Residential addresses were entered into a geographical information system (GIS) program and analyzed for spatial clustering of HIV, HCV and co-infections among MMT clients at the county level using geographic autocorrelation analysis and geographic scan statistics.

Results

A total of 31,015 MMT clients were analyzed, and the prevalence of HIV, HCV and co-infections were 13.05%, 72.51% and 11.96% respectively. Both the geographic autocorrelation analysis and geographic scan statistics showed that HIV, HCV and co-infections in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region exhibited significant geographic clustering at the county level, and the Moran’s I values were 0.33, 0.41 and 0.30, respectively (P < 0.05). The most significant high-risk overlapping clusters for these infections were restricted to within a 10.95 km2 radius of each of the 13 locations where P county was the cluster center. These infections also co-clustered with certain characteristics, such as being unmarried, having a primary level of education or below, having used drugs for more than 10 years, and receptive sharing of syringes with others. The high-risk clusters for these characteristics were more likely to reside in the areas surrounding P county.

Conclusions

HIV, HCV and co-infections among MMT clients in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region all presented substantial geographic heterogeneity at the county level with a number of overlapping significant clusters. The areas surrounding P county were effective in enrolling high-risk clients in their MMT programs which, in turn, might enable people who inject drugs to inject less, share fewer syringes, and receive referrals for HIV or HCV treatment in a timely manner.

Keywords: Spatial distribution, HIV, HCV, Co-infections, Drug users, Methadone maintenance treatment

Background

HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections are major global public health concerns, with overlapping routes of transmission, populations most affected and geographical areas. Data from 2014 suggested that more than 36.9 million people worldwide were living with HIV [1], 115 million people were estimated to be HCV antibody-positive [2], and approximately 2.3 million were estimated to have HIV/HCV co-infection, of whom 59% were people who inject drugs (PWID) [3]. Similar to other oversea countries, China has witnessed the fastest-growing HIV and HCV epidemics fueled by injecting drug users (IDUs) over the past three decades and is experiencing the highest burden of these infections in PWID at present [4–6]. Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT) programs were first initiated in China as a small pilot project of only eight sites serving 1029 drug users in 2004. Since then, it has rapidly expanded into a nationwide program covering 738 clinics and serving some 344,254 heroin users by the end of 2011, which accounted for approximately 30% of registered IDUs in China [7, 8]. The MMT program in China is believed to have made impressive progress in HIV infection and drug use among PWID [7] as a result of offering various ancillary services, including testing for HIV, syphilis and HCV, psychosocial support, and referrals for the treatment of HIV, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted diseases.

Because it borders the drug-trafficking route known as the ‘Golden Triangle’ and connects China with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (referred to hereafter as ‘Guangxi’) detected the first outbreak of HIV-1 infection among IDUs in 1996, and transmission through IDUs accounted for 69% of reported HIV cases in 2003, with the second-highest accumulated number of HIV cases in China since 2009 [9–11]. Guangxi therefore launched an MMT program in 2004 as one of the first eight national MMT pilot clinics [12], covering 72 clinics serving more than 30,000 heroin users by the end of 2014. Numerous studies conducted in China [13–16] showed that variations toward the prevalence of HIV and HCV infections differed dramatically across geographic locations. Nevertheless, the spatial distribution of these infections among MMT clients in border areas of China, such as Guangxi, is poorly understood, and most previously published studies [17–19] have concentrated on descriptive analysis. These findings could not visualize the geographic heterogeneity of these infections and detect the presence and location of a cluster in confined regions. We therefore undertook a spatial analysis of the prevalence of HIV and HCV infections among MMT clients from baseline data of treatment between 2004 and 2014, to characterize the geographic distribution patterns and co-clustered epidemic factors of HIV and HCV infections among drug injectors receiving MMT. This study might also have critical implications for policy-making and resource allocation based on the needs of each region, as well as for future MMT program implementation.

Methods

Study area

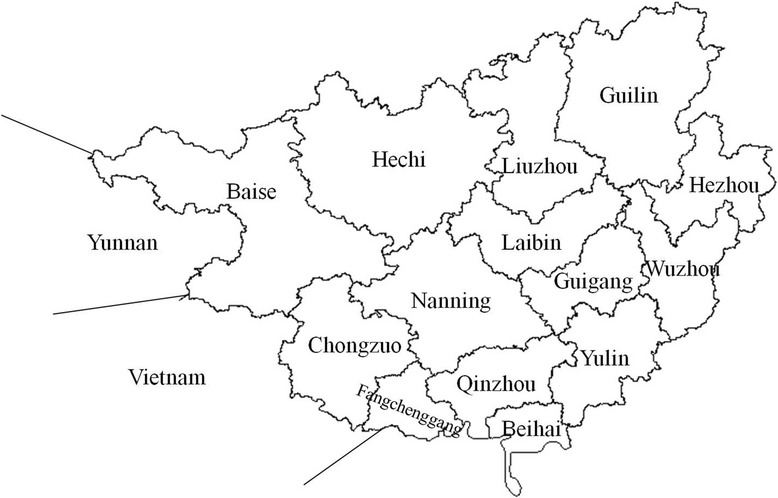

The study site is located in Guangxi, one of the areas most severely affected by HIV/AIDS in China, along with neighboring areas such as Vietnam and Yunnan (Fig. 1). Guangxi, which is located on the southwestern coast of China (104.26° ~ 112.04°E, 20.54° ~ 26.24°N), has an area of 236.7 thousand square kilometers and a population of approximately 52.82 million and encompasses 14 cities, 7 county level cities, 12 autonomic counties and 55 counties (Guangxi Statistical Yearbook in 2015). We examined the city-governed region and designated the others as county-level areas; there were thus 88 county-level areas in our study.

Fig. 1.

The location of Guangxi Autonomous Region, China

Study population and data collection

Since the Chinese National Comprehensive AIDS Response Policy and the ‘Four Frees and One Care’ program (‘four frees’ refers to free HIV voluntary counseling and testing, free antiretroviral treatment for rural HIV patients and poor urban patients, free antiretroviral treatment for pregnant women living with HIV/AIDS, and free schooling for orphaned children of AIDS patients; ‘one care’ refers to financial subsidies for low-income AIDS patients and their families) were launched in 2003 [20], the Chinese Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (China CDC) has established national HIV databases. These cohort study databases can be used to study the prevalence of HIV and HCV infections among MMT clients, and details on the eligibility criteria to participate in the national MMT program have been reported elsewhere [7, 12, 21].

All clients attending the 72 MMT clinics of Guangxi from March 2004 to December 2014 were selected as our study population. Baseline data were collected upon inclusion in the MMT program using an interview questionnaire. Demographic characteristics focused on gender, residential address, ethnicity, marital status, occupation, education, and living status. Drug use questions focused on the initial age and length of drug use, current drugs injected and substances used, method of drug-taking, injection frequency, and syringe sharing. Biological data included urine morphine testing and HIV and HCV testing. Most of the data were self-reported by clients, such as demographic characteristics and drug use questions. Only MMT clients with both HIV or HCV infection and a residential address were analyzed.

A total of 35,387 records (35,008 clients) from 2004 to 2014 were obtained from the baseline database of the 72 MMT clinics in Guangxi. We excluded 3993 records without HIV or HCV testing results and another 379 repeated records; therefore, approximately 31,015 MMT clients were included in our study, which accounted for 88.59% (31,015/35,008) of all MMT clients. To exclude the possibility that the exclusion of clients unmasked correlations among the remaining observations, we compared included clients (N = 31,015) and excluded clients (N = 4372) for all variables, and no differences were found between these groups (not shown in this report).

Laboratory methods

Urine samples were collected from all participants for morphine testing with colloidal gold diagnostics, and a positive urine result was indicative of a current heroin user. Blood samples were collected from all participants for HIV and HCV serologic testing with an enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay (ELISA). Western blot testing was conducted to confirm positive HIV ELISA results. All clients with HIV- and HCV-positive results received counseling and referral to the local China CDC, based on the city/county level of the client’s residence, for follow-up testing and treatment. Seronegative clients were also advised to proceed for follow-up testing in the future as clinically indicated.

Statistical analysis

Spatial analysis was initiated by geolocating residential addresses of MMT clients using electronic maps of Guangxi (Bureau of Surveying and Mapping, Guangxi, China). We confirmed that all addresses were located within residential areas and not in non-residential locations, such as rail yards or industrial areas.

Baseline characteristics of the prevalence of HIV, HCV and co-infections were compared using chi-square tests, and the statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Geographic autocorrelation analysis was conducted using ArcGIS version 10.2 (ESRI Inc., Redlands, California, USA), and geographic scan statistics were performed using SaTScan™ v9.1.1 software (Martin Kulldorff together with information Management Services Inc., Boston, USA).

Geographic autocorrelation analysis was applied to describe the correlation of a single variable between pairs of neighboring observations, with the standard measure of the Moran statistic. First, global spatial autocorrelation was used to explore the distribution of infections, in which all counties were seen as a whole [22]. The values of Moran’s I ranged from +1 (indicating strong autocorrelation) to 0 (indicating a random pattern) to −1 (indicating over-dispersion and uniformity). Second, Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA) was applied to identify significant spatial outliers and generate four geographic patterns, including high-high, high-low, low-high and low-low [14]. A high-high pattern indicated that a county and its surroundings collectively had a higher infection rate than the average. A low-low pattern showed that a county and its surroundings collectively had a lower infection rate than the average. A high-low pattern indicated that a county with an above-average infection rate was surrounded by counties with below-average infection rates. A low-high pattern showed that a county with a below-average infection rate was surrounded by counties with above-average infection rates.

Geographic scan statistics were applied to test for the presence and location of clusters. This analysis imposes a circular window of varying radii on the map surface and allows its center to move, so that at any given position and size, the window includes different sets of adjacent neighboring areas. As the window is placed at each neighborhood center, its radius varies continuously, from zero to a maximum radius that never exceeds 50% of the total study population. The method allows the circular window to continuously vary in both location and size, thereby creating a large number of distinct circular clusters. The significance of the identified clusters was tested with a likelihood ratio test against a null distribution obtained from Monte Carlo simulations [23]. Details of how the likelihood function is maximized over all windows under the Poisson assumption have been described elsewhere [24–26]. For the Monte Carlo inference, 999 replications were performed for ordinal or nominal variables, and 9999 replications were performed for dichotomous variables. After a cluster was identified, the strength of the clustering was estimated using the relative risk of infections within the cluster versus outside the cluster. The null hypothesis of no clusters was rejected when the P-value was less than or equal to 0.05.

Results

Study population

Approximately 31,015 clients with valid data for both demographic characteristics and HIV or HCV testing results from 2004 to 2014 were obtained from the database of the 72 MMT clinics in Guangxi. The majority of clients were males (90.39% of the sample), unemployed (55.22%), Han ethnic groups (67.26%), had a junior secondary school education (62.75%) and were living with family or relatives (79.75%). In total, 48.45% reported never having been married, 43.12% were married, and 8.33% were divorced, separated or widowed. Most of the clients obtained their living expenses in the past 6 months from family or friends (53.46%), followed by casual wages (26.01%) and fixed wages (4.51%). The remaining portion of the sample obtained their living expenses from social welfare, criminal activity or other means. In terms of drug use, the average age of initial drug use and length of drug use were 24.18 ± 6.64 years and 8.91 ± 5.03 years, respectively. The main drug currently injected was heroin (87.70%), and 68.28% used drugs by injection only. The average frequency of drug use was 3.06 ± 1.25 times per day in the past month, and 23.25% self-reported that they had shared needles with others. Of all MMT clients at baseline, 56.05% (17,383/31,015) had positive urine morphine testing results, 13.05% (4046/31,015) were infected with HIV (including the number of individuals who were infected with HIV only and those who were HIV/HCV co-infected), 72.51% (22,488/31,015) were infected with HCV (including the number of individuals who were infected with HCV only and those who were HIV/HCV co-infected), and 11.96% (3708/31,015) were HIV/HCV co-infected. There were significant differences in terms of demographic and behavioral characteristics among HIV, HCV, and HIV/HCV co-infected clients (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of MMT clients with HIV, HCV and co-infections in Guangxi (2004 ~ 2014)

| Characteristic | Total (n = 31,015) | HIV clients (n = 4046) | HCV clients (n = 22,488) | Co-infected clients (n = 3708) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of clients | Proportion (%) | No. of clients | Proportion (%) | No. of clients | Proportion (%) | No. of clients | Proportion (%) | |

| Gender | χ2 = 37.75, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 96.01, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 118.25, P < 0.001 | |||||

| Male | 28,036 | 90.39 | 3550 | 87.74 | 20,101 | 89.39 | 3249 | 87.62 |

| Female | 2979 | 9.61 | 496 | 12.26 | 2387 | 10.61 | 459 | 12.38 |

| Occupation | χ2 = 49.68, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 505.12, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 558.71, P < 0.001 | |||||

| Unemployed | 17,125 | 55.21 | 2415 | 59.69 | 13,143 | 58.44 | 2216 | 59.76 |

| Farmers | 9109 | 29.37 | 1135 | 28.05 | 5812 | 25.85 | 1034 | 27.89 |

| Others | 4781 | 15.42 | 496 | 12.26 | 3533 | 15.71 | 458 | 12.35 |

| Ethnic groups | χ2 = 111.43, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 419.45, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 472.78, P < 0.001 | |||||

| Han | 20,860 | 67.26 | 3004 | 74.24 | 15,876 | 70.60 | 2779 | 74.95 |

| Zhuang | 9399 | 30.30 | 990 | 24.47 | 6093 | 27.09 | 880 | 23.73 |

| Others | 756 | 2.44 | 52 | 1.29 | 519 | 2.31 | 49 | 1.32 |

| Marital status | χ2 = 144.04, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 141.98, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 242.64, P < 0.001 | |||||

| Married | 13,375 | 43.12 | 1426 | 35.25 | 9329 | 41.48 | 1305 | 35.19 |

| Unmarried | 15,055 | 48.54 | 2155 | 53.26 | 11,079 | 49.27 | 1972 | 53.18 |

| Others | 2585 | 8.34 | 465 | 11.49 | 2080 | 9.25 | 431 | 11.63 |

| Education | χ2 = 74.10, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 27.92, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 89.74, P < 0.001 | |||||

| Primary level education or below | 8274 | 26.68 | 1276 | 31.54 | 6129 | 27.25 | 1168 | 31.50 |

| Junior secondary school | 19,461 | 62.75 | 2446 | 60.45 | 13,911 | 61.86 | 2238 | 60.36 |

| Senior school or above | 3280 | 10.57 | 324 | 8.01 | 2448 | 10.89 | 302 | 8.14 |

| Living status | χ2 = 81.61, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 183.78, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 230.68, P < 0.001 | |||||

| With family or relatives | 24,734 | 79.75 | 3045 | 75.26 | 17,630 | 78.40 | 2796 | 75.40 |

| With friends | 971 | 3.13 | 108 | 2.67 | 644 | 2.86 | 96 | 2.59 |

| Alone | 2138 | 6.89 | 363 | 8.97 | 1623 | 7.22 | 321 | 8.66 |

| Others | 3172 | 10.23 | 530 | 13.10 | 2591 | 11.52 | 495 | 13.35 |

| Living expense source in the past six months | χ2 = 103.70, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 144.68, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 212.56, P < 0.001 | |||||

| From family or friends | 16,582 | 53.46 | 2257 | 55.78 | 11,950 | 53.14 | 2051 | 55.31 |

| From casual wages | 8067 | 26.01 | 877 | 21.68 | 5623 | 25.00 | 805 | 21.71 |

| From fixed wages | 1399 | 4.51 | 117 | 2.89 | 986 | 4.39 | 108 | 2.91 |

| Others | 4967 | 16.02 | 795 | 19.65 | 3929 | 17.47 | 744 | 20.07 |

| Age of initial drug use (years) | χ2 = 194.65, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 223.97, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 358.48, P < 0.001 | |||||

| < 24 | 17,372 | 56.01 | 2677 | 66.16 | 13,180 | 58.61 | 2476 | 66.77 |

| ≥ 24 | 13,643 | 43.99 | 1369 | 33.84 | 9308 | 41.39 | 1232 | 33.23 |

| Length of drug use at baseline (years) | χ2 = 1250.60, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 3413.13, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 4156.72, P < 0.001 | |||||

| < 5 | 9763 | 31.48 | 411 | 10.16 | 5011 | 22.28 | 340 | 9.17 |

| 5–10 | 7655 | 24.68 | 922 | 22.79 | 5846 | 26.00 | 852 | 22.98 |

| > 10 | 13,597 | 43.84 | 2713 | 67.05 | 11,631 | 51.72 | 2516 | 67.85 |

| Route of drug use in the past six months | χ2 = 674.72, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 6329.18, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 6595.77, P < 0.001 | |||||

| Injection intravenously only | 21,177 | 68.28 | 3446 | 85.17 | 18,015 | 80.11 | 3209 | 86.54 |

| Smoking or sniffing | 7957 | 25.66 | 382 | 9.44 | 3055 | 13.58 | 297 | 8.01 |

| Injection mixed with other | 1881 | 6.06 | 218 | 5.39 | 1418 | 6.31 | 202 | 5.45 |

| Receptive sharing of syringes with others | χ2 = 2840.14, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 1566.26, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 3753.07, P < 0.001 | |||||

| Yes | 7211 | 23.25 | 2276 | 56.25 | 6543 | 29.10 | 2137 | 57.63 |

| No | 23,804 | 76.75 | 1770 | 43.75 | 1,5945 | 70.90 | 1571 | 42.37 |

| Frequency of drug use in the past month | χ2 = 208.72, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 196.19, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 195.95, P < 0.001 | |||||

| 0 times/day | 2485 | 8.01 | 154 | 3.81 | 1615 | 7.18 | 143 | 3.86 |

| 1–3 times/day | 18,386 | 59.28 | 2278 | 56.30 | 13,147 | 58.46 | 2077 | 56.01 |

| 4–6 times/day | 8303 | 26.77 | 1289 | 31.86 | 6322 | 28.11 | 1220 | 32.90 |

| > 6 times/day | 1489 | 4.80 | 288 | 7.12 | 1188 | 5.29 | 245 | 6.61 |

| Missing | 352 | 1.14 | 37 | 0.91 | 216 | 0.96 | 23 | 0.62 |

| HIV status at baseline | – | χ2 = 855.02, P < 0.001 | – | |||||

| Positive | 4046 | 13.05 | 3708 | 16.49 | ||||

| Negative | 26,969 | 86.95 | 18,780 | 83.51 | ||||

| HCV status at baseline | χ2 = 855.02, P < 0.001 | – | – | |||||

| Positive | 22,488 | 72.51 | 3708 | 91.65 | ||||

| Negative | 8527 | 27.49 | 338 | 8.35 | ||||

| HIV/HCV co-infection at baseline | – | – | – | |||||

| Double positive | 3708 | 11.96 | ||||||

| Double negative | 8189 | 26.40 | ||||||

| Single positive and negative | 19,118 | 61.64 | ||||||

| Urine morphine testing results at baseline | χ2 = 24.79, P < 0.001 | χ2 = 13.21, P = 0.001 | χ2 = 33.50, P < 0.001 | |||||

| Positive | 17,383 | 56.05 | 2442 | 60.36 | 12,622 | 56.13 | 2190 | 59.06 |

| Negative | 13,085 | 42.19 | 1562 | 38.61 | 9507 | 42.28 | 1445 | 38.97 |

| Missing | 547 | 1.76 | 42 | 1.04 | 359 | 1.59 | 73 | 1.97 |

Of the 88 county-level areas in Guangxi, 63 locations were covered by MMT clinics, with the cumulative number of clients ranging from 45 to 2634. Clinics with more than a cumulative number of 400 clients were mostly distributed in the southern areas, with A county as the center. A county accounted for 41.55% of the total clients in these clinics (Fig. 2a). The residential addresses for all MMT clients were distributed throughout Guangxi in a pattern that was more closely clustered than random (Moran’s I = 0.14, P = 0.022).

Fig. 2.

Distribution, LISA cluster map and geographic scan clusters of HIV, HCV and co-infections of MMT clients from 2004 to 2014 in Guangxi. Red circles represent high risk clusters. a Distribution of all MMT clients; b Spatial clusters of HIV infection; c Spatial clusters of HCV infection; d Spatial clusters of HIV/HCV co-infection

Spatial clusters of HIV infection

The HIV infection rate of MMT clients was found to be strongly geographically clustered (Moran’s I = 0.33, P < 0.001). For high HIV infection rates, the results of LISA were similar to those of the geographic scan statistic (Fig. 2b and Table 2). LISA analysis identified three high-high locations distributed in B and C cities and D county and two high-low locations in A and E counties, which included 2844 MMT clients and 1041 HIV cases, with an HIV infection rate of 36.60% (1041/2844). Apart from these clusters, there were only 3005 HIV cases, with a 10.67% (3005/28,171) infection rate. The geographic scan statistic identified four significant high-risk clusters, which included 19 locations with a 23.73% (2264/9542) infection rate. The high-risk clusters were mainly concentrated in the northeastern parts where P county was the cluster center, along with the surrounding areas of E and F cities or A county alone. Apart from these clusters, there were only 1782 HIV cases with an 8.30% (1782/21,473) infection rate. For low HIV infection rates, the geographic scan statistic identified three significant low-risk clusters, which included 19 locations with a 3.66% (334/9131) infection rate. These low-risk areas were mainly distributed in the northwestern parts, where H city was the cluster center, or in the southern parts, where I county and J city were the cluster centers. LISA analysis showed that there were no significant low-low locations for HIV infection rates.

Table 2.

General description of the clusters with high and low prevalence of HIV, HCV and co-infections among MMT clients in Guangxi (2004 ~ 2014)

| Type of infection | Type of cluster | No. of counties/cities | Radius (km2) | MMT clients | No. of infections | Relative risk | Log likelihood ratio | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV infection | High risk cluster | 14 | 11.95 | 7074 | 1405 | 1.80 | 147.72 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 6.24 | 627 | 220 | 2.79 | 81.90 | <0.001 | ||

| 2 | 6.14 | 708 | 173 | 1.91 | 28.76 | <0.001 | ||

| 1 | 0.00 | 1133 | 466 | 3.43 | 230.27 | <0.001 | ||

| Low risk cluster | 7 | 11.23 | 2556 | 74 | 0.21 | 156.90 | <0.001 | |

| 7 | 8.91 | 4209 | 144 | 0.24 | 234.95 | <0.001 | ||

| 5 | 9.29 | 2366 | 116 | 0.36 | 84.01 | <0.001 | ||

| HCV infection | High risk cluster | 14 | 11.95 | 7074 | 5626 | 1.13 | 30.50 | <0.001 |

| 8 | 9.48 | 6692 | 5655 | 1.22 | 81.59 | <0.001 | ||

| Low risk cluster | 12 | 12.01 | 4224 | 2392 | 0.75 | 90.92 | <0.001 | |

| 4 | 7.61 | 1142 | 684 | 0.82 | 13.80 | 0.002 | ||

| 1 | 0.00 | 680 | 381 | 0.77 | 14.11 | 0.008 | ||

| 1 | 0.00 | 342 | 5 | 0.02 | 224.78 | <0.001 | ||

| HIV/HCV co-infection | High risk cluster | 13 | 10.95 | 4888 | 1008 | 2.00 | 156.03 | <0.001 |

| 2 | 6.24 | 627 | 201 | 2.78 | 74.43 | <0.001 | ||

| 2 | 6.14 | 708 | 160 | 1.93 | 27.31 | <0.001 | ||

| 1 | 0.00 | 1133 | 466 | 3.43 | 230.27 | <0.001 | ||

| Low risk cluster | 7 | 8.91 | 4209 | 129 | 0.23 | 219.66 | <0.001 | |

| 7 | 11.32 | 2556 | 68 | 0.21 | 143.51 | <0.001 | ||

| 5 | 9.29 | 2366 | 102 | 0.34 | 81.52 | <0.001 | ||

| 1 | 0.00 | 342 | 0 | 0.00 | 25.11 | <0.001 |

Spatial clusters of HCV infection

Significant spatial clustering was detected for the HCV infection of MMT clients (Moran’s I = 0.41, P < 0.001). For high HCV infection rates, LISA analysis observed two high-high locations distributed in M and N cities and one high-low location in F city, which included 3490 MMT clients and 3105 HCV cases, with an HCV infection rate of 88.97% (3105/3490). Apart from these clusters, there were only 19,383 HCV cases, with a 70.72% (19,383/27,525) infection rate. The geographic scan statistic identified two significant high-risk clusters, which included 22 locations with an 81.95% (11,281/13,766) infection rate. One cluster included eight locations distributed in southern areas where M city was the cluster center, and the other cluster included 14 locations distributed in the northeastern parts where P county was the cluster center. Apart from these clusters, there were only 11,207 HCV cases, with a 64.97% (11,207/17,249) infection rate. For low HCV infection rates, LISA analysis observed three low-low locations distributed in X, Y, and Z counties and one low-high location in Q county, with a 29.42% (373/1268) infection rate. The geographic scan statistic identified four significant low-risk clusters, which included 18 locations with a 54.20% (3462/6388) infection rate. These low-risk areas were mainly located in western parts, where T county was the cluster center, and in the central parts, where L city was the cluster center, along with sporadic counties, such as I and Q counties (Fig. 2c and Table 2).

Spatial clusters of HIV/HCV co-infection

The co-infection rate of HIV/HCV among MMT clients was more closely clustered than resembling a random pattern (Moran’s I = 0.30, P = 0.003). The clustering pattern was closely similar to that of the HIV infection rate (Fig. 2d and Table 2). Except for Q county, the clustering areas for co-infection rates detected by the geographic scan statistic were identical with those of LISA analysis. The geographic scan statistic identified four significant high-risk clusters, with a 24.95% (1835/7356) co-infection rate of 18 locations, and four significant low-risk clusters, with a 3.16% (299/9473) co-infection rate of 20 locations.

Co-clustering of HIV, HCV and co-infections

As shown in Fig. 3, many significant clusters of HIV, HCV, or co-infections overlapped. For the significant high-risk clusters, the overlaps for these infections were located in the northeastern parts where P county was the cluster center, which covered 13 locations where the radius was 10.95 km2. In addition, the overlaps for HIV and co-infections were also located in the surrounding areas where E and F cities were the cluster centers, as well as A county (Fig. 3a). For the significant low-risk clusters, the overlap for HIV, HCV and co-infections was only I county, while the overlaps for HIV and co-infections were also located in the surrounding areas where H and J cities were the cluster centers, and the overlap for HCV and co-infections also contained Q county (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Co-clustering of HIV, HCV and co-infections among MMT clients from 2004 to 2014 in Guangxi. Red circles represent high risk clusters, blue circles represent low risk clusters. a High risk clusters; b Low risk clusters

Spatial clusters of epidemic factors

Significant spatial clustering was also detected for several of demographic and behavioral factors, and most of them were likely to reside within the clusters of HIV, HCV, or co-infections (Fig. 4 and Table 3). Of the demographic factors, only being unmarried and having a primary level education or below were geographically clustered. Of risky injection practices, injectors who reported more than 10 years of drug use and receptive sharing of syringes with others were geographically clustered. As shown in Fig. 4, the high-risk clusters for these significant clustering characteristics were mainly located within or surrounding the northeastern parts where P county was the cluster center. In addition, two characteristics of injection practices were also located near one of the overlaps for HIV and co-infections (such as the surrounding areas where E city was the cluster center) or one of the high-risk clusters of HCV infection (such as the southern parts where M city was the cluster center). For the low-risk clusters, most of them were distributed in the western and southeastern parts, which are located near one of the low-risk clusters for HIV, HCV, or co-infections.

Fig. 4.

Distribution and significant spatial clustering of demographic and behavioral variables. a Being unmarried; b Primary level of education or below; c Having used drugs more than 10 years; d Receptive syringe sharing with others

Table 3.

Significant high risk clusters of demographic and behavioral characteristics of MMT clients in Guangxi

| Characteristic | Moran’s I ± SD expected I = −0.0161 | P value for clustering | No. of counties/cities | Radius (km2) | Relative risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Being unmarried | 0.2002 ± 0.0024 | <0.001 | 5 | 7.50 | 1.38 |

| 3 | 6.77 | 1.21 | |||

| Primary level education or below | 0.1167 ± 0.0024 | 0.007 | 4 | 7.40 | 1.43 |

| 2 | 6.77 | 1.48 | |||

| Having used drugs for more than 10 years | 0.0979 ± 0.0024 | 0.020 | 3 | 7.93 | 1.63 |

| 3 | 7.56 | 1.69 | |||

| Receptive sharing of syringes with others | 0.1091 ± 0.0024 | 0.010 | 6 | 8.03 | 1.62 |

| 4 | 7.73 | 1.34 | |||

| 3 | 7.34 | 1.74 | |||

| 1 | 0.00 | 1.99 |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the spatial distribution patterns of HIV and HCV epidemics in relation to MMT clients and their possible interactions in Guangxi. The overall infection rates of HIV, HCV, and HIV/HCV among MMT clients at treatment baseline were 13.05%, 72.51% and 11.96% respectively, which were similar to the rates of high-transmission areas (including Yunnan, Guizhou, Sichuan and Xinjiang) of China, but distinctly higher than those of the other provinces [8]. This finding indicated that the rates of these infections remained highly concentrated among provinces along the traditional drug-trafficking routes, and MMT clinics have recruited more HIV- or HCV-infected drug users as a result of the 2006 national policy to relax the eligibility criteria for MMT enrollment. The similar infection rates of HIV and HIV/HCV suggest that HIV-infected MMT clients were at high risk of co-infected HCV infection. Additionally, this finding showed the important role of IDUs in driving the HCV epidemic among PWID and HIV-infected individuals, which was consistent with previously published evidence [3, 6, 27].

Our study demonstrated that HIV, HCV and co-infections in Guangxi all exhibited significant geographic clustering at the county level, and their distribution patterns overlapped to some degree, particularly for HIV and HIV/HCV co-infection. The most significant high-risk overlapping clusters for these infections surrounded P county in the northeastern area of Guangxi. The overlaps for HIV and co-infections were also located in the area surrounding E and F cities in the southwestern areas of Guangxi, as well as A county. Several important points are considered in interpreting the geographic distribution patterns of these infections. First, E city is adjacent to Vietnam, where the HIV epidemic was driven by IDUs in the early phase and formed the spreading trends from the South to the North since 1990. Guangxi thus first detected a domestic HIV-1 case among IDUs in one county of E city in 1996, which gradually led to an HIV outbreak among drug users in the surrounding border areas [9, 28, 29]. Second, because of its shared border with the ‘Golden Triangle’ and Yunnan province, which were the earliest and most severe HIV/AIDS epidemic areas in China, F city became one of the most severely affected HIV/AIDS areas initially fueled by IDUs in Guangxi [30]. Third, as previous studies have shown, the geographic concentrations of HIV in poor and underserved areas and the dispersion of HIV along roads and highways [31–34] are high, and it is indeed the case that most of the locations surrounding P county, including E and F cities, belong to economically depressed areas. These findings corroborated that HIV and HCV epidemics first broke out within the border areas adjacent to the ‘Golden Triangle’ and then along drug trafficking routes to other parts of Guangxi, and poverty might play an important role in accelerating these epidemics. Meanwhile, the most significant low-risk overlapping clusters for HIV, HCV or co-infections were mainly located in areas surrounding H and J cities or I county, which was consistent with the trend from routine monitoring data of Guangxi. This information suggested that some behavioral or biological protective factors appear to have slowed the transmission of these infections in the low-risk clusters.

The distribution patterns of HIV, HCV and co-infections are similar to those across different counties, which might be attributed to the similarities in the features of the epidemics. Compared with related studies [35–37], our findings showed that several epidemic factors, such as being unmarried, having a primary level of education or below, having used drugs for more than 10 years and receptive sharing of syringes with others, were geographically clustered. Most of the individuals with these factors were more likely to reside in one of clusters for HIV, HCV and co-infections, especially for the high-risk clusters (e.g., the areas surrounding P county as the cluster center). Numerous studies have reported that the emergence of MMT and other harm reduction programs have resulted in lower levels of risky behaviors and reductions in the HIV epidemic [7, 12, 38, 39]. However, not all previous studies have found such a tight linkage, as one study from the San Francisco Bay Area [40] found that risky injection practices were indeed lower among drug users from poorer communities targeting harm reduction programs, but the prevalence of HIV remained high. Therefore, additional studies should be conducted to evaluate the spatial distribution of these infections and their association with epidemic features after MMT programs have been more widely established.

The similar prevalence and overlapping spatial clusters found in our study between HIV and HIV/HCV co-infection suggest a higher prevalence of HCV co-infection among HIV-infected PWID in Guangxi. Co-infection of HIV and HCV interact synergistically by affecting the transmission history and reducing the immune clearance of the other. Individuals co-infected with HCV could boost the occurrence of HIV infection, with the perinatal transmission risk doubling in HIV-infected mothers [41, 42], thus altering immunological responses to antiretroviral therapy and accelerating the risk of drug-related hepatotoxicity and consequently cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma [43–45]. Meanwhile, HIV-infected individuals without treatment are less likely to spontaneously clear HCV infection; they may then experience more rapid HCV disease progression than HIV-negative individuals [3, 46]. Given the fact that a large proportion of HIV cases are acquired through IDUs in Guangxi, there is an urgent need to comply with international guidelines that recommend HCV screening for HIV-infected individuals, investment in building HCV surveillance and care, and access to direct-acting antiviral treatment for those with chronic active infection [47–50]. Comprehensive measures in parallel to MMT, such as antiretroviral therapy, 100% use of condoms, needle exchanges and sexually transmitted disease management services should be promoted as well.

Several limitations in this study should be noted. First, it is difficult to determine whether the distribution patterns and associations of the MMT clients described in this report are true for the entire population of injectors in this region. However, one study reported by national sentinel surveillance has shown that the national HIV prevalence among MMT clients was not significantly different from that of non-MMT drug users from 2004 to 2009 [8]. Second, most of the data included were obtained from 2008 to 2014, given that a national MMT program database was developed in 2004 to monitor the pilot and was later upgraded to a web-based management database in 2008. Third, most of the data, including residential addresses and drug use behaviors, were self-reported, and we have no way knowing the proportion of the clients giving false or misleading information. Nevertheless, the information bias might be narrowed given that the staff members of local MMT clinics needed to receive a series of professional trainings on assessment surveys, after which they could upload clients’ information to the national web-based management database prior to their assignment. Most of the clients were later contacted at the addresses they provided as well. Finally, MMT clients without a fixed address (and who were thus more likely to be at high risk) were excluded, and drug use is likely to occur in venues or areas of the city that might not coincide with an address. Therefore, the location of consumption would have been a better approach for the analysis.

Conclusions

Using spatial analysis for detecting the HIV and HCV epidemics among drug users from a cohort study of MMT programs from 2004 to 2014, we revealed two important findings. First, HIV, HCV and co-infections among MMT clients in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region all presented substantial geographic heterogeneity at the county level with a number of overlapping significant clusters. Second, areas surrounding P county were effective in enrolling high-risk clients in their MMT programs, which in turn might allow PWID to inject less, share fewer syringes, and receive referrals for HIV or HCV treatment in a timely manner.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank staff members who have been involved in the surveillance, laboratory testing and treatment of HIV/AIDS patients in Guangxi.

Funding

The study was supported by grants from the Guangxi Bagui Honor Scholars, Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2012ZX10001–002).

Availability of data and materials

The data of HIV and HCV epidemics, incorporating demographic information of MMT clients in Guangxi were obtained from Guangxi Center for Disease Prevention and Control (http://10.249.1.170/).

Abbreviations

- AIDS

Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

- ASEAN

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations

- CDC

Center for Disease Control and Prevention

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay

- GIS

Geographical information system

- HCV

Hepatitis C virus

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IDUs

Injecting drug users

- LISA

Indicators of Spatial Association

- MMT

Methadone maintenance treatment

- PWID

People who inject drugs

- SPSS

The SPSS Statistical Package for Social Sciences

Authors’ contributions

GHL, MLL and RJL conceived and designed the study. MLL, CYL, NXL, HBH, ZRP, CWH, FZ and XYT conducted data processing and statistical analysis. MLL and RJL wrote the manuscript. GHL revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all clients. Ethical approval for the MMT was granted by the institutional review board of the National Center for AIDS/STD Control and Prevention, China CDC.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mingli Li, Email: limingligx@126.com.

Rongjian Li, Email: 532101781@qq.com.

Zhiyong Shen, Email: Shenzhiyong99999@sina.com.

Chunying Li, Email: 421093246@qq.com.

Nengxiu Liang, Email: 276815093@qq.com.

Zhenren Peng, Email: 275712677@qq.com.

Wenbo Huang, Email: 389907937@qq.com.

Chongwei He, Email: 850975621@qq.com.

Feng Zhong, Email: 56699928@qq.com.

Xianyan Tang, Email: 1760643593@qq.com.

Guanghua Lan, Phone: 86-771-2518724, Email: ghlangx@163.com.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. How AIDS changes everything-MDG 6: 15 lessons of hope from the AIDS response. Geneva: the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS; 2015.

- 2.Gower E, Estes C, Blach S, Razavi-Shearer K, Razavi H. Global epidemiology and genotype distribution of the hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol. 2014;61(Suppl1):S45–S57. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Platt L, Easterbrook P, Gower E, et al. Prevalence and burden of HCV co-infection in people living with HIV: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16(7):797–808. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00485-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNAIDS . A joint assessment of HIV/AIDS prevention, treatment and care in China (2004) China Ministry of Health: Beijing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNAIDS . China’s Titanic Peril: 2001 Update of the AIDS Situation and Needs Assessment Report. China Ministry of Health: Beijing; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nelson PK, Mathers BM, Cowie B, et al. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B and hepatitis C in people who inject drugs: results of systematic reviews. Lancet. 2011;378(9791):571–583. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61097-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yin W, Hao Y, Sun X, et al. Scaling up the national methadone maintenance treatment program in China: achievements and challenges. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(Suppl 2):ii29–ii37. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhuang X, Liang Y, Chow EP, et al. HIV and HCV prevalence among entrants to methadone maintenance treatment clinics in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:130. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guangxi Public Health Department . Annual Report on Provincial AIDS/STD in 2004. Guangxi: Guangxi Public Health Department; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guangxi Public Health Department . Annual Report on Provincial AIDS/STD Surveillance in 2003. Guangxi: Guangxi Public Health Department; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li ML, Zhu QY, Zheng WB, et al. A retrospective cohort study on the mortality of AIDS patients in Guangxi, China (2001-2011) AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2015;31(4):439–447. doi: 10.1089/aid.2014.0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pang L, Hao Y, Mi G, et al. Effectiveness of first eight methadone maintenance treatment clinics in China. AIDS. 2007;21(Suppl 8):S103–S107. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000304704.71917.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu W, Hu Y, Yu S, et al. Temporal-spatial clustering and socio-economic influencing factors of hepatitis C in mainland China, 2008-2013. Chin J Public Health. 2016;32(4):482–487. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhou YB, Liang S, Wang QX, et al. The geographic distribution patterns of HIV-, HCV- and co-infections among drug users in a national methadone maintenance treatment program in Southwest China. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xing J, Jia M, Wang L, et al. Study on the temporal-spatial analysis of HIV infection among injecting drug users in Yunnan Province from 2004 to 2011. Chin J Dis Control Prev. 2014;18(4):317–321. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng Z, Yang H, Cheng Y, et al. Study on the spatial distribution of AIDS based on geographic information system in Jiangsu province. Chin J Epidemiol. 2011;32(1):42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang Z, Yin W, Huang Y, et al. A survey of HIV, HCV, syphilis and HSV-2 among drug users attending methadone maintenance clinics in Guangxi and Guizhou. Chin J AIDS STD. 2010;16(05):470–472. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bai Y, Lai W, Wei L. Prevalence of HIV, HCV and Syphilis Infection at Methadone Maintenance Treatment Clinic in Liuzhou City. J Prev Med Inf. 2009;25(11):910–912. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan Y, Wei QH, Chen LJ, et al. Molecular epidemiology of HCV monoinfection and HIV/HCV coinfection in injection drug users in Liuzhou, Southern China. PLoS One. 2008;3(10):e3608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han M, Chen Q, Hao Y, et al. Design and implementation of a China comprehensive AIDS response programme (China CARES), 2003-08. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(Suppl 2):ii47–ii55. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Du WJ, Xiang YT, Wang ZM, et al. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of 3129 heroin users in the first methadone maintenance treatment clinic in China. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;94(1–3):158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moran PA. Notes on continuous stochastic phenomena. Biometrika. 1950;37(1–2):17–23. doi: 10.1093/biomet/37.1-2.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Assuncao RM, Reis EA. A new proposal to adjust Moran's I for population density. Stat Med. 1999;18(16):2147–2162. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19990830)18:16<2147::AID-SIM179>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kulldorff M, Feuer EJ, Miller BA, et al. Breast cancer clusters in the northeast United States: a geographic analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146(2):161–170. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulldorff M, Nagarwalla N. Spatial disease clusters: detection and inference. Stat Med. 1995;14(8):799–810. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780140809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kulldorff M. A spatial scan statistic. Communications in StatisticsTheory and Methods. 1997;26:1481–1496. doi: 10.1080/03610929708831995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulldorff M. Information Management Services, Inc: SaTScan™ v6.0: Softwarefor the spatial and space-time scan statistics. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wiessing L, Ferri M, Grady B, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection epidemiology among people who inject drugs in Europe: a systematic review of data for scaling up treatment and prevention. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e103345. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nerurkar VR, Nguyen HT, Dashwood WM, et al. HIV type 1 subtype E in commercial sex workers and injection drug users in southern Vietnam. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1996;12(9):841–843. doi: 10.1089/aid.1996.12.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen J, Liang F, Liang S, et al. An investigation on HIV infection among drug users at Pingxiang city in Guangxi province, southern China. J Chin AIDS/STD Prev Cont. 1998;4(3):97–100. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang G, Zheng X, Liu W, et al. The survey of HIV prevalence among drug users in Guangxi, China. Chin J Epidemiol. 2000;21(1):15–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pellowski JA, Kalichman SC, Matthews KA, et al. A pandemic of the poor: social disadvantage and the U.S. HIV epidemic. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):197–209. doi: 10.1037/a0032694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baral S, Logie CH, Grosso A, et al. Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:482. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson FE, et al. Social context of sexual relationships among rural African Americans. Sex Transm Dis. 2001;28(2):69–76. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200102000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallace RG. AIDS in the HAART era: New York's heterogeneous geography. Soc Sci Med. 2003;56(6):1155–1171. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00121-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heimer R, Barbour R, Shaboltas AV, et al. Spatial distribution of HIV prevalence and incidence among injection drugs users in St Petersburg: implications for HIV transmission. AIDS. 2008;22(1):123–130. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f244ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qian S, Guo W, Xing J, et al. Diversity of HIV/AIDS epidemic in China: a result from hierarchical clustering analysis and spatial autocorrelation analysis. AIDS. 2014;28(12):1805–1813. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou Y, Liang S, Pan P, et al. The geographic distribution patterns of HIV-,HCV- and co-infections among drug users in a national methadone maintenance treatment program in Southwest China. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:134. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duan S, Yang Y, Han J, et al. Study on incidence of HIV infection among heroin addicts receiving methadone maintenancetreatment in Dehong prefecture, Yunnan province. Chin J Epidemiol. 2011;32(12):1227–1231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westercamp N, Moses S, Agot K, et al. Spatial distribution and cluster analysis of sexual risk behaviors reported by young men in Kisumu, Kenya. Int J Health Geogr. 2010;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joseph H, Stancliff S, Langrod J. Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT): a review of historical and clinical issues. Mt Sinai J Med. 2000;67(5–6):347–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sulkowski MS. Viral hepatitis and HIV coinfection. J Hepatol. 2008;48(2):353–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Valle Tovo C, Alves de Mattos A, Ribeiro de Souza A, et al. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus infection in patients infected with the hepatitis C virus. Liver Int. 2007;27(1):40–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2006.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shepard CW, Finelli L, Alter MJ. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5(9):558–567. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70216-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stebbing J, Waters L, Mandalia S, et al. Hepatitis C virus infection in HIV type 1-infected individuals does not accelerate a decrease in the CD4+ cell count but does increase the likelihood of AIDS-defining events. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(6):906–911. doi: 10.1086/432885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greub G, Ledergerber B, Battegay M, et al. Clinical progression, survival, and immune recovery during antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus coinfection: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Lancet. 2000;356(9244):1800–1805. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas DL, Astemborski J, Rai RM, et al. The natural history of hepatitis C virus infection: host, viral, and environmental factors. JAMA. 2000;284(4):450–456. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.WTO. Guidelines for the screening,treatment and care for persons with hepatitis C. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. [PubMed]

- 49.European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2014. J Hepatol. 2014;61(2):373–95. http://files.easl.eu/easl-recommendations-on-treatment-of-hepatitis-C.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 50.Soriano V, Puoti M, Sulkowski M, et al. Care of patients coinfected with HIV and hepatitis C virus: 2007 updated recommendations from the HCV-HIV International Panel. AIDS. 2007;21(9):1073–1089. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3281084e4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data of HIV and HCV epidemics, incorporating demographic information of MMT clients in Guangxi were obtained from Guangxi Center for Disease Prevention and Control (http://10.249.1.170/).