Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS

Sjögren’s syndrome and autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) are disorders with decreased function of salivary, lacrimal glands, and the exocrine pancreas. NOD/ShiLTJ mice and mice transduced with the cytokine BMP6 develop Sjögren’s syndrome and chronic pancreatitis and MRL/Mp mice are models of AIP. CFTR is a ductal Cl− channel essential for ductal fluid and HCO3− secretion. We used these models to ask: is CFTR expression altered in these diseases, does correction of CFTR correct gland function, and most notably, does correcting ductal function correct acinar function.

Methods

We treated the mice models with the CFTR corrector C18 and the potentiator VX770. Glandular, ductal and acinar cells damage, infiltration of immune cells, and function were measured in vivo and in isolated duct/acini.

Results

In the disease models, CFTR expression is markedly reduced. The salivary glands and pancreas are inflamed with increased fibrosis and tissue damage. Treatment with VX770 and, in particular C18 restored salivation, rescued CFTR expression and localization, nearly eliminated the inflammation and tissue damage. Transgenic over-expression of CFTR exclusively in the duct had similar effects. Most notably, the markedly reduced acinar cell Ca2+ signaling, Orai1, IP3 receptors, AQP5 expression and fluid secretion were restored by rescuing ductal CFTR.

Conclusions

Our findings reveal that correcting ductal function is sufficient to rescue acinar cell function and suggests that CFTR correctors are strong candidates for the treatment of Sjögren’s syndrome and pancreatitis.

Keywords: Pancreatitis, Sjögren’s syndrome, duct, CFTR

Introduction

Fluid and electrolyte secretion to the luminal space is the cardinal function of secretory glands, like the salivary glands and the pancreas. The secreted fluid washes the macromolecules secreted by the acini to their destination, the oral cavity and the intestine. Fluid and electrolyte secretion occurs in two steps1. The acinar cells secrete isotonic NaCl-rich fluid2, and the ducts modify the composition and the volume of the fluid1. The salivary glands duct absorbs both the Na+ and Cl− and secretes K+ and HCO3−3, while the pancreatic duct absorbs the Cl− and secretes HCO3−, resulting in highly alkaline fluids1.

Aberrant fluid secretion is observed in many secretory gland diseases, including cystic fibrosis (CF), acute and chronic pancreatitis and Sjögren’s syndrome1. CF is caused by mutations in the Cl− channel CF transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR)4. The most common causes of pancreatitis are alcohol consumption, duct obstruction, autoimmune attack and hereditary causes5. Sjögren’s syndrome is chronic autoimmune disease that affects the salivary and lacrimal glands, resulting in xerostomia and dry eye6. These diseases are inflammatory, with infiltration of inflammatory cells that tend to form foci around ducts7. The inflammation gradually destroys the parenchyma that is replaced by connective tissue.

Since in secretory gland diseases the function of acinar cells is compromised8, 9 and in the case of pancreatitis a major cause of the disease is activation of digestive enzymes and cathepsin B within the acinar cells10, until recently most studies to understand and develop treatment for these diseases focused on acinar cells. However, in recent years our work3 and that of others11 emphasized the importance of the duct in secretory gland diseases. An established link between ductal function and secretory gland diseases is CF, in which compromised ductal function results in pancreatic insufficiency12. Moreover, pancreatic insufficiency correlates with mutations in CFTR that affect HCO3− transport13 and mutations in CFTR that cause chronic pancreatitis without causing CF14 were recently found to specifically modify CFTR HCO3− permeability15. A notable finding is that CFTR is mislocalized in the duct of AIP, alcoholic and idiopathic pancreatitis patients16, 17. Importantly, treatment of AIP patients with corticosteroids restored CFTR ductal localization, increased pancreatic HCO3− secretion and improved the function of the pancreas16.

The state of CFTR in animal models of Sjögren’s syndrome and pancreatitis is not known. There is sparse evidence that altered CFTR may play a role in Sjögren’s syndrome, although this disease is considered to mainly affect acinar cells. Thus, HCO3− secretion is reduced in Sjögren’s syndrome1. One study reported reduced expression of CFTR in rabbit lacrimal gland Sjögren’s syndrome model, although analysis of CFTR protein was not rigorous18. A recent study reported that acute application of CFTR channel activators to the eye surface increased tear secretion in wild-type mice and mice with ablation of the lacrimal glands19. However, the state of CFTR in the glands and how ductal CFTR function affect the function of serous cells is not known.

The association between secretory gland diseases and aberrant ductal and CFTR functions raised the prospect of improving CFTR function as a treatment for Sjögren’s syndrome, chronic pancreatitis and perhaps other secretory diseases. A key question in this respect is whether correcting ductal function also corrects acinar cells function. The development of CFTR potentiators and correctors20, 21 that are in clinical use to treat CF22, 23 allowed to address these questions. CFTR potentiators increase channel activity of CFTR. CFTR correctors facilitate targeting of misfolded CFTR to the plasma membrane and reduce their degradation.

In the present studies, we examined the effect of the CFTR corrector C18 and potentiator VX770 in Sjögren’s syndrome and AIP models. We used NOD/ShiLTJ and MRL/Mp and MRL/MpJ-Faslpr (MRL/Mp-Fas) mice that develop Sjögren’s syndrome-like and AIP-like phenotypes 24–27 and mice with salivary glands expressing BMP6 develop a Sjögren’s syndrome-like disease28. In the models CFTR level is markedly reduced and the remaining CFTR is mislocalized and the glands were inflamed and damaged. VX-770 and C18 reversed the disease phenotype and improved ductal fluid secretion. Salivation nearly recovered to WT levels and remained so until treatment was stopped. Treatment with VX770 had no major effect on CFTR expression, while treatment with C18 fully restored CFTR expression and localization. Treatment with C18 decreased the inflammation, inflammatory cells infiltration, fibrosis and tissue damage. Transgenic expression of CFTR exclusively in the duct had similar effects. In NOD/ShiLTJ mice with established salivary gland dysfunction, salivary gland acinar cell ER Ca2+ release, Ca2+ influx, expression of IP3Rs, Orai1, and AQP5 are markedly reduced. Yet, remarkably, restoring ductal CFTR function increased acinar cells AQP5 expression, Ca2+ signaling, and fluid secretion. Pharmacological rescue of CFTR also restored Ca2+ signaling and fluid secretion in pancreatic acinar cells of NOD/ShiLTJ and MRL/Mp mice. These findings are the first to show that restoring ductal function is sufficient to restore acinar cell function in exocrine gland diseases and suggests that the FDA approved CFTR correctors are strong candidates for the treatment of Sjögren’s syndrome and pancreatitis.

Methods

Animals

Eight-week old non-obese diabetic (NOD), FVB/nj (WT), MRL/Mp and MRL/MpJ-Faslpr (referred to as MRL/Mp-Fas all along) female mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. All protocols used with the mice have been approved by the NIH animal use committee (ASP 16-799). The NOD mice were housed under controlled temperature and 12 hrs dark/light cycles with free access to water and food. Twelve weeks old female MRL/Mp and part of the MRL/Mp-Fas mice were treated with Poly IC exactly as described27 to induce AIP. Treatment with C18 started one month after start of treatment with Poly IC that continued during the two weeks treatment with C18. Twelve weeks old NOD mice were treated with VX770 (Sigma) or C18 (1-(benzo[d][1,3]dioxol-5-yl)-N-(5-((S)-(2-chlorophenyl)((R)-3-hydroxypyrrolidin-1-yl)methyl)thiazol-2-yl)cyclopropanecarboxamide). C18 was obtained from the CFFT modulator panel distributed by Rosalind Franklin University. C18 was synthesized by Exclusive Chemistry LTD (Obninski, Russia) as in Vertex patent WO2007/021982A2. Treatment with C18 and VX770 was by daily I.P. injection of 2 mg/kg dissolved in DMSO in a volume of 50 μl. At the end of treatments mice were sacrificed and the pancreas, parotid, and submandibular glands were removed for analysis.

Isolation and culturing of parotid and pancreas duct

Cultured, sealed parotid and pancreatic ducts were prepared as described previously29. Briefly, the mice parotid glands and pancreas were removed and injected with a digestion buffer containing DMEM, STI, BSA, hyaluronidase and collagenase. Intralobular ducts were micro-dissected and were maintained in primary culture for 24–36 hrs before use. Sealed ducts were selected and equilibrated in HEPES-buffered solution A (in mM) 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES (pH 7.4), 10 Glucose) to establish the resting state. The ducts were then perfused with a HCO3−-buffered solution (in mM) 120 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 2.5 HEPES (pH 7.4), 10 Glucose, 25 Na+-HCO3− equilibrated with 5% CO2). The ducts were stimulated by including 5 μM Forskolin in the perfusate. Ductal fluid secretion was analyzed by video microscopy as described before30.

Histopathology

Submandibular and parotid glands and the pancreas were removed and embedded in OCT compound. The pancreas was cut approximately in half to yield a head and a tail samples. Then sections (6 μm thick each) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and Trichrome. An infiltration focus was defined as an aggregate of 50 or more mononuclear inflammatory cells. Foci were determined through the whole section in a total of four sections per gland using 20x magnification, each group containing 3–4 mice. The results were calculated and expressed as number of infiltrates foci per section. Infiltrated area was calculated in whole sections using the Metamorph software. Infiltration in the pancreas was determined according to31 on 0–4 scale from no to severe damage.

Immunofluorescence

The tissue sections were blocked with 20% donkey serum (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and treated with the required primary antibody, rabbit anti-AQP5 (Alomone), rabbit anti-CFTR (Cell Signaling Technology, CST), monoclonal anti- IP3R3 (BD Transduction Laboratories), anti-CD3, anti-C68 and anti-B200 antibodies and the required secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Anti-Orai1 antibodies were raised in rabbit and purified using the peptide used to generate the antibodies. Samples were mounted with DAPI (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and imaged with Olympus confocal microscope.

Measurement of [Ca2+]i

Acini attached to poly-L-lysine were loaded with Fura2 by incubation with 5 μM Fura2/AM at 37°C for 15 min and were continuously perfused with a warm, 37°C solution A, solution A containing 2 or 5 mM Ca Cl2 or Ca2+-free solution A containing 0.2 mM EGTA, as indicated in the Figures. Agonists were added to the perfusate. Fluorescence was recorded at excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm, and emitted light at wavelength higher than 510 nm was collected. Images were collected every 2 seconds and analyzed with MetaFluor software. Results are presented as the normalized change in 340/380 ratio.

Measurement of Cell Volume

Acini were loaded by incubation with 1uM Calcein/AM (ANASPEC) dissolved in solution A for 10 min at room temperature. Acini were continuously perfused and fluorescence was recorded every 2 seconds at excitation wavelengths of 490 nm, and emitted light at wavelength higher than 510 nm was collected. Images were analyzed with MetaFluor software. At the end of each experiment the signals were calibrated by exposing the cells to a solution of 20% reduced osmolarity and the signal was taken as 20% change in cell volume.

Transduction of CFTR and BMP6

The Ad5/GFP-CFTR vector was a generous gift from Dr. Chang, University of Arizona32 and was used at 9.4×1010 particles/gland in 100ul. AAV5-Bmp6 vector was described previously28 and was used at AAV5-GFP or AAV5-BMP6 5×1010 particles/gland in 100ul. The vectors were infused through the opening of the SMG duct to the oral cavity as detailed before33. The GFP-CFTR and GFP vectors were delivered into the submandibular gland of 12 weeks old NOD and FVB/nj mice, transduced mice were used for experiments 7–10 days after transduction. The BMP6 transduced mice were used 6 months after transduction.

Statistics

Results are expressed as mean±s.e.m of the indicated number of independent experiments and mice and the number of ducts/acinar cells analyzed. Statistical significance was determined by students t-test or analysis of variance, as appropriate.

Results

Treatment with C18 and VX-770 restores salivation in NOD mice

Salivary secretion by NOD/ShiLTJ mice is a model of Sjögren’s syndrome24. In supplementary Figure S1, we confirmed reduced salivation by these mice and show the time course in response to cholinergic stimulation with pilocarpine before treatment. The same mice were treated for 12 days by daily I.P. injection with 2 mg/kg of the corrector C18 (Figure S1a, b) or the potentiator VX-770 (Figure S1c). The VX-770 dose is about half the dose used with humans when taken orally22. Preliminary experiments showed no effect of VX-770 or C18 on salivary secretion measured immediately or 30 min after the injection. Salivary secretion was measured at three-day intervals, the time the mice require to fully recover from stimulated salivation after anesthesia. Treatment with VX-770 increased salivation in wild-type and NOD mice that reached maximum after 6–9 days and returned to baseline within 3 days after stopping the VX-770 treatment in NOD but not in wild-type mice (Fig. 1a). C18 had no effect on salivation in wild-type mice but significantly increased salivation by the NOD mice in 6 days and was effective for the 24 days of the experiment. Salivary gland activity decreased to baseline within 3 days after stopping C18 treatment (Fig. 1b).

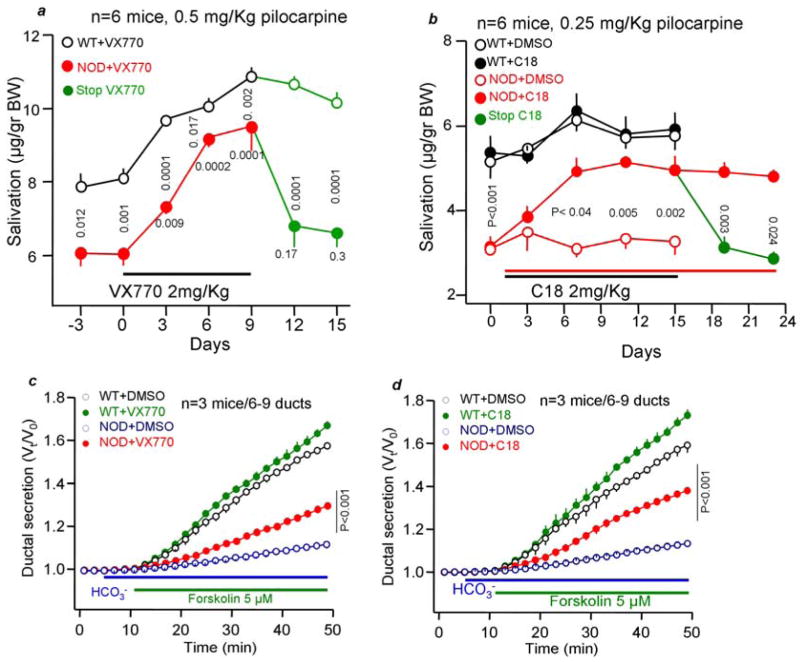

Figure 1. Treating NOD mice with the potentiator VX770 and the corrector C18 restore salivation and ductal fluid secretion.

Wild-type and NOD mice were treated daily by I.P. injection of the solvent DMSO or 2 mg/kg VX770 (a) or 2 mg/kg C18 (b) for the indicated days and salivation in response to pilocarpine stimulation was measured every 3 days for 20 min. At day 9 (VX770) or 15 (C18) injection was stopped in 3 mice to determine the rate of return to pretreatment state. The numbers indicate the p values with respect to pretreatment (horizontal) and to wild-type (vertical). In (c, d) mice were treated with DMSO or VX770 (c) or C18 (d) for 14 days. The ducts were micro-dissected from the parotid glands, cultured for 24–36 hrs with the respective drugs to obtain sealed ducts and used to measure ductal fluid secretion. Here and in all other Figures the results are shown as mean±s.e.m of the indicated number of experiments. When error bars are not visible, they are within the size of the symbols.

The effect of drug treatment on ductal fluid secretion was tested is isolating intralobular ducts from mice treated with VX-770 or C18 for 14 days. Ducts were then maintained in culture media containing 5 μM of the respective drug and ductal fluid secretion was measured by the sealed ducts technique. Figures 1c, d show that salivary glands ducts of NOD mice had minimal fluid secretion. Treating mice with VX-770 and C18 restored ductal fluid secretion by about 30% and 50%, respectively (Fig. 1c).

Treatment with C18 restores CFTR expression in NOD mice

The immunolocalization and quantification of CFTR by Western blots in Figures 2a, c revealed markedly reduced expression CFTR protein in submandibular glands (SMG) of NOD mice. In wild-type SMG CFTR is in the duct luminal membrane, while in NOD SMG many ducts lack CFTR (Figure 2a, c), and when present CFTR localization was fragmented and diffuse (Figure 2a inserts). Treatment with VX770 had minimal effect on the level and localization of CFTR (Figure 2a). By contrast, treatment with C18 restored normal CFTR expression and luminal localization (Figure 2c).

Figure 2. Effect of treating NOD mice with VX770 and C18 on CFTR expression and inflammation.

Wild-type and NOD mice were treated with VX770 (a, b) or C18 (c–e) for 14 days and expression of CFTR was analyzed by immunostaining and protein level (a, c). Protein levels were normalized to actin and then averaged. Inflammation was analyzed by viewing infiltration in H&E stained sections and analysis of the number and size of the inflammatory foci (b, d). In (e) SMG sections were stained for CD3 (upper, T cells) and CD68 (lower, Neutrophils) to assay infiltration.

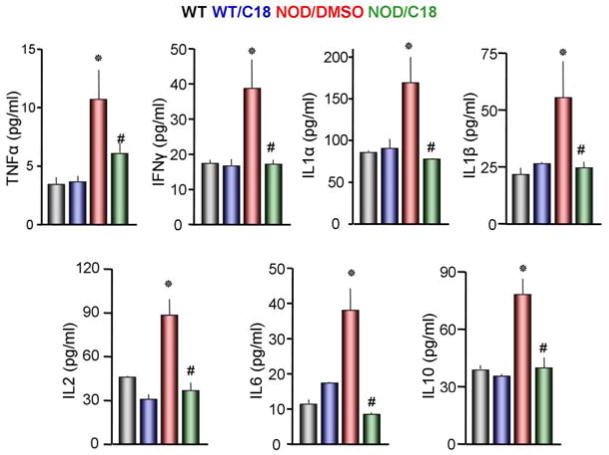

Treatment with C18 reduces inflammation and tissue damage in NOD mice salivary glands

Secretory gland diseases are associated with infiltration of inflammatory cells, inflammation, and tissue damage6, 8. Therefore, we analyzed these parameters in mice treated with VX-770 and C18. Treating the mice with VX-770 reduced the number of focal infiltrates and their size by about 40% (Figure 2b). C18 was more effective than VX-770 in reducing the number and size of the focal infiltrates, which were reduced by about 75% (Figure 2d). In addition, C18 treatment reduced infiltration of T and B cells (Figure 2e). Accordingly, further analysis was done mostly with mice treated with C18. Analysis of inflammatory mediators (Figure 3) shows that all tested mediators are elevated in the NOD salivary glands, TNFα, INFγ, IL1α, IL1β, IL2, IL6 and IL10. Notably, treatment with C18 reduced the level of all inflammatory mediators to the level found in wild-type mice. Tissue damage was assayed by trichrome staining, which detects connective tissue in damaged area. Figure S2 shows that salivary glands and pancreatic damage in the NOD mice was reduced after 14 days of treatment with either VX-770 or C18.

Figure 3. Treating NOD mice with C18 inhibits inflammatory mediators.

Inflammatory mediators were measured in extracts prepared from submandibular glands of wild-type mice injected with DMSO (black) or C18 (blue) and NOD mice treated with DMSO (red) or C18 (green) for 14 days. Each group included 4 mice. * denote p<0.05 or better relative to wild-type and # denote p<0.05 or better relative to DMSO treated NOD mice.

Treatment with VX-770 and C18 reduces pancreatic damage in NOD, MRL/Mp and MRL/Mp-Fas mice

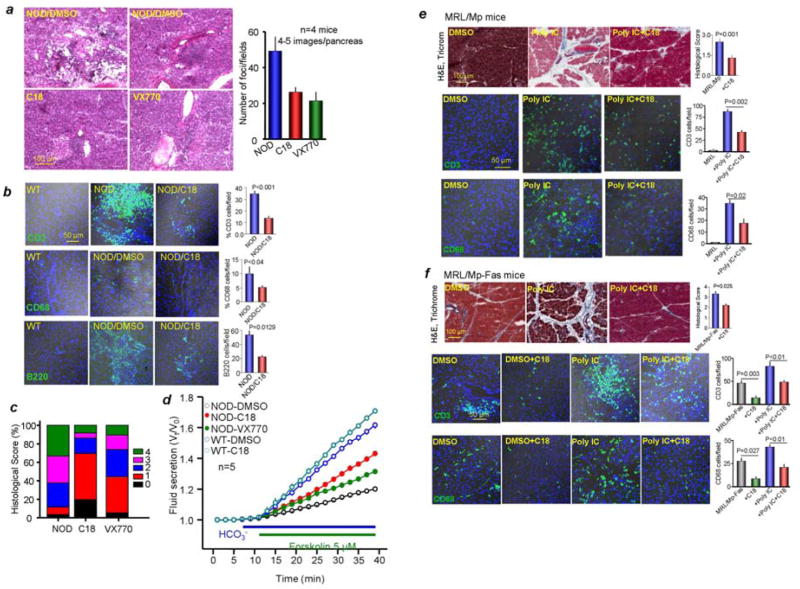

Another disease observed in NOD mice is inflammation of the pancreas25 that is also observed in the MRL/Mp and MRL/Mp-Fas models of AIP26, 27. Accordingly, Figures 4a, b and S2b, show inflammatory foci and high level of collagen in the endocrine (islet in Figure 4a, top left image) and exocrine pancreas that is infiltrated by T and B cells and neutrophils. Treatment with VX-770 and C18 reduced the inflammation, as evident from reduced number of foci (Figure 4a), infiltrates (Figure 4b) and inflammatory scores 4 and 3 (Figure 4c) and tissue damage (Figure S2b). Finally, Figure 4d shows that pancreatic ductal fluid secretion is markedly reduced in NOD mice and treatment with VX-770 or C18 partially rescued the secretion.

Figure 4. Treating NOD mice with the VX770 and C18 and MRL/Mp and MRL/Mp-Fas mice with C18 improved ductal function and reduced inflammation.

Wild-type and NOD mice treated with VX770 or C18 for 14 days were used to evaluate number of foci (a), infiltration of T cells (CD3), macrophages (CD68) and B cells (B220) (b), and inflammation score according to Kanno et. al.31 (c). In (d), the pancreatic intralobular ducts were micro-dissected from mice treated with DMSO, VX770 or C18, cultured for 24–36 hrs and used to measure fluid secretion. In (e, f) MRL/Mp (e) or MRL/Mp-Fas mice (f) treated with and without Poly IC were treated with DMSO or C18 for 14 days and were used to evaluate tissue damage by histological score, T cells (CD3) and macrophages (CD68) infiltration.

To extend the finding in NOD mice to a more established models of AIP we used MRL/Mp treated with Poly IC27 with MRL/Mp mice treated with DMSO used as controls. Figure 4e shows that treatment with C18 reduced the pancreatic damage and infiltration of T cells and neutrophils in MRL/Mp mice. Only minimal infiltration of B cells was noted with these mice (not shown). We also used MRL/Mp-Fas mice treated with Poly IC. MRL/Mp-Fas mice at 12–17 weeks of age develop multiple autoimmune disorders, including lupus, glomerulonephritis and AIP34. Figure 4f shows modest infiltrate in the pancreas of 14 weeks old MRL/Mp-Fas mice that was reduced by treatment with C18 (4 mice). The MRL/Mp-Fas mice were also treated with Poly IC to determine whether C18 treatment can reduce AIP phenotype even in the context of severe autoimmune disorders. Treating the mice with poly IC dramatically increase the pancreatic damage and infiltrate (Figure 4f). Treatment with C18 had modest effect in two mice but nearly eliminated pancreatic damage and infiltrate in two mice. The average of all mice is shown in Figure 4f.

Repairing the ducts repairs the acini in NOD and MRL/Mp mice

In many autoimmune diseases, tissue damage is attributed to impaired acinar cells7–10. However, it is clear that the ducts are also affected in these diseases3, 11. Moreover, the ducts are the first to experience insults and inflammatory foci are mostly periductal35, 36. Since in salivary glands most fluid secretion is mediated by acinar cells1, the finding that correction of CFTR in the ducts resulted in recovery of salivary secretion raised the very important possibility that repairing the ducts is sufficient to repair the acinar cells. We set to test this directly using several assays.

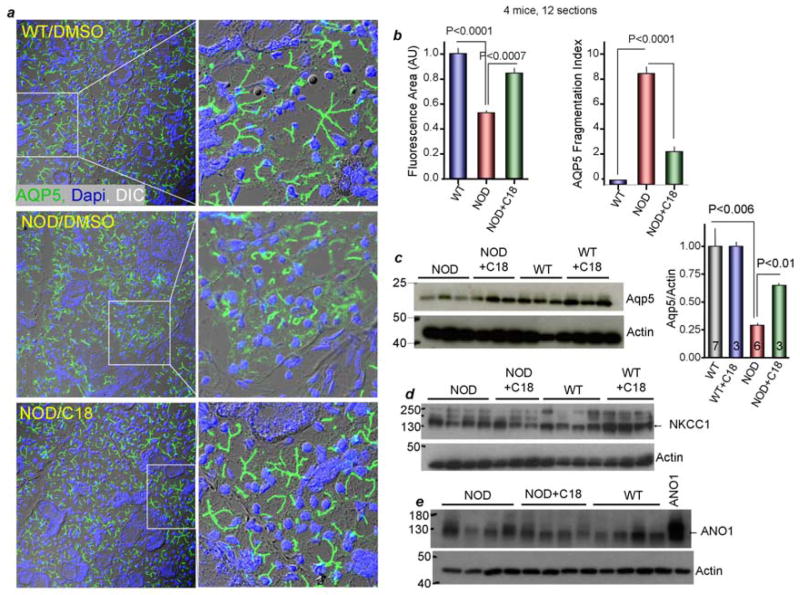

Salivary gland acinar cells fluid secretion is mediated by salt uptake across the basolateral membrane mediated mostly by the Na+/K+/2Cl− cotransporter NKCC1, K+ efflux mediated by Ca2+-activated K+ channels, and the luminal Ca2+-activated Cl− channel Anoctamin 1 (ANO1). Luminal water exits through the water channel aquaporin 5 (AQP5)1, 2. Analysis of these proteins in the salivary glands of untreated and treated NOD mice is shown in Figure 5. The level of NKCC1 and of ANO1 (Figures 5d, e) are not different between wild-type and NOD salivary glands. By contrast, the level of AQP5 is lower by 75% in NOD SMG and it was restored back to about 60% of wild-type by treating the mice with C18 (Figure 5c). Similarly, staining for AQP5 and analysis of the fluorescent area showed reduced area with AQP5 that was restored by C18 treatment (Figure 5a, b). Moreover, even when expressed, AQP5 appeared fragmented in many areas of the glands, in particular next to inflammatory foci (magnified in Figure 5a) and the fragmentation was reduced by C18 treatment (Figure 5a, b).

Figure 5. Treating NOD mice with C18 restore acinar cells AQP5 expression.

AQP5 in acinar cells was evaluated by immunostaining (a) and protein level (c) in wild-type and NOD mice treated with C18. The immunostaining was analyzed for fragmentation by measuring the intensity and length of the stains (b). Expression level of NKCC1 and ANO1 were also analyzed (d, e).

The trigger of serous cells fluid and electrolyte secretion is an increase in cytoplasmic Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) evoked by stimulation of G protein coupled receptors, most prominently the muscarinic M3 receptors1, 2. The receptor-evoked Ca2+ signal includes generation of IP3 that activates the IP3 receptors channel (IP3Rs) to release Ca2+ from the ER. Ca2+ release is followed by activation of plasma membrane Ca2+ influx by the store-operated (SOC) Orai1 and selective members of the TRPC channels. Ca2+ is then removed from the cytoplasm by the plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase pump PMCA and the SR/ER Ca2+ ATPase pump SERCA. Repeat of this cycle results in Ca2+ oscillations, whereas strong stimulation results in a peak-plateau type Ca2+ signal37. Recent studies reported reduced IP3Rs in minor salivary glands of Sjögren’s syndrome patients38. Therefore, we set to analyze in detail the effect of repairing the duct on acinar cells Ca2+ signaling.

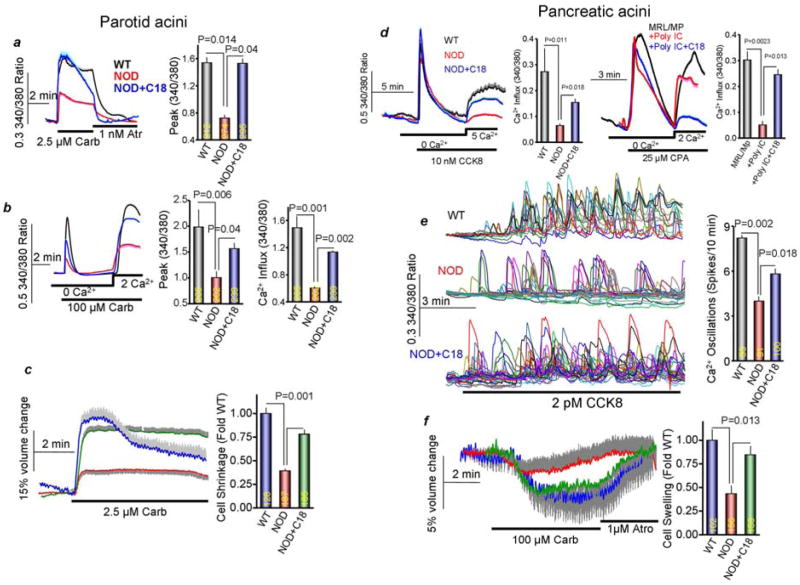

Figure 6a shows reduced receptor-evoked increase in [Ca2+]i in parotid acinar cells of NOD mice stimulated with 2.5 μM carbachol that was fully restored by treating the mice for 10 days with C18. Stimulation of the acini with 100 μM carbachol in Ca2+-free media and re-addition of external Ca2+ showed that both Ca2+ release from stores and Ca2+ influx are impaired in NOD acinar cells and are largely restored by treatment with C18 (Fig. 6b).

Figure 6. Effect of C18 treatment on Ca2+ signaling and fluid secretion by salivary glands and pancreatic acini.

Dispersed acini prepared from the parotid glands of NOD mice (a, b) or the pancreas of NOD and MRL/Mp mice (d, e) treated with DMSO or C18and were used to measure [Ca2+]i in response to stimulation with 2.5 μM carbachol in Ca2+-containing media (a), or 100 μM carbachol (b) in Ca2+-free media and then perfusing with solution containing 2 mM Ca2+ to evaluate Ca2+ influx (d). Pancreatic acini in Ca2+-free media were stimulated with 10 nM CCK8 or 25 μM CPA (d, MRL/Mp mice) and after return of [Ca2+]i to basline they were perfused with a solution containing 5 or 2 mM Ca2+ (d). Acini from NOD mice were also stimulated with 2 pM CCK8 to evaluate Ca2+ oscillations (e). Parotid (c) and pancreatic (f) acini loaded with the cell volume reporter calcein were stimulated with 2.5 (c) or 100 μM carbachol (f). Note the different cell volume scale for parotid and pancreatic acini.

Notably, Ca2+ influx was similarly reduced in pancreatic acini of NOD and MRL/Mp mice (Figure 6d), although pancreatic acini Ca2+ release from stores appeared normal but Ca2+ influx was markedly reduced. The reduced Ca2+ influx resulted in a reduction in receptor-evoked Ca2+ oscillations in NOD pancreatic acini (Fig. 6e). Significantly, treatment with C18 partially restored Ca2+ influx in NOD and MRL/Mp acinar cells (Figure 6d) and Ca2+ oscillations in NOD pancreatic acini (Fig. 6d, e).

Reduced receptor-evoked Ca2+ release and Ca2+ influx can result from reduction in IP3Rs and Orai1 channel expression and localization, respectively, or from reduced Ca2+ content in the stores. Supplementary figure S3 shows that Ca2+ content in stores measured by their passive release with the SERCA pump inhibitor CPA in Ca2+-free solution is the same in wild-type and NOD mice and is not significantly affected by treatment with C18. On the other hand, the SOC-mediated Ca2+ influx evaluated by re-adding external Ca2+ to cells with depleted Ca2+ stores is reduced in parotid and pancreatic acini from NOD mice and it is repaired by treating the mice with C18 (Fig. S3a, d). The same findings were observed with the MRL/Mp pancreatic acini treated with CPA (Figure 6d). The findings in Figs. 6 and S3 imply that reduced Ca2+ release from stores is due to reduced IP3Rs expression/function, at least in salivary glands cells, and reduced Ca2+ influx is due to reduced Orai1 expression/function. This is confirmed for salivary glands acini showing reduced expression of Orai1 (Fig. S3b) and IP3Rs (Fig. S3c) in NOD acini that was largely reversed by treating the mice with C18.

Restoring acinar cells Ca2+ signaling, AQP5 expression and salivation in NOD mice is expected to increase acinar cells fluid secretion. Activation of fluid secretion in salivary gland acinar cells results in large water efflux and can be observed as marked cell shrinkage38. Pancreatic acini are relatively poor fluid secretors1 and their fluid secretion is followed by water influx and can be observed as a modest cell swelling. Figs. 6c and 6f show that fluid fluxes in the respective salivary and pancreatic NOD acinar cells is low but is largely restored to wild type levels by treatment with C18.

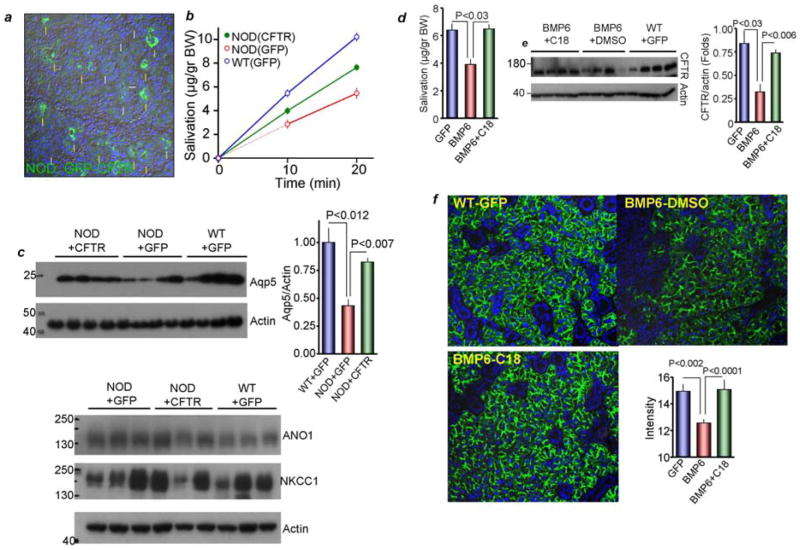

Ductal expression of CFTR reproduce the effect of C18 in NOD mice

Treatment with C18 likely affects all tissues expressing CFTR and reduces systemic inflammation. This raised the question if targeted expression of CFTR in the salivary gland ducts of NOD mice is sufficient to restore salivation and glandular function. To address this, we delivered GFP-tagged human CFTR to the duct by a retroductal infusion of adenoviruses carrying hCFTR or GFP as a control through the oral cavity ductal opening to the SMG glands. Fig. 7a shows the exclusive expression of hCFTR in about 50–60% of the NOD mice ducts. Fig. 7b shows about 50% increase in salivation by NOD mice transduced with hCFTR. The parotid glands and SMG each contribute about 50% of the saliva in the mouse39. Thus, transduction of hCFTR to the SMG of NOD mice completely restored salivation by these glands. Importantly, expression of CFTR in the duct was sufficient to restore expression of AQP5 in acinar cells with no measured change in expression of ANO1 or NKCC1 (Fig. 7c).

Figure 7. Expression of hCFTR in NOD submandibular gland ducts and treating BMP6 expressing glands with C18 restore salivation, AQP5 and CFTR expression.

Ad5-GFP (control) or Ad5-GFP-hCFTR were infused into the SMG and after 7 days the mice were used to probe expressed of GFP-hCFTR (a) measure salivation (b) and expression of AQP5, ANO1 and NKCC1 (c). The salivary glands of wild-type mice were infused with AAV5 vector carrying GFP (control) or BMP6 to over-express BMP6 in the SMG. After six months the mice were treated with C18 for 14 days and used to measure salivary secretion (d), native CFTR (e) and AQP5 expression (f).

Treatment with C18 restores salivation, CFTR expression and AQP5 in the BMP6 model of Sjögren’s syndrome

To extend the findings with C18 to another model of Sjögren’s syndrome, we used C57 mice that express BMP6 in the salivary gland28. The mRNA and protein level of BMP6 were found to be markedly elevated in salivary glands of Sjögren’s syndrome patients and over-expression of BMP6 in salivary glands was sufficient to reproduce the disease symptoms in mice, with reduced salivation, expression of AQP5, and increased lymphocytic foci40. Fig. 7d shows that treating the BMP6 mice with C18 for 10 days restored salivation. Moreover, CFTR levels are markedly reduced in the BMP6 mice and they were significantly restored by treatment with C18 (Fig. 7e). We confirmed the reported reduced level of acinar cells AQP5 in the BMP6 mice and, notably, treatment with C18 restored acinar AQP5 expression (Fig. 7f).

Discussion

The autoimmune diseases Sjögren’s syndrome and AIP damage the salivary glands and the pancreas resulting in xerostomia6 and pancreatic insufficiency, respectively10. Secretory glands are also damaged by radiation and drug therapies41, alcohol consumption, ductal obstruction and bile reflux5. The cause of the diseases is traditionally focused on damage to acinar cells. The present findings indicate that damage to the duct due to degradation and mislocalization of CFTR is central to the pathology. Most notably, correction of CFTR expression and localization in animal models of Sjögren’s syndrome and AIP effectively restored ductal, acinar and organ functions, offering a promising new treatment modality for secretory gland diseases.

Although secretory gland diseases are attributed mostly to damaged acinar cells, several studies indicate damage to the duct. Thus, exposure to bile acids and alcohol metabolites damage duct cells11 to the extent seen in acinar cells42 and inflammatory cell foci are found periductal35, 36. Significantly, CFTR is mislocalized in AIP and in patients with alcoholic, obstructive and idiopathic pancreatitis16, 17. We reasoned that pharmacological correction of ductal function should improve glandular function. Correction of ductal function by C18 treatment is due to restoring CFTR expression (Fig. 2) and fluid secretion (Fig. 1). Since CFTR is not mutated in the mice and diseases affecting CFTR expression16, 17, it is likely that the inflammation/cell stress direct CFTR to the proteasome where it is degraded and the correctors redirect it to the plasma membrane. The potentiators likely activate the residual plasma membrane CFTR. Improved ductal and gland functions by both C18 and VX770 offers the possibility of treating Sjögren’s syndrome and pancreatitis patients with combined therapy, as is done with CF patients43.

The most prominent finding of the present work is that repairing the duct is sufficient to effectively restore the acini and gland functions. It is well established that acinar cells functions are impaired in these diseases. A consistent finding in Sjögren’s syndrome patients and animal models is the reduced level AQP540. Recent work suggests this results in a change in membrane water permeability and introduction of aquaporin 1 into the salivary glands of NOD double congenic Aec1/Aec2 mice and BMP6 expressing mice increases salivary activity and reduce inflammation40. Recent work also reported reduced expression of IP3 receptors in Sjögren’s syndrome minor salivary glands38. Aberrant acinar cells Ca2+ signaling and necrosis are hallmarks of all forms of pancreatitis, including AIP42. No effective treatment is available for treating most forms of acute or chronic pancreatitis, although AIP is treated with corticosteroids16. However, to what extent impaired ductal function contributes to the secretory gland diseases and whether correcting ductal function can improve disease outcome are not known. The main conclusion of the present work is that the acini are largely functional but are damaged as a consequence of aberrant ductal function, at least in Sjögren’s syndrome and AIP. This appear the case even when AIP is severe and in combination with other organs damage, as observed in MRL/Mp-Fas mice (Figure 7f). The most likely scenario is that the autoimmune disease initiates the inflammation around the duct, which results in persistent degradation of CFTR, inhibition of ductal fluid secretion, and blockage of the duct leading to increased inflammation. This will retard the flow of material secreted by acinar cells, resulting in degradation of acinar cell proteins, including IP3Rs, Orai1 and AQP5 to inhibit acinar secretion resulting in damaged acinar cells. Feed forward effect of this process is progressive destruction of the parenchyma. Increasing CFTR expression (C18) and activity (VX770), increases ductal fluid secretion and clearance of the inflammation to allow repair of cell damage. This results in reduced degradation of CFTR, Ca2+ signaling proteins, AQP5 to restore acinar cell function and fluid secretion.

The current findings, suggesting that autoimmune and inflammatory diseases do not attack the acini, at least in early stage of the disease, but rather damage ductal function due to the inflammation. The damage to the acini is secondary to the damage to the duct, and only later the acini may cause self-damage. This is a new concept in understanding and treating autoimmune and inflammatory diseases of secretory glands. It should be applicable to other inflammatory diseases of organs that express CFTR, such as the intestine and the lung. In the intestine, salmonella-induced enteritis causes mislocalization of CFTR44 and there is a strong correlation between CFTR function and asthma45. Treatment with CFTR correctors may offer another tool to treat these diseases.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions: MZ, MS, MA, CZ and HY performed experiments; JAC, RJB and SM directed studies; SM drafted the manuscript with contribution by all authors.

Conflict of interests: All authors declare no conflict of interests. Funded by NIH intramural grant DE DE000735-06

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lee MG, Ohana E, Park HW, et al. Molecular mechanism of pancreatic and salivary gland fluid and HCO3 secretion. Physiological reviews. 2012;92:39–74. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melvin JE, Yule D, Shuttleworth T, et al. Regulation of fluid and electrolyte secretion in salivary gland acinar cells. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:445–69. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.041703.084745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong JH, Park S, Shcheynikov N, et al. Mechanism and synergism in epithelial fluid and electrolyte secretion. Pflugers Arch. 2014;466:1487–99. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1390-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buchwald M. Cystic fibrosis: from the gene to the dream. Clin Invest Med. 1996;19:304–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lerch MM, Gorelick FS. Models of acute and chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1180–93. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ambrosi A, Wahren-Herlenius M. Update on the immunobiology of Sjogren’s syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2015;27:468–75. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox PC, Speight PM. Current concepts of autoimmune exocrinopathy: immunologic mechanisms in the salivary pathology of Sjogren’s syndrome. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1996;7:144–58. doi: 10.1177/10454411960070020301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barrera MJ, Bahamondes V, Sepulveda D, et al. Sjogren’s syndrome and the epithelial target: a comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2013;42:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Criddle DN. Reactive oxygen species, Ca(2+) stores and acute pancreatitis; a step closer to therapy? Cell Calcium. 2016;60:180–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2016.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sah RP, Garg P, Saluja AK. Pathogenic mechanisms of acute pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2012;28:507–15. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3283567f52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hegyi P, Rakonczay Z., Jr The role of pancreatic ducts in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2015;15:S13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pan.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guy-Crotte O, Carrere J, Figarella C. Exocrine pancreatic function in cystic fibrosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:755–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Choi JY, Muallem D, Kiselyov K, et al. Aberrant CFTR-dependent HCO3- transport in mutations associated with cystic fibrosis. Nature. 2001;410:94–7. doi: 10.1038/35065099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitcomb DC. Genetics of alcoholic and nonalcoholic pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2012;28:501–6. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328356e7f3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaRusch J, Jung J, General IJ, et al. Mechanisms of CFTR functional variants that impair regulated bicarbonate permeation and increase risk for pancreatitis but not for cystic fibrosis. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004376. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ko SB, Mizuno N, Yatabe Y, et al. Corticosteroids correct aberrant CFTR localization in the duct and regenerate acinar cells in autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1988–96. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maleth J, Balazs A, Pallagi P, et al. Alcohol disrupts levels and function of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator to promote development of pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:427–39. e16. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nandoskar P, Wang Y, Wei R, et al. Changes of chloride channels in the lacrimal glands of a rabbit model of Sjogren syndrome. Cornea. 2012;31:273–9. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182254b42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flores AM, Casey SD, Felix CM, et al. Small-molecule CFTR activators increase tear secretion and prevent experimental dry eye disease. FASEB J. 2016;30:1789–97. doi: 10.1096/fj.201500180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rowe SM, Verkman AS. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator correctors and potentiators. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013:3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galietta LJ. Managing the underlying cause of cystic fibrosis: a future role for potentiators and correctors. Paediatr Drugs. 2013;15:393–402. doi: 10.1007/s40272-013-0035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramsey BW, Davies J, McElvaney NG, et al. A CFTR potentiator in patients with cystic fibrosis and the G551D mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1663–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goralski JL, Davis SD. Improving complex medical care while awaiting next-generation CFTR potentiators and correctors: The current pipeline of therapeutics. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2015;50(Suppl 40):S66–73. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braley-Mullen H, Yu S. NOD.H-2h4 mice: an important and underutilized animal model of autoimmune thyroiditis and Sjogren’s syndrome. Adv Immunol. 2015;126:1–43. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freitag TL, Cham C, Sung HH, et al. Human risk allele HLA-DRB1*0405 predisposes class II transgenic Ab0 NOD mice to autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:281–91. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asghari F, Fitzner B, Holzhuter SA, et al. Identification of quantitative trait loci for murine autoimmune pancreatitis. J Med Genet. 2011;48:557–62. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2011.089730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwaiger T, van den Brandt C, Fitzner B, et al. Autoimmune pancreatitis in MRL/Mp mice is a T cell-mediated disease responsive to cyclosporine A and rapamycin treatment. Gut. 2014;63:494–505. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yin H, Cabrera-Perez J, Lai Z, et al. Association of bone morphogenetic protein 6 with exocrine gland dysfunction in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome and in mice. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:3228–38. doi: 10.1002/art.38123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong JH, Muhammad E, Zheng C, et al. Essential role of carbonic anhydrase XII in secretory gland fluid and HCO3 (−) secretion revealed by disease causing human mutation. J Physiol. 2015;593:5299–312. doi: 10.1113/JP271378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang CL, Zhu X, Wang Z, et al. Mechanisms of WNK1 and WNK4 interaction in the regulation of thiazide-sensitive NaCl cotransport. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115:1379–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI22452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanno H, Nose M, Itoh J, et al. Spontaneous development of pancreatitis in the MRL/Mp strain of mice in autoimmune mechanism. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;89:68–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb06879.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Potash AE, Wallen TJ, Karp PH, et al. Adenoviral gene transfer corrects the ion transport defect in the sinus epithelia of a porcine CF model. Mol Ther. 2013;21:947–53. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park S, Shcheynikov N, Hong JH, et al. Irbit mediates synergy between ca(2+) and cAMP signaling pathways during epithelial transport in mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:232–41. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King JK, Philips RL, Eriksson AU, et al. Langerhans Cells Maintain Local Tissue Tolerance in a Model of Systemic Autoimmune Disease. J Immunol. 2015;195:464–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kramer JM. Early events in Sjogren’s Syndrome pathogenesis: the importance of innate immunity in disease initiation. Cytokine. 2014;67:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deshpande V, Gupta R, Sainani N, et al. Subclassification of autoimmune pancreatitis: a histologic classification with clinical significance. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:26–35. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182027717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahuja M, Jha A, Maleth J, et al. cAMP and Ca(2)(+) signaling in secretory epithelia: crosstalk and synergism. Cell Calcium. 2014;55:385–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teos LY, Zhang Y, Cotrim AP, et al. IP3R deficit underlies loss of salivary fluid secretion in Sjogren’s Syndrome. Sci Rep. 2015;5:13953. doi: 10.1038/srep13953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kondo Y, Nakamoto T, Jaramillo Y, et al. Functional differences in the acinar cells of the murine major salivary glands. J Dent Res. 2015;94:715–21. doi: 10.1177/0022034515570943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lai Z, Yin H, Cabrera-Perez J, et al. Aquaporin gene therapy corrects Sjogren’s syndrome phenotype in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:5694–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601992113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saleh J, Figueiredo MA, Cherubini K, et al. Salivary hypofunction: an update on aetiology, diagnosis and therapeutics. Arch Oral Biol. 2015;60:242–55. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerasimenko JV, Gerasimenko OV, Petersen OH. The role of Ca2+ in the pathophysiology of pancreatitis. J Physiol. 2014;592:269–80. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.261784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boyle MP, Bell SC, Konstan MW, et al. A CFTR corrector (lumacaftor) and a CFTR potentiator (ivacaftor) for treatment of patients with cystic fibrosis who have a phe508del CFTR mutation: a phase 2 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:527–38. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marchelletta RR, Gareau MG, McCole DF, et al. Altered expression and localization of ion transporters contribute to diarrhea in mice with Salmonella-induced enteritis. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1358–1368. e1–4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maurya N, Awasthi S, Dixit P. Association of CFTR gene mutation with bronchial asthma. Indian J Med Res. 2012;135:469–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.