Abstract

Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a rare cutaneous eruption, most often caused by commonly used antibiotics. It is characterised by an acute onset of non-follicular sterile pustular rash and erythema within hours or days of drug exposure and usually resolves spontaneously within 1–2 weeks once the drug is discontinued. Haemodynamic involvement in the form of shock is rare. Here, we present a severe case of AGEP, manifesting with systemic involvement and haemodynamic instability resulting in shock with multiorgan dysfunction. The associated drugs were erythromycin and fluconazole with a possible combined effect of these two drugs that resulted in systemic involvement. Our patient improved markedly, both haemodynamically and dermatologically, after discontinuation of the drugs and with systemic steroid therapy.

Keywords: dermatology, contraindications and precautions, skin, drug interactions

Background

Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a rare condition which presents with rapid onset of several non-follicular sterile pustules occurring diffusely on an oedematous and erythematous background.1 2 Systemic manifestations are typically restricted to fever and leucocytosis. Reversible mild hepatic and kidney injury have been reported in some cases.1 3 AGEP is caused by drugs in 90% of the cases3 and spontaneously resolves rapidly after the offending agent has been discontinued. Topical steroids are used for symptom relief and systemic steroids have been used in atypical severe presentations with systemic involvement.4 5 Here, we describe a unique case of erythromycin and fluconazole induced severe form of AGEP presenting with shock requiring vasopressors and multiorgan dysfunction requiring CVVHD. Despite prompt discontinuation of the offending agent, patient's condition continued to deteriorate until systemic steroids were initiated.

Case presentation

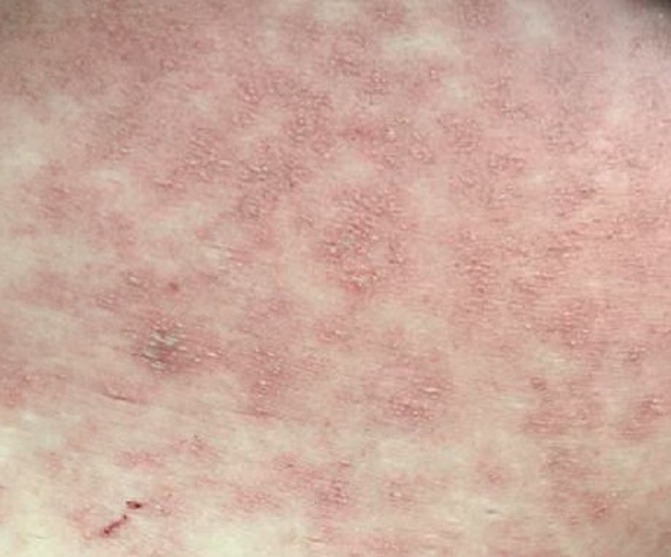

A 61-year-old man with morbid obesity, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus was admitted to the hospital for a 1-week history of acute onset rapidly progressive diffusely erythematous rash within the deep folds of his pannus and in the intertriginous areas. He never had this type of rash previously. The rash was refractory to over-the-counter topical nystatin therapy which the patient had used at home for 5 days prior to admission. On initial presentation, the rash was suspicious for candidal intertrigo based on the appearance of the rash and presence of risk factors (obesity, DM). Erythrasma was also high on the differential diagnosis based on coral red florescence noted with woods lamp, appearance of the rash and presence of risk factors (obesity and DM). As such the patient was started empirically on oral erythromycin and oral fluconazole for possible erythrasma and candidal intertrigo since the rash was extensive. Within 3 days, the patient's rash spread diffusely across his trunk and extremities to form erythematous morbilliform papules which coalesced to form plaques (figures 1 and 2). Within 12 hours of noticeably worsening rash, the patient acutely decompensated, became short of breath and developed metabolic and respiratory acidosis, requiring transfer to the intensive care unit. He was initially started on BiPAP, however, due to increasing somnolence he was intubated. He was noted to be hypotensive, not responsive to intravenous fluid resuscitation. Patient was started on vasopressor support with norepinephrine. He also developed shock liver and acute kidney failure requiring CVVHD.

Figure 1.

Erythematous, oedematous morbilliform papules and plaques in the axilla.

Figure 2.

Non-follicular pustules on an erythematous base with focal areas of desquamation on the trunk.

Investigations

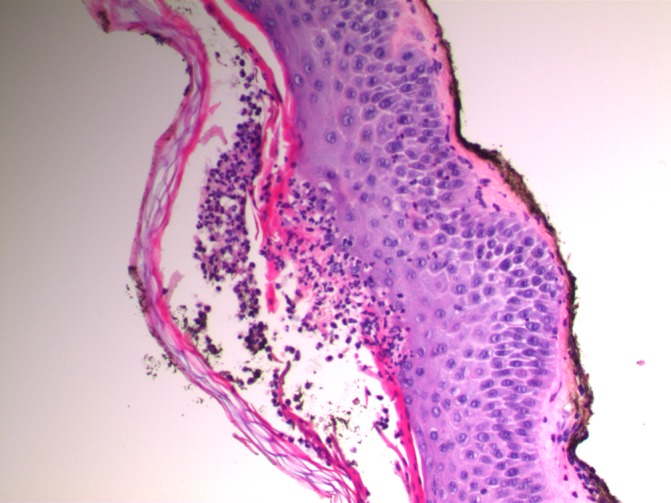

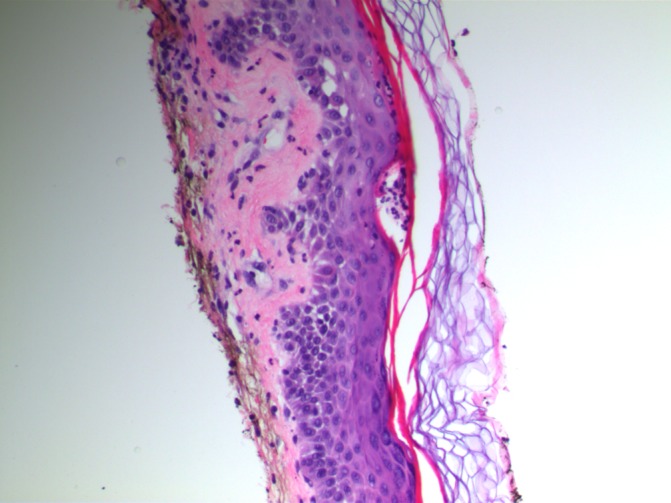

Investigations included Complete Blood Count which revealed neutrophilic leucocytosis (white blood cell 31.10× 109/L), Basic Metabolic Profile and Arterial Blood Gas Analysis which showed acute kidney failure (creatinine of 3.06 mg/dL, hyperkalaemia of 6.3 mmol/L and phosphorus of 7.0 mg/dL), metabolic and respiratory acidosis. Liver Function Tests were consistent with shock liver (AST of 4902 units/mL and an ALT of 3073 units/mL). Infectious workup was negative and included—CXR which was normal. CT chest/abdomen and pelvis failed to reveal any focal signs of infection. Blood and urine culture were negative for any bacterial, fungal growth. Superficial wound culture grew Streptococcus agalactiae, rare Proteus mirabilis, rare Klebsiella and coagulase-negative Staphylococcus—polymicrobial growth which was expected of a skin swab. Skin biopsy was performed which later showed diffuse spongiosis, as well as numerous subcorneal pustules filled with a mixed inflammatory infiltrate, predominately consisting of neutrophils, with some associated lymphocytes, establishing a diagnosis of AGEP (figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

Skin biopsy showing subcorneal pustule.

Figure 4.

Skin biopsy showing subcorneal neutrophils and spongiosis.

Differential diagnosis

Other differentials included septic shock, pustular psoriasis, toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) and Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS). While these differential diagnoses were possible, they were less likely. A comprehensive evaluation, including a thorough physical examination, CXR, CT scan, blood and urine cultures did not reveal any infectious aetiology, making Septic Shock less likely. Although the clinical manifestations of AGEP and pustular psoriasis are similar and at times can be difficult to distinguish, it was less likely to be pustular psoriasis for several reasons. Aside from the classic skin biopsy findings described above, the abrupt onset, short duration and rapid improvement after drug withdrawal support AGEP compared with a prolonged duration with quiescence and recurrence over the course of years in pustular psoriasis. Additionally, the patient had no evidence of arthritis, nor did he have a personal or family history of psoriasis, which would be more consistent with pustular psoriasis. Finally, this was less likely to be TEN or SJS as well there was no mucous membrane involvement in our patient, as well as the latency period between drug exposure and clinical manifestations is often prolonged in these syndromes compared with AGEP.

Treatment

Erythromycin and fluconazole were immediately discontinued on acute decompensation. Due to concern for septic shock initially, he was started on broad spectrum antibiotics, with vancomycin, meropenem and micafungin. However, when the infectious workup was negative, antibiotics were discontinued. With suspicion of AGEP, he was treated with methylprednisolone 80 mg every 8 hours for 3 days and eventual slow taper on oral steroids.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient had marked improvement in both haemodynamics and rash once started on steroids. He no longer required vasopressor agents and was extubated on day 3 of methylprednisolone. He required 4 days of CVVHD and had complete recovery of both kidney and liver function. He was maintained on oral prednisone with slow taper for 2 weeks.

Discussion

AGEP is a relatively rare cutaneous condition provoked by drugs mainly by anti-infective agents, less commonly by infections3 4 and sometimes the cause remains unclear. It is believed to be a T-cell mediated neutrophilic inflammation and the histological hallmark is a spongiform subcorneal/intraepidermal pustule. The rash typically starts in the intertriginous area, as seen in our patient, or the face and rapidly spreads to involve the rest of the body. Systemic manifestations are typically just limited to include fever and neutrophilic leucocytosis and organ involvement is rare. In a few patients, mild hepatic and kidney dysfunction has been reported.1 3 6 Our case of AGEP was an atypical presentation with severe systemic involvement leading to haemodynamic instability and multiorgan dysfunction, thereby giving an illusion of septic shock. Macrolides are a known causative agent and there has been a case report of fluconazole causing AGEP as well. However, to the best of our knowledge, there have been only a few reported cases of AGEP with such severe presentation and none of these cases were associated with the use of erythromycin and fluconazole.7 8 In most of the severe presentations, vancomycin was the culprit medication.7 8 It is possible that the combined effect of erythromycin and fluconazole which are both hepatically metabolised and alter each other's metabolism leading to increased drug levels resulted in the drug reaction being severe with systemic involvement as an affect.

Other differentials to consider would be pustular psoriasis, SJS and TEN. The patient had no history of psoriasis and the concern for SJS and TEN was low based on the history, lack of mucosal involvement and the timing of the drug eruption within a few days of the antibiotics. The diagnosis was more in favour of AGEP which was later confirmed by the biopsy results.

Treatment of AGEP involves prompt removal of the offending agent which typically leads to improvement in symptoms within a few days. Topical steroids can be used for symptom relief. Systemic steroids are not indicated, but have been used in rare cases with severe presentations such as in our case, but currently there is not enough data to support the use of systemic steroids to reduce the duration of the symptoms and early recovery.4 5 9 10

Learning points.

Acute generalised exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) is a rare cutaneous drug eruption, which can be severe and mimic septic shock. It should be suspected in patients being managed for septic shock with negative infectious workup, where the patient's condition continues to deteriorate while on anti-infective agents.

The case illustrated empiric use of anti-infective agents on suspicion of infection, but the infectious workup was negative. This lays emphasis on being cautious while using antibiotics without confirmation of infection.

Several medications have been known to cause AGEP, but it is unclear as to which factors contribute to its severity.

Our patient had pre-existing conditions of morbid obesity, COPD, hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. However, so far no relation of AGEP to the above mentioned comorbidities has been described in the literature.

Discontinuation of the culprit agent might not always result in clinical improvement, especially in severe cases and there might be a role for systemic steroids to promote early clinical recovery

Footnotes

Contributors: MJ conceived, designed, wrote the summary, background,discussion and edited the entire manuscript. CB contributed the case presentation, Investigations, treatment and follow-up part of the manuscript. SR provided intellectual input, drafting and critical revision of the final manuscript. MJ is the overall guarantor of the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sidoroff A, Halevy S, Bavinck JN, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)--a clinical reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol 2001;28:113–9. 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.028003113.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sidoroff A, Dunant A, Viboud C, et al. Risk factors for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)-results of a multinational case-control study (EuroSCAR). Br J Dermatol 2007;157:989–96. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08156.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roujeau JC, Bioulac-Sage P, Bourseau C, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. analysis of 63 cases. Arch Dermatol 1991;127:1333–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choi MJ, Kim HS, Park HJ, et al. Clinicopathologic manifestations of 36 korean patients with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a case series and review of the literature. Ann Dermatol 2010;22:163–9. 10.5021/ad.2010.22.2.163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee HY, Chou D, Pang SM, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: analysis of cases managed in a tertiary hospital in Singapore. Int J Dermatol 2010;49:507–12. 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04313.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Speeckaert MM, Speeckaert R, Lambert J, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: an overview of the clinical, immunological and diagnostic concepts. Eur J Dermatol 2010;20:425–33. 10.1684/ejd.2010.0932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mawri S, Jain T, Shah J, et al. Vancomycin-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) masquerading septic shock-an unusual presentation of a rare disease. J Intensive Care 2015;3:47 10.1186/s40560-015-0114-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohyuddin GR, Al Asad M, Scratchko L, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Am J Crit Care 2013;22:270–3. 10.4037/ajcc2013987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang SL, Huang YH, Yang CH, et al. Clinical manifestations and characteristics of patients with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis in Asia. Acta Derm Venereol 2008;88:363–5. 10.2340/00015555-0438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): A review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;73:843–8. 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]