Abstract

Introduction

An ageing population has become an urgent concern for Asia in recent times. In nursing homes, polypharmacy has also become a compounding issue. Deprescribing practice is an evidence-based strategy to provide a better outcome in this group of patients; however, its implementation in nursing homes is often challenging, and prospective outcome data on deprescribing practice in the elderly is lacking. Our study assesses the implementation of team-care deprescribing to understand the benefits of this practice in geriatric setting and to explore the factors affecting deprescribing practice.

Methods and analysis

This multicentre prospective study consists of a prestudy interview questionnaire, and a preintervention and postintervention study to be conducted in the nursing home setting on residents at least 65 years old and on five or more medications. We will employ a cluster randomised stepped-wedge interventional design, based on a five-step (reviewing, checking, discussion, communication and documentation) team-care deprescribing practice coupled with the use of a deprescribing guide (consisting of Beers and STOPP criteria, as well as drug interaction checking), to assess the health and pharmacoeconomic outcome in nursing homes’ practice. Primary outcome measures of the intervention will consist of fall risks using a fall risk assessment tool. Other outcomes assessed include fall rates, pill burden including number of pills per day, number of doses per day and number of medications prescribed. Cost-related measures will include the use of cost–benefit analysis, which is calculated from the medication cost savings from deprescribing. For the prestudy interview questionnaire, findings will be analysed qualitatively using thematic analysis.

Ethics and dissemination

This study is approved by the Domain Specific Review Board of National Healthcare Group, Singapore (2016/00422) and Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (2016-1430-7791). The study findings shall be disseminated in international conferences and peer-reviewed publications. The study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02863341), Pre-results

Keywords: Deprescribing, Elderly, Falls, Multidisciplinary, Nursing home, Polypharmacy

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first deprescribing study in Asia to be carried out in the nursing home setting and incorporate the investigation of health outcomes using a stepped-wedge design.

Our five-step team-care deprescribing practice is structured using updated evidence-based 2015 Beers criteria and 2014 STOPP criteria.

The study entails a novel three-way comparison of structured team-based deprescribing practice, with existing non-team-based deprescribing practice and with deprescribing-naïve nursing home participants.

The main limitation of the study is that by being conducted only in one country, the findings may not be reflective of all Asian settings.

Introduction

Asia’s population is rapidly ageing, and the elderly accounts for more than half of the global elderly population in 2015. This population is expected to increase by another 66% to 844.5 million in the next 15 years.1 This demographic transition in the elderly is expected to pose a significant challenge for many health authorities worldwide as an advancing age is associated with multiple chronic diseases. Many of current guidelines are based on a healthy adult population, and much less information is available for the geriatric population. However, prescribing in the elderly based on guidelines for younger adults can result in several issues, including polypharmacy, increase pill burden and thus risk of adverse events.2

Nursing homes have one of the highest rates of polypharmacy,3 with almost one-half of nursing home residents exposed to potentially inappropriate medications, and a likely increasing prevalence over time.4 A recent study in Malaysia identified an average of 6.1 medication-related problems per nursing home resident.5 In Singapore, a nursing home study showed that residents were on more than five medications on average. Polypharmacy and inappropriate medication use were seen in 58.6% and 70% of residents, respectively, and there was significant association between polypharmacy and inappropriate medication use.6 Furthermore, the number of readmission is significantly associated with the number of medications prescribed.7 Thus, the growing problem of polypharmacy in the elderly may be addressed through deprescribing.

There is now growing evidence to support that the discontinuation of specific medications or deprescribing in elderly population does not worsen outcomes while decreasing adverse drug events and medication costs.8 9 Deprescribing is increasingly adopted in many countries including Australia, New Zealand, United States, Canada, and several European countries, as reflected from a recent review,10 but is limited in Asia. The principles of deprescribing include reviewing all current medications, identifying medications to be ceased, substituted or reduced, planning a partnership with the patient and frequently reviewing and supporting the patient11 and should be applied in the nursing home setting as well.12

Deprescribing is important in reducing polypharmacy, risk of adverse medication outcome and medical care cost while improving compliance.13 However, there is a lack of prospective outcome data on deprescribing practice in elderly in an Asian population, especially in the nursing home settings. Our study will assess a team-based deprescribing intervention on falls risk and falls rate, as well as pharmacoeconomic outcomes in nursing homes and explore the factors affecting deprescribing practice. In particular, our primary outcome measure of falls risk and falls rate will be important as falls cascade down to other medical and related economical issues. Primary outcome measures of the intervention will consist of fall risks using a fall risk assessment tool (FRAT). Other outcomes assessed include fall rates, pill burden including number of pills per day, number of doses per day and number of medications prescribed and cost-related measures including cost–benefit analysis (CBA).

Aims of the study

The aims of this study are to examine: (1) the effectiveness of a five-step team-care deprescribing intervention in a nursing home setting in reducing falls risk, falls rate, pill burden and medication cost, and (2) the factors that affect the acceptance of deprescribing among healthcare professionals. We hypothesise that a team-care deprescribing intervention initiated by the pharmacists will provide better health (through a reduction in falls risk and falls rate) and economic outcomes versus usual care in a nursing home setting.

Methods and analysis

Participants and settings

This study will be a longitudinal preinterventional and postinterventional study conducted in a nursing home setting. The study setting would comprise up to four nursing homes in Singapore, with a total capacity of 950 beds, representing 8% of the total nursing home beds in Singapore.14 The nursing home residents are mostly aged 60 years and above, with mobility issue and require daily skilled nursing care or assistance in activities of daily living. The functional status of the residents is determined from Singapore’s Ministry of Health’s Resident’s Assessment Form15 and will be used in the standardisation during our analysis of fall risks and fall rates.

All residents in the nursing homes will be assessed and included if they fulfil the following criteria: (1) aged 65 years and above, (2) currently on five or more medications and (3) provided informed consent (unless cognitive impaired, with no or uncontactable next of kin). Consent from next of kins will be sought for cognitive-impaired participants. Principal investigator will seek consent from next of kins and participants. Participants will be excluded if they have a life expectancy of less than 6 months (based on patient’s physician/general practitioner judgement) or staying for respite care. Participants will be discontinued from the study if there is admission into hospital for longer than 30 days, passed away or on discharged back to home or moved to another nursing home.

Study design

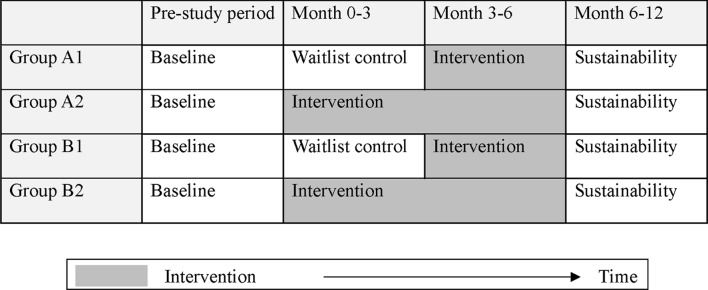

This study will employ a stepped-wedge design, which involves sequential crossover from control to intervention, until all cluster groups receives the intervention.16 We decided to employ this design due to its pragmatic approach, as it does not deprive any participant from receiving an evidence-based intervention (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The stepped-wedge design for the current study. Baseline population of each home is subclassified into two groups (groups A and B). Group As are non-naive (participants whose attending doctor or pharmacist has recently deprescribed their medications within 6 months before the study starts), while the group Bs are intervention naive. Intervention will be implemented to first half of the participants in 3 months. Each home thus has four clusters, and all clusters will be assessed for sustainability of outcomes after 6 months.

Sample size considerations

Sample size was calculated based on the main clinical outcome, which is falls rate reduction. Our literature search found that the Asian elderly annual fall rate is 18%,17 and we expect that the intervention will reduce the fall rate by a further 10%. Assuming a 5% significance, 80% power and an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.1, we calculated that we need 54 participants per arm for the stepped-wedge trial with four different arms. Allowing for a 25% attrition rate, a total of 288 participants will be recruited.

Randomisation and blinding

This study will employ a stratified cluster randomised design with the cluster groups as the unit of randomisation. The investigator conducting analyses will be using coded information of participants located in the nursing homes during data analysis. Participants will know what medication they are taking, as per usual practice.

Intervention

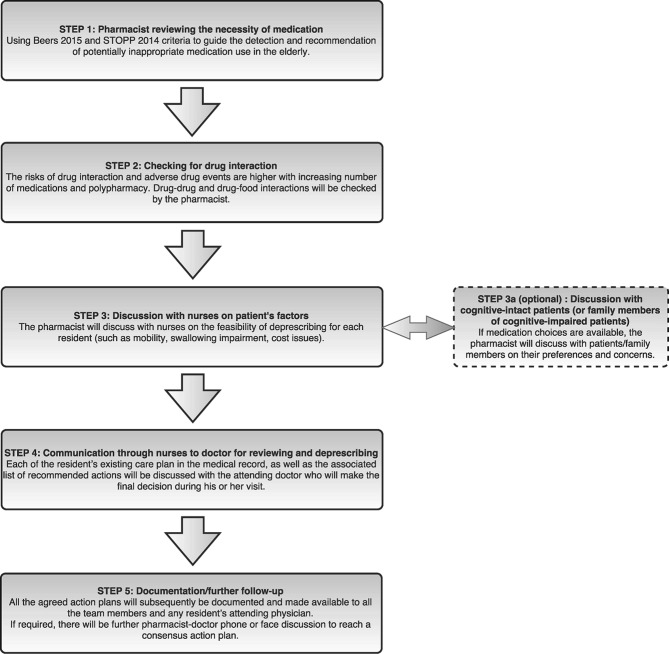

The intervention will consist of a five-step multidisciplinary team-based deprescribing approach using a deprescribing guide adapted from the Beers criteria,18 Screening Tool of Older People’s Prescriptions (STOPP) criteria,19 as well as a review of medication interactions and side effects.

The five-step team-care process consists of reviewing, checking, discussion, communication and documentation as described in figure 2, initiated by the pharmacists. Each nursing home in the study is currently served by one to two community-based pharmacists. They have completed or are currently undertaking their postgraduate studies (Master of Clinical Pharmacy) or Board Certified Geriatric Pharmacist training. All pharmacists (minimum working experience at aged care homes of 1 year) will receive a half-day face-to-face training and familiarisation session on the intervention. Our multidisciplinary team-care approach involves nurses, pharmacists and doctors and will be implemented during routine doctor and pharmacist nursing home review visits. Pharmacists will initiate deprescribing in medication review, after discussion with ward nurses on the feasibility of deprescribing for each appropriate individual patient. The intervention information filled-up by the pharmacist will be passed on through the ward nurses to the doctor for review during doctor’s visit. Thereafter, the doctor will make the final decision on drugs that will be deprescribed. A copy of the deprescribing reference guide (Beers and STOPP criteria) will be available to all participating healthcare professionals. The Beers and STOPP criteria are intended as a guide for educating pharmacists and doctors regarding the different types of interventions that they could make. For successful deprescribed patients with external institution follow-up, a copy of the deprescribing details will be pass as memorandum to the external doctor. Additionally, multidisciplinary discussion session may be introduced as part of the nursing home’s standard practice at some sites, but implementation depends on case-by-case availability and agreement of individual doctor, pharmacist and nurse at each site during routine care. Non-cognitive impaired residents or next of kins of cognitive-impaired residents may be contacted in decision making of the intervention where feasible.

Figure 2.

Five-step team-based deprescribing practice.

Control

All participants in the control arm will continue to receive usual care or support that they usually receive from their healthcare professionals. In participants who were randomised to control, there is a possibility that some participants will require a review of their medication. These patients will be documented and analysed separately at the end of study.

Data collection

Data collection from both intervention and control groups will occur at four time points (baseline, month 3, month 6 and month 12). The data include the FRAT scores, fall rate, pill burden, medication intervention acceptance and reduction rates as well as costs. Principal investigator and study team will be in charge of the data monitoring. Data management procedures have been reviewed by the ethics board with the frequency of review at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months.

In addition, a prestudy interview questionnaire with doctors, pharmacists and nurses will be conducted to determine the factors that affect their views and acceptability of deprescribing. The anonymous prestudy interview questionnaire will consist of 10 open-ended questions covering knowledge, practice and attitude towards deprescribing. The principal investigator will approach potential participants at the study sites during routine visits by convenience sampling, and the short prestudy interview questionnaire will enrol up to 10 doctors, pharmacists and nurses (total 30 participants) each to collect qualitative data on deprescribing. We will provide a qualitative analysis of the views of these participants.

Outcomes and study measures

Primary outcome

Fall risks: Assessments of fall risk will be compared preintervention and postintervention using the FRAT.20 Our adapted FRAT will cover additional elements including medical conditions, history of falls, contributing medications, functional status, as well as behavioural issues, as recommended by local fall risk assessment guideline. The primary outcome is the mean change in FRAT scores at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months.

Secondary outcomes

Fall rate: Actual fall rates will be compared between baseline preintervention period and the intervention period (proportion of participants who experiencing a fall 1 year prestudy and 1 year poststudy). A fall was defined as any incident reported as a fall in the progress notes.

Pill burden: Number of pills per day, number of doses per day and number of medication will be compared predeprescribing and postdeprescribing at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months.

Medication reduction rate: Percentage of reviewed cases where medications are deprescribed will be compared between baseline preintervention period and the intervention period. The total number of regular medicines comprised all regular and as-needed medicines that is in the resident’s medication record. It also includes supplements and complementary or alternative medicine.

Cost related: CBA is constructed from cost savings postdeprescribing. This will be calculated from medication review expenditure, utilisation expenditure and medication cost. The direct medication cost saved from deprescribing is compared with any increment in manpower cost by tracking the number of reviews completed by pharmacists. The number of reviews completed will be tracked monthly.

Factors affecting deprescribing: Findings from thematic analysis of data from our exploratory prestudy standardised interview questionnaire covering factors on knowledge, practice and attitude towards deprescribing for healthcare professionals (doctors, nurses and pharmacists) will be presented.

In addition to the outcomes above, we will also be assessing the acceptance rate of the deprescribing intervention (number of pharmacist interventions accepted by doctor monthly), as well as the type and percentage of drug-related problems. Charlson comorbidity index and medication regimen complexity index will be tabulated from the collected data. We will also collect data on the number of STOPP criteria and Beers criteria interventions made. In addition, we will assess any harm associated with the intervention by comparing hospitalisation and mortality rates. These data together with the primary outcomes will subsequently be used in our pharmacoeconomic analysis.

Statistical analysis

All analysis will be performed following intention-to-treat principle. The characteristics of the patient population will be determined using appropriate descriptive statistics. χ2 tests will be used to compare proportions, and analysis of variance will be used for comparing continuous data. A p value of <0.05 will be considered statistically significant for all tests.

The effectiveness of the current study intervention will be measured by determining the differences with respect to change to activities performed and events data. In addition, the presence of significant separate time trends within subgroups will be examined, as analytical methods employed in stepped-wedge trials are vulnerable to it. Confounding of time will be accounted for during data analysis by stratified analysis or multiple variable regression analysis.

Fall risks and fall rates within and between groups will be tested for significant difference. Pill burden (number of pills per day, number of doses per day and number of medication) will be tabulated under descriptive statistics and compared using t-tests. Subgroup analysis will be further performed for successfully and unsuccessfully deprescribed subjects. Medication deprescribed will be further classified based on their primary indication in subgroup analysis.

CBA will be conducted to analyse the economic benefits of the deprescribing intervention. Parameters that will be examined include medication cost, time spent for medication review and utilisation expenditure. CBA will be derived from the medication cost divided by the pharmacist manpower cost, between the intervention and control groups. The average hourly cost of pharmacist review will be used in the calculation.

The 10 open-ended interview questionnaire involving doctors, pharmacists and nurses will be qualitatively analysed using thematic analysis. The interview questionnaire will be transcribed verbatim, and audio-recording is by participant’s consent. We will use QSR NVivo 11 to assist in analysis of the data, and both inductive approach as well as deductive approach will be used in our analysis.21 In conventional content analysis (inductive approach), we will conduct a regression analysis to determine the various demographic and clinical characteristics of our participants that can affect success of deprescribing. These will be used to develop themes and subthemes for the thematic analysis, as well as to develop a coding scheme. Following which, we will also be using directed content analysis (deductive approach), using the interview questions to collect qualitative data and the transcript data placed into themes or subthemes.

Discussion

Deprescribing is not yet widely practised in Asian settings but has been strongly advocated in many countries including Singapore.22 We have adopted the pioneering principle from Woodward,11 which looks at discontinuation, substitution and reduction, as these can also be related to our application of the latest Beers criteria. In our nursing home settings, a large proportion of participants are cognitive impaired and will not be able to engage in some of the published protocols23 24 due to communication capabilities. As such, our study will look at the deprescribing process that aims to discontinue, substitute and reduce medication.

Our multicentre prospective nursing home study will encompass an evaluation of a five-step multidisciplinary team-based deprescribing intervention on health and pharmacoeconomic outcomes in an Asian nursing home setting. This is supplemented by a prestudy interview questionnaire that will enable the exploration of the views of local healthcare professionals towards deprescribing. This work will add knowledge in the field of geriatric care and address important outcomes applicable for an escalating global ageing population.

By employing an innovative stepped-wedge design, our study will allow each study group to act as its own control and preserve the internal validity of the study.25 This design is particularly suited for ethical evaluation of service delivery intervention,26 and we expected it to be especially applicable in long-term care facilities such as nursing homes.

We anticipate a few challenges for the study. In participants who were randomised to waitlist control, some participants may require an early review of their medication before crossing over to intervention. These patients will be documented and analysed separately at the end of study, although this will inevitably dilute down the results of the control group. Another challenge in our population is that a large number of residents are cognitive impaired, and thus may have limited capabilities to be involved in decision making, or participate in the prestudy interview questionnaire. Their next of kins may not be contactable as well.

bmjopen-2016-015293supp001.doc (122.5KB, doc)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Karla Hemming for sharing her insights on our stepped-wedge design.

This study protocol is presented according to the SPIRIT 2013 checklist (see online supplementary data).

Footnotes

Contributors: C-HK drafted the manuscript and is the principal investigator. C-HK, CYYY, SWHL, VSLM and IY-OL participated in the design of the study presented in the manuscript. C-HK, CYYY, CWTC, CWYT and PCT will be conducting the study. All authors have reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Domain Specific Review Board (DSRB) Singapore and Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. United Nations. 2015. World Population Aging. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WPA2015_Report.pdf Accessed 23 Nov 2016.

- 2. Naganathan V. Cardiovascular drugs in older people. Aust Prescr 2013;36:190–4. 10.18773/austprescr.2013.077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tamura BK, Bell CL, Lubimir K, et al. . Physician intervention for medication reduction in a nursing home: the polypharmacy outcomes project. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2011;12:326–30. 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.08.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Morin L, Laroche ML, Texier G, et al. . Prevalence of potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults living in Nursing Homes: a systematic review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2016;17:862.e1–862.e9. 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee SW, Chong CS, Chong DW, Identifying and addressing drug-related problems in nursing homes: an unmet need in Malaysia? Int J Clin Pract 2016;70:512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mamun K, Lien CT, Goh-Tan CY, et al. . Polypharmacy and inappropriate medication use in Singapore nursing homes. Ann Acad Med Singapore 2004;33:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Toh MR, Teo V, Kwan YH, et al. . Association between number of doses per day, number of medications and patient’s non-compliance, and frequency of readmissions in a multi-ethnic Asian population. Prev Med Rep 2014;1:43–7. 10.1016/j.pmedr.2014.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bain KT, Holmes HM, Beers MH, et al. . Discontinuing medications: a novel approach for revising the prescribing stage of the medication-use process. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:1946–52. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01916.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garfinkel D, Mangin D. Feasibility study of a systematic approach for discontinuation of multiple medications in older adults: addressing polypharmacy. Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1648–54. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Page AT, Clifford RM, Potter K, et al. . The feasibility and effect of deprescribing in older adults on mortality and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016;82:583–623. 10.1111/bcp.12975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Woodward MC. Deprescribing: achieving Better Health Outcomes for older people through reducing medications. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research 2003;33:323–8. 10.1002/jppr2003334323 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee SWH, Mak VSL. Changing demographics in Asia: a case for enhanced pharmacy services to be provided to nursing homes. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research 2016;46:152–5. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Garfinkel D, Ilhan B, Bahat G. Routine deprescribing of chronic medications to combat polypharmacy. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2015;6:212–33. 10.1177/2042098615613984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ministry of Health. Health facilities. 2015. Accessed 23 Nov 2016 https://www.moh.gov.sg/content/moh_web/home/statistics/Health_Facts_Singapore/Health_Facilities.html.

- 15. Elderly and Continuing Care Division. A guidebook on nursing homes: Ministry of Health, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hussey MA, Hughes JP. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2007;28:182–91. 10.1016/j.cct.2006.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kwan MM, Close JC, Wong AK, et al. . Falls incidence, risk factors, and consequences in chinese older people: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:536–43. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03286.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American geriatrics society 2015 updated beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;2015:2227–46. 10.1111/jgs.13702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. O’Mahony D, O’Sullivan D, Byrne S, et al. . STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing 2015;44:213–8. 10.1093/ageing/afu145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stapleton C, Hough P, Oldmeadow L, et al. . Four-item fall risk screening tool for subacute and residential aged care: the first step in fall prevention. Australas J Ageing 2009;28:139–43. 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2009.00375.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pharmaceutical Society of Singapore. Polypharmacy in Singapore: the role of deprescribing. 2015. http://www.pss.org.sg/sites/default/files/PW/PW15/1._polypharmacy-deprescribing_position_statement_final_240915.pdf (Accessed 23 Nov 2016).

- 23. Reeve E, Shakib S, Hendrix I, et al. . The benefits and harms of deprescribing. Med J Aust 2014;201:386–9. 10.5694/mja13.00200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. . Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:827–34. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hawkins NG, Sanson-Fisher RW, Shakeshaft A, et al. . The multiple baseline design for evaluating population-based research. Am J Prev Med 2007;33:162–8. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hemming K, Haines TP, Chilton PJ, et al. . The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ 2015;350:h391 10.1136/bmj.h391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015293supp001.doc (122.5KB, doc)