Abstract

Introduction

There is some evidence that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), in particular celecoxib, might possess not only a symptomatic efficacy but also disease-modifying properties in ankylosing spondylitis (AS), retarding the progression of structural damage in the spine if taken continuously. In contrast, this remains controversial for tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors, despite their good clinical efficacy. The impact of a combined therapy (a TNF inhibitor plus an NSAID) on radiographic spinal progression in AS is unclear.

Methods and analysis

The aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of treatment with an NSAID (celecoxib) when added to a TNF inhibitor (golimumab) compared with TNF inhibitor (golimumab) alone on progression of structural damage in the spine over 2 years in patients with AS. The study consists of a 6-week screening period, a 12-week period (phase I: run-in phase) of treatment with golimumab for all subjects followed by a 96-week controlled treatment period (phase II: core phase) with golimumab plus celecoxib versus golimumab alone, and a safety follow-up period of 4 weeks. At week 108, the primary study endpoint radiographic spinal progression (as assessed by the change in the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score after 2 years) will be evaluated.

Ethics and dissemination

The study will be performed according to the principles of good clinical practice and the German drug law. The written approval of the independent ethics committee and of the German federal authority have been obtained. On study completion, results are expected to be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov register (NCT02758782) and European Union Clinical Trials Register (EudraCT No 2016-000615-33).

Keywords: Ankylosing spondylitis, radiographic progression, TNF inhibitors, NSAIDs, mSASS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first prospective randomised controlled multicentre trial with the objective to investigate the effect of a combination of a tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory disease (NSAID) on radiographic spinal progression in ankylosing spondylitis.

The primary outcome measure (radiographic spinal progression) will be evaluated by two independent readers blinded for the time-point and all clinical data including treatment allocation, and is therefore, not affected by the open-label study design.

Patient population consists of patients at high risk of radiographic spinal progression.

Study is conducted only in one country (Germany).

The intervention is not masked/blinded.

Highly selected patient population.

Assumptions made for the sample size calculation are based on data obtained separately for TNF inhibitors and NSAIDs.

Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory disease of unknown aetiology with primary involvement of the axial skeleton (sacroiliac joint (SIJ) and spine), starting in most of the cases in subjects under 45 years of age (mean age onset about 26 years), with a strong association with the major histocompatibility complex class I antigen HLA-B27, which is positive in 80%–90% of the patients.1 Patients with AS can develop peripheral arthritis and enthesitis, as well as extra-articular manifestations such as anterior uveitis, psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease.2 The prevalence of AS is estimated to be between 0.1% and 1.4%.3 The disease is characterised by the presence of active inflammation in the SIJ and the spine, which manifests as pain and stiffness, and by excessive new bone formation (leading to the development of syndesmophytes and ankylosis in the same areas). This results in a significant functional impairment in up to 40% of the patients.4 5 Given the young age at disease onset in the majority of patients, impairment of the functional status in AS causing disability has a relevant socioeconomic impact.6 Reduction of clinical burden and prevention of disability can probably be best achieved by early and adequate treatment targeting both inflammation and new bone formation. According to the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) and European League Against Rheumatism recommendations, the first-line therapy for patients with AS are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), including selective cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX-2) antagonists, along with education and continuous exercise/physiotherapy.7 Therapy with conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) such as sulfasalazine or methotrexate may have some beneficial effect in patients with peripheral joint involvement, but in general is not effective for the treatment of axial involvement.8–10 For those patients who have a poor response to NSAIDs, contraindications or intolerance for NSAIDs, the only effective treatment currently available is the therapy with tumour necrosis factor (TNF) α inhibitors7 or with a recently introduced monoclonal antibody against interleukin-17 secukinumab.11 There is some evidence that NSAIDs, in particular celecoxib, might possess not only a symptomatic efficacy but also disease-modifying properties in AS, retarding the progression of structural damage (syndesmophytes and ankylosis) in the spine if taken continuously.12 This might be explained by a direct inhibitory effect on osteoblast genesis and activity.13 This effect was especially evident in patients with AS with elevated C reactive protein (CRP),14 which is also considered a risk factor for radiographic spinal progression in AS.15 The data from the German Spondyloarthritis Inception Cohort (GESPIC) showed a similar protective effect against radiographic spinal progression in those patients who had high NSAIDs intake (defined as >50% of the maximum recommended dose) and who were at high risk for radiographic spinal progression (due to presence of syndesmophytes and/or elevated CRP) at baseline.16 For diclofenac, a non-selective COX inhibitor, such effect was, however, not proven in a recently published trial.17

The data on the effect of TNF inhibitors on radiographic spinal progression in ankylosing spondylitis—despite their high anti-inflammatory efficacy—remains controversial. While some studies could not show a retardation of radiographic spinal progression in AS over a period of 218–20 or 421 years, there are three observational studies suggesting that it may take more than 4 years to detect such an effect22–24 and that early (within the first 5 or 10 years of the disease) initiation of anti-TNF therapy might play a key role.23 24 However, no prospective controlled trials have been conducted so far to confirm these observations.

Many patients with AS treated with a TNF inhibitor discontinue their NSAIDs due to good symptom control.25 Therefore, it has not been possible until now to answer the question of the impact of a combined therapy (TNF inhibitor and NSAID) on radiographic spinal progression. It is crucial to clarify whether adding an NSAID (especially a COX-2 selective one) to TNF inhibitor treatment is able to stop or reduce radiographic progression, especially in patients at high risk (ie, with elevated CRP and/or with already present syndesmophytes). Recently, results of an observational study indicating inhibition of radiographic spinal progression with a combination of a TNF inhibitor with a high-dose NSAID were presented26 stressing a need for a prospective interventional trial.

The aim of this prospective study is to evaluate the impact of treatment with an NSAID celecoxib added to a TNF inhibitor golimumab compared with golimumab alone on progression of structural damage in the spine over 2 years in patients with AS.

Methods and analysis

Study design

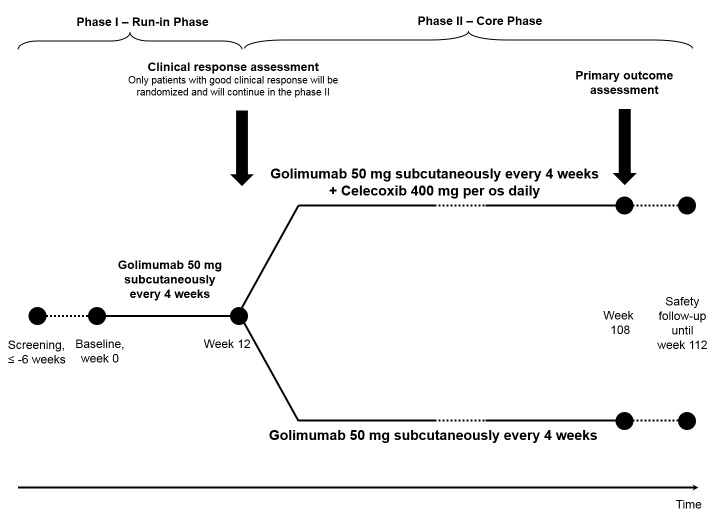

This study is a randomised, controlled, multicentre, open-label clinical trial. The study consists of a 6-week screening period, a 12-week period (phase I: run-in phase) of treatment with golimumab 50 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks for all subjects followed by a 96-week controlled treatment period (phase II: core phase) with golimumab plus celecoxib versus golimumab alone, and a safety follow-up period of 4 weeks (figure 1). Only subjects with a good clinical response to golimumab in the phase I (improvement of the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI) score by ≥2 absolute points on a 0–10 scale response at week 12) will be eligible for phase II and will be randomised based on a 1:1 ratio to receive golimumab 50 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks plus celecoxib (in a daily dose of 400 mg/day) or golimumab 50 mg subcutaneously every 4 weeks alone for another 96 weeks. At week 108, the primary study endpoint (radiographic spinal progression defined as the change in the modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score (mSASSS)27 after 2 years) will be evaluated. MRI of the spine and sacroiliac joints will be performed at baseline (week 0), and at week 108 (or in case of early termination at week 84 or later) in a substudy of approximately 60 patients with no contraindication for this investigation.

Figure 1.

Design of the Comparison of the effect of treatment with Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs added to antitumour necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy versus anti-TNF therapy alone on progression of StrUctural damage in the spine over 2 years in patients with ankyLosing spondylitis (CONSUL) study.

Patients

Included patients will be 18 years and older with AS fulfilling the modified New York Criteria28 with an active disease (BASDAI ≥4), history of an inadequate response to at least two NSAIDs and at least one of the two following risk factors for radiographic spinal progression: elevated CRP or already present syndesmophyte(s) at screening and give written informed consent. Key inclusion and exclusion criteria are shown in table 1. Study participants will be recruited from 21 rheumatological centres throughout Germany between September 2016 and presumably February 2018. One hundred and ninety patients shall be assessed for eligibility (assuming a 10% screening failure rate), so that 170 patients with active AS despite treatment with NSAIDs alone will be included in the phase I of the trial and treated with golimumab. Only patients with good clinical response (BASDAI reduction by ≥2 absolute points (on a 0–10 scale) after 12 weeks of golimumab treatment will be enrolled in the phase II (core phase) of the trial. Based on the efficacy results from a phase III study with golimumab in AS,29 we assume that approximately 60% (n=100) of the patients included in phase I will continue in to phase II of the study. Thus, 100 patients (n=50 in each group) will enter phase II of the trial (intention-to-treat population (ITT) after 1:1 randomisation and will be analysed for the primary and secondary outcome parameters.

Table 1.

Main inclusion and exclusion criteria of the CONSUL study

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Age ≥18 years | Presence of total spinal ankylosis |

| Definite diagnosis of AS according to the modified New York criteria | History of primary non-response to previous anti-TNF therapy (if any) |

| Active disease (defined as BASDAI≥4) | Contraindications for the treatment with golimumab and/or celecoxib |

| History of an inadequate response to a therapeutic trials of at least two NSAIDs | |

| Risk factors for radiographic spinal progression (defined as elevated CRP or existing syndesmophytes) at screening |

AS, ankylosing spondylitis; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; CRP, C reactive protein; NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drugs; TNF, tumour necrosis factor.

Outcome parameters

The study outcome parameters are summarised in table 2. The primary outcome parameter of the study is radiographic spinal progression measured by the change in the mSASSS after 2 years of treatment (primary endpoint). Secondary outcome parameters include new syndesmophyte formation or progression of existing syndesmophytes after 2 years of treatment, change of the bone and cartilage biomarkers serum levels change of the enteric microbiome profile, change of osteitis score and scores for the chronic postinflammatory changes in the spine and sacroiliac joints on MRI by Berlin MRI scoring method (in the MRI substudy only) and improvement of disease activity, function, axial mobility and quality of life. Safety outcome parameters include evaluation of adverse events (AEs), serious AE and AEs of interest: infections, malignancies, gastrointestinal events (ulceration, bleeding, perforation, gastric outlet obstruction), cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke, pulmonary artery embolism, peripheral arterial or venous thrombosis), renal impairment (creatinine >1.8 mg/dL or increase >0.5 mg/dL vs baseline) and substantial (more than fivefold) liver enzyme elevation.

Table 2.

Main outcome parameters of the CONSUL study

| Efficacy | Safety |

Primary endpoint

|

AEs, serious AE and AE of interest until week 112 |

Secondary endpoints

|

AEs, adverse events ASDAS, Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score; ASAS, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; CRP, C-reactive protein; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; mSASSS, modified Stoke Ankylosing Spondylitis Spine Score; NRS, numeric rating scale; PASS, Patient Acceptable Symptom State; PhASS, Physician Acceptable Symptom State.

Data analysis plan

The study consists of a 12-week run-in period, 96-week core period (randomised treatment) and 4-week follow-up period. The primary efficacy endpoint will be the absolute progression of the mSASSS score after 2 years of therapy in both treatment groups. The primary analysis will be based on the mean of the mSASSS scores obtained by two trained readers for the spinal X-rays performed at inclusion in the study and at week 108 in the ITT population. For the purposes of the efficacy and safety analysis, a database lock will occur, once all data up to week 112 has been collected and cleaned.

Statistical analysis

The primary analysis will be based on all patients who entered phase II of the trial (ITT population). Multiple imputation methods with mSASSS score at baseline as covariate will be applied to deal with missing radiographs in the primary analysis. The Mann-Whitney test will be used to compare the primary outcome (change in the mSASSS score) between the treatment groups. Cumulative probability plots will be built to visualise the finding. In a secondary analysis, the Mann-Whitney test will be used to compare radiographic progression in the subgroup of patients with complete sets of radiographs. A likelihood approach will be applied to deal with missing data in secondary outcome parameters assessed at multiple time points. For that reason, linear mixed models will be applied to compare means of secondary outcome parameters over time. A non-responder imputation for missing response data and χ2 tests will additionally be applied to compare response rates. Two-sided p values <0.05 will be considered to be statistically significant.

Sample size justification

The sample size calculation is based on the findings of Kroon et al, 14 our own results from GESPIC Cohort16 and those of Braun et al.21 We assume a worsening in the mSASSS score of 1.7±2.8 in patients of the control group and of 0.2±1.6 in patients with continuous NSAIDs intake. We considered such a difference of 1.5 mSASSS units as clinically relevant and planned the sample size of this study by means of a two-sided (α=0.05) Welch-Satterthwaite t-test accordingly. To detect the mentioned difference with an 80% power, the sample size of n=38 in each group is needed in the phase II of the trail. This is also true if the Mann-Whitney test is applied. However, the power will decrease by the application of multiple imputations to deal with missing radiographs of dropouts in the ITT population. Considering that all subjects enrolled in the phase II will be responders to golimumab therapy receiving this same treatment for the whole period of the trial, along with our experience in conducting randomised controlled trials, we presume dropout rates of less than 20% during phase II. For this reason and based on our own mSASSS data, we expect an increase in the variance of mSASSS progression because of multiple imputation by less than 25%. Considering this possible increase, a sample size of n=100 patients is needed for phase II of the trial to detect the expected and clinically relevant difference of an average 1.5 mSASSS points with an 80% power in the ITT population. In addition, we assumed that 60% of the subjects enrolled in phase I of the study would be eligible for randomisation and participation in phase II (based on the rate of the BASDAI50 response in patients with AS with elevated CRP), giving a total n=170 subjects to be included in the phase I of the trial.

Ethics and dissemination

The study will be performed according to the International Conference of Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the German drug law (Arzneimittelgesetz). The written approval of the central independent ethics committee (Ethics Committee of the Federal State Berlin), of the German federal authority (Paul-Ehrlich-Institut, Langen, Germany) and of the local ethics committees of the study centres have been obtained. On study completion, results are expected to be published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: FP, BM and VRR were involved in drafting the study protocol. JL was involved in statistical planning and drafting the study protocol. JS developed the idea for this trial and was involved in drafting and revising the study protocol. DP conceived the idea for this trial, was involved in drafting and revising the study protocol and was the principal investigator of this trial.

Funding: This work is supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung - BMBF), grant no: FKZ 01KG1603. MSD Sharp & Dohme provides study drug golimumab and supports the MRI substudy.

Competing interests: FP: speaker fees and/or consultancy payments from Novartis, UCB and Roche. BM: consultancy payments from Novartis and UCB. JL: honoraria from Novartis and Pfizer. VRR: none. JS: research grants from Abbvie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer and Roche; speaker fees and/or consultancy payments from Abbvie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Eli Lilly, MSD/Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. DP: research grants from Abbvie, MSD and Novartis; speaker fees and/or consultancy payments from Abbvie, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen, Eli Lilly, MSD/Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche and UCB.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committee of the Federal State Berlin.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Braun J, Sieper J. Ankylosing spondylitis. Lancet 2007;369:1379–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60635-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Winter JJ, van Mens LJ, van der Heijde D, et al. Prevalence of peripheral and extra-articular disease in ankylosing spondylitis versus non-radiographic axial spondyloarthritis: a meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther 2016;18:196 10.1186/s13075-016-1093-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sieper J, Poddubnyy D. Axial spondyloarthritis. Lancet 2017. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31591-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feldtkeller E, Bruckel J, Khan MA. Scientific contributions of ankylosing spondylitis patient advocacy groups. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2000;12:239–47. 10.1097/00002281-200007000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Landewé R, Dougados M, Mielants H, et al. Physical function in ankylosing spondylitis is independently determined by both disease activity and radiographic damage of the spine. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:863–7. 10.1136/ard.2008.091793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Franke LC, Ament AJ, van de Laar MA, et al. Cost-of-illness of rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2009;27(4 Suppl 55):S118–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R, et al. 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2017. 2017. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Braun J, Zochling J, Baraliakos X, et al. Efficacy of sulfasalazine in patients with inflammatory back pain due to undifferentiated spondyloarthritis and early ankylosing spondylitis: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1147–53. 10.1136/ard.2006.052878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haibel H, Rudwaleit M, Braun J, et al. Six months open label trial of leflunomide in active ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:124–6. 10.1136/ard.2003.019174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Haibel H, Brandt HC, Song IH, et al. No efficacy of subcutaneous methotrexate in active ankylosing spondylitis: a 16-week open-label trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:419–21. 10.1136/ard.2006.054098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J, et al. Secukinumab, an interleukin-17A inhibitor, in Ankylosing Spondylitis. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2534–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wanders A, Heijde D, Landewé R, et al. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs reduce radiographic progression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:1756–65. 10.1002/art.21054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Yoon DS, Yoo JH, Kim YH, et al. The effects of COX-2 inhibitor during osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow-derived human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev 2010;19:1523–33. 10.1089/scd.2009.0393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kroon F, Landewé R, Dougados M, et al. Continuous NSAID use reverts the effects of inflammation on radiographic progression in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1623–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-201370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Poddubnyy D, Haibel H, Listing J, et al. Baseline radiographic damage, elevated acute-phase reactant levels, and cigarette smoking status predict spinal radiographic progression in early axial spondylarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:1388–98. 10.1002/art.33465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Poddubnyy D, Rudwaleit M, Haibel H, et al. Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on radiographic spinal progression in patients with axial spondyloarthritis: results from the German spondyloarthritis inception cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1616–22. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sieper J, Listing J, Poddubnyy D, et al. Effect of continuous versus on-demand treatment of ankylosing spondylitis with diclofenac over 2 years on radiographic progression of the spine: results from a randomised multicentre trial (ENRADAS). Ann Rheum Dis 2016;75:1438–43. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Einstein S, et al. Radiographic progression of ankylosing spondylitis after up to two years of treatment with etanercept. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:1324–31. 10.1002/art.23471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van der Heijde D, Landewé R, Baraliakos X, et al. Radiographic findings following two years of infliximab therapy in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:3063–70. 10.1002/art.23901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van der Heijde D, Salonen D, Weissman BN, et al. Assessment of radiographic progression in the spines of patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with adalimumab for up to 2 years. Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:R127 10.1186/ar2794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Braun J, Baraliakos X, Hermann KG, et al. The effect of two golimumab doses on radiographic progression in ankylosing spondylitis: results through 4 years of the GO-RAISE trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1107–13. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-203075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Baraliakos X, Haibel H, Listing J, et al. Continuous long-term anti-TNF therapy does not lead to an increase in the rate of new bone formation over 8 years in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:710–5. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haroon N, Inman RD, Learch TJ, et al. The impact of tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors on radiographic progression in ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2645–54. 10.1002/art.38070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Maksymowych WP, Zheng Y, Wichuk S, et al. The effect of TNF inhibition on Radiographic Progression in Ankylosing Spondylitis: an Observational Cohort Study of 374 patients. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67(suppl 10):1275–6. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dougados M, Wood E, Combe B, et al. Evaluation of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-sparing effect of etanercept in axial spondyloarthritis: results of the multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled SPARSE study. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:481 10.1186/s13075-014-0481-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gensler L, Reveille J, Lee M, et al. High dose nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and tumor necrosis factor Inhibitor Use results in less radiographic progression in Ankylosing Spondylitis – a Longitudinal Analysis [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016;68(Suppl 10):2481–2. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Creemers MC, Franssen MJ, van't Hof MA, et al. Assessment of outcome in ankylosing spondylitis: an extended radiographic scoring system. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:127–9. 10.1136/ard.2004.020503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A. Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum 1984;27:361–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deodhar A, Braun J, Inman RD, et al. Golimumab administered subcutaneously every 4 weeks in ankylosing spondylitis: 5-year results of the GO-RAISE study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:757–61. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.