Abstract

Purpose

There is limited information in administrative databases on the occurrence of serious but treatable complications after hip fracture surgery. This study sought to determine the feasibility of identifying the occurrence of serious but treatable complications after hip fracture surgery from discharge abstracts by applying the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Patient Safety Indicator 4 (PSI-4) case-finding tool.

Methods

We obtained Canadian Institute for Health Information discharge abstracts for patients 65 years or older, who were surgically treated for non-pathological first hip fracture between 1 January 2004 and 31 December 2012 in Canada, except for Quebec. We applied specifications of AHRQ Patient Safety Indicators 04, Version 5.0 to identify complications from hip fracture discharge abstracts.

Results

Out of 153 613 patients admitted with hip fracture, we identified 12 383 (8.1%) patients with at least one postsurgical complication. From patients with postsurgical complications, we identified 3066 (24.8%) patient admissions to intensive care unit. Overall, 7487 (4.9%) patients developed pneumonia, 1664 (1.1%) developed shock/myocardial infarction, 651 (0.4%) developed sepsis, 1862 (1.1%) developed deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism and 1919 (1.3%) developed gastrointestinal haemorrhage/acute ulcer.

Conclusions

We report that 8.1% of patients developed at least one inhospital complication after hip fracture surgery in Canada between 2004 and 2012. The AHRQ PSI-4 case-finding tool can be considered to identify these serious complications for evaluation of postsurgical care after hip fracture.

Keywords: Hip fracture, surgery, patient safety indicators, complications

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study includes all hip fractures (over 150 000) recorded in Canada over an 8-year period.

Compared with a prospective study, observational design is more suitable for determining population-based proportions of postsurgical complications.

This study presents the first application of a case-finding tool to identify five serious but treatable complications after an unplanned procedure—hip fracture surgery.

The case-finding tool focuses on five serious but treatable postsurgical complications, the frequency of all complications after hip fracture will be higher than reported here.

Introduction

Surgery for hip fracture carries a significant risk of death with 7% dying inhospital.1 This mortality risk depends on characteristics of patients, injury and treatment. The occurrence of inhospital death is also associated with postsurgical complications.2 Over 20 years ago, Silber and colleagues suggested inhospital death following postsurgical complications as an indicator of quality of care.3 They based this on the premise that postsurgical complications reflect characteristics of the patient and their injury, whereas death from such complications reflects the process of care.3 4 Miller et al advanced this approach through the concept of preventable death after serious but treatable complications.5

Yet, there is a lack of information in administrative databases on the occurrence of serious but treatable complications after hip fracture surgery.6–8 This makes it difficult to evaluate the effects of care delivery on the risk of postsurgical complications and ensuing inhospital death nationally. However, the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) developed Patient Safety Indicator 4 (PSI-4), Death among Surgical Inpatients with Serious Treatable Complications, and a case-finding tool for screening diagnosis and procedure codes in discharge abstracts of planned surgical procedures.9 This tool allowed research on the quality of postsurgical care leading to the US Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005.10 This study sought to determine the feasibility of identifying the occurrence of serious but treatable complications after hip fracture surgery from discharge abstracts by applying the AHRQ PSI-4 case-finding tool. The University of British Columbia Behavioural Research Ethics Board approved this study.

Methods

Data source

We obtained all discharge abstracts for patients 65 years or older, who were surgically treated for non-pathological first hip fracture between 1 January 2004 and 31 December 2012 in all Canadian hospitals, except for the province of Quebec, which does not participate in this database. Multiple abstracts linked by hospital transfers for the same patient were combined in one care episode.11 We selected only patients who stayed at least 1 day after surgery.

We converted Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) diagnosis and procedure codes from International Classification of Diseases 10th RevisionCanada (ICD-10-CA)/Canadian Classification of Health Intervention (CCI)/Canadian Classification of Procedure (CCP) to ICD-9-Clinical Modification (CM) codes, and discharge dispositions to Uniform Hospital Discharge Data Set (UHDDS) (see online supplementary material 1).

bmjopen-2016-015368supp001.pdf (3.5MB, pdf)

Outcomes

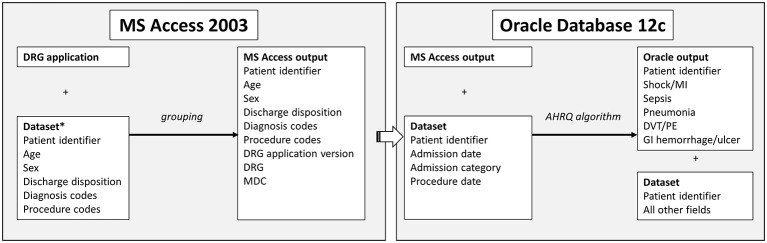

The primary outcome was the occurrence of at least one postsurgical complications listed in AHRQ PSI-4: shock/myocardial infarction, sepsis, pneumonia, deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism and gastrointestinal haemorrhage/acute ulcer.9 We extended the AHRQ specifications to include all older adults, emergency admissions for hip fracture, and surgeries within 4 days of admission (figure 1, table 1).

Figure 1.

Data model for identifying complications from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Patient Safety Indicator 04. MS, Microsoft; DRG, Diagnosis-realated groups; MDC, Major diagnostic categories; PSI, patient safety indicator. *After pre-grouper exclusions.

Table 1.

Specifications for identification of serious treatable complications after hip fracture surgery

| Complication* | Definition† |

| Shock/MI | Numerator: secondary diagnosis code for shock/MI‡ Denominator: surgical discharge, for patients aged ≥65 years with ICD-9-CM code for hip fracture surgery; and surgery within 4 days of admission or urgent admission type Exclude cases: principal diagnosis for shock, MI, haemorrhage, or GI haemorrhage; any listed procedure code for lung cancer resection; major diagnostic category 4 (diseases/disorder of respiratory system) or 5 (diseases/disorders of circulatory system); discharge disposition of transfer to acute care; or missing discharge disposition, age, or sex |

| Sepsis | Numerator: secondary diagnosis code for sepsis‡ Denominator: surgical discharge, for patients aged ≥65 years with ICD-9-CM code for hip fracture surgery; and surgery within 4 days of admission or emergency admission type Exclude cases: principal diagnosis for sepsis or infection; any listed diagnosis or procedure code for immunocompromised state; length of stay <4 days; or discharge disposition of transfer to acute care; or missing discharge disposition, age or sex |

| Pneumonia | Numerator: secondary diagnosis code for pneumonia‡ Denominator: surgical discharge, for patients aged≥65 years with ICD-9-CM code for hip fracture surgery; and surgery within 4 days of admission or emergency admission type Exclude cases: principal diagnosis for pneumonia or respiratory complications; any listed diagnosis code for viral pneumonia, influenza or immunocompromised state; any listed procedure code for lung cancer; major diagnostic category 4 (diseases/disorder of respiratory system) or discharge disposition of transfer to acute care; or missing discharge disposition, age or sex |

| DVT/PE | Numerator: secondary diagnosis code for DVT/PE‡ Denominator: surgical discharge, for patients aged ≥65 years with ICD-9-CM code for hip fracture surgery; and surgery within 4 days of admission or emergency admission type Exclude cases: principal diagnosis for DVT/PE; discharge disposition of transfer to acute care; missing discharge disposition, age or sex |

| GI haemorrhage/ acute ulcer | Numerator: secondary diagnosis code for GI haemorrhage/acute ulcer‡ Denominator: surgical discharge, for patients aged ≥65 years with ICD-9-CM code for hip fracture surgery; and surgery within 4 days of admission or emergency admission type Exclude cases: principal diagnosis for GI haemorrhage, acute ulcer, alcoholism, or anaemia; major diagnostic category 6 (diseases/disorder of digestive system) or 7 (diseases/disorders of hepatobiliary system and pancreas); discharge disposition of transfer to acute care; or missing discharge disposition, age, or sex |

Identified from complications listed in AHRQ QI Research Version 5.0, Patient Safety Indicators 04, Technical Specifications.

Modified from AHRQ QI Research Version 5.0, Patient Safety Indicators 04, Technical Specifications.

Identified from secondary ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes listed in AHRQ QI Research Version 5.0, Patient Safety Indicators 04, Technical Specifications, Death Rate among Surgical Inpatients with Serious Treatable Complications.

DVT, deep venous thrombosis; GI, gastrointestinal; MI, myocardial infarction; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Diagnosis-related groups

To apply the AHRQ case-finding tool, the diagnosis codes from the abstracts must first be assigned to a diagnosis-related group (DRG). The DRG classification system categorises the discharge abstracts into ‘buckets’ according to hospital resource use and clinical homogeneity. We assigned the abstracts to a DRG according to post-admission diagnosis codes, procedure codes, age, sex, discharge disposition and year of discharge.12 DRGs were further aggregated into major diagnostic categories (MDC), according to the principal diagnosis of admission.

We assigned DRGs and MDCs to the discharge abstracts using an MS Access 2003 application (www.drggroupers.net), DRG Masks files f20 (1 October 2002 to 30 September 2003) to f30 (1 October 2012 to 30 September 2013) and select CIHI data fields (figure 1).12 This application accounted for changes in DRG and MDC classification over time. We set the DRG present on admission flag according to the CIHI diagnosis type: ‘yes’ for type 1 and 5, ‘unspecified’ for type M, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 0, W, X and Y. We set the DRG hospital acquired complications flag to ‘false’. We used the CIHI most responsible diagnosis for admission as the principal diagnosis for the DRG.

We applied the following pre-DRG exclusions: missing principal procedure or discharge date, unspecified sex, elective admission with principal procedure more than 4 days after admission, discharge after 30 September 2013, and where conversion from ICD-10-CA/CCI/CCP to ICD-9-CM was not possible.

Analysis

Patient characteristics were expressed as frequencies and proportions. The number of discharges with postsurgical complications, expressed as a proportion of all discharges was used to calculate the incidence of complications after hip fracture surgery. In addition, we established the number of discharges with admission to intensive care unit after hip fracture surgery and calculated the proportion of admissions to intensive care among discharges with the studied postsurgical complications.

Results

Patient characteristics

We studied 153 613 surgically treated patients after the application of pre-DRG exclusions (n=131). The majority of patients were women (73.4%). The median age was 84 years (65–110). Fracture type was evenly distributed between transcervical (52.0%) and trochanteric (48.0%) fractures. Overall, 27.0% had at least one major comorbidity (heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ischaemic heart disease, hypertension, cardiac arrhythmia or diabetes). Cardiac arrhythmias including supra ventricular tachycardia (ICD-10-CA 147), atrial fibrillation and flutter (ICD-10-CA 148) and other such as ventricular premature and atrial premature depolarisation (ICD-10-CA 149) were the most prevalent (9.4%).

DRG assignment

In total, 87% of patients were assigned a DRG of hip and femur procedures or major joint. The remaining patients were assigned a DRG of pathological fractures (7%), multiple major joint procedures (2%) or other (4%). In total,94% of patients were assigned MDC of 08 (Musculoskeletal System and Connective Tissue). The remaining patients were assigned MDC of 23 (3%), 24 (1%) or other (2%).

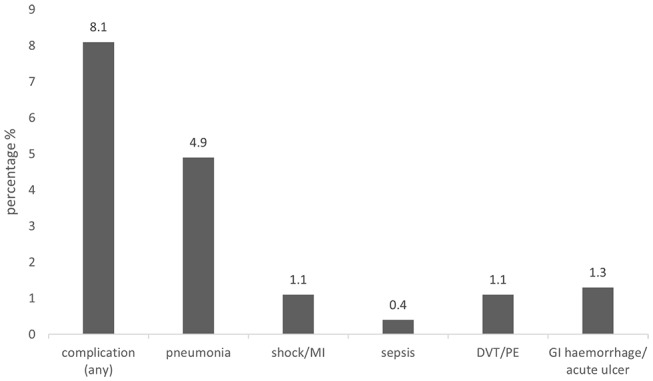

Complications and admissions to intensive care unit

Out of 153 613 patients, we identified 12 383 (8.1%) patients with at least one postsurgical complication and 11 807 (7.7%) admissions to intensive care unit during acute hospitalisation for first hip fracture. Overall, 7487 (4.9%) patients developed pneumonia, 1664 (1.1%) developed shock/myocardial infarction, 651 (0.4%) developed sepsis, 1862 (1.1%) developed deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism and 1919 (1.3%) developed gastrointestinal haemorrhage/acute ulcer (figure 2). Among patients with postsurgical complications, 3066 (24.8%) had admissions to intensive care unit.

Figure 2.

Complications after hip fracture surgery. DVT, deep venous thrombosis; GI, gastrointestinal; MI, myocardial infarction; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Discussion

Main findings

One in 12 patients had at least one complication on their discharge abstract after hip fracture surgery in Canada between 2004 and 2012, with pneumonia being the most prevalent (60.5%). One quarter of surgically treated patients with complications required intensive care treatment during their inpatient stay.

Comparison with other studies

We examined the feasibility of identifying the occurrence of serious but treatable complications after hip fracture surgery from discharge abstracts by applying specifications of AHRQ Quality Indicator Research Version 5.0 for PSI-4. In developing these specifications, the AHRQ subjected the list of complications and their definitions to rigorous clinical review, evaluation of reliability and validation.8 Further, these specifications are continually revised with some complications from the PSI-4 list made available as separate safety indicators, for example, deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism (PSI-12) and sepsis (PSI-13).12

In particular, we report the extent to which our estimated incidence of complications after hip fracture surgery were similar to the US National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) where postsurgical complications are coded prospectively.13 Between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2012, 56 808 patients aged 65 years and older were admitted to a US NTDB acute hospital with a diagnosis codes of hip fracture ICD-9 820. In total, 7.7% patients developed postsurgical complications during hospitalisation for first hip fracture. Therefore, our application of the AHRQ PSI-4 to Canadian hospital discharge abstracts revealed similar rates of complications among adult surgical inpatients in the USA.

In the current study, we report pneumonia as the most frequent complication after hip fracture surgery in Canada. This finding is similar to a UK study where chest infection was the most frequent postsurgical complication.14 Pneumonia is associated with readmission and mortality after hip fracture surgery.15 A recent study reported that over two-thirds of 30-day mortality occurrences after hip fracture surgery were due to pneumonia and acute myocardial infarction.15 An autopsy study of more than 500 deaths after hip fracture surgery reported bronchopneumonia and myocardial infarction as the principal causes of death.16 In the current study, a similar proportion of patients developed shock, myocardial infarction, deep venous or pulmonary embolism, gastrointestinal bleeding or ulcers after hip fracture surgery. Less than 1% of patients developed postsurgical sepsis.

Others reported that death after serious but treatable complications could be considered as a quality indicator for postsurgical care. Studies have shown an association between complications and other measures of hospital quality including mortality, length of stay and readmissions.3 8 17 18

Limitations

Identification of postsurgical complications in administrative databases may vary by the definition of each complication. For example, a search for ‘pneumonia’ returns over 300 results across three medical coding data sets.19 Whether all these results are applicable to the definition of pneumonia as a complication after hip fracture surgery may be debated. Therefore, we focused on the five postsurgical complications after hip fracture surgery as defined by the PSI-4 to facilitate reproducibility of our results. We also focused on admissions to the intensive care unit. The reason for admission to intensive care was not available. Our data showed that three quarters of abstracts with admissions to the intensive care unit did not have the studied complications. These admissions were likely due to other conditions, such as unplanned intubation, wound infection, acute kidney injury, acute respiratory distress syndrome and cerebrovascular accident.14

To account for differences in coding methods between the USA and Canada, we converted ICD-10-CA diagnosis and CCI/CCP procedure codes to ICD-9-CM and discharge dispositions to UHDDS. We acknowledge that the conversion to a less specific coding system leads to losses in precision. We do not believe pre-DRG exclusions would bias results as they represented less than 1% of the total population.

Future research

Here we demonstrated the feasibility of identifying five postsurgical complications in administrative data. Future research should identify additional complications which occur after hip fracture surgery. Future research may also consider a composite outcome of postsurgical complications and intensive care admissions in investigating quality of postsurgical care. Finally, future research should explore the potential associations between patient characteristics, their injury and their care, and the occurrence of postoperative complications and ensuing death.

Conclusions

We report the incidence of 8.1% for inhospital complications among patients who underwent hip fracture surgery in Canada between 2004 and 2012. The AHRQ PSI-4 case-funding tool can be considered to identify these serious complications for evaluation of postsurgical care after hip fracture.

bmjopen-2016-015368supp002.doc (108KB, doc)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. In addition KJS, BS, MT, LK, SS, PG contributed to the acquisition and the analysis of data. KJS, BS, PG, LK, PB, JAB, SNM, DG, SJ, EB, JMS and LB contributed to the interpretation of the analysis. KJS and BS drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version for submission.

Funding: This research was funded by the Canadian Institute for Health Research.

Disclaimer: The funder had no role in the design of this study, execution, analyses, data interpretation or decision to submit results for publication.

Competing interests: The authors declare that (1) BS, PG and the Collaborative have received grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research related to this work. (2) PG also receives funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation and the British Columbia Specialists Services Committee for work around hip fracture care not related to this manuscript. He has also received fees from the BC Specialists Services Committee (for a provincial quality improvement project on redesign of hip fracture care) and from Stryker Orthopedics (as a product development consultant). He is a board member and shareholder in Traumis Surgical Systems Inc. and a board member for the Canadian Orthopedic Foundation. He also serves on the speakers’ bureaus of AO Trauma North America and Stryker Canada. (3)SNM reports research grants from Amgen Canada, and from Merck, personal fees from Amgen Canada outside the submitted work. (4) KJS is a postdoctoral fellow whose salary is paid by Canadian Institutes of Health Research funding related to this work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We studied patient records that were anonymized and de-identified by a third party, the Canadian Institute for Health Information, an organisation which provides researchers access to data on Canadian residents. Data are available from the Canadian Institute for Health Information for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Collaborators: The following are members of the Canadian Collaborative Study on Hip Fractures: EB, LB, Michael Dunbar, DG, PG, Edward Harvey, Erik Hellsten, SJ, Hans Kreder, LK, Adrian Levy, SNM, KJS, BS, JMS and James Waddell.

Reference

- 1. Sobolev B, Guy P, Sheehan KJ, et al. Time trends in hospital stay after hip fracture in Canada, 2004-2012: database study. Arch Osteoporos 2016;11:13 10.1007/s11657-016-0264-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lu-Yao GL, Keller RB, Littenberg B, et al. Outcomes after displaced fractures of the femoral neck. A meta-analysis of one hundred and six published reports. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76:15–25. 10.2106/00004623-199401000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Silber JH, Williams SV, Krakauer H, et al. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with death after surgery. A study of adverse occurrence and failure to rescue. Med Care 1992;30:615–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Ross RN. Comparing the contributions of groups of Predictors: which outcomes vary with hospital rather than patient characteristics? J Am Stat Assoc 1995;90:7–18. 10.1080/01621459.1995.10476483 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miller MR, Elixhauser A, Zhan C, et al. Patient safety indicators: using administrative data to identify potential patient safety concerns. Health Serv Res 2001;36:110–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Menendez ME, Ring D. Failure to rescue after proximal femur fracture surgery. J Orthop Trauma 2015;29:e96–e102. 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Belmont PJ, Garcia EJ, Romano D, et al. Risk factors for complications and in-hospital mortality following hip fractures: a study using the National Trauma Data Bank. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2014;134:597–604. 10.1007/s00402-014-1959-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhan C. Administrative data based patient safety research: a critical review. Qual Saf Health Care 2003;12:58ii–63. 10.1136/qhc.12.suppl_2.ii58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. AHRQ quality indicators: guide to patient safety indicators. version 5.0. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Farley DO, Damberg CL. Evaluation of the AHRQ patient safety initiative: synthesis of findings. Health Serv Res 2009;44:756–76. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00939.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sheehan KJ, Sobolev B, Guy P, et al. Constructing an episode of care from acute hospitalization records for studying effects of timing of hip fracture surgery. J Orthop Res 2016;34:197–204. 10.1002/jor.22997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patient safety indicators technical specifications Updates-Version 5.0.. 2015. http://www.qualityindicators.ahrq.gov/modules/PSI_TechSpec.aspx (accessed 29 Nov 2016).

- 13. NTDB Research Data set and National Sample Program, 2015. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/ntdb/datasets (accessed 29 Nov 2016).

- 14. Roche JJ, Wenn RT, Sahota O, et al. Effect of comorbidities and postoperative complications on mortality after hip fracture in elderly people: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ 2005;331:1374 10.1136/bmj.38643.663843.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khan MA, Hossain FS, Ahmed I, et al. Predictors of early mortality after hip fracture surgery. Int Orthop 2013;37:2119–24. 10.1007/s00264-013-2068-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perez JV, Warwick DJ, Case CP, et al. Death after proximal femoral fracture--an autopsy study. Injury 1995;26:237–40. 10.1016/0020-1383(95)90008-L [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li Y, Glance LG, Cai X, et al. Adverse hospital events for mentally ill patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. Health Serv Res 2008;43:2239–52. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00875.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rivard PE, Elixhauser A, Christiansen CL, et al. Testing the association between patient safety indicators and hospital structural characteristics in VA and nonfederal hospitals. Med Care Res Rev 2010;67:321–41. 10.1177/1077558709347378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. ICD-10 Data. ICD10Data.com. 2017. http://www.icd10data.com/Search.aspx?search=PNEUMONIA (accessed 27 Mar 2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015368supp001.pdf (3.5MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-015368supp002.doc (108KB, doc)