Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of coronary artery disease screening in asymptomatic patients with type 2 diabetes and assess the statistical reliability of the findings.

Methods

Electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library and clinicaltrials.org) were reviewed up to July 2016. Randomised controlled trials evaluating coronary artery disease screening in asymptomatic patients with type 2 diabetes and reporting cardiovascular events and/or mortality were included. Data were summarised with Mantel-Haenszel relative risk. Trial sequential analysis (TSA) was used to evaluate the optimal sample size to detect a 40% reduction in outcomes. Main outcomes were all-cause mortality and cardiac events (non-fatal myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death); secondary outcomes were non-fatal myocardial infarction, myocardial revascularisations and heart failure.

Results

One hundred thirty-five references were identified and 5 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria and totalised 3315 patients, 117 all-cause deaths and 100 cardiac events. Screening for coronary artery disease was not associated with decrease in risk for all-cause deaths (RR 0.95(95% CI 0.66 to 1.35)) or cardiac events (RR 0.72(95% CI 0.49 to 1.06)). TSA shows that futility boundaries were reached for all-cause mortality and a relative risk reduction of 40% between treatments could be discarded. However, there is not enough information for firm conclusions for cardiac events. For secondary outcomes no benefit or harm was identified; optimal sample sizes were not reached.

Conclusion

Current available data do not support screening for coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes for preventing fatal events. Further studies are needed to assess the effects on cardiac events.

PROSPERO

CRD42015026627.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease screening, type 2 diabetes, systematic review, meta-analysis, trial sequential analysis

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Electronic databases were reviewed to identify randomised controlled trials evaluating screening for coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes.

Results from individual studies were combined and summarised with Mantel-Haenszel relative risk.

Trial sequential analysis was used to assess the optimal sample size for the outcomes.

The results should be interpreted with caution as different screening methods were combined.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a well-known risk factor for atherosclerosis and asymptomatic coronary disease is frequent and associated with increased mortality.1 Intensive medical treatment with antiplatelet agents, statins, as well as blood pressure and glycaemic control decrease the number of cardiovascular events in patients with established coronary artery disease.2 It is expected that early detection and treatment of myocardial ischaemia would lead to similar benefits.

Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) reduces mortality by 40% in patients with diabetes and established multivessel coronary disease.3 However, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) does not appear to influence mortality in patients with asymptomatic and stable coronary artery disease (with or without diabetes) when compared with intensive medical therapy alone.4 BARI 2D (Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes) study results showed no benefit of early revascularisation in patients with type 2 diabetes. On the other hand, it suggested that CABG might be better than medical therapy alone, but this finding must be interpreted with caution, as the allocation to PCI or CABG was not randomised.5 Moreover, patients with diabetes and high-risk coronary lesions do benefit from CABG.3 In summary, the goal of a screening strategy for coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes would be the identification of subjects with high-risk coronary lesions (multivessel), who would be eligible for CABG and might benefit from this intervention by reducing coronary events and mortality.

Some trials directly evaluated the effects of screening for coronary artery disease versus usual care and found no benefit for mortality or coronary events.6 7 These trials were performed with adequate designs but in most cases have limited conclusions due to lack of power.6 7 Meta-analysis is a valuable tool in this situation, as it combines studies in a single analysis, which increases the sample size. Furthermore, trial sequential analysis (TSA) enables the assessment of sample size power and the need for further studies.8 9

Therefore, our objective was to assess the efficacy of screening for asymptomatic coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes compared with no screening in reducing cardiac events (non-fatal myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality) and all-cause mortality. Furthermore, we aimed to evaluate the statistical reliability (sample size power) of the results.

Research design and methods

This study follows the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analysis.10 The present review was registered in the PROSPERO registry no. CRD42015026627.

Search strategy

To perform the present study, we searched for randomised controlled trials evaluating the effects of screening for coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes reporting any of the outcomes of interest, which were non-fatal myocardial infarction, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, myocardial revascularisations and heart failure events. PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library and clinicaltrials.org databases were searched from inception through July 2016 using the following terms: type 2 diabetes, screening of coronary heart disease and randomised clinical trial. No restrictions were made regarding study length, publication year or language. The full search terms for PubMed were: (screening AND coronary artery disease) AND (randomized controlled trial[Publication Type] OR randomized[Title/Abstract] OR placebo[Title/Abstract]) AND ‘Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2’[Mesh]. We also searched the references lists of main publications on the topic manually.

Study selection

Two authors (DVR and LCP) performed the study selection independently. We included any randomised controlled trial which included patients with type 2 diabetes and that evaluated the effects of any coronary artery disease screening method on the incidence of non-fatal myocardial infarction, cardiovascular or all-cause mortality. We excluded studies that were not randomised and that compared two different screening methods. Initially, titles and abstracts were reviewed for potentially eligible studies. These studies were then evaluated in full text and those reporting any of the selected outcomes were considered for the final review and meta-analysis.

Data extraction

The following information was extracted with a standardised form: first author’s name; study name and year of publication; screening method; study registry; baseline HbA1c and age; number of men; number of patients in each group; follow-up time; number of events: non-fatal myocardial infarction, cardiovascular and all-cause deaths, revascularisations and heart failure events. We defined cardiac events as a composite of non-fatal myocardial infarctions and cardiovascular deaths.

Appraisal of study quality

We evaluated the risk of bias at the study level with the Cochrane Collaboration tool11; for the ‘other bias’ item we evaluated the presence of a trial registry as low risk of bias and lack of registry as high risk. We defined no prespecified analysis based on the risk of bias of the individual studies. The overall quality of the evidence of each meta-analysis was classified as ‘high,’ ‘moderate,’ ‘low’ or ‘very low’ based on the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE).12

Data analysis

The outcomes of interest were summarised as relative risk (RR) of screening versus no screening and they were combined using the Mantel-Haenszel RR. The heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 tests (I2>50% indicating high heterogeneity).

One of the aims of our study was to assess the reliability of the results—that is, to evaluate the ideal sample size to establish firm conclusions about the findings.9 To accomplish this, we performed TSA of the data. Interim analysis of a single randomised trial avoids type I error by creating monitoring boundaries for an estimated difference between groups, so if the estimated difference is reached the trial could be terminated. TSA uses a similar accurate method to create monitoring boundaries and estimate the optimal sample size in meta-analyses.8 9 TSA performs a cumulative meta-analysis with the results of the available studies (represented by the Z-curve): as each new study is included, significance is tested and CIs are estimated. It also creates adjusted boundaries for benefit, harm, and futility, and estimates the optimal sample size for a given difference between treatment arms, so that a smaller estimated difference would result in wider boundaries and a greater optimal sample size.8 Because cumulative meta-analyses may lead to false-positive results due to repetitive testing, this evaluation is adjusted to control for repeated analyses, while maintaining type I error at 5% and the power at 80%.8 It is also adjusted for the variability between trials and for the amount of available evidence. If one of the boundaries (benefit, risk or futility) or if the optimal sample size is reached, firm conclusions might be made (for that predefined difference) and further studies are deemed unnecessary; instead, if no boundaries are reached, further studies are needed to settle the question.8 For the present analysis, we performed a TSA for a relative difference (relative risk reduction—RRR) between groups of 40% and considered as control group event rate the incidence observed in the control group for each outcome. The RRR value was chosen based on the expected benefit of revascularisation in the mortality rate demonstrated by previous studies.3 An additional TSA analysis was also performed using a RRR of 20%.

The risk of bias graph was generated with RevMan software V.5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). The meta-analyses were performed with Stata V.12.0 and the TSA and graphics were generated using TSA software V.0.9 [beta] (Copenhagen Trial Unit, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Results

The search in electronic databases and the manual review retrieved 135 studies for the evaluation of titles and abstracts. After screening, seven studies were evaluated in full text and five fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria.6 7 13–15 The study flow chart is depicted in online supplementary figure 1.

bmjopen-2016-015089supp001.pdf (397.5KB, pdf)

The included studies comprised patients with a mean age of 61 years, with a mean HbA1c of 7.6% and the mean follow-up was 4.1 years. Additional characteristics are presented in table 1. Most studies performed screening with stress testing along with electrocardiography, echocardiography or scintigraphy monitoring; one study performed coronary CT angiography with measurement of coronary calcium. The studies totalised 3315 patients with 117 all-cause deaths and 100 cardiac events.

Table 1.

Included study characteristics

| Study name | First author | Publication year | Screening method | Management recommendation | Patients (n) | Age (years) | HbA1c (%) | Blood pressure (mmHg) | Smoking (%) | Statin use (%) | Aspirin use (%) | Mean follow-up (years) | Registry |

| – | Faglia et al 13 | 2005 | Exercise ECG and stress echocardiography | Yes | 71 | 58.7±8.3 | 8.6±2.3 | 143/85 | 46 | 28 | 9 | 4.4 | No |

| No screening | No | 70 | 61.5±8.1 | 8.4±1.9 | 141/84 | 55 | 21 | 12 | |||||

| DIAD | Young et al 7 | 2009 | Stress scintigraphy | No | 561 | 60.7±6.7 | 7.2±1.6 | 133/80 | 10 | 37 | 43 | 4.8 | Yes |

| No screening | No | 562 | 60.8±6.4 | 7±1.5 | 132/79 | 9 | 41 | 46 | |||||

| DYNAMIT | Lièvre et al 14 | 2011 | Bicycle exercise test or stress scintigraphy | No | 316 | 64.1±6.4 | 8.6±2.2 | NR | 17 | 33 | 39 | 3.5 | Yes |

| No screening | No | 315 | 63.7±6.4 | 8.7±2 | NR | 14 | 36 | 24 | |||||

| FACTOR-64 | Muhlestein et al 6 | 2014 | Coronary CT angiography | Yes | 452 | 61.5±7.9 | 7.4±1.4 | 129/74 | 16 | 76 | 43 | 4.0 | Yes |

| No screening | No | 448 | 61.6±8.3 | 7.5±1.4 | 130/74 | 15 | 72 | 40 | |||||

| DADDY-D | Turrini et al 15 | 2015 | Exercise ECG | Yes | 262 | 61.9±4.8 | 7.7±1.4 | 140/81 | 40 | 39 | 29 | 3.6 | Yes |

| No screening | No | 258 | 62±5.1 | 7.8±1.3 | 141/81 | 37 | 44 | 25 |

NR, not reported

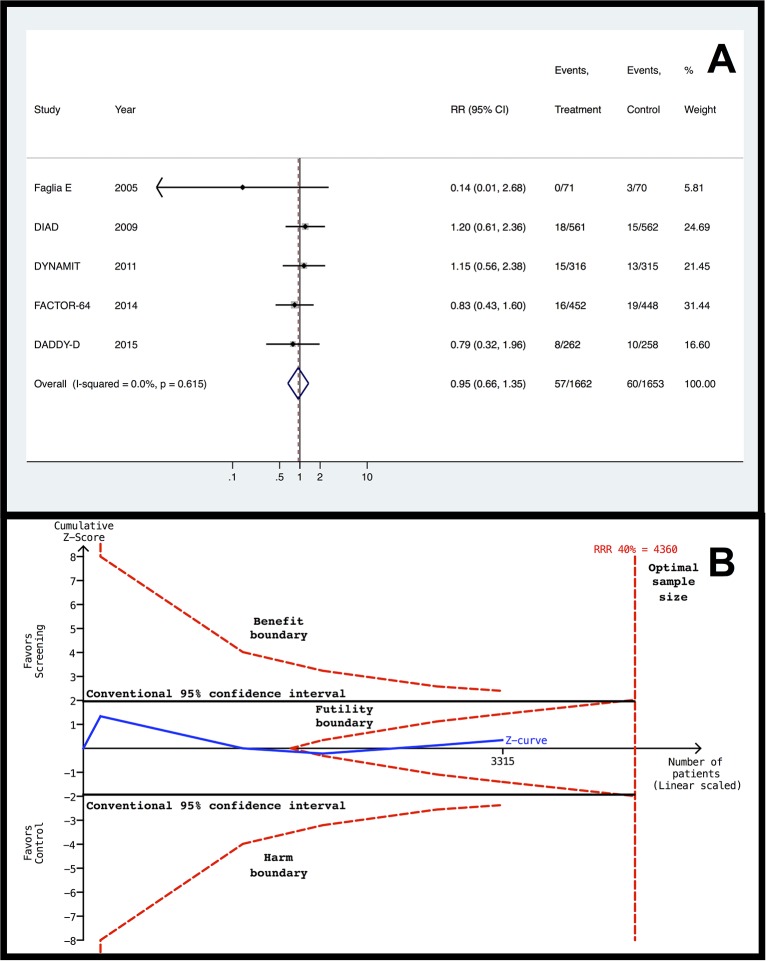

Data showed no difference between patients in coronary artery disease screening and control groups for all-cause death incidence (figure 1A): RR 0.95 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.35). There was low heterogeneity (I2=0% and p=0.615). TSA for all-cause mortality events indicates that the futility boundary was reached, so a difference of 40% between groups is firmly discarded and no further studies are required (figure 1B). For the RRR of 20%, neither the optimal sample size (19 548 patients) nor the futility boundary was reached.

Figure 1.

Forest plot and TSA of screening versus no screening for all-cause mortality outcome. (A) Forest plot for all-cause mortality. (B) TSA for a relative risk reduction of 40%. The continuous blue line represents the Z line (cumulative effect size), red dashed lines represent the harm, benefit, and futility boundaries, and the estimated optimal sample size adjusted to sample size and repeated analysis. The continuous black lines represent the conventional CIs. RR, relative risk; RRR, relative risk reduction; TSA, trial sequential analysis.

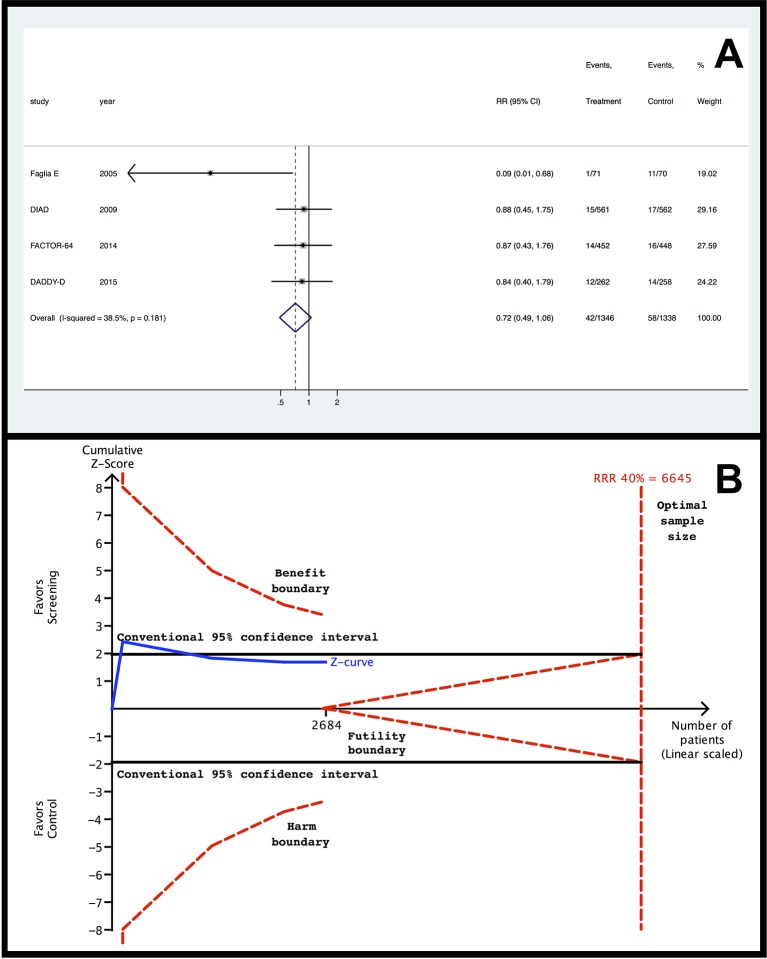

There was also no difference in cardiac events (figure 2A): RR 0.72 (95% CI 0.49 to 1.06; I2=38.5% and p=0.181). For this outcome, TSA shows that the optimal sample size is 6645 patients, which is larger than the current sample. Furthermore, neither the benefit nor the futility boundaries were reached (figure 2B). The analysis with the RRR of 20% showed similar results, but with a much larger optimal sample size (29 763 patients).

Figure 2.

Forest plot and TSA of screening versus no screening for cardiac events outcome. (A) Forest plot for cardiac events. (B) TSA for a relative risk reduction of 40%. The continuous blue line represents the Z line (cumulative effect size), red dashed lines represent the harm, benefit, and futility boundaries, and the estimated optimal sample size adjusted to sample size and repeated analysis. The continuous black lines represent the conventional CIs. RR, relative risk; RRR, relative risk reduction; TSA, trial sequential analysis.

Additional outcome analyses are presented in table 2: the coronary artery disease screening group was similar to the control group for non-fatal myocardial infarction (RR 0.65 (95% CI 0.41 to 1.02)), heart failure (RR 0.60 (95% CI 0.33 to 1.10)) and myocardial revascularisations (PCI and CABG) (RR 1.08 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.41)). None of these outcomes reached the optimal sample size or the boundaries for futility.

Table 2.

Results for myocardial infarction, revascularisation and heart failure of screening versus no screening

| Outcome | RR (95% CI) | Accrued population | Optimal sample size (RRR=40%) | Optimal sample size (RRR=20%) |

| Non-fatal myocardial infarction | 0.65 (0.41 to 1.02) | 3315 | 6154 | 17 495 |

| Heart failure | 0.60 (0.33 to 1.10) | 3174 | 10 990 | 49 352 |

| Revascularisations | 1.08 (0.83 to 1.41) | 3174 | 10 598 | 47 339 |

RR, relative risk; RRR, relative risk reduction.

Overall, the study quality was high according to the Cochrane Collaboration tool (online supplementary figures 2 and 3).11 It must be stressed that none of the studies was blinded, but this was not considered a limitation because blinding of participants (patients and clinicians) was not feasible due to the type of intervention (screening). On the other hand, blinding of outcome assessment was reported in only one study. According to GRADE,16 quality of evidence was judged as high quality for both main outcomes (all-cause mortality and cardiac events).

Discussion

In the present study we identified no benefit of screening for asymptomatic coronary artery disease for all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes. This conclusion is supported by a sufficient number of patients, as shown by TSA. Although we found no benefit for the other outcomes evaluated, such as cardiovascular events, these results are not definitive, as they are not supported by an adequate number of patients. This review shows that further studies evaluating coronary artery disease screening in type 2 diabetes are required before definitive recommendations on this topic can be made.

A relevant point of our analysis is the trend for statistically significant difference found in cardiac events and non-fatal myocardial infarction favouring the screening group. This finding seems to be driven by the study of Faglia et al,13 which was the smallest and oldest study included in our analysis. Moreover, patients in this study had an unfavourable clinical profile, represented by the worst glycaemic control, the highest blood pressure, the greatest prevalence of smoking, and the lowest use of statins and aspirin in comparison with the other studies. Despite this trend, TSA shows that there are insufficient data to perform firm conclusion about cardiac events and myocardial infarction. Therefore, further studies are needed to investigate the effects of screening for coronary artery disease in these outcomes.

Some limitations of this review must be acknowledged. First, the trials performed different screening tests with different specificity and sensitivity.2 This generates two potential problems: studies using technics with lower accuracy might compromise the benefit of other technics, and combining these different tests may be questionable. Despite this, current guidelines do not define a preferable strategy for the diagnosis of coronary artery disease,2 and a clinical trial supports this position.17 Therefore, we believe these tests may be aggregated in a meta-analysis, as they all aim to identify high-risk patients with greater chance to benefit from CABG.3 5 18 We cannot rule out the possibility that a test with higher sensitivity (coronary CT angiography)19 would be beneficial.2 However the individual results of the FACTOR-64 which used a highly accurate method do not support this conclusion,6 and, as discussed above, the potential benefit we identified in this review seems to be derived from only one study13 that used tests with low to moderate sensitivity.

The second limitation was the somewhat choice of a relative difference of 40% between treatment arms. It was based on the benefits of CABG for patients with severe coronary artery disease.3 Even though this evidence was published in the 1990s, it is still largely used by guidelines to recommend revascularisation for stable coronary artery disease. In addition, recent studies and meta-analysis have shown that CABG is superior to PCI for subjects with or without diabetes and multivessel coronary disease.5 18 20 As only CABG is capable to reduce mortality and major cardiac events, a screening intervention aimed to identify patients with multivessel coronary artery disease assumes that patients would benefit from CABG. Therefore, a clear clinical benefit must be evident to justify the risks and costs from screening and the potential procedures resulting from it.

The analysis with a RRR of 20% showed that for cardiac events, myocardial infarction, heart failure and revascularisations, the results from TSA also showed that the number of patients included was not enough. In addition, for all-cause mortality the RRR of 20% analysis also lacked power and it would require an increase in the number of patients by a factor of 5, which is unlikely to happen.

Another potential source for heterogeneity in our study is the inclusion of patients with different basal cardiovascular risk due to comorbidities and risk factors. As discussed above, this might be the case of Faglia et al’s study,13 which had older patients with an unfavourable clinical profile and found reduced risk of myocardial screening with the screening. Due to the limited number of studies, subgroup analyses could not be performed. FACTOR-64 study included some patients with type 1 diabetes,6 but this seems a minor issue, as they represent only 10% of the sample in the original study, and 3% of the systematic review sample. Finally, the results of this systematic review are restricted to patients with characteristics comparable to the included patients in the individual studies. So these conclusions are not applicable to some higher risk populations, such as patients with chronic kidney injury.

Some strengths of our study must be pointed out. We performed a comprehensive database search and identified all randomised trials evaluating the effects of a screening strategy for coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, the trials included are of high quality. As mentioned, there are some methodological differences between the studies, but the statistical heterogeneity was low or absent in the analyses. We also performed detailed analyses of the data and through TSA we could discard a significant difference between treatment arms for all-cause mortality. Unfortunately, we cannot make the same firm conclusions for the cardiac events, myocardial infarction, heart failure and revascularisation outcomes.

In conclusion, the present study supports the idea that patients with type 2 diabetes without symptoms of coronary artery disease do not need to be screened for asymptomatic disease and that non-invasive coronary examinations should be reserved for symptomatic patients. This would avoid unnecessary risks, patient distress and costs for asymptomatic patients. For other events new studies are still needed before definitive recommendations can be made.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Fabrizio Turrini for sharing additional data on his study (DADDY-D study).

Footnotes

Contributors: The criteria from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors for authorship were followed and the final version of the manuscript has been approved for submission by all authors. This manuscript has not been published before, and is not being considered for publication in any other journal. DVR was responsible for study design, data acquisition, analysis, interpretation and drafting of the manuscript. LCP contributed to study design, reference selection, and data acquisition and analysis. CBL and JLG contributed to study design, data analysis and interpretation, and drafting of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Drs DVR and JLG are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: This study was funded by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and the Fundo de Incentivo à Pesquisa e Eventos from Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre. Support for the publication fee was provided. CNPq had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the extraction, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare that no support was received from any organization for the submitted work; JLG reports grants from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico during the conduct of the study; grants and others from Eli Lilly, grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, grants and others from Boehringer Ingelheim, grants from GlaxoSmithKline, grants and others from Novo Nordisk, grants from Janssen, outside the submitted work; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work are reported.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All available data is presented in current report, no additional data available.

References

- 1. Rajagopalan N, Miller TD, Hodge DO, et al. . Identifying high-risk asymptomatic diabetic patients who are candidates for screening stress single-photon emission computed tomography imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005;45:43–9. 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.06.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. . 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2012;126:e354–471. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318277d6a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yusuf S, Zucker D, Peduzzi P, et al. . Effect of coronary artery bypass graft surgery on survival: overview of 10-year results from randomised trials by the coronary artery bypass graft surgery Trialists Collaboration. Lancet 1994;344:563–70. 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)91963-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sedlis SP, Hartigan PM, Teo KK, et al. . Effect of PCI on Long-Term Survival in patients with stable ischemic Heart Disease. N Engl J Med 2015;373 46:1937–46. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Frye RL, August P, Brooks MM, et al. . A randomized trial of therapies for type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2009;360 15:2503 10.1056/NEJMoa0805796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Muhlestein JB, Lappé DL, Lima JA, et al. . Effect of screening for coronary artery disease using CT angiography on mortality and cardiac events in high-risk patients with diabetes: the FACTOR-64 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312:2234–43. 10.1001/jama.2014.15825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Young LH, Wackers FJ, Chyun DA, et al. . Cardiac outcomes after screening for asymptomatic coronary artery disease in patients with type 2 diabetes: the DIAD study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2009;301:1547–55. 10.1001/jama.2009.476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Thorlund K, Engstrøm J, Wetterslev J, et al. . User manual for Trial Sequential analysis (TSA). Copenhagen, Denmark: Copenhagen Trial Unit, Centre for Clinical Intervention Research; 2011:1–115. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wetterslev J, Thorlund K, Brok J, et al. . Trial sequential analysis may establish when firm evidence is reached in cumulative meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 2008;61:64–75. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009;339:b2535 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. . The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011;343:d5928 10.1136/bmj.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schünemann HJ, Schünemann AH, Oxman AD, Brozek J, et al. . Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ 2008;336:1106–10. 10.1136/bmj.39500.677199.AE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Faglia E, Manuela M, Antonella Q, et al. . Risk reduction of cardiac events by screening of unknown asymptomatic coronary artery disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus at high cardiovascular risk: an open-label randomized pilot study. Am Heart J 2005;149:e1–e6. 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lièvre MM, Moulin P, Thivolet C, et al. . Detection of silent myocardial ischemia in asymptomatic patients with diabetes: results of a randomized trial and meta-analysis assessing the effectiveness of systematic screening. Trials 2011;12:23 10.1186/1745-6215-12-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Turrini F, Scarlini S, Mannucci C, et al. . Does Coronary Atherosclerosis Deserve to be diagnosed earlY in Diabetic patients? the DADDY-D trial. screening Diabetic patients for Unknown Coronary disease. Eur J Intern Med 2015;26:407–13. 10.1016/j.ejim.2015.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. . Incorporating considerations of resources use into grading recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:1170–3. 10.1136/bmj.39504.506319.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Douglas PS, Hoffmann U, Patel MR, et al. . Outcomes of anatomical versus functional testing for coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2015;372 300:1291–300. 10.1056/NEJMoa1415516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Farkouh ME, Domanski M, Sleeper LA, et al. . Strategies for multivessel revascularization in patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med 2012;367 84:2375–84. 10.1056/NEJMoa1211585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Celeng C, Maurovich-Horvat P, Ghoshhajra BB, et al. . Prognostic Value of Coronary Computed Tomography Angiography in Patients with Diabetes: a Meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2016;39:1274–80. 10.2337/dc16-0281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sipahi I, Akay MH, Dagdelen S, et al. . Coronary artery bypass grafting vs percutaneous coronary intervention and long-term mortality and morbidity in multivessel disease: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of the arterial grafting and stenting era. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:223–30. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12844 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015089supp001.pdf (397.5KB, pdf)