Abstract

Background

Epidemiology of Neisseria meningitidis has been changing since the introduction of universal vaccination programmes against meningococcal serogroup C (MenC) and meningococcal serogroup B (MenB) has now become dominant. This study aimed to analyse the cases reported in institutional data recording systems to estimate the burden of invasive meningococcal diseases (IMDs) and assess the effectiveness of surveillance in Veneto region (Italy).

Methods

Analysis was performed from 2007 to 2014 on data recorded in different systems: Mandatory Notification System, National Surveillance of Invasive Bacterial Diseases System and Laboratories Surveillance System (LSS), which were pooled into a combined surveillance system (CSS) and hospital discharge records (HDRs). A capture-recapture method was used and completeness of each source estimated. Number of cases with IMD by source of information and year, incidence of IMD by age group, case fatality rate (CFR) and distribution of meningococcal serogroups by year were also analysed.

Results

Combining the four data systems enabled the identification of 179 confirmed cases with IMD, achieving an overall sensitivity of 94.7% (95% CI: 90.8% to 98.8%), while it was 76.7% (95% CI: 73.6% to 80.1%) for CSS and 77.2% (95% CI: 74.1% to 80.6%) for HDRs. Typing of isolates was done in 80% of cases, and 95.2% of the typed cases were provided by LSS. Serogroup B was confirmed in 50.3% of cases. The estimated IMD notification rate (cases with IMD diagnosed and reported to the surveillance systems) was 0.48/100 000 population, and incidence peaked at 6.2/100 000 in children aged <1 year old (60.9% due to MenB), and increased slightly in the age group between 15 and 19 years (1.1/100 000). A CFR of 14% was recorded (8.7% in paediatric age).

Conclusions

Quality of surveillance systems relies on case ascertainment based on serological characterisation of the circulating strains by microbiology laboratories. All available sources should be routinely combined to improve the epidemiology of IMD and the information used by public health departments to conduct timely preventive measures.

Keywords: meningococcal disease, surveillance systems, sensitivity, laboratory surveillance data

Strengths and limitations of this study.

In this study, a record linkage analysis on several different surveillance systems showed that the quality of epidemiological information on invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) can be improved by integrating it with specific microbiological laboratory-based data.

Our results suggest that a routine pooling of all available data sources is needed to overcome any surveillance gaps. This approach is recommended in order to provide guidance for decision-makers on crucial public health policies and achieve an effective control of meningococcal disease.

Our analysis also indicates that microbiological data are suboptimally recorded by conventional surveillance systems. For this reason, the availability of data generated by laboratories is crucial for clarifying the temporal and spatial distribution of the circulating meningococcal serogroups.

To provide a complete surveillance assessment, our investigation requires a more in depth analysis of supplementary data sources so that some clearer trends can be detected (ie, vaccination status or surveillance of vaccine failure, as well as antibiotic resistance).

Introduction

Neisseria meningitidis is the organism responsible for invasive meningococcal diseases (IMD) worldwide. IMD can affect all ages and have numerous serious manifestations, the most common being meningitis, septicaemia or a combination of the two.1

Of all N. meningitidis serogroups identified, five are the most often responsible for IMD (serogroups A, B, C, Y and W), but the epidemiology of IMD varies around the world and different geographical areas are classified as having a low, moderate or high endemicity.2 3 In Europe, the notification rate of cases with confirmed IMD is 0.75/100 000 population (range: 0.09–1.99/100 000 population). During the period 2008–2012, the European Centre for Disease Control included Italy among the European countries with a low incidence of IMD, given its notification rate of 0.26/100 000 population.4

The distribution of the meningococcal serogroups varies considerably, both geographically and temporally, around the world. Meningococcal serogroup B (MenB) dominates in many parts of the world, including Europe, and the inclusion of a conjugated vaccine for meningococcal serogroup C (MenC) in the routine vaccination programmes of several European countries has led to a drastic reduction in the cases of IMD caused by MenC, leaving the countries concerned with a predominance of IMD due to MenB.1

Aside from MenB and MenC, other serogroups (A, Y and W) are still important in areas of Europe and close to its borders, and they can be responsible for epidemic disease.5 Recent evidence indicates that meningococcal serogroup Y (MenY) has continued to increase in northern Europe and the proportion of IMD attributable to MenY remains high in Scandinavian countries, ranging from 26% to 51%.6

An analysis of consolidated data (referring to 2014) shows that the incidence of IMD in Italy has remained stable in recent years, apart from an unexpected increase in the cases of MenC in young adults was reported in 2015 due to a cluster in Tuscany, which recurred in the early months of 2016. Immunisation campaigns have been implemented as a result, continuously adapting them to the evolution of the epidemiological situation, and IMD surveillance activities have been enhanced.7 MenC is the second most common serogroup in Italy (accounting for 31% of the 115 cases with a known serogroup in 2014) after MenB (with 48% of the 115 cases in 2014), while MenY is the third cause of meningococcal infection (13% of the serogroups typed in 2014).8

Based on 2014 data, in Veneto (northeast Italy) the incidence of IMD is 0.35/100 000 population. The introduction of a universal free infant vaccination programme against MenC has changed the local epidemiology, making MenB dominant instead of MenC.9

Surveillance data can provide information on the frequency of IMD and the distribution of the circulating serogroups (on which vaccination programs are based). In times when the incidence of these diseases is declining, a complete and timely reporting of cases of infection is essential for prompt and effective clinical and public health interventions, and for epidemiological investigations, postexposure prophylaxis, and any vaccination of members of households in the case of individuals infected by a vaccine-preventable serogroup.10 11

However, the real burden of IMD is not known for many parts of the world due to inadequate epidemiological surveillance schemes.12 This paper analysed the cases reported in the various institutional public health data recording systems in order to: assess the outcome of action taken to monitor invasive meningococcal infection in the Veneto region of northeastern Italy; estimate the incidence of IMD; establish the distribution of the circulating meningococcal serogroups and test the completeness of the different sources considered.

Materials and methods

We considered the data available from four different data sources in Veneto on the surveillance of invasive bacterial diseases over the years from 2007 to 2014.

The cases considered in our analysis were all laboratory-confirmed, that is, they involved individuals meeting the laboratory criteria with at least one of the following: isolation of N. meningitidis from a normally sterile site, including purpuric skin lesions; detection of N. meningitidis nucleic acid from a normally sterile site, including purpuric skin lesions; detection of N. meningitidis antigen in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and detection of Gram-negative-stained diplococcus in CSF.13

The different data systems analysed were the following:

the Mandatory Notification System (MNS) of the Italian Ministry of Health; physicians are obliged to report all cases of invasive meningococcal infection to the National Health Service within 24 hours and, after being confirmed, cases are documented in the surveillance system. The MNS database contains a unique patient identification number, demographic details and the dates of notification, first symptoms and diagnosis.

The National Surveillance of Invasive Bacterial Diseases System (NSS) was implemented in 1994 by the Istituto Superiore di Sanità (ISS) to collect data on Neisseria causing IMD. Hospital physicians report cases to their local Public Health Unit. The NSS contains a unique patient identification number, demographic details, the name of the laboratory submitting the strain, the dates of sample collection and receipt and the outcome of N. meningitidis typing.

The Laboratories Surveillance System (LSS) was extended to cover all invasive bacterial diseases (including those due to N. meningitidis) in Veneto in 2007; it is based on data collected by hospital and Local Health Authority microbiology laboratories. The microbiology laboratorians report all suspected clinical cases of IMD to the Regional Epidemiology Centre and concurrently send biological samples to the Regional Reference Laboratory for culture confirmation and serotyping of the isolates.

The records of these three data sources were linked after constructing an unequivocal personal code (patient’s date of birth, gender, post al code/place of residence and initials). All further linkages were checked manually and, if plausible for all variables, they were assumed to be correct and recorded routinely in a single database, the combined surveillance system (CSS).

As a fourth data source, we considered the regional archives of hospital discharge records (HDRs), identifying all hospital stays that contained a principal and/or secondary diagnosis coded as 036.xx (meningococcal infection) according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification.

A capture-recapture method, as described by De Greeff et al, was used and certain crucial assumptions were made.14 First, a patient listed in both the CSS and the HDR databases had to be matched as one and the same patient; second, the same population and time period had to be covered by the databases; third, reports of all data sources must be made independently and last, all cases had to have an equal probability of being selected in a given source.14–16 The contribution of the single data sources was also assessed.

The first step of the capture-recapture analysis involved analysing the MNS, NSS and LSS data to estimate the number of cases not registered, and thereby obtain the total number of cases of IMD based on the degree of overlap between the different sources. The models were compared with the likelihood ratio test (G2), the Akaike Information Criterion [AIC=G2–2(df)] and the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The best-fitting model was selected from among eight different log-linear models, choosing the one with the lowest G2 and AIC.14 After constructing the CSS, the second step involved applying the capture-recapture method to the CSS and the HDRs to compare the completeness of Veneto’s routine data collection system with that of the hospitalisation rate for specific meningococcal diseases. The completeness (as a percentage) of each data source was estimated by dividing the number of cases of meningococcal disease observed for each source by the number of cases resulting from the capture-recapture estimate. The incidence of IMD (per 100 000 population) was estimated considering the number of confirmed cases as a proportion of the region’s resident population (provided by the Veneto Regional Authority’s statistics office). The number of IMD-related deaths was obtained from the data available for this study (all sources) and the case fatality rate (CFR) was calculated. The distribution of the cases of IMD by serogroup was assessed by analysing the CCS data alone.

This study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and with Italian privacy law (Legislative decree no 196/2003) on the protection of personal data. Informed consent and approval from the local ethics committee were unnecessary because the information involved is routinely recorded for surveillance purposes and treated in anonymous form. Moreover, resolution no 85/2012 of the Italian Guarantor on the protection of personal data allows for personal data to be processed for the purposes of medical, biomedical and epidemiological research, and confirms that data on people’s state of health may be used in aggregate form in scientific studies.13 17

Results

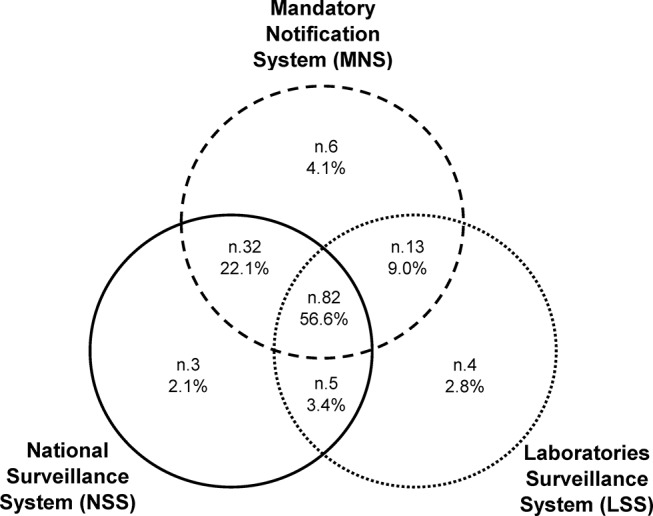

During the interval between 2007 and 2014, there were 133 cases of IMD notified to the MNS, 122 to the NSS and 104 to the LSS. Combining the three surveillance systems (CSS) identified 145 cases recorded in at least one of the three sources, and 56.6% (of them 82/145) were listed in all three (figure 1). All patients identified by the surveillance systems had been hospitalised.

Figure 1.

Venn diagram showing the number and percentage of cases of invasive meningococcal disease identified by three sources: the Mandatory Notification System, the National Surveillance of Invasive Bacterial Diseases System and the Laboratories Surveillance System in Veneto from 2007 to 2014.

The log-linear model with the lowest G2, AIC and BIC included the interaction between the MNS, NSS and LSS sources, and estimated a total of 146 (95% CI: 145 to 152) cases of IMD (table 1). The completeness of the CSS was estimated at 99.3% (95% CI: 95.4% to 100%), while for the MNS it was 91.1% (95% CI: 87.5% to 91.7%), which was >83.5% obtained for the NSS (95% CI: 80.3% to 84.1%) or the 71.2% for the LSS (95% CI: 68.4% to 71.7%).

Table 1.

Log-linear models fitted to three sources of data on invasive meningococcal disease and the estimated number of meningococcal cases in Veneto (2007-2014)

| Model | df | G2 | p-Value | AIC | BIC | x^ | N^ | 95% CI |

| A B C | 3 | 4.43 | 0.22 | −1.57 | −1.41 | 0 | 145 | 145 to 148 |

| A B C (AB) | 4 | 0.38 | 0.83 | −3.62 | −3.52 | 1 | 146 | 145 to 152 |

| A B C (AC) | 4 | 4.43 | 0.11 | 0.43 | 0.54 | 0 | 145 | 145 to 149 |

| A B C (BC) | 4 | 4.42 | 0.11 | 0.42 | 0.53 | 0 | 145 | 145 to 148 |

| A B C (AB) (AC) | 5 | 0.1 | 0.76 | −1.9 | −1.85 | 2 | 147 | 145 to 159 |

| A B C (AB) (BC) | 5 | 0.31 | 0.58 | −1.69 | −1.64 | 1 | 146 | 145 to 154 |

| A B C (AC) (BC) | 5 | 4.42 | 0.04 | 2.42 | 2.48 | 0 | 145 | 145 to 149 |

| A B C (AB) (AC) (BC) | 6 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 147 | 145 to 167 |

A, Mandatory Notification System; AIC, Akaike Information Criterion; B, National Surveillance of Invasive Bacterial Diseases System; BIC, Bayesian Information Criterion; C, Laboratories Surveillance System; G2, likelihood ratio test statistic; N^: estimate of the total cases; x^, estimate of the total cases not reported to any source. Bold values indicate the best-fitting model.

Our record-linkage analysis between the CSS and HDR data identified 179 cases of invasive bacterial disease with a specific diagnosis of N. meningitidis. Altogether, 112 cases (62.6%) were recorded by both information sources, 33 (18.4%) only by the CSS and 34 (19.0%) only in the HDRs. Capture-recapture analysis estimated 189 cases, calculating a completeness of 94.7% (95% CI: 90.8% to 98.8%) for the CSS and HDRs combined, while the two sources separately reached figures of 76.7% (95% CI: 73.6% to 80.1%) for the CSS and 77.2% (95% CI: 74.1% to 80.6%) for the HDRs.

The 33 cases emerging from the CSS, but not from the single databases (MNS, NSS and LSS), were also found in the HDRs, but without any indication of a principal or secondary diagnosis of meningococcal disease. The contribution of the CSS alone increased during the period of observation, rising from 7.5% in 2007 to 38.9% in 2014.

All N. meningitidis were laboratory-confirmed, but the serogroup was only typed in 80.0% of cases (116/145). The serogroup was available for 95.2% of the cases recorded in the LSS (99/104), while five meningococcal strains were found to be non-vital. The serogroup was also available for 41.5% (17/41) of the cases with IMD identified by the MNS and NSS surveillance systems.

Altogether, 50.3% (73/145) of the cases identified by the CSS were confirmed as MenB, 18.6% (27/145) were MenC, 8.3% (12/145) were MenY/W and 2.1% (3/145) were meningococcal group A.

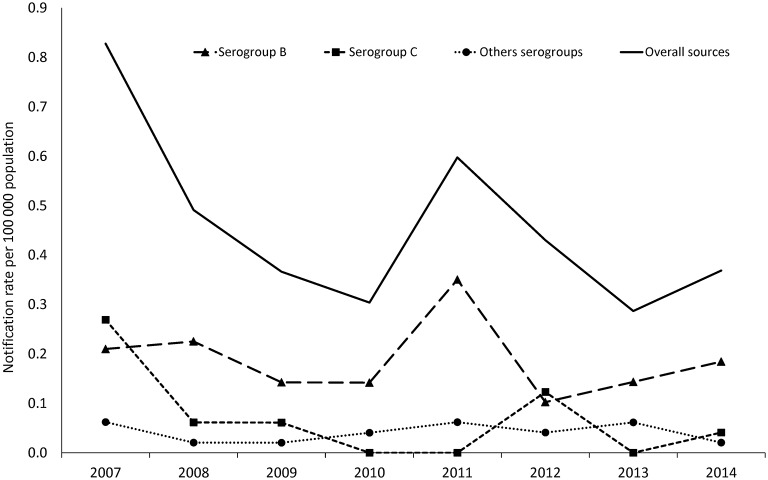

The overall notification rate for IMD was 0.48/100 000 population (the CSS accounted for 0.39/100 000). Figure 2 shows the estimated incidence of serogroups B and C, and also of the other, less common N. meningitidis serogroups (A, Y and W) isolated during the years of observation.

Figure 2.

Annual notification rate per 100 000 population for Neisseria meningitidis serogroups B and C, and the other less common serogroups (A, Y and W) in the years 2007-2014, estimated from the Combined Surveillance System.

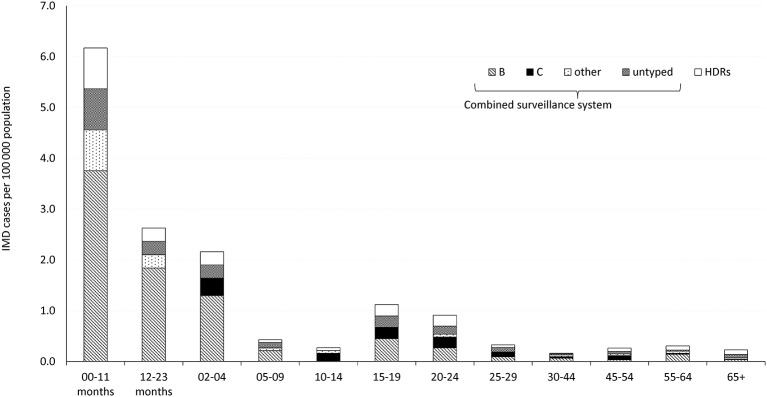

The incidence of IMD by age group, based on the cases notified, showed a peak for children <12 months old, with 6.2 cases per 100 000 population (CSS: 5.4/100 000), and a second, much smaller rise in the disease’s incidence among the age group between 15 and 19 years, with 1.1 per 100 000 population (CSS: 0.9/100 000). Among the children <12 months of age, 60.9% of the cases were attributable to MenB, with a specific rate of 3.8/100 000. Among children aged 1–4 years, the specific rate of MenB was 1.8/100 000, accounting for 70.0% of all cases. Figure 3 shows the incidence of meningococcal disease by age group and serogroup.

Figure 3.

Incidence of invasive meningococcal disease per 100 000 population by age group and serogroup in Veneto during the period 2007-2014. The data came from the three pooled sources (Combined Surveillance System) and from the hospital discharge records.

Invasive meningococcal disease proved lethal in 25 cases over the 8 years considered. The overall CFR was 14.0% and increased with age, from 8.7% in the <1 year olds to 18.4% in the >45 year olds. In the N. meningitidis serogroup, 7 of the patients who died were infected with MenC (mean age 36.6 years; range 10-72; median 33 years), 4 of them during an epidemic cluster occurring in Veneto in 2007-2008), while 12 had MenB (mean age 15.7 years; range 0-78; median 2 years), and 8 of them (67%) were children <5 years old, and a 45-year-old patient was infected with MenY. Typing was not available for the remaining five patients (20%) (mean age 64.0 years; range 20-94; median 71 years). For MenB alone, the CFR was 16.4% overall and 14.3% for infants.

Discussion

Estimating the cases of IMD with the capture-recapture method, after pooling three data sources into the CSS, gave an overall completeness of 99.3%, which became 94.7% after linkage with the HDRs. When the CSS and HDRs were considered separately, they were 76.7% and 77.2% complete, respectively. By comparison with the results of similar studies,14 15 our findings show that a greater degree of completeness was achieved by combining the CSS data with the HDRs.

A limitation of the capture/recapture method lies in the lack of a full independence between the sources that represent an assumption of the application of methodology. In our analysis of the CSS, which included data from three sources, this assumption was not crucial because interaction terms can be incorporated in the regression models to adjust for source dependence, while the two sources are independent in the two source (CSS and HDR) capture/recapture.18

Our assessment of the effectiveness of IMD surveillance in Veneto (northeastern Italy) reveals an under-reporting phenomenon, despite the clinical severity of these diseases. This goes to show that Italy’s national surveillance systems (MNS and NSS) are not always notified of every case.19

Based on the data in the national integrated surveillance systems (MNS and NSS) and the LSS, the incidence of IMD was estimated at 0.39/100 000 for the years 2007-2014. Linkage between these sources returned a higher rate than the one estimated for Italy in recent years (0.28/100 000),20 and for infants <1 year old it was 5.4/100 000, as opposed to the estimated 3.6/100 000. This discrepancy is probably attributable partly to the endemic epidemiological profile of the distribution of N. meningitidis in the geographical area considered in this study, but also to a different sensitivity of the surveillance systems in recording the total number of cases of IMD, which makes it difficult to reliably establish the burden of these diseases. Our findings show that the availability of appropriate diagnostic services (ie, microbiology laboratories) is crucial for an accurate epidemiological picture and for identifying the circulating serotypes on which to base prevention policies.

Thirty-four cases of IMD were only identifiable from the HDRs, making it seem important to use this data source to complete the epidemiological picture of IMD. The possibility of coding errors cannot be ruled out, however, so the HDR dataset can clearly be used to establish the frequency of a disease only after the data they contain have undergone critical review. For the years of our analysis (2007-2014), the HDRs containing a diagnosis of meningococcal infection identified much the same number of cases of IMD as the databases of the three surveillance systems combined. Errors relating to inappropriately recorded discharge diagnoses or misdiagnoses are more likely in the hospital records, however, whereas this was not expected in the CSS because all the cases were laboratory-confirmed.

Our findings indicate that HDRs should not be considered exhaustive as a sole source of information because they failed to identify approximately 18% of the cases of IMD. The cases recorded by the CSS concerned patients who had been admitted to hospital, and data linkage pinpointed some whose HDRs made no specific mention of meningococcal infection. There is, therefore, a need to improve the accuracy of HDR data. Another weakness of HDRs for the purpose of monitoring IMD stems from their failure to provide any information on the typing of the N. meningitidis strains, which prevents a thorough investigation into the infection’s epidemiological profile.

Judging from our data, N. meningitidis typing was done for 80.0% of the IMD isolates obtained, with an important contribution—for meningococcal surveillance purposes—coming from the LSS. In fact, typing was available for 95.2% of the cases identified by means of the LSS, as compared with 41.4% of the cases in the MNS and NSS. LSS was the system with the lowest percentage of completeness, so it is crucially important to raise the proportion of culture-confirmed cases and integrate its findings with the data from other sources.

A further contribution to clarifying the epidemiological picture of IMD can come from serotyping by real-time PCR, which is significantly more sensitive than culture and enables a diagnosis in culture-negative samples. This approach should be included in routine surveillance programs.21

From the public health standpoint, the percentage of cases missing from the CCS, despite the notification of cases of IMD being mandatory in Italy, may negatively affect the ability of the national health service to conduct epidemiological surveys and adopt appropriate preventive measures. Postexposure prophylaxis and the vaccination of people coming into contact with cases with IMD are very important. The rate of secondary disease for close contacts is highest during the first few days after the onset of the disease in the primary patient, and antimicrobial chemoprophylaxis should be administered as soon as possible (ideally within 24 hours after the case has been identified); chemoprophylaxis administered for >14 days after the onset of illness in the index case patient is probably of little or no value.22 In this setting, physicians’ reporting of suspected cases needs to be improved in order to ensure a better and more extensive public health response. Early warning systems based on emergency rooms could also be important for speeding up the identification of cases.11

To improve clinicians’ sensitivity to the need to report IMD promptly, some authors suggest using ad hoc reminders, and posting lists of diseases that should be reported and guidelines on the reporting procedures in emergency rooms.23

Isolate analysis indicated that MenB was the organism most often responsible for IMD in our sample, especially among children <1 year old. We identified a reduction in the number of cases involving MenC, and this is probably related to the high vaccination coverage rate achieved in this region.24

Meningococcal C vaccination was introduced in Veneto in 2008, actively inviting age cohorts at 13 months, 6 years and 15 years old, and reaching a coverage of about 90.0% since 2010.24 To further improve the programme, a multicomponent vaccine against MenB was introduced in 2015, and infants were actively invited, but coverage data are not yet available. Further analyses are needed to assess the effects of introducing meningococcal B vaccination, as done for the type C vaccine.

Our reported CFR are fairly comparable with those of other European countries, where the CFRs range from 5.3% to 12.5%.25–29 Our data identify a higher CFR (14%), but this could relate partly to different data sources used to confirm mortality: laboratory base case data versus capture-recapture method including also HDRs, as in our study. In addition, the circulation in our geographical area of serotypes such as the ST-11 meningococci types (a hyper-virulent clone) leads to a high fatality rate, as isolated in the epidemic cluster of 2008 included in our results. An accurate serotyping achieved by involving microbiologists allows calculating the CFR for singular meningococcal serogroups.30–32 When MenB was considered alone in our analysis, the CFR was 16.4%, a figure similar to the one reported in the Italian paediatric population.21

It is impossible to say whether any patients with IMD died before reaching hospital. The time frame of these diseases is very short, but should be long enough to enable hospitalisation (deaths usually occur 24 hours after the first symptoms appear).33 A further development could involve making the mortality database part of the surveillance system.

Finally, from a quantitative point of view (number of cases of disease), the surveillance systems operating in Veneto and the HDRs identify cases of IMD approximately equally well, but the routine pooling of all available data sources affords a better epidemiological picture of IMD. The better quality of the data available from our surveillance systems is thanks mainly to the serological characterisation of the circulating meningococcal strains provided by microbiology laboratories, and molecular typing reduces the underestimation of cases resulting from cultures alone.34

The routine integration of different databases to build a single, web-based system in which all the actors (physicians, laboratorians, public health workers, emergency room workers and so on) can promptly input all the information on IMD at their disposal is crucial to the successful implementation and assessment of targeted prevention strategies and fundamental to public health decision-making.

bmjopen-2016-012478supp001.docx (18KB, docx)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the Local Health Authorities and the Microbiology Laboratories of the Veneto region for their essential role in the Invasive Bacterial Infections Surveillance Network.

Footnotes

Contributors: VB conceived the study. SC, PF and VB are responsible for the analysis and interpretation of the data. TB, RL and CB contributed to the interpretation of the results and drafted the manuscript. FR and MS provided data. All authors contributed to the critical revision of contents and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study received a research grant from the Veneto Regional Authority to support the surveillance activities.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Harrison LH, Pelton SI, Wilder-Smith A, et al. The Global Meningococcal Initiative: recommendations for reducing the global burden of meningococcal disease. Vaccine 2011;29:3363–71. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Greenwood BM. The epidemiology of acute bacterial meningitis in tropical Africa : Williams JD, Burnie J, Bacterial meningitis. London: Academic Press, 1987:61–91. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centers for Disease Control. Active bacterial corecore surveillance (ABCs) report emerging infections program network Neisseria meningitidis, 2009. Available on http://www.cdc.gov/abcs/reports-findings/survreports/mening09.pdf (accessed 18th Feb 2016).

- 4. Harrison LH, Trotter CL, Ramsay ME. Global epidemiology of meningococcal disease. Vaccine 2009;27(Suppl 2):B51–63. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kriz P, Wieffer H, Holl K, et al. Changing epidemiology of meningococcal disease in Europe from the mid-20th to the early 21st Century. Expert Rev Vaccines 2011;10:1477–86. 10.1586/erv.11.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bröker M, Emonet S, Fazio C, et al. Meningococcal serogroup Y disease in Europe: continuation of high importance in some European regions in 2013. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015;11:2281–6. 10.1080/21645515.2015.1051276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stefanelli P, Miglietta A, Pezzotti P, et al. Increased incidence of invasive meningococcal disease of serogroup C/clonal complex 11, Tuscany, Italy, 2015 to 2016. Euro Surveill 2016;21(12). 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2016.21.12.30176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Dati di sorveglianza delle malattie batteriche invasive aggiornati al 4 aprile 2016. http://www.iss.it/binary/mabi/cont/Report_MBI_20160404.pdf (accessed 12th Sep 2016).

- 9. Alfonsi V, D’Ancona F, Giambi C, et al. Current immunization policies for pneumococcal, meningococcal C, varicella and rotavirus vaccinations in Italy. Health Policy 2011;103:176–83. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Completeness and timeliness of reporting of meningococcal disease-Maine, 2001-2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2009;58:169–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ratnayake R, Allard R. Challenges to the surveillance of meningococcal disease in an era of declining incidence in Montréal, Québec. Can J Public Health 2013;104:335–9. 10.17269/cjph.104.3755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sáfadi MA, McIntosh ED. Epidemiology and prevention of meningococcal disease: a critical appraisal of vaccine policies. Expert Rev Vaccines 2011;10:1717–30. 10.1586/erv.11.159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Commission decision of 28 April 2008 amending decision 2002/253/EC laying down case definitions for reporting communicable diseases to the Community network under Decision No 2119/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council (notified under document number C(2008) 1589). Official Journal of the European Union, 2008/426/EC http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=uriserv:OJ.L_.2008.159.01.0046.01.ENG&toc=OJ:L:2008:159:TOC, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14. de Greeff SC, Spanjaard L, Dankert J, et al. Underreporting of meningococcal disease incidence in the Netherlands: results from a capture-recapture analysis based on three registration sources with correction for false positive diagnoses. Eur J Epidemiol 2006;21:315–21. 10.1007/s10654-006-0020-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martinelli D, Fortunato F, Cappelli MG, et al. Estimation of the impact of meningococcal serogroup C universal vaccination in Italy and suggestions for the multicomponent serogroup B vaccine introduction. J Immunol Res 2015;2015:1–9. 10.1155/2015/710656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wittes JT, Colton T, Sidel VW. Capture-recapture methods for assessing the completeness of case ascertainment when using multiple information sources. J Chronic Dis 1974;27:25–36. 10.1016/0021-9681(74)90005-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garante per la protezione dei dati personali 1 marzo 2012, n. 85: autorizzazione generale al trattamento di dati personali effettuato per scopi di ricerca scientifica. (Deliberazione n. 85).(12A03185). (GU n.72 del 26-3-2012).

- 18. Hook EB, Regal RR. Capture-recapture methods in epidemiology: methods and limitations. Epidemiol Rev 1995;17:243–64. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Centro Nazionale di Epidemiologia, Sorveglianza e Prevenzionedella Salute, Gruppo di Lavoro del CNESPS. Dati e evidenze disponibili per l’introduzione della vaccinazione anti-meningococco B nei nuovi nati e negli adolescenti. Istituto Superiore di Sanità, Giugno, 2014. Available on http://www.epicentro.iss.it/temi/vaccinazioni/pdf/IstruttoriaMENINGOCOCCOB.pdf (accessed 24 Feb 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Stefanelli P, Fazio C, Neri A, et al. National Surveillance System Collaborative Centers. Changing epidemiology of infant meningococcal disease after the introduction of meningococcal serogroup C vaccine in Italy, 2006-2014. Vaccine 2015;33:3678–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Azzari C, Canessa C, Lippi F, et al. Distribution of invasive meningococcal B disease in Italian pediatric population: implications for vaccination timing. Vaccine 2014;32:1187–91. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jafari HS, Perkins BA, Wenger JD. Control and prevention of meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report: Recommendations and Reports 1997;iv:10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Friedman SM, Sommersall LA, Gardam M, et al. Suboptimal reporting of notifiable diseases in canadian emergency departments: a survey of emergency physician knowledge, practices, and perceived barriers. Can Commun Dis Rep 2006;32:187–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Russo F, Pozza F, Napoletano G, et al. Experience of vaccination against invasive bacterial diseases in Veneto region (North East Italy). J Prev Med Hyg 2012;53:113–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Olivares R, Bouyer J, Hubert B. Risk factors for death in meningococcal disease. Pathol Biol 1993;41:164–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Connolly M, Noah N. Is group C meningococcal disease increasing in Europe? A report of surveillance of meningococcal infection in Europe 1993-6. European Meningitis Surveillance Group. Epidemiol Infect 1999;122:41–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shigematsu M, Davison KL, Charlett A, et al. National enhanced surveillance of meningococcal disease in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, January 1999-June 2001. Epidemiol Infect 2002;129:459–70. 10.1017/S0950268802007549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Steindl G, Liu YL, Schmid D, et al. Epidemiology of invasive meningococcal disease in Austria 2010. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2011;123(Suppl 1):10–14. 10.1007/s00508-011-0058-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ladhani SN, Flood JS, Ramsay ME, et al. Invasive meningococcal disease in England and Wales: implications for the introduction of new vaccines. Vaccine 2012;30:3710–6. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fazio C, Neri A, Tonino S, et al. Characterisation of Neisseria meningitidis C strains causing two clusters in the north of Italy in 2007 and 2008. Euro Surveill 2009;14:19179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ferro A, Baldo V, Cinquetti S, et al. Outbreak of serogroup C meningococcal disease in Veneto region, Italy. Euro Surveill 2008;13:8008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Neri A, Pezzotti P, Fazio C, et al. Epidemiological and molecular characterization of invasive meningococcal disease in Italy, 2008/09-2012/13. PLoS One 2015;10:e0139376 10.1371/journal.pone.0139376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Thompson MJ, Ninis N, Perera R, et al. Clinical recognition of meningococcal disease in children and adolescents. Lancet 2006;367:397–403. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67932-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Azzari C, Nieddu F, Moriondo M, et al. Underestimation of invasive meningococcal disease in Italy. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22:469–75. 10.3201/eid2203.150928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012478supp001.docx (18KB, docx)