Abstract

Background

Intensive care unit (ICU) personnel have an elevated prevalence of job-related burn-out and post-traumatic stress disorder, which can ultimately impact patient care. To strengthen healthcare workers’ skills to deal with stressful events, it is important to focus not only on minimising suffering but also on increasing happiness, as this entails many more benefits than simply feeling good. Thus, the purpose of this study was to explore the content of the ‘good things’ reported by healthcare workers participating in the ‘Three Good Things’ intervention.

Methods

In a tertiary care medical centre, a sample of 89 neonatal ICU (NICU) healthcare professionals registered for the online intervention. Of these, 32 individuals eventually participated fully in the 14-day online Three Good Things intervention survey. Daily emails reminded participants to reflect on and respond to the questions: “What are the three things that went well today?” and “What was your role in bringing them about?” To analyse their responses, we applied a thematic analysis, which was guided by our theoretical understanding of resilience.

Results

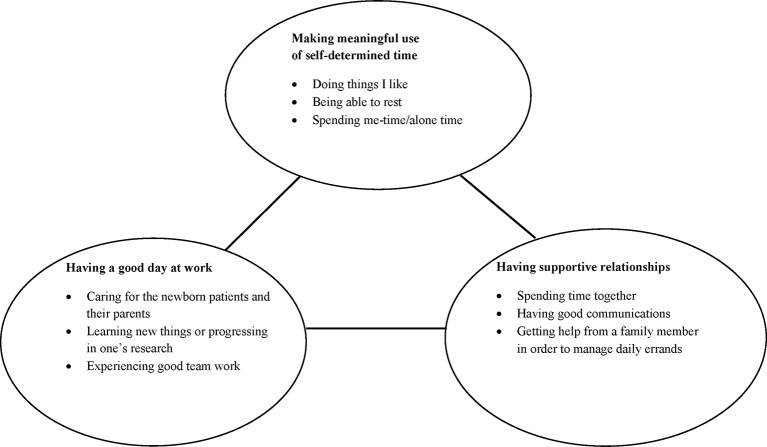

Involving more than 1300 statements, the Three Good Things responses of the 32 study participants, including registered nurses, physicians and neonatal nurse practitioners, led to the identification of three main themes: (1) having a good day at work; (2) having supportive relationships and (3) making meaningful use of self-determined time.

Conclusions

The findings show the personal and professional relevance of supportive relationships strengthened by clear communication and common activities that foster positive emotions. The Three Good Things exercise acknowledges the importance of self-care in healthcare workers and appears to promote well-being, which might ultimately strengthen resilience.

Keywords: Positive psychology, Well-being, Healthcare professionals, Self-care, Qualitative research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The ‘Three Good Things’ intervention has been replicated but has never before been used in healthcare to examine the themes that are generated regarding what is going well.

These themes offer opportunities for the large and growing number of healthcare leaders working to enhance the resilience of their workforce.

A relatively high participant dropout rate limits the generalisability of the study findings.

The results from this single work setting are not generalisable to other work settings in healthcare.

Introduction

Healthcare workers often face stressful situations including time constraints, high workload, multiple roles and emotionally challenging moments. The resulting strain can negatively impact workers’ resilience, resulting in burn-out and compromising their ability to provide the best possible care.1 In comparison to general medical/surgical nurses, intensive care unit (ICU) personnel have an increased prevalence of job-related burn-out and post-traumatic stress disorder.2–4 There is a need to enhance their resilience, that is, their ability to adapt, rebound and overcome adversity. Fortunately, resilience can be developed and improved and functions as a distinct defence against burn-out.5 6 Despite the benefits of strengthening it, however, relatively little qualitative research has been done to explore the best way to support the resilience of healthcare workers.

The American Psychological Association (APA) highlights that caring and supportive relationships within and outside the family strongly contribute to resilience.7 Interviewing nurses who had experienced post-traumatic stress, Mealer et al observed that highly resilient nurses identified spirituality, a supportive social network, optimism and role models as factors that helped them cope with stress in their work environments.3 In a review of the literature, Jackson et al reported on five factors that assist nurses in developing resilience: (1) building positive professional relationships through networks and mentoring; (2) maintaining positivity through laughter, optimism and positive emotions; (3) developing the emotional insight to understand one’s own risk and protective factors; (4) achieving work–life balance and using spirituality to give one’s life meaning and coherence; and (5) becoming more reflective.8 Additionally, being female and maintaining a work–life balance have consistently been associated with higher resilience across healthcare providers.9 The construct of resilience often includes topics such as mindfulness, purpose, relationships, self-care and self-awareness.5 The positive psychological movement has developed a number of mature interventions that facilitate and improve resilience in the general population and could be applied readily to healthcare workers.5

Positive psychological interventions

Conceived by Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi,10 the field of positive psychology focuses on valued subjective experience relating to the past (well-being, contentment and satisfaction), present (flow, a state of immersive, active engagement in one’s activities, which functions as a factor of happiness) and future (hope and optimism). Within these time contexts, positive psychology further focuses on minimising suffering and increasing happiness, because happiness brings many more benefits than simply feeling good.10 Happy people are healthier, more successful and more socially engaged.11 Happiness involves three attributes: (1) positive emotions and pleasure; (2) an engaged life; and (3) a meaningful life. Research has shown that the most satisfied people are those who orient their pursuits towards all three of these goals, with the greatest weight carried by engagement and meaning.12 Moreover, Seligman’s conceptual PERMA (positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning and achievement) model functions as a guide to help individuals find ways to flourish.13 In addition, positive psychology-based studies in organisations have clarified our understanding of how employees can flourish and achieve high potential at work. For example, da Camara et al have significantly linked meaning, engagement and pleasure in the workplace with positive organisational outcomes, for example, commitment and job satisfaction.14 Longitudinal intervention studies show that positive emotions play a role in the development of psychological resilience—a skill useful in effective long-term coping.15 Individuals who cultivate these positive factors can use them to cope with negative emotions. Yet, positive emotions are useful in helping distressed people deal with challenging situations and overcome negative emotions.16 Other findings from an internet-based ‘Three Good Things’ exercise highlight that participants who performed this exercise were happier and less depressed at the 1-month and 6-month follow-ups than at baseline.17

Overall, as shown in two meta-analyses,18 19 positive psychological interventions, including self-help, group and individual therapy (eg, Three Good Things, hope therapy, well-being therapy) have been effective in enhancing well-being as well as in reducing depressive symptoms. Although various interventions of this type—including online-based self-help techniques such as Three Good Things—focusing on symptom relief, well-being and happiness, have been applied both in healthy and in mentally distressed individuals, little specific information is available regarding the kinds of positive experiences that influence health professionals’ subjective well-being. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore the content of the good things reported by healthcare workers participating in the Three Good Things intervention.

Methods

Design and setting

A qualitative study using thematic analysis (TA) was applied to analyse written statements provided by study participants during the Three Good Things intervention. TA uses a systematic approach to identify patterns across a data set, enabling a rich and detailed analysis of participants’ perspectives.20 Led by a multidisciplinary team of neonatal experts in collaboration with specialised physicians, neonatal nurses and allied healthcare professionals, data were collected at an academic medical centre’s level 3 neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) in the USA.

Recruitment and sample

Study participants were recruited at the NICU during grand rounds (~150 eligible health professionals). A total of 89 health professionals (91% female) registered to participate. The sample included physicians, neonatal nurse practitioners, registered nurses, charge nurses and allied healthcare professions. Each participant completed an electronic informed consent form (study protocol ID: Pro00038083). The study was approved by the Duke Institutional Review Board.

Data collection

The data were collected in October 2012 using the ‘Qualtrics’ online survey tool. Once participants had registered, a daily email reminder was sent to them at 19:00 (EST) on each of the next 14 days. The reminder included a link to text boxes that prompted participants to answer What are the three things that went well today, and what was your role in bringing them about’. All written responses were stored in 14 Excel tables, that is, one table for each day’s three responses.

Data analysis

This study analysed the data of a sample of 32 participants who provided answers for at least 13 of the 14 days—more than 1300 statements. Responses were analysed using TA via a deductive approach, with data analysis and interpretation based on our theoretical understanding of resilience. The analysis incorporated a six-phase iterative process, with movement back and forth throughout the phases and a latent comparison with the original data20: (1) familiarisation with the data by reading and rereading the answers several times; (2) coding all answers; (3) identifying potential themes and subthemes and making comparisons between various participants’ data; (4) creating a thematic map and identifying themes for comparison with theoretical assumptions of resilience; (5) ongoing analysis to refine the specifics of each theme and to find the overall story narrative of the analysis and (6) generation of a report.

Results

Analysing the 32 participants’ Three Good Things responses led to the identification of three main themes: (1) having a good day at work; (2) having supportive relationships and (3) making meaningful use of self-determined time (figure 1). All quotations are intended to represent the larger group in this study and the phenomenon being explored.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the thematic findings of the Three Good Things exercise.

Having a good day at work

Participants regularly commented about a ‘good day at work’ or that their ‘day went smoothly’. One participant wrote, “Overall good day at work, no major problems with my patients” (032). Here a good day at work included the well-being of the caregiver’s patients. This was also illustrated in the statement, “My patient who had been wearing a brace to his foot for 3 hours on and 3 hours off does not need it anymore. It effectively corrected his foot position! Everyone who put the brace on made a difference!” (023). The importance of collaboration at work was frequently brought to the foreground. Effective teamwork was further enhanced by constructive communication, which was characterised through goal orientation and professional discussion with colleagues. This was demonstrated by responses such as: “Had a good and professional discussion with colleagues” (020), or “Great day at work, there were a couple of meetings that accomplished some previously set goals” (029).

A supportive work environment, adequate staffing, the ability to take breaks and manageable workloads made for a good day at work: “Unit ran smoothly, 5 in, 5 out” (016) was a common comment. Other participants commented about a peaceful, well managed, or quiet day at work: “Had a great, non-stressful assignment today and my shift went well” (025), or ‘Good calm day at work!” (003). The ability to leave work on time was often important for participants: “Got out of work on time; efficient work/ time management”(032). Other participants emphasised activities they could do with loved ones because they were able to leave on time: “I was able to get out of work on time so that I could spend time with my husband” (018). Ultimately, participants regarded getting out of work on time as an opportunity to engage in meaningful activities with loved ones.

Many participants mentioned that good teamwork and supportive coworkers were important: “Today I had the opportunity to work with an old co-worker and a new co-worker and we worked together very well. The day went smoothly and pleasantly because of my awesome podmates. They helped me with all my concerns and doubts and alleviated my fears” (025). Participants also regularly mentioned that it was good when they could help or support a coworker: “I assisted a co-worker through a very hectic day, so we both left on time!” (028). Having fun and laughing together was an important aspect of good teamwork. One participant wrote, “I had a few laughs with my podmate today that really lightened the mood on such a crazy day” (030). Another stated, “[I]laughed with my co-worker after having a long day at work” (007).

Having supportive relationships

“Cooked dinner and had the entire family home for a sit-down meal! Good times of laughing and sharing!” (028). This quotation captures several important aspects for participants: eating a meal together, spending time together, talking and laughing together and caring for the well-being of family members. One participant noted: “Had breakfast with my mom and dinner with my mom-in-law. Love family time on my day off!” (025). Relationships in various forms were seen as important and included family members, friends, coworkers and pets. One participant wrote: “Enjoyed family and neighbors at a block party” (020). Another wrote, “Enjoyed watching my dogs and cat play together/I just had to stop and watch them” (024). Some participants wrote about their love for family members or friends: “Felt loved because family and friends called to check on how I was feeling” (006).

As highlighted in previous themes, communication was an important aspect in fostering supportive relationships. This was illustrated by statements such as, “I had a productive family discussion with my children during dinner together” (002) or “Felt appreciated by my spouse because we had time to eat dinner together and talk” (006). Other statements included the aspect of talking and laughing together: “Had the opportunity to catch up with my husband. Good talk. Good laughs” (028). Similarly, participants stated the importance of their family members’ well-being: “My daughter is healthy” (007) or “My kids met their new Dr, got their vaccines, and weren't scared” (016). The health status of a family member was also often mentioned, as demonstrated by these statements: “Health of my mother improved a little” (026). Frequently, participants noted that a family member had returned safely from a trip: “I got all my kids home safe from their activities” (002), or “My honey made it to NY safely” (004).

Success at helping others in non-professional capacities was positively mentioned. One participant wrote, “My mom feels better with what I have researched what to eat for her renal failure” (012). Others supported their children for school tasks: “Found lots of books at the library that will help my son on his history project” (032). Alternatively, many participants were pleased when they were offered help with chores around the house: “On the way home stopped at the grocery store and bought items for a spaghetti supper. I was joined in the kitchen by my hubby who helped with the pasta and my son who washed dishes…then a family meal together. Doesn't take much to make me happy” ♥ (029). Frequently, when all errands were done the time was used to relax and was referred to as ‘me time’.

Making meaningful use of self-determined time

Many participants reported that they loved shopping, working in the garden, being physically active or reading a book. Participants wrote statements like: “Enjoyed the fabulous weather by working in the yard with my husband. The flowers look fabulous” (028), or “Completed my workout within the required time limit today” (030). Another person noted, “got to sit by the pool and read my book” (022). Individuals with dogs frequently went for walks: “I was off and I went for our daily early morning walk with my husband and our dogs… Felt very good after our walk” (019). Some participants mentioned that being active was important: “Awesome sunrise this morning during our walk/ de-stress by walking”(019). Further statements expressed the importance of sufficient relaxing sleep:“I was able to sleep in, all alone in a quiet house! Completely rested and rejuvenated!”(028). For several participants the ability to take ‘me time’ or ‘alone time’ was important. Statements such as “I took time for myself, enjoying a book and short nap” (028) and “Love having some alone time” (017) were frequent.

Discussion

Analysis of the NICU healthcare workers’ Three Good Things responses generated three key themes: (1) having a good day at work, (2) having supportive relationships and (3) making meaningful use of self-determined time. These themes suggest that achieving work satisfaction, relationship satisfaction and a sense of autonomy were prevalent components of self-reported positive emotions, offering a pillar on which to build additional resilience interventions for healthcare workers. References to tasks attempted to ease work-related difficulties dovetail with recommendations from the APA, which encourages individuals to play dynamic roles in achieving work satisfaction and solving work-related problems.7 Additionally, the importance of supportive relationships to psychological well-being has been well reported in the literature.3 5 21 This was captured when participants reported time spent with family members, friends, colleagues or pets as high points of their days. Being active together was a positive experience, because it demonstrated connectedness and produced emotional well-being, including joy (laugh together, enjoy activities together), pride (pride of an achievement of someone or her own), love and gratefulness.16 According to Fredrickson (2001), what makes positive emotions important to healthcare workers’ resilience building is that they come not in floods but steady trickles.3 8 9 In essence, this is what we feel the Three Good Things exercise does: it creates a structure that allows participants to reflect on frequent but relatively simple and small doses of positive emotion.

The APA encourages individuals to nurture meaningful connections, such as ‘good relationships with close family members, friends or others. Accepting help and support from those who are close and dear is an opportunity to establish such connections. Assisting others when they require help is also beneficial to the helper’.7 These were all dominant aspects captured in the Three Good Things responses. For example, ‘having supportive relationships’ captured the aspects of accepting and giving help. Caring for the well-being of others was essential in participants’ personal life as well as their work environment and included the importance of good communication. Comparable findings were identified by Jackson et al who reported that positive professional relationships built through networks and mentoring were important aspects for building resilience.8

The identified theme of ‘making meaningful use of self-determined time’ aligns with important aspects of autonomy, self-care and self-reflection (eg, paying attention to one’s own needs and feelings). On this point, the APA encourages individuals to ‘engage in activities that they enjoy and find relaxing. Their recommendations also highlight the importance of regular exercise.7 These points are supported by studies in which achieving life balance is consistently seen as an important aspect of resilience building in healthcare professionals.8 9

Implications for health professional leaders

This study highlights numerous important aspects of daily life that are important to health professionals and their leaders. One point that stands out, though, is that focusing on self-care provides a particular challenge for healthcare workers. Although self-care was often mentioned in statements by participants and was grouped under ‘making meaningful use of self-determined time’, where these activities were listed, they were often listed last. What this brings to the foreground is that, while self-care bolsters healthcare professionals’ ability to rebound from adversity and overcome difficult circumstances, many downplay its importance.22 23 In the end, if healthcare workers are not given the opportunity to attend to their own needs, while cultivating positive emotions, we might miss an important opportunity to build resilience in a vital group at risk for burn-out.

A variety of leadership instruments such as regular employee evaluations and career development meetings offer healthcare managers insights into what fosters positive emotions in their team members. As expressed in the Three Good Things exercise’, each of these instruments can address specific topics, for example, what contributes to a good day at work and what professional role does the respondent play in it or how does one create a work–life balance. Given that Three Good Things is a quick, low-cost and enjoyable activity for participants, it may serve as an effective intervention for healthcare leaders to promote in their work settings. Alternatively, supervisors might pose questions on positive experiences during team meetings, huddles or leadership walk-rounds to foster well-being and resilience in often challenging work and life situations. Simply starting a meeting with ‘What is one good thing so far this week?’ can bring these themes to the attention of leaders and coworkers alike. When reflecting on workers’ well-being and leadership contribution, contextual factors depict a complex interplay of individual and workplace characteristics. Among others, these include organisational attributes and work climate, job design and employee health.24 Clearly, this implies a comprehensive perspective at the organisational level, including interventions, for example, interventions to providing educational and career opportunities, flexible work arrangements and work scheduling, meaningful job content and enhanced participation both with colleagues and with supervisors.24 In essence, such interventions have to help match individuals’ skills and virtues with the demands of the workplace.14

Limitations

One of the limitations of the study was the relatively high dropout rate of participants during the 2-week data collection period. Only a third of participants provided answers for at least 13 of the exercise’s 14 days, while the others provided answers only for the first few days. Participants who provided incomplete information were excluded due to a lack of a full description of statements per day. Clearly, it was difficult to engage healthcare workers for the entire study duration; shift work likely contributed strongly to participants’ failure to complete the exercise. Further, the fact that the convenience sample was drawn entirely from a single unit may limit the generalisation of findings. Nevertheless, the in-depth information provided on positive experiences contributes to the understanding of healthcare professionals’ subjective well-being. What is brought to the foreground is what they think about and feel when asked what went well today.

Conclusion

This study highlights the importance of supportive relationships, open communication and common activities that foster positive emotions. Making meaningful use of personal time is a prevalent theme, although limited numbers of healthcare professionals appear to focus on maintaining a healthy work–life balance. This pilot study used NICU healthcare professionals as participants. Further healthcare studies should use this exercise to verify our findings. According to current research, positive emotions and self-care fulfil important resilience-building functions.18 25 Interventions are needed to increase healthcare professionals’ awareness of the importance of self-care for building resilience.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KR-L, OM and RS contributed to study conception, data analysis and interpretation. JBS contributed to study site management, data collection, analysis and interpretation. KR-L was responsible for manuscript drafting and editing. All authors contributed to manuscript drafting appraisal, revision and editing and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The study received no specific financial support from any public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Duke University Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional study data are available.

References

- 1. Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Bruyneel L, et al. . Nurses' reports of working conditions and hospital quality of care in 12 countries in Europe. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50:143–53. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Embriaco N, Papazian L, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. . Burnout syndrome among critical care healthcare workers. Curr Opin Crit Care 2007;13:482–8. 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3282efd28a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mealer M, Jones J, Moss M. A qualitative study of resilience and posttraumatic stress disorder in United States ICU nurses. Intensive Care Med 2012;38:1445–51. 10.1007/s00134-012-2600-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Poncet MC, Toullic P, Papazian L, et al. . Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:698–704. 10.1164/rccm.200606-806OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mc Allister M, Lowe JB. Resilienz und Resilienzförderung bei Pflegenden. Bern: Hofgreve, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Meyerson DA, Grant KE, Carter JS, et al. . Posttraumatic growth among children and adolescents: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev 2011;31:949–64. 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Psychological Association. The road to resilience. 2011.. www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience.aspx.

- 8. Jackson D, Firtko A, Edenborough M. Personal resilience as a strategy for surviving and thriving in the face of workplace adversity: a literature review. J Adv Nurs 2007;60:1–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04412.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McCann CM, Beddoe E, McCormick K, et al. . Resilience in the health professions: a review of recent literature. International Journal of Wellbeing 2013;3:60–81. 10.5502/ijw.v3i1.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seligman ME, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology. An introduction. Am Psychol 2000;55:5–14. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lyubomirsky S, King L, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: does happiness lead to success? Psychol Bull 2005;131:803–55. 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Seligman ME, Happiness A. NY: Free Press Taylor, SE (1989). Positive illusion. NY: Basic Books 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seligman ME. Flourish: a visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon and Schuster, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14. da Camara N, Hillenbrand C, Money K. Putting positive psychology to work in organisations. Journal of General Management 2009;34(3). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fredrickson B. The value of positive emotions. Am Sci 2003;91:330–5. 10.1511/2003.4.330 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol 2001;56:218–26. 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Seligman ME, Steen TA, Park N, et al. . Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. Am Psychol 2005;60:410–21. 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bolier L, Haverman M, Westerhof GJ, et al. . Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health 2013;13:119 10.1186/1471-2458-13-119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sin NL, Lyubomirsky S. Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: a practice-friendly meta-analysis. J Clin Psychol 2009;65:467–87. 10.1002/jclp.20593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Aronowitz T. The role of 'envisioning the future' in the development of resilience among at-risk youth. Public Health Nurs 2005;22:200–8. 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2005.220303.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cameron F, Brownie S. Enhancing resilience in registered aged care nurses. Australas J Ageing 2010;29:66–71. 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2009.00416.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Crane PJ, Ward SF. Self-Healing and Self-Care for Nurses. Aorn J 2016;104:386–400. 10.1016/j.aorn.2016.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wilson MG, Dejoy DM, Vandenberg RJ, et al. . Work characteristics and employee health and well-being: test of a model of healthy work organization. J Occup Organ Psychol 2004;77:565–88. 10.1348/0963179042596522 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tugade MM, Fredrickson BL. Regulation of positive emotions: emotion regulation strategies that promote resilience. J Happiness Stud 2007;8:311–33. 10.1007/s10902-006-9015-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.