Abstract

Objective

The modified early warning score (MEWS) is a ‘track and trigger’ score using routine physiological vital signs. The objective is to determine if the pretransfer MEWS can be used for predicting outcomes in trauma patients requiring interfacility transfer to higher levels of care.

Design, setting and participants

Retrospective study of consecutively transferred trauma patients into a level-II trauma centre from 2013 to 2014.

Interventions

None.

Outcome measures

Mortality, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, operative procedure, MEWS deterioration in-transit, air transport interfacility, secondary overtriage (low injury severity score (ISS) <10, LOS<1 day, discharged home) and severe injury (ISS ≥16). The association between the pretransfer MEWS and outcomes were analysed with Cochran-Armitage trend tests, receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves and univariate logistic regression.

Results

There were 587 transferred patients; outcomes were reported in 339 patients with complete data on all five vital signs used to calculate the MEWS. The MEWS ranged from 0 to 9 (median of 1). There was a significant linear relationship between MEWS and study outcomes, especially mortality, ICU admission, air medical transport and severe injury (p<0.001 for all). A threshold score ≥4 was identified by ROC analysis; 11.2% of patients had MEWS ≥4. Outcomes were significantly worse in patients with MEWS ≥4 versus <4: mortality (26.2% vs 3.0%, OR=11.59, p<0.001); ICU admission (73.7% vs 47.2%, OR=3.14, p=0.003); air transfer (42.1% vs 15.6%, OR=3.93, p<0.001) and severe injury (59.5% vs 27.2%, OR=3.9, p<0.001). The MEWS was not associated with surgery, in-transit MEWS deterioration or secondary overtriage.

Conclusion

Pretransfer MEWS ≥4 may be used by the receiving facility for predicting injury severity, mortality, air transport and ICU resource use. In the interfacility transport setting, the MEWS may be useful for identifying patients with less obvious need for transfer or requiring more expeditious transfer.

Keywords: Accident and emergency medicine, adult intensive and critical care, trauma management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The utility of the modified early warning score (MEWS), a ‘track and trigger’ score comprised of common physiological vital signs, has been previously described for risk deterioration in emergency department settings, but its utility has not been examined during interfacility transfer.

Emergency physicians and emergency medical service personnel did not prospectively use the MEWS during the study period so our findings need to be considered in combination with clinical judgement.

There was a considerable amount of missing vital signs at the transferring facility, resulting in nearly half of patients being removed from our outcomes analysis, although there were no differences in demographics, vital signs or outcomes in patients with missing versus complete vital signs.

The acuity of the patients was low, which may have prevented more robust analyses between MEWS and outcomes.

Introduction

Traumatic injury is the leading cause of death in persons under 45 years of age.1 Emergency medical service (EMS) personnel transported nearly 5 million patients with traumatic injury in 2008 alone.2 The prehospital care, triage and transport of patients with traumatic injury to a trauma centre are determined by protocols and guidelines published by the American College of Surgeons (ACS) Committee on Trauma (COT)3 and the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).2 However, not all injuries are immediately obvious, and patients are occasionally undertriaged to a lower level or non-trauma centre that requires interfacility EMS transport to a higher level trauma centre for care.

The mode of EMS transport interfacility is determined and requested by the transferring emergency physician. Communication between the transferring physician and the receiving trauma surgeon includes a review of physiological status, initial management and discussion on the optimal timing of transfer, such as stabilising patients prior to transfer. EMS agencies are staffed with providers having a range of training and experience dictating the scope of tasks they can perform, from administration of medications, use of medical devices, performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation, initiating ventilation and intubationand other monitoring techniques. While there are some criteria to help the transferring physician determine if the trauma patient should be transferred, for example patients with carotid or vertebral injuries, cardiac rupture and grade-IV or grade-V liver injuries,3 there are no solid guidelines on if, when and how a patient should be transferred. Field triage guidelines,2 3 although not explicitly intended for the interfacility transport or emergency department (ED) setting, could be used to aid in interfacility transfer of patients. These available guidelines may not be as useful as a composite score in the interfacility transport setting.

The modified early warning score (MEWS) is a ‘track and trigger’ score used for recognising patients who are at risk for deterioration and determines degree of illness of the patient.4 The initial validation of the MEWS was performed in 709 ED patients and identified MEWS ≥5 was associated with mortality and admission to the intensive care unit (ICU).5

Our objectives were to determine whether the MEWS can be used in the interfacility transport setting for patients with traumatic injury to detect patients potentially requiring higher levels of care. Specifically, we examined whether the pretransfer MEWS was associated with poor clinical outcomes, transport mode, injury severity and secondary overtriage.

Methods

Design, setting and participants

This was a retrospective cohort study that included all consecutively admitted trauma patients transferred into an ACS verified level-II trauma centre from another healthcare facility between January 1, 2013 and December 31, 2014 and followed through discharge of the index hospitalisation. The patient population was identified from the trauma registry called TraumaBase (CDM, Conifer, CO, USA), which is a registry used by the hospital and the State of Texas to track patients with traumatic injury for epidemiology and prevention studies as well as for quality assurance and quality improvement. Patients less than 18 years of age were excluded. We also excluded patients with no vital sign data (n=65, 10.0% of patients). This study received institutional review board approval with waiver of informed consent from The Medical Centre of Plano Institutional Review Board (study #163).

Modified Early Warning Score

The MEWS is derived from five common physiological vital signs of systolic blood pressure (SBP, mmHg), heart rate (HR, beats per minute), respiratory rate (RR, breaths per minute), temperature (T, °C) and alert, voice, pain, unresponsive score (AVPU score), figure 1. The Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is favoured to the AVPU in traumatic injury, and the AVPU was derived from the GCS as follows: A=14–15, V=9–13, p=4–8, U=3. This substitution is common although there is no standard method for estimating GCS from AVPU.6–10 The MEWS was calculated as the total of the five subcomponent scores (figure 1). Scores range from 0 to a maximum of 14.

Figure 1.

Modified early warning score (MEWS).

The pretransfer MEWS was calculated using vital signs from the transferring facility (obtained from the transfer facility record), before interfacility transport. The posttransfer MEWS was calculated from vital signs collected on arrival to the receiving facility.

Covariates and outcomes

Clinical outcomes included in-hospital mortality, ICU admission, surgical procedure, EMS transport mode (air medical vs ground transport), MEWS deterioration (an increase in MEWS during transit, calculated as the difference between pretransfer MEWS and posttransfer MEWS), secondary overtriage (injury severity score (ISS) <10, hospital LOS<1 day and discharged home) and severe injury (ISS ≥16).

The following demographic and clinical information was abstracted from the registry: vital sign information (vital sign location, timing and values before interfacility transport and on arrival at the receiving facility); demographics (age, gender, race); injury severity measures (abbreviated injury scale score, ISS, anatomic location of injury) and cause of injury. We also examined the occurrence of in-transit events, defined as a significant change in vital signs during transport (any normal to abnormal change in SBP, HR, RR, T and GCS) or procedures performed in transit (eg, fluid bolus, new or significant change in medication, sedation or paralytics, placement of chest tube or central line, needle decompression). Information on in-transit events were abstracted from detailed, scanned EMS run reports, which were only available in 149 charts.

Analysis

The association between pretransfer MEWS and outcomes were examined with Cochran-Armitage trend tests. Receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves were used to identify an optimal threshold score; we examined ROC curves for mortality and ICU admission, which were the outcomes used in the initial validation of the MEWS.5 This threshold score was examined in separate logistic regression models for each of our study outcomes to estimate the unadjusted odds of the threshold score for the outcome. The threshold score was also used to examine the proportion of patients who did not meet the physiological criteria outlined in the guidelines for triage to a trauma centre of GCS≤13, SBP ≤90 mm Hg and respirations <10 or >29 breaths/min signalling potential, impending deterioration.1 3

SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for all analyses, and p≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics and outcomes

There were 587 transferred patients in our study. The population had a median (IQR) age of 56 years (37–74), 60% were male, and the most common cause of injury was due to fall (57%), followed by a vehicular crash (28%). Nearly half of patients suffered a head injury (46%), although the acuity of neurologic deficit was low with a median GCS was 15 (15–15). Overall, 18% were transported interfacility by air medical services. The average distance travelled was 23 miles (range: 7–79 miles).

The rates of our study outcomes are shown in table 1. There was low mortality of less than 6% among our transferred trauma population, although half of patients were admitted to the ICU, 35% required surgery and 31% had a severe injury with ISS ≥16.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics by study population, defined by vital sign missingness

| % (n) | All five vital signs available (n=339) | Missing vital sign(s) (n=248) | p Value |

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years* | 54 (35–74) | 57 (40.5–78) | 0.05 |

| Male | 62.2 (211) | 56.9 (141) | 0.19 |

| White race | 73.5 (249) | 78.2 (194) | 0.18 |

| Fall cause of injury | 55.5 (188) | 58.1 (144) | 0.89 |

| Head injury | 44.0 (149) | 48.9 (121) | 0.25 |

| Neck or spine injury | 14.5 (49) | 16.5 (41) | 0.49 |

| Chest injury | 9.7 (33) | 9.7 (24) | 0.98 |

| Limb injury | 27.7 (94) | 25.4 (63) | 0.53 |

| MEWS subscore change from transferring to receiving facility | |||

| Deterioration in SBP | 3.83 (13) | 3.23 (8) | 0.76 |

| Deterioration in HR | 11.80 (40) | 14.11 (35) | 0.34 |

| Deterioration in RR | 9.44 (32) | 8.87 (22) | 1.0 |

| Deterioration in Temp | 0.29 (1) | 0 (0) | 1.0 |

| Deterioration in GCS | 6.49 (22) | 2.02 (5) | 0.07 |

| Outcomes | |||

| In-hospital mortality | 5.6 (19) | 8.1 (20) | 0.24 |

| ICU admission | 50.2 (170) | 51.2 (127) | 0.80 |

| Surgical procedure | 35.4 (120) | 29.4 (73) | 0.13 |

| Air transport, interfacility | 18.6 (63) | 18.2 (45) | 0.91 |

| MEWS deterioration | 21.9 (72) | 21.2 (52) | 0.99 |

| Secondary overtriage | 21.5 (73) | 22.2 (55) | 0.85 |

| Severe injury (ISS≥16) | 30.75 (103) | 32.39 (80) | 0.67 |

Data are presented as median (IQR).

GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; GSW, gunshot wound; HR, heart rate; ICU, intensive care unit; ISS, injury severity score; RR, respiratory rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure; Temp, temperaute. Secondary overtriage: ISS <10, hospital LOS<1 day and discharged home.

Additionally, 17.4% (26/149) experienced an in-transit event. The most common in-transit events were development of tachycardia or an abnormal RR (n=6 each), followed by development of hypotension (<90 mm Hg, n=4), administration of fluid bolus (n=4) and GCS decline of two or more points (n=3).

Modified early warning score

The majority of patients (90%) were not missing any vital signs posttransfer. However, 42% (n=248) were missing between one and four vital signs pretransfer (83% of those patients were missing only 1 vital sign). Thus, only 58% of patients (n=339) had complete data for all 5 vital signs.

We examined whether there were differences in demographics, clinical characteristics and outcomes in patients with complete vital sign data (n=339) vs missing vital sign(s) (n=248), table 1. There were no differences in any covariate or in any study outcome. We also examined whether there were differences in deterioration of the MEWS vital sign subscores between patients with complete vital sign data versus those with missing vital signs; no differences existed (table 1). Still, to be conservative we analysed the association between pretransfer MEWS and outcomes in those with complete vital sign data only (n=339), rather than using multiple imputation to calculate an imputed MEWS in patients with missing vital sign(s).

MEWS relationship to outcomes

The median (IQR) MEWS was 1 (1–2). As shown in table 2, the pretransfer MEWS showed a significant, linear relationship with study outcomes of mortality, ICU admission, air transport and severe injury. The pretransfer MEWS was borderline significant for predicting a surgical procedure.

Table 2.

Clinical and transit outcomes by pretransfer modified early warning score (MEWS)

| MEWS | MEWS % (n) | Mortality | ICU admission | Surgical procedure | Air transport | MEWS deterioration | Secondary overtriage | Severe injury (ISS≥16) |

| 0 or 1 | 69.6 (236) | 2.1% | 45.8% | 31.8% | 14.0% | 19.3% | 22.5% | 24.0% |

| 2 | 13.6 (46) | 4.4% | 52.2% | 45.7% | 23.9% | 34.9% | 23.9% | 32.6% |

| 3 | 5.6 (19) | 10.5% | 52.6% | 36.8% | 15.8% | 5.9% | 10.5% | 52.6% |

| 4 | 5.6 (19) | 15.8% | 63.2% | 42.1% | 15.6% | 22.2% | 26.3% | 61.1% |

| 5 | 3.5 (12) | 16.7% | 75.0% | 41.7% | 66.7% | 8.3% | 16.7% | 41.7% |

| ≥6 | 2.1 (7) | 71.4% | 100% | 57.1% | 71.4% | 20.0% | 0% | 100% |

| p Value | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.07 | <0.001 | 0.65 | 0.27 | <0.001 |

ICU, intensuve care unit; ISS, injury severity score.

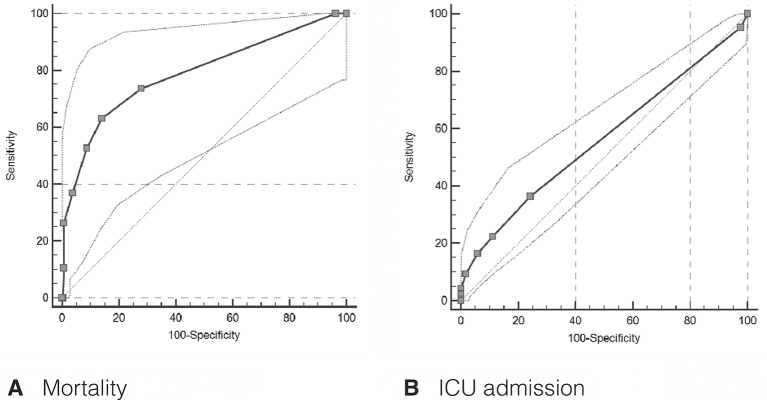

Threshold scores were determined with ROC curves (figure 2). The ROC curve for mortality was clinically and statistically significant (AUROC: 0.79 (95% CI: 0.74 to 0.83, p<0.001), identifying a threshold MEWS ≥4 for predicting mortality with a high specificity of 91.3 (91% of survivors were correctly identified by a pretransfer MEWS <4) and good sensitivity of 52.6 (53% of patients who expired were correctly identified by a MEWS ≥4), figure 2a. The ROC curve for ICU admission was weaker but still statistically significant (AUROC: 0.56 (95% CI: 0.51 to 0.62, p=0.02), demonstrating specificity of 94.1 and sensitivity of 16.5 with a threshold MEWS ≥4 on ROC analysis, figure 2b.

Figure 2.

(A) Receiver operator characteristic curves for mortality. (B) Intensive care unit (ICU) admission.

When the threshold score ≥4 was modelled for our outcomes, the pretransfer MEWS continued to show a significant association with study outcomes of mortality, ICU admission, air transport and severe injury (table 3).

Table 3.

Association between clinical outcomes with pretransfer modified early warning score (MEWS) threshold of ≥4

| Outcomes, % (n) | MEWS<4, n=301 | MEWS≥4, n=38 | OR* (95% CI) | p Value |

| In-hospital mortality | 3.0 (9) | 26.2 (10) | 11.6 (4.4 to 30.9) | <0.001 |

| ICU admission | 47.2 (142) | 73.7 (28) | 3.1 (1.5 to 6.7) | 0.003 |

| Surgical procedure | 34.2 (103) | 44.7 (17) | 1.6 (0.8 to 3.1) | 0.20 |

| Air transport, interfacility | 15.6 (47) | 42.1 (16) | 3.9 (1.9 to 8.0) | <0.001 |

| MEWS deterioration | 21.0 (57) | 17.1 (6) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.7) | 0.43 |

| Secondary overtriage | 21.9 (66) | 18.4 (7) | 0.8 (0.3 to 1.9) | 0.62 |

| Severe injury (ISS≥16) | 27.2 (81) | 59.5 (22) | 3.9 (1.9 to 8.0) | <0.001 |

*Odds ratio for MEWS ≥4 versus MEWS <4, analysed with univariate logistic regression.

ICU, intensive care unit; ISS, injury severity score. Secondary overtriage: ISS <10, hospital LOS<1 day and discharged home.

In patients with MEWS ≥4, 45% (17/38) did not have abnormal physiological vital signs signalling triage to a trauma centre by the ACS COT and CDC decision guidelines; further, 63% (12/19) of patients with a MEWS=4 would not have met the physiological criteria outlined in the guidelines. Outcomes in these 12 patients include one death, seven admissions to the ICU, five patients requiring surgery, but only three patients transferred by air. Ninety-five per cent (286/301) of patients with MEWS <4 did not have abnormal vital signs per the guidelines.

Discussion

Our study examined patients with traumatic injury requiring interfacility transfer, demonstrating that a MEWS ≥4 calculated prior to interfacility transport is associated with mortality, ICU admission, air medical transport and severe injury. In the interfacility transport setting, the MEWS may act as a more holistic measure that may lessen the chance of underestimating a poor clinical outcome and delaying or not transferring a patient appropriately. While it may seem obvious that out-of-range vital signs would increase the odds of an unfavourable outcome, only 21 of 38 patients with MEWS ≥4 would have met abnormal physiological criteria by the ACS COT and CDC decision guidelines.1 3 In this setting, the MEWS may be useful for identifying patients with less obvious need for transfer.

The main limitation of the study is that emergency physicians and EMS personnel did not prospectively use the MEWS during the study period so our findings need to be considered in combination with clinical judgement. Fullerton et al observed that the MEWS in combination with clinical judgement increases the utility of the MEWS in a prehospital setting.4 At least one study reported that implementing the MEWS in a trauma setting did not result in a statistically significant reduction in mortality (p=0.09).11 A prospective study that factors in clinical judgement will need to validate this threshold of ≥4 to determine if it leads to more appropriate transfer and improved outcomes.

Additional limitations are as follows: There was a considerable amount of missing vital sign data at the transferring facility, resulting in 47% of patients being removed from our outcomes analysis. While there were no differences in the characteristics or outcomes of patients with complete data and patients with incomplete data, there may be some residual bias in excluding patients with one or more missing vital signs. This limitation also suggests a need for more efficient, routine collection of pretransport vital signs and EMS reports to receiving facilities. Next, the acuity of the patients was low, which may have prevented more robust analyses between MEWS and outcomes. The median pretransfer MEWS was only 1. This might not be a limitation as much as it suggests that guidelines for the prehospital triage and transport of patients attempt to minimise undertriage of trauma patients at the expense of overtriage. Further study is needed to examine the MEWS for interhospital transport to level-I trauma centres. Patients transferred into level-I trauma centres theoretically have higher acuity injuries and more severe MEWS prehospital, which may help with the robustness of these analyses. Finally, the AVPU component of the MEWS score was estimated from the GCS. There are no standard criteria for estimating GCS from AVPU6–10; using a different cut-off might result in different MEWS scores.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: MG and JJ conceived the study. KS and JJ designed the study. KS performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. JJ was involved in data selection and data collection. MG, MC and DBO contributed substantially to its revision. DBO takes responsibility for the manuscript as a whole.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not obtained

Ethics approval: The Medical Center of Plano Institutional Review Board (study #163)

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available from corresponding author DBO.

References

- 1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National center for injury prevention and control. Injury Prevention and Control- leading causes of death 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for field triage of trauma patients. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2011;13:2012. [Google Scholar]

- 3. American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma. Resources for the optimal care of the injured patient. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fullerton JN, Price CL, Silvey NE, et al. . Is the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) superior to clinician judgement in detecting critical illness in the pre-hospital environment? Resuscitation 2012;83:557–62. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Subbe CP, Kruger M, Rutherford P, et al. . Validation of a modified early warning score in medical admissions. QJM 2001;94:521–6. 10.1093/qjmed/94.10.521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kelly CA, Upex A, Bateman DN. Comparison of consciousness level assessment in the poisoned patient using the alert/verbal/painful/unresponsive scale and the Glasgow Coma scale. Ann Emerg Med 2004;44:108–13. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McNarry AF, Goldhill DR. Simple bedside assessment of level of consciousness: comparison of two simple assessment scales with the Glasgow Coma scale. Anaesthesia 2004;59:34–7. 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03526.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Raman S, Sreenivas V, Puliyel JM, et al. . Comparison of alert verbal painful unresponsiveness scale and the Glasgow Coma score. Indian Pediatr 2011;48:331–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wasserman EB, Shah MN, Jones CM, et al. . Identification of a neurologic scale that optimizes EMS detection of older adult traumatic brain injury patients who require transport to a trauma center. Prehosp Emerg Care 2015;19:202–12. 10.3109/10903127.2014.959225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zadravecz FJ, Tien L, Robertson-Dick BJ, et al. . Comparison of mental-status scales for predicting mortality on the general wards. J Hosp Med 2015;10:658–63. 10.1002/jhm.2415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patel MS, Jones MA, Jiggins M, et al. . Does the use of a "track and trigger" warning system reduce mortality in trauma patients? Injury 2011;42:1455–9. 10.1016/j.injury.2011.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leung SC, Leung LP, Fan KL, et al. . Can prehospital Modified Early Warning score identify non-trauma patients requiring life-saving intervention in the emergency department? Emerg Med Australas 2016;28:84–9. 10.1111/1742-6723.12501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gu M, Fu Y, Li C, et al. . The value of modified early warning score in predicting early mortality of critically ill patients admitted to emergency department. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 2015;27:687–90. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.2095-4352.2015.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reini K, Fredrikson M, Oscarsson A. The prognostic value of the Modified Early Warning score in critically ill patients: a prospective, observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2012;29:152–7. 10.1097/EJA.0b013e32835032d8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Patel A, Hassan S, Ullah A, et al. . Early triaging using the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) and dedicated emergency teams leads to improved clinical outcomes in acute emergencies. Clin Med 2015;15(Suppl 3):s3 10.7861/clinmedicine.15-3-s3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kruisselbrink R, Kwizera A, Crowther M, et al. . Modified early warning score (MEWS) Identifies critical illness among Ward Patients in a Resource Restricted Setting in Kampala, Uganda: a prospective Observational Study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0151408 10.1371/journal.pone.0151408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. The EAST Practice Management Guidelines Work Group. Practice Management guidelines for the Appropriate Triage of the Victim of Trauma: eastern Association for the surgery of Trauma, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.