Abstract

Background

Platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) have been reported to reflect the inflammatory response and disease activity in a variety of autoimmune diseases.

Objectives

This study aimed to evaluate the value of PLR and NLR as markers to monitor disease activity in Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK).

Methods

A retrospective case–control study involving 88 patients with TAK and 78 healthy controls was performed. We compared the PLR and NLR between patients and healthy controls, and also analysed the correlations between PLR or NLR and indices of TAK disease activity.

Results

Increased PLR and NLR were observed in patients with TAK. PLR was positively correlated with hs-C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) (r=0.239, p=0.010) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (r=0.270, p=0.010). NLR also exhibited a positive relationship with Kerr’s score (r=0.284, p=0.002), hs-CRP (r=0.313, p=0.006) and ESR (r=0.249, p=0.019). A PLR level of 183.39 was shown to be the predictive cut-off value for TAK (sensitivity 37.8%, specificity 93.0%, area under the curve (AUC)=0.691). A NLR level of 2.417 was found to be the predictive cut-off value for TAK (sensitivity 75.6%, specificity 55.8%, AUC=0.697).

Conclusions

PLR and NLR could be useful markers to reflect inflammation and disease activity in patients with TAK.

Keywords: Takayasu’s arteritis, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratios

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the first to assess the PLR and NLR as possible markers of inflammation and disease activity in patients with TAK.

It provides accurate cut-off values for PLR and NLR to evaluate disease activity of TAK.

This study provides a simple and convenient method for the clinical evaluation of TAK disease activity.

This is a retrospective cross–sectional study; a prospective cohort study should be carried out in the future.

Introduction

Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK) is a systemic autoimmune large vessel vasculitis, mainly involving the aorta and its branches. TAK causes aortic injury such as stenosis, occlusion, haemangioma or dissection and other serious complications which result in tissue and organ ischaemia, dysfunction and even vascular rupture leading to sudden death in severe cases.1 The pathology of TAK is characterised by inflammatory cell infiltration along with granulomatous inflammation as well as by excessive proinflammatory cytokine production.2 Inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are commonly used to monitor disease progression. Although CRP and ESR are often useful to follow patients with TAK, some patients suffer from worsening of vasculitis without increasing CRP or ESR. These systemic inflammatory markers do not always show a positive correlation with inflammatory activity in the vessel wall.3

Recent studies have shown that an abnormal neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) is also associated with autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis,4 ulcerative colitis,5 rheumatoid arthritis (RA),6 systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS)7 and Behçet’s disease.8 Platelets also play an active role in inflammation and have regulatory roles in the immune system, so the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) has also been suggested in recent years as a potential marker to determine inflammation. Similar to NLR, PLR is also used as an index for differential diagnosis or prognostic prediction of diverse diseases such as cancer,9 metabolic syndrome10 and inflammatory diseases, especially for evaluating cardiovascular risk and events.11 However, research on the association of PLR and NLR with TAK is limited. Therefore, in this retrospective study we analysed the medical records of 88 patients with TAK and 78 healthy individuals to evaluate the PLR or NLR in patients with TAK and compared it with controls.

The aim of the study was to define the possible association of PLR and NLR with the inflammatory response and disease activity in TAK. The relationship of PLR or NLR with TAK disease activity was also evaluated.

Methods

Patients

A total of 88 patients with TAK were enrolled in this retrospective study according to the criteria for classification of TAK developed by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) in 1990. All the patients had glucocorticoid withdrawal for at least 6 months or were newly diagnosed without treatment, and patients with drug-related reduction in white blood cells were excluded. Patients who had chronic or current infections, tumours, haematologic diseases, other autoimmune diseases, lymphoproliferative disorders, hepatosplenic diseases or a history of allergic diseases were also excluded. Disease activity was assessed in patients with TAK using a modified version of Kerr’s criteria. Kerr’s criteria are used to define ‘active disease’ if two of the following criteria are positive: (1) systemic features with no other cause; (2) elevated ESR; (3) indications of vascular ischaemia or inflammation (eg, claudication, diminished or absent pulses, bruit, vascular pain, asymmetric blood pressure); or (4) typical angiographic features (including any imaging method in addition to conventional angiography). All the patients were recruited from the Department of Rheumatology and Immunology, Beijing Anzhen Hospital during the period from January 2013 to December 2015. Seventy-eight age- and sex-matched healthy donors were recruited from the healthcare centre of Anzhen Hospital as controls. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Anzhen Hospital.

Blood sample collection

For each subject, 4 mL of venous blood was drawn in the morning after 12 hours of fasting. The blood was then placed in a tube without anticoagulation and the serum was collected after the blood was coagulated and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. The total and differential leucocyte counts were determined using a Beckman Coulter LH 780 (Beckman Coulter Ireland, Mervue, Galway, Ireland). A Hitachi 7600–120 automatic biochemical analyser was used to test the serum parameters.

Statistical analysis

Values are expressed as mean±SE. Differences between measured parameters in patients and controls were assessed by the unpaired t-test. If the data were not normally distributed, the Mann–Whitney test was applied; the assessment of qualitative parameters was performed by the χ2test. Pearson’s approach was used to quantitate the correlation between variables. A receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed to determine the predictive value of PLR and NLR in the patient group. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical studies were carried out with the SPSS program V.16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Results

Basic characteristics of the study sample

Clinical characteristics and laboratory findings of the 88 patients with TAK and 78 healthy controls are given in table 1. Patients with TAK had a median age of 39.35 years (range 17–63), with a gender distribution of 78 women (88.63%) and 10 men (11.36%). In the control group the median age was 36.46 years (range 18–57) with a gender distribution of 68 women (87.18%) and 10 men (12.82%). There was no difference in age or gender between the TAK and control groups. The total white blood cell (WBC) and neutrophil counts were significantly higher in the patient group (p=0.000 and p=0.000, respectively). PLR and NLR were markedly elevated in patients with TAK compared with controls (p=0.023 and p=0.001, respectively). ESR and serum hs-CRP levels were higher in the patient group than in controls (p=0.000 and p=0.000, respectively). No differences in other blood parameters such as lymphocyte (LY) count, platelet count, serum levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine (Cr) were observed between the groups (table 1).

Table 1.

Laboratory parameters of patients with TAK and healthy controls

| Parameters | Controls (n=78) | TAK patients (n=88) | p Value |

| Age (years) | 36.46±7.23 | 39.35±15.03 | 0.235 |

| Gender (female/male) | 68/10 | 78/10 | 0.774 |

| WBC (109/L) | 5.53±1.60 | 7.43±2.88 | 0.000 |

| LY (109/L) | 1.72±0.46 | 1.81±0.73 | 0.342 |

| NE (109/L) | 3.37±1.29 | 4.97±2.44 | 0.000 |

| PLT (109/L) | 247.21±45.49 | 241.82±79.69 | 0.387 |

| MPV (fL) | 10.21±0.98 | 10.37±0.97 | 0.269 |

| PDW % | 12.43±1.73 | 11.98±1.95 | 0.052 |

| ALT (U/L) | 15.40±8.94 | 17.00±12.48 | 0.152 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 5.31±2.01 | 5.52±3.29 | 0.177 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 63.87±10.47 | 75.57±14.37 | 0.422 |

| ESR (mm/hour) | 4.39 (2.00–12.00) | 19.62 (1.00–92.00) | 0.000 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 0.63 (0.08–2.30) | 9.50 (0.08–38.62) | 0.000 |

| NLR | 2.01±0.89 | 3.86±3.28 | 0.001 |

| PLR | 149.58±39.65 | 167.44±76.58 | 0.023 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein;LY, lymphocyte; MPV, mean platelet volume; NE, neutrophil; NRL, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PDW, platelet distribution width; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLT, platelet; n, number of patients; TAK, Takayasu’s arteritis; WBC, white blood cell.

PLR and NLR were increased in TAK patients with disease activity

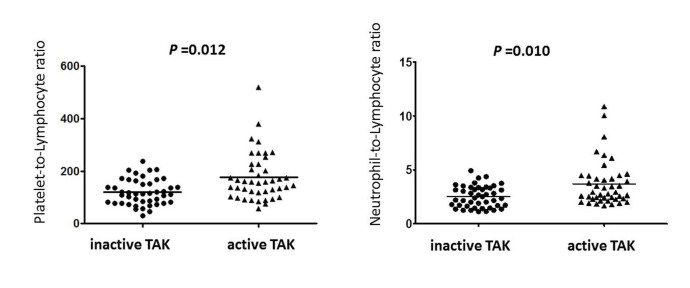

The total WBC count, neutrophil count and platelet count were all increased in the active TAK group (p=0.001, p=0.001 and p=0.004, respectively). Serum immunoglobulin (Ig)A, IgG and complement 3 (C3) were significantly higher in the active TAK group than in the inactive patients (p=0.007, p=0.011 and p=0.000, respectively). ESR and serum hs-CRP levels were higher in the active patient group than in the inactive group (p=0.000 and p=0.000, respectively; table 2). As shown in figure 1, both PLR and NLR were significantly elevated in patients with active TAK compared with the inactive group (p=0.012 and p=0.010, respectively; figure 1).

Table 2.

Comparison of parameters in patients with active and inactive TAK

| Parameters | Inactive TAK (n=45) | Active TAK (n=43) | p Value |

| Age (years) | 39.54±14.75 | 37.90±15.68 | 0.227 |

| Gender (female/male) | 41/4 | 37/6 | 0.454 |

| Disease duration (months) | 15.59±6.86 | 13.94±7.43 | 0.853 |

| WBC (109/L) | 6.61±2.04 | 8.74±3.65 | 0.001 |

| LY (109/L) | 1.77±0.62 | 1.87±0.81 | 0.526 |

| NE (109/L) | 4.33±1.81 | 5.86±2.34 | 0.001 |

| PLT (109/L) | 224.16±64.14 | 266.34±91.68 | 0.004 |

| ALT (U/L) | 19.49±16.06 | 17.62±9.46 | 0.622 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 5.69±3.96 | 5.26±2.21 | 0.498 |

| Cr (μmol/L) | 71.10±21.12 | 81.60±14.75 | 0.563 |

| IgA (g/L) | 1.82±0.95 | 2.57±1.30 | 0.007 |

| IgG (g/L) | 9.50±2.27 | 11.58±4.57 | 0.011 |

| IgM (g/L) | 1.33±0.76 | 1.38±0.85 | 0.812 |

| C3 (g/L) | 0.97±0.15 | 1.21±0.20 | 0.000 |

| C4 (g/L) | 0.59±0.29 | 0.71±0.32 | 0.079 |

| ESR (mm/hour) | 8.39 (1.00–19.00) | 33.81 (4.00–92.00) | 0.000 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 1.85 (0.08–32.83) | 20.04 (0.49–38.62) | 0.000 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine; C3, complement 3; C4, complement 4; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; hs-CRP, high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IgA, immunoglobulin A; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; LY, lymphocyte; NE, neutrophil; n, number of patients; PLT, platelet; TAK, Takayasu’s arteritis; WBC, white blood cell.

Figure 1.

Comparison of platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio between patients with inactive and active Takayasu’s arteritis (TAK).

PLR and NLR had positive correlations with disease activity in patients with TAK

As shown in table 3, PLR was positively correlated with hs-CRP (r=0.239, p=0.010) and ESR (r=0.270, p=0.010). NLR also exhibited a positive relationship with Kerr’s score (r=0.284, p=0.002), hs-CRP (r=0.313, p=0.006) and ESR (r=0.249, p=0.019) (table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation of laboratory findings with disease activity in patients with TAK

| Kerr’s score | hs-CRP | ESR | ||||

| r | p Value | r | p Value | r | p Value | |

| WBC | 0.336 | 0.000 | 0.458 | 0.000 | 0.388 | 0.000 |

| LY | 0.054 | 0.602 | 0.119 | 0.205 | 0.276 | 0.023 |

| NE | 0.311 | 0.001 | 0.466 | 0.000 | 0.327 | 0.356 |

| PLT | 0.353 | 0.000 | 0.345 | 0.000 | 0.490 | 0.000 |

| PLR | 0.185 | 0.052 | 0.239 | 0.010 | 0.270 | 0.010 |

| NLR | 0.284 | 0.002 | 0.313 | 0.006 | 0.249 | 0.019 |

LY, lymphocyte; NE, neutrophil; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLR, platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio; PLT, platelet; TAK, Takayasu’s arteritis; WBC, white blood cell.

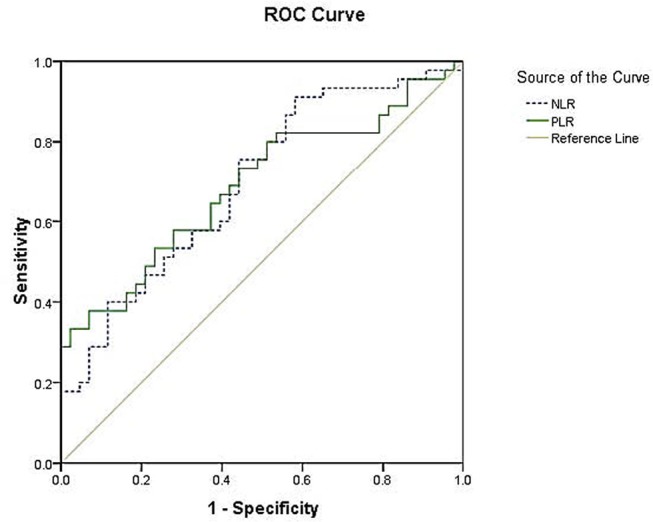

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves of PLR and NLR for TAK disease activity

We performed a ROC analysis to determine whether the best cut-off values for PLR and NLR predict TAK disease activity (Kerr’s score). For PLR, the area under the curve was 0.691 (95% CI 0.580 to 0.802, p=0.002) and the best cut-off value was 183.390, with sensitivity and specificity of 37.8% and 93.0%, respectively. For NLR, the area under the curve was 0.697 (95% CI 0.588 to 0.806, p=0.001) and the best cut-off value was 2.417, with sensitivity and specificity of 75.6% and 55.8%, respectively (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (Kerr criteria as the standard). For PLR, the area under the curve was 0.691, with 37.8% sensitivity and 93.0% specificity. For NLR, the area under the curve was 0.697, with sensitivity and specificity of 75.6% and 55.8%, respectively.

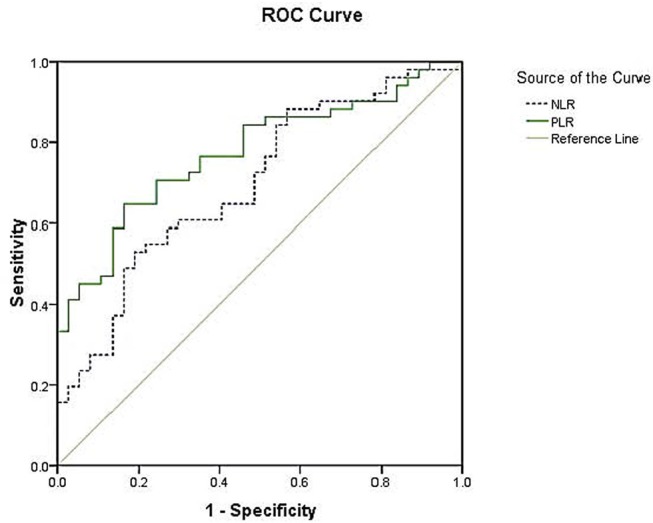

Using hs-CRP as standard, for PLR the area under the curve was 0.775 (95% CI 0.687 to 0.871, p=0.000) and the best cut-off value was 152.872, with sensitivity and specificity of 64.7% and 83.9%. For NLR, the area under the curve was 0.698 (95% CI 0.588 to 0.808, p=0.002) and the best cut-off value was 3.321, with sensitivity and specificity of 52.9% and 81.1% (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (C-reactive protein as the standard). For PLR, the area under the curve was 0.775, with 64.7% sensitivity and 83.8% specificity. For NLR, the area under the curve was 0.698, with sensitivity and specificity of 52.9% and 81.1%, respectively.

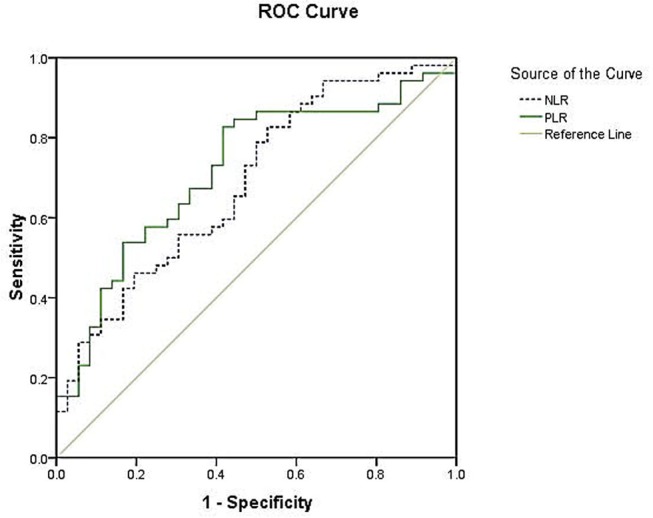

Using ESR as standard, for PLR the area under the curve was 0.718 (95% CI 0.609 to 0.827, p=0.001) and the best cut-off value was 158.514, with sensitivity and specificity of 53.8% and 83.3%, respectively. For NLR, the area under the curve was 0.688 (95% CI 0.576 to 0.800, p=0.003) and the best cut-off value was 2.072, with sensitivity and specificity of 82.7% and 47.2%, respectively (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (erythrocyte sedimentation rate as the standard). For PLR, the area under the curve was 0.718, with 53.8% sensitivity and 83.3% specificity. For NLR, the area under the curve was 0.688, with sensitivity and specificity of 82.7% and 47.2%, respectively.

Discussion

This study analysed the correlations of PLR and NLR with disease activity in patients with TAK. The findings first showed that both PLR and NLR were increased in TAK, especially in patients with disease activity. There were positive correlations in patients with TAK between PLR and disease activity and between NLR and disease activity. Furthermore, our results suggest that PLR and NLR may be potential indicators of assessment of the disease activity in TAK.

Platelets play an active role in inflammation. In many studies of inflammatory arthritis, evidence has been found for an increase in platelet activation.11 12 Platelet inhibition was found to counterbalance the rises in interleukin 6 (IL-6) and CRP in patients with acute cardiovascular diseases. Platelets extensively interact with leucocytes in vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis and are regarded as central players in the pathophysiology of vascular inflammation. Increased mass of circulating platelets is probably a consequence of chronic inflammation. Activated platelets not only produce growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor-β, but also release chemokines, which have important effects in vascular inflammation leading to thrombosis.13 Similar to other inflammatory diseases, even in patients with inactive TAK the risk of atherosclerosis is also increased.14 It has been suggested that the scores of delayed contrast-enhanced MRI are moderately correlated with CRP, platelet count and fibrinogen levels (p<0.05).15 There are some basic studies about the use of antiplatelet agents in TAK.16 17 Antiplatelet treatment may also lower the frequency of ischaemic events in TAK.18 In the limb affected by arterial stenosis, more platelet aggregation and higher levels of thromboxane were reported in patients with TAK, and these findings were shown to improve after treatment with aspirin 80 mg/day.14 It is believed that endothelial injury and dysfunction caused by increased platelet activity and vascular inflammation are important factors for thrombosis development in TAK. A recent retrospective observational study suggested that antiplatelet therapy was associated with a lower frequency of ischaemic events in patients with TAK.19 Prednisone at a dosage of 1 mg/kg twice a day decreased the platelet count within 45 days of its initiation. TAK should be considered in the differential diagnosis of unexplained thrombocytosis, particularly in young women.20 In the current study there was no difference in platelet counts between TAK patients and controls, while the platelet counts of active patients were significantly higher than those of inactive patients, and correlated with disease activity indices such as hs-CRP and ESR. ROC analysis has suggested that PLR predicts TAK disease activity. Our results indicate that the platelet is activated in TAK, in parallel with disease activity.

Neutrophils, also essential mediators of host defence, can produce many inflammatory mediators and cytokines and bridge the innate and adaptive immune responses in autoimmune diseases.21 Research evidence has demonstrated that neutrophils persist beyond acute inflammation to initiate and perpetuate chronic inflammation. Recent studies have indicated that changes in neutrophils are involved in the development of a variety of autoimmune diseases. There was a higher NLR in patients with psoriasis vulgaris than in the control group,4 and the abnormal NLR level was associated with RA,6 SLE, pSS10 and Behçet’s disease.8 Another study investigated the neutrophil–platelet interaction in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis and suggested that platelet–neutrophil aggregates correlate positively with the disease activity score.22 Proinflammatory cytokines IL-17, IL-8, interferon γ and tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α) also play prominent roles in the recruitment, activation and survival of neutrophils at inflammatory sites,23 and expression of these cytokines was significantly increased in TAK.24 In RA, anti-TNF-α therapies reduce IL-33 receptor expression on neutrophils and subsequently decrease neutrophil migration, and impaired chemotaxis of neutrophils may lead to a decrease in inflammation and disease severity in RA.25 Our data showed that neutrophils were increased in patients with TAK and were positively correlated with disease activity. This is similar to previous results in other autoimmune diseases. Similarly, our study found that both total WBC and neutrophil counts were significantly higher in patients with TAK than in controls, and NLR was significantly higher in patients with active disease. In order to clarify the correlations between NLR and TAK disease activity, we evaluated the level of the NLR and Kerr’s score, hs-CRP and ESR in patients with TAK and found that NLR is positively correlated with TAK disease activity. All these findings suggest that PLR and NLR could be used to reflect the inflammatory response and disease activity in TAK.

This was a retrospective study of a sample of patients undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, which may influence the peripheral cell counts. A prospective cohort study with larger numbers of TAK cases is needed to clarify the mechanism of PLR and NLR in TAK disease activity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study is the first to assess PLR and NLR in patients with TAK and evaluates their relationship with disease activity. We found a higher level of PLR and NLR in the patient group compared with the control group and in patients with active disease compared with patients in remission. We evaluated their correlation with Kerr’s score, hs-CRP and ESR in the patient group. The results of our study suggest that a high PLR or NLR may indicate an increased inflammatory response associated with disease activity in patients with TAK.

bmjopen-2016-014451supp001.docx (38.3KB, docx)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: LP conceived the study, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. JD, HL and TL participated in the design of the study and helped to revise the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This project was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81400361). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. de Souza AW, de Carvalho JF. Diagnostic and classification criteria of Takayasu arteritis. J Autoimmun 2014;48-49:79–83. 10.1016/j.jaut.2014.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vaideeswar P, Deshpande JR. Pathology of Takayasu arteritis: a brief review. Ann Pediatr Cardiol 2013;6:52–8. 10.4103/0974-2069.107235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dogan S, Piskin O, Solmaz D, et al. Markers of endothelial damage and repair in Takayasu arteritis: are they associated with disease activity? Rheumatol Int 2014;34:1129–38. 10.1007/s00296-013-2937-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Erek Toprak A, Ozlu E, Uzuncakmak TK, et al. Neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio, serum endocan, and nesfatin-1 levels in patients with psoriasis vulgaris undergoing phototherapy treatment. Med Sci Monit 2016;22:1232–7. 10.12659/MSM.898240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ueno M Gao SQ, Huang LD, Dai RJ, et al. Neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: a controversial marker in predicting Crohn’s disease severity. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015;8:14779–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Uslu AU, Küçük A, Şahin A, et al. Two new inflammatory markers associated with disease activity Score-28 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio. Int J Rheum Dis 2015;18:731–5. 10.1111/1756-185X.12582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hu ZD, Sun Y, Guo J, et al. Red blood cell distribution width and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio are positively correlated with disease activity in primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Biochem 2014;47:287–90. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rifaioglu EN, Bülbül Şen B, Ekiz Ö, et al. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in Behçet’s disease as a marker of disease activity. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat 2014;23:65–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang F, Chen Z, Wang P, et al. Combination of platelet count and mean platelet volume (COP-MPV) predicts postoperative prognosis in both resectable early and advanced stage esophageal squamous cell cancer patients. Tumour Biol 2016;37:9323–31. 10.1007/s13277-015-4774-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Akboga MK, Canpolat U, Yuksel M, et al. Platelet to lymphocyte ratio as a novel indicator of inflammation is correlated with the severity of metabolic syndrome: a single center large-scale study. Platelets 2016;27:178–83. 10.3109/09537104.2015.1064518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Akboga MK, Canpolat U, Yayla C, et al. Association of platelet to lymphocyte ratio with inflammation and severity of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Angiology 2016;67:89–95. 10.1177/0003319715583186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Habets KL, Trouw LA, Levarht EW, et al. Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies contribute to platelet activation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:209 10.1186/s13075-015-0665-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aksu K, Donmez A, Keser G. Inflammation-induced thrombosis: mechanisms, disease associations and management. Curr Pharm Des 2012;18:1478–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Antiplatelet therapy in the treatment of takayasu arteritis. Circ J 2010;74:1079–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jiang L, Li D, Yan F, et al. Evaluation of Takayasu arteritis activity by delayed contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Cardiol 2012;155:262–7. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kasuya N, Kishi Y, Isobe M, et al. P-selectin expression, but not GPIIb/IIIa activation, is enhanced in the inflammatory stage of Takayasu’s arteritis. Circ J 2006;70:600–4. 10.1253/circj.70.600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Akazawa H, Ikeda U, Yamamoto K, et al. Hypercoagulable state in patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. Thromb Haemost 1996;75:712–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Keser G, Direskeneli H, Aksu K. Management of Takayasu arteritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology 2014;53:793–801. 10.1093/rheumatology/ket320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Souza AW, Machado NP, Pereira VM, et al. Antiplatelet therapy for the prevention of arterial ischemic events in Takayasu arteritis. Circ J 2010;74:1236–41. 10.1253/circj.CJ-09-0905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peredo R, Vilá S, Goñi M, et al. Reactive thrombocytosis: an early manifestation of Takayasu arteritis. J Clin Rheumatol 2005;11:270–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaplan MJ. Role of neutrophils in systemic autoimmune diseases. Arthritis Res Ther 2013;15:219 10.1186/ar4325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Surmiak M, Hubalewska-Mazgaj M, Wawrzycka-Adamczyk K, et al. Neutrophil-related and serum biomarkers in granulomatosis with polyangiitis support extracellular traps mechanism of the disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016;34(3 Suppl 97):98–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kolls JK, Lindén A. Interleukin-17 family members and inflammation. Immunity 2004;21:467–76. 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Arnaud L, Haroche J, Mathian A, et al. Pathogenesis of Takayasu’s arteritis: a 2011 update. Autoimmun Rev 2011;11:61–7. 10.1016/j.autrev.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Verri WA, Souto FO, Vieira SM, et al. IL-33 induces neutrophil migration in rheumatoid arthritis and is a target of anti-TNF therapy. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1697–703. 10.1136/ard.2009.122655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014451supp001.docx (38.3KB, docx)