Abstract

Objective

To examine the association between early-life exposure to the Chinese famine and the risk of chronic lung diseases in adulthood.

Design

Data analysis from a cross-sectional survey.

Setting and participants

4135 subjects were enrolled into the study from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) 2011–2012 baseline survey to analyse the associations between prenatal and early postnatal famine exposure and the risk of chronic lung diseases in adulthood.

Main outcome measures

Chronic lung diseases were defined based on self-reported information.

Results

The prevalence of self-reported chronic lung diseases in fetus-exposed, infant-exposed, preschool-exposed, and non-exposed groups was 6.5%, 7.9%, 6.8%, and 6.1%, respectively. The risk of chronic lung diseases in the infant-exposed group was significantly higher (OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.10 to 3.44) than the non-exposed group in severely affected areas, even after adjusting for gender, smoking, and drinking, family economic status, and the highest educational attainment of the parents (OR 2.57, 95% CI 1.26 to 5.25). In addition, after stratification by gender and famine severity, we found that only infant exposure to the severe famine was associated with the elevated risk of chronic lung diseases among male adults (OR 3.16, 95% CI 1.17 to 8.51).

Conclusions

Severe famine exposure during the period of infancy might increase the risk of chronic lung diseases in male adults.

Keywords: Famine, Developmental Origins of Health and Disease, Chronic Lung Diseases, Infant

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study evaluated the associations between prenatal and early postnatal exposure to the Chinese famine and the risk of chronic lung diseases in adulthood, which were unclear in previous studies.

The present study used the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study 2011-2012 baseline survey that covered all geographical regions in China, and was broadly representative of the entire mainland of China, and found infant exposure to the severe Chinese famine increased the risk of chronic lung diseases in male adults.

Selection bias was unavoidable, because severe famine could eliminate the weaker participants while leaving the healthier participants to survive, which may decrease the real effects of famine exposure.

Self-reported prevalence based on doctor diagnosis could be lower than the real prevalence of chronic lung diseases, and could underestimate the effects of famine exposure.

Introduction

The chronic lung diseases briefly include chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD), chronic bronchitis, bronchial asthma, and lung-heart disease (excluding lung tumours). The Global Status Report on Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) showed that respiratory diseases, including asthma and COPD, were the third leading cause of death from NCDs in 2012 (about four million).1 In low and middle income countries in particular, the burden of chronic lung diseases was heavier than in developed countries.2

The Development of Health and Disease (DoHaD) theory speculates that the fetus in utero changes its growth rate to adapt to the conditions regarding the availability of nutrients and oxygen to the mother. However, several studies had found that these adaptive changes might permanently modify the structure and physiological function of the fetus.3 4 The heavier lung disease burden in lower and middle income countries might be associated with a higher prevalence of low birth weight than in developed countries. Several studies had found that low birth weight was a strong factor for predicting a reduction in forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and forced vital capacity(FVC).5–7 Moreover, although some studies found that low birth weight increased the risk of asthma8–12 and mortality from COPD,7 no consistent results had been observed in previous studies.13–16

Due to ethical limitations, we cannot perform similar research in human beings, but natural historical famines have provided us with a unique opportunity to examine the DoHaD hypothesis in humans. The Dutch famine occurred in the west of the Netherlands at the end of the second world war, and lasted for about 6 months. One study observed that mid-gestation exposure to the Dutch famine increased significantly the prevalence of obstructive airways diseases in adulthood.17 The Chinese famine happened in the east of Asia, starting at the end of 1950 and ending in the early 1960s, a duration of about 3 years. A majority of studies have found that early-life exposure to the Chinese famine was linked with hypertension,18 diabetes,19 and metabolic syndrome20 in adulthood, but the associations with chronic lung diseases are still unclear.

In the current study, we used the public data of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) 2011–2012 baseline survey to examine the association between exposure to the Chinese famine in early life and the prevalence of chronic lung diseases in adulthood, and to explore whether these associations are gender-specific.

Methods

Sampling and participants

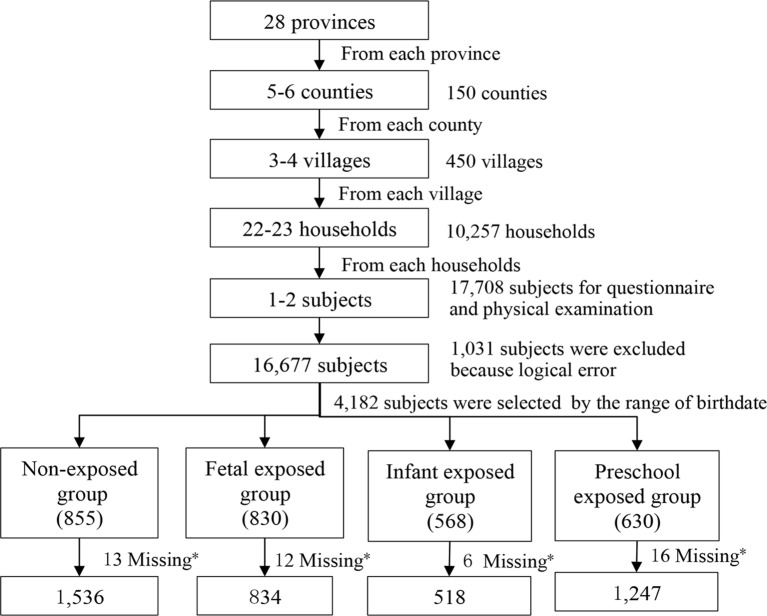

Sampling in the present study was based on a national population-based longitudinal survey (CHARLS 2011–2012).21 A total of 17 708 adults aged ≥45 years old from 10 257 households were randomly selected to receive the household survey, which was conducted among 150 counties, 28 provinces, and autonomous regions of mainland China; 4182 participants out of the 17 708 adults were screened by birth date and enrolled in the present study. After excluding 47 subjects who were missing information about chronic lung diseases, 4135 subjects were enrolled into our final analysis (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart on the sample selecting methods at each step. *Information about chronic lung diseases was missing in the raw database.

Sampling and grouping

Participants were divided into the non-exposed group and three famine-exposed groups (fetus, infant, and preschool-exposed). The Chinese famine began in January 1959 and ended in October 1961. In order to minimise the misclassification of the famine exposure, we defined the participants born between 1 October 1962 and 30 September 1964 as the non-exposed group; the participants born between 1 October 1 1959 and 30 September 1961 as the fetal-exposed group; the participants born between 1 January 1958 and 31 December 1958 as the infant-exposed group; and the participants born between 1 January 1956 and 31 December 1957 as the preschool-exposed group.

Famine severity

The severity of the famine in mainland China varied across the provinces due to differences in regional climate, population density and local food policies. Similar to previous studies,18 19 we compared the excess mortality during 1959–1961 with the mortality during 1956–1958 to evaluate of the severity of the famine in the present study; 100% was used as the threshold of excess mortality to distinguish the severity of famine exposure. The regions with excess mortality ≥100% were categorised as the severely affected areas, with the remainder categorised as less severely affected areas.

Measurements

Diagnosis of chronic lung diseases

In this study, data were collected through a household survey by investigators who received unified training and passed the examination. The diagnosis of chronic lung diseases was based on the question: ‘Have you been diagnosed with chronic lung diseases, such as chronic bronchitis, emphysema (excluding tumours, or cancer) by a doctor?’ Subjects answering ‘Yes’ were defined as suffering from chronic lung diseases, and subjects answering ‘No’ as not suffering from chronic lung diseases.

Assessment of covariates

Social demographic information, family economic status, the highest educational attainment of the parents, and lifestyle information including smoking and drinking status, were collected during face-to-face in-house interviews conducted by trained interviewers. The highest educational attainment of parents was categorised into four levels: primary school or below, junior school, senior school, and college or above. Smoking status was classified into never smoking, former smoking, and current smoking (who smoked at least one cigarette per day in the last year). Drinking status was classified into never drinking, former drinking, and current drinking (who drank at least once per week in the last year). The mean income level of the present sample (12 744 Chinese Yuan per person per year) was used as the cut-off point for family economic status (high vs low income).

Analysis

Statistical analyses were preformed using IBM SPSS 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous and categorical variables were expressed as mean±SD and per cent (%), respectively.

The χ2 test was used to compare the difference in the prevalence of chronic lung diseases between the non-exposed group and the famine-exposed group.

Univariate and multivariable logistic regression models by the maximum likelihood method were used to examine the risk of chronic lung diseases among the fetus, infant, and preschool-exposed groups, compared with the non-exposed group, respectively. In the multivariable logistic regression model, we adjusted for gender, smoking, drinking, family economic status, and the highest educational attainment of the parents. Interactions between famine-exposed groups (fetus, infant or preschool vs non-exposed) and areas (severely affected vs less severely affected) were tested by adding a multiplicative factor in the logistic regression model.

In order to explore whether there was a gender difference, stratified analysis by gender was performed using the same methods. Data were expressed as OR and 95% CI.

A two-sided p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant for all the analysis.

Ethics

Our study is a secondary analysis of the de-identified CHARLS public data. The Medical Ethics Committee of Peking University granted the current study exemption from review. All the subjects were informed and consented for the protocol of the study.

Results

The basic characteristics of participants are shown in table 1. A total of 4135 participants were enrolled into the present study. The sample sizes of the non-exposed, fetus, infant, and preschool-exposed groups were 1536, 834, 518, and 1247, respectively. The prevalence of chronic lung diseases for the non-exposed, fetus, infant, and preschool exposed groups were 6.1%, 6.5%, 7.9%, and 6.8%, respectively. We did not observe a statistically significant difference in the prevalence of chronic lung diseases among the four groups (p=0.511).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of study population according to exposure to the Chinese famine

| Variables | Non-exposed group | Fetal-exposed group | Infant-exposed group | Preschool-exposed group | p Value |

| Birth date | 10/1/1962– 9/30/1964 |

10/1/1959– 9/30/1961 |

19581/1/– 12/31/1958 |

1/1/1956- 12/31/1957 |

|

| N | 1536 | 834 | 518 | 1247 | |

| Age in 2011 (years) | 47~49 | 50~51 | 53 | 54~55 | |

| Born in severely affected area, n (%) | 657 (42.8) | 269 (32.3) | 192 (37.1) | 482 (38.7) | p<0.001 |

| Women, n (%) | 801 (52.2) | 438 (52.6) | 241 (46.5) | 614 (49.3) | p=0.067 |

| Smoking, n (%) | p=0.014 | ||||

| Never | 970 (66.4) | 519 (65.1) | 297 (61.4) | 711 (59.8) | |

| Former | 80 (5.5) | 36 (4.5) | 28 (5.8) | 77 (6.5) | |

| Current | 410 (28.1) | 242 (30.4) | 159 (32.9) | 400 (33.7) | |

| Drinking, n (%) | p=0.614 | ||||

| Never | 948 (61.8) | 513 (61.6) | 320 (61.9) | 787 (63.2) | |

| Less than once per month | 155 (10.1) | 82 (9.8) | 53 (10.3) | 100 (8.0) | |

| More than once per month | 430 (28.0) | 238 (28.6) | 144 (27.9) | 359 (28.8) | |

| Family income, n (%) | p=0.960 | ||||

| High | 199 (54.4) | 115 (53.5) | 65 (52.4) | 143 (52.4) | |

| Low | 167 (45.6) | 100 (46.5) | 59 (47.6) | 130 (47.6) | |

| Education, n (%) | p=0.390 | ||||

| Primary school and below | 695 (89.7) | 396 (89.8) | 246 (88.8) | 567 (92.5) | |

| Junior school | 40 (5.2) | 27 (6.1) | 16 (5.8) | 25 (4.1) | |

| High school | 31 (4.0) | 12 (2.7) | 10 (3.6) | 19 (3.1) | |

| College and above | 9 (1.2) | 6 (1.4) | 5 (1.8) | 2 (0.3) | |

| Prevalence of chronic lung disease (%) | 6.1 | 6.5 | 7.9 | 6.8 | p=0.511 |

Stratified analysis by famine severity is shown in table 2. Compared with the non-exposed group, only the prevalence of chronic lung diseases for the infant-exposed group was significantly higher in severely affected areas (5.6% vs 10.4%). Stratified by severity of famine exposure, we found that subjects in the infant-exposed group were at a higher risk of chronic lung diseases than the non-exposed group in severely affected areas (OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.10 to 3.44), even after adjusting for gender, smoking, drinking, family economic status, and the highest educational attainment (OR 2.57, 95% CI 1.26 to 5.25). However, we did not observe the consistent associations in other famine-exposed groups and in less severely affected areas. In addition, we did not observe any significant interactions between famine exposure groups (fetus, infant, or preschool vs non-exposed) and areas (severely affected vs less severely affected).

Table 2.

Risk of chronic lung diseases among three exposed groups compared with the non-exposed group

| Variables | Non-exposed group | Fetal-exposed group | Infant-exposed group | Preschool-exposed group |

| Severely affected famine area | ||||

| Prevalence (%) | 5.6 | 5.6 | 10.4 | 5.6 |

| p* | 0.973 | 0.022 | 0.983 | |

| OR (95% CI)* | Ref. | 0.99 (0.53 to 1.84) | 1.95 (1.10 to 3.44) | 0.99 (0.60 to 1.66) |

| p† | 0.953 | 0.009 | 0.437 | |

| OR (95% CI)† | Ref. | 0.98 (0.43 to 2.20) | 2.57 (1.26 to 5.25) | 0.75 (0.36 to 1.56) |

| Less severely affected famine area | ||||

| Prevalence (%) | 6.4 | 6.9 | 6.4 | 7.6 |

| p* | 0.691 | 0.964 | 0.336 | |

| OR (95% CI)* | Ref. | 1.09 (0.71 to 1.66) | 1.01 (0.60 to 1.70) | 1.21 (0.82 to 1.76) |

| p† | 0.254 | 0.398 | 0.471 | |

| OR (95% CI)† | Ref. | 1.38 (0.79 to 2.41) | 1.33 (0.69 to 3.56) | 1.22 (0.71 to 2.10) |

| p for interaction between area and group* | Ref. | 0.468 | 0.109 | 0.178 |

| p for interaction between area and group† | Ref. | 0.421 | 0.061 | 0.223 |

*Single variance binary logistic regression model.

†Multivariable logistic regression model, adjusted for gender, smoking, drinking, family economic status and the highest educational attainment of parents.

Table 3 presents the results of stratified analysis by gender and famine severity. In males, we observed that the infant-exposed group (OR 3.16, 95% CI 1.17 to 8.51) significantly increased the risk of chronic lung diseases in severely affected areas, compared with the non-exposed group. The consistent associations were not observed in fetal and preschool-exposed groups and in less severely affected areas. In females, we did not observe any significant associations between the famine exposed groups and the non-exposed group. Any significant interactions were not observed between the famine exposed groups (fetus, infant, or preschool vs non-exposed) and areas (severely affected vs less severely affected), for neither males nor females. The effects of the main covariates, including smoking, drinking, parents' educational attainment, and family economic status, on chronic lung diseases are shown in Supplementary Table 1 , stratified by gender and severity.

Table 3.

Prevalence rate of chronic lung diseases by gender, birth group and severity of the Chinese famine area

| Variables | Non-exposed group | Fetal-exposed group | Infant-exposed group | Preschool-exposed group |

| Female | ||||

| Severely affected area | ||||

| Prevalence (%) | 5.0 | 5.3 | 7.5 | 4.7 |

| p* | 0.907 | 0.359 | 0.861 | |

| OR (95% CI)* | Ref. | 1.05 (0.44 to 2.50) | 1.53 (0.62 to 3.81) | 0.93 (0.43 to 2.03) |

| p† | 0.514 | 0.208 | 0.479 | |

| OR (95% CI)† | Ref. | 1.39 (0.52 to 3.74) | 1.98 (0.68 to 5.72) | 0.67 (0.23 to 2.01) |

| Less severely affected area | ||||

| Prevalence (%) | 6.9 | 7.0 | 4.1 | 9.4 |

| p* | 0.970 | 0.218 | 0.176 | |

| OR (95% CI)* | Ref. | 1.01 (0.57 to 1.81) | 0.57 (0.23 to 1.39) | 1.41 (0.86 to 2.32) |

| p† | 0.238 | 0.644 | 0.359 | |

| OR (95% CI)† | Ref. | 1.55 (0.75 to 3.23) | 0.77 (0.24 to 2.39) | 1.40 (0.68 to 2.89) |

| p for interaction between area and group* | Ref. | 0.498 | 0.252 | 0.036 |

| p for interaction between smoking and group* | Ref. | 0.907 | 0.003 | 0.028 |

| p for interaction between area and group† | Ref. | 0.686 | 0.179 | 0.132 |

| p for interaction between smoking and group† | Ref. | 0.999 | 0.614 | 0.0.628 |

| Male | ||||

| Severely affected area | ||||

| Prevalence (%) | 6.3 | 5.9 | 13.1 | 6.5 |

| p* | 0.897 | 0.030 | 0.930 | |

| OR (95% CI)* | Ref. | 0.94 (0.39 to 2.29) | 2.26 (1.08 to 4.73) | 1.03 (0.52 to 3.03) |

| p† | 0.677 | 0.023 | 0.686 | |

| OR (95% CI)† | Ref. | 0.75 (0.20 to 2.87) | 3.16 (1.17 to 8.51) | 0.81 (0.30 to 2.22) |

| Less severely affected area | ||||

| Prevalence (%) | 5.8 | 6.9 | 8.4 | 5.7 |

| p* | 0.566 | 0.237 | 0.974 | |

| OR (95% CI)* | Ref. | 1.20 (0.64 to 2.24) | 1.50 (0.77 to 2.93) | 0.99 (0.55 to 1.80) |

| p† | 0.584 | 0.178 | 0.853 | |

| OR (95% CI)† | Ref. | 1.28 (0.53 to 3.07) | 1.82 (0.76 to 4.36) | 1.08 (0.45 to 2.60) |

| p for interaction between area and group* | Ref. | 0.734 | 0.217 | 0.709 |

| p for interaction between smoking and group* | Ref. | 0.409 | 0.300 | 0.207 |

| p for interaction between area and group† | Ref. | 0.344 | 0.127 | 0.887 |

| p for interaction between smoking and group† | Ref. | 0.950 | 0.103 | 0.696 |

*Single variance binary logistic regression model.

†Multivariable logistic regression model, adjusted for smoking, drinking, family economic status and the highest educational attainment of parents.

bmjopen-2016-015476supp001.pdf (86.8KB, pdf)

Discussion

In the current study, we observed that infant exposure to the Chinese famine significantly increased the risk of chronic lung diseases in later life. After stratifying by gender and famine severity, we found that only infant exposure to severe famine significantly increased the risk of chronic lung diseases in male adults, indicating that the infant period might be critical for human lung structure and function development.

Several mechanisms could explain the associations. (1) Early-life exposure to severe famine might perpetually modify bronchial reactivity during rapid growth. One Dutch famine study found that exposure to famine during gestation affected neither the concentrations of total or specific IgE nor lung function values (FEV1 and FVC), but they observed a significant association between exposure to famine in mid and early gestation and obstructive airways disease in adulthood.17 The results indicated that famine exposure might not change the lung function and atopic disease, but could permanently modify the bronchial responsiveness. Although we could not make this assumption because bronchial reactivity was not measured in our study, this assumption may be one way to explain the mechanism. (2) Severe malnutrition during early life might increase susceptibility to pulmonary injury in later life. An animal model study found that young animals who were exposed to a low protein maternal diet as a fetus were more likely to suffer pulmonary injury than non-exposed young animals, which indicated programming of the antioxidant defences and immune system.22 Another animal study reported that fetuses exposed to a low protein diet significantly decreased the binding of dexamethasone to lung receptors.23

The present study further added new direct evidence in human beings for the fetal origin of diseases. To our knowledge, only one Dutch study explored the associations between early-life exposure to famine and atopy, lung function and obstructive airways disease, and found that famine exposure in mid and early gestation might significantly increase the prevalence of obstructive airways disease. Results of this Dutch study are inconsistent with the current study's findings. In this study, we found that only severe famine exposure in the infant stage significantly increased the risk of chronic lung diseases in adulthood. Several reasons could explain the difference. First, race might be a major reason for the difference between the two studies. Subjects in the Dutch study were white European, while subjects in this study were Asian. Second, the severity and duration of the famine could be another important discrepancy. The Dutch famine lasted for about 6 months, while the Chinese famine lasted for about 3 years. Furthermore, the Chinese famine led to approximately 30 million premature deaths.24 However, the mortality rate during the Dutch famine period (in 1945) was more than twice as high as that in 1939, and most of the excess mortality was attributed to severe malnutrition.25

Interestingly, we observed that severe famine exposure during the infant period significantly increased the risk of chronic lung diseases among men, but not among women, which seems to be contradictory to the severity of famine exposure. Chinese parents have a profound and enduring tradition of ‘preferring boys to girls’, and thus boys may have been better protected against the famine by their parents. This is inconsistent with metabolic syndrome.26 We speculate that the development of boys' lungs could be more sensitive to severe malnutrition in early life; however, the specific mechanisms need to be further explored in a future study.

There are several limitations to this study. The primary limitation is selection bias. Severe famine could eliminate weaker participants, so that only the healthier participants remain, which may decrease the real effect of famine exposure. Second, similar to other Chinese famine studies,18 19 27 the present study lacked the objective indicators that reflect the severity of famine exposure, for example, birth weight, birth body length. Thirdly, because both bad weather and infection in early-life could increase the risk of chronic lung diseases, we cannot attribute all the excess mortality rate to the famine exposure. In addition, we cannot separate the effect of age from famine exposure. Despite these limitations, the present study used data from the CHARLS 2011–2012 baseline survey that has broad representation of the entire mainland of China, and found that infant exposure to severe famine significantly increased the risk of chronic lung diseases among men.

Conclusions

Infant exposure to severe famine could increase the risk of chronic lung diseases in male adults, indicating that the infant stage might be the critical period of lung development in men.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the team of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) 2011–2012 baseline survey. We are grateful to all the participants who took part in the baseline survey, and we also acknowledge all the subjects and households that participated in the survey for their cooperation.

Footnotes

Contributors: JM and ZW were co-investigators and designed the study, ZW, ZZ, ZY and YD carried out the initial analysis, and supervised data analysis. All authors were involved in writing the paper and had final approval of the submitted and published versions.

Funding: This work was supported by National Science Foundation of China (NSFC 81402692).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Medical Ethics Committee of Peking University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets analyzed in the current study are available online (http://charls.pku.edu.cn/zh-CN/page/data/2011-charls-wave1).

Reference

- 1. Zhou M, Wang H, Zhu J, et al. . Cause-specific mortality for 240 causes in China during 1990-2013: a systematic subnational analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 2016;387:251–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00551-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2015;386:743–800. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Li J, Na L, Ma H, et al. . Multigenerational effects of parental prenatal exposure to famine on adult offspring cognitive function. Sci Rep 2015;5:13792 10.1038/srep13792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wadhwa PD, Buss C, Entringer S, et al. . Developmental origins of health and disease: brief history of the approach and current focus on epigenetic mechanisms. Semin Reprod Med 2009;27:358–68. 10.1055/s-0029-1237424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Stein CE, Kumaran K, Fall CH, et al. . Relation of fetal growth to adult lung function in south India. Thorax 1997;52:895–9. 10.1136/thx.52.10.895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rona RJ, Gulliford MC, Chinn S. Effects of prematurity and intrauterine growth on respiratory health and lung function in childhood. BMJ 1993;306:817–20. 10.1136/bmj.306.6881.817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Barker DJ, Godfrey KM, Fall C, et al. . Relation of birth weight and childhood respiratory infection to adult lung function and death from chronic obstructive airways disease. BMJ 1991;303:671–5. 10.1136/bmj.303.6804.671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shaheen SO, Sterne JA, Montgomery SM, et al. . Birth weight, body mass index and asthma in young adults. Thorax 1999;54:396–402. 10.1136/thx.54.5.396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Slezak JA, Persky VW, Kviz FJ, et al. . Asthma prevalence and risk factors in selected Head Start sites in Chicago. J Asthma 1998;35:203–12. 10.3109/02770909809068208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schaubel D, Johansen H, Dutta M, et al. . Neonatal characteristics as risk factors for preschool asthma. J Asthma 1996;33:255–64. 10.3109/02770909609055366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oliveti JF, Kercsmar CM, Redline S. Pre- and perinatal risk factors for asthma in inner city African-American children. Am J Epidemiol 1996;143:570–7. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Arshad SH, Stevens M, Hide DW. The effect of genetic and environmental factors on the prevalence of allergic disorders at the age of two years. Clin Exp Allergy 1993;23:504–11. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1993.tb03238.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shaheen SO, Sterne JA, Tucker JS, et al. . Birth weight, childhood lower respiratory tract infection, and adult lung function. Thorax 1998;53:549–53. 10.1136/thx.53.7.549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sears MR, Holdaway MD, Flannery EM, et al. . Parental and neonatal risk factors for atopy, airway hyper-responsiveness, and asthma. Arch Dis Child 1996;75:392–8. 10.1136/adc.75.5.392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Matthes JW, Lewis PA, Davies DP, et al. . Birth weight at term and lung function in adolescence: no evidence for a programmed effect. Arch Dis Child 1995;73:231–4. 10.1136/adc.73.3.231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kelly YJ, Brabin BJ, Milligan P, et al. . Maternal asthma, premature birth, and the risk of respiratory morbidity in schoolchildren in Merseyside. Thorax 1995;50:525–30. 10.1136/thx.50.5.525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lopuhaä CE, Roseboom TJ, Osmond C, et al. . Atopy, lung function, and obstructive airways disease after prenatal exposure to famine. Thorax 2000;55:555–61. 10.1136/thorax.55.7.555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li Y, Jaddoe VW, Qi L, et al. . Exposure to the Chinese famine in early life and the risk of hypertension in adulthood. J Hypertens 2011;29:1085–92. 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328345d969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Li Y, He Y, Qi L, et al. . Exposure to the Chinese famine in early life and the risk of hyperglycemia and type 2 diabetes in adulthood. Diabetes 2010;59:2400–6. 10.2337/db10-0385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Li Y, Jaddoe VW, Qi L, et al. . Exposure to the Chinese famine in early life and the risk of metabolic syndrome in adulthood. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1014–8. 10.2337/dc10-2039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhao Y, Hu Y, Smith JP, et al. . Cohort profile: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). Int J Epidemiol 2014;43:61–8. 10.1093/ije/dys203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Langley-Evans SC, Phillips GJ, Jackson AA. Fetal exposure to low protein maternal diet alters the susceptibility of young adult rats to sulfur dioxide-induced lung injury. J Nutr 1997;127:202–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mulay S, Browne CA, Varma DR, et al. . Placental hormones, nutrition, and fetal development. Fed Proc 1980;39:261–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cai Y, Feng W, Famine FW. Famine, social disruption, and involuntary fetal loss: evidence from Chinese survey data. Demography 2005;42:301–22. 10.1353/dem.2005.0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Banning C. Food shortage and public health, first half of 1945. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 1946;245:93–110. 10.1177/000271624624500114 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zheng X, Wang Y, Ren W, et al. . Risk of metabolic syndrome in adults exposed to the great Chinese famine during the fetal life and early childhood. Eur J Clin Nutr 2012;66:231–6. 10.1038/ejcn.2011.161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wang Z, Li C, Yang Z, et al. . Infant exposure to Chinese famine increased the risk of hypertension in adulthood: results from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. BMC Public Health 2016;16:435 10.1186/s12889-016-3122-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-015476supp001.pdf (86.8KB, pdf)