Abstract

Introduction

Ankle fracture surgery is a common procedure, but the influence of anaesthesia choice on postoperative pain and quality of recovery is poorly understood. Some authors suggest a benefit of peripheral nerve block (PNB) in elective procedures, but the different pain profile following acute fracture surgery and the rebound pain on cessation of the PNB both remain unexplored. We present an ongoing randomised study aiming to compare primary PNB anaesthesia with spinal anaesthesia for ankle fracture surgery regarding postoperative pain profiles and quality of recovery.

Methods and analysis

AnAnkle Trial is a randomised, dual-centre, open-label, blinded analysis trial of 150 adult patients undergoing primary internal fixation of an ankle fracture. Main exclusion criteria are habitual opioid use, impaired pain sensation, other painful injuries or cognitive impairment. The intervention is ultrasound-guided popliteal sciatic (20 mL) and saphenal nerve (8 mL) PNB with ropivacaine 7.5 mg/mL, and controls receive spinal anaesthesia (2 mL) with hyperbaric bupivacaine 5 mg/mL. Postoperatively all receive paracetamol, ibuprofen and patient-controlled intravenous morphine on demand. Morphine consumption and pain scores are registered in the first 27 hours and reported as an integrated pain score as the primary endpoint. Pain score intervals are 3 hours and we will use the area under curve to get a longitudinal measure of pain. Secondary outcomes include rebound pain on cessation of anaesthesia, opioid side effects (Opioid-Related Symptom Distress Scale), quality of recovery (Danish Quality of Recovery-15 score) and pain scores and medication days 1–7 (diary).

Ethics and dissemination

The study has been approved by the Regional Ethics Committees in the Capital Region of Denmark, the Danish Data Protection Agency and the Danish Health and Medical Authority. We will publish the results in international peer-reviewed medical journals.

Trial registration number

AnAnkle Trial is registered in the European Clinical Trials Database (EudraCT 2015-001108-76).

Keywords: Peripheral nerve block, regional anaesthesia, ankle fracture, postoperative pain, rebound pain

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first trial to thoroughly investigate the postoperative pain profile and directly compare the most commonly used regional anaesthesia techniques for ankle fracture surgery.

The trial is randomised and designed with attention to allocation concealment and stratification to prevent selection bias.

The primary endpoint is a composite measure of pain and morphine consumption, which holds more statistical power than when analysing either of the two components alone.

Blinding of participants and investigators is not feasible; thus, the trial is open-labelled with blinded data analysis.

Introduction

Peripheral nerve blocks (PNB) are getting increasingly popular for both primary anaesthesia and postoperative pain control in orthopaedic limb surgery, but its suitability for acute fracture surgery is not well established.

Ankle fracture is a common acute condition, which often requires surgery.1 2 There is no evidence-based consensus regarding the best choice of anaesthesia modality for this high-volume procedure, and the influence of this choice on the postoperative pain profile is poorly understood. Spinal anaesthesia (SA) is most common, but PNBs are becoming widely implemented, as they provide long-lasting pain control and are regarded very safe.3–7 There is some evidence that PNBs used in elective surgical procedures on knee, ankle and foot are effective in reducing pain, opioid consumption and related side effects such as nausea and vomiting, as well as potentially reducing length of hospital stay and increasing patient satisfaction.4 8–16 However, PNBs can represent a logistical challenge in the acute setting and, moreover, the pain profile following fractures and fracture surgery is naturally different from that of conditions requiring elective surgery.

Very few studies have investigated the efficacy and possible benefits of PNBs in this context and results are incongruous. One randomised study of postoperative pain scores in ankle fracture surgery showed initial benefit with PNB added to general anaesthesia but also revealed a sizeable ‘rebound pain’ on cessation of the PNBs, which could challenge the overall benefit on the postoperative pain profile.17 Another randomised study of bimalleolar fracture surgery patients showed a longer postoperative effect of PNB anaesthesia compared with SA measured as time to first analgesic request, but pain levels were not measured.18 At our centre, a large retrospective study of postoperative opioid consumption in ankle fracture surgery has suggested that the largest benefit of the regional anaesthesia modalities is obtained with PNBs.19 However, in a prospective exploratory pilot study investigating primary PNB anaesthesia for ankle fracture surgery, we also found a clear indication of rebound pain in relation to cessation of the PNB effect, especially in younger individuals (abstract published).20

We hypothesise the following:

PNB anaesthesia for ankle fracture surgery reduces overall postoperative pain, opioid use and opioid-related side effects compared with SA.

Rebound pain following cessation of PNB anaesthesia is more pronounced than rebound pain following cessation of SA after ankle fracture surgery.

Patient-reported quality of recovery after ankle fracture surgery is better following PNB anaesthesia than following SA.

We therefore aim to assess the postoperative pain profile and quality of recovery after acute ankle fracture surgery in a randomised setting comparing primary PNB anaesthesia with SA.

Methods and analysis

Trial design

AnAnkle Trial is a prospective, randomised, parallel group, dual-centre, open-label, blinded analysis trial designed to assess the postoperative pain profile and quality of recovery following ankle fracture surgery under PNB anaesthesia compared with SA. The study is conducted in two university hospitals in the Capital Region of Denmark. Trial participants are randomly assigned to either SA or PNB anaesthesia as described below. Primary data are patient-reported pain scores and on demand morphine consumption reported as an integrated pain score (IPS).

Participant eligibility and consent

Treating physicians consecutively identify eligible subjects according to the listed criteria. Eligible subjects receive written and oral information and are included after anaesthesiologist investigators have obtained informed written consent.

Inclusion criteria

Scheduled for internal fixation of an ankle fracture.

Age >18 years.

Ability to read and understand Danish and give informed written consent.

Exclusion criteria

Allergy towards non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, paracetamol, morphine or local anaesthetics.

Bodyweight <52 kg to avoid toxic doses of local anaesthetics.

Contraindications for SA.

Current gastrointestinal bleeding.

Proximal fibular fracture or multitrauma/other simultaneous fractures.

Cognitive or psychiatric dysfunction or alcohol/narcotic substance abuse causing expected inability to comply with study protocol.

No available anaesthesiologist with PNB capability at scheduled time of operation.

Neuropathy/neurological dysfunction in the lower extremities.

Habitual daily use of opioids.

Pregnancy or breast feeding.

Infection at anaesthesia injection site.

Nephropathy requiring dialysis.

Acute porphyria.

Recruitment period

All legislative and ethical approvals were obtained and the trial registered in the European Clinical Trials Database (EudraCT 2015-001108-76) by June 2015.21 22 Inclusion was initiated in July 2015 and will continue until 150 patients have been included and their primary outcome data secured in an expected inclusion period of 22–24 months.

Sample size estimation

The target sample size for AnAnkle Trial is 150 participants. This estimation for the primary outcome (IPS) is based on the O’Brien Castello formula by calculating Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney odds (WMW odds) for sample sizing in non-parametric statistics.23 24 Prior studies have shown a positive correlation between the two parameters on which the IPS is based, that is, higher pain scores are associated with a higher opioid consumption and vice versa.23 Using data from our observational study, we designed the trial to be able to detect a simultaneous 30% difference in both morphine consumption and pain scores as we consider this a clinically meaningful difference. We did not plan any interim analyses.

This results in WMW odds=1.75. With a power of 80% (β=20%) and two-sided significance level α=5%, the resulting sample size is 141 patients. Adding 6% to adjust for protocol violations results in a final sample size of 150 (2×75) patients to include.

We also conducted sample size estimations for the following key secondary outcomes, which were all found to be covered by the set sample size: numeric rating scale pain score area under the curve (NRS-AUC) for a rebound period of 6 hours with 50% intergroup difference; rebound IPS of 6 hours with 30% difference; NRS-AUC of 0–27 hours with 30% difference; morphine consumption of 0–27 hours with 30% difference; and quality of recovery score with 10% difference. All outcomes are listed below.

Randomisation and allocation concealment

Randomisation is externally managed, computer-generated and irreversible. The allocation and participant trial identification number is retrieved via a secured website, with an allocation ratio of 1:1 between PNB and SA. The sequence is stratified by trial centre and patient age group (≤60 or >60 years of age) and performed as block randomisation with variable block sizes that are unknown to the investigators to maintain allocation concealment. We thereby follow the International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) guideline for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and minimise possible bias from uneven inclusion between centres and age groups with potentially different pain profiles.

Blinding

The trial is open-labelled. Thus, investigators and participants are not blinded, but data will be blinded by an independent consultant before analysis.

The difference in anaesthesia application between the groups (spinal in the lower back and PNB at lower thigh level) combined with the characteristic differences in onset and duration of anaesthesia makes blinding of both participants and physicians administering the anaesthesia effectively impossible. PNBs must be administered well before the surgery to ensure sufficient onset time, whereas SA is best administered shortly before surgery to ensure adequate duration. A clear difference in duration of the anaesthesia effect between groups is expected, which renders blinding of data collectors ineffective. Data for the main outcomes are registered directly by the participants (pain scores) or electronically (morphine patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump). Patients do not need to consult with staff to take morphine. The collected data will be anonymised and blinded by an external consultant, not otherwise involved in the trial, before statistical analysis is performed.

Interventions

Intervention group: PNB as ultrasound-guided popliteal sciatic nerve block and midfemoral saphenal nerve block with ropivacaine hydrochloride 7.5 mg/mL. We use a fixed dose of 20 mL (150 mg) for the sciatic nerve and 8 mL (60 mg) for the saphenal nerve to minimise the risk of toxic reactions. Unsuccessful block of a single nerve (tibial, peroneal or saphenal), defined as no effect on sensory function after 40–45 min or insufficient effect after 60 min, is supplemented with an additional dose of 5 mL or 10 mL provided the patient is weighing 62–71 kg or >72 kg, respectively, thus staying within recommended total dosage of 4 mg/kg of ropivacaine.

Control group: standard SA using hyperbaric bupivacaine 5 mg/mL, 2.0 mL.

Both groups: small doses of midazolam, propofol or similar can be offered on demand during administration of spinal or PNB anaesthesia to help remedy any anxiety. Both groups will be offered light to moderate sedation during the operation with intravenous propofol. If necessary, intravenous boluses of short-action opioid such as fentanyl or sufentanil can be administered.

Standard postoperative pain medication regimen: tablet paracetamol 1000 mg ×4, tablet ibuprofen 400 mg ×3 and intravenous morphine via a PCA pump system delivering 2.5 mg of morphine on demand with a 6 min lockout period. The morphine is changed to tablets 5–10 mg on demand after 27 hours.

Outcomes

Primary outcome measure

IPS for the period 0–27 hours postanaesthesia. IPS is based on NRS-AUC and total morphine consumption. NRS pain score is registered every 3 hours.

The 27-hour primary study period was defined from experiences gained in the observational pilot study to ensure that we capture the full period of potential rebound pain in both groups. The PNBs lasted a mean of 16.5 hours, and rebound pain stabilised and subsided within a maximum of about 6 hours. We chose time of anaesthesia as starting point rather than time of surgery because logistical challenges can result in fairly large variations in time from PNB administration to surgery.

Secondary outcome measures

Rebound pain: IPS for a 6-hour period from patient-reported time of cessation of the sensory block (PNB or spinal) in the ankle.

NRS-AUC pain 0–27 hours postanaesthesia.

Morphine use 0–27 hours (PCA pump).

Opioid adverse effects 0–27 hours: clinically meaningful events (CME) assessed with the composite Opioid-Related Symptom Distress Scale (OR-SDS).25 26

Quality of recovery (Danish Quality of Recovery-15 score)27 0–27 hours.

‘Risk patients’, that is, number of patients with IPS +100 to +200 (=high pain and high morphine consumption).

Peak NRS pain score 0–27 hours.

‘High pain patients’, that is, number of patients reaching peak NRS ≥7.

Tertiary outcome measures

NRS pain scores postoperative (PO) days 1–7.

Need for on-demand opioids PO days 2–7.

Opioid adverse effects PO day 2: CMEs assessed by the composite OR-SDS score.

Overall patient satisfaction with anaesthesia form including postoperative pain control, NRS score.

Adverse events/adverse reactions (AEs).

Postoperative nerve-related symptoms on PO day 7.

The OR-SDS questionnaire has been validated in English.25 26 28 We conducted a Danish translation for AnAnkle Trial using two independent medical doctors, bilingual in English and Danish. Disagreements were discussed with the principal investigator, and minor adjustments were made in a second round after testing the translated version on eight patients.

Data management, audit and safety

Only data necessary for evaluation of the stated outcomes, safety parameters and possible confounders are collected, and only after inclusion and randomisation on retrieving informed written consent.

For every included patient, a case report form is devised for registration of all data except morphine use, which is electronically registered by the PCA pump and saved as patient-specific files. Data sources include patient-reported pain scores, questionnaires and diary, electronic patient files and the PCA morphine data files. The NRS pain scores are registered directly by the patients on paper. They also note the time of return of sensation to the ankle.

All data are marked and handled according to GCP standards and legislative permission by the Danish Data Protection Agency.

Safety

Any AEs within five half-lives of the intervention drugs are registered and classified using the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events.29 All severe AEs (SAEs) are reported to the responsible trial sponsor and followed until stabilised or resolved. If an SAE meets the criteria for reporting, it is forwarded immediately to the Danish Medicines Agency and the Ethics Committee.

The trial will be stopped in its entirety in the unlikely event that incidence and severity of AEs compromise the safety of trial participants as evaluated by the trial group or by the Danish Medicines Agency.

AnAnkle Trial is monitored by the independent GCP unit at Copenhagen University Hospital through regular auditing visits to both trial centres, thus ensuring adherence to GCP guidelines as well as proper handling and reporting of AEs.

Protocol violations and participant withdrawal

Protocol violations

Failed spinal or PNB (defined as change of anaesthesia modality necessary).

Glucocorticoids or controlled-release opioids administered on the day of surgery.

Participants meeting any one of these criteria will not be excluded and data are collected as planned. Data will be included in an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis but omitted in per-protocol analyses.

Participant withdrawal

Participants can be withdrawn/excluded after randomisation if:

Surgery is cancelled after administration of anaesthesia. The patient can be reincluded later if possible.

Surgery is rescheduled or changed after randomisation and eligibility is no longer upheld according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Postoperative complications make the patient unable to comply with study protocol for obtaining primary data (pain scores and PCA morphine data for 27 hours).

Withdrawal of consent, before all primary data are obtained (pain scores and PCA morphine data for 27 hours).

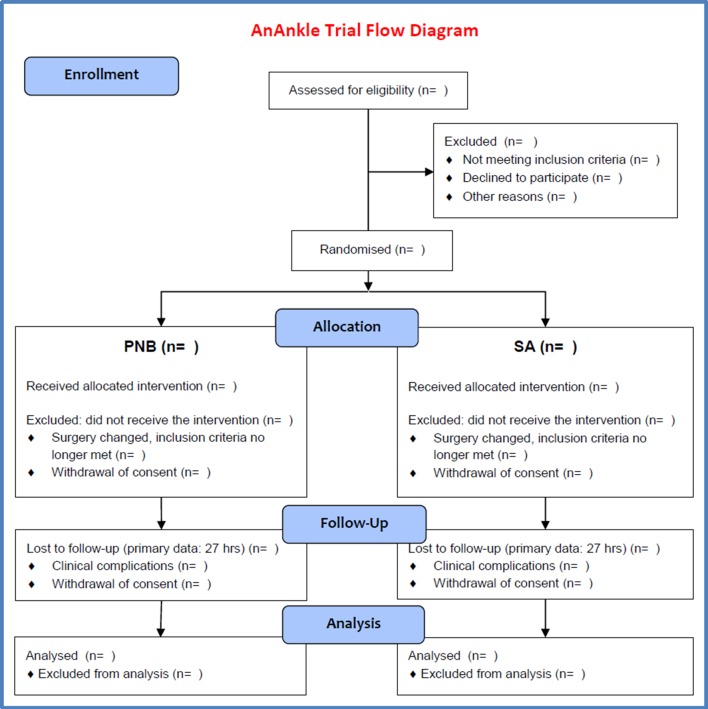

Participants meeting any of these criteria can be excluded from the trial after randomisation. No data will be analysed and they will be replaced by additional inclusion until the calculated sample size is included for ITT analysis. For safety reasons AEs will be registered for any excluded patients who have received the intervention (anaesthesia). An overview is shown in the flow diagram (figure 1).

Figure 1.

AnAnkle Trial flow diagram. PNB, peripheral nerve block; SA, spinal anaesthesia.

Withdrawal of consent or failure to comply with the protocol after 27 hours postoperatively will not lead to exclusion from analysis of already collected data.

Statistical plan

Primary outcome analysis

Pain scores and morphine data cannot be expected to follow normal distribution, and we expect to handle the primary outcome using non-parametric statistics. The IPS has been validated statistically with this in mind.23 It is derived from pain scores (NRS-AUC in our trial) and total morphine consumption. Both measures are ranked across both trial groups, and the IPS is calculated as deviation from mean rank in pain score added to deviation from mean rank in morphine, giving a result for each trial participant between −200% and +200%. The groups can be compared for significant difference with a distribution-independent permutation test and/or Mann-Whitney test, and effect size can be expressed by the ratio of mean rank or WMW odds.23

Analysis of the primary outcome will be performed as ‘intention-to-treat’ analysis including all consenting randomised patients not meeting the defined withdrawal criteria. Additional ‘per-protocol’ analyses will be performed and include only participants who follow the protocol without the defined protocol violations.

Two-sided p values <0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Secondary outcome analyses

Again, we expect to handle most outcomes using non-parametric statistics. However, some results such as NRS-AUC measures may prove to resemble a normal distribution which, taken together with the fairly large sample size, warrants the use of parametric tests in order to obtain CIs on these estimates. In parametric models, we may include adjustment for expected heavy confounders, that is, age, diabetes and fracture severity (unimalleolar, bimalleolar or trimalleolar), as this can increase the accuracy of the estimate, even though the groups are expected to be comparable due to randomisation.

Subgroup analyses

Pain experience is known to vary with age and possibly gender.30 We have stratified randomisation in two age groups (≤60 or >60 years of age) and will perform subgroup analysis on relevant outcomes according to age group and gender.

Accountability procedure for missing data for analysis

Data for the primary outcome are registered from 0 to 27 hours from time of anaesthesia. Missing data after this time (until the end of participation on postoperative day 7) will not be replaced.

Some missing data are expected in the patient-reported NRS pain scores from 0 to 27 hours. Pragmatically we will fill in a missing measure point with the average of the two adjacent points, in effect drawing a line between them (linear interpolation), and thus allowing for AUC to be calculated. If the missing point is the last one (at 27 hours), the value of the last observation is carried forward. If more than two 0–27 hours NRS scores are missing, the patient will be excluded from per-protocol analyses.

The measuring of rebound pain is performed over a period of 6 hours following patient-evaluated cessation of the sensory block. Should this period extend beyond the 27-hour period, we will carry forward the last observation to extrapolate data. As the mean effect duration of the PNBs in our observational study was around 16 hours, we do not expect that extrapolation will be necessary. When appropriate, we will perform sensitivity analyses to evaluate the impact of data extrapolation.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical and legislative approvals

AnAnkle Trial is conducted in accordance with applicable regulatory requirements and the study protocol, which is approved by the Regional Ethics Committees in the Capital Region of Denmark, the Danish Data Protection Agency and the Danish Health and Medical Authority. We follow national and international standards for good clinical practice (ICH GCP guidelines) and the recommendations of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) Statement and extension in reporting randomised clinical pragmatic trials.31 The protocol was drafted following the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) guidelines accordingly (see online supplementary data 1).32 The project is monitored by the Copenhagen GCP unit.

bmjopen-2017-016001supp001.pdf (130.4KB, pdf)

Publication plan

We strive to readily publish the results in international peer-reviewed journals, and all the results will be made public, regardless of whether they come out positive, negative or inconclusive. Due to the complexity of the pain profiles, we intend to publish the results in at least two independent articles, with focus on the primary outcome measure and the secondary measure of rebound pain, respectively.

All authors must fulfil the criteria of the Vancouver convention.

Discussion

Regional anaesthesia is often preferred in ankle fracture surgery due to the superior safety profile and probably better postoperative pain control compared with general anaesthesia.17 19 33 To the best of our knowledge, AnAnkle Trial is the first study to thoroughly investigate the postoperative pain profile and test which one of the most frequently used regional anaesthesia techniques is superior. Postoperative pain studies are often limited by large time intervals between pain registrations. We designed our trial to avoid this issue since it renders evaluation of the clinical significance of rebound pain impossible, because the rebound could be very intense yet completely undetected in-between pain scorings.

AnAnkle Trial constitutes a scientifically strong set-up, although blinding of the participants and investigators is not practically possible, which holds a potential risk of bias; for example, reported pain scores might be affected by psychological factors influenced by information from the investigators. To minimise this influence, all pain scores used for the primary outcome are registered by the participants, without consulting the staff. Likewise, the morphine data are gathered electronically from the PCA pump, which the patient activates without consulting the staff, thus ensuring a minimal risk of related bias. Finally, data analysis will be blinded. As in most other clinical trials, there remains a risk of sampling bias due to the eligibility criteria, which might impair the overall generalisability of our results.

Among the strengths of the design are randomisation and attention to sequence generation and allocation concealment to prevent selection bias between the two groups. The block randomisation and stratification protect against bias from variability of practice during a relatively long inclusion period on different centres. We have chosen a composite score of pain assessment and opioid consumption as primary outcome. The IPS has been thoroughly tested and proven to hold more statistical power than conventional comparisons of pain scores or morphine alone.23 There is a natural correlation between the two that can lead to failure in identifying a true effect, or even lead to finding a false-positive effect, on either outcome, when not balanced by evaluation of the other. In this study we will use the IPS with a longitudinal pain measurement in the form of AUC pain score rather than a single pain rating. This allows us to illustrate the pain profile over time without letting the results be compromised by statistical mass significance. The individual components of the IPS are separately analysed among various secondary endpoints to provide supplementary details to the composite primary endpoint, as is recommended in the Initiative on Methods, Measurement, and Pain Assessment in Clinical Trials (IMMPACT) consensus on pain trials.34

If AnAnkle Trial yields clear results, the implications on clinical practice could be profound. Fracture surgery is very common and optimising the choice of anaesthesia will have a major influence on the postoperative recovery and the overall patient course for a very large group of patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jesper Kent Nielsen, MD, Consultant Anaesthetist, Herlev and Gentofte University Hospital, Herlev, Denmark, and Nicolai Bang Foss, MD, DMSc, Consultant Anaesthetist, Hvidovre and Amager Hospital, Hvidovre, Denmark, for valuable input during idea development and drafting of the protocol. We thank biostatistician Tobias Wirenfeldt Klausen, MSc, Department of Haematology, Herlev and Gentofte Hospital, Herlev, Denmark, for statistical assistance, and we thank OPEN Odense Patient data Explorative Network, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark, for the secure online randomisation solution.

Footnotes

Contributors: RS: Idea development, study planning, writing first draft, revisions, approving final protocol, registering and obtaining legislative and ethical approvals.

SB, IG, AMM: Idea development, study planning, draft revisions, approving final protocol.

Funding: This study is supported by the non-profit Danish Society of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine 'DASAIMs Forskningsinitiativ', the private non-profit foundation 'Viggo og Krista Pedersens Fond' and by the public source 'Forskningsrådet Herlev Hospital'. The first author is the sponsor; the funders have no role in design, conduction or analysis of this trial.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained from patients.

Ethics approval: The Regional Ethics Committees in the Capital Region of Denmark.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Daly PJ, Fitzgerald RH, Melton LJ, et al. Epidemiology of ankle fractures in Rochester, Minnesota. Acta Orthop Scand 1987;58:539–44. 10.3109/17453678709146395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Court-Brown CM, McBirnie J, Wilson G. Adult ankle fractures--an increasing problem? Acta Orthop Scand 1998;69:43–7. 10.3109/17453679809002355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Watts SA, Sharma DJ. Long-term neurological complications associated with surgery and peripheral nerve blockade: outcomes after 1065 consecutive blocks. Anaesth Intensive Care 2007;35:24–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Klein SM, Nielsen KC, Greengrass RA, et al. Ambulatory discharge after long-acting peripheral nerve blockade: 2382 blocks with ropivacaine. Anesth Analg 2002;94:65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jeng CL, Torrillo TM, Rosenblatt MA. Complications of peripheral nerve blocks. Br J Anaesth 2010;105 (Suppl 1):i97–i107. 10.1093/bja/aeq273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Capdevila X, Pirat P, Bringuier S, et al. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in hospital wards after orthopedic surgery: a multicenter prospective analysis of the quality of postoperative analgesia and complications in 1,416 patients. Anesthesiology 2005;103:1035–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sites BD, Taenzer AH, Herrick MD, et al. Incidence of local anesthetic systemic toxicity and postoperative neurologic symptoms associated with 12,668 ultrasound-guided nerve blocks: an analysis from a prospective clinical registry. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2012;37:478–82. 10.1097/AAP.0b013e31825cb3d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Capdevila X, Barthelet Y, Biboulet P, et al. Effects of perioperative analgesic technique on the surgical outcome and duration of rehabilitation after Major knee surgery. Anesthesiology 1999;91:8–15. 10.1097/00000542-199907000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Elliot R, Pearce CJ, Seifert C, et al. Continuous infusion versus single bolus popliteal block following Major ankle and hindfoot surgery: a prospective, randomized trial. Foot Ankle Int 2010;31:1043–7. 10.3113/FAI.2010.1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. White PF, Issioui T, Skrivanek GD, et al. The use of a continuous popliteal sciatic nerve block after surgery involving the foot and ankle: does it improve the quality of recovery? Anesth Analg 2003;97:1303–9. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000082242.84015.D4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liu SS, Strodtbeck WM, Richman JM, et al. A comparison of regional versus general anesthesia for ambulatory anesthesia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Anesth Analg 2005;101:1634–42. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000180829.70036.4F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grosser DM, Herr MJ, Claridge RJ, et al. Preoperative lateral popliteal nerve block for intraoperative and postoperative pain control in elective foot and ankle surgery: a prospective analysis. Foot Ankle Int 2007;28:1271–5. 10.3113/FAI.2007.1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Xu J, Chen X, Ma C, et al. Peripheral nerve blocks for postoperative pain after major knee surgery Wang X, ed Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2014. CD010937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chan E-Y, Fransen M, Parker DA, et al. Femoral nerve blocks for acute postoperative pain after knee replacement surgery Chan E-Y, ed Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Chichester, UK:: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2014. CD009941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Casati A, Cappelleri G, Berti M, et al. Randomized comparison of remifentanil-propofol with a sciatic-femoral nerve block for out-patient knee arthroscopy. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2002;19:109–14. 10.1017/S0265021502000194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jankowski CJ, Hebl JR, Stuart MJ, et al. A comparison of psoas compartment block and spinal and general anesthesia for outpatient knee arthroscopy. Anesth Analg 2003;97:1003–9. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000081798.89853.E7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Goldstein RY, Montero N, Jain SK, et al. Efficacy of popliteal block in postoperative pain control after ankle fracture fixation: a prospective randomized study. J Orthop Trauma 2012;26:557–61. 10.1097/BOT.0b013e3182638b25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Protić A, Horvat M, Komen-Usljebrka H, et al. Benefit of the minimal invasive ultrasound-guided single shot femoro-popliteal block for ankle surgery in comparison with spinal anesthesia. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2010;122:584–7. 10.1007/s00508-010-1451-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Christensen KP, Møller AM, Nielsen JK, et al. The effects of Anesthetic Technique on Postoperative opioid consumption in ankle fracture surgery. Clin J Pain 2016;32:870–4. 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sort R, Brorson S, Gögenur I, et al. Peripheral nerve block in primary ankle fracture surgery - exploring rebound pain. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2015;32:88.25058504 [Google Scholar]

- 21. The European Medicines Agency. EudraCT public website: EMA; https://eudract.ema.europa.eu/. [Google Scholar]

- 22. The European Medicines Agency. EU clinical trials Register. https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/.

- 23. Dai F, Silverman DG, Chelly JE, et al. Integration of pain score and morphine consumption in analgesic clinical studies. J Pain 2013;14:767–77. 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Noether GE. Sample size determination for some Common Nonparametric tests. J Am Stat Assoc 1987;82:645–7. 10.1080/01621459.1987.10478478 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chan KS, Chen WH, Gan TJ, et al. Development and validation of a composite score based on clinically meaningful events for the opioid-related symptom distress scale. Qual Life Res 2009;18:1331–40. 10.1007/s11136-009-9547-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yadeau JT, Liu SS, Rade MC, et al. Performance characteristics and validation of the Opioid-Related symptom distress Scale for evaluation of analgesic side effects after orthopedic surgery. Anesth Analg 2011;113:369–77. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31821ae3f7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kleif J, Edwards HM, Sort R, et al. Translation and validation of the Danish version of the postoperative quality of recovery score QoR-15. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2015;59:912–20. 10.1111/aas.12525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Apfelbaum JL, Gan TJ, Zhao S, et al. Reliability and validity of the perioperative opioid-related symptom distress scale. Anesth Analg 2004;99:699–709. 10.1213/01.ANE.0000133143.60584.38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. National Institute of Cancer. Common Terminology Criteria for adverse events (CTCAE). NIH Publ 2010;2009:0–71. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ip HY, Abrishami A, Peng PW, et al. Predictors of postoperative pain and analgesic consumption: a qualitative systematic review. Anesthesiology 2009;111:657–77. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181aae87a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010;340:c869 10.1136/bmj.c869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jordan C, Davidovitch RI, Walsh M, et al. Spinal anesthesia mediates improved early function and pain relief following surgical repair of ankle fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92:368–74. 10.2106/JBJS.H.01852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Turk DC, Dworkin RH, McDermott MP, et al. Analyzing multiple endpoints in clinical trials of pain treatments: immpact recommendations. Pain 2008;139:485–93. 10.1016/j.pain.2008.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016001supp001.pdf (130.4KB, pdf)