Abstract

Introduction

Gout and hyperuricaemia are major health issues and relevant guidance documents have been released by a variety of national and international organisations. However, these documents contain inconsistent recommendations with unclear quality profiles. We aim to conduct a systematic appraisal of the clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements pertaining to the diagnosis and treatment for hyperuricaemia and gout, and to summarise recommendations.

Methods

We will search PubMed, EMBASE and guideline databases to identify published clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements. We will search Google and Google Scholar for additional potentially eligible documents. The quality of included guidelines and consensus statements will be assessed using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) II instrument and be presented as scores. We will also manually extract recommendations for clinical practice from all included documents.

Ethics and dissemination

The results of this systematic review will be disseminated through relevant conferences and peer-reviewed journals.

Protocol registration number

PROSPERO CRD42016046104.

Keywords: Clinical practice guideline, Hyperuricemia, Gout, Systematic review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This proposed study is the first systematic review to assess the quality of clinical guidance documents on the diagnosis and treatment for hyperuricaemia and gout in English literature.

The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II instrument is used for evaluation, which is an international, validated and rigorously developed tool.

Only guidance documents in English and Chinese are included.

Introduction

Gout is a major health problem worldwide, with the prevalence varying from 0.1% to 10% in different regions.1 The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007–2008 showed that among adults aged over 20 years in the United States, 3.9% had self-reported gout, while only 2.9% of the population reported gout in the 1988–1994 survey.2 As in mainland China, a systematic review of data from 2000 to 2014 suggested the prevalence of hyperuricaemia and gout in the general population were 13.3% and 1.1%, respectively.3 In general, both developed and developing countries presented with increasing prevalence and incidence of gout in recent decades.1

Patients with hyperuricaemia or gout are at risk of developing a variety of comorbidities, such as hypertension,4 5 chronic kidney disease,6 cardiovascular diseases,7 8 metabolic syndromes9 10 and psychiatric disorders.11 A recent survey found that 5%–10% of patients with gout had at least seven comorbidities and that hypertension was presented in at least 74% patients with gout.12 13 These comorbid conditions add difficulties to gout management and affect patients’ quality of life.

Evidence-based, accurate and timely guidance documents are important for clinical practice. They enhance the delivery of high-quality care and consequently improve overall patient outcomes. Guidelines for hyperuricaemia and gout are published by academies of rheumatology, endocrinology, cardiology and nephrology. Of these, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines,14 15 updated in 2012, and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) guidelines,16–18 updated in 2016, have the strongest global influence. Additionally, a multinational collaboration involving practising rheumatologists throughout the world, the 3e (Evidence, Expertise, Exchange) Initiative, released its guidance document in 2014.19 Moreover, a variety of countries developed national guidance for clinical practice, such as China,20 Italy,21 Japan,22 Malaysia,23 the United Kingdom24–26 and so forth.

However, despite the availability of various guidance documents, the adherence of physicians and patients to guideline recommendations was poor.27 28 One possible reason was the inconsistency of recommendations between different guidelines,29 despite their shared general principles. The most discussed inconsistency is the timing to initiate urate lowering therapy (ULT) in patients with acute gout attack. The guidelines released by the British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology,26 by the Japanese Society of Gout and Nucleic Acid Metabolism22 and by the Rheumatologic Associates of Long Island30 all emphasised that pharmacological ULT should never be initiated during acute attacks because the change of serum urate level during an attack could exacerbate the condition. However, the ACR guideline14 suggested that pharmacological ULT could be started during an acute gout attack as long as anti-inflammatory management was effective. In the meantime, the 3e Initiative guideline19 did not recommend a clear time to start ULT for an acute attack, and the latest EULAR guideline stated no specific guidance on the initiation of ULT whether during a flare or 2 weeks after its termination.18

Inconsistencies also lie in several other aspects. The cut-off uric acid level for hyperuricaemia diagnosis varies from 6.1 mg/dL to 7.0 mg/dL.14 20 22 30 Although the target serum urate level is generally set as 6 mg/dL14 18 19 26 30 or below, which is lower than the saturation point for monosodium urate (6.8 mg/dL), the exact targets recommended by different guidelines are diverse. Furthermore, the 2016 updated EULAR guideline paid additional attention to its lower limit, stating that serum urate below 3 mg/dL was not recommended for long-term management.18 As for managing asymptomatic patients with hyperuricaemia without comorbidities, the 2006 EULAR17 and the 3e Initiative19 guidelines did not recommend pharmacological ULT regardless of the serum urate level, while a guideline from the Japanese society suggested application of ULT with a target uric acid of below 8 mg/dL.22 The 2016 update of the EULAR guideline highlighted the concept of early initiation of ULT, although the Task Force admitted the lack of adequate clinical evidence.18 The consensus from the Chinese Society of Endocrinology suggested that the adoption of pharmacological ULT in asymptomatic patients should be dependent on cardiovascular risks and serum uric acid level.20 As for ULT options, the ACR guideline14 recommended both allopurinol and febuxostat as first line options, without prioritisation, while the EULAR guideline18 and the 3e Initiative guideline19 suggested febuxostat as an alternative only for patients intolerant of or not responding to allopurinol. In the meantime, the Chinese consensus20 suggested that drugs promoting the excretion of uric acid, such as benzbromarone, were most widely used, because the majority of hyperuricaemic cases were caused by uric acid underexcretion instead of overproduction.

These inconsistencies among guidance documents may result from ethnical and social differences, however, can also be consequences of non-standard developing processes. Low-quality guidelines affect the outcomes of patients and the compliance of practitioners to guidance documents. Hence, we will conduct this study to evaluate the guidance documents on gout and hyperuricaemia.

Objective

The aim of this protocol study is to explore the quality and consistency of published guidance documents for the diagnosis and treatment of hyperuricaemia and gout using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) tool.

Methods

This protocol is developed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses for Protocols (PRISMA-P)31 32 and is registered with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42016046104). A PRISMA-P checklist is provided as an online supplementary document.

bmjopen-2016-014928supp001.pdf (184.2KB, pdf)

Inclusion/exclusion criteria for study selection

We will include international and national/regional clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements for the diagnosis and/or treatment of both hyperuricaemia and gout. We define clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements as documents providing recommendations for patient care, which are derived from a systematic review of existing evidence or from collective opinions of an expert panel.33 A document will be included if it: (1) is presented as a clinical practice guideline or a consensus statement; (2) specifically provides recommendations for diagnosis and/or management for hyperuricaemia or gout; (3) is produced by related professional associations, institutes, societies, or communities for national or international use; (4) is published in English or Chinese.

The exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) original investigation, study protocols, comments on existing guidelines or consensus, and conference abstracts or posters; (2) draft documents that are under development or not finalised; (3) previous documents replaced by updated versions from the same organisation.

Search strategies

We will search PubMed, EMBASE and guideline databases from the inception of the database for guidelines pertaining to the diagnosis and treatment of hyperuricaemia and gout. Guideline databases to be searched include the National Guideline Clearinghouse (NGC),34 the Guidelines International Network (GIN),35 the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) website,36 the National Health Service (NHS) Evidence website,37 the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) website,38 the Guidelines and Audit Implementation Network (GAIN),39 the Turning Research Into Practice Database (TRIP),40 the Epistemonikos,41 the Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM)42 and the Wanfang database.43 The search strategy was developed in consultation with a librarian and will be tailored in different databases. Combinations will be searched of the following keywords: ‘hyperuricemia’, ‘gout’, ‘uric acid’, ‘urate’, ‘guideline’, ‘consensus’, ‘statement’, ‘recommendation’, and ‘policy’. The draft search strategy for EMBASE using the OVID interface is provided as table 1. These strategies may be revised to improve sensitivity and specificity. Search results will be managed with the EndNote X6 reference manager (Thomson Reuters, New York, USA).

Table 1.

Sample search strategy for EMBASE using the OVID interface

| 1 | exp hyperuricaemia/ |

| 2 | exp gout/ |

| 3 | exp uric acid/ |

| 4 | exp urate/ |

| 5 | hyperuric?emia.m_titl. |

| 6 | gout.m_titl. |

| 7 | uric acid.m_titl. |

| 8 | urate$.m_titl. |

| 9 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 |

| 10 | exp practice guideline/ |

| 11 | guideline$.m_titl. |

| 12 | consensus.m_titl. |

| 13 | position statement$.m_titl. |

| 14 | exp health care policy/ or exp policy/ |

| 15 | recommendation$.m_titl. |

| 16 | 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 |

| 17 | 9 and 16 |

We will also conduct searches on Google44 and Google Scholar45 for potentially eligible guidelines and consensus statements that are not indexed in the aforementioned databases. We will search the internet via the Google Chrome browser using the strategy ‘region AND (hyperuricemia OR gout) AND (guideline OR consensus OR recommendation OR statement)’ and screen the first 100 records for each region. Names of regions to be searched are: the United States, Australia, Canada, China, Europe, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Singapore, South Africa and the United Kingdom. We will search via the Google Scholar engine using the strategy ‘(hyperuricemia OR gout) AND (guideline or consensus or recommendation or statement)’ and screen the first 200 records.

Study selection and data extraction

Two reviewers will independently screen the titles and abstracts of all searched documents and determine the papers for full-text review. Documents excluded during full-text review will be reported with reasons for exclusion. Disagreements will be resolved through discussion with a consultant endocrinologist.

We will extract the following data from each included document: document characteristics (eg, first author, year of publication, title, issuing organisation, country, funding body), recommendations for diagnosis and investigation of hyperuricaemia and gout, and recommendations for management (eg, treatment and prophylaxis for acute gout, ULT options, target serum uric acid levels, comorbidities).

Appraisal of guidance documents

All included documents will be assessed by four reviewers (QL, XL, JS-WK and SL) independently using the AGREE II instrument.46 AGREE II is an international, validated and rigorously developed tool to evaluate the quality of clinical practice guidelines47 48 and consensus statements.49 50 This tool is composed of 23 items and evaluates six domains of guideline development and report: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, and editorial independence. Reviewers score each item on a 7-point Likert Scale, with 1 point for strongly disagree and 7 points for strongly agree. The score for each domain of each document is calculated as follows: (obtained score−minimal possible score)/(maximal possible score−minimal possible score). The minimum possible score is calculated as: (number of questions) × (number of reviewers) × 1. The maximum possible score is calculated as: (number of questions) × (number of reviewers) × 7.46 This score calculation will be conducted using the My AGREE PLUS platform.51

All reviewers will complete the online training tutorial52 before the commencement of appraisal to ensure standardisation. A meeting will be held among reviewers after the appraisal and every item with scores differing more than 1 point will be discussed. Reviewers can revise their scores or keep the original evaluation after discussion, and records will be made for the scores revised with reasons for revision. When the scoring process is completed, the inter-rater reliability on AGREE II will be examined using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) via IBM SPSS (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA). An ICC ≥0.7 is considered acceptable.53

Recommendation synthesis

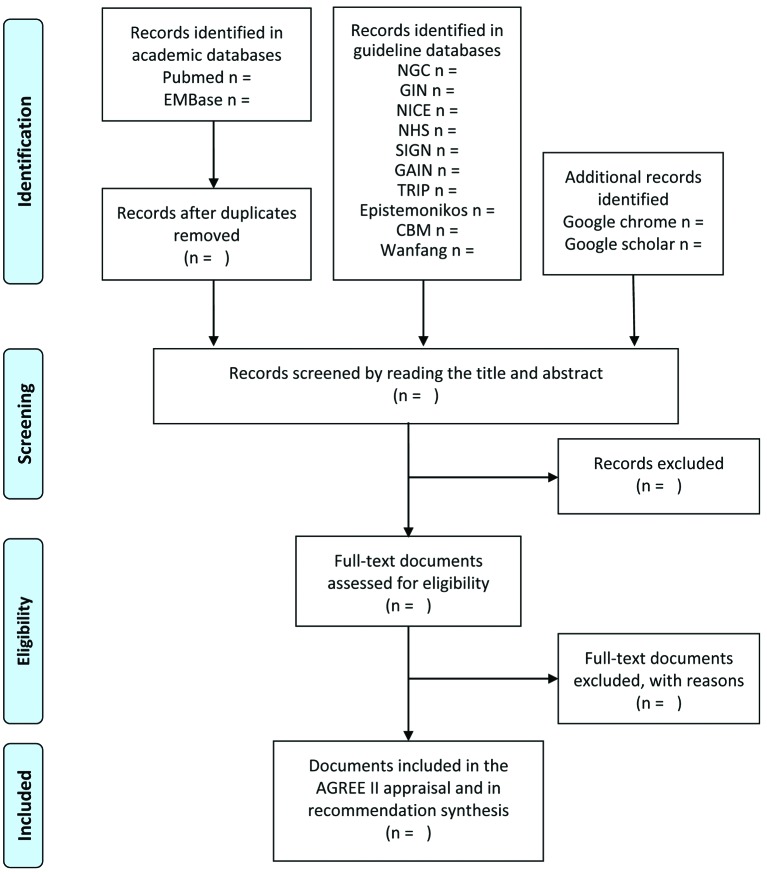

We will manually extract descriptive data from included documents and tabulate them to summarise recommendations of guidance documents and to highlight consistencies. The domains of recommendations summarised will depend on the information available in guidance documents relating to the diagnosis and treatment strategies for hyperuricaemia and gout, such as target uric acid level, timing to initiate ULT in patients with acute gout attack, prioritisation of ULT options, allopurinol dosing, prophylaxis management against acute gout attack, treatment for asymptomatic patients with hyperuricaemia without comorbidities, timing to assess urate deposits with imaging techniques and monitoring of urate deposits clearance. A flow diagram (figure 1) will be provided to illustrate the review process.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram for literature search. AGREE II, Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II; CBM, Chinese Biomedical Literature database; GAIN, Guidelines and Audit Implementation Network; GIN, Guidelines International Network; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NGC, National Guideline Clearinghouse; NHS, National Health Service; SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; TRIP, Turning Research Into Practice database.

Discussion

Clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements are of important value for clinical practice. However, guidance documents issued by different organisations for hyperuricaemia and gout are highly inconsistent, which impairs the application of and compliance to these documents. Hence, we will conduct this systematic review to identify the quality and consistency of guidelines and consensus, and provide a summary of guideline recommendations.

To date, no systematic appraisal for the quality of hyperuricaemia and gout guidelines has been reported in the English or Chinese literature. Although a quality appraisal54 of four recent guidelines for gout was published in 2014, it did not systematically review all published guidance documents. Additionally, only two appraisers were involved, one of which was a co-author of one of the rated guidelines, while the AGREE II developer recommends four appraisers.53 Our proposed review integrates comprehensive search strategies, applies the well-established and validated AGREE II tool and adopts a rigorous appraisal process by four independent reviewers to minimise subjective bias.

Possible limitations of this research are language restrictions and unconscious bias from subjective rating of documents. To minimise publication bias, we will search grey literature on the internet via Google and selection bias will be reduced by involving four independent reviewers.

It is necessary to systematically review and appraise clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements for diagnosis and management of hyperuricaemia and gout. This protocol provides a clear and structured process for guidance documents identification, quality evaluation and recommendation summarisation. This review will assist clinicians to better understand and apply guidelines and consensus recommendations to improve hyperuricaemia and gout care, guideline developers to develop guidance documents of high quality, and researchers to identify knowledge gaps for future research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms Peipei Liu, BSc, at Sichuan University Library for her help with developing the search strategy.

Footnotes

Contributors: HT and SL conceived this study. QL, JSWK and SL designed the inclusion/exclusion criteria and the searching resource and strategy. QL, JSWK, HC and XS designed the appraisal strategy of each included guideline and consensus. QL, XL and SL drafted the protocol. All authors discussed actively in the protocol of the study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: This manuscript is a protocol of a systematic review and does not contain original data.

References

- 1. Kuo CF, Grainge MJ, Zhang W, et al. . Global epidemiology of gout: prevalence, incidence and risk factors. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015;11:649–62. 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Zhu Y, Pandya BJ, Choi HK. Prevalence of gout and hyperuricemia in the US general population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007-2008. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:3136–41. 10.1002/art.30520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu R, Han C, Wu D, et al. . Prevalence of Hyperuricemia and Gout in Mainland China from 2000 to 2014: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:1–12. 10.1155/2015/762820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Taniguchi Y, Hayashi T, Tsumura K, et al. . Serum uric acid and the risk for hypertension and type 2 diabetes in Japanese men: The Osaka Health Survey. J Hypertens 2001;19:1209–15. 10.1097/00004872-200107000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rapado A. Relationship between gout and arterial hypertension. Adv Exp Med Biol 1974;41:451–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Juraschek SP, Kovell LC, Miller ER, et al. . Association of kidney disease with prevalent gout in the United States in 1988-1994 and 2007-2010. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2013;42:551–61. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clarson LE, Hider SL, Belcher J, et al. . Increased risk of vascular disease associated with gout: a retrospective, matched cohort study in the UK clinical practice research datalink. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:642–7. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-205252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lin KC, Tsao HM, Chen CH, et al. . Hypertension was the Major risk factor leading to development of cardiovascular diseases among men with hyperuricemia. J Rheumatol 2004;31:1152–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frank O. Observations concerning the incidence of disturbance of lipid and carbohydrate metabolism in gout. Adv Exp Med Biol 1974;41:495–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nyberg F, Horne L, Morlock R, et al. . Comorbidity Burden in Trial-Aligned Patients with Established Gout in Germany, UK, US, and France: a retrospective analysis. Adv Ther 2016;33:1180–98. 10.1007/s12325-016-0346-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Changchien TC, Yen YC, Lin CL, et al. . High risk of depressive disorders in patients with gout: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Medicine 2015;94:e2401 10.1097/MD.0000000000002401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pillinger MH, Goldfarb DS, Keenan RT. Gout and its comorbidities. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis 2010;68:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Torres RJ, de Miguel E, Bailén R, et al. . Tubular urate transporter gene polymorphisms differentiate patients with gout who have normal and decreased urinary uric acid excretion. J Rheumatol 2014;41:1863–70. 10.3899/jrheum.140126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Khanna D, Fitzgerald JD, Khanna PP, et al. . 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:1431–46. 10.1002/acr.21772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khanna D, Khanna PP, Fitzgerald JD, et al. . 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 2: therapy and antiinflammatory prophylaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:1447–61. 10.1002/acr.21773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhang W, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. . EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. part I: diagnosis. Report of a task force of the standing Committee for International clinical studies including therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1301–11. 10.1136/ard.2006.055251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang W, Doherty M, Bardin T, et al. . EULAR evidence based recommendations for gout. Part II: management. Report of a task force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1312–24. 10.1136/ard.2006.055269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Richette P, Doherty M, Pascual E, et al. . 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:29–42. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sivera F, Andrés M, Carmona L, et al. . Multinational evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of gout: integrating systematic literature review and expert opinion of a broad panel of rheumatologists in the 3e initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:328–35. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chinese society of Endocrinology. Chinese consensus statement on the management of hyperuricemia and gout. J Chines Endoc Metabol 2013;29. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Manara M, Bortoluzzi A, Favero M, et al. . Italian society of rheumatology recommendations for the management of gout. Reumatismo 2013;65:4–21. 10.4081/reumatismo.2013.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Yamanaka H. Japanese Society of Gout and Nucleic Acid Metabolism. Japanese guideline for the management of hyperuricemia and gout: second edition. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids 2011;30:1018–29. 10.1080/15257770.2011.596496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ministry of Health Malaysia. Management of Gout, 2008. http://moh.gov.my/attachments/3893.pdf (accessed 20 Aug 2016).

- 24. Lapraik C, Watts R, Bacon P, et al. . BSR and BHPR guidelines for the management of adults with ANCA associated vasculitis. Rheumatology 2007;46:1615–6. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem146a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stevenson M, Pandor A. Febuxostat for the treatment of hyperuricaemia in people with gout: a single technology appraisal. Health Technol Assess 2009;13:37–42. 10.3310/hta13suppl3/06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jordan KM, Cameron JS, Snaith M, et al. . British Society for Rheumatology and British Health Professionals in Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Rheumatology 2007;46:1372–4. 10.1093/rheumatology/kem056a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wise E, Khanna PP. The impact of gout guidelines. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2015;27:225–30. 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vargas-Santos AB, Castelar-Pinheiro GR, Coutinho ES, et al. . Adherence to the 2012 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) Guidelines for management of Gout: a survey of Brazilian rheumatologists. PLoS One 2015;10:e0135805 10.1371/journal.pone.0135805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Khanna PP, FitzGerald J. Evolution of management of gout: a comparison of recent guidelines. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2015;27:139–46. 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hamburger M, Baraf HS, Adamson TC, et al. . Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of gout and hyperuricemia. Postgrad Med 2011;2011:3–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Committee on Standards for Developing Trust. worthy Clinical Practice Guidelines, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine : Graham R, Mancher M, Wolman DM, Clinical Practice Guidelines We Can Trust. US: The National Academies Press, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Agency for Healthcare Research Quality. National Guidelines Clearinghouse. http://www.guideline.gov.

- 35. Guidelines International Network. www.g-i-n.net.

- 36. National Institute for Health for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). www.nice.org.uk.

- 37. National Health Service (NHS) Evidence. https://www.evidence.nhs.uk.

- 38. Scottish Intercollegiate guidelines Network (SIGN). http://sign.ac.uk/index.html.

- 39. Guidelines and Audit Implementation Network (GAIN). http://www.gain-ni.org/.

- 40. Turning Research Into Practice Database (TRIP). https://www.tripdatabase.com/.

- 41. Epistemonikos database. http://www.epistemonikos.org/.

- 42. SinoMed. Chinese Biomedical Literature Database. http://www.sinomed.ac.cn.

- 43. Wanfang Data. http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn.

- 44. Google. https://www.google.com.

- 45. Google Scholar. https://scholar.google.com/.

- 46. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. . AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ 2010;182:E839–E842. 10.1503/cmaj.090449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Deng Y, Luo L, Hu Y, et al. . Clinical practice guidelines for the management of neuropathic pain: a systematic review. BMC Anesthesiol 2016;16:12 10.1186/s12871-015-0150-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Huang TW, Lai JH, Wu MY, et al. . Systematic review of clinical practice guidelines in the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules and cancer. BMC Med 2013;11:191 10.1186/1741-7015-11-191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lopez-Olivo MA, Kallen MA, Ortiz Z, et al. . Quality appraisal of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements on the use of biologic agents in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1625–38. 10.1002/art.24207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nagler EV, Vanmassenhove J, van der Veer SN, et al. . Diagnosis and treatment of hyponatremia: a systematic review of clinical practice guidelines and consensus statements. BMC Med 2014;12:121 10.1186/s12916-014-0231-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. My AGREE PLUS platform. http://www.agreetrust.org/my-agree/.

- 52. AGREE II training tools. http://www.agreetrust.org/resource-centre/agree-ii-training-tooles/.

- 53. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. . Development of the AGREE II, part 1: performance, usefulness and areas for improvement. CMAJ 2010;182:1045–52. 10.1503/cmaj.091714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Nuki G. An appraisal of the 2012 American College of Rheumatology guidelines for the management of Gout. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2014;26:152–61. 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014928supp001.pdf (184.2KB, pdf)