Abstract

Objective

This study aimed to investigate the association between splenectomy and empyema in Taiwan.

Methods

A population-based cohort study was conducted using the hospitalisation dataset of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Program. A total of 13 193 subjects aged 20–84 years who were newly diagnosed with splenectomy from 2000 to 2010 were enrolled in the splenectomy group and 52 464 randomly selected subjects without splenectomy were enrolled in the non-splenectomy group. Both groups were matched by sex, age, comorbidities and the index year of undergoing splenectomy. The incidence of empyema at the end of 2011 was calculated. A multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to estimate the HR with 95% CI of empyema associated with splenectomy and other comorbidities.

Results

The overall incidence rate of empyema was 2.56-fold higher in the splenectomy group than in the non-splenectomy group (8.85 vs 3.46 per 1000 person-years). The Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed a higher cumulative incidence of empyema in the splenectomy group than in the non-splenectomy group (6.99% vs 3.37% at the end of follow-up). After adjusting for confounding variables, the adjusted HR of empyema was 2.89 for the splenectomy group compared with that for the non-splenectomy group. Further analysis revealed that HR of empyema was 4.52 for subjects with splenectomy alone.

Conclusion

The incidence rate ratio between the splenectomy and non-splenectomy groups reduced from 2.87 in the first 5 years of follow-up to 1.73 in the period following the 5 years. Future studies are required to confirm whether a longer follow-up period would further reduce this average ratio. For the splenectomy group, the overall HR of developing empyema was 2.89 after adjusting for age, sex and comorbidities, which was identified from previous literature. The risk of empyema following splenectomy remains high despite the absence of these comorbidities.

Keywords: empyema, splenectomy, Taiwan national health insurance program

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first original study on the association between splenectomy and empyema.

We used a hospitalisation dataset with a large sample size and great statistical power.

Some traditional behaviour risk factors including alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking were not recorded due to the inherent limitation of this insurance database.

This case–control study included only patients with splenectomy, which may limit the generalisability of the study results to the general population.

Such a study design does not permit to conclude a substantial causality.

Introduction

Pleural empyema is a suppurative infection of the pleural cavity. The aetiology of empyema is classified as two distinct mechanisms. Empyema most commonly occurs following pneumonia as microorganisms spread directly into the pleural cavity. This occurs in approximately 1%–5% of pneumonia cases.1 2 The second mechanism occurs following surgery, most commonly of the thorax, oesophagus, lung or heart. Although empyema is an ancient disease with centuries of learnt experience, it continues to be an important clinical problem. Despite the use of antibiotics and different pneumococcal vaccines, empyema remains the most common complication of pneumonia and is an important cause of morbidity worldwide.3 The development of antibiotics in the first half of the 20th century significantly contributed in decreasing the incidence of pleural infection. However, this trend shifted at the end of the 20th century, and the incidence of empyema has tended to increase worldwide.

The human spleen mainly serves as an immune responder against invading microorganisms.4 5 Immunological responses and haematological functions of the human spleen are well known. The spleen, mediated by the innate and adaptive immunity, protects the body against infections.6 7 Therefore, patients with splenectomy are more likely than those without splenectomy to develop severe life-threatening infections. Splenectomy is associated with an increased risk of some diseases, including pulmonary tuberculosis, type 2 diabetes mellitus, pyogenic liver abscess, renal and perinephric abscesses, and acute pancreatitis8–12; however, to our knowledge, postsplenectomy empyema has not yet been studied.

Despite the trend of increasing incidence of empyema worldwide, no study has evaluated the association between splenectomy and empyema. Here we rationally hypothesise an association between splenectomy and empyema owing to the immunocompromised condition induced by splenectomy, which can further increase the risk of microorganism invasion of the pleural cavity. However, there is limited published literature regarding epidemiological studies on this issue. As splenectomy is associated with overwhelming postsplenectomy infections and empyema carries potential fatality, exploring the risk of empyema in patients with splenectomy may have significant clinical and public health implications. Therefore, to explore whether an association between splenectomy and empyema exists, we conducted a nationwide cohort study using the hospitalisation dataset of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Program.

Methods

Study design and data source

Taiwan is an independent country with over 23 million people.13–17 We conducted a population-based cohort study using insurance claim data from the Taiwan National Health Insurance Program, which has covered 99% of the Taiwan population since 1995 and thus is a thorough representative sample of the population.18 The details of the insurance program have been well documented in previous studies.19–22 This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University and Hospital in Taiwan (CMUH-104-REC2-115).

Study subjects

Using the hospitalisation dataset of the Taiwan National Health Insurance Program, all hospitalised subjects aged 20–84 years who underwent splenectomy (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, ICD-9 procedure code 41.5) between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2010 were categorised in the splenectomy group. The year of undergoing splenectomy was defined as the index year. For each subject in the splenectomy group, four subjects who did not undergo splenectomy were randomly selected from the same database and were categorised in the non-splenectomy group. Both groups were matched with regard to sex, age (every 5-year span), comorbidities and the index year of undergoing splenectomy. To reduce potentially biased results, subjects with an empyema diagnosis (ICD-9 codes 510, 511.1, 511.8 and 511.9) within 1 month following splenectomy were excluded.

Outcome and comorbidities

The main outcome was a new diagnosis of empyema on the basis of hospital discharge registries during the follow-up period. Each subject was monitored from the index year until being diagnosed with empyema; being censored because of the loss to follow-up, death or withdrawal from insurance; or at the end of 31 December 2011, namely the end of the study. The following comorbidities were investigated: alcohol-related disease, cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease (including cirrhosis, alcoholic liver damage, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and other chronic hepatitis), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diabetes mellitus. All comorbidities were diagnosed according to the ICD-9 codes, which have been well assessed in previous studies.23–33

Statistical analysis

The differences between the splenectomy and non-splenectomy groups with respect to sex, age and comorbidities were compared using the χ2 test for categorical variables and t-test for continuous variables. The subject’s sex, age and follow-up period (in person-years) were used to estimate incidence rate and incidence rate ratio (IRR) of the splenectomy group to the non-splenectomy group with 95% CI using Poisson regression. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to estimate the HR with 95% CI of empyema associated with splenectomy and other comorbidities, after simultaneously adjusting for confounding variables in the univariable Cox proportional hazard regression model. The proportional hazard model assumption was examined using a test of scaled Schoenfeld residuals. The results of the model that evaluated the risk of empyema throughout the follow-up period revealed a significant association between Schoenfeld residuals for splenectomy and follow-up period, suggesting that the proportionality assumption was violated (p<0.001). In the subsequent analysis, we stratified the follow-up period to avoid violation of the proportional hazard assumption. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS V9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Two-tailed p values of<0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Baseline data of the study subjects

Table 1 shows the baseline data of the study subjects. A total of 13 193 subjects with splenectomy and 52 464 subjects without splenectomy were included, with similar distributions in sex and age. Mean ages (mean±SD) were 52.8±17.2 years in the splenectomy group and 52.5±17.2 years in the non-splenectomy group (t-test; p=0.05). Mean follow-up periods (mean±SD) were 4.37±3.44 person-years in the splenectomy group and 5.75±3.32 person-years in the non-splenectomy group (t-test; p<0.001). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of comorbidities between the splenectomy and non-splenectomy groups (χ2 test; p>0.05 for all).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics between splenectomy group and non-splenectomy group

| Variable | Splenectomy | p Value* | |||

| No n=52 464 |

Yes n=13 193 |

||||

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | 0.88 | ||||

| Female | 20 431 | 38.9 | 5128 | 38.9 | |

| Male | 32 033 | 61.1 | 8065 | 61.1 | |

| Age group (years) | 0.98 | ||||

| 20–39 | 13 415 | 25.6 | 3364 | 25.5 | |

| 40–64 | 24 112 | 46.0 | 6062 | 46.0 | |

| 65–84 | 14 937 | 28.5 | 3767 | 28.6 | |

| Age (years), mean (SD)† | 52.5 | (17.2) | 52.8 | (17.2) | 0.05 |

| Follow-up period (years), mean (SD)† | 5.75 | (3.32) | 4.37 | (3.44) | <0.001 |

| Baseline comorbidities | |||||

| Alcohol-related disease | 1787 | 3.41 | 452 | 3.43 | 0.91 |

| Cancer | 7677 | 14.6 | 1962 | 14.9 | 0.49 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1068 | 2.04 | 270 | 2.05 | 0.94 |

| Chronic liver disease | 7791 | 14.9 | 1971 | 14.9 | 0.80 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2002 | 3.82 | 507 | 3.84 | 0.89 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 7856 | 15.0 | 1983 | 15.0 | 0.87 |

Data are presented as the number of subjects in each group, with percentages given in parentheses, or mean with SD given in parentheses.

*χ2 test, and

†t-test comparing subjects with and without splenectomy.

Incidence of empyema stratified by sex, age and follow-up period

Table 2 shows the incidence rates of empyema. At the end of the cohort study, the overall incidence rate of empyema was 2.56-fold higher in the splenectomy group than in the non-splenectomy group (8.85 vs 3.46 per 1000 person-years; 95% CI 2.44 to 2.69). The incidence rate of empyema, stratified by sex, age and follow-up period, was higher in the splenectomy group than in the non-splenectomy group. The incidence rate of empyema increased with age in both the groups, with the highest rate reported in the splenectomy group with subjects aged 65–84 years (19.2 per 1000 person-years). Stratified analysis by follow-up period revealed that the incidence rate of empyema decreased with the follow-up period in both the groups. The risk of empyema in the splenectomy group was significantly higher in the first 5 years of follow-up (IRR, 2.87; 95% CI 2.73 to 3.01). However, risk of empyema continued to exist in the splenectomy group even after 5 years (IRR, 1.73; 95% CI 1.60 to 1.88).

Table 2.

Incidence density of empyema estimated by sex, age and follow-up period between splenectomy group and non-splenectomy group

| Variable | Non-splenectomy | Splenectomy | IRR† | (95% CI) | ||||||

| n | Cases | Person- years | Incidence* | n | Cases | Person- years | Incidence * | |||

| All | 52 464 | 1042 | 3 01 484 | 3.46 | 13 193 | 510 | 57 622 | 8.85 | 2.56 | (2.44 to 2.69) |

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 20 431 | 317 | 1 19 441 | 2.65 | 5128 | 159 | 23 004 | 6.91 | 2.60 | (2.40 to 2.82) |

| Male | 32 033 | 725 | 1 82 042 | 3.98 | 8065 | 351 | 34 618 | 10.1 | 2.55 | (2.39 to 2.71) |

| Age group (years) | ||||||||||

| 20–39 | 13 415 | 57 | 84 004 | 0.68 | 3364 | 65 | 19 700 | 3.30 | 4.86 | (4.39 to 5.39) |

| 40–64 | 24 112 | 354 | 1 40 554 | 2.52 | 6062 | 224 | 26 423 | 8.48 | 3.37 | (3.13 to 3.62) |

| 65–84 | 14 937 | 631 | 76 925 | 8.20 | 3767 | 221 | 11 499 | 19.2 | 2.34 | (2.14 to 2.56) |

| Follow-up period (years) | ||||||||||

| <5 | 52 464 | 720 | 2 06 010 | 3.49 | 13 193 | 416 | 41 545 | 10.0 | 2.87 | (2.73 to 3.01) |

| ≥5 | 28 456 | 322 | 95 474 | 3.37 | 5052 | 94 | 16 077 | 5.85 | 1.73 | (1.60 to 1.88) |

*Incidence rate: per 1000 person-years.

†IRR (incidence rate ratio): splenectomy versus non-splenectomy (95% CI).

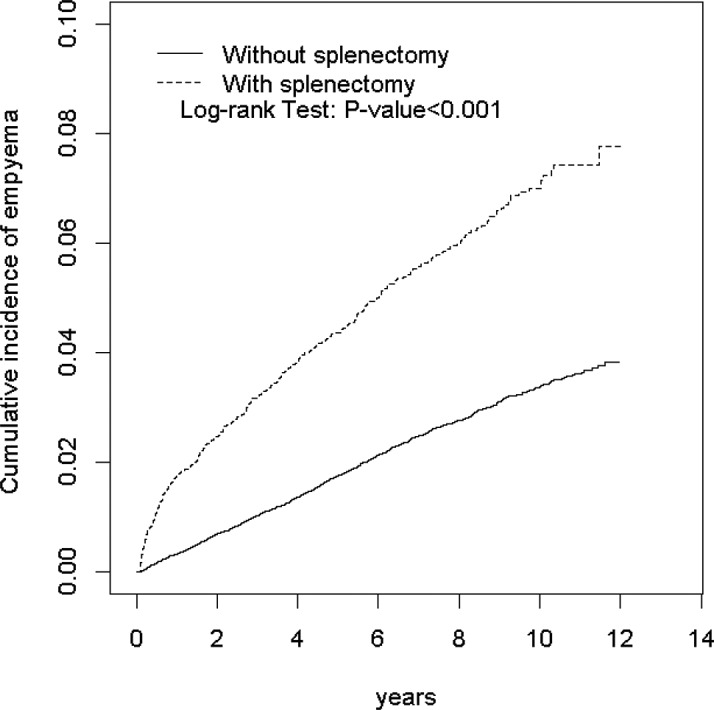

The Kaplan-Meier model revealed a higher cumulative incidence of pleural empyema in the splenectomy group than in the non-splenectomy group (6.99% vs 3.37% at the end of follow-up; p<0.001; figure 1).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier model revealed that the splenectomy group had a higher cumulative incidence of pleural empyema than the non-splenectomy group (6.99% vs 3.37% at the end of follow-up; p<0.001).

HR of empyema associated with splenectomy and other comorbidities

Table 3 displays HR of empyema associated with splenectomy and other comorbidities. Variables that were found to be statistically significant in the univariable model were further examined in the multivariable model. After adjusting for age, sex, alcohol-related disease, cancers, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diabetes mellitus, the multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression model revealed that the adjusted HR of empyema was 2.89 in the splenectomy group (95% CI 2.60 to 3.22) compared with that in the non-splenectomy group.

Table 3.

Adjusted HR and 95% CI of empyema associated with splenectomy and other comorbidities

| Variable | Crude | Adjusted* | ||

| HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | |

| Sex (male vs female) | 1.48 | (1.33 to 1.65) | 1.51 | (1.35 to 1.68) |

| Age (per 1 year) | 1.05 | (1.04 to 1.05) | 1.05 | (1.05 to 1.06) |

| Baseline comorbidities (yes vs no) | ||||

| Splenectomy | 2.52 | (2.26 to 2.80) | 2.89 | (2.60 to 3.22) |

| Alcohol-related disease | 1.61 | (1.28 to 2.03) | 2.25 | (1.76 to 2.86) |

| Cancer | 2.60 | (2.31 to 2.92) | 1.92 | (1.71 to 2.17) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3.04 | (2.40 to 3.85) | 2.13 | (1.67 to 2.70) |

| Chronic liver disease | 2.07 | (1.84 to 2.34) | 1.90 | (1.68 to 2.14) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3.95 | (3.37 to 4.64) | 1.75 | (1.48 to 2.07) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.80 | (2.51 to 3.13) | 1.85 | (1.65 to 2.07) |

Adjusted for age, sex, alcohol-related disease, cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diabetes mellitus.

*Variables found to be statistically significant in the univariable model were further examined in the multivariable model.

Interaction effect between splenectomy and other comorbidities on the risk of empyema

Table 4 displays the interaction effect between splenectomy and other comorbidities, including alcohol-related diseases, cancers, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases and diabetes mellitus, on the risk of empyema. The adjusted HR of empyema was 4.52 for subjects with splenectomy alone and without any comorbidity (95% CI 3.80 to 5.37). HR markedly increased to 8.23 for subjects with splenectomy and with any comorbidity (95% CI 6.98 to 9.70), demonstrating an interaction effect between splenectomy and other comorbidities on the risk of empyema.

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazard regression analysis for risk of empyema stratified by splenectomy and comorbidities

| Variable | Event | Incidence* | Adjusted HR† (95% CI) | |

| Splenectomy | Any comorbidity‡ | |||

| No | No | 299 | 1.49 | 1 (Reference) |

| No | Yes | 743 | 7.34 | 3.64 (3.18 to 4.17) |

| Yes | No | 230 | 5.75 | 4.52 (3.80 to 5.37) |

| Yes | Yes | 280 | 15.9 | 8.23 (6.98 to 9.70) |

*Incidence rate: per 1000 person-years.

†Adjusted for sex and age.

‡Comorbidities including alcohol-related disease, cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diabetes mellitus.

Discussion

Sinwar34 found that the duration between splenectomy and the onset of overwhelming postsplenectomy infections could range from <1 week to >20 years. To reduce biased results, patients who underwent splenectomy within 1 month of empyema diagnosis were excluded to ensure that splenectomy truly preceded the onset of empyema.

Extensive evidence has supported the protective role of the human spleen against invading microorganisms on the basis of the bactericidal capacity of lymphoid cells and macrophages, as well as humoral immune response.6 35–37 Following splenectomy, normal immune functions such as phagocytic activity and humoral immune response may be significantly changed. Therefore, impaired postsplenectomy immune functions may increase the risk of a life-threatening infection and empyema. In our study, the risk of empyema in the splenectomy group was higher in the first 5 years of follow-up than after the first 5 years (IRR, 2.87 vs 1.73). However, the risk of empyema continued to exist in the splenectomy group, even after the first 5 years. These findings are compatible with previously reported findings that revealed that the majority of severe infections occur within the first 3 years following splenectomy; although the risk declines over time, it may last for >5 years following splenectomy.38–40 However, the exact mechanism underlying this risk remains unknown. We speculate that with time, the immune system may develop compensatory mechanisms that may overcome these immune deficits. Future studies are required to confirm this hypothesis.

To the best of our knowledge, this population-based cohort study is the first to reveal that splenectomy is associated with an increased HR of empyema (adjusted HR, 2.89). Some studies have reported that splenectomy is associated with an increased risk of diseases. Lai et al compared between splenectomy patients and non-splenectomy patients and found that for postsplenectomy patients, the adjusted OR of acute pancreatitis was 2.90 (95% CI 1.39 to 6.05),12 the adjusted HR of renal and perinephric abscesses was 2.24 (95% CI 1.30 to 3.88),11 the adjusted HR of pyogenic liver abscess was 3.89 (95% CI 3.20 to 4.72)10 and the OR of pulmonary tuberculosis were 1.91 (95% CI 1.06 to 3.44).8

In this study, after adjusting for potential confounding variables, we also observed that the splenectomy group was at an increased risk of empyema (adjusted HR, 2.89). This phenomenon would typically be regarded as counterintuitive, but the exact reason remains unclear. A possible reason can be that some comorbidities that are potentially associated with empyema should have been included in the study; however, further studies are required to explain this phenomenon. The HR was higher than that observed for comorbidities. HR was not confounded by comorbidities because there was no significant difference in the prevalence of comorbidities between the splenectomy and non-splenectomy groups. This indicates that the increased HR of empyema in patients with splenectomy cannot be completely attributed to the prevalence of comorbidities. Although these comorbidities were found to be associated with empyema, to minimise their confounding effects, a further analysis was conducted. It was noted that in absence of any comorbidity, patients with splenectomy continued to have a higher HR of empyema (HR, 4.52). These results indicate that even in the absence of comorbidities, splenectomy may have a unique role in the risk of developing empyema. These findings are compatible with previously reported findings in the literature, in which patients with splenectomy are more prone to have severe life-threatening infections owing to an immunocompromised condition following splenectomy41 42 and are at an increased risk of developing empyema.

The limitations of this study as follows. First, some traditional behaviour risk factors, including alcohol consumption and cigarette smoking, were not considered owing to inherent limitations of the insurance database. We used alcohol-related diseases instead of alcohol consumption and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease instead of cigarette smoking. Second, the underlying causes for splenectomy were also not recorded owing to limitation of the database. Splenectomy is common in certain disorders and diseases such as haematological disorders, gastric cancer or trauma; thus, these background conditions may confound the results. We could not clarify the association of the cause of splenectomy with the development of empyema in this study. Third, owing to the limitation of the database, the underlying causes for splenectomy were not recorded. The cause of splenectomy could be the cause of empyema, for example, splenic abscess. Considering the high quality of the Taiwan medical system, 1 month is not required to confirm empyema diagnosis from the onset of empyema prodrome. To reduce biased results, subjects with an empyema diagnosis within 1 month following splenectomy were excluded. Therefore, it is less likely that splenectomy is the cause of empyema. Fourth, empyema could very well correlate with open surgery. However, owing to the previously mentioned limitations, the splenectomy type was not recorded. It is not known if splenectomy was performed via open or laparoscopic surgery or if it was a total or partial splenectomy. Fifth, the lack of vaccination could very well correlate with empyema. However, the number of subjects with splenectomy who were vaccinated against encapsulated bacteria (particularly Streptococcus pneumoniae) was unknown; thus, we could not investigate whether pneumococcal vaccination decreased the risk of empyema. Sixth, as causative pathogens were not recorded, the types of bacteria that contributed to empyema development could not be investigated. The lack of such data did not permit us to conclude a substantial causality. This case–control study included only patients with splenectomy, which may limit the generalisability of the study results to the general population. Such a study design does not permit to conclude a substantial causality. Further prospective studies are required to confirm the findings of our study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first original study to describe the association between splenectomy and empyema. Although the underlying mechanisms that associate splenectomy and empyema could not be completely determined, our findings are novel and clinically important. In addition, we used a hospitalisation dataset that had a large sample size and substantial statistical power. The diagnosis codes of the included comorbidities have been previously documented.23–33 The study design and statistical methodology are described in detail, and our results are relatively promising. Because the splenectomy and non-splenectomy groups had similar distributions of the studied comorbidities, the confounding effects of the comorbidities on the risk of empyema appear to be minimal.

The IRR between the splenectomy and non-splenectomy groups reduced from 2.87 in the first 5 years of follow-up to 1.73 in the period following the 5 years. Future studies are required to confirm whether a longer follow-up period would further reduce this average ratio. For the splenectomy group, the overall HR of developing empyema was 2.89 after adjusting for age, sex and comorbidities, which were identified from previous literature (including alcohol-related disease, cancer, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and diabetes mellitus). The risk of empyema following splenectomy remains high despite the absence of these comorbidities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Taiwan Ministry of Health and Welfare Clinical Trial Center (MOHW106-TDU-B-212-113004), China Medical University

Hospital, Academia Sinica Taiwan Biobank Stroke Biosignature Project (BM10601010036), Taiwan Clinical Trial Consortium for Stroke(MOST 106-2321-B-039-005), Tseng-Lien Lin Foundation, Taichung, Taiwan, Taiwan Brain Disease Foundation, Taipei, Taiwan and Katsuzo and Kiyo Aoshima Memorial Funds, Japan. These funding agencies did not influence the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: H-FL and K-FL planned and conducted this study, participated in the data interpretation and revised the article. They contributed equally to the article. C-MC and C-LL conducted the data analysis and revised the article. S-WL planned and conducted this study, contributed to the conception of the article, initiated the draft of the article and revised the article.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Patient/guardian consent obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of China Medical University and Hospital in Taiwan (CMUH-104-REC 2-115).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data available.

References

- 1. Ahmed RA, Marrie TJ, Huang JQ. Thoracic empyema in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med 2006;119:877–83. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.03.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shields T, Locicero J, Ponn R, et al. General thoracic surgery. 6th edn Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005:823. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Septimus EJ. Pleural effusion and empyema : Mandell GL, Bennet JE, Mandell RD, Douglas and bennett’s principles and practice of infectious diseases. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2009:917–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Spencer RP, Pearson HA. The spleen as a hematological organ. Semin Nucl Med 1975;5:95–102. 10.1016/S0001-2998(75)80007-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Trigg ME. Immune function of the spleen. South Med J 1979;72:593–9. 10.1097/00007611-197905000-00025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jirillo E, Mastronardi ML, Altamura M, et al. . The immunocompromised host: immune alterations in splenectomized patients and clinical implications. Curr Pharm Des 2003;9:1918–23. 10.2174/1381612033454306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Di Sabatino A, Carsetti R, Corazza GR. Post-splenectomy and hyposplenic states. Lancet 2011;378:86–97. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61493-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lai SW, Wang IK, Lin CL, et al. . Splenectomy correlates with increased risk of pulmonary tuberculosis: a case-control study in Taiwan. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014;20:764–7. 10.1111/1469-0691.12516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wu SC, Fu CY, Muo CH, et al. . Splenectomy in trauma patients is associated with an increased risk of postoperative type II diabetes: a nationwide population-based study. Am J Surg 2014;208:811–6. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2014.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lai SW, Lai HC, Lin CL, et al. . Splenectomy correlates with increased risk of pyogenic liver abscess: a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. J Epidemiol 2015;25:561–6. 10.2188/jea.JE20140267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lai SW, Lin HF, Lin CL, et al. . Splenectomy and risk of renal and perinephric abscesses: A population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Medicine 2016;95:e4438. 10.1097/MD.0000000000004438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lai SW, Lin CL, Liao KF. Splenectomy Correlates With Increased Risk of Acute Pancreatitis: A Case-Control Study in Taiwan. J Epidemiol 2016;26:488–92. 10.2188/jea.JE20150214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Liu WH, Liu TC, Mong MC. Antibacterial effects and action modes of asiatic acid. Biomedicine-Taiwan 2015;5:22–9. 10.7603/s40681-015-0016-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lin CJ, Lai CK, Kao MC, et al. . Impact of cholesterol on disease progression. Biomedicine-Taiwan 2015;5:1–7. 10.7603/s40681-015-0007-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lin CH, Li TC, Tsai PP, et al. . The relationships of the pulmonary arteries to lung lesions aid in differential diagnosis using computed tomography. Biomedicine-Taiwan 2015;5:31–8. 10.7603/s40681-015-0011-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tc L, Ci L, Liao LN, et al. . Associations of EDNRA and EDN1 polymorphisms with carotid intima media thickness through interactions with gender, regular exercise, and obesity in subjects in Taiwan: Taichung community health study (TCHS). Biomedicine-Taiwan 2015;5:8–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chen HX, Lai CH, Hsu HY, et al. . The bacterial interactions in the nasopharynx of children receiving adenoidectomy. Biomedicine-Taiwan 2015;5:39–43. 10.7603/s40681-015-0006-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National health insurance research database. Taiwan: http://nhird.nhri.org.tw/en/index.html (cited 1 Mar 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lai SW, Liao KF, Liao CC, et al. . Polypharmacy correlates with increased risk for hip fracture in the elderly: a population-based study. Medicine 2010;89:295–9. 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181f15efc [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen HY, Lai SW, Muo CH, et al. . Ethambutol-induced optic neuropathy: a nationwide population-based study from Taiwan. Br J Ophthalmol 2012;96:1368–71. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2012-301870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yang SP, Muo CH, Wang IK, et al. . Risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in female breast cancer patients treated with morphine: A retrospective population-based time-dependent cohort study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2015;110:285–90. 10.1016/j.diabres.2015.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tsai TY, Lin CC, Peng CY, et al. . The association between biliary tract inflammation and risk of digestive system cancers: A population-based cohort study. Medicine 2016;95:e4427 10.1097/MD.0000000000004427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lai SW, Chen PC, Liao KF, et al. . Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in diabetic patients and risk reduction associated with anti-diabetic therapy: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:46–52. 10.1038/ajg.2011.384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liao KF, Lin CL, Lai SW, et al. . Zolpidem use associated with increased risk of pyogenic liver abscess: a case-control study in Taiwan. Medicine 2015;94:e1302 10.1097/MD.0000000000001302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wong TS, Liao KF, Lin CM, et al. . Chronic Pancreatitis Correlates With Increased Risk of Cerebrovascular Disease: A Retrospective Population-Based Cohort Study in Taiwan. Medicine 2016;95:e3266 10.1097/MD.0000000000003266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Liao KF, Lai SW, Lin CL, et al. . Appendectomy correlates with increased risk of pyogenic liver abscess: A population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Medicine 2016;95:e4015 10.1097/MD.0000000000004015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cheng KC, Lin WY, Liu CS, et al. . Association of different types of liver disease with demographic and clinical factors. Biomedicine-Taiwan 2016;6:16–22. 10.7603/s40681-016-0016-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liao KF, Cheng KC, Lin CL, et al. . Etodolac and the risk of acute pancreatitis. Biomedicine-Taiwan 2017;7:4–9. 10.1051/bmdcn/2017070104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Shen ML, Liao KF, Tsai SM, et al. . Herpes zoster correlates with pyogenic liver abscesses in Taiwan. Biomedicine-Taiwan 2016;6:24–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lai SW. Risks and benefits of zolpidem use in Taiwan: a narrative review. Biomedicine-Taiwan 2016;6:9–11. 10.7603/s40681-016-0008-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cheng KC, Lee TL, Lin YJ, et al. . Facility evaluation of resigned hospital physicians:managerial implications for hospital physician manpower. Biomedicine-Taiwan 2016;6:30–9. 10.7603/s40681-016-0023-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lai SW, Lin CL, Liao KF. Risk of contracting pneumonia among patients with predialysis chronic kidney disease: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Biomedicine-Taiwan 2017;7:20–47. 10.1051/bmdcn/2017070320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liao KF, Huang PT, Lin CC, et al. . Fluvastatin use and risk of acute pancreatitis: a population-based case-control study in Taiwan. Biomedicine-Taiwan 2017;7:24–8. 10.1051/bmdcn/2017070317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sinwar PD. Overwhelming post splenectomy infection syndrome - review study. Int J Surg 2014;12:1314–6. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eibl M. Immunological consequences of splenectomy. Prog Pediatr Surg 1985;18:139–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Van Rooijen N. The humoral immune response in the spleen. Res Immunol 1991;142:328–30. 10.1016/0923-2494(91)90084-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Altamura M, Caradonna L, Amati L, et al. . Splenectomy and sepsis: the role of the spleen in the immune-mediated bacterial clearance. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol 2001;23:153–61. 10.1081/IPH-100103856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bisharat N, Omari H, Lavi I, et al. . Risk of infection and death among post-splenectomy patients. J Infect 2001;43:182–6. 10.1053/jinf.2001.0904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kyaw MH, Holmes EM, Toolis F, et al. . Evaluation of severe infection and survival after splenectomy. Am J Med 2006;119:276 e1–7. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.07.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dendle C, Sundararajan V, Spelman T, et al. . Splenectomy sequelae: an analysis of infectious outcomes among adults in Victoria. Med J Aust 2012;196:582–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Di Cataldo A, Puleo S, Li Destri G, et al. . Splenic trauma and overwhelming postsplenectomy infection. Br J Surg 1987;74:343–5. 10.1002/bjs.1800740504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lynch AM, Kapila R. Overwhelming postsplenectomy infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1996;10:693–707. 10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70322-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.