Abstract

Introduction

A protective HIV vaccine would be expected to induce durable effector immune responses at the mucosa, restricting HIV infection at its portal of entry. We hypothesise that use of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) as an HIV delivery vector could generate sustained and robust tissue-based immunity against HIV antigens to provide long-term protection against HIV. Given that HIV uniquely targets immune-activated T cells, the development of human vaccines against HIV must also involve a specific examination of the safety of the vector. Thus, we aim to evaluate the effects of VZV vaccination on the recipients’ immune activation state, and on VZV-specific circulating humoral and cellular responses in addition to those at the cervical and rectal mucosa.

Methods and analysis

This open-label, randomised, longitudinal crossover study includes healthy Kenyan VZV-seropositive women at low risk for HIV infection. Participants receive a single dose of a commercial live-attenuated VZVOka vaccine at either week 0 (n=22) or at week 12 (n=22) of the study and are followed for 48 and 36 weeks postvaccination, respectively. The primary outcome is the change on cervical CD4+ T-cell immune activation measured by the coexpression of CD38 and HLA-DR 12 weeks postvaccination compared with the baseline (prevaccination). Secondary analyses include postvaccination changes in VZV-specific mucosal and systemic humoral and cellular immune responses, changes in cytokine and chemokine measures, study acceptability and feasibility of mucosal sampling and a longitudinal assessment of the bacterial community composition of the mucosa.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has ethical approval from Kenyatta National Hospital/University of Nairobi Ethics and Research Committee, the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board and by Kenyan Pharmacy and Poisons Board. Results will be presented at conferences, disseminated to participants and stakeholders as well as published in peer-reviewed journals.

Trial registration number

NCT02514018. Pre-results.

Keywords: varicella-zoster virus, HIV vaccine, immune activation, mucosal immunity, herpes zoster, herpesviridae infections, virus diseases

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first human study to determine whether there is any evidence for systemic or local immune activation induced by a live-attenuated varicella-zoster virus (VZV)Oka vaccine and to characterise VZV-specific mucosal immune responses at sites important for HIV transmission.

It will provide safety evidence to further explore the potential of VZV as a vector for an HIV vaccine.

This study will generate normative immune activation values across multiple sites (cervix, rectum, blood) serving as a guide when planning clinical trials.

Potential limitations include relatively small sample size, uncertainty of the relationship of changes in mucosal activation and HIV transmission risk, confounders of mucosal activation (like bacterial vaginosis), inclusion of women only and the lack of a definitive marker of HIV risk.

Introduction

An effective HIV-1 vaccine remains an urgent global priority. As sexual transmission is the most common mode of acquisition, the induction of HIV-specific effector immune responses able to curtail viral infection and dissemination at the mucosal or tissue level is widely seen as the logical first line of defence and a critical component for any preventive vaccine strategy against HIV.1–3 The use of latent viral vectors, such as varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV), has significant potential to generate these types of responses. This is in contrast to most of the vaccine vectors currently in study, such as adenovirus (Ad), which induce only a central memory T-cell phenotype, a type of immune response that is centred in the lymph nodes and that requires time to migrate to the infection site.

CMV has been successfully tested in rhesus macaques as a recombinant replicating vector for Simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) antigens. Results showed apparent complete control of SIV viraemia in 50% of the animals vaccinated with RhCMV-SIV and challenged with a highly virulent SIV strain (SIVmac239).2 4 Similar to CMV, VZV is a strong candidate to carry HIV genes, with the advantage of being the only persistent replicating virus currently approved as a vaccine in humans.

VZV is a double-stranded DNA virus, member of alphaherpesvirus subfamily. Primary infection with VZV, also known as varicella or chickenpox, is clinically characterised by fever, malaise and rash. The diffuse vesicular skin lesions predominantly crust and dry within several days coincident with the resolution of viral shedding. Following the resolution of primary infection with VZV, the virus establishes latent infection in the cranial nerve ganglia and dorsal root ganglia including those of the viscera and gut.5–7 Throughout a person’s life, VZV-specific immune responses are boosted either by subclinical viral reactivation and/or exogenous re-exposures to the virus preventing clinically apparent reactivation or secondary infection, known as herpes zoster or shingles.8–10 Live-attenuated varicella vaccines have been used worldwide to prevent varicella and zoster infections and have a well-described safety and protective profiles.11–16

VZV carries several features that make it a promising vector for foreign antigens in recombinant vaccines.17 VZV is a non-retroviral, non-integrating virus, capable of large exogenous DNA insertions, cloned as a bacterial artificial chromosome, amenable to genetic manipulation and able to induce long-lived humoral and cellular responses, including polyfunctional central and effector memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood.9 16–20 We hypothesise that a low level of antigen exposure during VZV subclinical reactivation, including viral gene expression during latency,21 may allow lifelong boosting of immune responses when used as a vector in conjunction with HIV, generating durable immunity systemically. Besides, recent findings showing that VZV can alter cell signalling to augment T-cell skin trafficking22 coupled with its ability to establish latency in enteric neurons and to undergo reactivation in the gut7 23 call for further investigation of the presence of VZV-specific cells at the mucosa. Favouring the maintenance of a pool of effector memory T cells at the mucosa able to act at the early stages of infection could prevent HIV spread or change the course of disease progression.

The STEP and HVTN505 trials, which used adenovirus 5 (Ad5) as a recombinant vector for HIV-1 genes however, raised concerns about the safety of any viral vector because of enhanced risk of acquisition of HIV-1 in a subgroup with pre-existing Ad5 immunity.24 25 Although the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon are not fully understood, it is prudent to carefully assess the mucosal immunity induced by any vector itself before its use as an HIV antigen carrier in an efficacy trial.

Activated CD4+ T cells are more susceptible to HIV infection and an increase on their mucosal availability can put individuals at a higher risk of HIV acquisition as shown by studies in HIV-exposed seronegative individuals, non-human primate models and in vitro assays.26–31

In this study, we aim to characterise mucosal immunity before and after vaccination with a commercial live-attenuated VZV vaccine with respect to immune activation state, mucosal homing properties and VZV-specific effector immune responses in Kenyan women at low risk for HIV acquisition and with preimmunity to VZV through natural infection. Characterising VZV responses in this study setting is highly relevant, since Kenya, along with other African countries, is among the countries which can derive the greatest benefit with an HIV vaccine. In addition to helping set the groundwork for a future HIV vaccine, this study will also generate data on VZV seroprevalence and immunogenicity of the vaccine in an African cohort, which will guide other studies and health programme directed against VZV infections.

Methods and analysis

Study design

KAVI-VZV-001 is an open-label, randomised, controlled, longitudinal crossover study of VZV vaccine. This study will enrol 44 healthy female participants who will be randomised 1:1 into the immediate versus delayed groups (vaccinated at week 0 or at week 12, respectively) and followed prospectively after enrolment for 48 weeks. The study is being conducted at the Kenyan AIDS Vaccine Initiative-Institute of Clinical Research (KAVI-ICR) in Nairobi, Kenya. This study is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02514018. KAVI-VZV-001 started in October 2015 and sample collections will be completed before December 2017.

Study population

KAVI-ICR Community mobilisers work with a dedicated group of peer leaders and peer educators to reach out to members of the general public. Healthy women in Nairobi, Kenya, aged 18–50 years, not pregnant or breast feeding, with preimmunity to VZV (determined by the presence of VZV-specific IgG in their plasma) are eligible. Eligibility to participate in the study depends on results of screening laboratory investigations, review of medical history, physical examination, answers to questions about HIV risk behaviours and willingness to use an effective contraceptive method during the period of the study. The detailed list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is shown in box 1.

Box 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for KAVI-VZV-001 trial.

Inclusion criteria

female, with no chronic medical condition as assessed by a medical history, physical examination and laboratory tests;

at least 18 years of age on the day of screening and has not reached her 51st birthday on the day of first vaccination;

varicella-zoster virus seropositive, as assessed by the Vitek Immuno Diagnostic Assay System (VIDAS) assay;

willing to comply with the requirements of the protocol and available for follow-up for the planned duration of the study;

In the opinion of the principal investigator or designee, and based on assessment of informed consent understanding results, has understood the information provided and potential impact and/or risks linked to vaccination and participation in the trial;

Willing to undergo HIV testing, risk reduction counselling and receive HIV test results;

For women with potential to become pregnant, willing to use effective contraception or barrier methods to avoid pregnancy during the study (spermicides or chemicals are not allowed).

Exclusion criteria

-

A high risk for HIV acquisition defined by the experience of any of the following situations:

had unprotected vaginal or anal sex with a known HIV-1-infected person, a person known to be at high risk for HIV or a casual partner (ie, no continuing, established relationship) within the previous 6 months;

engaged in sex work for money or drugs within the previous 6 months;

used injection drugs within the previous 6 months;

abuse of illicit or prescribed drugs, including alcohol, within the previous 6 months;

acquired one of the following sexually transmitted infections in the last 12 months: chlamydia, gonorrhoea or syphilis;

more than one sexual partner within the last 6 months;

new sexual partner within the last 3 months.

persistent or recurrent bacterial vaginosis or vaginal candidiasis unresponsive to therapy (two consecutive attempts by study team);

confirmed HIV-1 or HIV-2 infection;

any clinically significant acute or chronic medical condition that is considered progressive or, in the opinion of the principal investigator or designee, would make the volunteer unsuitable for the study (active or underlying diabetes, gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, malignancy, neurological, psychiatric, metabolic, renal, hepatic, respiratory, autoimmune diseases, psoriasis, primary and acquired immunodeficiency status and rectal problems);

-

any of the following abnormal laboratory parameters except that one abnormal laboratory test may be repeated once if thought to be due to a temporary condition:

-

Haematology

haemoglobin <9.0 g/dL;

platelets ≤100 000/mm3, ≥550 000/mm3 (≤100/L, ≥550/L).

-

Coagulation

international normalised ratio <1.0 or >1.5

-

evidence of coagulopathy demonstrated by a reduced level of platelets or a history of three or more episodes of uncontrolled bleeding from their mouth, nose or other mucous membrane (marked by excessive bleeding of >30 min);

a positive pregnancy test or breast feeding at screening; for the participants with reproductive potential, unwilling to use an effective method of preventing pregnancy during the study;

receipt of vaccine within the previous 2 months or planned receipt at any time until 6 months after vaccination with Zostavax;

receipt of blood transfusion or blood products within the previous 6 months;

participation in another clinical trial currently or within the previous 3 months;

history of severe or very severe local or systemic reactogenicity events after vaccination, or history of severe or very severe allergic reactions;

history of toxic shock syndrome;

confirmed diagnosis of acute or chronic hepatitis B virus infection (spontaneous clearance leading to natural immunity, indicated by antibodies to core+antigens, is not an exclusion criterion); confirmed diagnosis of hepatitis C virus infection;

immunosuppressive medications 30 days before or during the study period;

history of anaphylactic/anaphylactoid reaction to neomycin (each dose of reconstituted vaccine contains trace quantities of neomycin);

major psychiatric illness including any history of schizophrenia or severe psychosis, bipolar disorder, suicidal attempt or ideation in the previous 3 years;

contraindication for undergoing a biopsy due to bleeding diathesis, haemorrhoids, mucosal infection at the biopsy site, medication that interferes with clotting (eg, warfarin or heparin)—both clinical and laboratory;

any other reason as determined by the principal investigator.

Study agent and randomisation

Participants will receive a single dose of the commercial live-attenuated VZVOka (Zostavax, Merck) (≥19 400 plaque-forming units). The vaccine is stored and administered as per manufacturer’s instructions.

Participants are randomly assigned (1:1) into two groups, ‘immediate’ and ‘delayed’, according to a randomisation list prepared using Stat Trek’s Random Number Generator and stored locked by the clinic manager for the study. Participants and clinic personnel are not blinded with respect to group allocation. Laboratory personnel and data analysts are not informed about participants’ allocation while performing the analysis.

Study duration and procedures

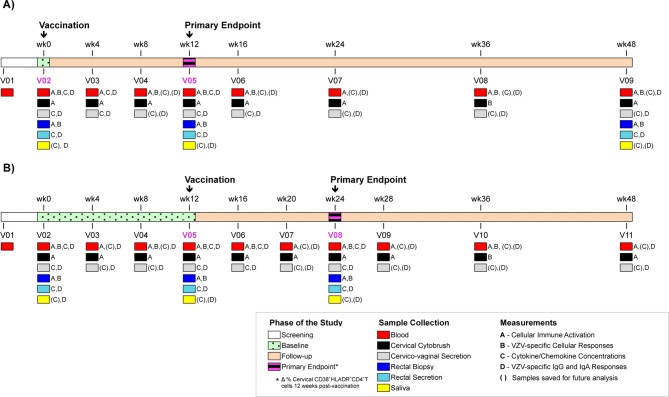

Participants are expected to attend 9–11 visits throughout the study depending on what group they have been assigned to. Figure 1 shows the timeline for both groups.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of enrolment and follow-up for KAVI-VZV-001 trial. (A) Immediate group and (B) delayed group. Immediate group receive a single dose of VZVOka vaccine at week 0 and delayed group at week 12. Participants are followed-up for a period of 36–48 weeks after receiving the vaccine. VZV, varicella-zoster virus.

At screening visit (V01), participants are asked to answer to a general questionnaire including questions about their demographics, HIV-risk exposure, willingness to use an effective contraceptive method and motivation to take part in the study. The study personnel review participants’ medical history and collect blood, urine and vaginal swabs to determine participant’s eligibility. The screening assays are described in the online supplementary table 1S. At each visit after enrolment, a symptom-directed physical examination is performed, concomitant medications are documented and sample collection or vaccination performed as summarised in figure 1. A detailed description of collection and management of samples (blood, cervicovaginal specimens, rectal specimens and saliva) as well as laboratory assessments is described in online supplementary material. Participants are instructed to report any adverse event over the course of the study during their scheduled visits or by scheduling a new appointment with the clinic staff. They are also instructed to use the memory aid to register any adverse event during the 14-day period that follows vaccination. Participants receive counselling about HIV risk and contraceptive use and are tested for bacterial vaginosis and vaginal candidiasis every visit. HIV testing is performed three times in the study and whenever the clinic staff thinks it is recommended.

bmjopen-2017-017391supp001.pdf (139.4KB, pdf)

Visits are rescheduled if women are menstruating or spotting. The final scheduled visit occurs at 48 weeks postenrolment in the study. Volunteers can terminate their attendance early as can the study investigator if it is judged to be in the best interest of the individual. Participants are declared lost after three or more missed visits without rescheduling. Any subject seroconverting to HIV would be withdrawn from the study, counselled and offered care.

Data collection and record-keeping

A participant’s file, including all case report forms, laboratory results and so on, is maintained in a secure location at the trial site and retained as required by the International Conference on Harmonisation-Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) Guidelines and applicable local requirements. The participant’s personal information (name, contacts and address) together with signed informed consent form is stored in a secure location separate from the participant’s file. An electronic database (designed with the OpenClinica Software) is used to keep all the data collected for the participants. Access to the database is restricted by login and password, and the database is maintained and secured by KAVI-ICR Information Technology department. Participants are identified in the database using only their trial number.

Study outcomes

The primary objective is to assess whether VZV vaccination induces a sustained elevated frequency of activated CD4+ T cells measured as a percentage of CD4+ T cells coexpressing HLA-DR and CD38 at the cervical mucosa. CD38+HLA-DR+CD4+ T cells have shown to be highly susceptible to HIV-1 infection.32 Hence, our primary end point is the change (∆) in frequency of cervical CD4+ T cells coexpressing CD38 and HLA-DR 12 weeks postvaccination compared with the baseline (prevaccination). The control condition is the change observed during the same period (12 weeks) in the group that has not been vaccinated (delayed group). Employing a delayed arm is important since individuals in any population are subject to fluctuations in their immune activation status in response to many factors, such as infections and stress.

We will also measure VZV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses in blood and rectum, as well as VZV-specific IgG and IgA responses in saliva, plasma, cervicovaginal secretion and rectal secretion longitudinally throughout 48 weeks. The primary and secondary outcomes are described in table 1 and all the prespecified outcomes for this study are described in the online supplementary table 2S.

Table 1.

Primary and secondary outcomes for KAVI-VZV-001 trial

| Outcome | Hypothesis | Outcome measure |

| Primary | ||

| Cervical mucosal immune activation after VZV vaccination | Vaccination against varicella does not result in elevated immune activation after 12 weeks of immunisation. | Change in frequency of cervical CD38+HLA-DR+CD4+ T cells 12 weeks after VZV vaccination compared with baseline |

| Secondary | ||

| (a) Effector VZV-specific CD8+ T cells at the rectal mucosa after VZV vaccination | Vaccination against varicella boosts effector VZV-specific CD8+ T-cell response at rectal mucosa. | Change in frequency of rectal VZV-specific IFN-γ-producing CD8+ TEM cells 12 weeks after VZV vaccination compared with baseline. |

| (b) Proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine secretion after VZV vaccination | Vaccination against varicella does not result in elevated proinflammatory signature after 12 weeks of immunisation. | Change in level of proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines in blood, cervix and rectum measured at 12 weeks after VZV vaccination compared with baseline |

IFN-γ, interferon gamma; VZV, varicella-zoster virus.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of the differences at baseline in the characteristics of women enrolled in each group will be assessed using Fisher’s exact test and t-test or Kruskal-Wallis test. In this delayed-start trial, there are two analysis periods: a placebo-controlled period followed by a delayed-start period that begins after all patients had received the vaccine. To assess the primary hypothesis (that the proportion of cervical HLA-DR+CD38+CD4+ T cells out of all CD4+ T cells 12 weeks after vaccination will not increase by >20%), we will estimate the difference in the mean change (∆) in the per cent HLA-DR+CD38+CD4+ T cells at 12 weeks (during the placebo-controlled period) between the immediate and delayed start groups. For each participant,

∆=per cent HLA-DR+CD38+CD4+ T cells at randomisation (week 0)−per cent HLA-DR+CD38+CD4+ T cells at week 12 postvaccination.

The primary hypothesis will be considered refuted if the upper 95% confidence limit of the mean ∆ exceeds 20%.

A similar approach will be used to assess differences among the delayed-start group, except that ∆ in this analysis will be calculated as:

∆=per cent HLA-DR+CD38+CD4+ T cells at 12 weeks following randomisation−per cent HLA-DR+CD38+CD4+ T cells at week 12 following delayed vaccination.

This analysis has the advantage of being adjusted for all potential fixed (non-time varying) confounders as each participant is acting as her own control.

In a third analysis, we will use a similar approach to measure differences between the two groups at the end of follow-up (48 weeks). This analysis will provide a test of the persistence of any differences observed at 12 weeks.

Sample size justification

Based on longitudinal changes on frequency of cervical HLA-DR+CD38+CD4+ T cells in a non-treatment arm (Tae Joon Yi, personal communication), a significant clinical outcome is considered to increase by ≥20% of cervical HLA-DR+CD38+CD4+ T cells after 12 weeks of vaccination when compared with their respective baseline after accounting for the changes observed for the same period in 12 weeks that preceded vaccination in the delayed group. Using a level of significance of 0.05, a power of 80% for this study and expecting 10% loss to follow-up during the trial, we established a sample size of 44.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical considerations

The study protocols, informed consent form and all required documentation were approved by KNH/UON ERC (reference number KNH-ERC/A/352), University of Toronto REB (protocol number 31043) and by Kenyan Pharmacy and Poisons Board (reference number PPB/ECCT/15/01/02/2015). Written informed consent was obtained for all participants prior to screening. This study is conducted and the data generated recorded and reported in accordance with the ICH Guidelines for GCP, regulatory requirements and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Dissemination

Study results will be presented at conferences, disseminated to participants and stakeholders, as well as published in peer-reviewed journals after thorough review by the investigators for its appropriateness and scientific relevance. No information that compromises participant’s confidentiality will be disseminated.

Discussion

After almost three decades of setbacks and failures, the findings of the RV144 trial (combination of AIDSVAX B/E gp120 and ALVAC Canarypox vaccines) injected a dose of optimism in the HIV vaccine field. The RV144 trial showed a modest protection (31.2%) against HIV acquisition.33 34 However, the rapidly waning efficacy observed in RV144 spurred on the testing of a number of heterologous prime-boost combinations in an effort to induce a durable and multifaceted immune response marked by the presence of both broadly neutralising antibodies and strong T-cell responses.35–37

As an alternative to the complex prime-boost strategies, the use of persistent replication-competent viral vectors offers the potential of long-lived protection. The ability of VZV to establish latency and develop long-lived humoral and cellular responses makes it an excellent backbone for HIV antigens delivered in a hybrid vaccine, potentially overcoming some of the main hurdles faced in the field. At the same time, VZV’s long-standing use as a safe and licensed live-attenuated vaccine in humans could accelerate a VZV-based HIV vaccine into human trials, preventing both a childhood disease and HIV, and thus reducing the stigma of HIV vaccination.

Greater than 90% of the adult population worldwide has been exposed to VZV via vaccination or natural infection and carry the dormant virus in their body. In the STEP and HVTN505 trials, individuals with preimmunity to the viral vector (Ad5) were at higher risk of HIV acquisition.24 25 These and other HIV vaccine trials have compared risk and protection of the vaccine candidates against placebo constituted of the vaccine diluent without the vector. We believe that by characterising the type and duration of mucosal immune responses, including immune activation, induced by the empty vector in a population at low risk for HIV infection, we will be able to screen for safer and better vector candidates.

HIV-1 infection is typically established via the mucosal route; hence, it is imperative that we study this site in detail in order to develop an HIV vaccine. The decision to recruit only women in our study was taken with this point in consideration. In order to perform the immunological measurements proposed here, we need to isolate T lymphocytes from the mucosa at multiple time points. As the magnitude and the kinetics of mucosal immune responses induced by VZV vaccination are very important, a longitudinal analysis is required. In this context, the collection of cervical mucosal cells using cervical cytobrushes appears the most suitable sample choice for several reasons: (1) it is a widely used and well-established method; (2) it is considered minimally invasive; (3) it is well accepted by women making its adoption in multiple time points possible and (4) cervical cells are relevant in the context of HIV acquisition and transmission. On the contrary, methods to measure immune responses in the male urethra are not well established; there are insufficient lymphocytes in semen to measure cellular immune responses; and cells isolated from semen are related only to HIV transmission, not acquisition. Alternatively, cells isolated from rectal biopsies can also be used to characterise the mucosal responses, with the advantage of providing a higher number of cells and allowing for the inclusion of both male and female individuals. However, as the acceptability of multiple rectal biopsy collections has not been determined in this population and can pose a challenge to longitudinal investigations (composed of 8–10 time points), we decided to recruit women only so as to implement both cervical and rectal cell collections, with the latter in a lower frequency than the former (3 vs 8–10 time points throughout the study). Importantly, this design allows for the comparison of the immune responses obtained between these two sites while providing data that can be applicable to the male population as well.

The inclusion of a delayed group, whose individuals are sampled four times before vaccination, allows for the characterisation and normalisation of fluctuations in immune activation markers such as CD69 and HLA-DR, VZV-specific responses due to viral subclinical reactivation. Our data will help establish a comprehensive assessment of the steady-state mucosal immune activation status prior to and following VZV vaccination within the understudied population of Kenyan women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr Rupert Kaul and Dr David Willer for their scientific advice, and Shariq Mujib for his revision of this manuscript. The authors also thank the following Kenyan AIDS Vaccine Initiative-Institute of Clinical Research members: Dr Gloria Omosa, Dr Mutua Gaudensia, Moses Muriuki and Jacquelyn Nyange and, at the University of Toronto, Jacqueline Chan, Fatima Csordas and Dr Joseph Antony for laboratory and organisational support.

Footnotes

Contributors: KSM conceived the study. CTP, KSM, WJ, OA, BF, SW and MO initiated, designed and implemented the study. Members of the Kenyan AIDS Vaccine Initiative-Institute of Clinical Research were involved with the design and study implementation. SMM is responsible for the primary statistical analysis. All authors contributed to refinement of the study and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study has been funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR Team Grant—Research Operating THA:11960). CTP was supported by Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship, The Delta Kappa Gamma Society World Fellowship and Ontario Graduate Scholarship. KSM was funded by an Ontario HIV Treatment Network Senior Investigator Award. KSM is currently supported by the HE Sellers Research Chair. SW is supported by a chair in clinical HIV management from the Ontario HIV treatment network. SMM is a Canada Research Chair in Pharmaco-epidemiology and Vaccine Evaluation.

Competing interests: SMM has received grants for unrelated studies from GSK, Merck, Pfizer and Sanofi, and served on advisory boards for GSK and Pfizer.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Kenyatta National Hospital/University of Nairobi Ethics and Research Committee, the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board and by Kenyan Pharmacy and Poisons Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. McMichael AJ, Borrow P, Tomaras GD, et al. . The immune response during acute HIV-1 infection: clues for vaccine development. Nat Rev Immunol 2010;10:11–23. 10.1038/nri2674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hansen SG, Ford JC, Lewis MS, et al. . Profound early control of highly pathogenic SIV by an effector memory T-cell vaccine. Nature 2011;473:523–7. 10.1038/nature10003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Picker LJ, Hansen SG, Lifson JD. New paradigms for HIV/AIDS vaccine development. Annu Rev Med 2012;63:95–111. 10.1146/annurev-med-042010-085643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hansen SG, Piatak M, Ventura AB, et al. . Immune clearance of highly pathogenic SIV infection. Nature 2013;502:100–4. 10.1038/nature12519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arvin AM. Varicella-zoster virus. Clin Microbiol Rev 1996;9:361–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heininger U, Seward JF. Varicella. Lancet 2006;368:1365–76. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69561-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen JJ, Gershon AA, Li Z, et al. . Varicella zoster virus (VZV) infects and establishes latency in enteric neurons. J Neurovirol 2011;17:578–89. 10.1007/s13365-011-0070-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krause PR, Klinman DM. Varicella vaccination: evidence for frequent reactivation of the vaccine strain in healthy children. Nat Med 2000;6:451–4. 10.1038/74715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Weinberg A, Levin MJ. VZV T cell-mediated immunity. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2010;342:341–57. 10.1007/82_2010_31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schünemann S, Mainka C, Wolff MH. Subclinical reactivation of varicella-zoster virus in immunocompromised and immunocompetent individuals. Intervirology 1998;41(2-3):98–102. 10.1159/000024920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gershon AA, Katz SL. Perspective on live varicella vaccine. J Infect Dis 2008;197(Suppl 2):S242–5. 10.1086/522151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gershon AA, Gershon MD. Perspectives on vaccines against varicella-zoster virus infections. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2010;342:359–72. 10.1007/82_2010_12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Takahashi M, Asano Y, Kamiya H, et al. . Development of varicella vaccine. J Infect Dis 2008;197(Suppl 2):S41–4. 10.1086/522132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, et al. . A vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2271–84. 10.1056/NEJMoa051016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Simberkoff MS, Arbeit RD, Johnson GR, et al. . Safety of herpes zoster vaccine in the shingles prevention study: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:545–54. 10.7326/0003-4819-152-9-201005040-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Levin MJ, Oxman MN, Zhang JH, et al. . Varicella-zoster virus-specific immune responses in elderly recipients of a herpes zoster vaccine. J Infect Dis 2008;197:825–35. 10.1086/528696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gray WL. Recombinant varicella-zoster virus vaccines as platforms for expression of foreign antigens. Adv Virol 2013;2013:1–8. 10.1155/2013/219439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schub D, Janssen E, Leyking S, et al. . Altered phenotype and functionality of varicella zoster virus-specific cellular immunity in individuals with active infection. J Infect Dis 2015;211:600–12. 10.1093/infdis/jiu500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sei JJ, Cox KS, Dubey SA, et al. . Effector and central memory poly-functional CD4(+) and CD8(+) T Cells are boosted upon ZOSTAVAX vaccination. Front Immunol 2015;6:553 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Nagaike K, Mori Y, Gomi Y, et al. . Cloning of the varicella-zoster virus genome as an infectious bacterial artificial chromosome in Escherichia coli. Vaccine 2004;22:4069–74. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.03.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cohen JI. VZV: molecular basis of persistence (latency and reactivation) : Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, Human herpesviruses: biology, therapy, and immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sen N, Mukherjee G, Arvin AM. Single cell mass cytometry reveals remodeling of human T cell phenotypes by varicella zoster virus. Methods 2015;90:85–94. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gershon AA, Chen J, Gershon MD. A model of lytic, latent, and reactivating varicella-zoster virus infections in isolated enteric neurons. J Infect Dis 2008;197(Suppl 2):S61–5. 10.1086/522149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buchbinder SP, Mehrotra DV, Duerr A, et al. . Efficacy assessment of a cell-mediated immunity HIV-1 vaccine (the step study): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, test-of-concept trial. Lancet 2008;372:1881–93. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61591-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Duerr A, Huang Y, Buchbinder S, et al. . Extended follow-up confirms early vaccine-enhanced risk of HIV acquisition and demonstrates waning effect over time among participants in a randomized trial of recombinant adenovirus HIV vaccine (Step Study). J Infect Dis 2012;206:258–66. 10.1093/infdis/jis342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lajoie J, Kimani M, Plummer FA, et al. . Association of sex work with reduced activation of the mucosal immune system. J Infect Dis 2014;210:319–29. 10.1093/infdis/jiu023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lajoie J, Juno J, Burgener A, et al. . A distinct cytokine and chemokine profile at the genital mucosa is associated with HIV-1 protection among HIV-exposed seronegative commercial sex workers. Mucosal Immunol 2012;5:277–87. 10.1038/mi.2012.7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nkwanyana NN, Gumbi PP, Roberts L, et al. . Impact of human immunodeficiency virus 1 infection and inflammation on the composition and yield of cervical mononuclear cells in the female genital tract. Immunology 2009;128:e746–57. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03077.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carnathan DG, Wetzel KS, Yu J, et al. . Activated CD4+CCR5+ T cells in the rectum predict increased SIV acquisition in SIVGag/Tat-vaccinated rhesus macaques. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:518–23. 10.1073/pnas.1407466112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mir KD, Gasper MA, Sundaravaradan V, et al. . SIV infection in natural hosts: resolution of immune activation during the acute-to-chronic transition phase. Microbes Infect 2011;13:14–24. 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.09.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang ZQ, Wietgrefe SW, Li Q, et al. . Roles of substrate availability and infection of resting and activated CD4+ T cells in transmission and acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:5640–5. 10.1073/pnas.0308425101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Meditz AL, Haas MK, Folkvord JM, et al. . HLA-DR+ CD38+ CD4+ T lymphocytes have elevated CCR5 expression and produce the majority of R5-tropic HIV-1 RNA in vivo. J Virol 2011;85:10189–200. 10.1128/JVI.02529-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rerks-Ngarm S, Pitisuttithum P, Nitayaphan S, et al. . Vaccination with ALVAC and AIDSVAX to prevent HIV-1 infection in Thailand. N Engl J Med 2009;361:2209–20. 10.1056/NEJMoa0908492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kim JH, Rerks-Ngarm S, Excler JL, et al. . HIV vaccines: lessons learned and the way forward. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2010;5:428–34. 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833d17ac [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Brown SA, Surman SL, Sealy R, et al. . Heterologous prime-boost HIV-1 vaccination regimens in pre-clinical and clinical trials. Viruses 2010;2:435–67. 10.3390/v2020435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Haynes BF. New approaches to HIV vaccine development. Curr Opin Immunol 2015;35:39–47. 10.1016/j.coi.2015.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McMichael AJ, Haynes BF. Lessons learned from HIV-1 vaccine trials: new priorities and directions. Nat Immunol 2012;13:423–7. 10.1038/ni.2264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017391supp001.pdf (139.4KB, pdf)