Abstract

Introduction

Preterm birth accounts for more than 85% of all perinatal complications and deaths. Seventy-five per cent of early preterm births (EPTBs) occur spontaneously and without identifiable risk factors. The need for a broadly applicable, effective strategy for primary prevention is paramount. Secondary outcomes from the docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) to Optimise Mother Infant Outcome trial showed that maternal supplementation until delivery with omega-3 (ω-3) long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid (LCPUFA), predominantly as DHA, resulted in a 50% reduction in the incidence of EPTB and an increase in the incidence of post-term induction or post-term prelabour caesarean section due to extended gestation. We aim to determine the effectiveness of supplementing the maternal diet with ω-3 LCPUFA until 34 weeks’ gestation on the incidence of EPTB.

Methods and analysis

This is a multicentre, parallel group, randomised, blinded and controlled trial. Women less than 20 weeks’ gestation with a singleton or multiple pregnancy and able to give informed consent are eligible to participate. Women will be randomised to receive high DHA fish oil capsules or control capsules without DHA. Capsules will be taken from enrolment until 34 weeks’ gestation. The primary outcome is the incidence of EPTB, defined as delivery before 34 completed weeks’ gestation. Key secondary outcomes include length of gestation, incidence of post-term induction or prelabour caesarean section and spontaneous EPTB. The target sample size is 5540 women (2770 per group), which will provide 85% power to detect an absolute reduction in the incidence of preterm birth of 1.16% (from 2.45% to 1.29%) between the DHA and control group (two sided α=0.05). The primary analysis will be based on the intention-to-treat principle.

Trial registration number

Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry Number: 2613001142729; Pre-results.

Keywords: preventive medicine, pregnancy, preterm birth, omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, ocosahexaenoic acid, maternal diet

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is the largest randomised controlled trial with adequate power that is designed to assess the effect of omega-3 (ω-3) long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid (LCPUFA) supplementation in pregnancy on the incidence of early preterm birth (EPTB) as the primary outcome.

The study uses an innovative intervention strategy, which is unique compared with other trials in this field. The intervention targets the period before and during the time when EPTB is likely to occur and it is ceased at 34 weeks’ gestation, at which time EPTB has been prevented. This strategy may reduce the risk of post-term birth.

The study assesses maternal LCPUFA status at baseline and at the end of the intervention period, providing an independent biomarker of compliance, in addition to maternal self-report and capsule back count.

The study is conducted in an industrialised setting where intake of ω-3 LCPUFA is low. Findings from this study may not be applicable in populations with high intake of ω-3 LCPUFA.

Introduction

Background

Preterm birth, or birth before 37 completed weeks of pregnancy, is the leading cause of death in newborns, accounting for more than 85% of all perinatal complications and death.1 It is estimated that 10% of births (13 million babies each year worldwide) are preterm and 20% of these preterm births occur before 34 weeks, these being referred to as early preterm birth (EPTB). It is EPTB that is the major cause of perinatal mortality, serious neonatal morbidity and moderate to severe childhood disability in developed countries.2–4 Effective, broadly applicable primary prevention strategies to reduce the risk of EPTB are lacking.

Prostaglandins and other lipid mediators derived from omega-6 (ω-6) and omega-3 (ω-3) fatty acids play essential roles in normal and pathologic initiation of labour.5 6 The fetoplacental unit is supplied with long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFA) from the maternal circulation, which is influenced by maternal LCPUFA intake and endogenous synthesis. Prostaglandins derived from ω-6 arachidonic acid are countered by those derived from ω-3 LCPUFA within the same tissues. The balance between the metabolites of ω-3 and ω-6 fatty acids plays an important role in the maintenance of normal gestation length and is a critical element in cervical ripening and the initiation of labour.7 If local production of ω-6 derived prostaglandins within the fetoplacental unit is too high, or local accumulation of ω-3 LCPUFA is too low, the cervix may prematurely ripen and uterine contractions increase, which may in turn lead to preterm birth or EPTB.

Current Western diets are low in ω-3 LCPUFA.8 The Suppl 20 WHO recommends an intake of 300 mg/day of ω-3 LCPUFA for pregnant women; however, the median intake in Australian women of childbearing age is only 29 mg/day9 compared with 1000 mg/day in women from nations with high-fish consumption such as Japan, Korea and Norway. The intake of ω-3 LCPUFA is further reduced among pregnant women due to a reduced intake of all fish following advisories for pregnant women to avoid specific long-lived predatory fish due to the concern about mercury contamination.10 The level of ω-3 LCPUFA intake estimated to achieve normal rises in the fetoplacental unit for the maintenance of a full-term pregnancy is well above the intake of many pregnant women, highlighting a potential insufficiency for the uterus and fetoplacental unit. Optimising ω-3 LCPUFA intake in pregnancy may restore the balance between ω-3 and ω-6 fatty acids and reduce the risk of preterm birth.

At the time the trial started, only two of the six included trials in the Cochrane review11 of marine oil supplementation in pregnancy reported the effect on EPTB. Both trials12 13 were conducted in high-risk pregnancies designed to assess the effect of ω-3 LCPUFA supplementation to prevent reoccurrence of intrauterine growth restriction, preterm birth or pregnancy induced hypertension. From these two relatively small trials (total of 860 women), it was seen that women allocated to receive fish oil had a lower risk of EPTB compared with control (relative risk (RR) 0.69, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.99). Systematic reviews11 14 15 have shown no difference in the incidence of antepartum hospitalisation, caesarean section, eclampsia or other serious maternal morbidity between treatment (ω-3 LCPUFA supplements) and control groups. The RR of miscarriage, stillbirth and neonatal death also did not differ between the groups.11 14 15 None of the included trials reported the effect of ω-3 LCPUFA supplementation on EPTB in the general population of pregnant women.

The strongest evidence to support the efficacy of ω-3 LCPUFA supplementation to reduce EPTB comes from our docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) to Optimise Mother Infant Outcome (DOMInO) trial,16 the largest trial to date of ω-3 LCPUFA supplementation in pregnancy. DOMInO was designed to assess the effect of ω-3 LCPUFA supplementation during the last half of pregnancy on the prevalence of postnatal depression in women and on early childhood neurodevelopmental outcomes. We enrolled 2399 women from five perinatal centres around Australia who were randomly assigned to receive identical looking capsules containing either fish oil concentrate (900 mg ω-3 LCPUFA/day) or a blend of vegetable oils (no ω-3 LCPUFA) from 20 weeks’ gestation until birth. In a prespecified secondary analysis, there were fewer EPTB in the ω-3 LCPUFA supplemented group compared with control (1.09% vs 2.25%, adjusted RR 0.49, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.94, p=0.03) and fewer admissions to level three intensive care (1.75% vs 3.08%, RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.97, p=0.04). Similar findings were reported in a smaller US trial (n=301), the Kansas University DHA Outcomes (KUDOS) Study,17 which showed that supplementation with 600 mg of DHA daily from mid-pregnancy until birth resulted in a reduction in the incidence of EPTB (0.6% vs 4.8%, p=0.025). The effect of DHA supplementation in pregnancy in lowering the risk of EPTB observed in both the DOMInO and KUDOS trials is consistent with the Cochrane review18 published before these two trials. Despite these encouraging findings, results have been viewed with caution by researchers and clinicians because EPTB was a secondary outcome of the DOMInO and KUDOS trials. A recent update to this Cochrane review (publication pending) includes 54 randomised trials with a total of >15 000 participants. Results show a clear reduction in EPTB (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.81; 9 randomised controlled trials (RCTs); n=4351) for supplementation compared with placebo.19 Our DOMInO trial supports the safety data from previous systematic reviews; however, there were more post-term births requiring obstetric intervention (induction or caesarean section) in the ω-3 LCPUFA supplemented group compared with control (17.59% vs 13.72%, adjusted RR 1.28, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.54, p=0.01). To determine both efficacy and safety of this intervention, we therefore plan to undertake a further trial with adequate power to assess the effect of ω-3 LCPUFA supplementation in pregnancy on EPTB as the primary outcome, with a unique design ceasing the intervention at 34 weeks’ gestation to reduce the risk of post-term birth.

Hypotheses

Optimising ω-3 LCPUFA intake in pregnancy will lead to lower risk of EPTB.

Methods

Trial design

The ORIP trial is designed as a randomised, controlled, clinician, researcher and participant/family blinded, multicentre trial with two parallel groups and a primary outcome of incidence of EPTB, defined as delivery before 34 completed weeks’ gestation.

Participating centres

The sponsoring institution and Trial Coordinating Centre is the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute based at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Adelaide, South Australia. The trial is being conducted in the following six centres in Australia: Women’s & Children’s Hospital, Flinders Medical Centre and Lyell McEwin Hospital in South Australia; Joondalup Health Campus, Western Australia; Werribee Mercy Hospital, Werribee, Victoria and Mater Mothers Hospital, Brisbane, Queensland.

Study population

Participants are pregnant women less than 20 weeks’ gestation.

Eligibility criteria

Pregnant women are approached by trained clinical trial personnel in the antenatal clinic of participating centres.

Inclusion criteria

Women must meet both the following criteria to be enrolled in this study:

Singleton or multiple pregnancy and less than 20 weeks’ gestation.

Able to give informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

Women must not have any of the following criteria to be enrolled in this study:

Fetus with a known abnormality.

Taking dietary supplements containing LCPUFA >150 mg/day.

Taking dietary supplements containing LCPUFA <150 mg/day and are not willing to stop.

Bleeding disorders where fish oil is contraindicated or on anticoagulant therapy.

History of drug or alcohol abuse.

Study treatments

Participating women will be randomised to high-DHA fish oil capsules or vegetable oil capsules. The study capsules are identical in colour, size, shape and packaging and are iso-caloric. Women will be asked to consume three capsules per day.

DHA capsules

Each 500 mg DHA enriched fish oil capsule contains approximately 300 mg of ω-3 LCPUFA. Women will be asked to take three capsules per day orally, which will provide approximately 1 g of ω-3 LCPUFA (800 mg of DHA and 100 mg of eicosapentaenoic acid per day. The remaining portion of oil consists of monounsaturated and saturated fatty acids.

Control capsules

The control capsules (also 500 mg in weight) contain a blend of vegetable oils (canola, sunflower and palm oils) with a trace of tuna oil (12.6 mg ω-3 LCPUFA) to assist with blinding. This blend of oil matches the fatty acid composition of the typical Australian diet.

Manufacture of study capsules

The active and control capsules are manufactured in a licensed facility (licensed according to the Code of Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)) and have been donated to the trial by Efamol Ltd/Wassen International Ltd. The capsules are packaged and labelled in accordance with GMP including an individual product identifier (ID), batch number, expiry date and the statement ‘for clinical trial use only’. The pharmacist or the investigator’s designee maintains accurate records of the receipt of all study capsules, including dates of receipt. Unused study capsules will be destroyed in compliance with applicable regulations.

Monitoring adherence to study treatment

Research personnel in each centre will maintain regular contact with participating women to monitor and encourage capsule adherence and study compliance and answer any questions as they arise. Women are asked to return unused capsules at the final study visit (34 weeks’ gestation) and the proportion of capsules returned serves as an additional measure of compliance. A finger prick blood specimen collected from the woman at this final visit will be used in fatty acid analysis as an independent biomarker of adherence. All clinical care for women involved in this trial will be undertaken by her designated obstetric/midwifery care provider.

Outcome measures

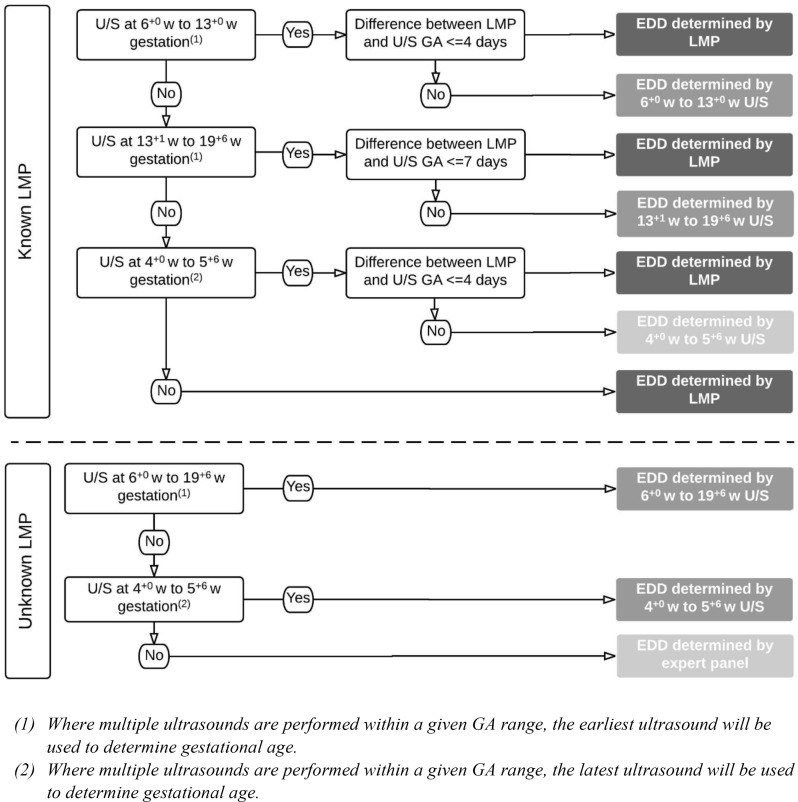

The primary outcome of this trial is the incidence of EPTB, defined as delivery before 34 completed weeks’ gestation. Gestational age (GA) in days at delivery for primary and secondary outcomes will be determined from the estimated date of delivery (EDD) using the equation (280 – (EDD – date of birth)). EDD will be determined using a combination of maternal menstrual dating and ultrasound dating in accordance with established obstetric practice, as outlined in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for determining EDD. EDD, estimated date of delivery; GA, gestational age; LMP, last menstrual period; U/S ultrasound; w, weeks.

Key secondary outcomes

Length of gestation

Post-term induction or post-term prelabour caesarean section

Preterm birth (<37 completed weeks)

Spontaneous EPTB

Birth weight

Low birth weight (<2500 g)

Admission to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit

Perinatal death (stillbirth and death within first 28 days of birth)

Other outcomes

Spontaneous preterm birth, prelabour rupture of membranes, prelabour, preterm rupture of membranes.

Birth length, birth head circumference, small for GA, very small for GA, large for GA, very large for GA.

The length of hospital stay of infants and mothers, length of admission in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit.

Pregnancy and labour outcomes including gestational diabetes, pregnancy-induced hypertension, pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, maternal use of antibiotics, caesarean section, estimated blood loss at birth and postpartum haemorrhage.

Incidence of serious adverse event (SAE) defined as maternal, neonatal or fetal deaths (stillbirth); fetal loss (miscarriage); maternal admissions to intensive care; admissions to intensive care for infants born after 34 weeks’ gestation and major congenital anomalies.

Neonatal complications including jaundice (requiring phototherapy), hypoglycaemia (requiring intravenous dextrose infusion), neonatal convulsion, brain injury (including intraventricular haemorrhage), retinopathy of prematurity, sepsis, necrotising enterocolitis and duration of supplemental oxygen. The definitions and classifications of these neonatal complications are in accordance with the Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network Data Dictionary.20

Other side effects and tolerability of DHA supplementation assessed through data collected in the case report form (CRF).

Participant timeline

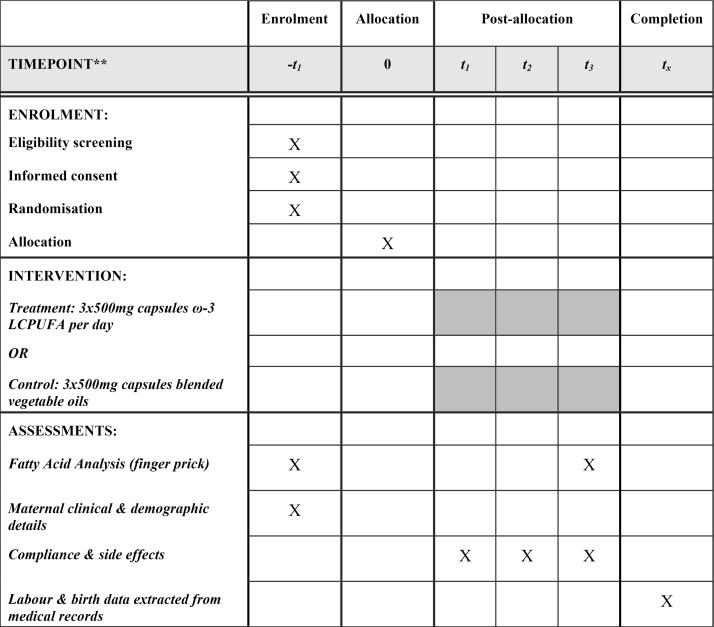

Women will be randomised and commence study treatment capsules from enrolment (<20 weeks’ gestation) until 34 weeks’ gestation or birth, whichever occurs first. At enrolment, following informed consent and prior to commencement of study treatment, research personnel will collect a finger prick blood sample for baseline fatty acid status. The woman’s height and weight will be measured and baseline clinical and demographic data collected. Research personnel will contact the participant 2 weeks following the enrolment visit and again when the woman is 28 weeks’ gestation to ascertain capsule adherence and record adverse events. At 34 weeks’ gestation, participating women will attend a clinic appointment for collection of a finger prick blood sample for fatty acid analysis and unused capsules are returned and counted. Six weeks following delivery, research personnel will extract details of pregnancy, labour and birth from the woman and her baby’s medical records for primary and secondary outcome data; see figure 2 for a summary of the ORIP trial schema.

Figure 2.

ORIP trial schedule. **–t1=<20 weeks’ gestation; t1=2 weeks’ post-randomisation and allocation; t2=28 weeks’ gestation; t3=34 weeks’ gestation or birth, whichever occurs first; tx=6 weeks post-estimated due date. ω-3 LCPUFA, omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid.

Sample size

Our previous trial of DHA supplementation of pregnant women, the DOMInO trial,16 included women with singleton pregnancies and treatment resulted in a 1.16% absolute reduction (from 2.25% to 1.09%) in the incidence of EPTB. This reduction occurred in the presence of non-adherence resulting from women assigned to the intervention failing to take the trial supplements as directed, and control women taking prenatal supplements containing low dose ω-3 LCPUFA. Similar levels of non-adherence are expected in the ORIP trial. Inclusion of women with multiple pregnancies in the ORIP trial is expected to result in a small increase in the incidence of EPTB in both treatment groups, since EPTB is more common in multiple pregnancies. To demonstrate an absolute reduction in the incidence of EPTB of 1.16% (from 2.45% to 1.29%) with 85% power and overall two-sided alpha=0.05 (alpha=0.049 at the final analysis), a sample size of 2631 per group (ie, 5262 total) is required. Allowing for a loss to follow-up of 5%, a total of 5540 women is required to ensure adequate power for the primary outcome. Since EPTB is a mother level outcome, the sample size calculations define the number of mothers that should be recruited and no adjustment for clustering due to multiple pregnancies is required for this outcome.

Recruitment

Women will be approached to enter the trial by research staff at the time of attending their routine antenatal visit at one of the centres involved. Pregnant women will also be informed about the trial by display of approved advertising material which will be circulated in hard copy and via social media avenues. A participant information sheet describing the purpose of the study, the procedures to be followed and the risks and benefits of participation will be explained to interested women. Following a screening process to ensure inclusion and exclusion criteria are met, the investigator or nominee will conduct the informed consent discussion and will check that information provided is understood and answer any questions about the study. A record of all women screened and their enrolment status will be maintained to adhere to the consolidated standards for the reporting of randomised controlled trials.21 Women may withdraw their involvement in the trial at any time and, wherever possible, the reason for withdrawal will be recorded.

Randomisation procedures

Once the consent process has been documented by signing of the written consent form, the participant will be randomised using a web-based randomisation service. Stratification will be by centre and current supplement use (no LCPUFA vs ≤150 mg LCPUFA/day prior to randomisation). Allocation follows a computer-generated randomisation schedule with balanced variable blocks, prepared using ralloc.ado V.3.7.5 in Stata V.12.1 by an independent statistician who is not involved with trial participants or data analysis. A unique six-digit study ID and a study pack with a unique product ID are assigned. The study ID identifies the randomised woman and the product ID identifies a pack of five bottles of either active or control capsules, prepackaged corresponding to the randomisation schedule.

Blinding

Participants and their family, care providers, data collectors, outcome assessors, research personnel and data analysts will all be blinded to randomisation group. The intervention and control capsules are identical in shape, size, colour, packaging and labelling and uniquely identified only by the product ID. In the DOMInO trial, we identified that more women in the intervention group correctly guessed their group allocation. We therefore added a small amount of tuna oil (5%) to the control capsules to enhance blinding of study participants. The randomisation code for an individual participant may be unblinded in an emergency if the site investigator decides a participant cannot be adequately treated without knowing their study treatment allocation. The principal investigator will be notified and must contact the Data Management and Analysis Centre, where the randomisation list is securely stored. The time, date, study ID of the participant and reason for unblinding must be documented and events leading to the emergency unblinding will be recorded.

Data collection and trial management

A purpose-built web-based clinical trial management information system (CTMS) with password protection and defined user-level access is used to facilitate trial management. A record of all women approached, screened for eligibility and consented is recorded in real time in the CTMS. Once consented and randomised, the CTMS automatically calculates study milestones for each participant. This information is readily available for clinical trial staff to enable scheduling of appointments and sample collection. Data entered by individual study centres is routinely scrutinised by the Coordinating Centre to monitor protocol adherence and study progress. Summary reports including screening data, enrolment, appointment attendance, sample collection, SAEs and study completion are generated from the CTMS and reviewed at monthly trial steering committee meetings. Site monitoring visits to ensure compliance with good clinical practice and the study protocol are conducted at site start-up and then 6 monthly or as required to ensure the integrity of the trial.

Data are collected by trained clinical trial staff at each participating centre onto carbon copy paper CRFs. Carbon copies of the completed CRF remain on site at participating centres with original copies being mailed to the Data Management and Analysis Centre at the University of Adelaide for data management including data entry and data cleaning. Data validity checks are completed by data entry personnel and data queries posted to the CTMS for resolution by participating centres. Data queries generated by statisticians during regular blinded reviews of data quality and batch checks are also managed through the CTMS. Electronic data are stored on secure servers at the Data Management and Analysis Centre and released only to persons authorised to receive those data. Following study completion, copies of study documents are retained at each study site or in archives. Documents held at the Coordinating Centre will be retained for at least 30 years after study completion in line with the data retention schedules for research involving minors.22 At the completion of this time, documentation will be destroyed using confidential document disposal. Electronic data will be stored indefinitely on secure servers with access only granted to authorised study personnel.

Statistical methods

All participants will be analysed according to the group to which they were randomised (intention-to-treat principle) for the primary analysis. The primary outcome of EPTB will be compared between intervention and control groups using a log binomial regression model. Adjustment will be made for the stratification variables centre and supplements, and results will be presented as a RR with CI and two-sided p value. Statistical significance will be assessed at an alpha of 0.049 to account for the prespecified interim analysis (see below) using the O’Brien-Fleming approach. Key secondary and other outcomes will be compared between treatment groups using log binomial regression models for binary outcomes and linear regression models for continuous outcomes with no adjustment for multiple comparisons. Clustering due to multiple pregnancies and repeat participation in the trial will be taken into account where applicable using generalised estimating equations. Secondary analyses will be performed for the primary outcome and related key secondary and other outcomes to test for evidence of effect modification by pregnancy status (single vs multiple pregnancy), history of preterm birth and baseline DHA. Missing data will be addressed using multiple imputation under a missing at random assumption. Sensitivity analyses will be performed using the original unimputed data. A secondary per-protocol analysis will be performed for the primary outcome including only women who were compliant with the protocol. Two separate definitions of compliance will be used. First, women will be considered compliant if they returned their remaining capsules at the end of the trial and consumed at least 75% of the number of capsules expected to be consumed. Second, women will be considered compliant if they had the 28-week telephone contact and reported they had missed less than 7 capsules in the last week out of the recommended 21 capsules.

All analyses will follow a prespecified statistical analysis plan. There is a single planned interim analysis of the primary outcome to be performed after data collection is complete for the first 50% of the target number of randomised participants.

Data monitoring

An independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) has been set up to review the progress of the trial and provide feedback to the Trial Steering Committee. The DMC reviews general study progress (recruitment, compliance, loss to follow-up), the EPTB event rate and key secondary/safety outcomes. The committee meets annually or as required and consists of a neonatologist, obstetrician and statistician with clinical trials expertise. The DMC will be responsible for reviewing the results of the interim analysis.

An independent (blinded) SAE Committee has been established to review SAEs. There are no SAEs which would be anticipated as a unique consequence of participation in the trial; however, all deaths, admissions to an intensive care unit of mothers or of infants born after 34 completed weeks’ gestation and major congenital abnormalities are to be reported. The SAE Committee includes experts in obstetrics, neonatology, pathology and midwifery who are not involved in the trial. The primary role of the SAE Committee is to review all SAEs and determine whether there is any likelihood that involvement in the trial could have contributed to the event. Determinations of causality will be made from medical records retrieved for this purpose. This committee meets quarterly or as required.

Ethics and dissemination

Research ethics approval

This protocol and the informed consent and participant information document have been approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of each study site. Women’s and Children’s Health Network HREC (Coordinating HREC & Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Adelaide; Southern Adelaide Clinical HREC, Adelaide, South Australia); Mercy Health HREC (Werribee Mercy Hospital, Werribee, Victoria); Mater Mothers’ Hospital, Brisbane, Queensland; University of Notradame, Joondalup Health Campus, Joondalup, Western Australia. Any subsequent modifications will be reviewed and approved by the HREC and governance of each study site. The study will be conducted in compliance with the current approved version of the protocol. Any change to the protocol document or informed consent form that affects the scientific intent, study design, patient safety or may affect a participant’s willingness to continue participation in the study will be considered a major amendment. All such amendments will be submitted to the HREC for approval. Any other changes to the protocol (such as administrative changes to dates and study personnel) will be considered minor amendments and will be notified to the HREC as appropriate. Study findings will be disseminated via peer-reviewed publication, conference presentations, informing participants with a lay summary and the wider community through social media.

Confidentiality

Participant confidentiality is strictly held in trust by the participating investigators, research staff and their agents. This confidentiality is extended to cover testing of biological samples in addition to the clinical information relating to participants. The study protocol, documentation, data and all other information generated will be held in strict confidence. No information concerning the study or the data will be released to any unauthorised third party, without prior written approval of the Coordinating Centre. The Coordinating Centre and regulatory authorities may inspect all documents and records required to be maintained by the investigator, including but not limited to, medical records and pharmacy records for the infants in this study subject to individuals having obtained approval/clearance through State/National Governments and HREC as required by local laws. The study site will permit access to such records. Clinical information will not be released without written permission of the parent/guardian, except as necessary for monitoring by HREC or regulatory agencies.

Dissemination plan

Study findings will be submitted for peer-reviewed publication and for presentation at appropriate local and international conferences. In addition, study findings will be disseminated to participants through a one-page lay summary. Results will be made available to the wider community through social media avenues and the South Australian Health & Medical Research Institute website.

Trial status

This enrolment phase of this trial completed on 27 April 2017 with successful attainment of sample size (n=5544). Completion of study follow-up appointments and collection of labour and birth data from participant medical records will be completed by December 2017.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the research and clinical teams at all participating study centres.

Footnotes

Contributors: MM, JQ, RG, AM and SJZ conceived and designed the study with KB contributing to ongoing study implementation and management. LY provided statistical expertise. SJZ and KB wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to refinement of the study protocol and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia, grant number 1050468. The study product is donated by Efamol Ltd/Wassen Intl Ltd. An NHMRC Fellowship supports RG (Senior Principal Research Fellow 1046207) and MM (Principal Research Fellow 1061704) and LY (Early Career Research Fellow 1052388). The funding bodies had no role in the design of this study and will not have any role during the conduct of the study, data collection, study management, analyses and interpretation of the data or in the writing, review or approval publications. The contents of the published material are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not reflect the views of the NHMRC.

Competing interests: The authors declare: financial support for the submitted work from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Australia (Project Grant 1050468). RG serves on a scientific advisory board for Fonterra; MM serves on scientific advisory boards for Nestle and Fonterra. Associated Honoraria for RG and MM are paid to their institutions to support conference travel and continuing education for postgraduate students and early career researchers. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from this case description/these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) of each study site.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Once the primary trial is published, ORIP data will be available for data sharing. Please send requests to Maria Makrides (maria.makrides@sahmri.com) and Karen Best (karen.best@adelaide.edu.au).

References

- 1. Thornton S. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences and Prevention. The Obstetrician & Gynaecologist 2008;10:280–80. 10.1576/toag.10.4.280b.27453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lumley J. Defining the problem: the epidemiology of preterm birth. BJOG 2003;110 (Suppl 20):3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, et al. . Births: final data for 2004. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2006;55:1–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pretorius C, Jagatt A, Lamont RF. The relationship between periodontal disease, bacterial vaginosis, and preterm birth. J Perinat Med 2007;35:93–9. 10.1515/JPM.2007.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gravett MG. Causes of preterm delivery. Semin Perinatol 1984;8:246–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karim SM. The role of prostaglandins in human parturition. Proc R Soc Med 1971;64:10–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brazle AE, Johnson BJ, Webel SK, et al. . Omega-3 fatty acids in the gravid pig uterus as affected by maternal supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids. J Anim Sci 2009;87:994–1002. 10.2527/jas.2007-0626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prescott SL. Early-life environmental determinants of allergic diseases and the wider pandemic of inflammatory noncommunicable diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;131:23–30. 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Meyer BJ, Mann NJ, Lewis JL, et al. . Dietary intakes and food sources of omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Lipids 2003;38:391–8. 10.1007/s11745-003-1074-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oken E, Kleinman KP, Berland WE, et al. . Decline in fish consumption among pregnant women after a national mercury advisory. Obstet Gynecol 2003;102:346–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Escamilla-Nuñez MC, Barraza-Villarreal A, Hernández-Cadena L, et al. . Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation during pregnancy and respiratory symptoms in children. Chest 2014;146:373–82. 10.1378/chest.13-1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bulstra-Ramakers MT, Huisjes HJ, Visser GH. The effects of 3g eicosapentaenoic acid daily on recurrence of intrauterine growth retardation and pregnancy induced hypertension. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995;102:123–6. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1995.tb09064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olsen SF, Secher NJ, Tabor A, et al. . Randomised clinical trials of fish oil supplementation in high risk pregnancies. Fish Oil Trials In Pregnancy (FOTIP) Team. BJOG 2000;107:382–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Horvath A, Koletzko B, Szajewska H. Effect of supplementation of women in high-risk pregnancies with long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids on pregnancy outcomes and growth measures at birth: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Nutr 2007;98:253–9. 10.1017/S0007114507709078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Szajewska H, Horvath A, Koletzko B. Effect of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation of women with low-risk pregnancies on pregnancy outcomes and growth measures at birth: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;83:1337–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Makrides M, Gibson RA, McPhee AJ, et al. . Effect of DHA supplementation during pregnancy on maternal depression and neurodevelopment of young children: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2010;304:1675–83. 10.1001/jama.2010.1507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Carlson SE, Colombo J, Gajewski BJ, et al. . DHA supplementation and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Clin Nutr 2013;97:808–15. 10.3945/ajcn.112.050021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Makrides M, Duley L, Olsen SF. Marine oil, and other prostaglandin precursor, supplementation for pregnancy uncomplicated by pre-eclampsia or intrauterine growth restriction. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006:CD003402 10.1002/14651858.CD003402.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Philippa Middleton JG, Shepherd E, Makrides M. Omega-3 supplementation during pregnancy: an updated Cochrane review. J Paediatr Child Health 2017;53:68–9.27586066 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network A. Australian and New Zealand Network Data Dictionary, Definitions for audit Australian and New Zealand Network Data Dictionary. Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. CONSORT. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel group randomized trials. BMC Med Res Methodol 2001;1:2 10.1186/1471-2288-1-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Governance R. Site Specific Assessment: Submission Guidelines: Women’s and Children’s Health Network RG, ed. Site Specific Assessment: Submission Guidelines. Adelaide: Women’s and Children’s Health Network, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.