Abstract

Objectives

Comprehensive epidemiological and economic studies of gastric cancer (GC) in Panama are limited. This study aims to evaluate the association between socioeconomic and clinical variables with survival, describe the survival outcomes according to clinical stage and estimate the direct costs associated to GC care in a Panamanian population with GC.

Design and setting

A retrospective observational study was conducted at the leading public institution for cancer treatment in Panama.

Participants

Data were obtained from 611 records of patients diagnosed with gastric adenocarcinoma (codes C16.0–C16.9 of the International Classification of Diseases 10th revision), identified between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2015.

Methods

Cox proportional hazards models were used to calculate HRs with 95% CI to examine associations between the variables and survival. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to assess overall and stage-specific survival. Direct costs (based on 2015 US$) were calculated per patient using standard costs provided by the institution for hospital admission (occupied bed-days), radiotherapy, surgery and chemotherapy, yielding total and overall mean costs (OMC). A comparison of OMC between groups (sex, social security status, clinical stage) was performed applying the bootstrap method with a t-test of unequal variances.

Results

An increased risk of dying was observed for patients without social security coverage (HR: 2.02; 95% CI 1.16 to 3.53), overlapping tumours (HR: 1.50; 95% CI 1.02 to 2.22), poorly differentiated tumours (HR: 2.27; 95% CI 1.22 to 4.22) and stage IV disease (HR: 5.54; 95% CI 3.38 to 9.08) (adjusted models). Overall 1-year survival rate was 41%. The estimated OMC of GC care per patient was 4259 US$. No statistically significant differences were found in OMC between groups.

Conclusions

Socioeconomic disparities influence GC outcomes and healthcare utilisation. Policies addressing healthcare disparities related to GC are needed, as well as in-depth studies evaluating barriers of access to GC-related services.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Survival, Health care costs, Panama

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Data regarding patient deaths were ascertained with the National Mortality Registry.

The use of actual chemotherapeutic doses administered allowed a more accurate calculation of medication costs.

Applying the bootstrap method for mean cost comparison purposes provided us with a more flexible tool to compare costs.

This study encompassed patients from a single cancer institution and our results cannot be extrapolated to the whole population; however, the National Oncology Institute of Panama is the biggest and main cancer referral public hospital in the country.

There was a considerable amount of under-reporting and missing variables such as incomplete data regarding chemotherapy protocol sessions, resource use and outpatient expenses, which most likely led to underestimation of costs.

Introduction

Latin America presents one of the highest incidences of Gastric Cancer (GC) worldwide.1 In 2011, GC was responsible for the sixth highest incidence and the highest mortality rate from cancer in Panama.2 Although GC treatment is evolving rapidly at the expense of increasing costs of care, there is scarcity of comprehensive epidemiological and economical studies of GC in the region.3

Understanding the epidemiology of GC and its costs in low and middle-income countries is a crucial step to addressing the burden of GC and will guide disease surveillance, screening, prevention activities as well as healthcare resource allocation. Thus, the aims of this study were to evaluate the association between socioeconomic and clinical variables with survival, describe the survival outcomes according to clinical stage and describe the direct costs associated to GC care in a Panamanian population with GC.

Methods

Study population

A descriptive, hospital-based retrospective study was conducted at the National Oncology Institute (NOI). The NOI is the leading public institution for cancer treatment in Panama, receiving cases referred from all over the country.4 5

Data derived from patient records (electronic and paper based) with a histopathological diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma having their first appointment at the NOI between 1 January 2012 and 31 December 2015 was retrieved. Cases were registered according to codes C16.0 to C16.9 based on the 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10).

A list containing 697 patients was provided by the Department of Clinical Files at the NOI. A total of 12 clinical records could not be located and were therefore excluded. Of the remaining 685 records, those with a diagnosis different from gastric adenocarcinoma were excluded (mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumours, neuroendocrine tumours, sarcomas, as well as tumours confirmed to be from a different primary site (eg, oesophageal), for a total study population of 611 patients (see online supplementary figure 1).

bmjopen-2017-017266supp001.pdf (123.4KB, pdf)

Patient deaths from 2012 to 2015 were verified with the National Mortality Registry (NMR) supplied by the National Institute of Statistics and Census of Panama (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censo (INEC)), using all-cause mortality data. This database comprises all deaths reported either from the Civil Registry or the Institute of Legal Medicine (deaths due to external causes). A recent study that assessed civil registration and vital statistics systems reported the quality of Panamanian data as high6 The research protocol was approved by the Gorgas Memorial Institute Ethics Committee and the Ministry of Health.

Study variables

Socioeconomic (sex, age at diagnosis, social security status, employment status, marital status, province of residence, ethnicity) and clinical variables (location by endoscopy, histological type, tumour grade and clinical stage) were recorded. Costs were ascertained using length of stay in hospital, surgical procedures performed, chemotherapy and radiotherapy received.

Age at diagnosis was categorised considering the cut-off value of 45 years for early onset GC (EOGC), as done in previous studies7 and age strata as reported by the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER).8 Social security status was categorised as having or not coverage by health institutions of the Panamanian Social Insurance Fund, in which a monthly amount is discounted from contributors’ salaries (active public and private workforce) to receive health coverage for them and their first-degree relatives, allowing children and unemployed adults to have coverage (beneficiaries). The Social Insurance Fund also serves as a retirement fund for workers at a certain age (retired) or in case of permanent disability (pensioners). The NOI is not an institution from the Panamanian Social Insurance Fund, but patients with social security are granted free healthcare services, while those without social security are required to pay out-of-pocket fees. Nevertheless, all patients receive the same standards of care despite their insurance status.9 Formal and informal employment groups were categorised as defined by the International Labour Office.10

Provinces of residence were grouped according to geographic proximity to the NOI and common socioeconomic characteristics,11 and categorised as Panama and Colon, Veraguas and Cocle, Herrera and Los Santos and other provinces (Bocas del Toro, Chiriqui, Darien, Guna Yala, Ngäbe-Bugle).

Anatomic location of the tumour was based on endoscopic reports and categorised as non-cardia, cardia and overlapping. Cases in which the endoscopic report could not be found in the clinical files were labelled as ‘unspecified’.12 Histological type was based on the Lauren classification (intestinal, diffuse),13 and mixed tumours were shown as a different category.14 Tumour grade was categorised using ICD for Oncology, and clinical stage was based on the seventh edition of the TNM Staging System of the American Joint Committee on Cancer, taking into consideration the first staging reported in the clinical file by the physician at the NOI.15

Type of care was defined according to hospital admission (recorded as occupied bed days), radiotherapy (number of sessions), surgery and chemotherapy. Surgery was defined as the performance of gastrectomy (total, subtotal) with lymph node resection, gastroenteric anastomosis, stent placement (oesophageal, duodenal) or exploratory laparotomy. Chemotherapy regimens for GC were based on the latest National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.

Because the intention of treatment (eg, curative vs palliative) was under-reported in the patient records, and due to the possibility of non-completion of regimens (loss to follow-up or death) or change in the regimen received (eg, progression of disease, differences between clinical tumour, node, metastases (TNM) classification and pathological TNM), expenditure on chemotherapy was calculated using actual medication doses and sessions administered on an individual basis instead of assuming completion of a single, invariable regimen.

Statistical analyses

Qualitative variables were expressed as percentages. As a complementary analysis, cases per 100 000 population were calculated for each province individually, using population data from the INEC.16 Kaplan-Meier curves were used to examine overall survival for all patients and for each clinical stage group. Median survival and median follow-up times in days were calculated and 1-year survival rates were reported. Due to the length of the study period, we were not able to calculate 5-year survival rates.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to examine the association between socioeconomic and clinical variables with survival. Crude HR and 95% CI were estimated. Adjusted models including all variables were also performed to evaluate their impact on the results obtained. Ethnicity was evaluated, however, excluded from the final model due to the high admixture of the Panamanian population. Due to statistical power, provinces of residence were grouped as previously mentioned. To avoid collinearity, we performed sensitivity analyses by running two different adjusted models, one including tumour grade but not histological type and another one including histological type but not tumour grade, observing similar point estimates. The assumption of proportional risk was verified using the Schoenfeld residuals method.

Total direct costs of care, expressed in US$, were calculated per patient and for the whole study population using standard unit costs provided by the NOI and the Ministry of Health. Since no variation in costs was seen along the 2012–2015 period, calculations were based on 2015 estimates.

Total and mean direct costs were calculated according to social security status, sex and clinical stage. Overall mean cost (OMC) comparisons among groups were performed using the bootstrap method.17 This involved repeated resampling (1000 repetitions) of the original cost data by random selection. After resampling, a t-test with unequal variances was conducted to compare means and a p value was reported.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.20.0 and Stata V.14.0.

Results

Table 1 shows the socioeconomic and clinical variables of the study population. Overall, 62.2% of the total population were men, 77.4% had social security and 34.9% were unemployed. The group of provinces of Panama and Colon reported the highest number of patients (64.5%). According to age groups, 14.7% were younger than 45 years old, whereas 26.0% were ≥75 years old. Median (IQR) age at diagnosis was 65 (52-75) years. Regarding the complementary analysis, when calculating the number of cases per 100 000 population by province separately, Herrera had 8.29 cases per 100 000, followed by Veraguas with 6.58. Among patients where ethnicity was reported (n=608), 83.2% patients were registered as Mestizo.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic and clinical variables of patients with gastric cancer treated at the National Oncology Institute 2012–2015

| Socioeconomic and clinical variables | n | % |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 231/611 | 37.8 |

| Male | 380/611 | 62.2 |

| Age | ||

| Less than 45 years | 90/611 | 14.7 |

| 45–64 years | 207/611 | 33.9 |

| 65–74 years | 155/611 | 25.4 |

| 75 years or more | 159/611 | 26.0 |

| Social security status | ||

| With social security | 473/611 | 77.4 |

| Without social security | 138/611 | 22.6 |

| Employment status* | ||

| Formal employment | 116/610 | 19.0 |

| Informal employment | 119/610 | 19.5 |

| Retired/pensioner | 162/610 | 26.6 |

| Unemployed | 213/610 | 34.9 |

| Marital status† | ||

| Married/common-law marriage | 397/610 | 65.1 |

| Single | 161/610 | 26.4 |

| Widowed | 52/610 | 8.5 |

| Province of residence | ||

| Panama and Colon | 394/611 | 64.5 |

| Veraguas and Cocle | 118/611 | 19.3 |

| Herrera and Los Santos | 57/611 | 9.3 |

| Other provinces‡ | 42/611 | 6.9 |

| Ethnicity§ | ||

| White | 71/608 | 11.7 |

| Mestizo | 506/608 | 83.2 |

| Afrocaribbean | 23/608 | 3.8 |

| Indigenous | 8/608 | 1.3 |

| Anatomic location by endoscopy | ||

| Non-cardia | 239/611 | 39.1 |

| Cardia | 69/611 | 11.3 |

| Overlapping | 281/611 | 46.0 |

| Unspecified | 22/611 | 3.6 |

| Histological type¶ | ||

| Intestinal type | 232/432 | 53.7 |

| Diffuse type | 154/432 | 35.6 |

| Mixed type | 46/432 | 10.6 |

| Tumour grade** | ||

| Well/moderately differentiated | 223/592 | 37.7 |

| Poorly differentiated | 369/592 | 62.3 |

| Clinical stage†† | ||

| I | 15/323 | 4.6 |

| II | 45/323 | 13.9 |

| III | 51/323 | 15.8 |

| IV | 212/323 | 65.6 |

*Employment status: one missing.

†Marital status: one missing.

‡Other provinces: seven from Bocas del Toro, 20 from Chiriqui, 12 from Darien, 1 from Guna Yala and 2 from Ngäbe-Bugle.

§Ethnicity: three missing.

¶Histological type: 179 missing.

**Tumour grade: only one undifferentiated, 18 missing.

††Clinical stage: 288 missing.

Based on endoscopic findings, tumours were most commonly reported as overlapping, observed in 46% of the patients. According to the histological classification, a predominance of intestinal type adenocarcinomas was observed (53.7%). Poorly differentiated tumours were observed in 62.3% of patients. Out of the 611 patients, 52.9% had the clinical stage recorded. From these cases, 4.6% were categorised as stage I, 13.9% as stage II, 15.8% and 65.6% as stage III and IV, respectively.

Mortality

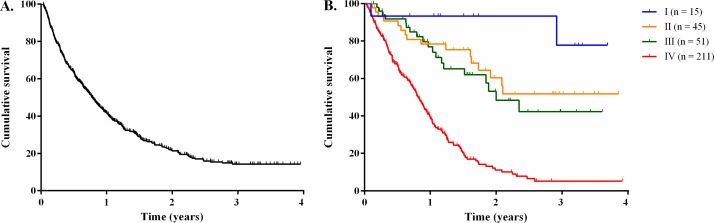

In total, n=407 (67.5%) patients died of any cause during the study period. Figure 1 shows overall and stage-specific survival curves. Overall 1-year survival rate was 41%, median survival was 287 days (9.5 months) and median follow-up was 604 days (20.1 months). Patients with stage I disease had a 1-year survival rate of 93%, whereas stages II, III and IV presented a 78%, 76% and 38% 1-year survival rate, respectively.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meler plots for overall survival (A) and stage-specific survival (B) for patients with gastric cancer treated at the National Oncology Institute 2012-2015.

Table 2 presents the associations between socioeconomic and clinical variables with deaths from all causes. In the adjusted models, patients without social security presented a higher risk of dying (HR: 2.02; 95% CI 1.16 to 3.53) compared with those with social security. Regarding anatomic location, having an overlapping tumour was related with an increased risk of dying (HR: 1.50; 95% CI 1.02 to 2.22) in comparison to non-cardia tumours. Poorly differentiated tumours were associated with a higher risk of dying (HR: 2.27; 95% CI 1.22 to 4.22) compared with well/moderately differentiated tumours, as well as those with stage IV disease (HR: 5.54; 95% CI 3.38 to 9.08) in comparison to stage I–III disease.

Table 2.

Cox proportional hazards models for the associations between socioeconomic and clinical variables with deaths from all causes in patients treated at the National Oncology Institute 2012–2015

| Socioeconomic and clinical variables | Crude HR | Adjusted HR* | ||

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | Reference | Reference | ||

| Male | 0.93 | (0.70 to 2.13) | 0.67 | (0.41 to 1.01) |

| Age | ||||

| 45–64 years | Reference | Reference | ||

| Less than 45 years | 1.43 | (0.96 to 2.13) | 0.91 | (0.53 to 1.58) |

| 65–74 years | 0.90 | (0.61 to 1.32) | 0.66 | (0.38 to 1.16) |

| 75 years or more | 1.14 | (0.78 to 1.68) | 1.68 | (0.91 to 3.10) |

| Social security status | ||||

| With social security | Reference | Reference | ||

| Without social security | 1.44† | (1.01 to 2.05)† | 2.02† | (1.16 to 3.53)† |

| Employment status‡ | ||||

| Formal employment | Reference | Reference | ||

| Informal employment | 1.04 | (0.66 to 1.63) | 1.29 | (0.68 to 2.44) |

| Retired/pensioner | 0.87 | (0.57 to 1.35) | 1.48 | (0.78 to 2.79) |

| Unemployed | 1.12 | (0.77 to 1.65) | 0.75 | (0.40 to 1.44) |

| Marital status§ | ||||

| Married/common-law marriage | Reference | Reference | ||

| Single | 1.06 | (0.76 to 1.47) | 0.87 | (0.57 to 1.32) |

| Widowed | 0.72 | (0.41 to 1.25) | 0.57 | (0.24 to 1.37) |

| Province | ||||

| Panama and Colon | Reference | Reference | ||

| Veraguas and Cocle | 0.87 | (0.58 to 1.32) | 0.86 | (0.50 to 1.47) |

| Herrera and Los Santos | 0.62 | (0.36 to 1.07) | 0.71 | (0.33 to 1.52) |

| Other provinces | 0.82 | (0.48 to 1.41) | 1.06 | (0.48 to 2.33) |

| Anatomic location by endoscopy¶ | ||||

| Non-cardia | Reference | Reference | ||

| Cardia | 1.30 | (0.78 to 2.19) | 0.94 | (0.42 to 2.13) |

| Overlapping | 1.34 | (0.99 to 1.83) | 1.50 † | (1.02 to 2.22)† |

| Histological type** | ||||

| Intestinal type | Reference | Reference | ||

| Diffuse type | 1.64† | (1.13 to 2.40)† | 0.79 | (0.43 to 1.47) |

| Mixed type | 2.12† | (1.31 to 3.44)† | 1.57 | (0.80 to 3.07) |

| Tumour grade†† | ||||

| Well/moderately differentiated | Reference | Reference | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 1.91† | (1.38 to 2.65)† | 2.27† | (1.22 to 4.22)† |

| Clinical stage | ||||

| I–III | Reference | Reference | ||

| IV | 4.37† | (3.02 to 6.33)† | 5.54† | (3.38 to 9.08)† |

*Adjustments were performed including all the covariates.

†p <0.05.

‡Employment status: one missing.

§Marital status: one missing.

¶Anatomic location: 11 missing.

**Histological type: 83 missing.

††Tumour grade: nine missing.

Cost

A total of 524 patients (85.8%) received any type of care, for an overall total cost of US$2 231 728 and an OMC per patient of US$4259 (95% CI 3915 to 4603), as shown in table 3. Baseline characteristics of the 87 patients (14.2%) that did not receive any type of care are shown in online supplementary table 1. When stratifying patients by type of care, 73.5% were admitted to the NOI, 66.4% were given chemotherapy, 30.3% underwent a surgical procedure and 18% received radiotherapy. The highest expenses were attributed to hospital admissions (US$1 156 460). Chemotherapy accounted for the second highest total cost (US$652 370), being three times greater than the total cost of radiotherapy (US$206 872). However, when comparing mean costs, radiotherapy exceeded chemotherapy by US$274 per patient. For surgical procedures the total cost was US$216 026, representing 9.7% of the overall cost.

Table 3.

Direct cost estimates (total and means) according to type of care received in patients with gastric cancer at the National Oncology Institute 2012–2015

| Type of care | Patients receiving care (%)* | Total cost (US$) | Mean cost per patient (US$) | 95% CI |

| Overall | 524/611 (85.8) | 2 231 728 | 4259 | (3915 to 4603) |

| Hospital admission | 449/611 (73.5) | 1 156 460† | 2576† | (2359 to 2792) |

| Radiotherapy | 110/611 (18.0) | 206 872 | 1881 | (1729 to 2033) |

| Chemotherapy | 406/611 (66.4) | 652 370 | 1607 | (1363 to 1851) |

| Surgery | 185/611 (30.3) | 216 026 | 1168 | (1077 to 1259) |

*Since a single patient could receive different types of care, calculations were made separately for each category and percentages do not add up to 100%.

†Calculated for occupied bed-days.

US$, US dollars.

bmjopen-2017-017266supp002.pdf (95.3KB, pdf)

Table 4 presents the costs stratified by sex, social security status and disease stage groups, according to type of care received. Women had an OMC per patient of US$4258, while for men it was US$4260. For those with social security, the OMC per patient was US$4414, whereas for those without social security, it was US$3657. Patients with stage I-III disease presented an OMC of US$5174, compared with US$4930 for those with stage IV disease (see online supplementary figure 2 for detailed cost distributions). No statistically significant differences were observed in the OMC between groups.

Table 4.

Direct cost estimates by sex, social security status and clinical stage of patients with gastric cancer according to type of care received at the National Oncology Institute 2012–2015

| Type of care | Male patients n=380 | Female patients n=231 | Bootstrap p Value | ||||

| Received care (%)* | Mean cost (US$) | 95% CI | Received care (%)* | Mean cost (US$) | 95% CI | ||

| O | 324/380 (85.3) | 4260 | (3789 to 4731) | 200/231 (86.6) | 4258 | (3774 to 4741) | 0.994 |

| HA | 281/380 (73.9) | 2487† | (2219 to 2755) | 168/231 (72.7) | 2724† | (2340 to 3108) | |

| CT | 247/380 (65.0) | 1694 | (1257 to 2131) | 159/231 (68.8) | 1472 | (1204 to 1740) | |

| RT | 69/380 (18.2) | 1915 | (1695 to 2135) | 41/231 (17.7) | 1823 | (1582 to 2064) | |

| SR | 117/380 (30.8) | 1118 | (1028 to 1209) | 68/231 (29.4) | 1253 | (1074 to 1432) | |

| Patients with social security n=473 | Patients without social security n=138 | ||||||

| O | 417/473 (88.2) | 4414 | (4014 to 4813) | 107/138 (77.5) | 3657 | (3014 to 4299) | 0.059 |

| HA | 357/473 (75.5) | 2562† | (2318 to 2806) | 92/138 (66.7) | 2628† | (2111 to 3145) | |

| CT | 326/473 (68.9) | 1722 | (1376 to 2069) | 80/138 (58.0) | 1136 | (833 to 1439) | |

| RT | 93/473 (19.7) | 1848 | (1665 to 2031) | 17/138 (12.3) | 2060 | (1702 to 2417) | |

| SR | 160/473 (33.8) | 1202 | (1103 to 1302) | 25/138 (18.1) | 945 | (871 to 1019) | |

| Stage I–III n=111 | Stage IV n=212 | ||||||

| O | 108/111 (97.3) | 5174 | (4516 to 5832) | 201/212 (94.8) | 4930 | (4330 to 5529) | 0.598 |

| HA | 86/111 (77.5) | 2994† | (2353 to 3635) | 179/212 (84.4) | 2853† | (2484 to 3221) | |

| CT | 85/111 (76.6) | 890 | (683 to 1097) | 173/212 (81.6) | 2055 | (1579 to 2530) | |

| RT | 60/111 (54.1) | 2341 | (2243 to 2440) | 27/212 (12.7) | 1297 | (897 to 1697) | |

| SR | 85/111 (76.6) | 1003 | (930 to 1075) | 69/212 (32.5) | 1302 | (1127 to 1477) | |

*Since a single patient could receive different types of care, calculations were made separately for each category and percentages do not add up to 100%.

†Calculated for occupied bed-days.

CT, chemotherapy; HA, hospital admission; O, overall; RT, radiotherapy; SR, surgery; US$, US dollars.

bmjopen-2017-017266supp003.pdf (100.9KB, pdf)

Discussion

Our findings suggest that lack of social security, a poorly differentiated tumour, clinical stage IV and overlapping anatomic location were associated with an increased risk of dying, independently of other socioeconomic and clinical variables. Furthermore, the overall 1-year survival rate in our study was 41% and the estimated OMC of GC care per patient was US$4259.

Socioeconomic factors such as insurance coverage and geographic location have been implicated in survival outcomes and healthcare disparities.18–22 Likewise, cultural differences have been documented as strong factors influencing medical care in many Latin American countries, especially in cancer.21 23 According to national estimates, 80% of the Panamanian population has social security, of which 57% are active workers and 43% are beneficiaries.24 In our results, patients without social security had a twofold higher risk of dying in comparison to those with social security. Similarly, in Colombia, patients with a more affluent socioeconomic status and a private health insurance regimen had a significantly higher GC survival.25 The lack of social security has been related to late-stage diagnosis,26 and health insurance regimes facilitate greater access to physician care and increase medical service use, thus granting patients longer survival times.27 In addition, reports on other types of cancer in Panama have identified lack of social security as a barrier in access to healthcare.4 5 Likewise, a previous study conducted in Sweden has shown the importance of socioeconomic factors in GC survival, where a higher educational level was associated with a higher survival and patients living in rural areas had a higher risk of dying due to this type of cancer.28 Of note, one-third of our patients were unemployed, most of them being older than 65 years and beneficiaries from the social security system. The higher proportion of unemployed patients observed, compared with another study of GC in the region,29 highlights the importance of social security as an aid in front of the complex socioeconomic situation of this population, heavily dependent on having a formally employed relative to have better access to GC-related services. Taken together, these findings emphasise the importance of socioeconomic determinants in the disease outcomes of GC.

Geographic disparities in Panama are a well-known problem, as for some indigenous and other remote regions, human resources and equipment available for diagnosis and treatment are limited.30 Together, Panama and Colon comprise more than half of the national population and have higher access to healthcare services, one of them being host to the NOI.31 Herrera was the province with most patients treated at the NOI per 100 000 population, which could be explained by the fact of having the country’s highest number of health professionals per capita,31 giving the patients higher chances of being diagnosed and referred to the NOI. Nevertheless, with half of the amount of health professionals per capita, Veraguas province was second in patients treated at the NOI per 100 000 population, and according to national estimates it ranks first in incidence and second in mortality in the country.32 Interestingly, the provinces of Veraguas and Cocle, despite having the highest proportion of their patients with stage IV disease (74.1% and 69.6%, respectively), accounted for two of the smallest proportions of their residents being diagnosed in institutions inside their territory (10.9% and 7.4%, respectively). Although geography was not associated with a higher risk of dying in our study, these findings underscore the need of further research on GC to determine geographical disparities in depth, as well as lifestyle, environmental, genetic factors and the interaction among them.33–36

In agreement with other studies,12 37 the male to female ratio was 1.64 and GC was most common in the elderly.12 38 Nevertheless, we found a high proportion of EOGC (14.7%) compared with those reported in most countries of the region,38 only surpassed by Guatemala in Central America with national estimates of 16.5%,12 a comparison worth noting even if our results are based on a single institution. Likewise, in a hospital-based study conducted in Mexico, a similar proportion of EOGC was reported.39 These discrepancies might mirror differences in under-reporting, environmental risk factors (other infections, exposure to chemicals, alcohol consumption), genetic susceptibility and information-seeking patterns, making it difficult to compare.

Clinical stage was only reported in half of the patients, a fivefold lower rate than that reported by the SEER8 and twice as low as the one reported in a community in Chile.40 Moreover, two-thirds had stage IV disease, compared with 25% and 60%, as reported in other studies from developed and developing countries.40 41 It is widely known that being initially diagnosed at an advanced clinical stage of the disease correlates with delayed diagnosis.42 Given that up to 50% of GC patients have unspecific gastrointestinal symptoms,43 and alarm symptoms are usually present at advanced stage in most cases,44 45 early diagnosis is a challenge. Remarkably, 14.2% of the patients in our study were diagnosed and then lost to follow-up for receiving any type of care, compared with other studies that have shown higher compliance rates to appointments or treatment.46 These patients were mostly male, 75 years or older, had social security coverage (this includes beneficiaries), were unemployed, were married or in a common-law marriage, belonged to the group of provinces of Panama and Colon and were described as being Mestizo. It is well known that socioeconomic disparities negatively influence access to endoscopic services causing delayed diagnoses,47 48 access to further appointments and inadequate adherence to treatment49 and might have hampered the successful staging and follow-up of patients.

Non-cardia tumours were three times as frequent as cardia tumours, and intestinal type tumours were predominant versus diffuse-type tumours, a consistent finding in the region.12 38 However, poorly differentiated tumours were twice as common in comparison to the well/moderately differentiated group. Despite the histological paradigm stating that intestinal type tumours are well differentiated and that diffuse type tumours are poorly differentiated,50 51 other studies have reported similar results.52 53 Yet, a possible explanation for this discordance is the high under-reporting of the histological type variable versus the almost complete reporting of the tumour grade variable.

The 1-year survival rate was 41%, higher than those from other studies of the region (32%) but lower in comparison to developed countries (57%).8 25 Other studies have shown that unfavourable clinical and histological features (advanced clinical stage, diffuse type, overlapping and poorly differentiated tumours) are poor prognostic factors for GC survival.40 54 Nevertheless, our survival estimates should be interpreted with caution, given that our study only included patients attending the NOI. National studies are needed to determine the true GC rates of the whole Panamanian population.

Published data regarding costs of cancer care are limited in Latin America. A recent study conducted in Chile, evaluating direct and indirect costs of cancer (expressed as 2012 US$), reported that GC accounted for the highest direct costs among all cancers.18 In a report published by the Panamanian Ministry of Health in 2010, GC was responsible for the fourth highest cost among all cancers in Panama.30 A similar finding was seen in a population-based study conducted in the USA, in which costs of care for 18 different tumour sites were calculated using SEER and Medicare claims data from 1999 to 2003 (expressed as 2004 US$).55

The OMC of care per patient in our study was US$4259 compared with the Chilean study that reported an OMC per patient of 3 706 145 Chilean pesos (CLP) (approximately US$7642) for public health insurance regimes and 3 102 978 CLP (approximately US$6398) for private health insurance regimes.18 The study conducted in the USA reported these costs by phases of care, reaching mean net costs as high as US$46 501 in the initial phase (first 12 months after diagnosis) and US$54 947 during the last year of life. On the other hand, in a 2015 cross-sectional study from Iran, the mean cost per patient was US$2596.56 Differences in OMC between studies might be explained by distinct definitions of types of care, since costs for a different range of services were included in each report.

Hospital admission accounted for the highest proportion of the total costs of care (51.8%), as reported previously.55 Given the introduction of newer, costly chemotherapeutic agents in the latest years and that a majority of patients in our study was reported with stage IV disease, one would expect chemotherapy to be accountable for the highest proportion of costs.57 Nevertheless, underestimation of chemotherapy costs is likely, since we only included costs for medications and were not able to include other additional expenses related to chemotherapy sessions. Supporting this, according to previous local estimates, chemotherapy represented the highest institutional expenditure at the NOI in 2009.30

Women tend to have higher health resource use and expenditures than men.58 This pattern, however, has not been reported for most tumour sites55 and was neither seen in our study. When assessing costs by tumour stage, some cancers may reflect higher costs with more advanced stages, but for cancers that are usually diagnosed in an advanced stage and with relatively short survival times as GC, differences in costs by stage are slighter,55 as observed in our results. The greatest gap in OMC was observed when comparing social security status groups, with no statistically significant differences found. Even if offered the same standard of care, patients without social security accounted for a lower expenditure (US$3657) compared with those with social security (US$4414). In fact, in our study, patients without social security comprised only 20.4% of the patients receiving care versus 79.6% patients who had social security. These disparities highlight the possibility that lack of social security and thus high out-of-pocket expenses are important barriers in seeking care, resulting in lower healthcare use and therefore reflecting lower institutional expenditure in GC patients without social security.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study assessing baseline characteristics of patients with GC and costs related to its care in Panama. A key strength of this study was that mortality data were ascertained with the NMR. The use of actual chemotherapeutic doses administered allowed a more accurate calculation of medication costs, and using the bootstrap method for mean cost comparison purposes provided us with a more flexible tool to compare arithmetic mean costs, avoiding the assumptions and limitations inherent to other methods.59–61

Several limitations deserve mention. This study encompassed patients from a single cancer institution and our results cannot be extrapolated to the whole population. However, the NOI is the biggest and main cancer referral public hospital in the country, where the majority of the cancer patients from all over the country are treated.4 5 There was a considerable amount of under-reporting and missing variables (eg, Helicobacter pylori infection status, genetic factors), which have demonstrated to have a central role in disease outcomes. Lastly, incomplete data regarding chemotherapy protocol sessions, resource use and outpatient expenses, most likely led to underestimation of costs.

In conclusion, socioeconomic disparities strongly influence GC outcomes and healthcare use. Our results suggest the need for an in-depth characterisation of the barriers in access to GC-related services, particularly for diagnosis and to address geographical disparities, such as the one observed in the Veraguas province.

Given that efforts directed towards making earlier diagnoses have proven to reduce the gap in cancer survival between different socioeconomic groups,62 health policies should move towards a more inclusive system for GC patients from lower socioeconomic strata. Further, building capacity training, boosting the investment in medical equipment and improving databases to have more accurate estimates of GC data in our population are strongly encouraged, including social security status in future studies evaluating cancer mortality in Panama.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Fulvia Ibarra from the National Institute of Census and Statistics, Cecilio Niño from the Gorgas Memorial Institute for Health Studies, José Jiménez, head of the Department of Clinical Files at the NOI, Erick Trejos, head of the Department of Finance at the NOI and Dr Reina Roa, Director of National Planning at the Ministry of Health of Panama.

Footnotes

Contributors: FC and DS curated the data. FC, DS and IMV analysed the data and wrote the draft of the work. FC, DS, MT, IMV, MTC, VH, MC, BG and JM interpreted the data, did the research and critically revised the draft for important intellectual content. BG and JM designed and supervised the work. Final approval of the version to be published was given by FC, DS, MT, IMV, MTC, VH, BG, MC and JM. All the authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: FC, DS, MT, IMV, VH, BG, MC, JM have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare no conflicts of interest. MTC reports medical managing at Sanofi Pasteur, outside the submitted work.

Ethics approval: Gorgas Memorial Institute Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1. Bonequi P, Meneses-González F, Correa P, et al. Risk factors for gastric cancer in Latin America: a meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control 2013;24:217–31. 10.1007/s10552-012-0110-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Registro Nacional de Cáncer (National Cancer Registry). El cáncer en Panama. Año 2011. http://190.34.154.93/rncp/sites/all/files/rncp_2011_monografiadocx.pdf (accessed 2 Oct 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mahar AL, El-Sedfy A, Brar SS, et al. Are we lacking economic evaluations in gastric cancer treatment? Pharmacoeconomics 2015;33:83–7. 10.1007/s40273-014-0215-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roquebert M, Palacios G, Ramos Y, et al. Barreras y oportunidades en la atención de salud en mujeres con cáncer de mama de la ciudad de Panamá. Año 2012 2012. http://ww5.komen.org/uploadedFiles/Content/AboutUs/GlobalReach/Panama%20Health%20System%20Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roquebert M, Ramos Y, Palacios G, et al. Estudio cualitativo, descriptivo para investigar barreras y oportunidades en la atención de salud de cáncer de mama en mujeres de las provincias de Chiriquí, Herrera, Los Santos, Veraguas y en mujeres indígenas de Panamá. Año 2014 2014. http://ww5.komen.org/uploadedFiles/_Komen/Content/Grants_Central/International_Grants/Grantee_Resources/HSR_Panama_2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mikkelsen L, Phillips DE, AbouZahr C, et al. A global assessment of civil registration and vital statistics systems: monitoring data quality and progress. Lancet 2015;386:1395–406. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60171-4 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60171-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Milne AN, Offerhaus GJ. Early-onset gastric cancer: learning lessons from the young. World J Gastrointest Oncol 2010;2:59–64. 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i2.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. National Cancer Institute. SEER stat fact sheets: stomach cancer, 2015. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/stomach.html

- 9. Social Security Administration. Social security programs throughout the World: the Americas, 2015. https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/progdesc/ssptw/2014-2015/americas/panama.html (accessed 31 Jan 17).

- 10. International Labour Office. Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A statistical picture Geneva, Switzerland second edition, 2013. http://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/-dgreports/-stat/documents/publication/wcms_234413.pdf (accessed 20 Mar 2017).

- 11. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censo. Estimación del producto interno bruto provincial, según categoría de actividad económica, a precios de 1996. Años2006 2003;05 https://www.contraloria.gob.pa/inec/publicaciones/Publicaciones.aspx?ID_SUBCATEGORIA=26&ID_PUBLICACION=63&ID_IDIOMA=1&ID_CATEGORIA=4 [Google Scholar]

- 12. Corral JE, Delgado Hurtado JJ, Domínguez RL, et al. The descriptive epidemiology of gastric cancer in Central America and comparison with United States Hispanic populations. J Gastrointest Cancer 2015;46:21–8. 10.1007/s12029-014-9672-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification . Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1965;64:31–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zheng HC, Li XH, Hara T, et al. Mixed-type gastric carcinomas exhibit more aggressive features and indicate the histogenesis of carcinomas. Virchows Arch 2008;452:525–34. 10.1007/s00428-007-0572-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kim SH, Ha TK, Kwon SJ. Evaluation of the 7th AJCC TNM staging system in point of ymph ode lassification. J Gastric Cancer 2011;11:94–100. 10.5230/jgc.2011.11.2.94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censo. Panamá en cifras, 2014. https://www.contraloria.gob.pa/inec/Publicaciones/Publicaciones.aspx?ID_SUBCATEGORIA=45&ID_PUBLICACION=699&ID_IDIOMA=1&ID_CATEGORIA=17 (accessed 19 May 2016).

- 17. Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the bootstrap (Chapman & Hall/CRC monographs on statistics & applied probability): Chapman and Hall/CRC, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cid C, Herrera C, Rodríguez R, et al. (Assessing the economic impact of cancer in Chile: a direct and indirect cost measurement based on 2009 registries). Medwave 2016;16:e6509 10.5867/medwave.2016.07.6509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pereira L, Zamudio R, Soares-Souza G, et al. Socioeconomic and nutritional factors account for the association of gastric cancer with Amerindian ancestry in a Latin American admixed population. PLoS One 2012;7:e41200 10.1371/journal.pone.0041200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shavers VL, Brown ML. Racial and ethnic disparities in the receipt of cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst 2002;94:334–57. 10.1093/jnci/94.5.334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Strasser-Weippl K, Chavarri-Guerra Y, Villarreal-Garza C, et al. Progress and remaining challenges for cancer control in Latin America and the Caribbean. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1405–38. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00218-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin 2004;54:78–93. 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kagawa-Singer M, Valdez Dadia A, Mc Y, et al. Cancer, Culture, and Health Disparities: Time to chart a new course? CA: a cancer journal for clinicians . 2010;60:12–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Social Security Fund. Social security coverage in Panama. 2010. http://www.css.gob.pa/seguridadsocial/cobertura.html (accessed 14 Feb 2017).

- 25. Bravo LE, García LS, Collazos PA. Cancer survival in Cali, Colombia: A population-based study, 1995-2004. Colomb Med 2014;45:110–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roetzheim RG, Pal N, Tennant C, et al. Effects of health insurance and race on early detection of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999;91:1409–15. 10.1093/jnci/91.16.1409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kang S, Kwon YD, You CH, et al. The benefits of supplementary private health insurance for healthcare utilization and survival among stomach cancer patients. Tohoku J Exp Med 2009;217:243–50. 10.1620/tjem.217.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ljung R, Drefahl S, Andersson G, et al. Socio-demographic and geographical factors in esophageal and gastric cancer mortality in Sweden. PLoS One 2013;8:e62067 10.1371/journal.pone.0062067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. de Boer AG, Bruinvels DJ, Tytgat KM, et al. Employment status and work-related problems of gastrointestinal cancer patients at diagnosis: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000190 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ministerio de Salud de Panamá (Panamanian Ministry of Health). Plan Nacional para la Prevención y Control del Cáncer (National Plan for Prevention and Control of Cancer) 2010 - 2015, 2011. http://190.34.154.93/rncp/sites/all/files/pnpcc_0.pdf

- 31. National Institute of Statistics and Census. Panama in numbers: years 2010-2014, 2014. https://www.contraloria.gob.pa/inec/Publicaciones/Publicaciones.aspx?ID_SUBCATEGORIA=45&ID_PUBLICACION=699&ID_IDIOMA=1&ID_CATEGORIA=17

- 32. Gorgas Memorial Institute for Health Studies. Geographic information system of cancer mortality and incidence in Panama. Panama 2000-2013. http://www.gorgas.gob.pa/SIGCANCER/Inicio.htm

- 33. Lee YY, Derakhshan MH. Environmental and lifestyle risk factors of gastric cancer. Arch Iran Med 2013;16:358-65 doi:013166/AIM.0010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McLean MH, El-Omar EM. Genetics of gastric cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;11:664–74. 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yamaoka Y, Kato M, Asaka M. Geographic differences in gastric cancer incidence can be explained by differences between helicobacter pylori strains. Intern Med 2008;47:1077–83. 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.0975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yuan W, Yang N, Li X. Advances in understanding how heavy metal pollution triggers gastric cancer. Biomed Res Int 2016;2016:1–10. 10.1155/2016/7825432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roder DM. The epidemiology of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer 2002;(Suppl 1):5–11. 10.1007/s10120-002-0203-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Sierra MS, Cueva P, Bravo LE, et al. Stomach cancer burden in central and South America. Cancer Epidemiol 2016. 44 (Suppl 1):S62–73. 10.1016/j.canep.2016.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ramos-De la Medina A, Salgado-Nesme N, Torres-Villalobos G, et al. Clinicopathologic characteristics of gastric cancer in a young patient population. J Gastrointest Surg 2004;8:240–4. 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Heise K, Bertran E, Andia ME, et al. Incidence and survival of stomach cancer in a high-risk population of chile. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:1854–62. 10.3748/wjg.15.1854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hundahl SA, Phillips JL, Menck HR. The National cancer data base report on poor survival of U.S. gastric carcinoma patients treated with gastrectomy. Fifth edition american joint committee on cancer staging, proximal disease, and the “different disease” hypothesis. Cancer2000: 88:921–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rossi S, Cinini C, Di Pietro C, et al. Diagnostic delay in breast cancer: correlation with disease stage and prognosis. Tumori 1990;76:559–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dicken BJ, Bigam DL, Cass C, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma: review and considerations for future directions. Ann Surg 2005;241:27–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Breslin NP, Thomson AB, Bailey RJ, et al. Gastric cancer and other endoscopic diagnoses in patients with benign dyspepsia. Gut 2000;46:93–7. 10.1136/gut.46.1.93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Meineche-Schmidt V, Jørgensen T ‘Alarm symptoms’ in patients with dyspepsia: a three-year prospective study from general practice. Scand J Gastroenterol 2002;37:999–1007. 10.1080/003655202320378167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hallissey MT, Allum WH, Jewkes AJ, et al. Early detection of gastric cancer. BMJ 1990;301:513–5. 10.1136/bmj.301.6751.513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kim NY, Oh JS, Choi Y, et al. Relationship between socioeconomic status and accessibility for endoscopic resection among gastric cancer patients: using National Health Insurance Cohort in Korea: poverty and endoscopic resection. Gastric Cancer 2017;20:61–9. 10.1007/s10120-016-0597-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lee H-Y, Park E-C, Jun JK, et al. Trends in socioeconomic disparities in organized and opportunistic gastric cancer screening in Korea (2005-2009). Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:1919–26. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Formenti SC, Meyerowitz BE, Ell K, et al. Inadequate adherence to radiotherapy in Latina immigrants with carcinoma of the cervix. Potential impact on disease free survival. Cancer 1995;75:1135–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kelley JR, Duggan JM. Gastric cancer epidemiology and risk factors. J Clin Epidemiol 2003;56:1–9. 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00534-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shah MA, Khanin R, Tang L, et al. Molecular classification of gastric cancer: a new paradigm. Clin Cancer Res 2011;17:2693–701. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shibata A, Longacre TA, Puligandla B, et al. Histological classification of gastric adenocarcinoma for epidemiological research: concordance between pathologists. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2001;10:75–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yuasa Y. Control of gut differentiation and intestinal-type gastric carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 2003;3:592–600. 10.1038/nrc1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yang D, Hendifar A, Lenz C, et al. Survival of metastatic gastric cancer: significance of age, sex and race/ethnicity. J Gastrointest Oncol 2011;2:77–84. 10.3978/j.issn.2078-6891.2010.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yabroff KR, Lamont EB, Mariotto A, et al. Cost of care for elderly cancer patients in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:630–41. 10.1093/jnci/djn103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Izadi A, Sirizi MJ, Esmaeelpour S, et al. Evaluating direct costs of gastric cancer treatment in Iran - case study in Kerman city in 2015. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2016;17:3007–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gómez B, Gordón C, Herrera V, et al. Gasto, Acceso y disponibilidad de los medicamentos en Panamá, 2007-2012: documento diagnóstico (Expenditure, access and availability of medications in Panama, 2007-2012: diagnostic report). 2014. http://siproy.mef.gob.pa/tab/15817_2010_24212_InformeMedicamentos.pdf (accessed 10 Feb 2017).

- 58. Owens GM. Gender differences in health care expenditures, resource utilization, and quality of care. J Manag Care Pharm 2008;14:2–6. 10.18553/jmcp.2008.14.S3-A.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Barber JA, Thompson SG. Analysis of cost data in randomized trials: an application of the non-parametric bootstrap. Stat Med 2000;19:3219–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mani K, Björck M, Lundkvist J, et al. Similar cost for elective open and endovascular AAA repair in a population-based setting. J Endovasc Ther 2008;15:1–11. 10.1583/07-2258.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Mani K, Lundkvist J, Holmberg L, et al. Challenges in analysis and interpretation of cost data in vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg 2010;51:148–54. 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.08.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Li R, Daniel R, Rachet B. How much do tumor stage and treatment explain socioeconomic inequalities in breast cancer survival? Applying causal mediation analysis to population-based data. Eur J Epidemiol 2016;31:603–11. 10.1007/s10654-016-0155-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017266supp001.pdf (123.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017266supp002.pdf (95.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2017-017266supp003.pdf (100.9KB, pdf)