Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to elucidate the impact of nutritional status on survival per Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score and Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) in patients with hypertension over 80 years of age.

Design

Prospective follow-up study.

Participants

A total of 336 hypertensive patients over 80 years old were included in this study.

Outcome measures

All-cause deaths were recorded as Kaplan-Meier curves to evaluate the association between CONUT and all-cause mortality at follow-up. Cox regression models were used to investigate the prognostic value of CONUT and GNRI for all-cause mortality in the 90-day period after admission.

Results

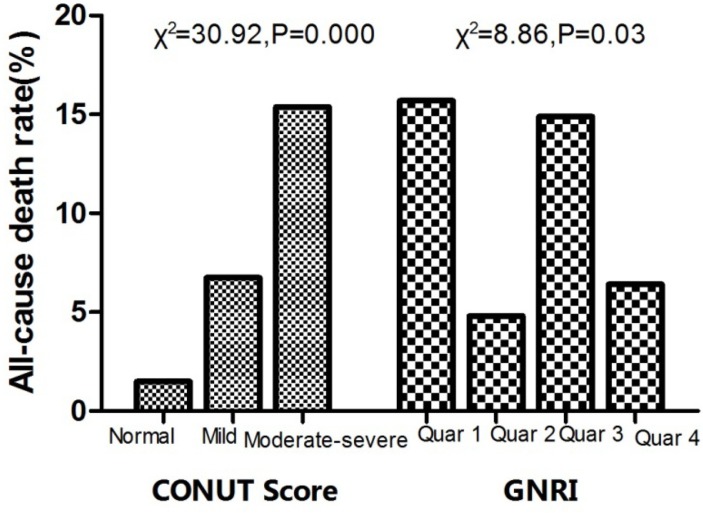

Hypertensive patients with higher CONUT scores exhibited higher mortality within 90 days after admission (1.49%, 6.74%, 15.38%, respectively, χ2=30.92, p=0.000). Surviving patients had higher body mass index (24.25±3.05 vs 24.25±3.05, p=0.012), haemoglobin (123.78±17.05 vs 115.07±20.42, p=0.040) and albumin levels, as well as lower fasting blood glucose (6.90±2.48 vs 8.24±3.51, p=0.010). Higher GRNI score (99.42±6.55 vs 95.69±7.77, p=0.002) and lower CONUT (3.13±1.98 vs 5.14±2.32) both indicated better nutritional status. Kaplan-Meier curves indicated that survival rates were significantly worse in the high-CONUT group compared with the low-CONUT group (χ1 =13.372, p=0.001). Cox regression indicated an increase in HR with increasing CONUT risk (from normal to moderate to severe). HRs (95% CI) for 3-month mortality was 1.458 (95% CI 1.102 to 1.911). In both respiratory tract infection and ‘other reason’ groups, only CONUT was a sufficiently predictor for all-cause mortality (HR=1.284, 95% CI 1.013 to 1.740, p=0.020 and HR=1.841, 95% CI 1.117 to 4.518, p=0.011). Receiver operating characteristic showed that CONUT higher than 3.0 was found to predict all-cause mortality with a sensitivity of 77.8% and a specificity of 64.7% (area under the curve=0.778, p<0.001).

Conclusion

Nutritional status assessed via CONUT is an accurate predictor of all-cause mortality 90 days postadmission. Evaluation of nutritional status may provide additional prognostic information in hypertensive patients.

Keywords: nutritional status, count, hypertension, all-cause mortality

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This was a study including 336 hypertensive patients over 80 years combined with diagnosed cardiovascular disease.

It is the first study to explore the relationship between the nutritional status based on Controlling Nutritional Status or Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index on admission and all-cause death in such very elderly hypertensive patients.

This study was a single-centre study that included a relatively small number of patients.

Follow-up studies were performed for only 90 days.

Introduction

The nutritional status of patients has drawn increased attention in a variety of clinical settings. There is a wealth of evidence to suggest that nutritional and immunologic status on admission is closely associated with the outcome of patients with cardiovascular disease.1–3 For elderly patients, the role of nutritional status is all the more important. Studies have shown that elderly patients with high nutritional risks are more likely to stay longer in the hospital than those without such risks.4 Nutritional risk has also been identified as an independent predictor of functional status and mortality among institutionalised elderly patients.5

Body mass index (BMI), serum albumin (Alb) level and prealbumin (PA) levels are the most commonly used indexes for evaluating nutritional status clinically. However, these single indexes exhibit limited clinical applications. Researchers have established improved nutritional indexes with an increasing number of complex nutritional indicators. The Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index (GNRI) is one of the most commonly used nutritional indicators in the elderly patient population.6 The Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score, which is calculated based on the serum Alb concentration, total peripheral lymphocyte count and total cholesterol (TC) concentration, was developed as a screening tool for early detection of poor nutritional status.7 Both indexes provide useful information for evaluating nutritional status comprehensively and are currently widely applied in the evaluation of patients with tumours8 who are undergoing dialysis.9 These tools exhibit limited application in cardiovascular disease, however.

Hypertension, the most commonly occurring disease in the elderly population, is associated with a number of comorbidities. When elderly patients are hospitalised due to infection or other reasons, the effects of nutritional status on their prognosis of merits further evaluation. The applicability of indexes such as GNRI or CONUT scores in assessing such patients has yet to be fully validated. The primary goal of this study was to elucidate the effect of nutritional status on survival in patients with hypertension and aged over 80 years.

Methods

Study design

This is a single centre, prospective, randomised, control and observational trial. We designed to consecutively enrol hypertensive patients hospitalised in a prescribed time and followed up to 90 days. The relationship between nutritional status and prognosis was analysed.

Patients

This study included patients with hypertension who were diagnosed using the criteria listed in Chinese Hypertension Prevention Guide (2010),10 hospitalised from January 2011 to December 2013 and aged >80 years. The study cohort comprised 336 Chinese hypertensive patients aged ≥80 years who were enrolled consecutively at the Department of Geriatric Cardiology. All the patients are veterans. The study was conducted at the People’s Liberation Army General Hospital under the full ethical approval of the Human Investigation Committee. Informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to their participation. The Chinese People’s Liberation Army General Hospital was their designated hospital and held their integrated long-term medical and final death records, which made it easier for us to follow them up effectively and judge endpoints accurately.

Follow-up

A follow-up on all selected subjects was conducted throughout a 90-day postadmission period. Follow-up times were set to occur 7, 14, 30 and 90 days after admission and were conducted by interviewing each patient via telephone and by reviewing his or her medical records. All-cause mortality was determined at the end of the follow-up period. No patient dropped out during the study period. Follow-up data were tracked directly and telephoned to interviews. Death was ascertained from the death record, that is, a legal document including time, site and other necessary information.

General information and medical history

General information, including age, sex, lifestyle (smoking and drinking) and basic medical history, was collected. Patients were selected based on height, weight, resting heart rate, systolic blood pressure and diastolic blood pressure (DBP).

Nutritional metabolism and related biochemical indexes

On admission, routine blood tests were conducted for all enrolled patients in the Central Laboratory of our hospital. Detection indexes included white blood cells, lymphocytes, platelets, haemoglobin (Hgb), serum creatinine, Alb, TC, triglyceride, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, fasting blood glucose (FBS), blood urea nitrogen, uric acid, PA and electrolyte index.

The nutritional status of each patient was also evaluated using two composite indexes: CONUT score and GNRI. The CONUT score was determined in accordance with the tool described in table 1, which was first used by Ignacio de Ulíbarri et al.7 GNRI, which includes two nutritional indicators (Alb and actual weight compared with ideal body weight), was developed by modifying the nutritional risk index for elderly patients. GNRI=(1.487* serum Alb (g/L)) t(41.7 *present/usual weight (kg)).6

Table 1.

Screening tool for Controlling Nutritional Status

| Parameter | Requirements | Score |

| Albumin (g/L) | ≥35 | 0 |

| 30–34 | 2 | |

| 25–29 | 4 | |

| <25 | 6 | |

| Total lymphocyte count (/mL) | ≥1600 | 0 |

| 1200–1599 | 1 | |

| 800–1199 | 2 | |

| <800 | 3 | |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | ≥4.65 | 0 |

| 3.62–4.64 | 1 | |

| 2.58–3.61 | 2 | |

| <2.58 | 3 |

Dysnutritional states: normal 0–1; mild 2–4; moderate 5–8; severe 9–12.

Statistical analysis

All calculations were performed in SPSS V.22.0. For continuous quantitative data, the K-S normality test was first applied to analyse whether the normal distribution of quantitative data could be analysed by an independent-sample Student’s t-test. Data that were not normally distributed were analysed via Mann-Whitney U test. A Pearson’s χ2 test was run to analyse the categorical variables. Survival curves were generated via Kaplan-Meier method, and multivariate analysis using a Cox proportional hazards model was used for independent tests of significance. Two-tailed p values<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics

A total of 336 hypertensive patients were enrolled, including 323 males and 13 females, with an average age of 87.39±5.23 years. All patients were diagnosed with hypertension ranging from 5 to 27 years and had received antihypertensive drug treatment. All patients had a history of coronary artery disease (CAD); 83 patients had a history of myocardial infarction (MI), 29 patients had received stent therapy, 67 suffered from chronic heart failure (CHF), 167 had type 2 diabetes mellitus and 124 had anaemia. Of these cases, 192 were admitted for respiratory tract infection (RTI), and the remaining 144 patients were admitted for non-infective factors, such as angina pectoris or uncontrolled blood pressure, among others.

The CONUT scores of the selected patients were determined and analysis was conducted as presented in table 2. Only five patients scored over 9, which indicates severe malnutrition. We combined their data with those exhibiting moderate malnutrition for analysis. Heart rate and blood glucose levels were higher in patients with high CONUT scores than in those with low CONUT scores. The proportion of patients with poor nutritional status due to admission caused by RTI was significantly high as well (χ2 =70.835, p=0.000).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the study population and nutritional parameters based on nutritional status

| Normal (CONUT=0–1, n=67) |

Mild malnutrition (CONUT 2–4, n=178) |

Moderate–severe malnutrition (CONUT≥5, n=91) |

p | |

| Age (year, ±s) | 87.24±4.75 | 87.18±4.95 | 87.75±5.56 | 0.638 |

| Male (n, %) | 64 (95.52) | 169 (94.54) | 90 (98.90) | 0.270 |

| Smoking history (n, %) | 19 (28.36) | 60 (33.71) | 44 (48.35) | 0.018 |

| Anaemia (n, %) | 20 (29.85) | 63 (35.39) | 41 (45.05) | 0.129 |

| DM (n, %) | 37 (55.22) | 93 (52.24) | 34 (37.36) | 0.035 |

| Admission for RTI (n, %) | 18 (26.86) | 91 (51.12) | 83 (91.21) | 0.000 |

| SBP (mm Hg, ±s) | 129.49±15.11 | 133.96±18.88 | 134.04±19.92 | 0.236 |

| DBP (mm Hg, ±s) | 67.85±9.40 | 67.71±13.03 | 68.50±11.03 | 0.953 |

| HR (beat/min, ±s) | 70.97±12.94 | 73.22±14.61 | 82.20±17.46 | 0.000 |

| BMI (kg/m2, ±s) | 25.08±3.10 | 24.15±3.09 | 23.03±2.73 | 0.010 |

| Hgb (g/L, ±s) | 125.06±17.23 | 123.01±16.81 | 122.64±18.76 | 0.475 |

| TC (mmol/L, ±s) | 4.53±0.08 | 2.77±1.60 | 0.93±1.51 | 0.000 |

| TG (mmol/L, ±s) | 1.85±1.28 | 1.15±1.02 | 0.54±0.27 | 0.000 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L, ±s) | 2.63±0.61 | 1.76±0.72 | 1.53±0.71 | 0.000 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L, ±s) | 1.16±0.36 | 1.03±0.46 | 1.03±0.48 | 0.104 |

| sCr (mmol/L, ±s) | 106.66±44.72 | 109.24±53.41 | 110.03±59.36 | 0.941 |

| BUN (mmol/L, ±s) | 8.18±3.95 | 9.20±4.61 | 10.21±4.76 | 0.016 |

| UA (umol/L, ±s) | 335.51±101.25 | 347.15±97.37 | 321.76±109.13 | 0.081 |

| TP (g/L, ±s) | 69.40±5.25 | 68.75±6.36 | 65.90±7.56 | 0.000 |

| Albumin (g/L, ±s) | 40.13±3.31 | 39.49±3.50 | 35.83±4.73 | 0.000 |

| FBS (mmol/L, ±s) | 6.26±2.41 | 7.11±2.64 | 7.39±2.60 | 0.021 |

| Prealbumin (mg/dL, ±s) | 10.76±12.88 | 17.02±12.05 | 19.15±7.25 | 0.000 |

BMI, body mass index; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; FBS, fasting blood glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; Hgb, haemoglobin; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; RTI, respiratory tract infection; SBP, systolic blood pressure; sCr, serum creatinine; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride; TP, total protein; UA, uric acid.

Table 3 compares the nutritional index of patients with different reasons for admission. Patients with RTI showed generally low nutritional status, including low BMI, Alb level, GNRI score, high FBS and CONUT score on admission.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the study population and nutritional parameters by different admission reasons

| RTI (n=192) | Other causes (n=144) | Statistical value | p | |

| Age (year) | 87.56±5.29 | 87.25±5.11 | 0.292 | 0.589 |

| Male (n, %) | 185 (96.35%) | 143 (95.97%) | 0.033 | 0.855 |

| Smoking history (n, %) | 77 (40.1%) | 46 (30.87%) | 3.101 | 0.078 |

| DM (n, %) | 88 (45.83%) | 79 (53.02%) | 1.734 | 0.188 |

| Hyperlipidemia (n, %) | 98 (51.04%) | 79 (53.02%) | 0.132 | 0.717 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.68±3.16 | 24.53±3.00 | 4.991 | 0.026 |

| TP (g/L) | 67.79±7.65 | 68.08±5.67 | 0.150 | 0.699 |

| Alb (g/L) | 37.43±4.62 | 40.00±5.25 | 33.01 | 0.000 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 122.69±19.10 | 123.61±15.14 | 0.235 | 0.628 |

| Creatinine (umol/L) | 109.40±56.54 | 108.73±48.46 | 0.013 | 0.909 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 9.92±5.10 | 8.53±3.84 | 7.670 | 0.006 |

| FBS (mmol/L) | 7.63±2.75 | 6.19±2.14 | 27.98 | 0.000 |

| UA (mmol/L) | 328.74±102.06 | 350.96±104.49 | 3.875 | 0.050 |

| Prealbumin (mg/dL) | 18.73±8.89 | 13.58±13.65 | 17.645 | 0.000 |

| GRNI score | 97.72±7.68 | 100.49±5.35 | 11.822 | 0.001 |

| CONUT score | 4.19±2.08 | 2.09±1.34 | 112.593 | 0.000 |

Alb, albumin; BMI, body mass index; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CONUT, Controlling Nutritional Status; DM, diabetes mellitus; FBS, fasting blood glucose; GNRI, Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index; RTI, respiratory tract infection; TP, total protein; UA, uric acid.

Follow-up results

A total of 27 deaths were recorded in the 90-day follow-up; most of these deaths occurred between 30 and 90 days (n=17, 62.97%) postadmission. The parameters and characteristics of different outcomes for the patients are presented in table 4. No differences in age, sex or combination of diseases were found between different outcomes. Likewise, no differences in systolic blood pressure were found. The surviving patients, however, showed increased BMI (24.25±3.05 vs 24.25±3.05, p=0.012), Hgb (123.78±17.05 vs 115.07±20.42, p=0.040), and Alb level, as well as reduced DBP (62.48±9.60 vs 68.31±12.02, p=0.016) and FBS (6.90±2.48 vs 8.24±3.51, p=0.010). No significant difference in plasma PA level between different outcomes was indicated (19.21±8.70 vs 16.25±11.68, p=0.200).

Table 4.

Comparison of characteristics of study population and laboratory parameters by different outcomes

| Death for all cause (n=27) | Survival (n=314) | p | |

| Age (year) | 89.29±4.57 | 87.26±5.25 | 0.052 |

| Male (n, %) | 27 (100) | 308 (98.08) | 0.281 |

| DM (n, %) | 15 (55.56) | 152 (48.41) | 0.304 |

| Hyperlipidemia (n, %) | 12 (44.44) | 165 (52.55) | 0.431 |

| CKD (n, %) | 9 (33.33) | 88 (28.02) | 0.667 |

| Anaemia (n, %) | 13 (48.15) | 112 (35.67) | 0.206 |

| SBP (mm Hg) | 133.29±18.43 | 126.85±20.16 | 0.085 |

| DBP (mm Hg) | 68.31±12.02 | 62.48±9.60 | 0.016 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.31±3.31 | 24.25±3.05 | 0.012 |

| TP (g/L) | 67.85±9.59 | 67.92±6.58 | 0.962 |

| Alb (g/L) | 36.37±5.00 | 38.74±4.16 | 0.005 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) | 115.07±20.42 | 123.78±17.05 | 0.040 |

| Creatinine (umol/L) | 110.74±61.19 | 108.97±52.44 | 0.868 |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 10.86±4.64 | 9.18±4.62 | 0.071 |

| FBS (mmol/L) | 8.24±3.51 | (6.90±2.48 | 0.010 |

| UA (mmol/L) | 312.00±82.94 | 340.72±105.31 | 0.169 |

| Prealbumin (mg/dL) | 19.21±8.70 | 16.25±11.68 | 0.200 |

| CONUT score | 5.14±2.32 | 3.13±1.98 | 0.000 |

| GNRI | 95.69±7.77 | 99.42±6.55 | 0.026 |

Alb, albumin; BMI, body mass index; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CONUT, Controlling Nutritional Status; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DM, diabetes mellitus; FBS, fasting blood glucose; GNRI, Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TP, total protein; UA, uric acid

Surviving patients had improved GRNI scores (99.42±6.55 vs 95.69±7.77, p=0.002) and reduced CONUT scores (3.13±1.98 vs 5.14±2.32) in the follow-up period, both of which indicated improved nutritional status. We found that, along with increase in CONUT score, which suggests worse malnutrition, the incidence of all-cause mortality increased. This tendency was not observed in the GRNI group, however, as illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1.

All-cause mortality among different nutritional statuses. CONUT, Controlling Nutritional Status; GNRI, Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index.

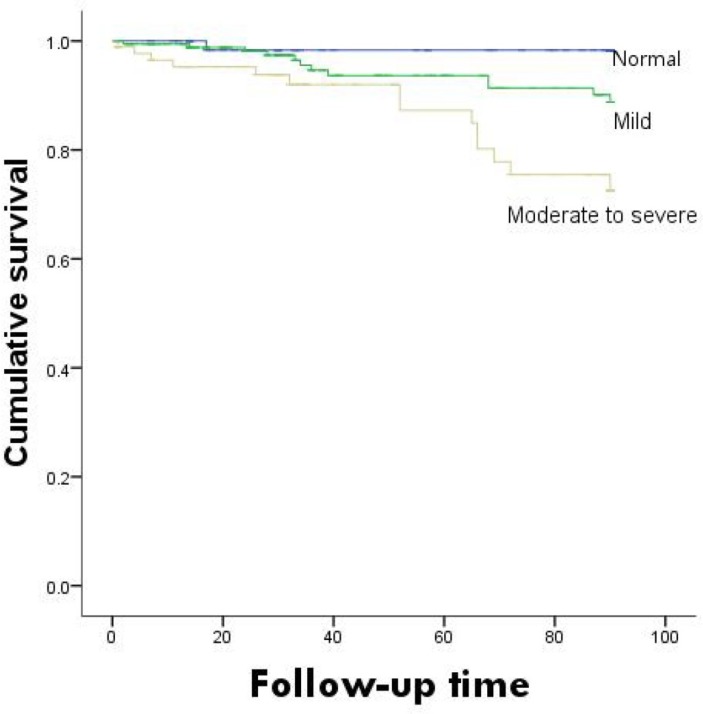

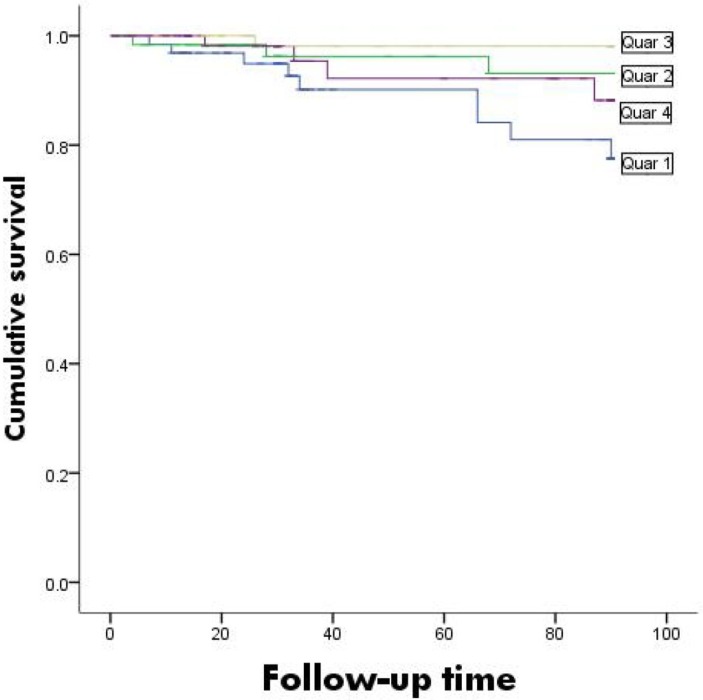

Survival analysis according to CONUT and GNRI

Survival curves based on different nutritional evaluations were plotted as shown in figure 2. The survival rates were significantly lower in the high-CONUT group than in the low-CONUT group (χ2 =13.372, p=0.001). The survival curves based on the GNRI are shown in figure 3. Differences among groups could not be determined (χ2 =7.694, p=0.053).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Controlling Nutritional Status.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index.

Prognostic values of CONUT and GNRI

Multivariate Cox regression analyses were conducted to investigate the possible predictors of all-cause mortality in the study population (table 5). By regression, both RTI and CONUT were independent predictors of 3-month all-cause mortality. Increasing HRs were observed with increasing CONUT risk (from normal to moderate to severe). The HRs (95% CI) for the 90-day mortality were 1.458 (95% CI 1.102 to 1.911, p=0.015). No significant correlation was indicated between the GNRI participants (HR=1.038, 95% CI 0.960 to 1.115, p=0.313).

Table 5.

Multivariate Cox regression for all-cause mortality

| B | Wald | Sig | HR | 95% CI | |

| RTI | 0.436 | 4.915 | 0.018 | 1.461 | 1.109 to 2.791 |

| Chronic heart failure | 0.037 | 1.829 | 0.052 | 1.008 | 0.873 to 1.059 |

| Age | 1.691 | 1.016 | 0.098 | 1.023 | 0.731 to 1.078 |

| BMI | −0.148 | 2.180 | 0.140 | 1.102 | 0.831 to 1.213 |

| Prealbumin | 0.025 | 0.675 | 0.411 | 1.026 | 0.965 to 1.090 |

| GNRI | 0.037 | 1.019 | 0.313 | 1.038 | 0.916 to 1.115 |

| CONUT | 0.359 | 5.926 | 0.015 | 1.458 | 1.012 to 1.911 |

BMI, body mass index; CONUT, Controlling Nutritional Status; GNRI, Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index; RTI, respiratory tract infection.

Given that RTI is an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality, we further conducted Cox regression according to different reasons for admission as shown in table 6. In the non-infection group, CONUT independently predicted all-cause mortality in the patients. However, in the RTI group, only CONUT was identified as an accurate predictor of all-cause mortality (HR=1.284, 95% CI 1.013 to 1.740, p=0.020); age also was link to all-cause mortality (HR=1.139, 95% CI 1.007 to 1.287, p=0.038).

Table 6.

Cox regression analysis of common nutritional evaluation index for possible predictors of all-cause mortality by reason of admission

| Adjusted HR with 95% CI for RTI | Adjusted HR with 95% CI for other reasons | |||||

| HR | 95% CI | p | HR | 95% CI | p | |

| Age | 1.139 | 1.007 to 1.287 | 0.038 | 1.254 | 0.873 to 2.497 | 0.986 |

| BMI | 0.837 | 0.676 to 1.035 | 0.101 | 0.817 | 0.364 to 1.007 | 0.748 |

| Prealbumin | 1.022 | 0.948 to 1.102 | 0.573 | 2.418 | 0.014 to 42.28 | 0.633 |

| GNRI | 1.057 | 0.978 to 1.143 | 0.159 | 1.231 | 0.816 to 4.941 | 0.747 |

| CONUT | 1.284 | 1.013 to 1.740 | 0.020 | 1.841 | 1.117 to 4.518 | 0.011 |

BMI, body mass index; CONUT, Controlling Nutritional Status; GNRI, Geriatric Nutritional Risk Index; RTI, respiratory tract infection.

Regarding the receiver operating characteristic analysis, an admission CONUT higher than 3.0 was found to predict all-cause mortality with a sensitivity of 77.8% and a specificity of 64.7% (area under the curve=0.778, p<0.001).

Discussion

The findings in this study indicated that nutritional status is associated with 90-day all-cause mortality in patients with hypertension aged >80 years. A CONUT score that was higher on admission was an independent predictor for all-cause mortality: 1.458 (95% CI 1.102 to 1.911, p=0.015). As CONUT score increased, the incidence of all-cause mortality likewise increased in patients admitted for both RTI (HR=1.284, 95% CI 1.013 to 1.740, p=0.020) and other reasons (HR=1.841, 95% CI 1.117 to 4.518, p=0.011).

The relationship between nutritional status, particularly malnutrition and prognosis of patients with cardiovascular disease has garnered increasing research interest.11 In a study including 2251 patients with a mean age of 65.0±12.8 years, multiple logistic regression analysis indicated that malnutrition is an independent factor influencing post-MI complications.12 Another Chinese study confirmed that nutritional status is independently associated with the risk of all-cause mortality in geriatric patients with CAD. Whether nutritional support in these types of patients improves clinical outcomes merits further investigation.13 A study involving subjects with heart failure indicated that poor nutritional status, as assessed via CONUT score, and atherosclerosis, as indicated via CIMT, are significantly associated with inflammation and predicts poor outcomes in patients with CHF.14 A relationship between nutritional status and prognosis in patients with hypertension is rarely observed; for elderly patients, such a relationship occurs even more rarely.

CONUT is calculated using laboratory data including Alb concentration, lymphocyte count and cholesterol level. This index can accurately reflect the nutritional status and immune function of the body. Previous reports on prognosis evaluation and CONUT have mostly focused on tumour or liver diseases. Yoshida et al,15 for example, found that a moderate or severe CONUT score is an independent risk factor for any morbidity and severe morbidities for oesophageal cancer. The same research team also concluded that CONUT is a convenient and useful tool for nutritional status assessment prior to oesophagectomy. Similar conclusions were drawn for patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma.16 Studies on cardiovascular disease have been rare in this regard, however.

A study on patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction showed that the CONUT score is associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality for both unadjusted and age-adjusted and sex-adjusted models; in a full-adjusted model, the best predictors were age and brain natriuretic peptide.17 In patients with CHF, a mean follow-up period of 28.4 months revealed that patients experiencing cardiovascular events had impaired nutritional status, higher CONUT scores, lower PNI scores and lower GNRI scores compared with patients who did not experience cardiovascular events.18 In this study, we found that only CONUT, not GNRI, is an accurate predictor for all-cause mortality in patients with hypertension up to 3 months after admission.

A study involving patients admitted to an acute geriatric unit showed that both Alb and CONUT are accurate predictors of short-term and medium-term mortality; however, the study added little to the information provided by Alb alone.19 Our results indicate that, for hypertensive patients admitted for other reasons, Alb and CONUT are independent predictors of all-cause mortality; for hypertensive patients suffering from RTI, however, only CONUT provided useful prognostic information. We therefore conclude that, for patients admitted with hypertension, CONUT is a valuable nutritional status index.

GNRI, which is determined based on the Alb and weight of the patient, is a relatively new index for the nutritional assessment for elderly patients.5 20 Past studies have shown that a higher-risk GNRI is positively correlated with length of hospital stay, although the association between higher-risk GNRI and in-hospital mortality is not significant.21 GNRI is the most widely used tool in chronic kidney disease with or without dialysis.9 22 23 Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis demonstrated that GNRI<100, serum ferritin≥500 mu g/L and age≥65 years are significant predictors for mortality in haemodialysis patients.24 Increased GNRI is also associated with increased CRP levels and low lymphocyte counts after multivariable adjustment. Some studies have also reported on GNRI as a prognostic factor in cardiovascular diseases.25 26 In this study, however, we found that GNRI is not an independent predictor for all-cause mortality in patients with hypertension.

The present study was not without limitations. First, it was a single-centre study that included a relatively small number of patients. Follow-up studies were only performed for only 90 days; a lengthier follow-up study is currently being conducted to further explore the results reported here.

Conclusion

We found that nutritional status assessed using CONUT and not by other nutritional index in hypertensive patients over 80 years can efficiently predict all-cause mortality within 90 days postadmission. Increased CONUT score was related to an increase in the incidence of all-cause mortality in patients admitted for RTI and other reasons. An accurate evaluation of nutritional status may provide additional prognostic information for such patients and management of nutritional status may significantly improve treatment outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to sincerely thank Professor Xue Changyong for his instructive advice and useful suggestions on this thesis.

Footnotes

Contributors: Guarantor of overall study integrity: LL. Design of the study: XS, LL and PY. Data collection and interpretation: XS and XZ. Statistical analysis: XS and LL. Manuscript preparation: XS and LL. Final approval of manuscript: XS, LL, XZ and PY.

Funding: This study was funded by a grant from the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Health Project (Project ID:14BJZ12).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Human Investigation Committee of People’s Liberation Army General Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article, and no additional data are available.

References

- 1. Arodiwe I, Chinawa J, Ujunwa F, et al. . Nutritional status of congenital heart disease (CHD) patients: burden and determinant of malnutrition at university of Nigeria teaching hospital Ituku—Ozalla, Enugu. Pak J Med Sci 2015;31:1140–5. 10.12669/pjms.315.6837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anaszewicz M, Budzyński J. Clinical significance of nutritional status in patients with atrial fibrillation: an overview of current evidence. J Cardiol 2017;69:719–30. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2016.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Das UN. Nutritional factors in the prevention and management of coronary artery disease and heart failure. Nutrition 2015;31:283–91. 10.1016/j.nut.2014.08.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cereda E, Klersy C, Pedrolli C, et al. . The geriatric nutritional risk index predicts hospital length of stay and in-hospital weight loss in elderly patients. Clin Nutr 2015;34:74–8. 10.1016/j.clnu.2014.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cereda E, Pedrolli C, Zagami A, et al. . Nutritional risk, functional status and mortality in newly institutionalised elderly. Br J Nutr 2013;110:1903–9. 10.1017/S0007114513001062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cereda E, Pedrolli C. The use of the geriatric nutritional risk index (GNRI) as a simplified nutritional screening tool. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87:1966–7. author reply 67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ignacio de Ulíbarri J, González-Madroño A, de Villar NG, et al. . CONUT: a tool for controlling nutritional status. First validation in a hospital population. Nutr Hosp 2005;20:38–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iseki Y, Shibutani M, Maeda K, et al. . Impact of the preoperative controlling nutritional status (CONUT) score on the survival after curative surgery for colorectal cancer. PLoS One 2015;10:e0132488 10.1371/journal.pone.0132488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beberashvili I, Azar A, Sinuani I, et al. . Geriatric nutritional risk index, muscle function, quality of life and clinical outcome in hemodialysis patients. Clin Nutr 2016;35:1522–9. 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu LS. Writing group of Chinese guidelines for the management of H. [2010 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension]. Zhonghua xin xue guan bing za zhi 2011;39:579–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luke JN, Schmidt DF, Ritte R, et al. . Nutritional predictors of chronic disease in a central Australian aboriginal cohort: a multi-mixture modelling analysis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2016;26:162–8. 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yoo SH, Kook HY, Hong YJ, et al. . Influence of undernutrition at admission on clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiol 2017;69:555–60. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2016.05.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang BT, Peng Y, Liu W, et al. . Nutritional state predicts all-cause death independent of comorbidities in geriatric patients with coronary artery disease. J Nutr Health Aging 2016;20:199–204. 10.1007/s12603-015-0572-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nakagomi A, Kohashi K, Morisawa T, et al. . Nutritional status is associated with inflammation and predicts a poor outcome in patients with chronic heart failure. J Atheroscler Thromb 2016;23:713–27. 10.5551/jat.31526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yoshida N, Baba Y, Shigaki H, et al. . Preoperative nutritional assessment by controlling nutritional status (CONUT) is useful to estimate postoperative morbidity after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. World J Surg 2016;40:1910–7. 10.1007/s00268-016-3549-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Du XJ, Tang LL, Mao YP, et al. . Value of the prognostic nutritional index and weight loss in predicting metastasis and long-term mortality in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Transl Med 2015;13:364 10.1186/s12967-015-0729-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Basta G, Chatzianagnostou K, Paradossi U, et al. . The prognostic impact of objective nutritional indices in elderly patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol 2016;221:987–92. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.07.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Narumi T, Arimoto T, Funayama A, et al. . Prognostic importance of objective nutritional indexes in patients with chronic heart failure. J Cardiol 2013;62:307–13. 10.1016/j.jjcc.2013.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cabré M, Ferreiro C, Arus M, et al. . Evaluation of CONUT for clinical malnutrition detection and short-term prognostic assessment in hospitalized elderly people. J Nutr Health Aging 2015;19:729–33. 10.1007/s12603-015-0536-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cereda E, Pedrolli C, Zagami A, et al. . Nutritional screening and mortality in newly institutionalised elderly: a comparison between the geriatric nutritional risk index and the mini nutritional assessment. Clin Nutr 2011;30:793–8. 10.1016/j.clnu.2011.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gärtner S, Kraft M, Krüger J, et al. . Geriatric nutritional risk index correlates with length of hospital stay and inflammatory markers in older inpatients. Clin Nutr 2017;36:1048–53. 10.1016/j.clnu.2016.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Formiga F, Ferrer A, Cruzado JM, et al. . Geriatric assessment and chronic kidney disease in the oldest old: the Octabaix study. Eur J Intern Med 2012;23:534–8. 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beberashvili I, Erlich A, Azar A, et al. . Longitudinal study of serum Uric Acid, nutritional status, and mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2016;11:1015–23. 10.2215/CJN.10400915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Edalat-Nejad M, Zameni F, Qlich-Khani M, et al. . Geriatric nutritional risk index: a mortality predictor in hemodialysis patients. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 2015;26:302–8. 10.4103/1319-2442.152445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaneko H, Suzuki S, Goto M, et al. . Geriatric nutritional risk index in hospitalized heart failure patients. Int J Cardiol 2015;181:213–5. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.11.167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Maruyama K, Nakagawa N, Saito E, et al. . Malnutrition, renal dysfunction and left ventricular hypertrophy synergistically increase the long-term incidence of cardiovascular events. Hypertens Res 2016;39:633–9. 10.1038/hr.2016.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.