Abstract

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is among the most disabling injuries, resulting in a range of cognitive impairments. Traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) often occurs in conjunction with TBI; the two are best considered together in the context of trauma to the central nervous system (CNS). Despite strong indications of cognitive dysfunction in CNS trauma, little is known about its natural history or relationship with other factors. The current protocol outlines a strategy for a systematic review of the current evidence examining CNS trauma as a prognostic factor of cognitive decline in the adult population.

Methods and analysis

The review will be conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. All peer-reviewed English language publications with a longitudinal design that focus on cognition in adults (ages 18 and older) with either TBI or SCI, or both from inception to December 2016 found through Medline, Central, Embase, Scopus, PsycINFO, supplemental PubMed and bibliographies of identified articles will be considered eligible. Quality will be evaluated using published guidelines. Results will be grouped by: (1) prognostic factors of cognitive deficits; and (2) development of, or time until development of, cognitive deficit in patients with CNS trauma. Close attention will be paid to the evaluative properties of the measurements used to assess cognition.

Ethics and dissemination

The authors will publish findings from this review in a peer-reviewed scientific journal(s) and present the results at national and international conferences. This work will advance scientific certainty regarding natural history and prognostic factors of cognitive status in males and females with CNS trauma, informing clinicians, policymakers and future researchers on the topic.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017055309.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury; traumatic spinal cord injury; cognition; Alzheimer’s disease; prognosis; natural history; males, females; Ia level of evidence; systematic review

Strengths and limitations of this study.

During the developmental phase of the project, concepts and hypotheses were formulated based on a synthesis of relevant discoveries across various disciplines and previous research.

The multilevel risk of bias assessment allows to detect main flaws in the individual studies’ design and inform future research on the topic.

Special attention will be paid to measurements used to assess cognitive function in patients with central nervous system (CNS) trauma.

Severe CNS trauma cases are expected to be under-represented in the inception cohorts and the majority of the patients are expected to be males; this would limit the precision of estimates and generalisability of results.

We acknowledge the chance of publication bias and a bias associated with exaggerating the estimate of the actual effect due to inclusion of only peer-reviewed studies published in English.

Introduction

Description of the condition

Central nervous system (CNS) trauma—including traumatic brain injury (TBI) and traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI)1—has been implicated as a risk factor for a range of cognitive impairments, particularly in the domains of attention, memory, emotion and behaviour.2–4 Recent studies have presented solid evidence that patients with a history of CNS trauma may develop various neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease (AD).4–6 However, our understanding of when (ie, post-injury time frame) and in whom (ie, characteristic of an injured person) AD dementia develops after CNS trauma (TBI, SCI or both)—with respect to sustained and/or degrading cognitive impairment post-injury—remains limited,4 7 8 and reported rates of cognitive decline after TBI and traumatic SCI are quite variable.9 10 This variability has prompted interest in longitudinal studies that have focused on cognition in persons with CNS trauma across their post-injury lifespans.11 12 To assess longitudinal changes in cognitive status post-injury, evaluative instruments or composite tests that are able to measure these changes in cognition after CNS trauma over time are crucial.13 A recent study was conducted on the factors associated with the rate of decline and evolution from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) to AD dementia in elderly patients, estimated from three common global measures of cognition. This study appeared to have findings that varied depending on the evaluative measure used.14 The study of measurements’ properties of cognition in patients with CNS trauma is still in its infancy, and—when reporting cognitive decline associated with CNS trauma—evaluative properties of measurements have rarely been discussed or acknowledged. In order to come to a robust conclusion on the course of cognitive status after TBI, appropriately evaluating the properties of measurements must be done in the process of data synthesis.

Description of measurements’ needs

Under the framework of Kirshner and Guyatt, measurements used to evaluate change over time in any domain should be: (1) reliable (ie, possess adequate internal consistency and responsiveness test–retest reliability in the population of interest) and (2) correspond closely to the construct to be measured.15 Until now, research on cognitive status after TBI has focused on patients’ ‘capacity’ (ie, what the patient can do when he or she is invited to), ‘perceived ability’ (ie, what the patient thinks they can do) and ‘cognitive activity’ (ie, what the patient can actually do), which are different constructs.13 As such, when assessing CNS trauma-related deficits in language, perception, memory, reasoning, attention, etc, a solid knowledge and understanding of the tests applied to measure these specific deficits is of great importance.

How sex might affect results

Another important area to consider in the study of cognition after CNS trauma and the risk of development of AD is sex (ie, biological differences between males and females). Often, CNS trauma is considered to be an injury of males. Overall and in almost every age group, TBI and SCI more frequently occur in males than in females.16 17 These differences may reflect the high rate of general injuries among males and/or differences in risk-taking societal roles and behaviours, that are relevant to the construct of gender, rather than sex.18 In contrast, the preponderance of current evidence indicates that an increased risk of AD exists in females, which is even more pronounced at an advanced age.19 The reason behind sex differences in the risk of AD is unknown, especially because many human studies support the notion that oestrogen, especially brain oestradiol, improves and conserves cognitive function including memory retention.20 21 Consistent with this theoretical gap, women’s traditional inequalities and disadvantages in access to and control of resources have resulted in the present scarcity of data on women with CNS trauma,22–24 and our knowledge of whether women and men are at different risks of developing cognitive impairments after CNS trauma due to differing gendered vulnerabilities (ie, injury risk, severity, access to power and resources post-injury, help-seeking behaviours, healthcare system use, intervention response and rehabilitation outcomes) or conversely, being protected from it, is limited.25 Therefore, an awareness of how cognitive status after CNS trauma varies by, or parallels by sex across time points when taking gender into account, is critical to advance CNS trauma and AD research.

How age might affect results

Age is the single-most important risk factor for various domains of cognitive decline across diverse cultural groups and geographic regions, including memory, language, processing speed and executive functioning.26 CNS neurogenesis is known to change during one’s lifespan, and this is likely reflected in age-related risk for cognitive decline. However, research has highlighted that associations may vary across cohorts,26 suggesting that different rates of cognitive decline might contribute to the global variation in age-related dementia prevalence. Likewise, consistent associations of cognitive function with genetics, cardiovascular health and lifestyle have been accumulated in research, each of which is relevant to the discussion of the higher likelihood of being involved in an injury with CNS outcome.27 The need to explore how age-dependent factors associate with other risk factors in patients with CNS trauma cannot be undermined.

Objectives

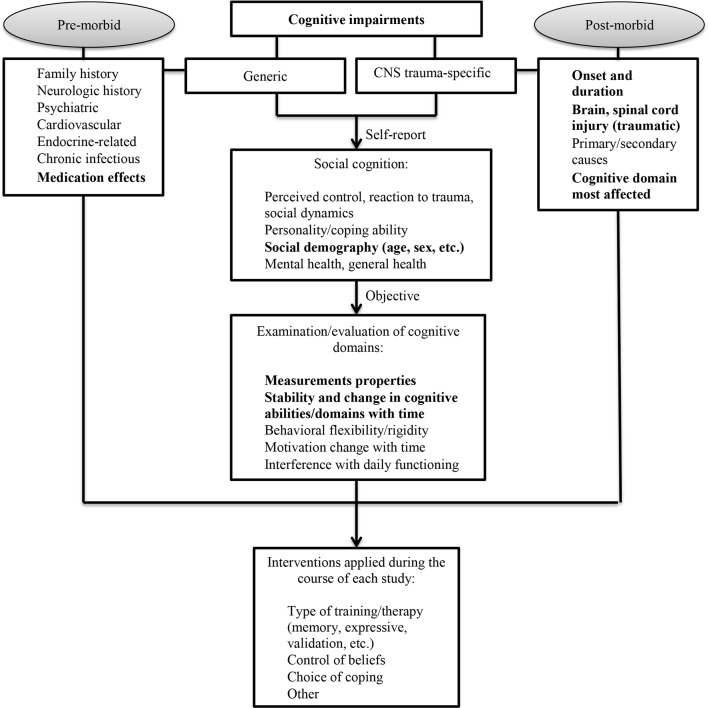

The aim of the current study is to identify, appraise and synthesise all available longitudinal studies relevant to the discussion of cognitive function in males and females following CNS trauma in an attempt to: (1) document the course of cognitive status (decline, improvement, stability, fluctuations, etc) in patients with CNS trauma as time since injury progresses; (2) determine prognostic factors of development of cognitive deficits in patients with CNS trauma from the baseline to follow-up; and (3) summarise sex- and age-stratified results pertaining to the course of cognitive status in patients with CNS trauma. Finally, the current study intends to provide a systematic consideration, solid description and in-depth understanding of the range of measurements used to assess cognition in CNS trauma research. This study also aims to report on these instruments’ test–retest reliability and construct validity, which are key psychometric properties necessary for evaluative purposes. This study is operating under the hypothesis which states that acutely derived CNS trauma variables alone (ie, age, sex, TBI mechanism, level of SCI, injury severity) are not sufficient to accurately predict cognitive status and/or its domains after CNS trauma. Furthermore, it is hypothesised that cognitive deficits following CNS trauma are the product of diverse external and internal influences acting on a genetically determined substrate and that many of these external influences are modifiable (figure 1). The current protocol outlines a strategy for this systematic review.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for summarising longitudinal evidence on cognitive status in patients after central nervous system (CNS) trauma (ie, traumatic brain injury (TBI), traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI) or both).

Methods and analysis

The review will be conducted and reported in compliance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.28 In accordance with these guidelines, the systematic review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO)29 on 16 January 2017 (registration number, CRD42017055309).

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies and setting

Peer-reviewed published longitudinal studies (ie, studies that have cognition on at least two separate occasions) in English, conducted in adults with a clinical diagnosis of CNS trauma (TBI, or SCI, or both) regardless of research setting. Studies of SCI of only traumatic origin will be considered.

Studies that were primarily designed to investigate the course and predictors of cognitive deficits in patients with CNS trauma.

Participants and assessment

Males and females aged 18 years or older, with TBI or SCI or both, defined by clinical criteria.

Any means of clinical diagnosis or standardised assessment of cognition. For more information, we refer the reader to the Constructs of cognitive function, cognitive deficits and AD section.

Types of outcome measures

The primary outcomes include (1) cognitive function or (2) development of—or time until development of—possible or probable cognitive deficit in patients with CNS trauma.

Constructs of cognitive function, cognitive deficits and AD

Cognitive function is referred to as the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thoughts, experiences and senses.30 It encompasses processes, such as knowledge, attention, memory and working memory, judgement and evaluation, reasoning and ‘computation’, problem solving and decision making, comprehension and production of language, etc.30 Any measures of cognition (or its domains) (eg, the presence or absence of cognitive deficits determined using a single question, a case definition of any measure of cognitive domain by a standardised clinical tool, or cognitive domain scores reported as a continuous variable) will be considered.

Development of a cognitive deficit in patients with CNS trauma will be assigned based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth edition (DSM-V) criteria for MCI, namely, (1) evidence of modest cognitive decline from a previous level of performance in one or more cognitive domains (complex attention, executive function, learning and memory, language, perceptual motor, or social cognition) based on: (i) concern of the individual, a knowledgeable informant, or the clinician that there has been a mild decline in cognitive function; and (ii) modest impairment in cognitive performance, preferably documented by standardised neuropsychological testing or, in its absence, another quantified clinical assessment; and (2) the cognitive deficits do not interfere with the capacity for independence in everyday activities (ie, complex instrumental activities of daily living such as paying bills or managing medications are preserved, but greater effort, compensatory strategies or accommodation may be required.)31

AD or dementia

This systematic review concerns sustained and/or degrading cognitive function post-injury, as well as cognitive complaints of uncertain clinical significance (ie, MCI with questionable deficits on quantitative tests) starting early after the injury. While at this time, there is sparse data on how many individuals with CNS trauma will eventually progress to definite AD, some TBI patients with MCI have shown, on autopsy, findings of histopathological AD.32 33 The animal literature has also demonstrated evidence of features of AD arising shortly after the onset of TBI.34 35 These results suggest that in patients with CNS trauma, MCI detected very early post-injury may represent the initial clinical presentation of AD. As part of this review, close attention will be paid to patients at risk of having a high probability of AD–patients with MCI at baseline/early after injury (particularly mild injury severity cases) but who have progressed rapidly into cognitive deficits within first few years post-injury, characterised by uniform progression of cognitive impairments in several domains (ie, memory, speech) and impaired activities of daily living. Further, the term dementia refers to a syndrome of brain dysfunction that is progressive and has many possible causes; we intend to study CNS trauma as a risk for cognitive decline, with an open view to the natural course of cognitive status (improvement, decline or relative stability) with time. Consequently, any sustained decline in cognitive status longitudinally is more reasonable in the discussion of risk of AD rather than dementia.

Exclusion criteria

Types of studies

Studies investigating cognition after CNS trauma due to secondary pathological processes (eg, oedema, intracranial haemorrhages, ischemia/infarction, vegetative/minimally conscious state, and systemic intracranial conditions).

Letters to editors and reviews without data, case reports or reports; conference abstracts, articles with no primary data, theses, grey literature and unpublished manuscripts.

Historical limiter (1993) is set to mTBI diagnosis, given that the diagnostic criteria for mTBI were introduced by the American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine in 1993 only.36

Search methods for the identification of studies

In collaboration with clinical experts and a medical information specialist, a comprehensive search strategy for studying cognitive function in CNS trauma was developed. All English language, peer-reviewed studies with prospective or retrospective data collection and a longitudinal design, found through Medline, Central, Embase, Scopus, PsycINFO and supplemental PubMed, were eligible. Searches in individual databases covered publications’ time frame from inception until early December 2016. The complete search strategy can be found in online supplementary file 1. We refer the reader to the Cochrane handbook and other published sources for justification of the selected databases.

bmjopen-2017-017165supp001.pdf (69.9KB, pdf)

Searching other resources

Reference lists of included studies will be reviewed to identify any additional studies.

Selection of studies

All searches will be saved in EndNote with duplicates removed. For the first level of screening, two reviewers (TM and NP or TM and AD) will read the titles and abstracts of all the citations from the electronic database searches and remove all citations not related to the primary research objectives. For the second level of screening, each reviewer will independently assess the full article. If the title or abstract suggests that the study might meet the inclusion criteria, each reviewer individually will assess the full text; any conflicting views will be resolved by discussion between reviewers and systematic review team members. If needed, clinical and research experts on the field will be contacted. Studies failing to meet the inclusion criteria will be excluded and the reason for exclusion will be reported.

Data extraction and management

For studies fulfilling the inclusion criteria, two review authors (AS or NP for descriptive data; TM and AS or NP for outcome data) will independently extract data into data collection forms grouped according to study design. The data from observational longitudinal studies will be used to address all research objectives. Randomised control trial (RCT) studies will be treated as cohort studies by abstracting data from the control (eg, untreated group) to address the first research objective (eg, to determine the course of cognitive deficits) in patients with CNS trauma.

The abstracted data will include the following: (1) study characteristics (author names, publication year, country of study, study setting, study design, sample size, method of measuring cognition and cognitive domains covered, number of participants assessed for at each time point, time between assessments and time since injury to each follow-up); (2) participant characteristics (mean age, sex, education, definition of CNS (ie, TBI, SCI), localisation/level of injury and injury severity); (3) medication regimen, if reported; and (4) results (reported frequencies of cognitive impairments, and all reported predictive associations between cognition and other variables (ie, age, sex, education, TBI severity, comorbidity)).

Data synthesis

Results of each study will be divided into two main categories: the course of cognitive deficits after CNS trauma and prognostic factors of cognitive function across assessment times.

To determine the course of cognitive deficits, matching assessment times (ie, time since diagnosis when cognitive function was measured) will be grouped by their corresponding frequencies and a sample size-weighted mean frequency value will be calculated for time points with more than one contributing frequency value (ie, more than one study reporting cognitive deficit at that time point). Results will also be grouped, if sufficient data exists, taking into account measurements used to assess cognitive function.

Prognostic factors associated with cognition and/or its domain(s) will be extracted from all cohorts (and untreated/without an effect RCTs). All factors influencing the course of cognitive values/status, as reported by the author, will be considered as prognostic factors. A prognostic association will be considered as significant if the reported p-value is ≤0.05, authors reported association as significant, or the 95% confidence intervals around a rate ratio or similar statistic did not exceed one, when adjusted for at least age and sex (ie, minimum set of confounders) in a multivariable model. Where a prognostic factor was assessed with respect to the outcome at several time points in the same cohort, data will be extracted and reported for each follow-up time.

Confounding effect

To address our research objective regarding the effect of CNS trauma on cognitive status, we will evaluate the literature regarding putative negative effects in the light of other factors known to affect cognition; age and sex will be considered as the minimum set of confounders associated with cognition at each time point. All other confounding factors (such as education, medication/illicit drug use effect, comorbidities) that may affect the generalisability of the study and interpretation of results will be explored and clearly described. In addition, the possible effects of measures used to assess cognition will be considered and special attention will be paid to measurements’ psychometric properties, particularly construct validity and test–retest reliability. Finally, given the nature of the research questions (ie, prognostic factors, course), which raises the issue of zero-time bias, studies will be grouped based on whether their baseline assessments were conducted before or after the 1 month post-injury mark. This time point was arbitrarily set.

Methodological quality and risk of bias assessment

Study quality will be assessed independently by two experienced reviewers using the Quality in Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) guidelines.37 38 The appraisal will consist of two steps: (1) assessment of six potential sources of bias (study participation and attrition, prognostic factors and outcome measurements, confounding measurement and account, and analyses) and (2) grading the presence of potential biases as ‘Yes’, ‘Partly’, ‘No’ or ‘Unsure’. To summarise the level of evidence, the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) methodology38 will be utilised: (1) ‘++’ when all or most of the quality criteria proposed by QUIPS are fulfilled (allowing one ‘Partly’ while appraising all potential sources of bias); (2) ‘+’ when some of the criteria are fulfilled; and (3) ‘-’ when few or none of the criteria are fulfilled (at least one ‘Yes’). As proposed by SIGN, studies with retrospective design will not receive a ‘++’ rating. Group (1) will be referred to as ‘high-quality studies’ and group (2) as ‘moderate-quality studies’. Results will be reported in a table format.

Finally, the consistency of the level of evidence will be summarised. Evidence will be designated ‘strong’ when consistent findings are found in multiple ‘moderate-quality’ or one or more ‘high-quality studies’ and the total sample size of combined eligible studies is ≥100; ‘moderate’ when consistent findings in multiple ‘moderate-quality’ or one ‘high-quality’ quality study with a total sample ≥50, or at least one ‘moderate-quality’ or ‘high-quality’ quality study with a total sample of 50–99; ‘limited’ when findings are found in at least one ‘moderate-quality,’ or ‘high-quality’ quality study with total sample size between 25 and 49; and ‘unknown’ when findings are of indeterminate rating, in studies with poor methodological quality or with a sample of <25.38 To ensure the explicit basis for bias assessment, aspects of the trial methods on which the judgement for ‘high risk of bias’ will be based as well as the judgement itself—including the trial method on which the decision of exclusion was based—will be reported.

Measurements: description and properties evaluation

Using a standardised form developed for a previous systematic review on measurements’ properties,39 details of included measurements will be extracted from original studies and manuals—where available—and studies that evaluated their psychometric properties. The following descriptors will be extracted and reported: general characteristics, purpose and content, method of administration, respondent burden, language (and translations), psychometric properties, particularly test–retest reliability and construct validity, and strengths and cautions for application in patients with CNS trauma.39 Measurements will then be categorised into the following groups: (1) global measures of cognition; (2) domain-specific measures of cognition; and (3) multi-domain measures, which include items (subscales) of cognition among other functions.40 Based on the above descriptors and using the Holmbeck et al’s evidence-based assessment criteria,41 a rating will be assigned—‘well-established assessment’, ‘approaching well-established assessment’ or ‘promising assessment’ in patients with CNS trauma—to each included measurement.

Given the diversity in measurements of domains of cognitive function, severity and localisation of CNS trauma, as well as the high likelihood of the diversity of statistical methodology used to express associations, a best-evidence synthesis approach42 will be applied, synthesising findings from studies with sufficient quality through tabulation and qualitative description. Some features falling under meta-analysis constructs (ie, sample size-weighted mean frequencies) will be considered only for the first research question (ie, the course of cognitive deficits). As indicated above, for studies focusing on the same domain of cognitive deficits prevalence (ie, executive function, memory or other), sample size-weighted mean frequencies will be collected and matching assessment times (ie, time post-injury that each domain of the cognitive function was measured) will be grouped with their corresponding frequencies. A sample size-weighted mean frequency value will be calculated for time points with more than one contributing frequency value (ie, more than one study reporting values at that time point post-injury).

Dealing with missing data

In cases of missing data, primary authors will be contacted. The proportion of missing data will be reported along with reasons, where indicated. In the case of duplicate publications and companion papers of a primary study, we will attempt to yield maximum scientific information by abstraction of all available data. Nonetheless, original publication (usually the oldest version) will take priority in data analysis.

Ethics and dissemination

This systematic review will provide increased scientific certainty about the prognostic factors and natural history of cognitive status in patients with CNS trauma, informing clinicians, policymakers and subsequent studies funded by the Alzheimer’s Association. The strength of this systematic review protocol and research programme is in its methodology, making it possible to identify associations longitudinally, thus improving the quality of inductive inferences about the natural progression of cognitive status in patients with CNS trauma. The multilevel risk of bias assessment will allow researchers to detect main flaws in the designs of individual studies and to inform future research on the topic of cognition in CNS trauma. During the development phase of the project, concepts and hypotheses were formulated based on a synthesis of relevant discoveries across various disciplines. It is evident that the content of measurements and their psychometric properties can influence estimates of cognitive impairment across time points (ie, natural history research aim) as well as the predictors of cognition in patients with CNS trauma. Likewise, earlier research has highlighted that different domains of cognition are affected differently in TBI and SCI based on type, localisation and severity of injury and that the perception of a person with CNS trauma can also be influenced by the duration of cognitive impairment (ie, individuals could have adjusted to their long-term impairment, making them less likely to recognise their degree of impairment). To mitigate these issues, a variety of data related to the domains of each measure will be collected and reported on. This approach will help researchers think about elements that constitute cognition in patients with CNS trauma, increasing the comprehensiveness of understanding and the appreciation/relevance of the measurement theory in the study of cognition. Finally, multi-level knowledge translation activities (publications, presentations, research-knowledge user collaborations) throughout this research activity will be performed. This will ensure that the programme results reach their intended knowledge users with the goal of informing innovations in AD and CNS trauma research, health policy and practice.

Limitations

Certain features of this review are open to debate. Those features include the following: (1) The assumption of expected heterogeneity in the primary studies with respect to sample characteristics (ie, age, injury/localisation of injury, time since injury) and the applied measurements of cognition properties and content; (2) potentially unequal sex distribution in primary studies, given that historically both TBI and SCI have been considered an injury-specific to males; (3) age, a potential predictor of cognitive decline, may not be always reported as a continuous variable or in similar ranges; therefore, assessment of the age factor would be limited to those studies that reported it; (4) potential confounders, such as medication effects/illicit substance use and comorbidity load, may not be adequately explored given the lack of consistent reports and effect consideration in TBI research43; nonetheless, where possible, such effects will be explored; (5) baseline assessments of cognition in patients with CNS trauma are expected to vary between studies: while the issue was predicted and attempts will be made to mitigate the zero-time effect by reporting results with baseline assessments up to 1-month post-injury and after 1 month; separately, pre-morbid assessments of cognition are unlikely to be understood, and therefore, the generalisability of the results may remain unclear due to inadequate control of the confounding effects of premorbid cognitive functioning; (6) additional limitations relate to the exclusion of grey literature, non-English language articles and unpublished manuscripts and their potentially relevant results; this decision was based on the extensive number of studies identified within databases we have searched, as well as limited empiric evidence about the potential impact of selective searching and inclusion of these works on the results of systematic reviews.44

Despite the outlined limitations, this is the first review of its kind to consciously and comprehensively synthesise evidence on the cognitive status in patients with CNS trauma, aiming to advance scientific knowledge in the field and enrich the care provided to patients with cognitive impairments stemming from TBI and traumatic SCI.

Implications

An ageing population will increase the burden of CNS trauma as the number of people surviving after the injury progressively increases. While the neurological consequences of CNS trauma are well described, evidence is emerging on sex-dependent/age-dependent associations between a prior injury (most frequently TBI) and the development of senile Alzheimer’s-type dementia many years later. Diagnostic criteria, first established by the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke, were revised in light of the discovery of new markers—amyloid-B and tau proteins—accumulation of which brings cognitive dysfunction and neuronal death. These markers, shown to be non-specific in AD, appeared to be similar in persons with TBI and fatal familial insomnia. To fill the gap that is left by current evidence-based practice, the proposed study will lay the ground for further research aimed at determining the underlying basis behind any observed patterns. The significant economic and human costs of cognitive dysfunction years after CNS trauma merit the call for systematic efforts to understand the factors that contribute to its development. This research looks to motivate future investigations of AD and CNS trauma in numerous directions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the involvement of Ms Jessica Babineau, information specialist at the Toronto Rehabilitation Institute-University Health Network, for her help with the literature search. We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Dr Terence Quinn of the University of Glasgow (Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Team) for critically reviewing the protocol and providing constructive feedback and endorsements on important methodological considerations.

Footnotes

Contributors: TM and AC contributed to the conception of the research programme. TM developed the idea, designed the protocol and built the graphic data representation (eg, tables, figure). AC provided expertise at each level and also reviewed the protocol. TM wrote the first draft, which was reviewed by AC. TM registered the protocol with PROSPERO. TM wrote the first draft, which was reviewed by AC. NP and ADs contributed to the revisions of the protocol and highlighted areas in need of refinement of scientific terms based on the results of the initial screening (ie, first screen) that they performed.

Funding: This research programme is supported by the postdoctoral research grant to TM from the Alzheimer’s Association (AARF16442937). AC is supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research Grant—Institute for Gender and Health (#CGW126580). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Valenzuela V, Oñate M, Hetz C, et al. Injury to the nervous system: a look into the ER. Brain Res 2016;1648:617–25. 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.04.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Phillips AA, Squair JR, Currie KD, et al. ParaPan American Games: autonomic function, but not physical activity, is associated with Vascular-Cognitive impairment in spinal cord Injury. J Neurotrauma 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wu J, Zhao Z, Kumar A, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and Disrupted Neurogenesis in the Brain are associated with cognitive impairment and Depressive-Like behavior after spinal cord Injury. J Neurotrauma 2016;33:1919–35. 10.1089/neu.2015.4348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Muccigrosso MM, Ford J, Benner B, et al. Cognitive deficits develop 1month after diffuse brain injury and are exaggerated by microglia-associated reactivity to peripheral immune challenge. Brain Behav Immun 2016;54:95–109. 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nott MT, Baguley IJ, Heriseanu R, et al. Effects of concomitant spinal cord injury and brain injury on medical and functional outcomes and community participation. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2014;20:225–35. 10.1310/sci2003-225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. LoBue C, Wadsworth H, Wilmoth K, et al. Traumatic brain injury history is associated with earlier age of onset of alzheimer disease. Clin Neuropsychol 2017;31:85–98. 10.1080/13854046.2016.1257069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Collins-Praino LE, Corrigan F. Does neuroinflammation drive the relationship between tau hyperphosphorylation and dementia development following traumatic brain injury? Brain Behav Immun 2017;60:369–82. 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nordström P, Michaëlsson K, Gustafson Y, et al. Traumatic brain injury and young onset dementia: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Neurol 2014;75:374–81. 10.1002/ana.24101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li Y, Li Y, Li X, et al. Head Injury as a Risk Factor for Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 32 Observational Studies. PLoS One 2017;12:e0169650 10.1371/journal.pone.0169650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wecht JM, Bauman WA. Decentralized cardiovascular autonomic control and cognitive deficits in persons with spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med 2013;36:74–81. 10.1179/2045772312Y.0000000056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Himanen L, Portin R, Isoniemi H, et al. Longitudinal cognitive changes in traumatic brain injury: a 30-year follow-up study. Neurology 2006;66:187–92. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000194264.60150.d3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Craig A, Nicholson Perry K, Guest R, et al. Prospective study of the occurrence of psychological disorders and comorbidities after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2015;96:1426–34. 10.1016/j.apmr.2015.02.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. deVet CHW, Terwee CB, Mokkink LB, et al. Measurements in Medicine Practical Guide: Cambridge University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Monsell SE, Liu D, Weintraub S, et al. Comparing measures of decline to dementia in Amnestic MCI subjects in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) Uniform Data Set. Int Psychogeriatr 2012;24:1553–60. 10.1017/S1041610212000452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Guyatt GH, Kirshner B, Jaeschkle R. Measuring health status: what are the necessary properties? J Clin Epidemiol 1992;12:1341–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feigin VL, Theadom A, Barker-Collo S, et al. Incidence of traumatic brain injury in New Zealand: a population-based study. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:53–64. 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70262-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hagen EM, Rekand T, Gilhus NE, et al. Traumatic spinal cord injuries--incidence, mechanisms and course. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2012;132:831–7. 10.4045/tidsskr.10.0859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Definitions of sex and gender. 2015. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/47830.html (accesse 17 Mar 2017).

- 19. Mielke MM, Vemuri P, Rocca WA. Clinical epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease: assessing sex and gender differences. Clin Epidemiol 2014;6:37–48. 10.2147/CLEP.S37929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vahaba DM, Remage-Healey L. Brain estrogen production and the encoding of recent experience. Curr Opin Behav Sci 2015;6:148–53. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2015.11.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Li R, Cui J, Shen Y. Brain sex matters: estrogen in cognition and Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2014;389(:13–21. 10.1016/j.mce.2013.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mollayeva T, Colantonio A, Gender CA. Gender, sex and traumatic brain Injury: transformative science to optimize patient outcomes. Healthc Q 2017;20:6–9. 10.12927/hcq.2017.25144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. O’Reilly K, Wilson N, Health PK. Activity and participation issues for women following traumatic brain injury. Disabil Rehabil 2017:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stock D, Cowie C, Chan V, et al. Determinants of admission to Inpatient Rehabilitation among acute care survivors of Hypoxic-Ischemic brain Injury: a prospective Population-Wide Cohort Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016;97:885–91. 10.1016/j.apmr.2016.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cancelliere C, Donovan J, Cassidy JD. Is sex an Indicator of Prognosis after Mild traumatic brain Injury: a Systematic analysis of the findings of the World Health Organization Collaborating Centre Task Force on Mild traumatic brain Injury and the International Collaboration on Mild traumatic brain Injury Prognosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2016;97:S5–S18. 10.1016/j.apmr.2014.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lipnicki DM, Crawford JD, Dutta R, et al. Age-related cognitive decline and associations with sex, education and apolipoprotein E genotype across ethnocultural groups and geographic regions: a collaborative cohort study. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002261 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mollayeva T, Kendzerska T, Mollayeva S, et al. Sleep apnea after traumatic brain injury: understanding the impact on executive functioning. J Sleep Disorders: Treat Care 2013;2:5. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. NHS. PROSPERO-International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30. Andringa TC, Bosch KA, Wijermans N. Cognition from life: the two modes of cognition that underlie moral behavior. Front Psychol 2015;6:362 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed DC: WashingtonAmerican Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sennik S, Schweizer TA, Fischer CE, et al. Risk factors and pathological substrates associated with Agitation/Aggression in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Preliminary Study using NACC Data. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;55:1519–28. 10.3233/JAD-160780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Crane PK, Gibbons LE, Dams-O’Connor K, et al. Association of traumatic brain Injury with Late-Life Neurodegenerative Conditions and Neuropathologic findings. JAMA Neurol 2016;73:1062–9. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.1948 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gerson J, Castillo-Carranza DL, Sengupta U, et al. Tau Oligomers Derived from traumatic brain Injury Cause Cognitive impairment and accelerate onset of pathology in Htau mice. J Neurotrauma 2016;33:2034–43. 10.1089/neu.2015.4262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Iino M, Nakatome M, Ogura Y, et al. Real-time PCR quantitation of FE65 a beta-amyloid precursor protein-binding protein after traumatic brain injury in rats. Int J Legal Med 2003;117:153–9. 10.1007/s00414-003-0370-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hayden JA, Côté P, Bombardier C. Evaluation of the quality of prognosis studies in systematic reviews. Ann Intern Med 2006;144:427–37. 10.7326/0003-4819-144-6-200603210-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Published guidelines. 2017. www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/ (accessed 15 Feb 2017).

- 38. van Tulder M, Furlan A, Bombardier C, et al. Editorial Board of the Cochrane Collaboration Back Review Group. Spine 2003;28:1290–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mollayeva T, Kendzerska T, Colantonio A. Self-report instruments for assessing sleep dysfunction in an adult traumatic brain injury population: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 2013;17:411–23. 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wesson J, Clemson L, Brodaty H, et al. Estimating functional cognition in older adults using observational assessments of task performance in complex everyday activities: a systematic review and evaluation of measurement properties. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016;68:335–60. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Holmbeck GN, Thill AW, Bachanas P, et al. Evidence-based assessment in pediatric psychology: measures of psychosocial adjustment and psychopathology. J Pediatr Psychol 2008;33:958–80. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Slavin RE. Best evidence synthesis: an intelligent alternative to meta-analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 1995;48:9–18. 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00097-A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mollayeva T, Kendzerska T, Mollayeva S, et al. A systematic review of fatigue in patients with traumatic brain injury: the course, predictors and consequences. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2014;47:684–716. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hartling L, Featherstone R, Nuspl M, et al. Grey literature in systematic reviews: a cross-sectional study of the contribution of non-English reports, unpublished studies and dissertations to the results of meta-analyses in child-relevant reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 2017;17:64 10.1186/s12874-017-0347-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-017165supp001.pdf (69.9KB, pdf)