Abstract

Objectives

Despite varying degrees in research training, most academic clinicians are expected to conduct clinical research. The objective of this research was to understand how clinical researchers of different skill levels include variables in a case report form for their clinical research.

Setting

The setting for this research was a major academic institution in Beijing, China.

Participants

The target population was clinical researchers with three levels of experience, namely, limited clinical research experience, clinicians with rich clinical research experience and clinical research experts.

Methods

Using a qualitative approach, we conducted 13 individual interviews (face to face) and one group interview (n=4) with clinical researchers from June to September 2016. Based on maximum variation sampling to identify researchers with three levels of research experience: eight clinicians with limited clinical research experience, five clinicians with rich clinical research experience and four clinical research experts. These 17 researchers had diverse hospital-based medical specialties and or specialisation in clinical research.

Results

Our analysis yields a typology of three processes developing a case report form that varies according to research experience level. Novice clinician researchers often have an incomplete protocol or none at all, and conduct data collection and publication based on a general framework. Experienced clinician researchers include variables in the case report form based on previous experience with attention to including domains or items at risk for omission and by eliminating unnecessary variables. Expert researchers consider comprehensively in advance data collection and implementation needs and plan accordingly.

Conclusion

These results illustrate increasing levels of sophistication in research planning that increase sophistication in selection for variables in the case report form. These findings suggest that novice and intermediate-level researchers could benefit by emulating the comprehensive planning procedures such as those used by expert clinical researchers.

Keywords: qualitative research, clinical study, data collection, research design

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study used qualitative interviews to explore the novel topic of how researchers create a case report form.

The study involved the development of three visual models to depict the approach of novice, excellent and expert clinical researchers.

The expert clinical researchers shared guiding principles they use to conduct research.

A limitation of our study concerns the potential selection bias of our sample as clinician participants are from a premier academic hospital in Beijing, and these participants might have greater knowledge, cognitive skills and opportunities for research than clinicians in many other hospitals in China.

Introduction

Conducting clinical research is a multistage process. It can be divided into three stages: the first stage is top-level design; the second stage is protocol design and implementation; the third stage is conducting data analysis, interpretation and writing of the paper.1 During the first two stages, researchers should consider what variables are important and how to collect the data.

A case report form (CRF) is an instrument to structure and facilitate collection of data for clinical research.2 Most CRFs are customised to collect data specific to a particular clinical study protocol. Case report form development represents a significant part of the clinical trial process and can impact study success. A well-designed CRF is required for database construction, data accuracy, data query/cleaning, CRF completion and statistical analysis.

In the Research Center of Clinical Epidemiology, to facilitate greater clinical research efficiency, the question that how to develop an approach to build a CRF became meaningful. This interest extended to both the structure and variables of the CRF. The structure has been the topic of concern among some researchers.3–11 In one published paper, Li et al emphasise that the design of CRF needs the cooperation and efforts of each member of the study group.7 In another related paper, Wan et al note that the CRF should maintain privacy for participants, include a tracked page or modules and some other fields on forms.10 However, the question about what variables should be included in CRF has received less consideration despite its crucial role in the quality of clinical research.

The goal of this qualitative research study was to explore how clinical researchers select variables for a CRF and was part of a larger mixed-methods project to develop an approach for clinical researchers to build systematic variables for clinical research. These findings of this research could provide an approach for choosing variables in a CRF by clinical researchers. This can serve as a reference to other researchers and lay a foundation for further inquiry into what variables to include in a CRF.

Method

Qualitative inquiry is an approach particularly useful when little is known about the phenomenon under study.12 As little is known about how clinicians determine variables to include in a CRF, it was deemed a qualitative approach as useful.

Setting

The setting for this research was a heavily research-focused major academic institution and also is a university hospital in Beijing, China.

Study population

These hospitals are host to over 1000 faculty, and to some degree there is an expectation or hope that all will engage in clinical research at some level. Maximum variation sampling13 was used in this study. The target population was clinical researchers with three levels of experience, namely, limited clinical research experience, clinicians with rich clinical research experience and clinical research experts. Seventeen clinical researchers chose to participate in this study.

Data collection instrument

A semistructured interview guide was first developed based on a group discussion and a preliminary pilot study with two clinical researchers. The primary interview question developed to generate data for the study was, ‘What process do you use to design a case report form for clinical research?’ Key probes were, ‘What are the difficulties and challenges encountered when you designed case report form for your project?’ and ‘What is your previous experience joining a clinical research project?’ The overall interview guide was designed for a study looking comprehensively at clinical researchers’ approaches to data collection and thus had additional questions in the interview guide as well.

Recruitment

Individuals targeted for enrolment were contacted by email by a research assistant. We used maximum variation sampling to identify individuals with different degrees of research experience and different medical specialties in the project’s host academic institution, a teaching hospital and clinical research institute in Beijing.

The inclusion criteria were:

Meet one of the following conditions: (1) clinicians with limited clinical research experience who were defined as rarely participating in clinical research, a criterion operationalised as no experience to one experience designing a CRF for clinical research; (2) clinicians with rich clinical research experience defined as researchers with experience participating in several clinical research studies and experience designing three to nine data collection reforms or case report forms for clinical research and (3) clinical research experts defined as researchers with experience in clinical research for 5 years or more and participation directly in 10 or more clinical research projects.

Data collection

Two research assistants (RAs), both females with a PhD, conducted interviews from June to September in 2016. The RAs first conducted one focus group interview with clinicians who had limited experience in clinical research. As gathering busy clinicians for focus group interviews proved difficult, the RAs changed to face–to-face semistructured in-depth interviews with an additional nine clinicians and four clinical research experts. The same questions were posed in the same order to all the participants, whether the interviews were conducted in the focus group or individual interviews. One question was added for the four clinical research experts, namely, ‘What have you encountered when you directed other clinical researchers’ project’. The interviews lasted between 25 and 40 min and were conducted in a location that was quiet without interruption, either on the participant’s office or on the interviewee’s conference room. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim into Chinese. Data collection was complete after 17 interviews, the point when saturation of themes was reached.

Data analysis

The transcribed data were analysed in Chinese using thematic analysis with an inductive approach. Nvivo V.11 was used to assist in the analysis of the data. Two researchers (CH and ZL) independently coded and analysed the transcripts by: selecting the units of analysis, making sense of the transcribed data, developing codes, categorising the data and abstracting.14 The analysis focused on text from the four primary questions noted above but also used related information from other interview guide questions and context-specific language probes. The analysts discussed and reached an agreement on the coding and categorisation after reviewing one interview. The two researchers independently coded the remaining transcripts. Differences were minimal. All research team members agreed with the final results in a final discussion meeting. After constructing the models, the team confirmed the findings by checking the results with the interviews’ transcript. Member checking was used to share the results with all the interviewees by email—they raised no objections or new considerations and agreed with the findings.

Below, the findings of the study are presented by illustrating the three identified models and illustrative quotes from the interviews. The researchers who conducted the data collection and analysis translated the quotes selected for this article into English. Original quotes are available on request.

Ethical considerations

The institutional review board at Peking University Third Hospital approved the study. Each participant was informed about the study procedures and was free to withdraw from the research. All participants provided consent to participate in the study including audiotaping and transcription of the interviews by providing written informed consent. Potentially identifying information was removed from each transcript and each interviewee was assigned a unique identification number to protect his/her anonymity.

Results

The 17 clinical researchers had diverse backgrounds, including otolaryngology, pharmacy, endocrinology, orthopaedics, anaesthesia, radiology, neurology, cardiology, nephrology, haematology, thoracic surgery, epidemiology and biostatistics, clinical epidemiology, clinical research data management and clinical research methodology (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of the participants

| Participants level | Clinicians with limited clinical research experience | Clinicians with rich clinical research experience | Clinical research experts |

| Number | 8 | 5 | 4 |

| Gender | |||

| Male (N) | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Female (N) | 6 | 3 | 1 |

| Average age (mean±SD) | 27±4 | 35±2 | 44±12 |

| Department | Otolaryngology, pharmacy, endocrinology, orthopaedics, anaesthesia, radiology, neurologist, cardiology | Nephrology, otolaryngology, thoracic surgery, haematology | Epidemiology or clinical research methodology |

| Experience in clinical research (projects) | Participating in clinical research work for 1–3 years | Being involved in 5–12 clinical research projects | Working in clinical research for 11–20 years |

| Data collection | Four semistructured in-depth interviews and one focus group interview for four clinicians | Semistructured in-depth interviews | Semistructured in-depth interviews |

A typology of how clinical researchers of different skill levels include variables in CRF for clinical research

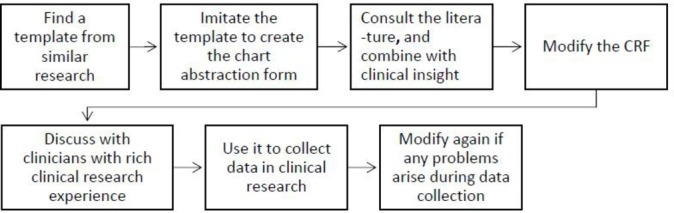

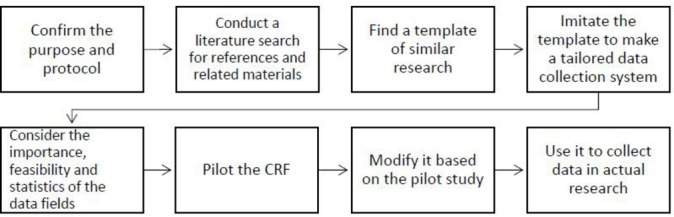

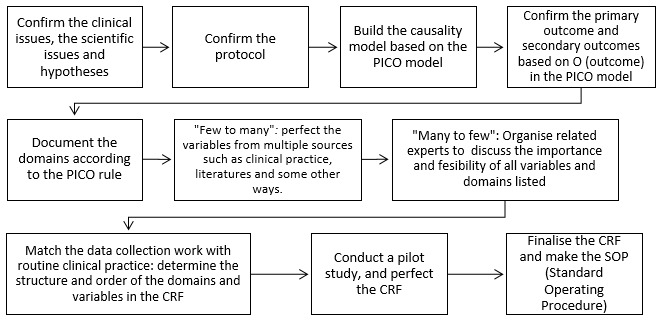

Based on our analysis, we developed a typology of how clinical researchers of different skill levels select variables in a CRF for clinical research. These three models are illustrated as figures 1, 2 and 3. The findings are supported by quoted comments from the research participants. The models are illustrated using a flow chart showing the different process for each of three levels of the participants, for example, novice clinicians with limited clinical research experience, intermediate-level clinicians with rich clinical research experience and clinical research experts.

Figure 1.

Novice clinical researchers’ approach to developing a CRF for clinical research. CRF, case report form.

Figure 2.

Experienced clinical researcher’s approach to selecting variables in a CRF for clinical research. CRF, case report form.

Figure 3.

The expert clinical researcher’s approach to selecting variables in a CRF for clinical research. CRF, case report form; PICO, patient/population/problem—intervention—comparison—outcome.

The novice clinical researcher’s approach to selecting variables in a CRF for clinical research

Novice clinicians with limited clinical research experience described a multifaceted approach to selecting variables for inclusion in their CRFs. When they planned the variables to include in their CRFs, most had no clearly defined comprehensive approach.

Finding the template from similar research and imitating it

Most novice clinical researchers mentioned that they would find a similar data collection form for reference and modify it according to the needs of their own study. As one endocrinologist noted, “First, I search on the Internet to find a template from similar research, then I modify the template based on my research”. One otolaryngology clinician said, “I ask for a data collection template from other experienced researchers in my department. I then imitate the template to make my own data collection template, and modify it in places according my research.” An orthopaedics clinician reflected his opinion that most novice clinical researchers are doing like this, “I will imitate another data collection template, then copy what is applicable to my research, and modify those variables that are not applicable. I think most of us follow, because it is easier for us.”

Discussing with clinicians with rich clinical research experience

Some novice clinical researchers reported discussing the CRF with experienced clinical researchers. One participant recounted, “I discussed the CRF with clinicians with rich experience in clinical research. They deleted useless items directly.”

Modifying again if any problems are found during use

Some novice clinical researchers directly used the data collection form without a pilot study and modified it only when they found problems during use. An anaesthesia clinician said, “When the CRF is used to collect data in a clinical research project, some variables are found not to be applicable or absent. In this case, I always think about it and then modify/add the variables.” Another cardiology clinician also remarked, “When I use the CRF to collect data from the first few participants, I find some variables can’t get data at all. So I realise that these variables also can’t get data from other participants, and these variables can contribute little to my research. Then I delete them.”

The following flow chart was refined from the above in-depth interviews with four clinicians and a group interview with another four clinicians.

The experienced clinical researcher’s approach to selecting variables in a CRF for clinical research

Experienced clinical researchers also described a multifaceted approach for how they include variables in a CRF. Most of them have a clear purpose and protocol first, and think about the importance, feasibility and statistics of these variables according to their experience in clinical research.

Confirming the purpose and protocol

These clinical researchers first concern themselves with confirming the purpose and developing a protocol before designing the CRF. For example, a nephrologist said, “First, you should confirm the purpose of your study, disease features or prognosis, follow-up study or cross-sectional study.”

Conducting a literature search for references and related materials

Most of the experienced clinical researchers would review the literature and related materials to consider the variables for inclusion in the CRF. “I think searching the related literature and other references is important. You can find many variables mentioned in other’s research. You also can list all the related items for reference.”

Finding a template from similar research and intimating it

Experienced clinical researchers also find a template to imitate for their own study. However, they consider the variables according to the research protocol, literature and their previous experience. One haematologist explained, “(I) search materials first, then find a template from the literature or similar research previously conducted in my department. Then I imitate the template to make CRF for my project, and optimize and perfect the CRF according to the research protocol”.

Consider the importance, feasibility and statistics of fields

The experienced clinical researchers note that the importance, feasibility and statistical analysis of collected variables should be considered before deciding whether to collect the data in the first place. One haematologist said, “Even if we do the optimizing and perfecting, we can also find many problems when we use it to collect data in clinical research. We can just modify it again and again. In the final version, many variables are deleted that are not easy to collect, or not very clear, or have little relationship with the primary outcome”.

Conduct a pilot study and modify the CRF

These experienced researchers also note that piloting the CRF before using it to collect data is very important. If any problems are found in the pilot study, the problem can be resolved in a timely way. A thoracic surgeon shared, “A pilot study was conducted after the draft CRF was completed. We then recruited some patients to complete it. We found that some items or scales could not be completed. For example, the tinnitus handicap inventory is too complex for patients. And it is not very important for the final evaluation about the treatment, so we deleted it in follow-up visits”.

The flow chart depicted in figure 2 illustrates the overall steps employed by these experienced clinicians based on their interviews.

The clinical research experts’ approach to selecting variables in a CRF for clinical research

Clinical research experts described their multifaceted approach to identifying variables for inclusion in a CRF or how they help other researchers design a CRF. They would consider the study comprehensively, and they raised some different and important views.

Confirming the clinical and scientific issues, hypotheses and research protocol

A clear research question and hypotheses are essential before you consider which variables should be included in the CRF. One expert working in the epidemiology research centre stated, “First, you complete the top-level design of the clinical research to confirm the clinical issues, scientific issues and hypotheses, and then confirm the research purpose and protocol”.

PICO model is considered to build the causality model

The PICO model is a format used to help define the clinical research question. P stands for patient/population/problem; I stands for intervention/prognostic factor/exposure; C stands for comparison; O stands for outcome sought to measure or achieve.15 The PICO model as commonly used in evidence-based medicine, can be employed to build a causality model and clearly confirm the related variables in the CRF. Another clinical research expert working in the epidemiology research centre explained, “In clinical research, you need to confirm the PICO, and build the causality model based on the PICO model. Then confirm the primary outcome and secondary outcome based on O (outcome) in PICO model”. “You need to document the domains based on the PICO model. These domains include but are not limited to population characteristics, intervention or exposure and related outcome, and related confounding factors affecting the causality between the intervention and outcome.”

What’s more, ‘few to many’ and ‘many to few’ are used to list and screen domains and variables in the research

Many clinical researchers worry about omitting key variables in the CRF, so they often list as many variables as possible. However, many variables are not necessary, and the added burden of collecting these data may even lower the quality of key variables. One expert in the clinical research institute emphasised that, “‘From less to more’, you need to list variables from all domains as much as possible through multiple ways such as clinical practice experience and literature. ‘Many to few’, we should organize related experts including clinicians, statisticians, data manager and experts on clinical research design to discuss the necessity and feasibility of all the domains and variables. It should be considered in terms of accuracy, sensitivity and difficulty of detection and collection, statistics, ethical problems, cost, quality control and so on”. The flow chart depicted in figure 3 illustrates the overall steps used by these four clinical research experts.

Discussion

This qualitative study reveals a different process of selecting variables for inclusion in a CRF for clinical research among three different levels of clinical researchers. Novice, experienced and expert clinical researchers have progressively sophisticated approaches for selecting variables in a CRF for clinical research. The novice clinician researcher approach of finding a template, modifying it according to their own study, reviewing it with clinicians with rich clinical research experience and then completing the CRF when collecting data can be problematic. This process can truncate thinking about the whole protocol, study purpose, statistics and so on and risks compromising the study quality. This point is consistent with previous discussion of Ioannidis et al 16 that research in a previously understudied domain might supply too little information to be useful. The resulting risk is small uninformative studies that remain common in several specialties.

Relative to the existing literature about the development of CRFs, this research has expanded understanding about what variables should be included in a CRF, procedures used by expert researchers for first greatly increasing and then limiting the range of variables to be studied. The notion of ‘few to many’ and ‘many to few’ to first comprehensively generate, then severely truncate to limit the domains is similar to previous advice. Li et al suggest collecting data so as to be able to just answer the scientific issues or hypothesis, nothing more and nothing less.7

Based on views from the novice to the expert clinician, the take away message from this research is that increasing levels of sophistication in research planning reflect increasing levels of sophisticated selection of variables on the case report form. As alluded to by Chalmers et al, there are several principles that can help guide clinical researchers to conduct efficient and high-quality studies17:

Build the CRF to align closely with the research design and develop and modify the protocol and template according to the feasibility of collecting data in clinical practice. The risk of designing a CRF after completing the research protocol is that some variables might not be feasible to collect as part of the clinical enterprise. The consequence of deviating from the protocol is the risk of compromised research quality. These findings further remind researchers to be certain to modify the CRF when the research protocol is modified.

Align the CRF with the research protocol. The variables in the CRF should be consistent with protocol. That is, all domains and variables mentioned in the protocol should be included in CRF to avoid missing any important domains or variables.

Develop the CRF to be concise and to the point. In general, variables only related to the study purpose could be included in the CRF. Unnecessary or redundant variables can require unnecessary time, effort collecting and monitoring. This can distract from limited time and energy of researchers to ensure the quality of key variables in clinical research. Berge et al also identify that data collection forms can be too complex and burden centres with a requirement to collect data items that are never analysed or reported.18

Refine the template to be readily understood and operational. In the final template of CRF, every variable should be clear. The structure and order of the CRF should be consistent with research flow and clinical practice.

These findings speak to fundamentals of conducting high-quality research, and while based on research in a single institution, can reasonably be expected to hold true in a broad range of settings. This is consistent with our research expectations.

A potential limitation of our study concerns the risk of selection bias of our sample. Clinician participants are from a premier academic hospital in Beijing, and these participants might have greater knowledge, cognitive skills and opportunities for research than clinicians in many other hospitals. We acknowledge the potential for variations on the findings in other settings while also acknowledging the results are genuine and representative of the participants’ experiences. Despite variations that exist in practice, we believe the lessons learned based on this study are transferable and robust ideas. Another potential limitation is that the interviewers were aware of the interviewed researchers’ experience and the study hypotheses, and this could raise concern about confirmation bias; however, the models were built and reviewed by the researchers themselves and this suggests that the processes delineated represent their views.

Further studies are needed to assess whether the approaches and variations described are robust across a wider variety of settings. The proposed expert model could be further validated by applying it to design of CRF for clinical research in different levels of hospitals and clinicians from other settings. Regardless, we believe that while there may be additional considerations, these findings are a robust and meaningful reference for any clinicians engaged in clinical research, and particularly, novice and moderately experienced researchers who wish to learn lessons from experts.

In conclusion, this research illustrates that increasing levels of sophistication in research planning reflect increasing levels of sophistication in the selection of variables for inclusion in a case report form. Thus, novice and intermediate-level clinical researchers alike could benefit by emulating the comprehensive planning procedures used by expert clinical researchers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate all the participants who made this research possible.

Footnotes

Contributors: HC and LZ conducted the interviews and all analyses, wrote the first draft of the manuscript and rewrote new drafts based on input from coauthors. MDF provided extensive input on the structuring of the manuscript and revisions of the manuscript drafts. YZ designed the research project, planned the analyses and provided input and revision of manuscript drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by grant 2013BAI09B14 from the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People’s Republic of China. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Peking University Third Hospital approved the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Original quotes and audio data of interviews are available on request by emailing the corresponding author. The presented data were anonymised and the risk of identification is low.

References

- 1. Zhao YM, Ding J, Zeng L. Top level design on clinical research. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2010;90:942–6. Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nahm M, Shepherd J, Buzenberg A, et al. . Design and implementation of an institutional case report form library. Clin Trials 2011;8:94–102. 10.1177/1740774510391916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cao AP, Bh S, Ding DY, et al. . The case report form in clinical research. Chin J Health Stat 2000:61–4. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fu HJ, Luo XX. [Key factors in design of case report form]. Yao Xue Xue Bao 2015;50:1452–5. Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Qn L, Lu F, Fh A, et al. . The design of case report form and analysis of common related problem. Chin J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2013:901–6. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 6. ST L. The design of case report form and its importance in drug clinical trials. Chin J New Drugs 2004:53–5. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xy L, Wen ZH, Tang XC, et al. . The principle and process of case report form design in clinical trials. Traditional Chinese Drug Research &Clinical Pharmacology, 2013:206–9. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lou H. The design and application of case report form in evidence-based traditional Chinese medicine research. Shandong Traditional Chinese Medicine University, 2015. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xy L, Zhang ZL, Yk A, et al. . Talking about the design of case report form from the point of data management. Modernization of traditional Chinese medicine and materia medica-world science and technology, 2014:614–7. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wan X, Yang H, Liu JP. The design of case report form in clinical research. J Traditional Chin Med 2007;10:885–7. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wang YH, Jiao YZ. The design of case report form and analysis of related problem in traditional Chinese medicine research. Chin J Traditional Chin Med and Pharm 2005;10:620–3. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meyer J. Qualitative research in health care. Using qualitative methods in health related action research. BMJ 2000;320:178–81. 10.1136/bmj.320.7228.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Devers KJ, Frankel RM. Study design in qualitative research-2: sampling and data collection strategies. Educ Health 2000;13:263–71. 10.1080/13576280050074543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kleijnen J, Chalmers I. How to practice and teach evidence-based medicine: role of the cochrane collaboration. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand Suppl 1997;111:231–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ioannidis JP, Greenland S, Hlatky MA, et al. . Increasing value and reducing waste in research design, conduct, and analysis. Lancet 2014;383:166–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62227-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, et al. . How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet 2014;383:156–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62229-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berge E, Al-Shahi Salman R, van der Worp HB, et al. . Increasing value and reducing waste in stroke research. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:399–408. 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30078-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.