Abstract

Background

Depression is associated with poor insulin sensitivity. We evaluated long-term effects of a cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) program for prevention of depression on insulin sensitivity in adolescents at risk for type 2 diabetes (T2D) with depressive symptoms.

Methods

One-hundred nineteen adolescent females with overweight/obesity, T2D family history, and mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms were randomized to a six-week CBT group (n=61) or six-week health education (HE) control group (n=58). At baseline, post-treatment, and one year, depressive symptoms were assessed, and whole body insulin sensitivity (WBISI) was estimated from oral glucose tolerance tests. Dual energy x-ray absorptiometry assessed fat mass at baseline and one year. Primary outcomes were one-year changes in depression and insulin sensitivity, adjusting for adiposity and other relevant covariates. Secondary outcomes were fasting and two-hour insulin and glucose. We also evaluated the moderating effects of baseline depressive symptom severity.

Results

Depressive symptoms decreased in both groups (P<0.001). Insulin sensitivity was stable in CBT and HE (ΔWBISI 0.1 vs. 0.3) and did not differ between groups (P=0.63). However, among girls with greater (moderate) baseline depressive symptoms (N=78), those in CBT developed lower 2-hour insulin than those in HE (Δ-16 vs. 16μIU/mL, P<.05). Additional metabolic benefits of CBT were seen for this subgroup in post-hoc analyses of post-treatment to one-year change.

Conclusions

Adolescent females at risk for T2D decreased depressive symptoms and stabilized insulin sensitivity one year following brief CBT or HE. Further studies are required to determine if adolescents with moderate depression show metabolic benefits after CBT.

Keywords: depression, child/adolescent, clinical trials, insulin resistance, T2D mellitus

There is mounting attention to the role of depressive symptoms in type 2 diabetes (T2D) risk and management (Thombs, 2014). Elevated depressive symptoms in adults with T2D are associated with future risk for poorer glycemic control, greater cognitive decline, and earlier mortality (Semenkovich, Brown, Svrakic, & Lustman, 2015). Randomized trials intervening on depression, either via behavioral or pharmacological approaches, in adults with T2D demonstrate remission in major depressive disorder (MDD) and depressive symptoms, but varied effects on glycemic control (Baumeister, Hutter, & Bengel, 2014).

Most studies of depression and T2D have involved adults, but adolescence may be a preferable age for intervention. Depressive symptoms increase during adolescence, primarily in girls (Hankin et al., 1998), as does puberty-related insulin resistance, which influences future progression to T2D (Goran, Shaibi, Weigensberg, Davis, & Cruz, 2006). Consistent with adult data (Yu, Zhang, Lu, & Fang, 2015), adolescent depressive symptoms correlate with poorer insulin sensitivity, independent of body composition, and predict worsening insulin sensitivity and T2D onset over time, irrespective of body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) or BMI gain (Shomaker & Goodman, 2015; Shomaker et al., 2011; Shomaker et al., 2010; Suglia, Demmer, Wahi, Keyes, & Koenen, 2016).

Therefore, we hypothesized that decreasing depressive symptoms during adolescence would prevent deterioration of insulin sensitivity in adolescents at risk for T2D. We conducted a randomized controlled trial (Shomaker et al., 2016) to determine if a six-session weekly cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) intervention designed to decrease depressive symptoms would prevent worsening of insulin sensitivity better than a health education (HE) standard-of-care control program among adolescent females at risk for T2D who also had symptoms of depression. A preliminary report of the immediate six-week post-intervention results showed that adolescents in both groups decreased depressive symptoms (Shomaker et al., 2016). Across groups, decreases in depressive symptoms were associated with improvements in insulin sensitivity. Among adolescents who had moderate (vs. mild) depressive symptoms, CBT produced greater decreases in depressive symptoms than HE. Insulin sensitivity remained stable in all participants during this short-term interval. In the current paper, we report changes in the primary efficacy outcome of insulin sensitivity over one year of follow-up. Adolescence is a dynamic period of the lifespan marked by major changes in social, psychological, neural, and biological domains (Steinberg, 2014). Previous longitudinal studies of this age group illustrate that depressive symptoms exert an effect on insulin resistance over the long-term (e.g., up to five years later), likely through a cascade of effects on stress-related behavior and physiology (Shomaker et al., 2011). In previous intervention studies, the impact of decreasing psychological symptoms on physical growth and endocrine outcomes frequently manifests to an increasingly greater extent as development unfolds over a longer-term follow-up interval, such as 1–3 years (versus directly after treatment) (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2016). We, therefore, anticipated that there would be more apparent metabolic benefits of CBT, compared to HE, over the longer one-year follow-up.

Meta-analyses have found that baseline level of depressive symptoms is a potent moderator of the immediate and longer-term effects of depression prevention programs (Stice, Shaw, Bohon, Marti, & Rohde, 2009). Therefore, we hypothesized that degree of depressive symptoms would moderate the treatment effect on insulin sensitivity, with adolescents who were more depressed at baseline demonstrating greater one-year metabolic benefits from CBT than those with mild symptoms.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

One-hundred nineteen 12–17y females were recruited for a T2D prevention trial (ClinicalTrials.gov ID NCT01425905) through mailings to area families, physician referrals, and posting of flyers. Participants had overweight or obesity (BMI≥85th percentile) and a family history of T2D, prediabetes, or gestational diabetes in at least one first- or second-degree relative. Adolescents were required to have mild-to-moderate symptoms of depression, indicated by a total score ≥16 on the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977), be in good general health, and have the ability to speak and understand English. Exclusion criteria were current psychiatric symptoms that necessitated treatment (e.g., MDD), major medical problem (e.g., T2D: fasting glucose >126 mg/dL or two-hour glucose >200 mg/dL), medication use affecting insulin, weight, or mood (e.g., anti-depressants), current involvement in structured weight loss or psychotherapy, and pregnancy. Informed consent and assent were obtained in writing from parents and adolescents, respectively, after the procedures were explained. The study was carried out in compliance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association and standards established by the Institutional Review Board of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, which approved all procedures. Adolescents were compensated for participation; transportation costs were covered for youth who could not otherwise participate.

Study Design

A parallel-group, randomized controlled trial was conducted to compare the effects of a CBT group with a HE standard-of-care control group (Shomaker et al., 2016). All components were carried out at the NIH Clinical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. Eleven cohorts of adolescents participated from September 2011–July 2014. After a baseline assessment to determine eligibility, participants were randomized to CBT or HE. Randomization, generated by an electronic program with permuted blocks, was stratified by age and race/ethnicity. Groups were run in parallel on weekdays after school, in separate clinics to deter cross-contamination. Follow-ups were completed at post-treatment and one year.

Experimental Groups

Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

The CBT group was a manualized depression prevention program consisting of one-hour sessions, once per week for six weeks (Stice, Rohde, Seeley, & Gau, 2008). On average, there were six adolescents in the CBT group per cohort (range = 3–8). The program has efficacy for decreasing adolescent depressive symptoms and reducing MDD onset, compared to assessment-only and active controls, for up to two years (Rohde, Stice, Shaw, & Briere, 2014; Stice, Rohde, Gau, & Wade, 2010; Stice et al., 2008). Stronger effects are observed in adolescents with baseline moderate, compared to mild, depressive symptoms (Muller, Rohde, Gau, & Stice, 2015).

Sessions were interactive, activity-based, and included motivational enhancement. Content included key CBT modules of psychoeducation about interconnectedness of feelings, thoughts, and behaviors, self-monitoring, self-reinforcement, positive self-statements, cognitive restructuring of negative thoughts, engagement in pleasant activities, and coping. Adolescents were assigned weekly homework to apply concepts learned in the sessions to their daily lives. The group was co-facilitated by one of six clinical psychologists and one of three clinical psychology doctoral students. Facilitators alternated between CBT and HE to control for possible therapist effects. Facilitators were trained by a program developer (ES). All sessions were audio-recorded so that therapists could receive ongoing, detailed weekly supervision from the lead psychologist (LS). In addition, a non-investigator program expert reviewed 20% of randomly selected audio-recordings and rated them for session fidelity and leader competence using the rating scales created by the developers of this program (Stice et al., 2008). With regard to fidelity, median ratings of CBT sessions were 7.7 on a scale ranging from 1 = none to 10 = perfect. With regard to therapist competence, median ratings of CBT sessions were 7.8 on a scale ranging from 1 = poor to 10 = superior. There was no crossover with HE identified in the taped sessions (Shomaker et al., 2016).

Health Education (HE)

The standard-of-care HE group was adapted from a didactic, middle- and high-school HE curriculum (“Hey-Durham;" Bravender, 2005). To match CBT for time and attention, the HE group met for one-hour sessions, once per week for six weeks. On average, there were five adolescents in the HE group per cohort (range = 3–9). The manualized curriculum covered education about substance use, nutrition, exercise, body image, domestic violence, conflict resolution, sun safety, and identifying depression and signs of suicide. The depression and suicide module focused on prevalence of these problems, their relation to other health issues, and how to identify warning signs. No direct personal counseling or advice was provided, other than in the event of a psychiatric crisis or suicidal ideation, in which case a treatment referral was facilitated.

Demographic and Medical Information

Parents reported adolescents’ age and race/ethnicity. A nurse practitioner or endocrinologist conducted a medical history and physical. Breast development was assessed by physical inspection and palpitation, and maturation was assigned according to the five Tanner stages (Marshall & Tanner, 1969).

Outcome Measures

All measurements were collected at baseline, repeated at an immediate post-treatment assessment and one year later. Assessors were blind to group assignment.

Anthropometrics

Participants in the fasted state removed shoes and outer clothing to be weighed to the nearest 0.1 kg with a digital scale. Height was determined with a wall stadiometer from the average of three measurements to the nearest millimeter. BMI (weight in kg/[height in m2]) and BMIz were calculated by CDC 2000 standards (Ogden et al., 2002).

Total fat mass (kg) was derived from dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (iDXA, GE Healthcare, Madison, WI) at baseline and one year.

Depressive Symptoms and Psychological Functioning

The total score of the 20-item CES-D was used to determine study inclusion (≥16) and to provide a continuous measure of depressive symptoms (Radloff, 1977). We categorized participants as those with mild symptoms (total score=16–20) and those with moderate depressive symptoms (>20) (Stockings et al., 2015). To determine presence of MDD or another psychiatric disorder in the past year, the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS; Kaufman et al., 1997) was administered to adolescents by a trained interviewer. The K-SADS has adequate test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and predictive validity in adolescents (Nolen-Hoeksema, Stice, Wade, & Bohon, 2007), and in this sample, demonstrated good inter-rater reliability for MDD (k=0.89 on 20% of interviews).

Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (OGTT)

An OGTT was performed in the morning following an overnight fast initiated at 10:00 pm the previous evening. Participants received 1.75 g/kg of dextrose (maximum 75 g). Blood was sampled for serum insulin and plasma glucose at fasting and at 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes after dextrose. Insulin and glucose were determined using standard methods as previously reported (Shomaker et al., 2016). Whole body insulin sensitivity index (WBISI) was calculated as 10,000 divided by the square root of the product of fasting glucose (mg/dL) and fasting insulin (mIU/mL) times the product of mean glucose0–120 (mg/dL) and mean insulin0–120 (mIU/mL). WBISI has been validated against clamp-derived measures (Yeckel et al., 2004). Higher WBISI values represent better insulin sensitivity and lower values represent poorer insulin sensitivity. Change in WBISI over one year was the primary outcome. As secondary measures, we evaluated fasting insulin and glucose, two-hour insulin and glucose, and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR). Higher HOMA-IR values reflect worse insulin resistance and lower values reflect little to no insulin resistance.

Statistical Methods

A planned sample of 58 per group, allowing for 30% attrition, provided 80% power using a two-sided α level of 0.05 to detect a moderate effect (0.54 SD) in the primary one-year outcome of insulin sensitivity. Analyses were conducted with SPSS 23 (IBM, 2015) and SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Incorporated, 2011). The intent-to-treat sample consisted of participants who were randomized, regardless of whether they withdrew or were excluded after randomization. A priori, individuals who developed an exclusion criterion, including pregnancy, medication use (e.g., stimulants, anti-depressants, or insulin sensitizers), or regular psychotherapy, were withdrawn during the follow-up phase, so that any observed effects were not confounded by these variables. The intent-to-treat sample included the data from these participants to the point at which they were withdrawn, and missing data were imputed. Binary logistic regression was used to evaluate baseline predictors of one-year attrition. ANCOVAs were conducted to characterize one-year change from baseline in depressive symptoms, BMI (kg/m2), and fat mass (kg) by group. In these models, we adjusted for baseline depressive symptoms, BMI or fat mass, and time to follow-up, baseline age, pubertal status, degree of diabetes family history, race/ethnicity, and group facilitator. We also accounted for baseline BMIz in models predicting change in depressive symptoms and fat mass. Parallel ANCOVAs were conducted with the primary outcome of one-year insulin sensitivity change as the dependent variable and group as the independent variable. Covariates included baseline insulin sensitivity, baseline fat mass, baseline to post-treatment fat mass change, time to follow-up, baseline BMIz, age, pubertal status, diabetes family history, race/ethnicity, and facilitator. Parallel ANCOVAs evaluated secondary outcomes of changes in HOMA-IR, fasting and two-hour insulin and glucose. Multiple imputation using Monte Carlo Markov chain method in SAS PROC MI with 20 imputed data sets was used to handle missing data. We also conducted analyses with complete data using listwise deletion. Analyses were conducted for the entire sample and for the subset with baseline moderate depressive symptoms, because this subset had greater post-treatment decreases directly after CBT versus HE (Shomaker et al., 2016). As post-hoc analyses, we evaluated metabolic change during the follow-up period, by predicting changes from post-treatment to one-year. This approach addresses metabolic improvement/deterioration during the maintenance phase following the intervention (Eakin et al., 2014).

RESULTS

In the total sample (Table 1), baseline BMI and BMIz were lower in CBT than HE (P<0.05), with no other differences (Ps>0.10). Sixty-six percent (n=78) of the sample had moderate baseline depressive symptoms. Similar percentages with moderate depressive symptoms were randomized to CBT (68.9%) and HE (62.1%; P=0.44). Overall, adolescents with moderate depressive symptoms were older (15.2±1.5y versus 14.6±1.6y, P=0.03) than those with milder symptoms, but did not differ in other characteristics. Among the subset with baseline moderate depressive symptoms, there were no differences between those in CBT versus HE (Ps>0.06).

Table 1.

Descriptive baseline information by group assignment, for the total sample and for adolescent females with moderate depressive symptoms

| Characteristic | Total Sample | Moderate Depressive Symptoms† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBT | HE | CBT | HE | |

| n | 61 | 58 | 42 | 36 |

| Age, y+ | 15.0 ± 1.6 | 15.1 ± 1.6 | 15.2 ± 1.5 | 15.3 ± 1.5 |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 39 (63.9) | 35 (60.3) | 27 (64.3) | 23 (63.9) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 8 (13.1) | 11 (19.0) | 7 (16.7) | 7 (19.4) |

| Hispanic | 7 (11.5) | 5 (10.3) | 5 (11.9) | 2 (5.6) |

| Other | 7 (11.5) | 6 (10.3) | 3 (7.1) | 4 (11.1) |

| Tanner breast stage, n (%) | ||||

| 1–2 | 2 (3.3) | 2 (3.4) | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.8) |

| 3 | 7 (11.4) | 4 (6.9) | 3 (7.2) | 2 (5.6) |

| 4 | 7 (11.5) | 13 (22.4) | 5 (11.9) | 6 (16.7) |

| 5 | 45 (73.8) | 39 (67.2) | 32 (76.2) | 27 (75.0) |

| BMI, kg/m2+ | 31.7 ± 6.1 | 34.4 ± 7.3 | 32.2 ± 6.5 | 34.7 ± 6.5 |

| BMIz+ | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.4 |

| % Body fat+ | 40.8 ± 5.4 | 42.5 ± 6.0 | 40.7 ± 5.5 | 42.6 ± 5.9 |

| Depressive symptoms+ | 25.3 ± 7.3 | 24.5 ± 7.5 | 28.7 ± 6.2 | 28.4 ± 7.1 |

| Hba1c, %+ | 5.3 ± 0.4 | 5.3 ± 0.3 | 5.4 ± 0.3 | 5.4 ± 0.3 |

| WBISI+ | 2.7 ± 1.7 | 2.3 ± 1.4 | 2.7 ± 1.8 | 2.5 ± 1.4 |

| HOMA-IR+ | 5.3 ± 4.3 | 7.1 ± 7.4 | 5.5 ± 4.8 | 6.2 ± 5.2 |

| Fasting insulin, μIU/mL+ | 23.9 ± 18.6 | 30.6 ± 27.5 | 24.9 ± 20.9 | 27.4 ± 21.1 |

| Two-hour insulin, μIU/mL+ | 147.1 ± 131.8 | 131.0 ± 129.7 | 131.3 ± 127.6 | 137.4 ± 123.8 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL+ | 88.6 ± 6.7 | 89.7 ± 7.6 | 88.1 ± 7.0 | 89.6 ± 6.7 |

| Two-hour glucose, mg/dL+ | 102.8 ± 21.0 | 105.9 ± 22.4 | 101.3 ± 19.7 | 108.0 ± 23.3 |

Moderate Depressive Symptoms refer to a Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale total score >20.

Mean (standard deviation). CBT is cognitive-behavioral group. HE is health education group. WBISI is whole body insulin sensitivity index, with higher values reflecting better insulin sensitivity and lower values poorer insulin sensitivity. HOMA-IR is homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance, with higher values representing greater insulin resistance and lower values little to no insulin resistance. Hba1c refers to glycated hemoglobin.

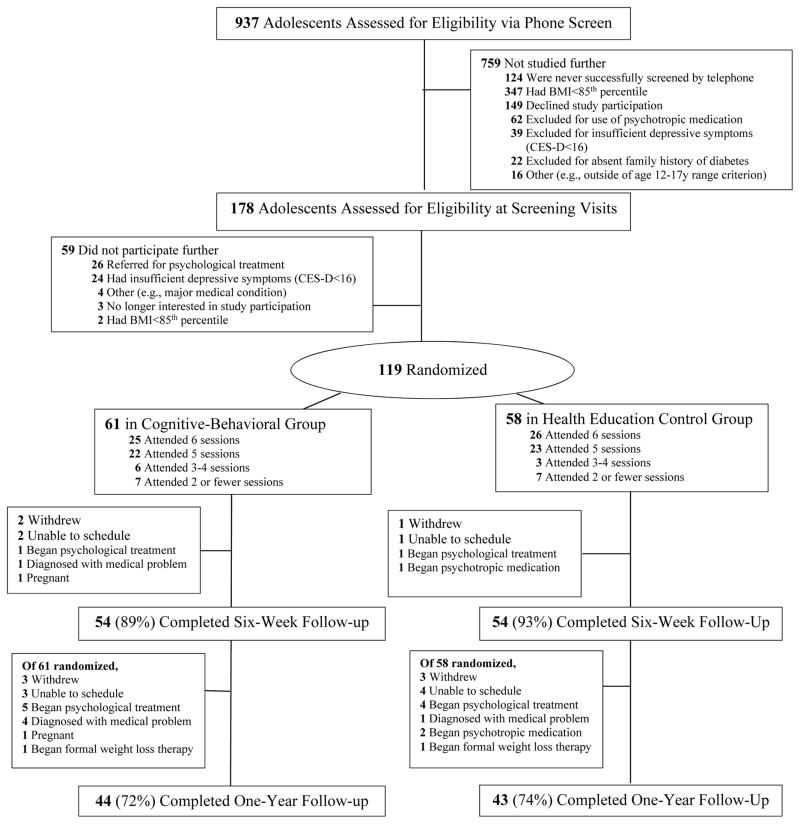

Study flow is displayed in Figure 1. Program attendance was high; in CBT, 80% (n=49) and in HE, 79% (n=46) of adolescents attended at least five (80%) of six sessions (P=0.89). Seventy-two percent in CBT (n=44) and 74% (n=43) in HE completed a one-year follow-up (P=0.81). Dropouts were more likely to have been in early/mid-puberty (Tanner 2–3) than late puberty (Tanner 4–5) at baseline (OR=8.49, 95%CI=2.07 to 34.74, P=0.003), with no other differences (Ps>0.21).

Figure 1.

Study flow from initial assessment to one-year follow-up; six-week follow-up, immediate post-treatment results have been published elsewhere (11).

Depressive Symptoms

Full sample

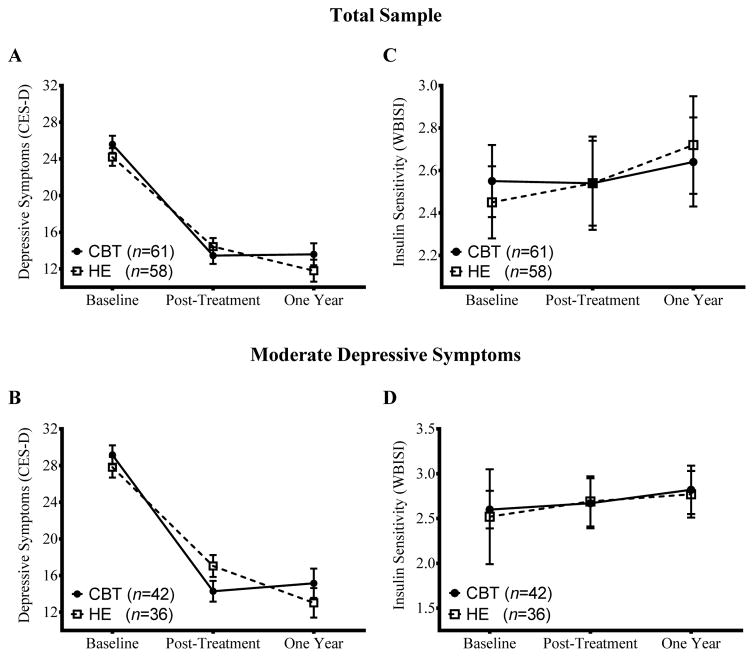

At one-year, few adolescents developed MDD in either group (CBT: 3.3%, n=2 versus HE: 1.7%, n=1, P=0.59). Another 11 adolescents (CBT: 8.2%, n=5 versus HE: 10.3%, n=6, P=0.69) were withdrawn because they started a psychotropic medication (e.g., anti-depressant) or initiated regular psychotherapy. Adjusting for covariates, adolescents in CBT and HE both had significant decreases (Ps<0.001) in depressive symptoms from baseline to one year (ΔMean±SE, CBT:Δ−12.0±1.2 versus HE:Δ −12.4±1.2, P=0.81). Figure 2A depicts the course of depressive symptoms over the study.

Figure 2.

Time course over the study of adolescent depressive symptoms, as assessed on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D), and of whole body insulin sensitivity (WBISI), with greater values reflecting better insulin sensitivity and lower values reflecting poorer insulin sensitivity. Panels A and C characterize the total sample; panels B and D describe the subset with baseline moderate depressive symptoms (CES-D >20) only. Values displayed are derived from multiply imputed data and are adjusted for covariates.

Sample subset

Among adolescents with baseline moderate depressive symptoms, all participants decreased depressive symptoms from baseline to one year (P<0.001), with no group difference (CBT:Δ −14.0±1.6 versus HE:Δ −14.8±1.6, P=0.72; Figure 2B).

BMI and Adiposity

Full sample

Accounting for covariates, BMI change from baseline to one year did not differ between groups (CBT:Δ0.7±0.3 kg/m2 versus HE:Δ0.9±0.3 kg/m2, P=0.61). There was no group effect on body fat (CBT:Δ1.9±0.6 kg versus HE:Δ2.1±0.6 kg, P=0.83).

Sample subset

Among adolescents with baseline moderate depressive symptoms, there was no group effect on baseline to one-year BMI change (CBT:Δ0.6±0.4 versus HE:Δ0.8±0.4, P=0.78). Likewise, there was no difference in one-year body fat change (CBT:Δ1.8±0.7 versus HE:Δ1.7±0.7, P=0.90).

Insulin Sensitivity and Other Indices

Full sample

One teen (HE) developed criteria for T2D and was referred to their physician for follow-up. Table 2 displays results for baseline to one-year change in insulin sensitivity and other indices. There was no group effect on insulin sensitivity (P=0.54) or any secondary index (Ps>0.18). At one year, insulin sensitivity showed within-group stability in CBT and HE (Figure 3C), as did all other metabolic indicators (Ps>0.12).

Table 2.

Summary of group condition effects on changes in one-year outcomes from baseline, for the total sample and for females with moderate depressive symptoms at baseline

| Changes from Baseline Values at One Year in Total Sample | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Multiple Imputation | Completers | |||||||

|

|

||||||||

| CBT‡ (n=61) | HE‡ (n=58) | Group Effect+ | P | CBT‡ (n=37–43) | HE‡ (n=33–42) | Group Effect+ | P | |

| WBISI | 0.09 (−0.34, 0.52) | 0.27 (−0.19, 0.74) | −0.18 ± 0.30 | 0.54 | −0.13 (−0.58, 0.33) | 0.22 (−0.24, 0.68) | −0.35 ± 0.29 | 0.24 |

| HOMA-IR | −0.34 (−1.18, 0.49) | −0.20 (−1.07, 0.67) | −0.14 ± 0.61 | 0.81 | −0.36 (−1.29, 0.58) | −0.36 (−1.30, 0.59) | 0.003 ± 0.60 | 0.99 |

| Fasting insulin, μIU/mL | −1.60 (−4.96, 1.75) | −0.63 (−4.22, 2.95) | −0.97 ± 2.45 | 0.69 | −1.66 (−5.43, 2.11) | −1.18 (−5.01, 2.65) | −0.48 ± 2.41 | 0.84 |

| Two-hour insulin, μIU/mL | −7.79 (−26.47, 10.90) | 8.63 (−11.41, 28.66) | −16.41 ± 13.47 | 0.22 | −3.96 (−25.54, 17.62) | 9.97 (−12.28, 32.22) | −13.93 ± 13.38 | 0.30 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 0.22 (−1.89, 2.34) | −1.51 (−3.43, 0.40) | 1.74 ± 4.26 | 0.18 | 0.44 (−1.72, 2.60) | −1.57 (−3.74, 0.61) | 2.01 ± 1.33 | 0.14 |

| Two-hour glucose, mg/dL | 3.67 (−2.48, 9.83) | 0.78 (−5.67, 7.22) | 2.90 ± 4.13 | 0.48 | 4.13 (−2.65, 10.91) | 0.31 (−6.79, 7.40) | 3.82 ± 4.21 | 0.37 |

|

|

||||||||

| Changes from Baseline Values at One Year in Participants with Moderate Depressive Symptoms† | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Multiple Imputation | Completers | |||||||

|

|

||||||||

| CBT‡ (n=42) | HE‡ (n=36) | Group Effect+ | P | CBT‡ (n=26–31) | HE‡ (n=20–25) | Group Effect+ | P | |

| WBISI | 0.22 (−0.33, 0.77) | 0.25 (−0.28, 0.78) | −0.03 ± 0.35 | 0.93 | 0.13 (−0.43, 0.68) | 0.44 (−0.11, 0.99) | −0.31 ± 0.35 | 0.38 |

| HOMA-IR | −0.84 (−1.88, 0.20) | −0.03 (−1.03, 0.96) | −0.81 ± 0.55 | 0.24 | −1.19 (−2.24, −0.14) | −0.68 (−1.75, 0.39) | −0.51 ± 0.67 | 0.45 |

| Fasting insulin, μIU/mL | −3.52 (−7.79, 0.74) | −0.30 (−4.39, 3.79) | −3.22 ± 2.83 | 0.25 | −4.98 (−9.25, −0.71) | −2.84 (−7.20, 1.52) | −2.14 ± 2.72 | 0.44 |

| Two-hour insulin, μIU/mL | −16.30 (−39.61, 7.01) | 16.21 (−8.55, 40.98) | −32.52 ± 16.30 | 0.048 | −14.87 (−40.99, 11.26) | 25.14 (−2.74, 53.02) | −40.01 ± 16.32 | 0.02 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | −0.34 (−2.82, 2.14) | −0.60 (−3.04, 1.83) | 0.26 ± 1.68 | 0.62 | −0.74 (−3.61, 2.12) | −0.88 (−3.81, 2.05) | 0.14 ± 1.78 | 0.94 |

| Two-hour glucose, mg/dL | −0.28 (−7.71, 7.16) | 3.11 (−4.40, 10.61) | −3.38 ± 5.06 | 0.50 | −3.37 (−11.28, 4.54) | 1.17 (−7.22, 9.55) | −4.54 ± 4.91 | 0.36 |

Mean (95% CI).

CB-HE (Mean ± standard error).

Moderate Depressive Symptoms refer to participants whose Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale total score was >20 at baseline. CBT is cognitive-behavioral group. HE is health education group. WBISI is whole body insulin sensitivity index. HOMA-IR is homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance. All estimates are adjusted for the outcome value at baseline, baseline and ones-year change in fat mass, baseline BMIz, baseline age, baseline puberty, family history of diabetes, race/ethnicity, facilitator, and time to follow-up.

Subset with Moderate Depression

In adolescents with baseline moderate depressive symptoms, there was no group difference in insulin sensitivity (P=0.93; Figure 3D). There was a group effect on two-hour insulin. Participants in CBT had a greater decrease in two-hour insulin from baseline to one year than HE (Group effect Δ −32.5±16.3 μIU/mL, P=0.048, Cohen’s d=0.51). The same pattern was observed in analyses with completer data (Δ −40.0±16.3 μIU/mL, P=0.019, Cohen’s d=0.64).

Post-hoc Analyses of Metabolic Maintenance

Full sample

There were no effects of condition on insulin sensitivity or secondary outcomes (Ps>0.05).

Subset with Moderate Depression

In adolescents with baseline moderate depressive symptoms, the group effect on insulin sensitivity did not reach significance (Group effect Δ0.56±0.33, P=0.09, Cohen’s d=0.35; Table 3). In analyses with completer data, there was a group effect on insulin sensitivity (Δ0.80±0.31, P=0.02, Cohen’s d=0.56). Adolescents in CBT showed post-treatment to one-year stability in insulin sensitivity (ΔWBISI=0.08, 95%CI: −.38 to 0.54), whereas those in HE showed deterioration (ΔWBISI=−0.72, 95%CI: −1.31 to −0.13).

Table 3.

Summary of group condition effects on maintenance changes in one-year outcomes from post-treatment, for the total sample and for girls with moderate depressive symptoms at baseline

| Changes from Post-Treatment to One Year in Total Sample | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Multiple Imputation | Completers | |||||||

|

|

||||||||

| CBT‡ (n=61) | HE‡ (n=58) | Group Effect+ | P | CBT‡ (n=34–41) | HE‡ (n=27–41) | Group Effect+ | P | |

| WBISI | 0.11 (−0.30, 0.53) | −0.14 (−0.62, 0.32) | 0.26 ± 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.13 (−0.26, 0.51) | −0.29 (−0.72, .015) | 0.41 ± 0.30 | 0.17 |

| HOMA-IR | −0.66 (−1.52, 0.20) | −0.57 (−1.51, 0.36) | −0.09 ± 0.58 | 0.88 | −0.54 (−1.30, 0.23) | −0.41 (−1.26, 0.45) | −0.13 ± 0.58 | 0.82 |

| Fasting insulin, μIU/mL | −2.47 (−6.26, 1.31) | −0.81 (−5.03, 3.41) | −1.66 ± 2.92 | 0.57 | −2.32 (−5.55, 0.91) | −1.75 (−5.36, 1.86) | −0.57 ± 2.46 | 0.82 |

| Two-hour insulin, μIU/mL | −6.11 (−28.45, 16.23) | 25.94 (0.11, 51.77) | −32.05 ± 17.95 | 0.08 | −5.19 (−28.79, 18.41) | 26.65 (−.12, 53.43) | −31.84 ± 18.16 | 0.09 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 0.47 (−1.73, 2.66) | −0.69 (−2.90, 1.51) | 1.16 ± 1.47 | 0.43 | 0.40 (−1.58, 2.38) | −1.11 (−3.10, 0.87) | 1.51 ± 1.42 | 0.29 |

| Two-hour glucose, mg/dL | −0.28 (−5.35, 4.80) | 0.94 (−5.14, 7.03) | −1.22 ± 4.12 | 0.77 | 0.16 (−5.12, 5.45) | −0.38 (−5.89, 5.13) | 0.54 ± 3.90 | 0.89 |

|

|

||||||||

| Changes from Post-Treatment to One Year in Participants with Moderate Depressive Symptoms† | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Multiple Imputation | Completers | |||||||

|

|

||||||||

| CBT‡ (n=42) | HE‡ (n=36) | Group Effect+ | P | CBT‡ (n=24–40) | HE‡ (n=15–24) | Group Effect+ | P | |

| WBISI | 0.16 (−0.30, 0.62) | −0.39 (−0.89, 0.10) | 0.56 ± 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.08 (−0.38, 0.54) | −0.72 (−1.31, −0.13) | 0.80 ± 0.31 | 0.02 |

| HOMA-IR | −0.94 (−1.95, 0.07) | −0.07 (−1.09, 0.95) | −0.87 ± 0.65 | 0.18 | −1.44 (−2.44, −0.43) | −0.31 (−1.49, 0.87) | −1.13 ± 0.64 | 0.09 |

| Fasting insulin, μIU/mL | −3.95 (−8.08, 0.18) | 2.94 (−2.28, 8.16) | −6.89 ± 3.49 | 0.048 | −6.33 (−10.61, −2.04) | −1.66 (−6.67, 3.36) | −4.67 ± 2.71 | 0.09 |

| Two-hour insulin, μIU/mL | −11.53 (−38.21, 15.16) | 38.01 (6.84, 69.17) | −50.56 ± 21.76 | 0.02 | −11.06 (−44.93, 22.82) | 56.37 (14.39, 98.34) | −67.43 ± 22.70 | 0.01 |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dL | 0.29 (−2.27, 2.86) | 0.53 (−2.36, 3.41) | −0.23 ± 1.77 | 0.90 | −1.49 (−4.44, 1.45) | −0.83 (−3.91, 2.27) | −0.67 ± 1.86 | 0.72 |

| Two-hour glucose, mg/dL | −2.95 (−9.18, 3.28) | 2.78 (−4.46, 10.01) | −5.73 ± 4.68 | 0.22 | −5.22 (−12.42, 1.98) | −0.28 (−8.60, 8.03) | −4.94 ± 4.71 | 0.30 |

Mean (95% CI).

Mean ± standard error.

Moderate Depressive Symptoms refer to participants whose Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale total score was >20 at baseline. CBT is cognitive-behavioral group. HE is health education group. WBISI is whole body insulin sensitivity index. HOMA-IR is homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance. All estimates are adjusted for the outcome value at post-treatment, baseline and one-year change in fat mass, baseline BMIz, baseline age, baseline puberty, family history of diabetes, race/ethnicity, facilitator, and time to follow-up.

For secondary outcomes, there was a group effect on post-treatment to one-year change in fasting insulin. Adolescents in CBT showed a pattern toward decreased fasting insulin, and those in HE had no change (Group effect Δ −6.89±3.49 μIU/mL, P=0.048, Cohen’s d=0.43). This effect became marginal (P=0.09) in completer analyses. There also was a group effect on post-treatment to one-year change in two-hour insulin. CBT had no change, whereas HE showed increases in two-hour insulin (Group effect Δ −50.6±21.8 μIU/mL, P=0.02, Cohen’s d=0.61). This effect was more pronounced in completer analyses (Group effect Δ −67.43±22.70 μIU/mL, P=0.006, Cohen’s d=0.94).

DISCUSSION

The objective of this randomized controlled trial was to test if deterioration in insulin sensitivity could be prevented by directly intervening with depressive symptoms in adolescent girls at risk for T2D with mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms. Following participation in either a six-week cognitive behavioral (CBT) depression prevention group or a six-week health education (HE) control group, adolescents in both conditions had decreases in depressive symptoms and stable insulin sensitivity one year later, with no differences between groups. In a subset analysis of those with greater (i.e., moderate) depressive symptoms at baseline, adolescents randomized to CBT had greater declines in two-hour insulin at one year than did adolescents randomized to HE.

Among those with moderate baseline depressive symptoms, CBT participants had greater acute decreases in depressive symptoms than HE (Shomaker et al., 2016). Yet, there was no difference between CBT and HE in one-year depressive symptoms, regardless of initial symptom severity. CBT and HE were matched for time, intensity, delivery mode, and facilitator expertise. CBT provides psychoeducation on depression, teaches tools to restructure negative thoughts, and encourages behavioral activation; yet, both conditions were delivered in a group format with same-sex peers, under the supervision of a psychologist, lending themselves to some degree of non-specific social support in both contexts. Consistent with this explanation, past investigations of CBT depression prevention were less robust for decreasing depressive symptoms when compared to an active control such as a supportive-expressive group over a 6-month or longer follow-up (Rohde et al., 2014; Stice et al., 2010; Stice et al., 2008). A similar pattern of more rapid change, with equivocal longer-term outcomes in depressive symptoms, has been observed with other therapeutic modalities for depression prevention (e.g., interpersonal psychotherapy) when compared to an active control (Young, Mufson, & Gallop, 2010). Without an assessment-only condition, it is not possible to determine whether participation in CBT and HE caused the decreases that were observed in depressive symptoms at one year, or whether the changes reflect regression to the mean. In addition, we may not have had adequate power to detect an effect on one-year change in depressive symptoms among the subset of more depressed adolescents.

Insulin sensitivity was stable following CBT and HE. This pattern is notable given that deterioration in insulin sensitivity would be expected in adolescents at risk for T2D (Goran et al., 2006; Shomaker & Goodman, 2015). We cannot rule out that overall stabilization of insulin sensitivity occurred because of other variables. For instance, it is possible that completion of pubertal development could explain the stabilization observed in insulin sensitivity (Moran et al., 1999), despite the gains in adiposity observed in the cohort.

Because of the heterogeneity in depressive symptoms in this sample, and evidence of greater decreases in symptoms in CBT versus HE participants at posttest for those with initially higher baseline depressive symptoms (Shomaker et al., 2016), we evaluated the group effect on metabolic outcomes in the sample subset with baseline moderate depressive symptoms. Adolescents with moderate depressive symptoms at baseline had lower two-hour insulin at one year in CBT compared to HE. This finding was consistent in multiply imputed and complete data, and represented a medium effect size. When we explored, in post-hoc analyses, changes in metabolic outcomes over the maintenance interval, adolescents with baseline moderate depressive symptoms in CBT had better fasting and two-hour insulin from post-treatment to one year than HE. Although fasting and two-hour insulin were secondary metabolic outcomes, these indices have been identified as two of the most salient, early markers of T2D and cardiovascular disease risk in youth (Libman et al., 2010). Using complete data, adolescents with baseline moderate depression symptoms in CBT had stable insulin sensitivity, whereas those in HE showed deterioration in insulin sensitivity during the follow-up interval. These subgroup analyses require replication with an adequately powered sample of adolescents with moderate depressive symptoms. These preliminary findings raise the possibility that a stand-alone treatment for mental health could have a sustained impact on metabolic trajectories, but additional studies are required.

The explanatory mechanisms by which CBT potentially led to improvements in one-year insulin outcomes in adolescents with moderate depressive symptoms remain unclear, but are of great interest. Of note, we accounted for initial adiposity and change in adiposity, indicating that the observed effects were not explained merely by the relationships of depressive symptoms and insulin to adiposity. If addressing depressive symptoms lessens the risk of developing T2D, even without inducing weight loss, this would have significant implications for preventative medicine. Theoretically, stress-related behaviors and physiology may underlie the direct connection between depression and insulin resistance. Decreasing depressive symptoms acutely may lead, over time, to subsequent changes in stress mechanisms, which in turn ameliorate insulin resistance as adolescents develop (Shomaker et al., 2016). In particular, potentially contributing stress-related behavioral factors, including disinhibited eating (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2012), sleep disturbance (Depner, Stothard, & Wright, 2014), infrequent moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and habitual sedentary time (Berman, Weigensberg, & Spruijt-Metz, 2012; Poitras et al., 2016), require exploration in future studies. Likewise, stress-related physiological factors that have been associated with depressive symptoms and diabetes risk, such as hypercortisolism and a proinflammatory imbalance (Adam et al., 2010), may be explanatory and should be evaluated in future studies as possible mediating mechanisms.

Strengths of this study include the randomized controlled trial design, use of an active control, reliable and validated measures, and focus on a novel, targeted approach to prevention of T2D in adolescents at risk for this chronic disease. Power was adequate for the full sample and one-year retention was good. Yet, group effects were only observed in a subset with baseline moderate depressive symptoms, and as a consequence, these analyses were not adequately powered. The total number of analyses increases odds of chance effects, despite the a priori nature of the aims. Generalizability is limited by the specific selection criteria, including adolescent girls with overweight/obesity, a family diabetes history, and mild-to-moderate depressive symptoms. Most of the sample was non-Hispanic Black/African American, reflecting the demographic of the study’s geographic area. Caution should be exercised in generalizing the findings to males or other race/ethnicities. The study design involved withdrawal during the follow-up of subjects who developed an exclusion criterion, including the initiation of medication or regular therapy. Although this strategy minimized the confounding influence of these factors on treatment outcomes and missing data were handled with multiple imputation, it contributed to a more incomplete follow-up and could have led to biased estimates (in either direction). Despite the high insulin resistance of this cohort, only one adolescent converted to T2D over one year, suggesting that an even longer-term follow-up to capture possible differences in deterioration of insulin sensitivity and in the emergence, or prevention, of early-onset T2D would be valuable.

The dramatic increase in prevalence of early-onset T2D, particularly in girls and in disadvantaged racial/ethnic groups (Dabelea et al., 2014), calls for novel approaches to T2D prevention. If a relatively brief, six-week/six-hour psychosocial intervention impacts diabetes risk, it would offer the potential of a cost-effective, targeted, preventative approach in high-risk youth. Additional studies are essential to test whether brief CBT programs can improve insulin action and secretion in adolescents at high-risk for depression and diabetes in the long term, and to determine the mechanisms of action.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Author contributions: LBS, MT-K, and JAY designed the study and obtained grants to fund the study. LBS and CO conducted the statistical analyses. LBS wrote the manuscript. LBS, NRK, RMR, and OLC facilitated intervention groups. LBS, NRK, RMR, OLC, and LMS conducted clinical interviews and assessments. JAY, SMB, and APD performed physical examinations and conducted medical histories. KYC oversaw body composition measurements. ES developed the experimental intervention, trained the facilitators, and consulted on recruitment and study design. MT-K, JAY, CO, NRK, RMR, OLC, LMS, SMB, APD, KYC and ES reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the interpretation of findings. Funding sources: This study was supported by K99HD069516 and R00HD069516 (LBS) from NICHD, NIH Intramural Research Program Grant 1ZIAHD000641 (JAY) from NICHD with supplemental funding from the NIH Bench to Bedside Program (LBS, MT-K, JAY), Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (JAY), and the NIH Office of Disease Prevention (JAY).

Footnotes

Clinical trial reg. no: NCT01425905, clinicaltrials.gov

References

- Adam TC, Hasson RE, Ventura EE, Toledo-Corral C, Le KA, Mahurkar S, … Goran MI. Cortisol is negatively associated with insulin sensitivity in overweight Latino youth. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2010;95(10):4729–4735. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister H, Hutter N, Bengel J. Psychological and pharmacological interventions for depression in patients with diabetes mellitus: an abridged Cochrane review. Diabetes Medicine. 2014;31:773–786. doi: 10.1111/dme.12452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman LJ, Weigensberg MJ, Spruijt-Metz D. Physical activity is related to insulin sensitivity in children and adolescents, independent of adiposity: a review of the literature. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 2012;28(5):395–408. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravender T. Health, Education, and Youth in Durham: HEY-Durham Curricular Guide. 2. Durham, NC: Duke University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dabelea D, Mayer-Davis EJ, Saydah S, Imperatore G, Linder B, Divers J … Search for Diabetes in Youth Study. Prevalence of type 1 and type 2 diabetes among children and adolescents from 2001 to 2009. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;311(17):1778–1786. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depner CM, Stothard ER, Wright KP., Jr Metabolic consequences of sleep and circadian disorders. Current Diabetes Reports. 2014;14:507. doi: 10.1007/s11892-014-0507-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eakin EG, Winkler EA, Dunstan DW, Healy GN, Owen N, Marshall AM, … Reeves MM. Living well with diabetes: 24-month outcomes from a randomized trial of telephone-delivered weight loss and physical activity intervention to improve glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(8):2177–2185. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goran MI, Shaibi GQ, Weigensberg MJ, Davis JN, Cruz ML. Deterioration of insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function in overweight Hispanic children during pubertal transition: a longitudinal assessment. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity. 2006;1(3):139–145. doi: 10.1080/17477160600780423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107(1):128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, … Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36(7):980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libman IM, Barinas-Mitchell E, Bartucci A, Chaves-Gnecco D, Robertson R, Arslanian S. Fasting and 2-hour plasma glucose and insulin: relationship with risk factors for cardiovascular disease in overweight nondiabetic children. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(12):2674–2676. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Archives of Disorders of Childhood. 1969;44:291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran A, Jacobs DR, Jr, Steinberger J, Hong CP, Prineas R, Luepker R, Sinaiko AR. Insulin resistance during puberty: results from clamp studies in 357 children. Diabetes. 1999;48(10):2039–2044. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.10.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller S, Rohde P, Gau JM, Stice E. Moderators of the effects of indicated group and bibliotherapy cognitive behavioral depression prevention programs on adolescents’ depressive symptoms and depressive disorder onset. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2015;75:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Stice E, Wade E, Bohon C. Reciprocal relations between rumination and bulimic, substance abuse, and depressive symptoms in female adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2007;116(1):198–207. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Guo S, Wei R, … Johnson CL. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: Improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):45–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poitras VJ, Gray CE, Borghese MM, Carson V, Chaput JP, Janssen I, … Tremblay MS. Relationships between objectively measured physical activity and health indicators in school-aged children and youth: 845 Board #161 June 1, 3: 30 PM – 5: 00 PM. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2016;48(5 Suppl 1):235–236. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000485708.08247.c9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychology Measures. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rohde P, Stice E, Shaw H, Briere FN. Indicated cognitive behavioral group depression prevention compared to bibliotherapy and brochure control: acute effects of an effectiveness trial with adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014;82(1):65–74. doi: 10.1037/a0034640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semenkovich K, Brown ME, Svrakic DM, Lustman PJ. Depression in type 2 diabetes mellitus: prevalence, impact, and treatment. Drugs. 2015;75:577–587. doi: 10.1007/s40265-015-0347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomaker LB, Goodman E. An 8-year prospective study of depressive symptoms and change in insulin from adolescence to young adulthood. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2015;77(8):938–945. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomaker LB, Kelly NR, Pickworth CK, Cassidy OL, Radin RM, Shank LM, … Yanovski JA. A randomized controlled trial to prevent depression and ameliorate insulin resistance in adolescent girls at-risk for type 2 diabetes. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2016;50(5):762–774. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9801-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Stern EA, Miller R, Zocca JM, Field SE, … Yanovski JA. Longitudinal study of depressive symptoms and progression of insulin resistance in youth at risk for adult obesity. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(11):2458–2463. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Young-Hyman D, Han JC, Yanoff LB, Brady SM, … Yanovski JA. Psychological symptoms and insulin sensitivity in adolescents. Pediatric Diabetes. 2010;11(6):417–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Age of opportunity: lessons from the new science of adolescence. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Rohde P, Gau JM, Wade E. Efficacy trial of a brief cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program for high-risk adolescents: effects at 1- and 2-year follow-up. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(6):856–867. doi: 10.1037/a0020544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Gau JM. Brief cognitive-behavioral depression prevention program outperforms two alternative interventions: a randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(4):595–606. doi: 10.1037/a0012645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Shaw H, Bohon C, Marti CN, Rohde P. A meta-analytic review of depression prevention programs for children and adolescents: factors that predict magnitude of intervention effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(3):486–503. doi: 10.1037/a0015168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockings E, Degenhardt L, Lee YY, Mihalopoulos C, Liu A, Hobbs M, Patton G. Symptom screening scales for detecting major depressive disorder in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of reliability, validity and diagnostic utility. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2015;174:447–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suglia SF, Demmer RT, Wahi R, Keyes KM, Koenen KC. Depressive symptoms during adolescence and young adulthood and the development of type 2 diabetes mellitus. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2016;183(4):269–276. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Stern EA, Miller R, Sebring N, Dellavalle D, … Yanovski JA. Children’s binge eating and development of metabolic syndrome. International Journal of Obesity. 2012;36(7):956–962. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Wilfley DE, Young JF, Sbrocco T, Stephens M, … Yanovski JA. Excess weight gain prevention in adolescents: three-year outcome following a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2016 doi: 10.1037/ccp0000153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thombs BD. Routine depression screening for patients with diabetes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2014;312(22):2412–2413. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeckel CW, Weiss R, Dziura J, Taksali SE, Dufour S, Burgert TS, … Caprio S. Validation of insulin sensitivity indices from oral glucose tolerance test parameters in obese children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2004;89(3):1096–1101. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JF, Mufson L, Gallop R. Preventing depression: a randomized trial of interpersonal psychotherapy-adolescent skills training. Depression and Anxiety. 2010;27(5):426–433. doi: 10.1002/da.20664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M, Zhang X, Lu F, Fang L. Depression and risk for diabetes: a meta-analysis. Canadian Journal of Diabetes. 2015;39(4):266–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjd.2014.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]