Abstract

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs), a main source of type I interferon in response to viral infection, are an early cell target during lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) infection, which has been associated with the LCMV’s ability to establish chronic infections. Human blood-derived pDCs have been reported to be refractory to ex vivo LCMV infection. In the present study we show that human pDC CAL-1 cells are refractory to infection with cell-free LCMV, but highly susceptible to infection with recombinant LCMVs carrying the surface glycoprotein of VSV, indicating that LCMV infection of CAL-1 cells is restricted at the cell entry step. Co-culture of uninfected CAL-1 cells with LCMV-infected HEK293 cells enabled LCMV to infect CAL-1 cells. This cell-to-cell spread required direct cell-cell contact and did not involve exosome pathway. Our findings indicate the presence of a novel entry pathway utilized by LCMV to infect pDC.

Keywords: arenavirus, LCMV, pDC, cell-to-cell spread, cell-cell contact

INTRODUCTION

Several arenaviruses, chiefly Lassa virus (LASV) in West Africa, cause hemorrhagic fever (HF) disease in humans and pose important public health problems within their endemic regions (Bray, 2005; Buchmeier et al., 2007; Geisbert and Jahrling, 2004). Additionally, mounting evidence indicates that the worldwide-distributed prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) is a neglected human pathogen of clinical significance (Barton and Mets, 1999, 2001; Barton et al., 2002; Fischer et al., 2006; Jahrling and Peters, 1992; Mets et al., 2000). Concerns about human pathogenic arenaviruses are exacerbated as there are no FDA-licensed arenavirus vaccines (Olschlager and Flatz, 2013) and current anti-arenaviral therapy is limited to off-label use of ribavirin that is only partially effective (Bausch et al., 2010; Damonte and Coto, 2002; Hadi et al., 2010). Evidence indicates that morbidity and mortality associated with LASV, as well as other human pathogenic arenaviruses, involves a failure of the host’s innate immune response to restrict virus replication and to facilitate the initiation of an effective adaptive immune response (McCormick and Fisher-Hoch, 2002).

Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) are a distinct DC population that is specialized in the production of type I interferon (IFN-I), and have been shown to play critical roles in the host response to infection and associated pathogenesis, as well as in autoimmune diseases (Swiecki and Colonna, 2015; Wang et al., 2011). pDCs sense phagocytosed RNA and DNA viruses through the endosomal pattern recognition receptor (PRR) toll-like receptor 7 (TLR-7) and 9 (TLR-9), respectively, and produce a high level of IFN-I, thus contributing to the establishment of IFN-I-mediated antiviral defense (Gilliet et al., 2008). pDCs can also detect replicating RNA viruses via a cytosolic PRR, named retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) (Kumagai et al., 2009). Prompt and robust IFN-I secretion by pDCs is critical for controlling the virus multiplication at early times of infection, and can dictate the outcome of infection and associated disease. Accordingly, LCMV infection of its natural host the mouse, results in induction of IFN-I production at early time times after infection (Jung et al., 2008; Zuniga et al., 2008). Intriguingly, and in contrast to other viral infections, production of high levels of IFN-I at the early stages of LCMV infection seems to play a pro-viral role and promote the establishment of a chronic infection by the immunosuppressive strain clone 13 (Cl-13) of LCMV, as the blockade of IFN-I signaling results in the early clearance of Cl-13 (Teijaro et al., 2013). High number of splenic pDCs are infected at early times following intravenous (i.v.) infection of mice with a high dose of the persistent strain Cl-13, but not with Armstrong (ARM) strain that causes an acute infection that is controlled and cleared from most tissues within two weeks. This suggests that the magnitude of pDC infection may contribute to LCMV’s ability to cause an acute or chronic infection (Bergthaler et al., 2010; Macal et al., 2012). Human blood derived pDCs have been shown to sense LCMV in neighboring-infected non-pDC cells, a process likely mediated by virus RNA-containing exosomes without productive LCMV infection of pDCs (Wieland et al., 2014). These findings indicated that pDCs can produce high levels of IFN-I in response to cytosolic virus replication or neighboring infected cells via exosomes, or both. Despite the key roles played by pDCs in IFN-I production during arenavirus infection, there is only limited information about the mechanisms whereby arenaviruses infect pDCs, and a detailed understanding of this process might facilitate the development of novel strategies to combat human pathogenic arenaviruses. The relatively low numbers of human pDCs circulating in blood poses technical complications to studies aimed at investigating the mechanisms of LCMV infection of human pDCs. To overcome this problem we took advantage of a human pDC cell line, CAL-1, established from a lymphoma patient, which has been shown to express a set of cell surface proteins characteristic of pDC (Maeda et al., 2005), and produces TNF-α and IFN-α in response to TLR-7 (Hilbert et al., 2015) and TLR-9 (Steinhagen et al., 2013) ligand stimulations. Here, we demonstrate that as with human blood-derived pDCs, CAL-1 cells are also refractory to infection with both Cl-13 and ARM, whereas recombinant LCMVs carrying the surface glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) efficiently infected CAL-1 cells, indicating that infection of CAL-1 cells is restricted at the step of cell entry. Notably, CAL-1 cells become susceptible to LCMVs when co-cultured with LCMV-infected cells. This cell-to-cell spread required direct cell-cell contact and did not involve the exosome pathway. Our findings indicate that LCMV utilizes an alternative cell entry pathway for pDC infection that may contribute to arenavirus dissemination and pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells

CAL-1 cells were grown in RPMI medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin at 37°C and 5% CO2. 293T cells were grown in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin at 37°C and 5% CO2. HEK293 cells constitutively expressing RFP (293-RFP) (GenTrget Inc) were grown in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin and 10 μg/ml of blasticidin at 37°C and 5% CO2. Vero E6 cells (ATCC CRL-1586) were grown in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 100 U/ml penicillin at 37°C and 5% CO2

Generation of rLCMVs

Recombinant Armstrong (rARM) and clone-13 (rCl-13) strains of LCMV were generated as described (Emonet et al., 2009; Flatz et al., 2006; Sanchez and de la Torre, 2006). rLCMVs expressing the surface glycoprotein from Lassa virus (rCl-13/LASV-GPC), live attenuated Candid#1 vaccine strain of JUNV (rCl-13/JUNV-GPC), or VSV (rCl-13/VSV-G) were generated by reverse genetics using procedures similar to those described for the generation of rARM/LASV-GPC (Rojek et al., 2008) and rARM/JUNV-GPC (Iwasaki et al., 2013).

Virus titration

LCMV titers were determined using an immunofocus forming assay (IFFA) as described (Battegay, 1993). Briefly, 10-fold serial virus dilutions were used to infect Vero cell monolayers in a 96-well plate and at 20 h p.i., cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. After cell permeabilization by treatment with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS containing 3% BSA, cells were stained with a rat monoclonal antibody (mAb) to NP (VL-4, Bio X Cell) conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Protein Labeling Kit, Life Technologies) (VL-4-AF488).

Infection of CAL-1 cells with cell-free rLCMVs

CAL-1 cells (1 × 106) were infected with rLCMVs (moi = 1) at 37°C and 5% CO2. After a 1 h adsorption period, cells were washed with PBS, re-suspended in 5 ml of fresh medium, and cultured in a T25 flask at 37°C and 5% CO2. At the indicated h p.i., cells were fixed with 4% PFA in PBS, permeabilized by Perm/Wash Buffer (BD Biosciences), stained with VL-4-AF488, and NP-expression analyzed by flow cytometry.

Co-culture of CAL-1 cells with rLCMV-infected 293-RFP cells separated by transwell membrane

293-RFP cells (5 × 105 cell/well) were seeded on transwell membrane (Corning) with a pore size of 0.4 μm (top well) (6-well format) and cultured overnight, followed by infection (moi = 0.1) with rLCMVs. After overnight incubation at 37°C and 5% CO2, CAL-1 cells (5 × 105 cell/well) were added to the bottom side of the transwell and 72 h later CAL-1 cells were collected, fixed with 4% PFA in PBS, stained with VL-4-AF488, and NP expression was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Production of infectious rLCMV progeny

CAL-1 cells were infected (moi = 1) with rLCMVs and seeded (1 × 105 cells/well) in a 24-well plate. At the indicated times after infection, cell culture samples were collected, centrifuged at 400 g and 4°C for 10 min, and viral titers in the supernatant were determined by IFFA.

Flow cytometry for detection of CAL-1 cells expressing LCMV NP

rLCMV-infected cells were fixed with 4% PFA in PBS, permeabilized by Perm/Wash Buffer and stained with VL-4-AF488. Flow-cytometric analysis was performed using a BD LSR II (Becton Dickson) and data were analyzed using FlowJo (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR). For co-culture experiments, the red fluorescent-positive population (293-RFP cells) was excluded for the analysis to determine numbers of LCMV-infected CAL-1 cells.

Detection of glycosylated αDG

CAL-1 and 293T cells (1 × 106 cells) were fixed with 4% FPA in PBS, incubated with primary mouse mAb IIH6 (IgM) that recognizes fully glycosylated αDG (Ervasti and Campbell, 1993; Michele et al., 2002) followed by incubation with secondary anti-mouse IgM antibody conjugated with PE, and αDG expression analyzed by flow cytometry. For some samples, primary antibody was omitted for negative controls.

Detection of production of bio-active IFN-I in tissue culture supernatants (TCS)

Vero E6 cells were treated with the indicated TCS for 16 h followed by infection with rNDV-eGFP (Martinez-Sobrido et al., 2006) (moi = 0.1). At 24 h p.i. with rNDV-eGFP, cells were fixed and numbers of GFP + cells determined by epifluorescence. Nuclei were visualized by DAPI staining. Four independent fields (30 to 100 cells/field) were inspected and the % of GFP + cells (average/field +/− SD) determined.

RESULTS

Susceptibility of CAL-1 cells to infection with cell-free LCMV

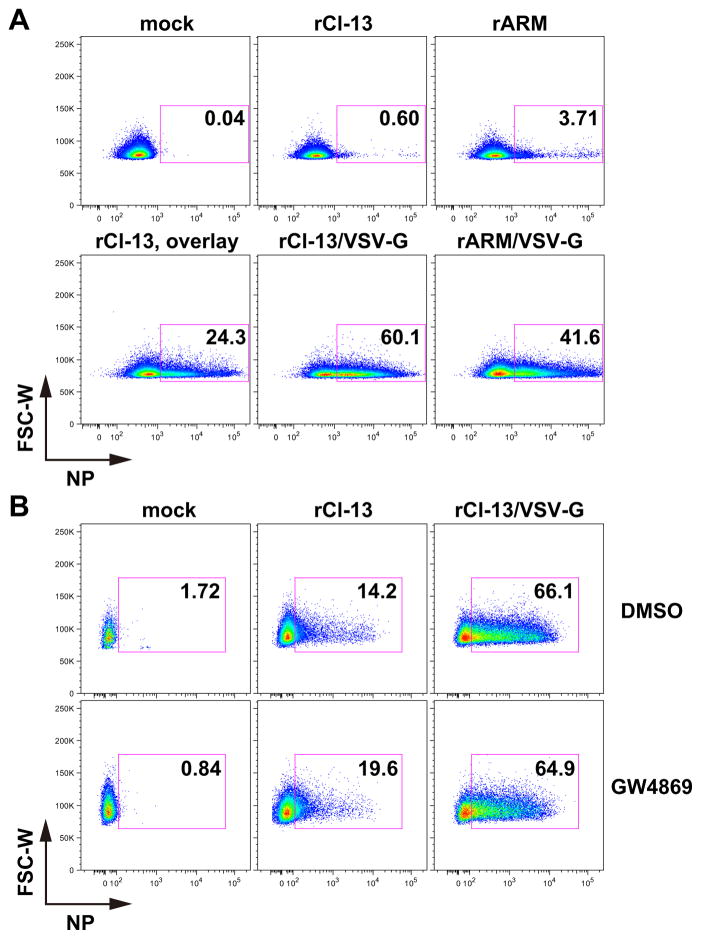

To examine whether CAL-1 cells were refractory to LCMV infection and whether this restriction was due to a blockade of LCMV glycoprotein-mediated cell entry, we infected CAL-1 cells with a series of rLCMVs expressing their authentic surface glycoproteins, or the one from VSV (VSV-G). We observed negligible numbers of CAL-1 cells infected with rCl-13 or rARM (Fig. 1A). In contrast, rCl-13/VSV-G and rARM/VSV-G efficiently infected CAL-1 cells, indicating that cell entry of LCMV is restricted in CAL-1 cells. Similarly, very low numbers of cells infected with rCl-13 encoding the GPC of LASV (rCl-13/LASV-GPC) were NP positive, whereas rCl-13 expressing the GPC from the genetically distantly related New World (NW) arenavirus JUNV (rCl-13/JUNV-GPV), which uses the ubiquitously expressed human transferrin receptor as an entry receptor (Radoshitzky et al., 2007), efficiently infected CAL-1 cells. We next asked whether CAL-1 cells could support a productive life cycle of LCMV infection after the virus had entered the cells. For this, we infected CAL-1 cells with rCl-13, rARM, or rCl-13/VSV-G and examined NP-positive cell populations every 24 h after infection. Consistent with our previous results, we observed negligible numbers of NP-positive cells in either rCl-13- or rARM-infected CAL-1 cells (Fig. 1B). In contrast, we observed increasing numbers of NP-positive CAL-1 cells were observed over time following their infection with rCl-13/VSV-G. Accordingly, virus titers in tissue culture supernatant (TCS) of rCl-13- or rARM-infected CAL-1 cells were two to three logs lower than those of rCl-13/VSVG-infected, indicating that CAL-1 cells are able to function as a cell substrate to complete all the steps of the virus life cycle except for the cell entry step (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1. CAL-1 cells are refractory to LCMV GPC-mediated cell entry.

(A) CAL-1 cells are refractory to wild type rLCMVs. CAL-1 cells were infected (moi = 1) with indicated rLCMVs. At 72 h p.i., cells were collected, fixed with 4% PFA in PBS and NP-positive cells analyzed by flow cytometry. (B) Virus spread in CAL-1 cells. CAL-1 cells were infected (moi = 1) with indicated rLCMVs. At indicated times of p.i., cells were collected, fixed with 4% PFA in PBS and NP-positive cells analyzed by flow cytometry. (C) Production of infectious progenies from CAL-1 cells infected with rLCMVs. CAL-1 cells were infected (moi = 1) with indicated rLCMVs. At several time points as indicated, TCS were collected and virus titers determined by IFFA. Data represent means ± SD of three independent experiments.

Co-culture of CAL-1 cells with LCMV-infected cells

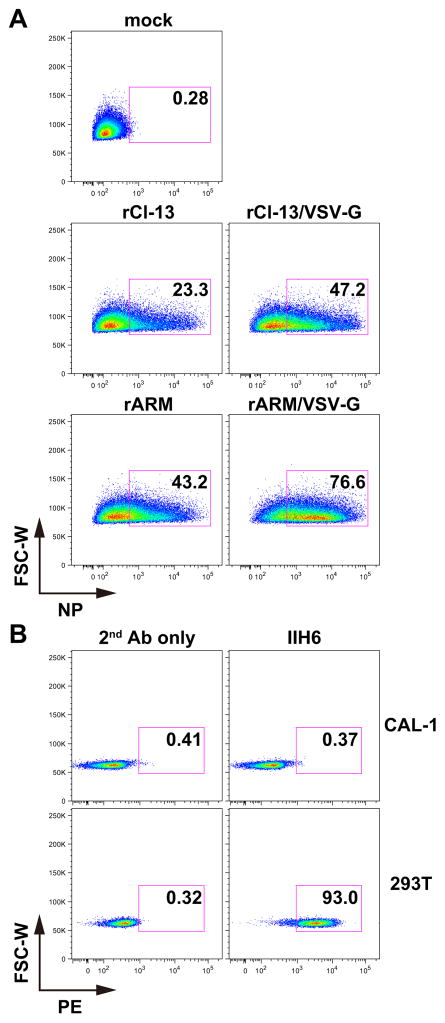

Evidence indicates that LCMV can infect pDCs in vivo (Bergthaler et al., 2010; Macal et al., 2012), which appears to be in conflict with our findings. These conflicting observations could be reconciled by hypothesizing that pDC infection with LCMV may require the interaction of uninfected pDCs with infected neighboring non-pDCs that facilitate transfer of virus to uninfected pDCs. To test this hypothesis, we infected 293-RFP cells with rLCMVs and 20 hours later, co-cultured LCMV-infected 293-RFP cells with CAL-1 cells for 72 hours. Consistent with our previous findings using cell-free virus for infection, co-culture of CAL-1 cells with rCl-13/VSV-G or rARM/VSV-G infected 293-RFP resulted in high numbers of infected CAL-1 cells (Fig. 2A). Unexpectedly, a high number of CAL-1 cells co-cultured with rCl-13- or rARM-infected 293-RFP cells were NP-positive, indicating that LCMV can be transmitted to pDCs from infected neighboring non-pDCs (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. CAL-1 cells became susceptible to rLCMVs when co-cultured with LCMV-infected 293-RFP cells.

(A) LCMV transmission from rLCMV-infected 293-RFP cells to CAL-1 cells. 293-RFP cells seeded in a T25 flask at 1 × 106 cells/flask and cultured overnight were infected (moi = 0.1) with indicated rLCMVs. At 24 h p.i., CAL-1 cells (1 × 106) were added to the LCMV-infected 293-RFP cells. 72 h later, floating cells were harvested and NP expression analyzed by flow cytometry. RFP-positive cell population (293-RFP cells) was excluded from the data. (B) CAL-1 cells do not express fully glycosylated αDG. CAL-1 and 293T cells were fixed with 4% PFA in PBS, incubated with anti-αDG antibody (IIH6) followed by incubation with anti-mouse IgM antibody conjugated with PE, and αDG expression analyzed by flow cytometry. For some samples, the primary antibody was omitted to serve as negative controls.

We next asked whether alpha-dystroglycan (αDG), a cell entry receptor used by LASV and Cl-13, but not ARM, strain of LCMV (Cao et al., 1998), was involved in this cell-to-cell spread. We anticipated this to be unlikely since rCl-13 and rARM, which have high and low affinity to αDG (Kunz et al., 2001; Sullivan et al., 2011), respectively, were efficiently transmitted to CAL-1 cells. Consistent with our prediction, we observed that cell surface expression of fully glycosylayted αDG in CAL-1 cells was below levels detectable by flow cytometry, whereas consistent with a previous report fully glycosylated αDG was readily detected at the surface of 293T cells (Oppliger et al., 2016) (Fig. 2B). Therefore, it is highly unlikely that αDG was involved in this cell-to-cell spread.

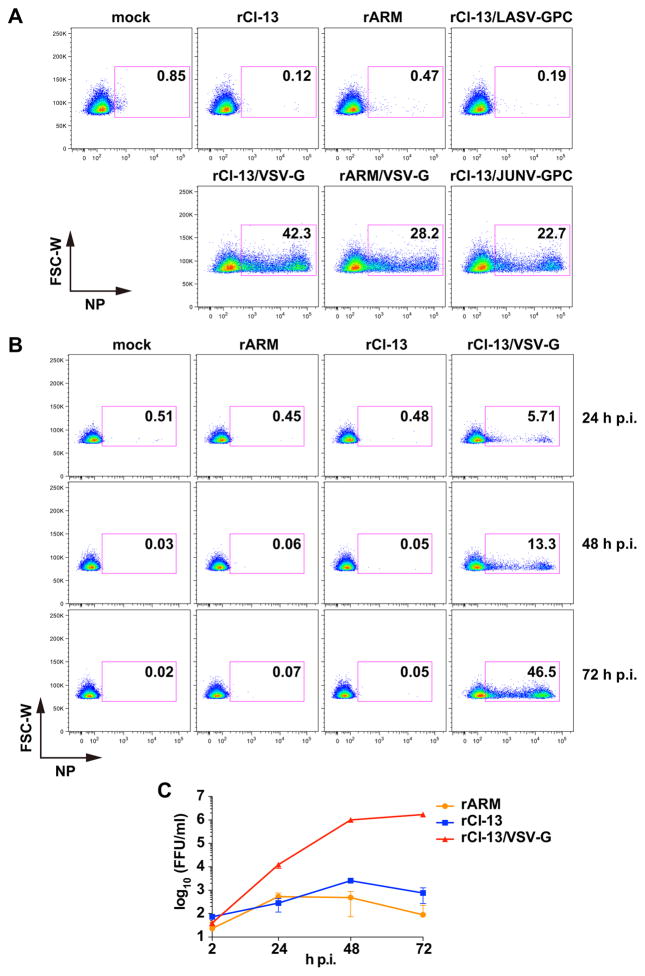

Contribution of the exosome pathway to LCMV cell-to-cell spread

Exosomes are small (40–100 nm in diameter) membrane vesicles generated by inward budding of endosomal membrane into multivesicular bodies (MVBs) (Mittelbrunn and Sanchez-Madrid, 2012; Raposo and Stoorvogel, 2013; Thery et al., 2009). Exosomes pooled in MVBs are then released into the extracellular space by membrane fusion between MVBs and the plasma membrane. Exosomes are known to transfer virus RNAs and proteins to neighboring cells modulating the immune state of the recipient cells (Dreux et al., 2012; Fleming et al., 2014; Pleet et al., 2016). We therefore examined whether the exosome pathway was involved in cell-to-cell spread of LCMV. For this, we seeded 293-RFP cells on the top well of a transwell system and infected them with rLCMVs. The next day we added CAL-1 cells to the bottom well and co-cultured them for three days. In this system, the membrane pore size (0.4 μm) was selected such that cell-free virus particles and exosomes, but not cells, could go through the pores. Consistent with our results using cell-free virus infections (Fig. 1A), rCl-13/VSV-G and rARM/VSV-G produced by infected 293-RFP cells diffused through the membrane pores and efficiently infected CAL-1 cells (Fig. 3A). Co-culture of CAL-1 cells (bottom well) with LCMV-infected 293-RFP cells (top well) resulted only in very low numbers of NP-positive CAL-1 cells (Fig. 3A), while LCMV was transmitted very efficiently to CAL-1 cells in the absence of transwell (Fig. 3A, overlay). Under these experimental conditions, co-culture with LCMV, either rCl-13- or rARM, infected cells resulted in slightly higher frequency of NP positive CAL-1 cells (< 4%) compared to cell-free virus infection (<1%). These modest differences likely reflected the continuous supply of progeny virus derived from rLCMV-infected cells on the top well, which could partially counteract the very inefficient infection of CAL-1 cells, whereas in the case of cell-free virus infection CAL-1 cells were exposed to infectious virus particles only at the beginning of the infection. The continuous supply of progeny virus may have contributed to increased numbers of NP positive CAL-1 cells during transwell co-cultures with either rCl-13/VSV-G- or rARM/VSV-G-infected 293-RFP cells. We observed that neither rCl-13 nor rARM was efficiently transmitted from infected 293-RFP cells to CAL-1 cells separated by a transwell membrane with a pore size that allowed exosomes to go across. However, it was plausible that exosomes played a role in LCMV cell-to-cell spread only when both cells were in very close proximity. To address this possibility, we examined the effect of pharmacological inhibition of exosome production on LCMV cell-to-cell spread. For this we infected 293-RFP cells with the indicated rLCMVs. At 16 h p.i. cells were washed and treated with the exosome inhibitor, GW4869, followed by addition of CAL-1 and co-culture for three days. GW4869 treatment did not significantly reduce the numbers of CAL-1 NP-positive cells following co-culture with 293-RFP cells infected with either rCl-13 or rCl-13/VSV-G (Fig. 3B). We observed similar results in rARM infection (not shown). Collectively, these findings indicated that cell-to-cell spread of LCMV from 293-RFP cells to CAL-1 cells requires direct cell-cell contact, but without the participation of the exosome pathway.

Figure 3. Cell-to-cell spread of LCMV requires direct cell-cell contact.

(A) Direct interaction with rLCMV-infected 293-RFP cells is required for infection of CAL-1 cells with rLCMV. 293-RFP cells seeded on transwell membrane (top well) and cultured overnight were infected (moi = 0.1) with indicated rLCMVs. At 24 h p.i., CAL-1 cells were added to each bottom well. As a positive control, CAL-1 cells were added onto 293-RFP cells infected with rCl-13 (overlay). 72 h later, CAL-1 cells were harvested from bottom wells, fixed with 4% PFA in PBS, stained with VL-4-AF488, and NP expression analyzed by flow cytometry. RFP-positive (293-RFP) cells were excluded from the data. (B) An exosome inhibitor, GW4869, does not prevent infection of CAL-1 cells through direct interaction with rLCMV-infected cells. 293-RFP cells seeded (1 × 105 cells/well) in a 12-well plate and cultured overnight were infected (moi = 0.1) with indicated rLCMVs. At 24 h p.i., rLCMV-infected 293-RFP cells were treated with GW4869 (10 μM) for 2 h and then CAL-1 cells (2 × 105 cells/well) were added onto the LCMV-infected 293-RFP cells. GW4869 was present in culture medium throughout the end of the experiment. 72 h later, floating cells were harvested, fixed with 4% PFA in PBS, and stained with VL-4-AF488, and NP expression analyzed by flow cytometry. RFP-positive cell population (293-RFP cells) was excluded from the data.

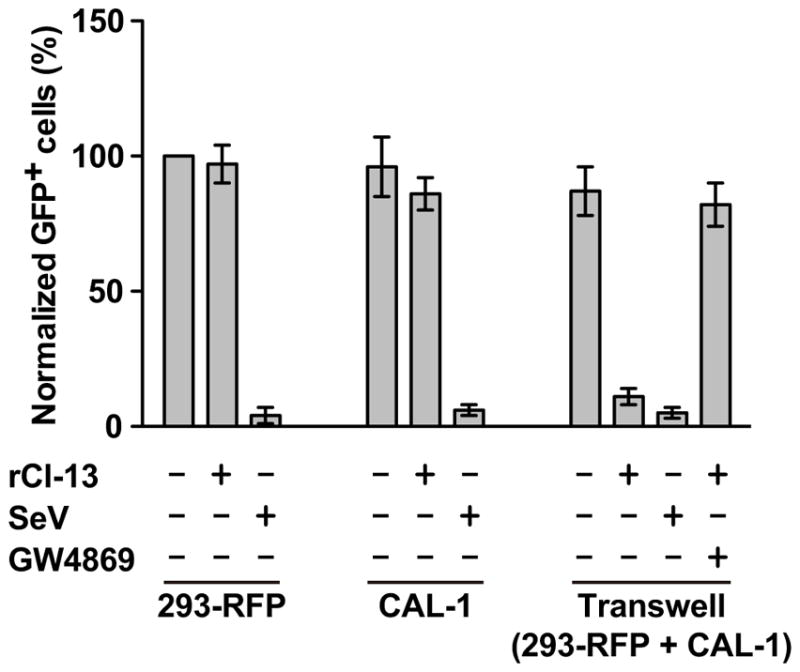

Consistent with previous findings we observed that CAL-1 cells were able to produce bioactive IFN-I upon co-culture with LCMV-infected 293-RFP cells, and that this process depended on an active exosome pathway (Fig 4).

Figure 4. Production of bio-active IFN-I by CAL-1 cells co-cultured with LCMV-infected 293-RFP cells.

Single cell cultures of 293-RFP or CAL-1 cells, as well as transwell co-cultures of CAL-1 and 293-RFP cells were infected with either SeV (Martinez-Sobrido et al., 2006) or rCl-13 and 24 h later TCS collected, UV treated to inactivate virus and used to treat Vero cell monolayers for 16 h, followed by infection with rNDV-GFP. At 24 h p.i. with rNDV-GFP cells were fixed and numbers of GFP + cells determined and normalized as described in Materials and Methods section. Transwell co-cultures were also treated with the exosome inhibitor GW4869.

DISCUSSION

Virus infections of humans, in most cases, begin with exposure of susceptible cells to cell-free virus. Once the virus replicates within the initial target cells and assembles all the components necessary to reinitiate productive infection, the virus fundamentally has two exit strategies to disseminate in the infected host. Those two modes of dissemination are 1) diffusion of cell-free virus and 2) cell-to-cell spread. Several enveloped viruses including flavivirus, herpesviruses, paramyxoviruses, poxvirus, retroviruses, and rhabdovirus have been reported to utilize both modes of disseminations (Gross and Thoma-Kress, 2016; Sattentau, 2008; Singh et al., 2016; Zhong et al., 2013). In the present study, we have demonstrated that cell-free preparations of the prototypic arenavirus LCMV were unable to infect human pDC CAL-1 cells. However, upon co-culture with LCMV-infected 293-RFP, CAL-1 cells became readily infected with LCMV, and this virus transfer was abrogated using transwell co-culture conditions. Our results from co-culture studies using transwell filter inserts with a pore size of 0.4 μm do not provide a formal final proof of the need for direct contact between CAL-1 cells and LCMV-infected 293-RFP cells to allow infection of CAL-1 cells. However, the inability of cell-free LCMV to infect CAL-1 cells together with the observation that the exosome pathway was not involve in the transfer of LCMV from infected 293-RFP to CAL-1 under co-culture conditions, strongly suggest that the most likely mechanism involved in this virus transfer is cell-to-cell contact.

As with many other viruses, arenaviruses have means to counteract the host innate immune responses, and accordingly the arenavirus NP (Martinez-Sobrido et al., 2006; Rodrigo et al., 2012) and Z protein (Fan et al., 2010; Xing et al., 2015) have been reported to efficiently block IFN-I induction in infected cells. However, LCMV infection of mice results in a robust IFN-I production at early times during the course of infection, but there are still many unanswered questions about the cellular sources and mechanisms whereby LCMV infection triggers induction of IFN-I in mice. We have shown that exposure of blood-derived human pDCs to cell-free LCMV does not result in production of detectable levels of IFN-α or LCMV infection, but these human pDCs produced high levels of IFN-α upon sensing neighboring LCMV-infected cells through a TLR7-dependent, virus-independent, exosomal RNA transfer mechanism without a need for a productive infection of pDCs (Wieland et al., 2014). Intriguingly, LCMV-mediated induction of IFN-I by pDCs and LCMV infection of pDCs differ in their dependence on the activity of the exosome pathway. It is plausible that IFN-I may be secreted from uninfected pDCs activated by sensing virus RNA transmitted via exosomes released from LCMV-infected cells present in close proximity to pDCs. In contrast, infection of pDCs via cell-to-cell contact with neighboring LCMV-infected cells is an exosome-independent process, and induction of IFN-I in these LCMV-infected pDCs might be suppressed by the reported IFN-antagonistic activities of arenavirus NP and Z protein (Fan et al., 2010; Martinez-Sobrido et al., 2006; Rodrigo et al., 2012; Xing et al., 2015).

αDG was identified as a cell entry receptor for Old World arenaviruses including LCMV and LASV and clade C New World arenaviruses (Cao et al., 1998; Spiropoulou et al., 2002). To function as an entry receptor for arenaviruses αDG needs to undergo complex post-translational modifications including O-glycosylation, in which LARGE (glycosyltransferase like-acetylglucosaminyltransferase) plays a critical role (Imperiali et al., 2005; Inamori et al., 2012; Kunz et al., 2005). A single amino acid mutation in GP1 from 260F (ARM) to 260L (Cl-13) changes GP1 affinity from low (ARM) to high (Cl-13) affinity for αDG that is expressed at high levels in CD11c positive splenic DCs in mice (Kunz et al., 2001; Sevilla et al., 2000). Mutation F260L in GP1 together with K1079Q mutation in the virus L polymerase has been shown to increase the Cl-13’s ability to infect DCs, which has been implicated in Cl-13 persistence by establishing an immune environment beneficial for long-term virus infection (Sevilla et al., 2000). CAL-1 cells did not express detectable level of fully glycosylated αDG. We attempted to restore αDG expression in CAL-1 cells by transducing them with an adenovirus vector expressing DG. However, we were unable to detect αDG expression by flow cytometry using IIH6 antibody, which can recognize fully glycosylated αDG (Ervasti and Campbell, 1993; Michele et al., 2002), while we confirmed that CAL-1 cells were susceptible to transduction by an adenovirus vector expressing GPF. It is plausible that CAL-1 cells lack expression of LARGE, required to generate fully glycosylated αDG. The lack of αDG expression in CAL-1 cells raises the possibility of the existence of an as-yet-unidentified receptor involved in cell-to-cell spread of LCMV into pDCs, and its identification might uncover ways to disrupt arenavirus spread within the pDC population as a novel therapeutic approach to combat arenavirus infections.

Several proposed mechanisms of cell-to-cell viral spread includes 1) fusion of cell plasma membranes, 2) generation of a bridge (protrusion) or tunnel (nanotube) structure by rearrangement of cytoskeleton, on or in which virions can travel from an infected cell to target cell, and 3) use of structures characteristic for polarized epithelial cells (tight junctions) or neuronal cells (neural synapses) (Sattentau, 2008; Zhong et al., 2013). Another mechanism relevant to our studies with LCMV is the one documented for HTLV-1 spread between immune cells via formation of a transient interface, called virological synapse, where receptors and ligands are polarized, and this process is associated with polarization of the microtubule organizing center (MTOC) towards the intercellular interface (Bangham, 2003; Gross and Thoma-Kress, 2016; Jolly and Sattentau, 2004; Piguet and Sattentau, 2004). Detailed investigation of the intercellular interface between uninfected CAL-1 and LCMV-infected cells, as well as the intracellular distribution of virus and cellular components will help to characterize this novel LCMV cell entry pathway to infect pDCs.

Highlights.

Human pDC CAL-1 cells are refractory to infection with cell-free LCMV

LCMV is efficiently transmitted to CAL-1 cells from LCMV-infected non-pDC cells

Transmission of LCMV to CAL-1 cells requires cell-cell contact

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Kamihira for providing us with the CAL-1 cell line. We thank Mary E. Anderson and Kevin P. Campbell for providing us with recombinant adenovirus expressing DG and the mAb IIH6 to detect glycosylated αDG. We also thank B. Ware for his help with collecting and analyzing flow cytometry data. This research was supported by NIH/NIAID grants R21 AI121840 and R21 AI115348 to JCT and by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Daiichi Sankyo Foundation of Life Science, and KANAE Foundation for the Promotion of Medical Science to MI. This is manuscript # 29520 from The Scripps Research Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bangham CR. The immune control and cell-to-cell spread of human T-lymphotropic virus type 1. The Journal of general virology. 2003;84:3177–3189. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19334-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton LL, Mets MB. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: pediatric pathogen and fetal teratogen. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 1999;18:540–541. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199906000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton LL, Mets MB. Congenital lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection: decade of rediscovery. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2001;33:370–374. doi: 10.1086/321897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton LL, Mets MB, Beauchamp CL. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: emerging fetal teratogen. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2002;187:1715–1716. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.126297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battegay M. Quantification of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus with an immunological focus assay in 24 well plates. Altex. 1993;10:6–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bausch DG, Hadi CM, Khan SH, Lertora JJ. Review of the literature and proposed guidelines for the use of oral ribavirin as postexposure prophylaxis for Lassa fever. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2010;51:1435–1441. doi: 10.1086/657315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergthaler A, Flatz L, Hegazy AN, Johnson S, Horvath E, Lohning M, Pinschewer DD. Viral replicative capacity is the primary determinant of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus persistence and immunosuppression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:21641–21646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011998107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray M. Pathogenesis of viral hemorrhagic fever. Current opinion in immunology. 2005;17:399–403. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmeier MJ, Peters CJ, de la Torre JC. Arenaviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Knipe DM, Holey PM, editors. Field’s virology. 5. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; Philadelphia, PA: 2007. pp. 1791–1851. [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Henry MD, Borrow P, Yamada H, Elder JH, Ravkov EV, Nichol ST, Compans RW, Campbell KP, Oldstone MB. Identification of alpha-dystroglycan as a receptor for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus and Lassa fever virus. Science. 1998;282:2079–2081. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damonte EB, Coto CE. Treatment of arenavirus infections: from basic studies to the challenge of antiviral therapy. Advances in virus research. 2002;58:125–155. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(02)58004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreux M, Garaigorta U, Boyd B, Decembre E, Chung J, Whitten-Bauer C, Wieland S, Chisari FV. Short-range exosomal transfer of viral RNA from infected cells to plasmacytoid dendritic cells triggers innate immunity. Cell host & microbe. 2012;12:558–570. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emonet SF, Garidou L, McGavern DB, de la Torre JC. Generation of recombinant lymphocytic choriomeningitis viruses with trisegmented genomes stably expressing two additional genes of interest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:3473–3478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900088106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ervasti JM, Campbell KP. A role for the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex as a transmembrane linker between laminin and actin. The Journal of cell biology. 1993;122:809–823. doi: 10.1083/jcb.122.4.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan L, Briese T, Lipkin WI. Z proteins of New World arenaviruses bind RIG-I and interfere with type I interferon induction. Journal of virology. 2010;84:1785–1791. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01362-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer SA, Graham MB, Kuehnert MJ, Kotton CN, Srinivasan A, Marty FM, Comer JA, Guarner J, Paddock CD, DeMeo DL, Shieh WJ, Erickson BR, Bandy U, DeMaria A, Jr, Davis JP, Delmonico FL, Pavlin B, Likos A, Vincent MJ, Sealy TK, Goldsmith CS, Jernigan DB, Rollin PE, Packard MM, Patel M, Rowland C, Helfand RF, Nichol ST, Fishman JA, Ksiazek T, Zaki SR Team L.i.T.R.I. Transmission of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus by organ transplantation. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;354:2235–2249. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flatz L, Bergthaler A, de la Torre JC, Pinschewer DD. Recovery of an arenavirus entirely from RNA polymerase I/II-driven cDNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:4663–4668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600652103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming A, Sampey G, Chung MC, Bailey C, van Hoek ML, Kashanchi F, Hakami RM. The carrying pigeons of the cell: exosomes and their role in infectious diseases caused by human pathogens. Pathogens and disease. 2014;71:109–120. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisbert TW, Jahrling PB. Exotic emerging viral diseases: progress and challenges. Nature medicine. 2004;10:S110–121. doi: 10.1038/nm1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilliet M, Cao W, Liu YJ. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: sensing nucleic acids in viral infection and autoimmune diseases. Nature reviews Immunology. 2008;8:594–606. doi: 10.1038/nri2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross C, Thoma-Kress AK. Molecular Mechanisms of HTLV-1 Cell-to-Cell Transmission. Viruses. 2016;8:74. doi: 10.3390/v8030074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadi CM, Goba A, Khan SH, Bangura J, Sankoh M, Koroma S, Juana B, Bah A, Coulibaly M, Bausch DG. Ribavirin for Lassa fever postexposure prophylaxis. Emerging infectious diseases. 2010;16:2009–2011. doi: 10.3201/eid1612.100994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert T, Steinhagen F, Weisheit C, Baumgarten G, Hoeft A, Klaschik S. Synergistic Stimulation with Different TLR7 Ligands Modulates Gene Expression Patterns in the Human Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cell Line CAL-1. Mediators of inflammation. 2015;2015:948540. doi: 10.1155/2015/948540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imperiali M, Thoma C, Pavoni E, Brancaccio A, Callewaert N, Oxenius A. O Mannosylation of alpha-dystroglycan is essential for lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus receptor function. Journal of virology. 2005;79:14297–14308. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14297-14308.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inamori K, Yoshida-Moriguchi T, Hara Y, Anderson ME, Yu L, Campbell KP. Dystroglycan function requires xylosyl- and glucuronyltransferase activities of LARGE. Science. 2012;335:93–96. doi: 10.1126/science.1214115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki M, Ngo N, de la Torre JC. Sodium Hydrogen Exchangers Contribute to Arenavirus Cell Entry. Journal of virology. 2013 doi: 10.1128/JVI.02110-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahrling PB, Peters CJ. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. A neglected pathogen of man. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine. 1992;116:486–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly C, Sattentau QJ. Retroviral spread by induction of virological synapses. Traffic. 2004;5:643–650. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung A, Kato H, Kumagai Y, Kumar H, Kawai T, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Lymphocytoid choriomeningitis virus activates plasmacytoid dendritic cells and induces a cytotoxic T-cell response via MyD88. Journal of virology. 2008;82:196–206. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01640-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumagai Y, Kumar H, Koyama S, Kawai T, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Cutting Edge: TLR-Dependent viral recognition along with type I IFN positive feedback signaling masks the requirement of viral replication for IFN-{alpha} production in plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Journal of immunology. 2009;182:3960–3964. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz S, Rojek JM, Kanagawa M, Spiropoulou CF, Barresi R, Campbell KP, Oldstone MB. Posttranslational modification of alpha-dystroglycan, the cellular receptor for arenaviruses, by the glycosyltransferase LARGE is critical for virus binding. Journal of virology. 2005;79:14282–14296. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.22.14282-14296.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunz S, Sevilla N, McGavern DB, Campbell KP, Oldstone MB. Molecular analysis of the interaction of LCMV with its cellular receptor [alpha]-dystroglycan. The Journal of cell biology. 2001;155:301–310. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macal M, Lewis GM, Kunz S, Flavell R, Harker JA, Zuniga EI. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are productively infected and activated through TLR-7 early after arenavirus infection. Cell host & microbe. 2012;11:617–630. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T, Murata K, Fukushima T, Sugahara K, Tsuruda K, Anami M, Onimaru Y, Tsukasaki K, Tomonaga M, Moriuchi R, Hasegawa H, Yamada Y, Kamihira S. A novel plasmacytoid dendritic cell line, CAL-1, established from a patient with blastic natural killer cell lymphoma. International journal of hematology. 2005;81:148–154. doi: 10.1532/ijh97.04116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Sobrido L, Zuniga EI, Rosario D, Garcia-Sastre A, de la Torre JC. Inhibition of the type I interferon response by the nucleoprotein of the prototypic arenavirus lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. Journal of virology. 2006;80:9192–9199. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00555-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick JB, Fisher-Hoch SP. Lassa fever. Current topics in microbiology and immunology. 2002;262:75–109. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-56029-3_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mets MB, Barton LL, Khan AS, Ksiazek TG. Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus: an underdiagnosed cause of congenital chorioretinitis. American journal of ophthalmology. 2000;130:209–215. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00570-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michele DE, Barresi R, Kanagawa M, Saito F, Cohn RD, Satz JS, Dollar J, Nishino I, Kelley RI, Somer H, Straub V, Mathews KD, Moore SA, Campbell KP. Post-translational disruption of dystroglycan-ligand interactions in congenital muscular dystrophies. Nature. 2002;418:417–422. doi: 10.1038/nature00837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittelbrunn M, Sanchez-Madrid F. Intercellular communication: diverse structures for exchange of genetic information. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2012;13:328–335. doi: 10.1038/nrm3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olschlager S, Flatz L. Vaccination strategies against highly pathogenic arenaviruses: the next steps toward clinical trials. PLoS pathogens. 2013;9:e1003212. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppliger J, Torriani G, Herrador A, Kunz S. Lassa Virus Cell Entry via Dystroglycan Involves an Unusual Pathway of Macropinocytosis. Journal of virology. 2016;90:6412–6429. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00257-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piguet V, Sattentau Q. Dangerous liaisons at the virological synapse. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2004;114:605–610. doi: 10.1172/JCI22812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleet ML, Mathiesen A, DeMarino C, Akpamagbo YA, Barclay RA, Schwab A, Iordanskiy S, Sampey GC, Lepene B, Nekhai S, Aman MJ, Kashanchi F. Ebola VP40 in Exosomes Can Cause Immune Cell Dysfunction. Frontiers in microbiology. 2016;7:1765. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radoshitzky SR, Abraham J, Spiropoulou CF, Kuhn JH, Nguyen D, Li W, Nagel J, Schmidt PJ, Nunberg JH, Andrews NC, Farzan M, Choe H. Transferrin receptor 1 is a cellular receptor for New World haemorrhagic fever arenaviruses. Nature. 2007;446:92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature05539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. The Journal of cell biology. 2013;200:373–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201211138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigo WW, Ortiz-Riano E, Pythoud C, Kunz S, de la Torre JC, Martinez-Sobrido L. Arenavirus nucleoproteins prevent activation of nuclear factor kappa B. Journal of virology. 2012;86:8185–8197. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07240-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojek JM, Sanchez AB, Nguyen NT, de la Torre JC, Kunz S. Different mechanisms of cell entry by human-pathogenic Old World and New World arenaviruses. Journal of virology. 2008;82:7677–7687. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00560-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez AB, de la Torre JC. Rescue of the prototypic Arenavirus LCMV entirely from plasmid. Virology. 2006;350:370–380. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattentau Q. Avoiding the void: cell-to-cell spread of human viruses. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2008;6:815–826. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevilla N, Kunz S, Holz A, Lewicki H, Homann D, Yamada H, Campbell KP, de La Torre JC, Oldstone MB. Immunosuppression and resultant viral persistence by specific viral targeting of dendritic cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2000;192:1249–1260. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh BK, Li N, Mark AC, Mateo M, Cattaneo R, Sinn PL. Cell-to-Cell Contact and Nectin-4 Govern Spread of Measles Virus from Primary Human Myeloid Cells to Primary Human Airway Epithelial Cells. Journal of virology. 2016;90:6808–6817. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00266-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiropoulou CF, Kunz S, Rollin PE, Campbell KP, Oldstone MB. New World arenavirus clade C, but not clade A and B viruses, utilizes alpha-dystroglycan as its major receptor. Journal of virology. 2002;76:5140–5146. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.10.5140-5146.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhagen F, McFarland AP, Rodriguez LG, Tewary P, Jarret A, Savan R, Klinman DM. IRF-5 and NF-kappaB p50 co-regulate IFN-beta and IL-6 expression in TLR9-stimulated human plasmacytoid dendritic cells. European journal of immunology. 2013;43:1896–1906. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan BM, Emonet SF, Welch MJ, Lee AM, Campbell KP, de la Torre JC, Oldstone MB. Point mutation in the glycoprotein of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus is necessary for receptor binding, dendritic cell infection, and long-term persistence. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:2969–2974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019304108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiecki M, Colonna M. The multifaceted biology of plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Nature reviews Immunology. 2015;15:471–485. doi: 10.1038/nri3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teijaro JR, Ng C, Lee AM, Sullivan BM, Sheehan KC, Welch M, Schreiber RD, de la Torre JC, Oldstone MB. Persistent LCMV infection is controlled by blockade of type I interferon signaling. Science. 2013;340:207–211. doi: 10.1126/science.1235214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thery C, Ostrowski M, Segura E. Membrane vesicles as conveyors of immune responses. Nature reviews Immunology. 2009;9:581–593. doi: 10.1038/nri2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Swiecki M, McCartney SA, Colonna M. dsRNA sensors and plasmacytoid dendritic cells in host defense and autoimmunity. Immunological reviews. 2011;243:74–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieland SF, Takahashi K, Boyd B, Whitten-Bauer C, Ngo N, de la Torre JC, Chisari FV. Human plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus-infected cells in vitro. Journal of virology. 2014;88:752–757. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01714-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing J, Ly H, Liang Y. The Z proteins of pathogenic but not nonpathogenic arenaviruses inhibit RIG-I-like receptor-dependent interferon production. Journal of virology. 2015;89:2944–2955. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03349-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong P, Agosto LM, Munro JB, Mothes W. Cell-to-cell transmission of viruses. Current opinion in virology. 2013;3:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga EI, Liou LY, Mack L, Mendoza M, Oldstone MB. Persistent virus infection inhibits type I interferon production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells to facilitate opportunistic infections. Cell host & microbe. 2008;4:374–386. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]