Abstract

Background

Recent research among cancer survivors suggests that health behaviors and coping are intertwined, with important implications for positive behavior change and health. Informal caregivers may have poor health behaviors, and caregivers’ health behaviors have been linked to those of survivors.

Aims

This hypothesis generating study assessed the correlations among health behaviors and coping strategies in a population of lung and colorectal cancer caregivers.

Methods

This cross-sectional study used data from the Cancer Care Outcomes Research & Surveillance Consortium (CanCORS, 2003–2005). Caregivers (n=1,482) reported their health behaviors, coping, and sociodemographic and caregiving characteristics. Descriptive statistics assessed the distribution of caregivers’ health and coping behaviors, and multivariable linear regressions assessed the associations between health behaviors and coping styles.

Results

Many informal caregivers reported regular exercise (47%) and adequate sleep (37%); few reported smoking (19%) or binge drinking (7%). Problem-focused coping was associated with greater physical activity and less adequate sleep (Effect sizes [ES] up to 0.21, p<0.05). Those with some physical activity scored higher on emotion-focused coping, while binge drinkers scored lower (ES=0.16 and 0.27, p<0.05). Caregivers who reported moderate daily activity, current smoking, binge drinking, and feeling less well-rested scored higher on dysfunctional coping (ES up to 0.49, p<0.05).

Discussion

Health behaviors and coping strategies were interrelated among informal cancer caregivers. The relationships suggest avenues for future research, including whether targeting both factors concurrently may be particularly efficacious at improving informal caregiver self-care.

Conclusion

Understanding the link between health behaviors and coping strategies may inform health behavior research and practice.

Keywords: Caregivers, Coping Behavior, Health Behavior, Cancer, Family Relations

INTRODUCTION

Family and informal caregivers play a substantial role in the care of those who are ill or disabled in the United States (Levine, Halper, Peist, & Gould, 2010; Ockerby, Livingston, O’Connell, & Gaskin, 2013; Olson, 2012), and may be at increased risk of poor health outcomes (Pinquart & Sorensen, 2003, 2007; Schulz & Sherwood, 2008). Among caregivers of cancer survivors, specifically, there is evidence for greater levels of distress, depression, and anxiety compared to non-caregivers (Stenberg, Ruland, & Miaskowski, 2010). Physical health may also be adversely affected by caregiving: one recent study showed that spousal caregivers of cancer patients were at increased risk of coronary heart disease and stroke over time compared to spouses of unaffected individuals (Ji, Zoller, Sundquist, & Sundquist, 2012), while another provided evidence of autonomic imbalance in caregivers compared to controls (Lucini et al., 2008).

Poor health behaviors may play an important mediating role in health outcomes experienced by informal caregivers (Fredman et al., 2008; Ross, Sundaramurthi, & Bevans, 2013). Informal caregivers often put aside their own needs in order to care for their loved one(s), prioritizing patient needs and reporting concerns about lack of time and energy to engage in self-care (Applebaum, Farran, Marziliano, Pasternak, & Breitbart, 2014; Seal, Murray, & Seddon, 2015). Among cancer caregivers, the literature examining health behaviors is sparse (Gaugler, Eppinger, King, Sandberg, & Regine, 2013; Ross et al., 2013) and reflects conflicting results: while some studies report that cancer caregiving is associated with worse health behaviors (including inadequate physical activity, inadequate consumption of fruits and vegetables, smoking, and drug and alcohol abuse), other studies have reported more encouraging outcomes (Reeves, Bacon, & Fredman, 2012; Ross et al., 2013). For example, many caregivers do not get adequate physical activity (Mazanec, Daly, Douglas, & Lipson, 2011), however it is not clear that they get any less physical activity than comparable non-caregivers (Son et al., 2011), and in one study, a quarter of caregivers reported that their physical activity increased when they began caregiving (Humpel, Magee, & Jones, 2007), while another study reported that nearly half of caregivers perceived their physical activity levels to have decreased as a result of caregiving (Beesley, Price, Webb, Australian Ovarian Cancer Study, & Australian Ovarian Cancer Study-Quality of Life Study, 2011). The stress and burden of caregiving, too, may play a role in the health-promoting and health-risk behaviors in which caregivers engage (Fredman, Bertrand, Martire, Hochberg, & Harris, 2006; Hirano et al., 2011; Peng & Chang, 2013; Stults-Kolehmainen & Sinha, 2014). Stress in the general population has been associated with poor health behaviors including greater alcohol consumption, cigarette smoking, and decreased physical activity (Krueger & Chang, 2008), and in cancer caregivers, those with greater emotional strain reported fewer healthy behaviors (Bowman, Rose, & Deimling, 2005).

Given the conflicting evidence surrounding health behavior trends in informal caregivers, a better understanding of the factors influencing health behaviors in caregivers is needed. In particular, the potential link between stress and health behaviors suggests that a coping perspective may be informative. Park & Iacocca (Park & Iacocca, 2014) recently reviewed the broader literature examining the overlap between coping and health behaviors, and articulated important theoretical considerations. In particular, they highlighted the complexity of the intersections between health behaviors and coping: In many cases, individuals may use health behaviors as coping strategies, either intentionally (e.g., exercising to manage stress) or without their awareness (e.g., emotional eating). At the same time, health behaviors do not always serve a coping function: they may sometimes occur ancillary or consequent to another coping behavior (e.g., socializing at a bar to reduce stress, which may lead to greater alcohol consumption) or may reflect an underlying third variable that impacts both coping and health behaviors. Better understanding these interrelationships has important implications for facilitating and supporting positive behavior change and long-term health outcomes.

To our knowledge, the potential interrelationships between health behaviors and coping have not been explored in cancer caregivers. Not only are cancer caregivers at risk of poor health outcomes that may be related to negative health behaviors (Ross et al., 2013), but positive health behaviors in caregivers may enhance health behaviors in cancer survivors (Daly et al., 2002; James et al., 2011; Martire, Lustig, Schulz, Miller, & Helgeson, 2004), particularly as these behaviors may be similar between caregivers and their care recipients (Weaver, Rowland, Augustson, & Atienza, 2011). This hypothesis-generating study therefore sought to determine the correlation between health behaviors and coping strategies among a population of informal caregivers of lung and colorectal cancer patients.

METHODS

This study used data from the “Share Thoughts on Care Caregiver Study” conducted by the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) Consortium as an ancillary to the patient cohort study of lung and colorectal cancer survivors. Detailed information about the CanCORS study protocols has been previously published (Ayanian et al., 2004; Malin et al., 2006; van Ryn et al., 2011). Briefly, the CanCORS consortium consisted of seven study sites ascertaining patients from either cancer registries (5 sites) or a healthcare system (2 sites) in the US between 2003 and 2005. Caregivers were nominated by the cancer survivors in the core CanCORS survey and invited to participate via mail (including a self-administered questionnaire, information about the study, a postage-paid return envelope, and a $20 incentive). Two cross-sectional samples of caregivers were identified shortly after the baseline interview with the survivor (n=825) or shortly after the survivors’ first follow-up interview (n=802). Caregivers completed the self-administered questionnaire on average 7.3 or 15.6 months since the survivors’ diagnosis, respectively.

Measures

Health Behaviors

Participants were asked how many days they do moderate-intensity physical activity in a typical week, and how long they typically do these activities. We calculated the number of minutes per week of physical activity, and categorized participants as having no physical activity (0 minutes), some activity (1–149 minutes) or activity meeting the national recommendations (150+ minutes)(US Department of Health & Human Services, 2008). Daily activity (measured separately from physical activity, including “work, housework, going to and attending classes, and what you normally do throughout a typical day”) was self-reported by participants and categorized as 1) sit during the day and do not walk about very much (“low”), 2) stand/walk about quite a lot, but do not carry or lift things often (“moderate”), or 3) carry/lift light or heavy loads or climb stairs or hills (“high”). Smoking status was categorized as never, former, or current smoker based on whether the participant had smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and whether they reported smoking at the time of the survey. Participants were categorized according to alcohol consumption patterns as: non-drinker (no alcohol consumption in the past 30 days), drinker, or binge drinker (5+ drinks in a row on one or more days in the past 30 days). Sleep was assessed based on self-report of the extent to which the caregiver reported getting enough sleep in the past 30 days to feel rested 1) all or most of the time, 2) a good bit/some of the time, or 3) a little or none of the time. Health behavior items were primarily based on questions from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2001) and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (National Center for Health Statistics & Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2002).

Coping

Subjects responded to a subset of questions from the Brief COPE (Carver, 1997). The 13 items used in this study assessed 13 subscales: self-distraction, denial, substance use, emotional support, behavioral disengagement, active coping, venting, instrumental support, planning, positive reframing, acceptance, self-blame and religion. Respondents indicated how much they used each strategy in the past two weeks on a four-point Likert scale (not at all [1] to a lot [4]). Summary scales were also created for problem-focused (sum of: active coping, planning, and instrumental support items), emotion-focused (sum of: acceptance, emotional support, positive reframing, and religion items), and dysfunctional coping (sum of: behavioral disengagement, denial, self-distraction, self-blame, substance use, and venting items), based on previous studies (Coolidge, Segal, Hook, & Stewart, 2000; C. Cooper, Katona, & Livingston, 2008). For those missing responses to half of the items or fewer (1 item for problem-focused coping; 2 items for emotion-focused coping, or 3 items for dysfunctional coping), the mean of the other items was imputed for the missing item; the scale was unscored for those missing more items.

Sociodemographic/Health Characteristics

Caregivers reported their age, gender, race/ethnicity (collapsed to white-non-Hispanic or other), household income (categorized into quartiles), education status (collapsed to high school or less versus some college/trade school or more), employment status (does not work for pay, works for pay <35 hours/week, works for pay 35+ hours/week) and marital status (collapsed to married/partnered versus divorced/widowed/separated/never married) in the questionnaire. Caregivers also self-reported whether they had seen a doctor or other healthcare professional in the past year.

Cancer Characteristics

Survivor’s age, gender, type of cancer (lung or colorectal) and stage at diagnosis were obtained from the CanCORS core data. Type(s) of treatment received (surgery, radiation, and/or chemotherapy; not mutually exclusive) was self-reported by survivors.

Caregiving Characteristics

Information regarding the proportion of the patient’s care that the target caregiver provides (“all or almost all”; “most”; or “50–50” or “less than half”), relationship to the cancer survivor (collapsed to spouse/partner, child, parent/sibling, or other), co-residence with the survivor (yes/no), hours per week of care provided, and number of household tasks for which help was provided (including basic or instrumental activities of daily living [ADL/IADLs]) was collected in the caregiver questionnaire.

Missing data were treated as follows: variables with >2% missing/unreported were recoded to include a “missing/unknown” category. Those caregivers missing data on other variables (i.e., variables with ≤2% missing: education, marital status, cancer type, relationship with the care recipient, co-residential status with the care recipient, hours of sleep/feeling well-rested), key sociodemographic variables (i.e., caregiver age or gender), or coping summary scales were dropped from the analysis as missing/unknown categories for these variables in the final sample would have been too small to allow meaningful analysis. This resulted in a final sample of 1,482. Compared to those in the final sample, those dropped due to missing data (n=145) were more likely to be non-white, have a high school education or less, and have unreported income and employment status.

Statistical Analyses

Characteristics of the caregivers in the sample were examined using descriptive statistics (frequency distributions for categorical variables; histograms and univariate analyses (i.e., mean/standard deviation) for continuous variables). Proportions of caregivers reporting each health behavior and coping style were calculated. Multivariable linear regression was used to assess the independent association of each health behavior and 1) problem-focused, 2) emotion-focused, and 3) dysfunctional coping, controlling for the sociodemographic/health and caregiving characteristics listed above. Parsimonious models were selected by testing the associations between the potential control variables and the outcome variables, and only those covariates associated with the dependent variables were included in the final model; the results from these models did not differ from those that included all possible covariates. For the association between drinking and dysfunctional coping, substance use was excluded from the dysfunctional coping scale. Effect sizes (ES) were calculated using Cohen’s d (Cohen, 1988).

As a sensitivity analysis, we also ran regressions with the health behaviors included simultaneously. In this analysis, the dysfunctional coping scale excluded the item on substance use.

RESULTS

Table 1 displays the sociodemographic and caregiving characteristics of the informal caregivers. The majority of caregivers were older (73% >50 years of age), female (75%), white (non-Hispanic) (73%), and well-educated (66% had at least some college education). Forty-six percent were not employed outside the home, and 82% were married or partnered. They were caring for lung (N=691) and colorectal (N=791) cancer survivors at all disease stages (0–I: 34%; II–III: 48%; IV: 18%) almost a quarter of whom (24%) were aged 75 or older. Most were primary caregivers, providing all or almost all of the care needed by the survivor (52%), were providing care to a spouse or partner (64%), and lived with the survivor (74%). A sizeable proportion (20%) provided more than 35 hours of care per week.

Table 1.

Characteristics of lung and colorectal cancer survivors and their caregivers in the CanCORS (2003–2005)

| Total N=1,482 % or mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|

| Caregiver Sociodemographic Characteristics | |

| Age | |

| 20 to 50 years | 27.24 |

| 51 to 60 years | 28.52 |

| 61 to 70 years | 24.14 |

| 71 years or older | 20.09 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 24.81 |

| Female | 75.19 |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Other | 27.44 |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 72.56 |

| Annual Household Income | |

| <12,000 | 13.35 |

| 12,000–26,999 | 14.03 |

| 27,000–47,999 | 14.09 |

| 48,000+ | 15.44 |

| Unknown/Unreported | 43.09 |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 34.32 |

| Some college or more | 65.68 |

| Employment Status | |

| Does not work for money | 45.72 |

| Works for money, <35 hrs/wk | 15.37 |

| Works for money, 35+ hrs/wk | 34.59 |

| Unknown/Unreported | 4.32 |

| Marital Status | |

| Divorced/Widowed/Separated/Never Married | 18.00 |

| Married/Partnered | 82.00 |

| Cancer Characteristics | |

| Type of Cancer | |

| Lung | 46.66 |

| Colorectal | 53.34 |

| Stage at Diagnosis | |

| 0–I | 33.92 |

| II–III | 48.21 |

| IV | 17.87 |

| Treatment Received (not mutually exclusive) | |

| Surgery | 68.31 |

| Radiation Therapy | 26.23 |

| Chemotherapy | 58.80 |

| Caregiving Characteristics | |

| Amount of care provided | |

| Half or Less than half | 21.78 |

| Most | 21.31 |

| All or almost all | 52.26 |

| Unknown/unreported | 4.65 |

| Relationship to survivor | |

| Spouse/partner | 63.72 |

| Child | 14.70 |

| Parent/Sibling | 14.97 |

| Other | 6.61 |

| Live with survivor | |

| No | 26.43 |

| Yes | 73.57 |

| Hours per week | |

| 1 or fewer | 22.66 |

| 1 to 10 | 25.96 |

| 11 to 35 | 26.16 |

| More than 35 | 19.89 |

| Unknown/unreported | 5.33 |

| Number of ADL/IADLs | 4.37 (3.87) |

| Age of Care Recipient | |

| 0–54 | 17.60 |

| 55–64 | 29.13 |

| 65–74 | 29.67 |

| 75+ | 23.60 |

| Gender of Care recipient | |

| Male | 62.24 |

| Female | 37.76 |

SD: Standard deviation; ADL/IADLs: Basic and instrumental activities of daily living

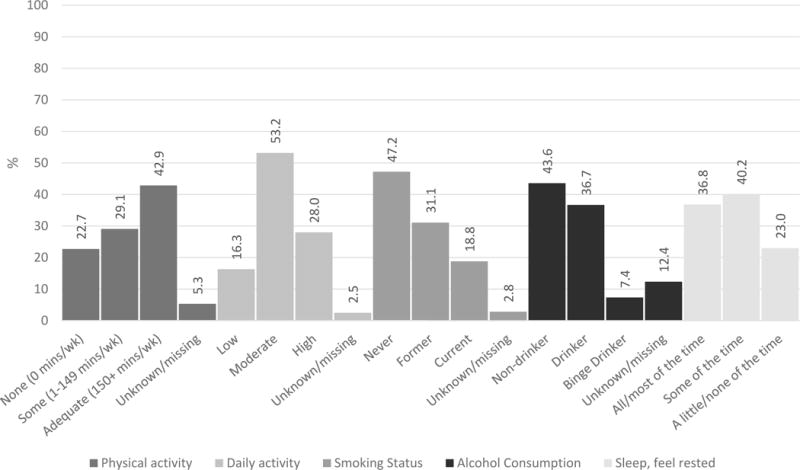

Figure 1 displays the distribution of health behaviors among the informal caregivers. Nearly half of caregivers (43%) reported at least 150 minutes per week of moderate physical activity, in line with national guidelines. However, more than one fifth of caregivers reported no moderate physical activity (23%). Most caregivers (81%) reported some level of non-exercise daily activity, with only 16% reporting low activity (“sit during the day and do not walk about very much”). Nineteen percent were current smokers, 37% reported drinking, and 7% reported binge drinking. On average, caregivers reported an adequate amount of sleep (~7 hours per night), but nearly a quarter (23%) of caregivers reported that they rarely got enough sleep to feel rested in the morning.

Figure 1. Distribution of health behaviors among informal cancer caregivers (n=1,482).

Data are from the “Share Thoughts on Care Caregiver Study” conducted by the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) Consortium (2003–2005).

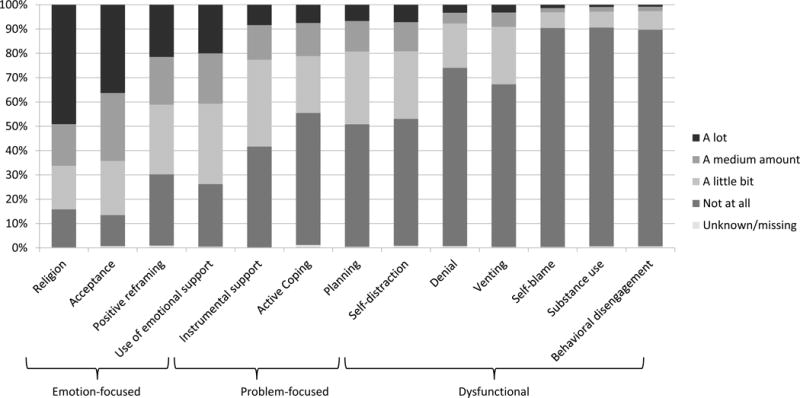

Figure 2 displays the distribution of coping strategies. Caregivers reported using a variety of coping styles, the most frequently endorsed among these being emotion-focused coping strategies (“a lot”: religion [49%], acceptance [36%], positive reframing [21%], and emotional support [20%]). Conversely, a small minority reported using dysfunctional coping strategies (“a lot”: behavioral disengagement [1%], substance use [1%], self-blame [1%], venting [3%], denial [3%]).

Figure 2. Coping strategies reported by informal cancer caregivers (n=1,482).

Data are from the “Share Thoughts on Care Caregiver Study” conducted by the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) Consortium (2003–2005). Items are from the Brief COPE questionnaire.

Table 2 presents the results of the multivariable linear regressions by coping subscale; results are categorized below by coping strategy.

Table 2.

Associations between Health Behaviors and Coping Strategies among Informal Caregivers of Lung and Colorectal Cancer Survivors (2003–2005, n=1,482)a

| Problem-Focused Coping | Emotion-Focused Coping | Dysfunctional Coping | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | SE | ES | p-value | Beta | SE | ES | p-value | Beta | SE | ES | p-value | |

| Health Behaviors | ||||||||||||

| Physical activity | — | |||||||||||

| None (0 mins/wk) | REF | REF | REF | |||||||||

| Some (1–149 mins/wk) | 0.35 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.49 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.03 | −0.12 | 0.16 | −0.05 | 0.46 |

| Adequate (150+ mins/wk) | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.41 | −0.11 | 0.15 | −0.05 | 0.47 |

| Unknown/missing | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.89 | 0.19 | 0.38 | 0.06 | 0.61 | −0.54 | 0.28 | −0.24 | 0.05 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Daily activity | ||||||||||||

| Low: Sit during the day and do not walk about very much | REF | REF | REF | |||||||||

| Moderate: Stand/walk about quite a lot, but do not carry or lift things often | −0.26 | 0.16 | −0.12 | 0.12 | 0.32 | 0.23 | 0.10 | 0.17 | −0.36 | 0.17 | −0.16 | 0.03 |

| High: Carry/lift light or heavy loads or climb stairs or hills | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.89 | 0.36 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.15 | −0.17 | 0.18 | −0.07 | 0.36 |

| Unknown/missing | −0.21 | 0.39 | −0.09 | 0.59 | 0.75 | 0.54 | 0.24 | 0.17 | −0.21 | 0.40 | −0.09 | 0.60 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Smoking status | ||||||||||||

| Never | REF | REF | REF | |||||||||

| Former | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.05 | 0.38 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 0.02 | 0.69 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.43 |

| Current | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.22 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 0.49 | 0.16 | 0.21 | 0.00 |

| Unknown/missing | −0.14 | 0.35 | −0.06 | 0.69 | 0.13 | 0.49 | 0.04 | 0.79 | 0.40 | 0.36 | 0.17 | 0.27 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Alcohol Consumptionb | ||||||||||||

| Non-drinker | REF | REF | REF | |||||||||

| Drinker | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.07 | 0.25 | −0.35 | 0.18 | −0.11 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.77 |

| Binge Drinker (5+ drinks in a row on one or more days in the past month) | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.56 | −0.84 | 0.33 | −0.27 | 0.01 | 0.45 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.04 |

| Unknown/missing | −0.04 | 0.18 | −0.02 | 0.83 | 0.21 | 0.26 | 0.07 | 0.41 | 0.06 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.71 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Sleep - Feel rested: | ||||||||||||

| All/most of the time | REF | REF | REF | |||||||||

| A good bit/some of the time | 0.33 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.01 | 0.85 | 0.71 | 0.13 | 0.31 | <.0001 |

| A little/none of the time | 0.46 | 0.15 | 0.21 | 0.00 | −0.06 | 0.22 | −0.02 | 0.77 | 1.11 | 0.16 | 0.49 | <.0001 |

Each health behavior was run in an independent regression, controlling for: caregiver age, gender, race/ethnicity, income (quartiles), education, employment status, marital status, hours per week of care, participation timepoint and care recipient age and gender

Dysfucntional coping scale excluded “substance abuse” item

SE: Standard error; ES: Effect size (Cohen’s d); REF: Reference category

Problem-focused coping

Caregivers who reported at least some physical activity or who were less well-rested had greater use of problem-focused coping strategies (p<0.05). Specifically, caregivers who reported at least some physical activity had problem-focused coping scores more than 0.3 points higher than those reporting no physical activity (some activity: ES=0.16, p=0.02; activity meeting national guidelines: ES=0.14, p=0.04). Caregivers who reported feeling well rested some of the time had problem-focused coping scores that were 0.33 points higher (ES=0.15, p=0.01), and those who reported rarely feeling well rested had scores 0.46 points higher (ES=0.21, p<0.01), compared to those who felt well-rested all or most of the time.

Emotion-focused coping

Caregivers with some physical activity also reported greater use of emotion-focused coping, while binge drinkers reported less use of emotion-focused coping. Specifically, caregivers reporting some physical activity had emotion-focused coping scores 0.49 points higher than those reporting no physical activity (ES=0.16, p=0.03). Binge drinkers had scores 0.84 points lower (ES=0.27, p=0.01) than non-drinkers on the emotion-focused coping scale.

Dysfunctional coping

Finally, those with a moderate amount of daily activity (standing/walking about during the day) had less use of dysfunctional coping, while current smokers, binge drinkers, and those who felt less well-rested reported higher levels of dysfunctional coping. Specifically, those who stood or walked during the day, outside of physical activity (moderate daily activity), had dysfunctional coping scores 0.36 points lower than those reporting that they sat all or most of the day (ES=0.16, p=0.03). Current smokers had dysfunctional coping scores that were 0.49 points higher (ES=0.21, p<0.01) than non-smokers, and binge drinkers had scores 0.45 points higher (ES=0.20, p=0.04) than non-drinkers. Those who felt well-rested some of the time has dysfunctional coping scores that were 0.71 points higher (ES=0.31, p<0.0001) and those who rarely felt well-rested had scores 1.11 points higher (ES=0.49, p< 0.0001) than caregivers who felt well-rested all or some of the time.

As a sensitivity analysis, we also ran regressions with the health behaviors included simultaneously (Appendix 1). The results did not change substantively for problem- or emotion-focused coping. For dysfunctional coping, moderate daily activity was no longer statistically significant (Beta=−0.22, ES=0.10, p=0.16), and current smoking status became borderline (Beta=0.30, ES=0.13, p=0.05).

DISCUSSION

This study examined the distribution of and interrelationships among health behaviors and coping strategies in a large sample (N=1,482) of informal caregivers of lung and colorectal cancer survivors, filling a gap in our understanding of how informal caregivers care for themselves. The findings show that most caregivers get at least some regular physical activity (72%) as well as general daily activity (81%), and report feeling well-rested at least some of the time (77%), with few caregivers reporting current smoking (19%) or binge drinking (7%). These findings are consistent with several previous studies (Reeves et al., 2012; Rha, Park, Song, Lee, & Lee, 2015; Ross et al., 2013) although the literature overall has been conflicting. Caregivers also used a variety of coping strategies, with emotion-focused strategies (i.e., religion, acceptance, positive reframing) endorsed most frequently, and dysfunctional strategies (i.e., behavioral disengagement, substance use, and self-blame) reported least frequently. Previous research suggests that this may be adaptive; among dementia caregivers, therapies promoting emotion-focused coping are efficacious in reducing anxiety while those teaching problem-focused coping alone are not (C Cooper, Balamurali, & Livingston, 2007).

This study extends the literature by revealing the interrelationships among health behaviors and coping strategies. This link has been conceptualized in theory (Park & Iacocca, 2014) but only sparsely examined in the general population and, to our knowledge, has not be examined previously in an informal or family caregiving population. We discuss several of the interrelationships observed in this study to highlight avenues for future research to better elucidate these relationships.

In the present study, caregivers who reported feeling less well-rested had higher problem-focused coping scores. The problem-focused subscale consisted of active coping (trying to do something about the situation), obtaining instrumental support (help from others), and planning or strategizing. There are several plausible ways to conceptualize this correlation. It is possible that these problem-focused approaches interfere with sleep either directly – by taking up time that would otherwise be spent sleeping – or indirectly, such as by making it hard for caregivers to fall asleep or stay asleep (e.g., due to rumination). Alternatively, caregivers with insomnia could increase their use of problem-focused coping strategies due to extra time awake. It is also possible that lack of sleep may itself contribute to increased problems in managing care and hence the need for greater demand for problem-solving efforts.

Binge drinking and smoking were associated with higher scores on the dysfunctional coping scale. These behaviors might plausibly occur as part of a dysfunctional coping strategy (e.g., drinking or smoking as a self-distraction or self-soothing tool), or as an ancillary to other coping behaviors (e.g., going out with friends as a self-distraction approach, and drinking or smoking as part of the social experience). The correlation between these health behaviors and coping strategies could also be related to a third characteristic – such as personality or propensity to engage in addictive behaviors – that may contribute to the inclination to both drink or smoke and use other dysfunctional coping approaches. Moderate daily activity was associated with lower dysfunctional coping scores, and might be related to or a proxy for caregiving intensity.

These findings suggest several future research directions. Understanding the directionality of these interrelationships and the pathways by which they occur will be critical. As illustrated above and discussed by Park & Iacocca (Park & Iacocca, 2014), caregivers’ health behaviors may be a form of coping, be impacted by coping strategies (as has been empirically shown among cancer survivors (Parelkar, Thompson, Kaw, Miner, & Stein, 2013; Park, Edmondson, Fenster, & Blank, 2008)), contribute to increased or decreased use of other coping strategies, or be ancillary to other coping behaviors. Health behaviors and coping may also be linked via a third variable. Importantly, these relationships may vary for different individuals or at different time points; future theory-driven, longitudinal research will be needed to better understand these relationships.

Future research may also wish to consider how these interrelationships may translate into potential targets to improve caregiver health behaviors and coping strategies. US adults often list health behaviors as some of their top approaches to coping with stress (American Psychological Association, 2012). In some cases, even poor health behaviors may effectively reduce stress or improve well-being in the short-run (Jackson, Knight, & Rafferty, 2010), despite the potential to be deleterious in the long run. Those who perceive that they are using a health behavior as a coping strategy use that behavior more under stress (Park & Iacocca, 2014). While this can have adverse outcomes (e.g., heavy alcohol use), it is also possible that this can be leveraged to enhance or encourage positive health behaviors, for example by reminding caregivers that physical activity can help them modulate their stress and burden. Conversely, targeting health behaviors directly may be ineffective if the behavior is being driven by a heavily-used coping strategy. It is possible that modifying coping strategies may provide a point of intervention to indirectly improve health behaviors and improve caregiver health outcomes. Decreasing dysfunctional coping, for example, may help to improve negative health behaviors such as binge drinking or smoking. Future research might examine whether intervening on coping strategies and health behaviors simultaneously might more effectively improve health behaviors and caregiver outcomes. Given that 23% of caregivers report no physical activity and the same proportion struggle with adequate sleep suggests these particular behaviors may be ripe targets for intervention.

This study should be interpreted in light of several potential limitations. This study was conducted using a cross-sectional design, and as such directionality of the associations could not be assessed. To our knowledge, this is true of all existing health-behavior studies in a cancer caregiving population (Mazanec, Flocke, & Daly, 2015; Reeves et al., 2012; Ross et al., 2013) and longitudinal studies are urgently needed. The 145 caregivers who were dropped due to missing data were more likely to be non-white and have lower education than those in the final sample, and may represent a vulnerable subgroup that is not represented here. We were also unable to examine in this dataset whether health behaviors were intentionally used as coping behaviors or were related to coping via other pathways. Nor were we able to evaluate deviations from the baseline level of each health behavior prior to caregiving (Park & Iacocca, 2014). The data in this study were collected by self-report, potentially resulting in over-reporting of positive health behaviors (e.g., physical activity) and under-reporting of negative health behaviors (e.g., alcohol use for which there was the largest percent with missing data). These limitations may also contribute to the relatively small effect sizes observed for the associations between health behaviors and coping. However, the individual effect sizes observed in this study were in line with or in some cases smaller than those reported in intervention studies (Li et al., 2014; Powell, Fraser, Brockway, Temkin, & Bell, 2016), highlighting the potential clinical significance of the associations between health behaviors and coping strategies, especially when health behaviors are considered jointly. Further, this study was conducted in a large, multi-site dataset and is one of the first to explore the interrelationships between health behaviors and coping in a cancer caregiving population.

In conclusion, this study evaluated the distribution of and interrelationships among health behaviors and coping among family caregivers of lung and colorectal cancer survivors. Health behaviors and coping strategies were correlated. Future research is needed to better understand the mechanisms linking health behaviors and coping and translate this knowledge into interventions that can improve health outcomes for caregivers and their families.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The CanCORS data were collected with funding from the National Cancer Institute (U01 CA93324, U01 CA93326, U01 CA93329, U01 CA93332, U01 CA93339, U01 CA93344, and U01 CA93348) and the Department of Veterans Affairs (CRS 02-164). The manuscript was prepared as part of the authors’ official duties as United States Federal Government employees. The views expressed represent those of the authors and not those of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

References

- American Psychological Association. Stress by generation. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2012/generation.pdf.

- Applebaum AJ, Farran CJ, Marziliano AM, Pasternak AR, Breitbart W. Preliminary study of themes of meaning and psychosocial service use among informal cancer caregivers. Palliat Support Care. 2014;12(2):139–148. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Fletcher RH, Fouad MN, Harrington DP, Kahn KL, West DW. Understanding cancer treatment and outcomes: the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(15):2992–2996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beesley VL, Price MA, Webb PM, Australian Ovarian Cancer Study, G. Australian Ovarian Cancer Study-Quality of Life Study, I Loss of lifestyle: health behaviour and weight changes after becoming a caregiver of a family member diagnosed with ovarian cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19(12):1949–1956. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman KF, Rose JH, Deimling GT. Families of long-term cancer survivors: health maintenance advocacy and practice. Psychooncology. 2005;14(12):1008–1017. doi: 10.1002/pon.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int J Behav Med. 1997;4(1):92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey questionnaire. Atlanta, Georgia: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Coolidge FL, Segal DL, Hook JN, Stewart S. Personality disorders and coping among anxious older adults. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2000;14(2):157–172. doi: 10.1016/S0887-6185(99)00046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Balamurali T, Livingston G. A systematic review of the prevalence and associates of anxiety in carers of people with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics. 2007;28:1–21. doi: 10.1017/S1041610206004297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C, Katona C, Livingston G. Validity and reliability of the brief COPE in carers of people with dementia: the LASER-AD Study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196(11):838–843. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31818b504c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly J, Sindone AP, Thompson DR, Hancock K, Chang E, Davidson P. Barriers to participation in and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs: a critical literature review. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2002;17(1):8–17. doi: 10.1111/j.0889-7204.2002.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman L, Bertrand RM, Martire LM, Hochberg M, Harris EL. Leisure-time exercise and overall physical activity in older women caregivers and non-caregivers from the caregiver-SOF study. Preventive medicine. 2006;43(3):226–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredman L, Cauley JA, Satterfield S, Simonsick E, Spencer SM, Ayonayon HN, Health, A. B. C. S. G. Caregiving, mortality, and mobility decline: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) Study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(19):2154–2162. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler JE, Eppinger A, King J, Sandberg T, Regine WF. Coping and its effects on cancer caregiving. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(2):385–395. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1525-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano A, Suzuki Y, Kuzuya M, Onishi J, Hasegawa J, Ban N, Umegaki H. Association between the caregiver’s burden and physical activity in community-dwelling caregivers of dementia patients. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2011;52(3):295–298. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humpel N, Magee C, Jones SC. The impact of a cancer diagnosis on the health behaviors of cancer survivors and their family and friends. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2007;15(6):621–630. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Knight KM, Rafferty JA. Race and unhealthy behaviors: chronic stress, the HPA axis, and physical and mental health disparities over the life course. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(5):933–939. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James EL, Stacey F, Chapman K, Lubans DR, Asprey G, Sundquist K, Girgis A. Exercise and nutrition routine improving cancer health (ENRICH): the protocol for a randomized efficacy trial of a nutrition and physical activity program for adult cancer survivors and carers. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:236. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J, Zoller B, Sundquist K, Sundquist J. Increased risks of coronary heart disease and stroke among spousal caregivers of cancer patients. Circulation. 2012;125(14):1742–1747. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.057018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger PM, Chang VW. Being poor and coping with stress: health behaviors and the risk of death. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(5):889–896. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine C, Halper D, Peist A, Gould DA. Bridging troubled waters: family caregivers, transitions, and long-term care. Health Aff. 2010;29(1):116–124. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R, Cooper C, Barber J, Rapaport P, Griffin M, Livingston G. Coping strategies as mediators of the effect of the START (strategies for RelaTives) intervention on psychological morbidity for family carers of people with dementia in a randomised controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2014;168:298–305. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucini D, Cannone V, Malacarne M, Bruno D, Beltrami S, Pizzinelli P, Pagani M. Evidence of autonomic dysregulation in otherwise healthy cancer caregivers: a possible link with health hazard. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(16):2437–2443. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malin JL, Ko C, Ayanian JZ, Harrington D, Nerenz DR, Kahn KL, Ganz PA. Understanding cancer patients’ experience and outcomes: development and pilot study of the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance patient survey. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14(8):837–848. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0902-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martire LM, Lustig AP, Schulz R, Miller GE, Helgeson VS. Is it beneficial to involve a family member? a meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for chronic illness. Health psychology. 2004;23(6):599. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazanec SR, Daly BJ, Douglas SL, Lipson AR. Work productivity and health of informal caregivers of persons with advanced cancer. Res Nurs Health. 2011;34(6):483–495. doi: 10.1002/nur.20461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazanec SR, Flocke SA, Daly BJ. Health behaviors in family members of patients completing cancer treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2015;42(1):54–62. doi: 10.1188/15.ONF.54-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Health Statistics & Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) questionnaire and exam protocol 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Ockerby C, Livingston P, O’Connell B, Gaskin CJ. The role of informal caregivers during cancer patients’ recovery from chemotherapy. Scand J Caring Sci. 2013;27(1):147–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson RE. Is cancer care dependant on informal carers? Aust Health Rev. 2012;36(3):254–257. doi: 10.1071/AH11086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parelkar P, Thompson NJ, Kaw CK, Miner KR, Stein KD. Stress Coping and Changes in Health Behavior Among Cancer Survivors: A Report from the American Cancer Society’s Study of Cancer Survivors-II (SCS-II) Journal of psychosocial oncology. 2013;31(2):136–152. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2012.761322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Edmondson D, Fenster JR, Blank TO. Positive and negative health behavior changes in cancer survivors: a stress and coping perspective. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(8):1198–1206. doi: 10.1177/1359105308095978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Iacocca MO. A stress and coping perspective on health behaviors: theoretical and methodological considerations. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2014;27(2):123–137. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2013.860969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng HL, Chang YP. Sleep disturbance in family caregivers of individuals with dementia: a review of the literature. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2013;49(2):135–146. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and aging. 2003;18(2):250–267. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sorensen S. Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(2):P126–137. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.p126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell JM, Fraser R, Brockway JA, Temkin N, Bell KR. A Telehealth Approach to Caregiver Self-Management Following Traumatic Brain Injury: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2016;31(3):180–190. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves KW, Bacon K, Fredman L. Caregiving associated with selected cancer risk behaviors and screening utilization among women: cross-sectional results of the 2009 BRFSS. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:685. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rha SY, Park Y, Song SK, Lee CE, Lee J. Caregiving burden and health-promoting behaviors among the family caregivers of cancer patients. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19(2):174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross A, Sundaramurthi T, Bevans M. A labor of love: the influence of cancer caregiving on health behaviors. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36(6):474–483. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182747b75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R, Sherwood PR. Physical and mental health effects of family caregiving. Am J Nurs. 2008;108(9 Suppl):23–27. doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000336406.45248.4c. quiz 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal K, Murray CD, Seddon L. The experience of being an informal “carer” for a person with cancer: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Palliat Support Care. 2015;13(3):493–504. doi: 10.1017/S1478951513001132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Son KY, Park SM, Lee CH, Choi GJ, Lee D, Jo S, Cho B. Behavioral risk factors and use of preventive screening services among spousal caregivers of cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2011;19(7):919–927. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0889-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stenberg U, Ruland CM, Miaskowski C. Review of the literature on the effects of caring for a patient with cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19(10):1013–1025. doi: 10.1002/pon.1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stults-Kolehmainen MA, Sinha R. The effects of stress on physical activity and exercise. Sports Med. 2014;44(1):81–121. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0090-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health & Human Services. Physical activity guidelines for Americans 2008 [Google Scholar]

- van Ryn M, Sanders S, Kahn K, van Houtven C, Griffin JM, Martin M, Rowland J. Objective burden, resources, and other stressors among informal cancer caregivers: a hidden quality issue? Psychooncology. 2011;20(1):44–52. doi: 10.1002/pon.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Augustson E, Atienza AA. Smoking concordance in lung and colorectal cancer patient-caregiver dyads and quality of life. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(2):239–248. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.