Abstract

Understanding the origins of mutations in genes and how these give rise to tumors is a central problem in biology. A new study in The EMBO Journal has produced a 3‐dimensional map of DNA damage induced by sunlight, a pervasive carcinogen, and found that genes on the periphery, located near the nuclear lamin, are more prone to damage than those in the interior of the nucleus. In addition, high levels of damage showed a remarkable correlation with driver mutations in melanoma.

Subject Categories: Cancer; Chromatin, Epigenetics, Genomics & Functional Genomics; DNA Replication, Repair & Recombination

New technologies often go hand in hand with great discovery and exploration. Leuwenhoek's primitive microscope allowed investigation of unicellular creatures in pond water and the beginnings of cell biology in the 1670s. The Hubble telescope has given unprecedented maps of the universe, verifying the existence of black holes at galactic centers. In his book describing the life of Gerard Mercator, one of the most important cartographers in our history, Nicholas Crane wrote, “Maps codify the miracle of existence” (Crane, 2003). Molecular biology has produced a treasure trove of big data in the form of DNA sequence and epigenetic information about how our genome works. These data take on a whole new meaning as they are mapped into the 3‐D architecture of the human nucleus. The human genome is remarkable in that over 2 m of DNA are packed into a highly organized nucleus of about 700 cubic microns or just 0.7 pl. Over the last few years, scientists using chromosome conformation capture techniques (3‐C and Hi‐C) have discovered that genes have unique locations or zip codes within the mammalian nucleus (Fraser et al, 2015; Dekker, 2016). Nuclear DNA is organized into discrete loops, topologically associated domains (TADs), and interacting blocks of chromatin called compartments. Lamin‐associated domains (LADs) are relatively gene‐poor genomic sequences associated with a group of proteins called lamins, located near the nuclear periphery. Simultaneously with mapping genome architecture has been the development of tools to map DNA damage and repair in bacteria, yeast, and mammalian cells (Adar et al, 2016; Mao et al, 2016; Yu et al, 2016; Adebali et al, 2017). As life crawled out of the ocean, terrestrial genomes were shaped by a constant bombardment of UV light from the sun, a potent mutagen and carcinogen. In the study by García‐Nieto et al (2017), the authors have developed a novel method to map UV‐induced photoproducts across the genome. Surprisingly, they found that the most UV‐induced damage occurs in highly condensed non‐coding DNA at the periphery of the nucleus; many critical genes needed for growth and development are hidden deep within the nucleus and suffer less DNA damage. Ironically, some of the oncogenic driver genes, like BRAF, which when mutated cause melanoma, are located near the nuclear periphery and suffer high levels of UV‐induced DNA damage.

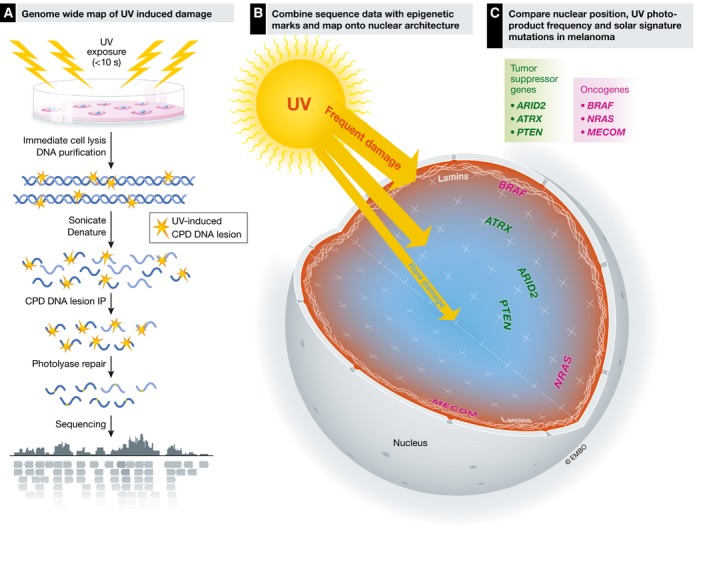

The scientific team, directed by Morrison, first exposed IMR90 human fibroblasts to a large dose of UVC (100 J/m2 of 254 nm light), lysed the cells within seconds to avoid repair, and purified the DNA. They used specific antibodies against the principle UV‐induced photoproduct, the cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer (CPD), to capture damaged DNA fragments which were sequenced and mapped onto the Human Genome version 19. Combining the genomewide CPD data with the extensive chromatin marks data from the Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium indicated that UV‐induced CPDs were non‐randomly distributed across the genome (Fig 1B). Damage was inversely proportional to open or accessible chromatin, and the highest levels of damage were in heterochromatin containing condensed DNase I‐resistant regions. They estimated that 67% of UV susceptibility could be explained by just five histone modifications (H3K4me3, H3K4me1, H3K36me3, H3K27me3, and H3K9me3). For example, H3K9me3 is associated with heterochromatin and, in a key experiment, methyltransferase inhibitors were shown to decrease H3K9me2/3 levels, altering chromatin structure (Kind et al, 2013) and greatly reducing CPDs in these heterochromatic sequences. They also noted that the top 5% most vulnerable regions were enriched in LADs, which included highly repetitive, long interspersed elements (LINEs). Correction for the high dipyrimidine frequencies in LADs revealed that this increase in UV damage was due to the chromatin state and not the nucleotide sequence.

Figure 1. Mapping UV‐induced adducts to the nuclear architecture.

(A) Workflow of the DNA isolation and sequencing (adapted from García‐Nieto et al, 2017). (B) Chrom3D is used to visualize DNA damage data along with epigenetic marks. (C) Analysis of the 3‐dimensional nuclear position of melanoma cancer driver genes with their UV damage load in IMR90 cells. Blue areas indicate lowest levels of damage and red areas indicate highest levels of damage. Tumor suppressor genes (green) that suffer higher than average levels of UV‐induced DNA damage and are mutated in melanoma. Specific oncogenes (magenta), all of which are associated with the nuclear periphery and LADs, have higher lesion frequencies, and are highly mutated in melanoma.

The authors then mapped the CPD distributions onto a 3‐D model of the nucleus using Chrom3D to visualize specific TADs (Dekker, 2016). These amazing images and movies revealed that the radial position of the gene location dictated UV sensitivity—those genomic regions located closest to the nuclear periphery were the most highly damaged regions (Fig 1B). These data nicely confirm their other data showing high rates of damage in LADs. In fact, chromosomes that span the nucleus exhibit gradients of damage, with higher UV‐induced lesion frequency toward the outer edge.

With these molecular maps in hand, the authors navigate potential causes underlying mutations that drive the development of melanoma, a human cancer associated with UV exposure. Sequence data from melanoma have previously indicated a C to T “solar signature” associated with UV‐induced photoproducts. The authors noted a strong positive correlation between accumulation of CPDs in IMR90 fibroblasts with mutations along chromosomes in malignant melanoma. Finally, using a large sequence data set from over 11,000 melanoma samples, the authors found that tumor suppressor genes, including ATRX, PTEN, and ARID2, showed high mutation frequencies in melanoma patients. About 88% showed increased levels of photoproducts in IMR90 cells, and of these, 77% were located within a LAD. Of particular note was the oncogene BRAF, the most frequently mutated driver gene in melanoma (> 60%), which showed the highest susceptibility to UV damage and is located within a LAD (Fig 1C). One wonders, why would BRAF be relegated to such a precarious existence on the nuclear periphery? Is it possible that events that drove the organization of the nuclear genome were selected for by forces that were less about the development of cancer, but more about normal functioning of cellular programs?

Although this was not a study on repair kinetics, as the authors assessed DNA lesion frequencies immediately after damage, they do consider related studies by the Sancar laboratory, which mapped the rates of UV‐induced damage removal by sequencing the short oligonucleotides excised during nucleotide excision repair (Hu et al, 2015; Adar et al, 2016). Unfortunately due to the differences in the way the two large data sets of epigenetic markers were cross‐referenced (ENCODE vs. Roadmap Epigenomics Consortium), a direct comparison is not feasible. However, there is strong correlation between high sites of damage and low rates of repair in heterochromatic regions when the two data sets are compared.

Future studies in molecular cartography could answer many questions raised by this paper. For example, localization of 6‐4 photoproducts that are produced at about 1/3 the frequency of CPDs will provide a more complete view of UV‐induced damage. Another important pursuit will be to make damage maps of the different stages of the cell cycle, as chromatin is highly dynamic and TADs, loops, and compartments are significantly altered through mitosis (Nagano et al, 2017). These would help us understand whether genome stability, due to the inherent nuclear architecture, varies significantly as part of the cell cycle (Nagano et al, 2017). Furthermore, it will be interesting to compare genome landscapes of damage across cell types and even different species. Is the BRAF gene situated in a vulnerable location in all cells in our body? In other organisms? One could follow the nuclear topography and track damage during differentiation from pluripotent stems cells into specialized cells. One can also imagine a time in the near future where damage and repair might be mapped at the genome level in single cells. These data too would allow one to ask whether the act of DNA repair causes large‐scale genomic architecture changes, perhaps pushing the most vulnerable sequences to the interior of the nucleus.

See also: PE García‐Nieto et al (October 2017)

References

- Adar S, Hu JC, Lieb JD, Sancar A (2016) Genome‐wide kinetics of DNA excision repair in relation to chromatin state and mutagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: E2124–E2133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adebali O, Chiou YY, Hu J, Sancar A, Selby CP (2017) Genome‐wide transcription‐coupled repair in Escherichia coli is mediated by the Mfd translocase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114: E2116–E2125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane N (2003) Mercator: the man who mapped the planet, 1st Amer edn New York: H. Holt; [Google Scholar]

- Dekker J (2016) Mapping the 3D genome: aiming for consilience. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 17: 741–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser J, Williamson I, Bickmore WA, Dostie J (2015) An overview of genome organization and how we got there: from FISH to Hi‐C. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 79: 347–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García‐Nieto PE, Schwartz EK, King DA, Paulsen J, Collas P, Herrera RE, Morrison AJ (2017) Carcinogen susceptibility is regulated by genome architecture and predicts cancer mutagenesis. EMBO J 36: 2829–2843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JC, Adar S, Selby CP, Lieb JD, Sancar A (2015) Genome‐wide analysis of human global and transcription‐coupled excision repair of UV damage at single‐nucleotide resolution. Genes Dev 29: 948–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kind J, Pagie L, Ortabozkoyun H, Boyle S, de Vries SS, Janssen H, Amendola M, Nolen LD, Bickmore WA, van Steensel B (2013) Single‐cell dynamics of genome‐nuclear lamina interactions. Cell 153: 178–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao P, Smerdon MJ, Roberts SA, Wyrick JJ (2016) Chromosomal landscape of UV damage formation and repair at single‐nucleotide resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 9057–9062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagano T, Lubling Y, Varnai C, Dudley C, Leung W, Baran Y, Mendelson Cohen N, Wingett S, Fraser P, Tanay A (2017) Cell‐cycle dynamics of chromosomal organization at single‐cell resolution. Nature 547: 61–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Evans K, van Eijk P, Bennett M, Webster RM, Leadbitter M, Teng Y, Waters R, Jackson SP, Reed SH (2016) Global genome nucleotide excision repair is organized into domains that promote efficient DNA repair in chromatin. Genome Res 26: 1376–1387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]