Abstract

Improving outcomes of youth with mental health (MH) needs as they transition into adulthood is of critical public health significance. Effective psychotherapy MH treatment is available, but can be effective only if the emerging adult (EA) attends long enough to benefit. Unfortunately, completion of psychotherapy among EAs is lower than for more mature adults (Edlund et al., 2002; Olfson, Marcus, Druss, & Pincus, 2002). To target the high attrition of EAs in MH treatment, investigators adapted a developmentally appropriate brief intervention aimed at reducing treatment attrition (TA) in psychotherapy and conducted a feasibility study of implementation. The intervention employs motivational interviewing strategies aimed at engaging and retaining EAs in outpatient MH treatment. Motivational enhancement therapy for treatment attrition, or MET-TA, takes only a few sessions at the outset of treatment as an adjunct to usual treatment. Importantly, it can be used for TA with psychotherapy for any MH condition; in other words, it is transdiagnostic. This article presents the first description of MET-TA, along with a case example that demonstrates important characteristics of the approach, and then briefly describes implementation feasibility based on a small pilot randomized controlled trial.

Keywords: motivational enhancement therapy, emerging adults, motivational interviewing, treatment attrition, treatment retention

The Clinical Population and Mental Health Care

Older adolescents who are emerging into adulthood, also commonly referred to as transition-age youth, experience a unique developmental stage (Arnett, 2000). This developmental stage typically begins at age 18 (although it can begin as early as age 14) and continues to age 25 or 30 (Arnett, 2000; Davis, Green, & Hoffman, 2009). Arnett differentiates this stage from that of late adolescence and early adulthood, indicating that the former is characterized by rejection of authority and initial identity formation while the individual is still under the supervision of a parent and the latter is characterized by achievement of adult goals such as having a long-term job, long-term romantic relationship, and possibly children. The interim stage, emerging adulthood, comprises ongoing identity formation while the individual is independent of a parent, and consists of a series of short-term jobs and romantic relationships (Arnett, 2000). The intervention that the authors devised is intended to address this developmental stage, when individuals may still demonstrate rejection or distrust of authority figures and may also have difficulty with being consistent about attending psychotherapy treatment.

Though prevalence estimates vary, using the conservative prevalence estimate of 6.5% of young adults with mental illness (Government Accountability Office, 2008), applied to 2014 Census estimates (http://www.census.gov/popest/data/national/asrh/2014/files/NC-EST2014-AGESEX-RES.csv), indicates that approximately 3.2 million emerging adults (EAs) have a mental illness in the United States. Notably, many mental health (MH) conditions have onset during this age range, and three quarters of all MH conditions have onset before age 25 (de Girolamo, Dagani, Purcell, Cocchi, & McGorry, 2012; Kessler et al., 2007). In addition, findings from some studies of adult interventions have efficacy in older adults but not in those younger than ages 25 or 26 (Burke-Miller, Razzano, Grey, Blyler, & Cook, 2012; Uggen & Wakefield, 2005). Taken together with the legal, health care coverage, and service system changes that typically come with achieving legal adulthood, the stage of emerging adulthood is of great interest when it comes to improving MH care and retention in care. Young people with MH needs during the transition to adulthood can have tremendously compromised functioning in the realms of work, independent living, and staying out of legal trouble (Davis & Koroloff, 2007; Davis & Vander Stoep, 1997; Embry, Vander Stoep, Evens, Ryan, & Pollock, 2000; Newman, 2009; Planty et al., 2008). The majority of youth with a serious MH condition will be arrested by age 25, and most will have multiple arrests, often with serious charges (Davis, Banks, Fisher, Gershenson, & Grudzinskas, 2007; Fisher et al., 2006). Just as EAs in the general population have higher rates of alcohol and drug use and abuse than any other age group (Epstein, 2002), emerging adulthood is the peak age for substance abuse (36%) among individuals with MH conditions (Epstein, 2002; Sheidow, McCart, Zajac, & Davis, 2012). Further, EAs with MH conditions are at high risk for other poor outcomes including homelessness (Embry et al., 2000), unwanted pregnancy (Vander Stoep et al., 2000), school dropout (Planty et al., 2008), and unemployment (Haber, Karpur, Deschênes, & Clark, 2008).

Although office-based MH treatment is accessed by over 760,000 EAs each year (Olfson et al., 2002), its impact is limited because this age group is up to 7.9 times more likely to drop out of treatment than mature adults (Edlund et al., 2002; Olfson et al., 2002). Psychotherapy dropout also contributes to system inefficiencies, expensive psychiatric service utilization, and clinic income loss (Carpenter, Del Gaudio, & Morrow, 1979; Ogrodniczuk, Joyce, & Piper, 2005). It is also associated with lower medication adherence, poorer outcomes, and more distress (Hoffman, 1985; Pekarik, 1992). Treatment dropout has additional consequences in EAs insofar as it blocks support of critical psychosocial development needed for successful assumption of adult roles (Chung, Little, & Steinberg, 2005). The significance of addressing MH conditions at this time of life is clear. Current research suggests a minimum of 11–13 psychotherapy sessions for 50–60% of clients to achieve recovery (Hansen, Lambert, & Forman, 2002; Lambert, 2007). A simple and potentially cost-effective step to improving EA functioning and reducing system inefficiencies is to provide effective treatment attrition (TA) interventions.

Targeting Attrition in Psychotherapy Treatment

There are systems-level barriers to retention (e.g., age-related changes in Medicaid eligibility or clinic coverage), but some barriers may be accessible to therapist intervention. However, the literature on malleable correlates (i.e., factors that can be therapist targets) of TA focuses on children or adults (Block & Greeno, 2011), so little is known about the specific reasons for dropout in EAs. It is likely, though, that they share some of the most common correlates of TA in adults. Poor working alliance is consistently associated with TA and is composed of therapist–client affective bonds and agreement on therapy goals and tasks (Johansson & Eklund, 2006; Lingiardi, Filippucci, & Baiocco, 2005; Meier, Donmall, McElduff, Barrowclough, & Heller, 2006). Alliance may be particularly impeded in EAs because of the developmental stage. Identity formation, which continues into young adulthood and involves rejection of authority (Lodi-Smith & Roberts, 2010), may interfere with therapeutic bonds when therapists are viewed as authority figures, if authority figures endorse therapy, or when EAs disagree with the therapist. Developing confidence in one’s own capacities can lead to resistance of gestures, ideas, or actions from those the EA views as parental or authoritative (as therapists can seem).

In addition, TA is associated with negative or misperceptions about treatment (Dyck, Joyce, & Azim, 1984; Grimes & Murdock, 1989; Kokotovic & Tracey, 1987; McNeill, May, & Lee, 1987), such as the length and efficacy (Edlund et al., 2002; Pekarik & Wierzbicki, 1986; Pulford, Adams, & Sheridan, 2008). A recent review of extant literature on TA in adult psychotherapy made specific recommendations to reduce attrition: pretherapy description and exploration of roles that client and therapist play; use of motivational interviewing; use of a multidimensional approach that increases client choice and planning of therapeutic options; and incorporating client feedback to therapists to guide treatment strategies and serve as an early warning system that a client is thinking about dropping out (Barrett et al., 2008).

Recent reviews report no therapist-implemented psychotherapy TA interventions with efficacy evidence for adolescents (Block & Greeno, 2011; Kim, Munson, & McKay, 2012) and only a small range for adults (Ogrodniczuk et al., 2005; Sims et al., 2012). Establishing attrition efficacy in EAs requires randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of the intervention exclusively in EAs, or conducting age group difference analyses in adult RCTs that include EAs in sufficiently powered sample sizes to detect differences (Davis, Koroloff, & Ellison, 2012). Given the higher dropout rate and developmental uniqueness of EAs, efficacy of adult interventions used for EAs cannot be assumed. Only one therapist-implemented psychotherapy TA intervention has some evidence of efficacy specifically in EAs: motivational enhancement therapy (MET). METs are derived from motivational interviewing (MI), which is an interpersonal style of therapy characterized by affirming client choice and self-direction, using both directive and client-centered components, in the context of a strong working alliance, to resolve ambivalence about the client’s problems, and increase perceived self-efficacy to address the target problem (Miller & Rose, 2009; Söderlund, Madson, Rubak, & Nilsen, 2011). In MI, the therapist is intentionally directive, with a focus on a particular target behavior, using an interviewing style of questioning and clarification statements and attempting to guide the client to resolving ambivalence by having the client explore his or her own thinking and perception. The therapist’s role is therefore transformed from being the expert giving advice into collaborating with the client, learning about the client’s perspective, and having the client take the lead in decision making.

METs are structured MI protocols lasting from one to four sessions and primarily serve as a brief, adjunct intervention at the outset of therapy to increase the subsequent treatment’s efficacy, in part through enhanced treatment retention (Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005). Evidence of MET's attrition efficacy in EAs comes from two small RCTs in narrow clinical populations: postpartum depression (n = 53; Grote et al., 2009) and college students with social anxiety disorder (n = 27; Buckner & Schmidt, 2009). These studies were limited to a single diagnostic category. However, given this promising evidence in EAs, METs are a possible candidate for broader application to retain EAs presenting for psychotherapy for these and other MH conditions (i.e., transdiagnostic).

Not only do METs have initial evidence of efficacy in EAs, but they, as a group, are the most widely used TA interventions in adults (Barrett et al., 2008) and have demonstrated attrition efficacy in a variety of clinical populations. In small RCTs (in addition to the MH populations of EAs described above), METs have shown efficacy for reducing TA in outpatient treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adult veterans (Murphy, 2008) and substance abuse treatment for adults with co-occurring mental illness (Martino, Carroll, O’Malley & Rounsaville, 2000; Steinberg, Ziedonis, Krejci, & Brandon, 2004). METs also reduce adult TA in non-MH populations (e.g., addictions [Carroll, Libby, Sheehan, & Hyland, 2001; Daley, Salloum, Zuckoff, Kirisci, & Thase, 1998] and health [Valanis et al., 2003]). Again, however, studies have been limited to single categories of diagnoses.

METs have many advantages, but the major disadvantage is that each one is designed to address a specific MH disorder (e.g., PTSD) or problem behavior (e.g., substance use); there is no MET used across disorders (see Westra, Aviram, & Doell, 2011). This makes the current array of METs unusable as TA interventions for typical MH therapists who treat a multitude of problems and co-occurring problems, many of which may only be revealed during treatment. That is, typical MH therapists have to work transdiagnostically in their daily work, so it is unlikely they can specialize in TA interventions for a single diagnostic category.

MI/MET as a Transdiagnostic Intervention for Targeting Treatment Attrition

To test a psychotherapy TA intervention that could be broadly used in EAs, we developed an adapted MET (MET-TA) for use regardless of MH condition(s) to specifically reduce TA. Age-related adaptation was unnecessary because MET is age appropriate, as evidenced by the two TA studies in EAs and its attrition efficacy in both adolescents (Stein et al., 2006) and adults (Carroll et al., 2001) in addictions treatments. Rather, the adaptation was to consider TA as the primary problem, as opposed to focusing on a specific MH condition; this is unique compared with other METs. MET-TA applies MI style to target factors associated with TA that are amenable to change: poor working alliance, negative perceptions and misperceptions about treatment or therapists, and attention to treatment progress (Lambert, Harmon, Slade, Whipple, & Hawkins, 2005). A recent meta-analysis of interventions to increase attendance in psychotherapy found that the most effective strategies included several of our targets: motivational interventions, preparation for psychotherapy, and informational interventions (Oldham, Kellett, Miles, & Sheeran, 2012).

MET-TA is primarily a pretherapy intervention, replacing therapists’ usual initial sessions, followed by their usual therapy (i.e., MET-TA can be an adjunct to any other psychotherapy). MET-TA protocols are also implemented when TA indicators arise later in therapy. We chose MET to adapt because (a) it has widely available training and strong quality-assurance protocols and is the most widely implemented TA intervention; (b) it is age appropriate; (c) it has consistent evidence of TA efficacy in individuals with a variety of MH conditions (Westra et al., 2011); (d) meta-analysis of MI found higher effect sizes for minority populations (Hettema et al., 2005), suggesting adaptations for them may not be needed; (e) MI produces strong working alliance (Crits-Christoph et al., 2009; Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Hendrickson, & Miller, 2005), which should reduce TA; (f) its problem-focused elements can specifically target additional TA correlates (described above); (g) MET MI strategies are well specified, brief, and can be added as a pretherapy adjunct to the full array of existing psychotherapies; and (h) it can be paid for by standard health care coverage. Taken together, the evidence suggests an adapted MET will be effective in reducing TA, thus improving the efficacy of subsequent MH treatment (McCabe, Rowa, Antony, Young, & Swinson, 2008; Van Voorhees et al., 2009; Westra & Dozois, 2006), and could be rapidly disseminated.

The authors developed a manualized intervention adapted from three sources (Sampl & Kadden, 2001; Sheidow, 2009; Zuckoff, Swartz, & Grote, 2008), as well as an 8-hour pretraining consisting of viewing segments from MI video trainings and completing a companion guide of short-answer questions (developed by the second author). Answers to the companion guide questions are evaluated by the trainer, with individualized feedback provided to therapists. Following pretraining and video companion guide review/feedback, two 8-hour in-person trainings are conducted 1 week apart to assist therapists in practicing MI strategies and the manualized MET intervention. The nature of the training is similar to that used for other MET protocols (Sampl & Kadden, 2001; Sheidow, 2009). Since favorable outcomes for many evidence-based practices have been attenuated by low therapist fidelity to treatment protocols (Schoenwald, Henggeler, Brondino, & Rowland, 2000), there is a MET-TA quality-assurance protocol that includes weekly group supervision (via telephone) and audiotape review of MET-TA sessions. Telephone supervision is based on therapist descriptions of sessions and the supervisor’s review of taped sessions. Therapists are provided individual, written and verbal feedback through scoring of tapes monthly using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) Scale (Moyers et al., 2005). MET-TA supervisors also are available between supervisions as needed via e-mail/phone, although therapists rarely use this in practice.

Description of the MET-TA Intervention

There are five phases to this TA intervention, as introduced by Zuckoff and colleagues (2008). The phases do not correspond to separate therapy sessions, and could conceivably be included in one single session, depending on the level of therapist skill and client participation. These five phases as applied to MET-TA are (a) elicit clients’ reasons for seeking psychotherapy; (b) explore clients’ histories of distress and coping with distress, previous experience with therapy, and expressed hopes for therapy; (c) provide education about types of therapy, what therapy is like, and how long it may take, and explore problems of early termination; (d) collaborate on problem solving client-identified practical, psychological, and cultural treatment barriers; and (e) based on assessment of client readiness for making a commitment to participate in therapy, negotiate a plan for staying in treatment or attempt to overcome identified barriers. Therapists may then utilize other forms of therapy, as they deem appropriate, to address clients’ presenting problems. During the course of therapy, therapists check with clients as part of the MET-TA protocol to ensure negotiated plans are working, adjusting plans when not. Any period of two missed appointments or 2 weeks without a session triggers revisiting the plan.

In Phase 1, eliciting the story, the therapist’s task is to develop a basic understanding of presenting problem(s). The therapist uses this process to begin forming a therapeutic alliance by ensuring the client feels understood. EAs are particularly likely to be ambivalent about coming to therapy. The therapist’s next task is to elucidate and clarify the nature of any ambivalence toward engaging in therapy. Some of the MI skills used during this phase include the skillful use of open-ended questions to elicit the client’s story, empathic reflections and facilitative comments to continue to build alliance, summaries to ensure understanding of the story as the client sees it, and support and reflection of any client statements that indicate movement toward change. For the latter, the aim is to elicit discussion about the importance of change in the client’s current situation, listening specifically for the client’s perspective on how he or she is suffering, what he or she believes is contributing to this suffering, and how it interferes with daily life.

Perhaps the most important therapist skill to develop is that of resisting the “righting reflex,” the desire to try to fix the situation by making suggestions or giving advice. The righting reflex is essentially the therapist arguing for change, which paradoxically leads to the client’s defending his or her position. The goal of MET-TA is to lead the client to argue for change, which improves client follow-through on a plan. In the event a client is not ambivalent about engaging in therapy, the therapist’s task is to identify the most compelling reasons making the client desire therapy. These reasons may be useful later in therapy if ambivalence arises and MET-TA is needed to improve engagement. Even if a client does not present initially with ambivalence, the phases described here are completed, although it is briefer since it is a validation of the client’s perspective and simply ensures that the client has a plan for any future barriers to treatment retention.

Session Examples of MET-TA Phases

Example session dialogues (highlighting the specific MI strategies used) are provided in tables to elucidate each MET-TA phase.

During the initial session, the therapist begins in Phase 1 by eliciting the client’s story. Table 1 provides a case vignette of this phase with a 19-year-old client struggling to complete high school and start working. The client’s mother referred her for outpatient therapy, and the client came reluctantly, as she had previous experiences with therapy when she was younger that she felt were unhelpful. The therapist’s goals are to thoroughly understand the problem that brings the client to therapy at this time and to foster an atmosphere of collaboration. The therapist does this by using affirmations, reflections, and open-ended questions to encourage the client to elaborate. Motivational techniques emphasize supporting the client’s autonomy as much as possible, which is one of the reasons MET-TA fits the needs of EAs so well. As the therapist begins to understand the presenting problem more clearly, she uses a transitional summary into Phase 2, acknowledging the client’s ambivalent feelings about therapy. She helps the client see the discrepancy between a desire to finish school and get a job and not seeking help for disabling symptoms of anxiety.

Table 1.

Example of MET-EA Phase 1: Eliciting the Story

| Dialogue | MI Strategy |

|---|---|

| THERAPIST (T): Thanks for filling out our intake information. This will be helpful—we’ll go over these a little later so we can consider it together and I can understand your background info and history a little better. Before that, it would help me a lot if we could talk about how things are going for you in the present. | Beginning with an affirmation, then an open-ended question to draw out the story |

| CLIENT (C): My mom was the one who wanted me to come here today. I guess that’s okay. But she’s driving me crazy and doesn’t get me at all. She thinks I’m using my anxiety as an excuse and she tells me I need to get my act together and I need to get over it. Meanwhile, I’m trying to finish school and start a new job. It’s a lot to do, and to make me even more anxious, I now have to come to therapy too, and therapy never really helps. | |

| T: You feel your mother doesn’t really understand the stress you’re facing and that you’re working on accomplishing a lot of important things despite feeling pretty anxious. | Therapist reflects meaning and feelings |

| C: Yes, it’s really pissing me off. I don’t even want to talk to my mom sometimes. | |

| T: This is really useful in helping me understand where you’re coming from. I was wondering if you could tell me what else you have been feeling and doing during this time when things seem so stressful. | Asking for elaboration and problem recognition |

| C: Well I’m anxious like all the time, so I’m trying to ignore my mom. I try to use so-called coping skills that counselors have told me to use, but none of it works, you know. The other day I had a panic attack and my mom actually yelled out “Call 911, she’s going to have a heart attack and die!” Is that helpful?! You’re not supposed to say something like that when someone is having a panic attack! Come on! | |

| T: You’re feeling frustrated about not getting support. Your mom sometimes makes you feel more anxious by not doing the right thing when you need her help. | Reflective summary of complaints |

| C: Yes, my mom is making it worse. My anxiety is horrible; I can’t stand it. | |

| T: And this is a change from how things have been in the past? | Looking back |

| C: It’s gotten worse this year when I started trying to finish school and start a job. I really want to get into nursing school. | |

| T: And here you are, doing your best with a lot of new challenges, and people who are supposed to help aren’t feeling very helpful to you. | Affirmation and identification of possible engagement barrier |

| C: And before that things weren’t too great either. I’ve always had problems with anxiety, but it feels worse now. Then my mom’s intolerable. Maybe she should be in therapy instead of me! | |

| T: You are really doing your best to manage your anxiety—getting your school and work goals accomplished all by yourself—but you are feeling misunderstood by your mom and you would really like some more support. | Affirmation and complex reflection |

| C: Yeah, exactly. No one seems to understand what this is like for me, except maybe some friends. | |

| T: You feel alone dealing with this stress. | Empathizing |

| C: My mom thinks I should just get over it, and therapists just give you these cute little coping skills. But I need to get my anxiety under control. | |

| T: So how did you make a decision to come here today? Dialogue | Eliciting the ambivalence and possible barriers to treatment MI Strategy |

| C: My mom told me to come. I should just get a job and get over this anxiety . . . I don’t know if I’m ready to work, but I really want to . . . There’s just too frickin’ much. | |

| T: How did you make your decision to start your new job? | Eliciting more detail and possible dilemma |

| C: Well, even though I’ve been struggling with anxiety for a long time, I want to be a nurse. I love working with the elderly and that makes me feel good; I enjoy it. It gets my mind off my problems. I want my mom and others to take me seriously. | |

| T: Let me see if I understand the situation. You’ve been dealing with anxiety for a long time and even before the past year. You’ve had counseling for anxiety before, but it really hasn’t been helpful. But now you’re really interested in starting a job and finishing school so you can achieve your ultimate goal of becoming a nurse. What gets in the way is that you’re struggling with the stress and anxiety, and your mom doesn’t understand it is a real problem and that you’re doing your best. You want to move forward with your goals because they’re important to you. It would be nice to have some support and to feel understood. | Transitional summary including acknowledgment of feelings, personal goals, and interest in receiving help |

| C: Yep, you got it. Jeez, no matter what I do I can’t win. | |

| T: And you are at a point now where you would like some help with your anxiety. At least, you want to make sure you get some help with some of the challenges you’re facing right now. | Implicit recognition of need for change |

| C: Yes, I’m worried everything is going to be too much. | |

| T: You’re not sure you can succeed at all of the things you want to do. | Acknowledgment of feelings |

| C: Right. I don’t know how I’m going to keep it all going in the right direction. |

Phase 2 explores clients’ histories of distress, coping, and treatment, and any current hopes for treatment. After eliciting the story, the therapist further investigates experiences with, beliefs about, and hopes for what treatment can accomplish. This entails understanding whether the client has experienced similar problems in the past and what coping mechanisms the client was able to use. Emphasizing past successes increases the client’s self-efficacy, a core MI principle. The therapist specifically inquires about psychotherapy experiences, both good and bad (including attrition). Since EAs are very focused on peer approval and since seeking treatment can be stigmatizing, it is especially important to understand the client’s views, as well as attitudes of friends and family, toward MH care. Key strategies used during this phase include increasing ambivalence about coming to therapy by developing a discrepancy between the client’s values and goals versus not engaging in treatment. This is done by identifying spontaneous talk about making changes, as well as strategically eliciting such “change talk” from the client. In MI, change talk is statements indicating the desire, ability, reason, or need to change. The therapist selectively reinforces the change talk using reflections.

At the end of this phase, the therapist seeks information about the client’s view of what therapy will be like, how long he or she thinks it will take, and what he or she expects to be different as a result. The therapist elicits both positive (leading to attendance) and negative (leading to ambivalence or attendance barriers) perceptions, using empathic reflection to convey a nonjudg-mental understanding of negative feelings and/or beliefs about treatment. Finally, the therapist asks about hopes and fears pertaining to treatment. Encouraging clients to describe what they do and do not want from treatment (and from the therapist) is a relatively unusual thing to do, but it is one element that can have the most powerful effect on engagement. Furthermore, looking forward to what could be different at the end of treatment can further invoke hope that things can get better and that treatment can play an important role in improvement. An example session dialogue is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Example of MET-EA Phase 2: Exploring the Client’s Histories of Distress, Coping, and Treatment, and Any Current Hopes for Treatment

| Dialogue | MI Strategy |

|---|---|

| THERAPIST (T): [Following client’s description of conflict with her friends] So this has been an awful way to feel, so angry and hopeless and just stuck in this situation with your friends. Have there been times in the past when you felt like you’re feeling now? | Asking for history of specific illness |

| CLIENT (C): Well, sort of. We’ve had lots of fights before, and we always kind of made up. But this is just so much worse, and I don’t want it to keep going like this. | Change talk; desire to change |

| T: You expect to have difficult times in your life and then for things to get back to normal, but this time they don’t seem to be getting back to normal. | Reflection |

| C: Yeah, I can usually pull myself out of it. | |

| T: How have you done that? | Asking about past coping |

| C: Well, I don’t know. I guess I’ve had my friends to talk to, to kind of bounce thoughts off. But I’ve been so alone lately and my friends don’t seem to be around anymore. No one really cares or understands what’s going on. | Identifying interpersonal contributors to current episode |

| T: You feel like there is no one to turn to at this point when you are feeling the most frustrated and down, and you need someone to understand you or offer you a little support. That’s the big difference between now and before—you don’t have anyone to turn to who could help. | Reflection of meaning and a subtle reframe |

| C: I hadn’t really thought about it that way. Yeah I don’t have anyone now who I can really talk to. | |

| T: And you miss that and you’re really feeling the need for that now. | |

| C: I’ve got to do something. I can’t go on feeling like this anymore. | Change talk: need to change |

| T: You said your friends could understand you. What was it about them that seemed to make you feel understood? | Reflection—asking for elaboration |

| C: Well, you know, they would sit and take time to listen to me vent. They really seemed to care and wanted to know what was going on. They were interested. | Giving therapist information about what client is looking for in therapist |

| T: You could be yourself with them. | Reflection of meaning |

| C: Yeah, I guess so. | |

| T: Your friends listened, they wanted to help, and they seemed to care about you. They wanted to help you feel better. | Interim summary |

| C: Yeah, they wouldn’t be all judgmental and tell me what I should be doing. | Key point about what she does and does not want |

| T: You want to figure things out yourself. | A specific reflection highlighting the key point |

| C: Uh huh. I want to make sure no one else decides for me what I should do. Like, I had this friend who went to counseling for depression, and they put him on some kind of meds that made him gain all this weight. He was sort of a zombie. I don’t want to end up like that. | Revealing a barrier—negative treatment expectations |

| T: So you want to make sure you know what your options are and the possible things that could go wrong. | Reflection of feeling |

| C: Yeah. Like I wouldn’t want to take meds. They tried to put me on stuff when I was a kid and I flushed it down the toilet. | |

| T: You really felt like it was forced on you. (Client nods.) So you’ve seen two different kinds of help that people get. One is medication, which doesn’t feel right to you. On the other hand, there is having someone to talk to, who understands and seems to care and wants to help, like it was with your friends—that feels like it could be helpful. | Reflection of feeling; linking summary and reframe |

| C: Yeah, it sounds like it could be. | Change talk |

| T: So if you were to come to therapy, how long do you imagine it will take for us, like how many sessions or weeks, to get to the point where you’re talking things through in a way that you’re starting to feeling better? | Specific question about client’s perception of how long therapy will be |

| C: I don’t know . . . like a couple months maybe? I don’t really know what you do here, exactly. | |

| T: Well, what we offer is called “cognitive-behavioral therapy.” It’s a type of talking therapy that focuses on dealing with your specific problems and the thought processes you experience and how that relates to your depression. The therapist will be in your corner, listening to you and helping you figure out what you can do to make things better. | Introducing the treatment |

| C: That sounds good. I could use some help with my problems. | Change talk |

| T: Looking down the road months from now, if the therapy works and is really helpful for you, how will things be different? | Looking forward |

| C: Well, I would really like to have a better relationship with my friends and not be fighting all the time, but that seems so impossible right now. | Expressing ambivalence |

| T: Having your friends back is something you would really like, but you can’t quite imagine that happening right now. | Double-sided reflection |

| C: Yeah. I suppose if I weren’t so tired and depressed all the time, my friends wouldn’t be avoiding me so much. And I wouldn’t be picking fights with them about stupid stuff. | Change talk—thinking about possible solutions |

| T: So if things went really well with the therapy, one change would be that you would somehow be less irritable and your friends would want to hang around you more. | Highlighting a source of hope through reflection |

| C: Yeah, and I could talk with them and not feel so isolated all the time. | More change talk |

| T: The way you are feeling now, it doesn’t seem like there is any way you could do this, but if things went well and you had more energy, you could figure out how to be less angry and stop driving your friends away so much. | Reframing from pessimism to hope |

| C: Yeah, it would be really great if therapy could help with that. | Envisioning help |

In Phase 3, providing feedback and education, the goal is to offer education about therapy generally, including specifics about typical time frames, costs, expectations for improvement, or techniques that might be used. The pros, cons, limitations, and benefits of therapy are included. Therapists may also offer education about diagnosis, if possible normalizing it for the client. The therapist reframes problems as treatable conditions rather than as hopeless situations, failure of will, or lack of ability. The therapist can point out that therapy often helps people see alternative solutions to what had previously seemed like unsolvable concerns or situations. A key principle, though, is that the therapist always asks permission before offering information. This process facilitates a collaborative setting, making it more likely that the client is open to what the therapist says and reducing the likelihood of resistance. By eliciting what the client already knows about therapy, providing objective information, and asking for a reaction, the therapist shows respect for the client’s views and acknowledges the client’s power to determine what he or she does with the information. This practice tailors the feedback and psychoeducation to the client’s individual concerns and knowledge. If the person objects to certain language or expresses uncertainty as to whether therapy is needed, the therapist’s job is to recognize the ambivalence and respond empathically and nondefensively. While inquiring about the client’s perspective and emphasizing its legitimacy, the therapist simultaneously looks for opportunities to connect issues identified by the client with the therapist’s ability to help (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Example of MET-EA Phase 3: Providing Feedback and Education

| Dialogue | MI Strategy |

|---|---|

| THERAPIST (T): You filled out questionnaires that can help us see in what ways you may be anxious and whether you seem to be depressed. I’d like to review how you answered so we can talk about it together and see what your thoughts are. Would that be okay? | Brief structure and introduction; asking permission |

| CLIENT (C): I guess that would be all right. | |

| T: Okay, and as we go through it please let me know if it sounds right for you. I want to make sure that I am understanding what you think is going on. The first questionnaire you answered helps us see if you are depressed or not. You scored in the range that we often consider someone to be depressed. For example, you said you often feel tired, have some difficulty sleeping, and don’t enjoy things as much. Tell me a bit more about how some of these things are affecting you. | Inviting active participation, providing feedback, and asking for elaboration; note last sentence is considered an open-ended question |

| C: Well, I feel so stressed out all the time, that I really can’t enjoy anything. Work is probably the thing I enjoy the most because I can get my mind off my own problems. But since I don’t sleep well, I feel tired all of the time. I worry about things all night, so I get on my computer and I start e-mailing or texting my friends. That helps. | |

| T: So you’re tired a lot, at least partly because you can’t sleep well at night. It also sounds like your stress is pretty bad at night and getting in the way of your rest. | Clarifying symptoms |

| C: I am basically a vampire, up all night. An anxious vampire. I don’t know why I can’t sleep. It’s such a problem. | |

| T: Sleep difficulties are often seen in depression, but we also see that people with anxiety can worry a lot at night, which may lead to problems sleeping. It’s also common to see depression and anxiety happening at the same time. Both depression and anxiety can affect feelings and thoughts and make things seem less interesting. Tell me a bit more about not enjoying things as much. | Offering information |

| C: Well, things are so stressful and at times I just feel like being alone and not dealing with anyone. It seems weird because I also still want to go to work, but I guess I just want to avoid all the problems that are always running through my head. In the end it makes things less fun. | |

| T: Sitting alone with all of your anxious thoughts is pretty tiring. It’s better to try to keep busy. | Collecting summary and reflection |

| C: Yes, it’s much harder, the anxiety part. It’s much tougher this year. There’s so much for me to get done. | |

| T: You’re overwhelmed. | Reflection of feeling |

| C: Yes! Isn’t that horrible? I am such a loser sometimes. I can’t deal. | |

| T: You’re really doing your best to manage your anxiety and depression, and you’re really making an effort. But when people are depressed and anxious, we often feel and act in ways that make us unhappy and frustrated. When people have the types of problems you describe like sleep problems, worries, and low energy, we usually think they have depression or anxiety, or both, and that they might need some help to stay on track. That may be what’s going on now, and the added stress of transitioning out of school and into work can make things feel worse, even if you are looking forward to the change. What are your thoughts on that? | Supportive statement and reframing her mood in terms of medical model, then eliciting her reaction; note open-ended questions; note framing in medical model without seeming too “pathologizing,” which might seem negative to EAs |

| C: Well it is pretty stressful, that’s for sure! I just can’t deal with it I guess. | |

| T: This is a challenging time and it can feel like you’ll never dig your way out. | Rolling with resistance via reflection |

| C: Yes! I could really use some help from my parents, but I’m not holding my breath. Maybe if I had support from them—or someone—I would feel better. | |

| T: That makes sense. When things are stressful, it is a good thing to feel helped or supported. Stress can make both depression and anxiety worse, and getting support—especially from our family—can be helpful. I think that’s consistent on how we see things. What do you think? | Supportive and reframing to medical model; note open-ended question |

| C: So can the depression and anxiety get better? Because I don’t think the stress is going to go away. | |

| T: Well, I believe your situation feels pretty bad for you. When you’re depressed or feeling really anxious, everything can start to look overwhelming very quickly. It feels like things are just too much to handle. It’s also harder to find solutions to problems, and it’s likely that you will feel frustrated with yourself and others. As you become less depressed, you may feel stronger or more able to deal with difficult situations, even if the problems or stressful situations don’t change right away. We do find that depression and anxiety can get better. | Reframing without minimizing difficulty of situation; reframing to medical model to respond to question |

| C: Well, I can use some help to feel better. It’s pretty stressful, and I need some help to get through it better. | Adherence talk |

| T: The good news is that we can provide help for your depression and anxiety, we can look at what has and hasn’t helped in the past, and we can offer some options that might help. You can then start to feel a little less overwhelmed and more able to do the things you find important, while feeling less stressed. | Offering hope |

| C. That would be great if it worked. |

Phase 4 consists of problem solving practical, psychological, and cultural treatment barriers. At this point, the therapist discusses the risks of early dropout and a desire to engage the client directly in evaluating and discussing this. The first step is to discuss engagement risks specific to the client and problem solve with the client. In Phase 5, the client and therapist develop a plan that outlines when the issues would be raised again, but the goal in Phase 4 is to draw out, explore, and problem solve unaddressed barriers that could potentially keep the person from engaging in treatment. In some cases, the client will not offer barriers. In this instance, the therapist may ask permission to suggest some that are typical. For example, after asking permission to offer suggestions, the therapist might say, “Some people have told me that even though they wanted to come for therapy, it is hard to find the time or money. Others have worried about what therapy would be like. It wouldn’t be unusual if you had some doubts like these.” Clients may also be concerned whether a therapist who differs from them racially or ethnically, or in gender, age, or social status, can really understand their lives. Trying to elicit these potential barriers from the client while remaining nondefensive, resisting the righting reflex, and remaining open to the client’s worries can often diffuse these concerns. The therapist then works with the client to resolve these barriers, asking for the client’s own ideas about how to overcome the barriers. If the client finds it difficult to imagine overcoming the barriers, the clinician responds empathically, exploring both sides of the client’s ambivalence, offering alternative perspectives, and emphasizing the client’s autonomy in making any decisions. Throughout this phase, the therapist continues to elicit and selectively reinforce any change talk related to the client staying in therapy, moving toward Phase 5, in which the client starts talking about commitment to staying in therapy. Illustrative dialogue for this phase is in Table 4.

Table 4.

Example of MET-EA Phase 4: Problem-Solving Practical, Psychological, and Cultural Treatment Barriers

| Dialogue | MI Strategy |

|---|---|

| THERAPIST (T): If you decide to come to therapy, what could make it hard to stick with it? | Open-ended question to elicit barriers |

| CLIENT (C): Well, I would be kind of embarrassed if my friends found out I was seeing a shrink. | A psychological barrier |

| T: There’s something stigmatizing about getting help from a counselor. Tell me more about what they might think. | Reflection and asking for elaboration |

| C: They would think I was crazy or something. | |

| T: And that would drive them away even more. | Reflection |

| C: And then I have lots going on and things to do that would make it hard to get here. | A potential practical barrier |

| T: The last thing we want to do is interfere with your important activities. I bet we could get creative and work together to figure out a schedule that works for you. About the stigma, though, when you imagine how you would deal with your friends finding out you were getting help, what comes to mind? | Reflection of meaning; problem solving the practical barrier first; then returning to the psychological barrier, asking for specifics |

| C: I don’t know. I guess I’ve seen people make fun of people who are seeing a counselor, like they’re mental or something. T: So on the one hand, you’re thinking this therapy stuff might have something to offer you; but on the other hand, you’re worried people would think something was really wrong with you and they might make fun of you. | Double-sided reflection to capture the ambivalence |

| C: Yeah. | |

| T: What ideas do you have for dealing with that if it happens? | Eliciting client’s ideas first |

| C: (shrugs shoulders) | |

| T: Can we consider what you think other people your age may have done to deal with this barrier? | Asking for permission |

| C: Okay, I guess. | |

| T: What are some strategies you think other people have gotten around having people know that they are going to counseling? | Another way of eliciting client’s ideas, using an open-ended question |

| C: I guess they just hide it, they don’t let anyone know. | |

| T: How would you feel about using that strategy? | Eliciting more about the idea |

| C: I think that would be kind of okay. I think it’s kind of fake, but I guess you have to do what you have to do. | |

| T: So sometimes keeping things private, like the fact that you are going to counseling, is an option even though it seems dishonest. Perhaps it would be okay to do that if it helped you go to counseling when you felt you needed to. | Reflection with eliciting clarification |

| C: Yes, sometimes it’s just no one else’s business. | |

| T: Sometimes you have to use strategies like keeping things private so that you can do things you need to do that others might not approve of or see as normal. | Reflecting meaning, importance of trying counseling |

| C: Yep. |

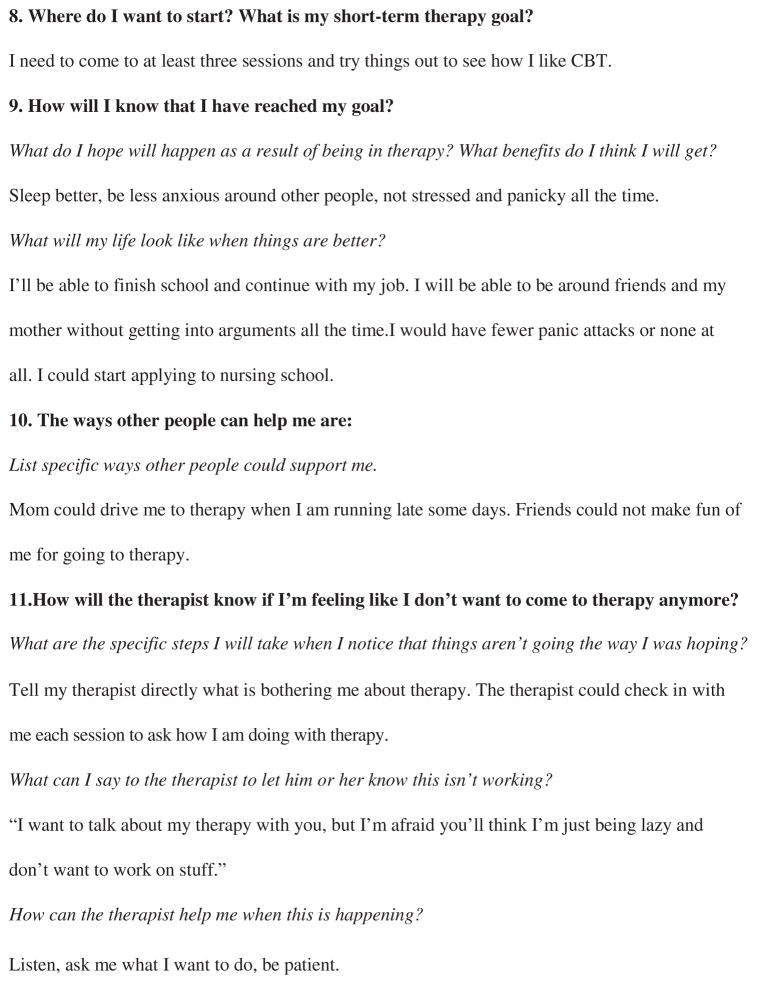

In Phase 5, eliciting commitment or leaving the door open, the therapist’s focus shifts from enhancing motivation to eliciting commitment to staying in treatment (see Table 5 for dialogue example). The therapist summarizes the client’s story and ambivalence about treatment, highlights change talk, outlines next steps, and seeks to elicit commitment. The therapist gauges the client’s level of commitment to moving forward in part by asking a key question such as “How are you feeling about taking that chance to engage in therapy right now?” If the client indicates an intention to move forward, the therapist uses a template to craft an individualized therapy plan in collaboration with the client. If the client remains ambivalent, the therapist does not insist, but “leaves the door open”—that is, the therapist moves back to eliciting reasons for change, relying on the client’s earlier statements about goals the client wants to achieve. The therapist would attempt to engage the client enough so that the client would at least feel comfortable returning for another session. This process may include restating the client’s strengths and likelihood of benefiting from therapy as well as supporting the client’s right to make decisions about his or her life. The therapy plan is a key component of this intervention, as it pulls together all of the work the therapist and client have done together and puts it in the form of a contract that can be referred to in the future and modified as needed. Figure 1 lists the elements that the plan documents and provides an example using the client in the Table 1 dialogue. Importantly, the plan asks the client to identify how the therapist will know that the client is thinking about stopping therapy and ways the client and therapist might address this. After completing the therapy plan, the client and therapist review the plan every 4 weeks and after any period in which the client misses two or more appointments. In reviewing the plan, the therapist and client see what, if anything, needs to be modified to accommodate the client’s needs related to treatment retention.

Table 5.

Example of MET-EA Phase 5: Eliciting Commitment or Leaving the Door Open

| Dialogue | MI Strategy |

|---|---|

| THERAPIST (T): [Summary of the client’s story/dilemma, strengths, desires, abilities, reasons/need for change, feedback on specific illness(es), perceived barriers and disadvantages to treatment, perceived positives of treatment, and resolution of ambivalence toward treatment engagement.] | Summarize |

| Is that a fair summary? | |

| CLIENT (C): Yeah, I think it is. (pause) I would be taking a chance. I guess. | Therapist assessment of the statement is that client is lukewarm, not quite making a commitment |

| T: How are you feeling about taking that chance right now? | Key question |

| C: Well, I need to find a way to get around some of the problems I’ve got. If it keeps on going like this, I’m gonna, you know, start cutting again or something. It’s at least worth trying this therapy stuff. | Commitment talk |

| T: There’s a part of you that feels like you’re taking a chance here, but at the same time, it feels like not taking that chance might be even more risky for you. | Double-sided reflection, ending with a gentle reframe |

| C: Right. I can’t afford not to, so it’s worth taking a chance. | |

| T: Great. So are you ready to figure out a game plan for giving this a chance and making it work better for you than the therapy experiences you’ve had in the past? | Transitioning into developing therapy plan |

Figure 1.

Example of MET-TA therapy plan.

Pilot Feasibility Study of MET-TA

A pilot study evaluated the clinical implementation of MET-TA and the feasibility of the research methods to conduct a future RCT with this population. As the study was insufficiently powered to determine the effect of MET-TA on TA itself, we only describe key aspects of the study that demonstrate the feasibility of implementing MET-TA in community MH centers as well as observations regarding therapist fidelity to the model. Feasibility research is particularly critical given the current dearth of research for this age group.

Methods

Participants

MET-TA was implemented in four community MH centers in Massachusetts. These clinics serve primarily Medicaid or CHAMPUS clients (69%) with a variety of MH conditions. The office-based outpatient therapists represent a wide range of therapeutic orientations and employ a variety of therapeutic approaches, including cognitive-behavioral therapies, psychodynamic therapies, and solution-focused therapies. All therapists in these programs were full- or part-time licensed MH counselors, with master’s or doctoral degrees in a clinical field. Therapist training in these various modalities ranged from brief exposure in continuing education programs to in-depth training with fidelity assurance procedures. However, no distinct TA interventions were used.

Therapist participants were randomized to intervention provision condition (MET-TA vs. usual services) using block randomization by gender (50/50 split) within clinic for each of the four clinics in the study (i.e., four separate randomizations). Four male therapists and six female therapists were recruited. One female usual-services therapist dropped out before she had been assigned a study client and no replacement therapist was available. Therapists assigned to the MET-TA condition were subsequently trained and supervised in provision of MET-TA, as described above. All study therapists received training in procedures to digitally record sessions with client participants, procedures for uploading the recordings, and directions for completion of data collection forms.

Client participant eligibility included ages 17–25, requesting and appropriate for individual psychotherapy for a MH issue, and having appropriate health care coverage to be seen at the clinic. The age was allowed to span higher (>25 but <30) for two participants to accommodate the needs of the clinics in the study. Nine client participants were assigned to MET-TA therapists and nine client participants were assigned to usual services therapists. Participant demographics generally reflected the demographics of central Massachusetts, and there were no significant differences in any baseline variables (e.g., age, baseline symptom level) among client participants assigned to MET-TA therapists or usual services therapists.

Quality-Assurance Procedures

Consistent with standard MI practice, MET-TA clinical supervision included weekly group supervision via telephone and monthly audiotape review. The first author, with consultation with the second author, served as trainer and clinical supervisor for the MET-TA intervention, and is trained in both MI and MI supervision by the primary developers of MI and the MITI (i.e., Miller, Rollnick, and Moyers; Moyers et al., 2005). Initially, only MET-TA therapists with active cases were included in group supervision. However, low caseloads caused by client participant recruitment challenges produced sustained periods without any client participants in therapists’ caseloads. Supervision was thus altered to maintain therapists’ MI skills by including all MET-TA therapists in weekly supervision. This alteration was well received by therapists.

Fidelity Measurement

Two trained coders, one of whom was blind to therapist assignment, coded session tapes for MET-TA fidelity using the MITI Scale (described above) for session audio recordings (Moyers et al., 2005). Interrater reliability for each of the MITI subscales and for the Global Spirit Rating (the primary MITI Scale measuring fidelity) was 80% agreement. Tapes were collected and coded from the initial first and second therapy sessions of client participants, as well as from sessions immediately following any 2-week break in therapy.

Results

Therapist Recruitment

A small number (two to three per site) of therapists volunteered to be a study therapist (recruitment rate across sites = 11.1–50.0%). Study therapists were paid by the grant for their training, supervision, and research paperwork time and received free continuing education units for the 24 hours of MET-TA training. However, subsequent discussions with site supervisors identified the following therapist concerns: finding time to complete the 24 hours of training, clinics not counting training and supervision time toward productivity requirements, and therapists feeling overwhelmed with current demands.

Fidelity of Implementation

Digital recording collection rates by therapists were high. Therapists collected and submitted adequate recordings for fidelity to be evaluated—that is, most client participants (73%) had a digital recording from the first two therapy sessions, with 100% recording of sessions following a 2-week or longer break in therapy. The median Global Spirit Rating (the MITI measure of overall demonstration of adherence to the “spirit” of MI and a good indicator of fidelity to the practice) of usual services therapists was 3.0 (range = 1–4). Fidelity scores were acceptable (score of 4 or higher) in four of the five MET-TA therapists, with a median Global Spirit Rating of 4.0 (range = 4–5) among the four therapists. The fifth MET-TA therapist had unacceptable scores (mean = 2.3, range 2.0–2.6); in the conduct of clinical supervision (i.e., reviewing tapes and conducting supervision) the clinical supervisor also found this therapist consistently nonadherent and not amenable to improving adherence. When the nonadherent therapist’s scores were excluded, MET-TA therapists had significantly higher fidelity scores than usual services therapists (Independent Samples Medians Test p < .02). Thus, therapist participants were relatively willing to abide by the quality-assurance procedures, most were responsive to training and supervision, and the quality-assurance system (including the training and supervision protocol) was effective in generating fidelity to MET-TA.

Discussion

Improving psychotherapy treatment retention in EAs is critical to reduce system inefficiencies, use of more expensive psychiatric services, and poor outcomes. EAs are far more likely to drop out of essential psychotherapy services than children or adults, and current psychotherapies are not designed to address the issues related to treatment retention in this population. The MET-TA described here was crafted specifically to target known and suspected impediments to EA treatment retention, using a brief, cost-effective intervention that could be provided as an adjunct prior to the start of any form of psychotherapy. The intervention is unique in that it is the first MET that the authors know of that is transdiagnostic, and so could easily be used for EA clients with any MH diagnosis. This reduces the need for multiple staff trainings in several different psychotherapy protocols in order to ensure that all diagnostic categories are covered. The pilot study conducted demonstrates that, when training and supervision protocols are utilized, acceptable implementation of the intervention can be achieved in community MH centers by typical MH therapists. The fidelity measure showed differentiation between usual services and MET-TA therapists, and between therapists within MET-TA identified by training protocols as nonadherent versus adherent.

These feasibility results also suggest several desirable design changes for future research. Future therapist recruitment will be maximized by reducing the burden of study participation on study therapists. Specific strategies to reduce therapist participation burden need to be assessed in close collaboration with clinics to determine what is feasible (e.g., counting research activities toward productivity) while also appealing to therapists (e.g., free continuing education credits). Funding for protected therapist caseloads and time for supervision, training, and completing research forms should reduce clinic productivity concerns, enhance therapist recruitment, and accommodate client-based randomization. The next step in testing the MET-TA model is to determine if an RCT powered sufficiently will reveal a significantly higher rate of retention of young adults in psychotherapy in the MET-TA intervention compared with those receiving services as usual.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by award RC1MH088542-02 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Lisa Fortuna and Rich Rondeau.

Contributor Information

Lisa A. Mistler, University of Massachusetts Medical School

Ashli J. Sheidow, Medical University of South Carolina

Maryann Davis, University of Massachusetts Medical School.

References

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood. A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. The American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett MS, Chua WJ, Crits-Christoph P, Gibbons MB, Casiano D, Thompson D. Early withdrawal from mental health treatment: Implications for psychotherapy practice. Psychotherapy. 2008;45(2):247–267. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.45.2.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block AM, Greeno CG. Examining outpatient treatment dropout in adolescents: A literature review. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2011;28(5):393–420. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Schmidt NB. A randomized pilot study of motivation enhancement therapy to increase utilization of cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47(8):710–715. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke-Miller J, Razzano LA, Grey DD, Blyler CR, Cook JA. Supported employment outcomes for transition age youth and young adults. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2012;35(3):171–179. doi: 10.2975/35.3.2012.171.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter PJ, Del Gaudio AC, Morrow GR. Dropouts and terminators from a community mental health center: Their use of other psychiatric services. Psychiatric Quarterly. 1979;51(4):271–279. doi: 10.1007/BF01082830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Libby B, Sheehan J, Hyland N. Motivational interviewing to enhance treatment initiation in substance abusers: An effectiveness study. American Journal on Addictions. 2001;10(4):335–339. doi: 10.1080/aja.10.4.335.339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung HL, Little M, Steinberg L. The transition to adulthood for adolescents in the juvenile justice system: A developmental perspective. In: Osgood DW, Flanagan DW, Foster EM, editors. On your own without a net: The transition to adulthood for vulnerable populations. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 2005. pp. 68–91. [Google Scholar]

- Crits-Christoph P, Gallop R, Temes CM, Woody G, Ball SA, Martino S, Carroll KM. The alliance in motivational enhancement therapy and counseling as usual for substance use problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(6):1125. doi: 10.1037/a0017045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley DC, Salloum IM, Zuckoff A, Kirisci L, Thase ME. Increasing treatment adherence among outpatients with depression and cocaine dependence: Results of a pilot study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155(11):1611–1613. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Banks SM, Fisher WH, Gershenson B, Grudzinskas AJ. Arrests of adolescent clients of a public mental health system during adolescence and young adulthood. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58(11):1454–1460. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.11.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Green M, Hoffman C. The service system obstacle course for transition-age youth and young adults. In: Clark HB, Unruh DK, editors. Transition of youth and young adults with emotional or behavioral difficulties: An evidence-supported handbook. Baltimore, MD: Brookes; 2009. pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Koroloff N. The great divide: How mental health policy fails young adults. In: Fisher WH, editor. Research on community-based mental health services for children and adolescents. New York: Elsevier Science/JAI Press; 2007. pp. 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Koroloff N, Ellison ML. Between adolescence and adulthood: Rehabilitation research to improve services for youth and young adults. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2012;35(3):167–170. doi: 10.2975/35.3.2012.167.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Vander Stoep A. The transition to adulthood for youth who have serious emotional disturbance: Developmental transition and young adult outcomes. Journal of Mental Health Administration. 1997;24(4):400–427. doi: 10.1007/BF02790503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Girolamo G, Dagani J, Purcell R, Cocchi A, McGorry PD. Age of onset of mental disorders and use of mental health services: Needs, opportunities and obstacles. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 2012;21(1):47–57. doi: 10.1017/s2045796011000746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyck RJ, Joyce AS, Azim HF. Treatment noncompliance as a function of therapist attributes and social support. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1984;29:212–216. doi: 10.1177/070674378402900305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlund MJ, Wang PS, Berglund PA, Katz SJ, Lin E, Kessler RC. Dropping out of mental health treatment: Patterns and predictors among epidemiological survey respondents in the United States and Ontario. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):845–851. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.5.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Embry LE, Vander Stoep AV, Evens C, Ryan KD, Pollock A. Risk factors for homelessness in adolescents released from psychiatric residential treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39(10):1293–1299. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JF. Substance dependence, abuse, and treatment: Findings from the 2000 national household survey on drug abuse. Rockville MD: SAMHSA, Office of Applied Studies; 2002. (NHSDA Series A-16, DHHS Publication No. SMA 02-3642 ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Fisher WH, Roy-Bujnowski KM, Grudzinskas AJ, Jr, Clayfield JC, Banks SM, Wolff N. Patterns and prevalence of arrest in a statewide cohort of mental health care consumers. Psychiatric Services. 2006;57(11):1623–1628. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.11.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government Accountability Office. Young adults with serious mental illness. Some states and federal agencies are taking steps to address their transition challenge. 2008. GAO-08-678. [Google Scholar]

- Grimes WR, Murdock NL. Social influence revisited: Effects of counselor influence on outcome. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1989;26(4):469. [Google Scholar]

- Grote NK, Swartz HA, Geibel SL, Zuckoff A, Houck PR, Frank E. A randomized controlled trial of culturally relevant, brief interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60(3):313. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.3.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber MG, Karpur A, Deschênes N, Clark HB. Predicting improvement of transitioning young people in the partnerships for youth transition initiative: Findings from a multisite demonstration. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research. 2008;35:488–513. doi: 10.1007/s11414-008-9126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen NB, Lambert MJ, Forman EM. The psychotherapy dose–response effect and its implications for treatment delivery services. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9(3):329–343. [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JJ. Client factors related to premature termination of psychotherapy. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 1985;22:83–85. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson H, Eklund M. Helping alliance and early dropout from psychiatric out-patient care: The influence of patient factors. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2006;41(2):140–147. doi: 10.1007/s00127-005-0009-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustun TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2007;20(4):359–364. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HS, Munson MR, McKay MM. Engagement in mental health treatment among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2012;29(3):241–266. doi: 10.1007/s10560-022-00893-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokotovic AM, Tracey TJ. Premature termination at a university counseling center. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1987;34(1):80. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert M. What we have learned from a decade of research aimed at improving psychotherapy outcome in routine care. Psychotherapy Research. 2007;17(1):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert MJ, Harmon C, Slade K, Whipple JL, Hawkins EJ. Providing feedback to psychotherapists on their patients’ progress: Clinical results and practice suggestions. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;61(2):165–174. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V, Filippucci L, Baiocco R. Therapeutic alliance evaluation in personality disorders psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, Special Issue: The Therapeutic Relationship. 2005;15(1–2):45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Lodi-Smith J, Roberts BW. Getting to know me: Social role experiences and age differences in self-concept clarity during adulthood. Journal of Personality. 2010;78:1383–1410. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00655.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Carroll KM, O’Malley SS, Rounsaville BJ. Motivational interviewing with psychiatrically ill substance abusing patients. American Journal on Addictions. 2000;9(1):88–91. doi: 10.1080/10550490050172263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe R, Rowa K, Antony M, Young L, Swinson R. Using motivational enhancement to augment treatment outcome following exposure and response prevention for obsessive compulsive disorder: Preliminary findings. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies.2008. [Google Scholar]

- McNeill BW, May RJ, Lee VE. Perceptions of counselor source characteristics by premature and successful terminators. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1987;34(1):86. [Google Scholar]

- Meier PS, Donmall MC, McElduff P, Barrowclough C, Heller RF. The role of the early therapeutic alliance in predicting drug treatment dropout. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;83(1):57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rose GS. Toward a theory of motivational interviewing. American Psychologist. 2009;64(6):527–537. doi: 10.1037/a0016830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Hendrickson SM, Miller WR. Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy RT. Enhancing combat veterans’ motivation to change posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and other problem behaviors. In: Arkowitz H, Westra HA, Miller WR, Rollnick S, editors. Motivational interviewing in the treatment of psychological problems: Applications of motivational interviewing. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 57–84. [Google Scholar]

- Newman L. The post-high-school outcomes of youth with disabilities up to 4 years after high school: A report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ogrodniczuk JS, Joyce AS, Piper WE. Strategies for reducing patient-initiated premature termination of psychotherapy. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2005;13(2):57–70. doi: 10.1080/10673220590956429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldham M, Kellett S, Miles E, Sheeran P. Interventions to increase attendance at psychotherapy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(5):928. doi: 10.1037/a0029630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, Pincus HA. National trends in the use of outpatient psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1914–1920. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekarik G. Posttreatment adjustment of clients who drop out early vs. late in treatment. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1992;48(3):379–387. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199205)48:3<379::aid-jclp2270480317>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pekarik G, Wierzbicki M. The relationship between clients’ expected and actual treatment duration. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1986;23(4):532. [Google Scholar]

- Planty M, Hussar W, Snyder T, Provasnik S, Kena G, Dinkes R, … Kemp J. The condition of education 2008 (NCES 2008–031) Washington, DC: NCES, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pulford J, Adams P, Sheridan J. Therapist attitudes and beliefs relevant to client dropout revisited. Community Mental Health Journal. 2008;44(3):181–186. doi: 10.1007/s10597-007-9116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampl S, Kadden R. Motivational enhancement therapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescent cannabis users: 5 sessions, cannabis youth treatment (CYT) series. Vol. 1. Rockville MD: Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, SAMHSA; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Henggeler SW, Brondino MJ, Rowland MD. Multisystemic therapy: Monitoring treatment fidelity. Family Process. 2000;39(1):83–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2000.39109.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheidow AJ. Intervening on substance use in MST for emerging adults: Motivational enhancement therapy (MET) manual. 2009. Unpublished manual. [Google Scholar]

- Sheidow AJ, McCart M, Zajac K, Davis M. Prevalence and impact of substance use among emerging adults with serious mental health conditions. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2012;35(3):235–243. doi: 10.2975/35.3.2012.235.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sims H, Sanghara H, Hayes D, Wandiembe S, Finch M, Jakobsen H, … Kravariti E. Text message reminders of appointments: A pilot intervention at four community mental health clinics in London. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(2):161–168. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderlund LL, Madson MB, Rubak S, Nilsen P. A systematic review of motivational interviewing training for general health care practitioners. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;84(1):16–26. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein L, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Monti PM, Golembeske C, Lebeau-Craven R, Miranda R. Enhancing substance abuse treatment engagement in incarcerated adolescents. Psychological Services. 2006;3(1):25. doi: 10.1037/1541-1559.3.1.0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg ML, Ziedonis DM, Krejci JA, Brandon TH. Motivational interviewing with personalized feedback: A brief intervention for motivating smokers with schizophrenia to seek treatment for tobacco dependence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(4):723–728. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uggen C, Wakefield S. Young adults reentering the community from the criminal justice system: The challenge. In: Osgood W, Foster M, Flanagan C, editors. On your own without a net: The transition to adulthood for vulnerable populations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Valanis B, Whitlock EE, Mullooly J, Vogt T, Smith S, Chen C, Glasgow RE. Screening rarely screened women: Time-to-service and 24-month outcomes of tailored interventions. Preventive Medicine. 2003;37(5):442–450. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Voorhees BW, Fogel J, Reinecke MA, Gladstone T, Stuart S, Gollan J, … Ross R. Randomized clinical trial of an internet-based depression prevention program for adolescents (project CATCH-IT) in primary care: 12-week outcomes. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2009;30(1):23–37. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181966c2a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vander Stoep A, Beresford SA, Weiss NS, McKnight B, Cauce AM, Cohen P. Community-based study of the transition to adulthood for adolescents with psychiatric disorder. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;152(4):352–362. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.4.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra HA, Aviram A, Doell FK. Extending motivational interviewing to the treatment of major mental health problems: Current directions and evidence. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;56(11):643–650. doi: 10.1177/070674371105601102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westra HA, Dozois DJA. Preparing clients for cognitive behavioral therapy: A randomized pilot study of motivational interviewing for anxiety. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2006;30(4):481–498. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckoff A, Swartz HA, Grote NK. Motivational interviewing as a prelude to psychotherapy of depression. In: Arkowitz H, Westra HA, Miller WR, Rollnick S, editors. Motivational interviewing in the treatment of psychological problems: Applications of motivational interviewing. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. pp. 109–144. [Google Scholar]