Abstract

Aims

We compared the role of central blood pressure (BP), ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM), home-measured BP (HMBP) and office BP measurement as risk markers for the development of mild cognitive impairment (MCI).

Methods

70 hypertensive patients on combination medical therapy were studied. Their mean age was 64.97 ± 8.88 years. Eighteen (25.71%) were males and 52 (74.28%) females. All of the patients underwent full physical examination, laboratory screening, echocardiography, and office, ambulatory, home and central BP measurement. The neuropsychological tests used were: Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). SPSS 19 was used for the statistical analysis with a level of significance of 0.05.

Results

The mean central pulse pressure values of patients with MCI were significantly (p = 0.016) higher than those of the patients without MCI. There was a weak negative correlation between central pulse pressure and the results from the MoCA and MMSE (r = −0.283, p = 0.017 and r = −0.241, p = 0.044, respectively). There was a correlation between ABPM and MCI as well as between HMBP and MCI.

Conclusions

The correlation of central BP with target organ damage (MCI) is as good as for the other types of measurements of BP (home and ambulatory). Office BP seems to be the poorest marker for the assessment of target organ damage.

Keywords: Hypertension, Central blood pressure, Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, Home-measured blood pressure, Mild cognitive impairment

Introduction

There are a variety of means of measurement of blood pressure (BP). The results and the threshold values are quite different [1]. The diagnosis and treatment of arterial hypertension is guided primarily by the well-known office, home and ambulatory BP measurements. However, the rate of control and consequently of target organ damage is relatively low in comparison to the variability of drugs available. On the other hand, it is still unclear what the precise role of central BP is in the treatment of arterial hypertension and in the prophylaxis of target organ damage [2, 3].

It is believed that central BP is the most precise type of BP measurement [4, 5, 6]. This leads to the hypothesis that central BP may have a better correlation with target organ damage. As so far as the variable drugs have a different impact on central BP [7, 8], this implies that they may have a differential impact on the prophylaxis of target organ damage. To this moment, there is only scarce information on the role of central BP for the brain hemodynamics in everyday practice.

Another factor is arterial aging. It is best assessed with the markers of elevated arterial stiffness such as elevated pulse wave velocity and central BP [9]. Arterial stiffness may be elevated above the threshold values for the given age in patients with an accumulation of cardiovascular risk factors [10, 11, 12, 13, 14].

Our previous results have confirmed the role of elevated pulse pressure for the development of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) [15]. Which of the available methods for BP measurement is the best with regard to target organ damage and especially brain damage as manifested by MCI is still unclear. In the present study, central BP was included. It is the most precise method for BP measurement. It is considered the pressure that actually affects target organs and thus it has the best predictive value for target organ damage. Its correlation with cognitive impairment is not fully studied. We consider it an important issue to compare its value as a risk factor for cognitive impairment to other hypertension variables that are risk factors for cognitive impairment.

The objective of this study was to compare the role of central BP, ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM), home-measured BP (HMBP) and office BP measurements as risk markers for the development of MCI.

Methods

This is an observational study with a minimal follow-up period of 6 months as required for cognitive impairment reassessment. Seventy hypertensive patients were included in the study only after signing a written consent for the participation in a scientific study (according to the Helsinki declaration for human research). The study was approved by the Medical Science Commission of Sofia Medical University, Bulgaria and its Ethics Committee with the contract numbers 18/2011 and 53/2011. All of the patients attended the cardiology clinic of a University Hospital.

Inclusion Criteria

The following inclusion criteria were considered: arterial hypertension with a history of at least 1 year; left ventricular ejection fraction above 35%; antihypertensive treatment; and regular self-measurement of brachial BP.

Exclusion Criteria

The following exclusion criteria were considered: acute coronary syndrome with or without ST elevation and indications for urgent coronary intervention; acute stroke; acute or chronic heart failure with ejection fraction less than 35%; acute kidney dysfunction or end-stage chronic kidney disease and chronic dialysis; coma, sopor or somnolence; taking antidepressants during the last 2 weeks; with impaired speech, vision, hearing; heavy head trauma; epilepsy; anemic syndrome; atrial fibrillation with suboptimal anticoagulation, verified with INR testing on enrollment; poorly controlled diabetes mellitus; hypo- or hyperglycemic coma; asthenic dynamic syndrome; alcoholism; diagnosed psychiatric disease; and diagnosed Alzheimer or other types of dementia.

Anamnesis and a comprehensive hypertensive history were gathered for every patient. All of them completed physical examination and basic laboratory testing.

Methods for BP Measurement

Home-Measured BP. Values were gathered after education of the patients how to measure their BP values properly and to keep a diary for 3–7 days [16, 17]. Target values were chosen in accordance with scientific recommendations [1].

24-h Ambulatory BP Monitoring. ABPM was conducted with TM2430 (Boso), validated according to the requirements of the European Society of Hypertension and the British Hypertension Society. It is an oscillometric sphygmomanometer. The measurement protocol was accepted as suitable if it consisted of at least 70% valid measurements, is distributed proportionally during the day and night and conducted with patients without limitations of their habitual daily activities, keeping their regular medication regimen and duration of the recording (24 h). The cuff was put on the nondominant hand and every patient received instructions how to behave so that the apparatus could make valid measurements. Measurement intervals were set at 15 min during the day and at 30 min during the night, with passive day and night period registration (7.00 a.m. to 10.00 p.m.). Dipping index and BP variability were automatically acquired.

Central Aortic BP. The central aortic BP was measured with Sphygmocor CvMS 9 (AtCor Medical) [18]. The same requirements as during standard BP measurement were followed, namely: resting for 10 min and refraining from smoking, eating and physical activity for 2 h. After brachial BP measurement, we applied an applanation tonometer at the radial artery. At least three valid measurements with an operator index above 90% were taken. The collected variables were: heart rate, ejection duration, peripheral systolic and diastolic BP, aortic systolic and diastolic BP, mean pressure (peripheral and aortic), pulse pressure (peripheral and aortic), time to 1st and 2nd peak and time to reflection, augmented pressure, pressure at 1st and at 2nd peak, augmentation index, subendocardial viability ratio (Buckberg index), mean pressure in systole and in diastole, and end-systolic pressure.

Neuropsychological Tests Used

Neuropsychological tests were conducted in private, at least 1 h apart and after explanation of their characteristics.

Mini Mental Sate Examination [19]. This is the conventional neuropsychological test that is used in almost every study for dementia. It is a validated and proven method for the diagnosis of the advanced stages of cognitive impairment, but quite insensitive to the earliest phases. The cognitive domains tested with the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) are: orientation, registration, attention and calculation (serial 7-s or spelling backwards), recall, language and praxis (naming, repetition, 3-stage command, reading, writing, coping). The threshold for cognitive impairment is 24 points from a total of 30. The time given for completion of the test is 5–10 min.

Montreal Cognitive Assessment [20]. The low sensitivity of MMSE led us to the inclusion of another test which is more sensitive and specific for the earliest stages of cognitive impairment. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a 10-min compilation of neuropsychological tests aimed at evaluating frontal executive functioning and attention. The threshold for diagnosing cognitive impairment is 26 (out of a total of 30 points). Cognitive domains tested via MoCA are: attention, concentration, executive functioning, language, memory, visual-constructional skills, abstraction, delayed recall, and orientation.

Geriatric Depression Scale [21]. Depression often coexists with dementia, but its correlation with MCI is not defined. The test was used to study dementia patients and to explain whether it was correlated with earlier stages of cognitive impairment.

4-Point Version of the Scale for Evaluating the Performance in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living [22]. Impaired daily functioning is the art of dementia diagnosis. The test was used to better define patients with advanced cognitive impairment.

Statistical Methods

SPSS 19 was used for the statistical analysis. Descriptive analysis, t test, and correlation analysis are performed depending on the particular question. A certified statistician from the National Statistical Institute of Bulgaria did the statistical analysis. The precise method which was chosen depended on whether means were compared or whether we studied the correlation. The standard for the medical statistics, i.e., the 95% confidence interval, was used.

Results

This was a prospective study of 70 hypertensive patients: 18 (25.71%) were males and 52 (74.28%) females. The minimal follow-up period was 6 months as required for the proper reevaluation of cognitive impairment. The mean age was 64.97 ± 8.88 years. The mean hypertension history was 9.53 ± 6.63 years. The mean test results were as follows: 24.78 ± 3.57 points for the MoCA and 28.38 ± 1.55 points for the MMSE. Thirty-six (51.43%) of the patients had MCI as assessed with the more sensitive MoCA test. Their mean MoCA score was 22.14 ± 2.96 points and their mean MMSE score was 27.67 ± 1.51 points. None of the patients were impaired in their abilities of everyday activities. Two (2.86%) had depression, but no other signs of dementia. The mean results from the central BP measurement are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean results from the central blood pressure measurement

| Variable | The whole studied population | With MCI | Without MCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 110.17±21.15 | 112.94±24.31 | 107.23±17.07 |

| Central diastolic pressure, mm Hg | 72.13±8.11 | 72.32±8.71 | 72.32±8.71 |

| Central pulse pressure, mm Hg | 39.21±14.63 | 43.27±15.42 | 34.91±12.59 |

| Augmentation pressure, mm Hg | 12.45±5.01 | 13.17±8.20 | 12.78±4.99 |

| Augmentation index, % | 25.55±11.04 | 23.92±12.69 | 26.22±7.59 |

| Ejection duration, ms | 287.6±27.10 | 292.97±7.86 | 281.91±25.44 |

| Buckberg index, % | 179.51±36.28 | 176.39±33.58 | 182.82±39.17 |

| Mean pressure in systole, mm Hg | 99.47±13.79 | 102.42±13.16 | 96.56±14.20 |

| End-systolic pressure, mm Hg | 103.28±15.30 | 106.11±14.3 | 100.29±15.97 |

| Pressure time index systole | 1,921.03±401.86 | 1,946.61±334.53 | 1,893.94±466.36 |

| Pressure time index diastole | 3,367.31±475.90 | 3,415.78±421.92 | 3,316±528.66 |

MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

The mean values for the HMBP of the studied group of patients were as follows: 139.14 ± 17.63 mm Hg for the systolic BP, 83.28 ± 11.09 mm Hg for the diastolic BP, and 55.28 ± 13.07 mm Hg for the pulse pressure. The mean office BP values were: 141.78 ± 19.38 mm Hg for the systolic BP, 84.71 ± 12.30 mm Hg for the diastolic BP, and 57.07 ± 11.91 mm Hg for the pulse pressure. The mean values for the ABPM are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Mean values for the ABPM

| Period | Pressure | For all studied, mm Hg | With MCI, mm Hg | Without MCI, mm Hg | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-h ABPM | systolic | 132.10±16.95 | 137.97±17.80 | 126.87±14.59 | 0.018 |

| diastolic | 76.30±8.75 | 77.95±7.57 | 74.84±9.59 | 0.20 | |

| pulse | 55.79±11.32 | 60.02±12.40 | 52.04±8.90 | 0.01 | |

| Day ABPM | systolic | 133.75±17.98 | 137.98±21.00 | 129.97±14.10 | 0.029 |

| diastolic | 77.95±8.98 | 78.94±8.31 | 77.08±9.60 | 0.419 | |

| pulse | 56.78±11.15 | 61.14±12.04 | 52.88±8.80 | 0.006 | |

| Night ABPM | systolic | 123.29±19.3 | 129.29±20.05 | 117.93±17.23 | 0.031 |

| diastolic | 70.07±7.52 | 73.05±8.69 | 67.42±10.44 | 0.039 | |

| pulse | 53.59±12.13 | 57.03±13.56 | 50.51±9.97 | 0.050 | |

ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; MCI, mild cognitive impairment.

The group of patients without MCI had significantly lower values for most variables of ABPM (24-h systolic and pulse pressure, day systolic and pulse pressure, night systolic, diastolic and pulse pressure) than the corresponding patients with MCI.

Twenty-two (31.43%) of the studied group had only one cardiovascular risk factor: arterial hypertension. Twenty (28.57%) were smokers, 34 (48.57%) had dyslipidemia, 10 (14.28%) had diabetes mellitus, and 15 (21.43%) were obese. The total cardiovascular risk was assessed with SCORE system. 3.17% had low risk; 38.09% had intermediate; 20.63% had high; and 38.09 had a very high cardiovascular risk.

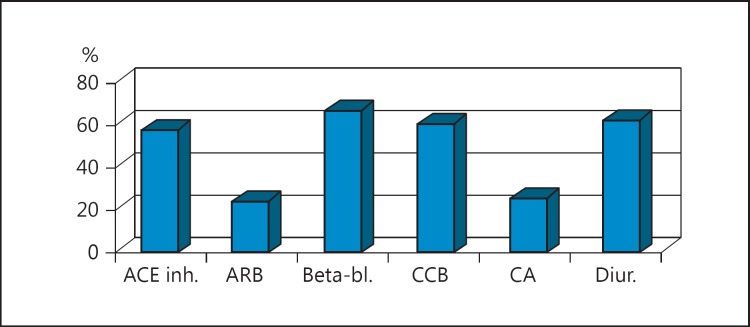

As far as target organ damage was concerned, 34 (48.57%) of the patients had concentric left ventricular hypertrophy. All of the patients were taking combination antihypertensive treatment (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Percent of patients who take a certain group of medication. ACE inh., angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; ARB, angiotensin receptor blockers; Beta-bl., β-blockers; CCB, calcium channel blockers; Diur., diuretics.

There was no significant difference in the mean neuropsychological results between males and females in this specific group of patients. We did not find any difference in MoCA and MMSE mean results that can be explained by specific groups of medications used.

Central BP and MCI

We used the t test to find if there was any significant difference in the mean central BP between the groups with and without MCI. We only found a significant difference in the values of the central pulse pressure. The group of patients with MCI had a mean central pulse pressure of 43.28 ± 15.42 mm Hg. The group of patients without MCI had a mean central pulse pressure of 34.91 ± 12.59 mm Hg. The level of significance was p = 0.016.

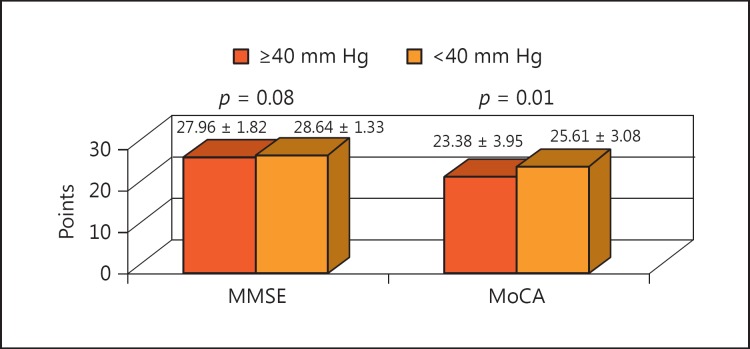

There were a few trials that were aimed at finding the precise normal value thresholds for the central BP parameters. The threshold that was used for central pulse pressure was 40 mm Hg. Patients with a central pulse pressure above 40 mm Hg had significantly lower results in the neuropsychological tests, both in the MoCA and MMSE, than the patients with a central pulse pressure below 40 mm Hg (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the mean neuropsychological test results between patients with central pulse pressure below and above 40 mm Hg. MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment.

The correlation analysis confirmed that central pulse pressure is a marker for MCI. We found a weak negative correlation between central pulse pressure and the results from the neuropsychological tests. For MoCA: r = −0.283 and p = 0.017; for MMSE: r = −0.241 and p = 0.044. The higher the central pulse pressure the lower the results from the tests and, consequently, the more advanced the cognitive impairment assessed both with the more sensitive test (MoCA) and the more specific test (MMSE). In this specific population of hypertensive patients with added cardiovascular risk, there was a tendency (p = 0.099) for central systolic BP above 120 mm Hg to be correlated with lower results in the neuropsychological tests (23.63 ± 2.89 vs. 25.21 ± 3.73 for MoCA).

The correlation analysis also showed a significant correlation between the ABPM measurements and the results from the neuropsychological tests. The results were significant for the 24-h, day and night systolic and pulse pressure. The correlation found was intermediate in strength and negative – the higher the ABPM systolic and pulse pressure during the 24-h period, day or night, the lower the results from the MoCA and MMSE. The corresponding level of significance and correlation coefficients are given in Table 3. The correlation analysis did not reach statistical significance when exploring the association between ABPM diastolic BP and the neuropsychological tests in this specific group of patients.

Table 3.

Correlation between ABPM ant the results from MoCA and MMSE with the corresponding correlation coefficients and level of significance

| ABPM variable | MoCA | p | MMSE | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24-h SBP | –0.323 | 0.021 | −0.368 | 0.008 |

| 24-h PP | −10.356 | 0.01 | −0.454 | 0.001 |

| Day SBP | −0.520 | 0.023 | −0.490 | 0.033 |

| Day PP | −0.374 | 0.006 | −0.437 | 0.001 |

| Night SBP | −0.281 | 0.042 | −0.410 | 0.002 |

| Night PP | −0.257 | 0.063 | −0.435 | 0.001 |

ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; SBP, systolic blood pressure; PP, pulse pressure.

HMBP and MCI

The correlation between HMBP and the results from the neuropsychological tests was low in strength: r = −0.239 (p = 0.046) for MoCA and −0.271 (p = 0.023) for MMSE for the systolic BP. The results for the home-measured pulse pressure reached statistical significance only for MMSE (r = −0.248, p = 0.038).

Office BP and MCI

We did not find any significant correlation between office measurement of BP and neuropsychological results.

Discussion

As central BP is studied more and more as a better predictor for cardiovascular risk than the brachial BP, it was interesting to see if there is a correlation between this and one of the clinical manifestations of target organ damage – mainly MCI. We used a combination of two neuropsychological tests: one more sensitive – MoCA, that accounts for education and checks a variety of cognitive functions, and one more specific – MMSE. In our pilot study, we demonstrated that central elevated central systolic and pulse pressure were correlated with MCI. The higher the values of the central BP, the lower the results from the neuropsychological tests. The correlation between the ABPM and MCI was in the same direction, but stronger. That might be explained by the fact that we had 24-h brachial monitoring, but the central BP measurement was a mean of several measurements at a single visit. We used Sphygmocore as a gold standard, but its protocol is not for 24 h [23].

The correlation between office BP and MCI did not reach statistical significance. That can be explained by the fact that although conducted several times, office BP is again an incidental measurement. This underlines the importance of continuous BP monitoring, which can help in the assessment of the variability and the circadian rhythm. Our group conducted a larger study with 931 patients that proved a correlation between office BP and MCI. In this larger group of patients, we did not find any significant difference in MCI between males and females. That is why our current study was conducted without adjustment for sex. There were no extremes in the BMI and no adjustment was necessary either. Maybe in a larger group of patients, the results will reach statistical significance for the central BP as well.

Reverse causation is a possible explanation that could be discussed. It is possible that individuals with MCI forget to take their medication on a regular basis, thus resulting in higher or less stable BP.

Potentially confounding factors may be age, sex, education, BMI, and treatment. The educational status was incorporated in the MoCA and thus eliminated as a factor. Also many studies with MMSE are conducted without using different thresholds for patients with different education. The potential lack of difference in the neuropsychological test results can be explained by the fact that the group is relatively small and for such a clear definition between sexes a large population-based study is needed.

For the damage of the target organs, it is difficult to set certain thresholds. This is even more difficult in patients with multiple cardiovascular risk factors, in whom an accumulation of adverse effects is expected. It is probably better to talk about a continuum of correlation than about thresholds. This is still not defined in the scientific literature. The threshold of 40 mm Hg for the central pulse pressure was chosen as a recommendation for central BP measurements on the basis of what is currently known and on the basis of the available trials for a validation of the apparatuses in the general population. There is a lot of work in the field before we can clearly state thresholds. Still, as with office and with ABPM, this is an “orientation point.”

Central systolic and pulse pressure, although indirect, are still markers of arterial stiffness [24]. The correlation between central systolic and pulse pressure and MCI can be explained by the fact that a flow with higher pulsatility than normal reaches the microcirculation [25]. If long-standing, this process may exhaust the compensatory mechanisms of the microcirculation and compromise its functioning. One of the clinical manifestations of this is MCI.

Our results are in concert with the works of Dias et al. [26]. They found a significant correlation between central aortic systolic pressure and intima-media thickness, and between cognitive impairment and central aortic systolic pressure. The neuropsychological test they used was the MMSE and the two compared groups were on the two sides of the MMSE threshold value.

One potential explanation for the lack of a significant correlation between neuropsychological test results and specific antihypertensive medications is that besides their BP-lowering effects, the various medications have different penetration through the blood-brain barrier. This may potentially lead to differential effects of cognitive functioning. Another explanation is the fact that all of the patients were on combination therapy and it is difficult to define any specific medication effect on cognitive functioning.

Central BP is an important risk marker for MCI. It can be easily assessed in the everyday practice and used as a screening tool for suboptimal control and target organ damage (MCI). There is a correlation between brachial pulse pressure and MCI. Central aortic pressure may be a better predictor for target organ damage and may define more precisely the risk for cognitive impairment than the home-measured and office brachial pressure. Central pulse pressure is correlated with cognitive impairment in hypertensive patients: the higher the central pulse pressure, the more impaired cognitive functioning. Central pulse pressure may become a new treatment target in hypertensive patients with clinically manifested target organ damage.

However, the limitation of the study is that the study population consists of only 70 patients. The future directions are as follows: to enlarge the study population and to define specific central aortic pressure values that raise the risk for cognitive impairment in the everyday patient (with concomitant cardiovascular risk factors) and to define the specific influence of every central BP parameter on cognitive functioning.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the Sofia Medical University, Bulgaria.

References

- 1.Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, Germano G, et al. 2007 guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1462–1536. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agabiti-Rosei E, Mancia G, O'Rourke M, Roman M, Safar M, Smulyan H, Wang J, Wilkinson I, Williams B, Vlachopoulos C. Central blood pressure measurements and antihypertensive therapy: a consensus document. Hypertension. 2007;50:154–160. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.090068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.London G, Asmar R, O'Rourke M, Safar M. Mechanism(s) of selective systolic blood pressure reduction after a low-dose combination of perindopril/indapamide in hypertensive subjects: comparison with atenolol. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L, Boutouyrie P, Giannattasio C, Hayoz D, Pannier B, Vlachopoulos C, Wilkinson I, Struijker-Boudier H. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2588–2605. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roman M, Devereux R, Kizer J, Lee E, Galloway J, Ali T, Umans J, Howard B. Central pressure more strongly relates to vascular disease and outcome than does brachial pressure: the Strong Heart Study. Hypertension. 2007;50:197–203. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.089078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roman M, Devereux R, Kizer J, Okin P, Lee E, Wang W, Umas J, Calhoun D, Howard B. High central pulse pressure is independently associated with adverse cardiovascular outcome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1730–1734. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams B, Lacy P, Thom S, Cruickshank K, Stanton A, Collier D, Hughes AD, Thurston H, O'Rourke M. Differential impact of blood pressure-lowering drugs on central aortic pressure and clinical outcomes. Circulation. 2006;113:1213–1225. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.595496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams B, Lacy P. Central aortic pressure and clinical outcomes. J Hypertens. 2009;27:1123–1125. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832b6566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McEniery C, Hall I, Qasem A, Wilkinson IB, Cockcroft JR, ACCT Investigators Normal vascular aging: differential effects on wave reflection and aortic pulse wave velocity: the Anglo-Cardiff Collaborative Trial (ACCT). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1753–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safar M, Blacher J, Pannier B, Guerin AP, Marchais SJ, Guyonvarc'h PM, London GM. Central pulse pressure and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension. 2002;39:735–738. doi: 10.1161/hy0202.098325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Safar M, Jankowski P. Central blood pressure and hypertension: role in cardiovascular risk assessment. Clin Sci. 2009;116:273–282. doi: 10.1042/CS20080072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Safar M, Leevy B, Struijker-Boudier H. Current perspectives on arterial stiffness and pulse pressure in hypertension and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2003;107:2864–2869. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000069826.36125.B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steppan J, Barodka V, Berkowitz D, Nyhan D. Vascular stiffness and increased pulse pressure in the aging cardiovascular system. Cardiol Res Pract. 2011;2011:263585. doi: 10.4061/2011/263585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mattace-Raso F, van der Cammen T, Hofman A, van Popele NM, Bos ML, Schalekamp MA, Asmar R, Reneman RS, Hoeks AP, Breteler MM, Witteman JC. Arterial stiffness and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke. The Rotterdam Study. Circulation. 20016;1113:657–663. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.555235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yaneva-Sirakova T, Tarnovska-Kadreva R, Traykov L. Pulse pressure and mild cognitive impairment. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2012;13:735–740. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e328357ba78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Brien E, Asmar R, Beilin L, Imai Y, Mancia G, Mengden T, Myers M, Padfield P, Palatini P, Parati G, Pickering T, Redon J, Staessen J, Stergiou G, Verdecchia P, on behalf of the European Society of Hypertension Working Group on Blood Pressure Monitoring Practice guidelines of the European Society of Hypertension for clinic, ambulatory and self blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens. 2005;23:697–701. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000163132.84890.c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perk J, de Backer G, Gohlke H, Graham I, Reiner Z, Verschuren M, Albus C, Benlian P, Boysen G, Cifkova R, Deaton C, Ebrahim S, Fisher M, Germano G, Hobbs R, Hoes A, Karadeniz S, Mezzani A, Prescott E, Ryden L, Scherer M, Syvänne M, Scholte op Reimer WJ, Vrints C, Wood D, Zamorano JL, Zannad F. European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1635–1701. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.www.atcormedical.com/pdf/SphygmoCor%20Clinical%20Guide.pdf (accessed May 10, 2009).

- 19.www.heartinstitutehd.com/Misc/Forms/MMSE.1276128605.pdf (accessed April 12, 2009).

- 20.www.mocatest.org/default.asp (accessed May 12, 2009).

- 21.Burke W, Houston M, Boust S, Roccaforte W. Use of the Geriatric Depression Scale in dementia of the Alzheimer type. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1989;37:856–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb02266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barberger-Gateau P, Dartigues J, Lerenneur L. Four instrumental activities of daily living score as a predictor of one-year incident dementia. Age Aging. 1993;22:457–463. doi: 10.1093/ageing/22.6.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkinson I, McEniery C, Cockcroft J. Central blood pressure estimation for the masses moves a step closer. J Hum Hypertens. 2010;24:495–497. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2010.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sharman J, Stowasser M, Fassett R, Merwick H, Franklin S. Central blood pressure measurement may improve risk stratification. J Hum Hypertension. 2008;22:838–844. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hachnski V, lliff L, Zihka E, Du Boulay G, McAllister V, Marshall J, Russel R, Symon L. Cerebral blood flow in dementia. Arch Neurol. 1975;32:632–637. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1975.00490510088009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dias E, Giollo L, Martinelli D, Mazeti C, Junior H, Viela-Martin J, Jugar-Toledo J. Carotid intima-media thickness is associated with cognitive deficiency in hypertensive patients with elevated central systolic blood pressure. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2012;10:41. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-10-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]