Abstract

Cancer care in elderly patients is complex. A recent survey showed that among mostly academic surgeons, practice patterns varied in the care of elderly patients. The authors suggested three areas of intervention in improving care of this population: frailty assessment, nutritional assessment, and assessment of quality of life.

Keywords: Elderly, Attitudes, Cancer, Surgery

Rationale for Performing a Survey on Surgeons' Attitudes towards the Management of Elderly Patients with Cancer

Cancer is a disease of the elderly. In spite of this well-known piece of data, and together with the epidemiological evidence that the age of the world population is dramatically growing, very little level 1 evidence on treating cancer in this (large) group of people is available. In most of the cases, cancer treatment does not come from large randomized controlled trials, and this is because patients older than 70 years are often excluded from prospective studies [1].

In addition, information obtained from the methodologically well-designed studies does not always apply to elderly patients, who experience different benefits, side effects, and life expectancy than younger cohorts [2]. Unfortunately, this may also translate in substandard cancer care delivered to this group. EUROCARE-5 [3], the widest collaborative research project on cancer survival in Europe, including 21 million cancer diagnoses provided by 116 Cancer Registries in 30 European countries, has recently flagged an unfavorable cancer-related survival rate among the oldest patients. The same scenario has been reported by the National Cancer Intelligence Network, which shows that elderly patients in the UK affected by solid tumors receive less surgery as compared to their younger counterparts [4]. The difficulty in applying the ‘standard of care’ more broadly needs to be searched for in a combination of patients' comorbidities, psychosocial issues, and physicians' attitudes.

The aim of an intersociety, multicultural survey is to eventually offer the surgeon a perspective of patients' treatment worldwide, and for the societies' leadership to highlight attitudes deviating from the available recommendations and areas amenable for clinical improvement.

Survey Results

The Surgical Task Force of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) performed a survey of surgical oncologists in Europe and the USA to determine their treatment approach for elderly cancer patients. The possible survey participants were all of the members of the European Society of Surgical Oncology (ESSO) and the Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO) who were asked 20 multiple-choice questions about their practice model and treatment approach for elderly patients. 11% of possible participants responded (251/2,281 surgeons). Of those that responded, 62% had a focus of their practice on breast surgery, 43% on colorectal surgery, and 27% on hepatobiliary surgery. Almost half (44.6%) of the respondents were practicing at academic centers.

There was disagreement among respondents even in the definition of the term ‘elderly’, with 32% defining it as age 75 or older, 30% as age 70 or older, and 25% as age 80 or older. However, agreement was reached (>90%) in the intention to offer surgery to elderly patients regardless of their age. Fewer surgeons (48%) considered preoperative frailty assessment mandatory. Furthermore, only 6.4% of respondents had adopted the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in their practices. In contrast, surgeons are more likely to assess nutrition preoperatively (38.2%), with 56% planning to optimize nutritional status preoperatively. In line with this, 70% of surgeons believed it was beneficial to proceed with up to 4 weeks of prehabilitation, with nutrition as well as physical and physiological support preoperatively.

If patients were found to have severely limited cognitive function, but with maintained functional capacity, half of the surgeons would still not offer surgery. 35% would offer surgery regardless of the cognitive status, and 14% would consult the family and caretakers before making the decision. In keeping with this low percentage reporting of collaboration with caretakers, less than half of the respondents (36.3%) reported routine collaboration with geriatricians.

Surgical oncologists with a specialty in visceral surgery (colorectal, hepatobiliary, etc.) were more likely to define elderly at a lower age, to use a specific age at which to stop offering elective cancer surgery, to employ frailty and nutritional assessment preoperatively, and to treat nutritional deficiencies preoperatively than their colleagues in breast or reconstructive surgery. In addition, visceral surgeons were more likely to collaborate with a geriatrician. The main endpoints suggested by all of the respondents for further study on elderly patients were quality of life (QoL) and functional recovery [5].

Despite the fact that the survey only had an 11% response rate, we can deduce that all surgeons are not yet adopting the role for preoperative functional and nutritional assessment, prehabilitation, or collaboration with medical colleagues and patient caregivers. The three main areas for improvement identified by the authors were frailty assessment, nutritional assessment, and assessment of QoL. These metrics will be addressed in the remainder of this article.

Frailty Assessment

Several systems to evaluate patients, stratify operative risk, and highlight possible areas of intervention for prehabilitation have been proposed and validated. Regardless of the system of choice, it is essential to systematically assess elderly cancer patients in order to determine if the patient is fit for surgery, which surgical plan is most appropriate, and which parameters can be optimized preoperatively. Therefore, it is mandatory, regardless of the preferred system, to obtain information about three main domains: cognitive status (including history of delirium), independence/living situation, and sarcopenia/gait ability/nutrition [6, 7, 8, 9, 10].

In addition, the role of the Timed Up and Go test, the handgrip strength test, Nutritional Risk Screening, activities of daily living (ADL), and others have been assessed [6, 7]. Organ-specific diseases and environmental factors make a ‘one-size-fits-all’ risk-predicting tool impossible to find. The lack of a standardized preoperative assessment is, indeed, one of the main reasons why so few meaningful conclusions can be drawn from many papers in the literature. In addition, no homogeneity in the study population can be verified or is objectively reported. This is particularly true for literature on elderly patients where intergroup variability is so highly represented and usually so poorly assessed, often nullifying the value of final conclusions.

The role of a systematic preoperative assessment is not only focused on screening good, fit candidates for surgery but also on identifying situations or conditions that may benefit from a preoperative intervention. After a careful preoperative evaluation, a tailored procedure can be planned with the intent of obtaining the desired result and minimizing stressors.

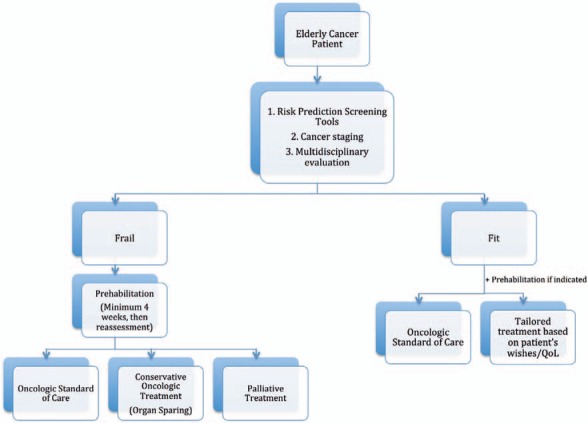

Screening for frailty and any possible areas of intervention is only a part of the preoperative assessment and decision-making process. Equally important is the discussion of every patient in a multidisciplinary group. The multidisciplinary approach is, as always, of great value when treating elderly, challenging patients in order to not overlook any aspect of the patients' complexity. This is particularly valuable within the field of geriatric oncology where a combination of a disease- and patient-oriented approach needs to be pursued. Clinical data have confirmed that this approach can improve measurable outcomes and QoL in the geriatric population undergoing surgery [11]. The ideal multidisciplinary team should include not only cancer-specific professionals (surgical, medical and radiation oncologists) but also geriatricians, anesthesiologists, physical therapists, nutritionists, case managers, and geriatric nurse practitioners. An algorithm for the treatment of elderly cancer patients is proposed in figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Proposed algorithm for the treatment of elderly patients with cancer.

Nutritional Assessment

Nutritional assessment has been increasingly stressed as part of a preoperative optimization strategy for all patients, but has been increasingly important in the elderly. Rates of malnutrition in the elderly have been shown to be 5.8% in the community, 13.8% in nursing homes, 38.7% in hospitals, and 50.5% in rehabilitation centers [12]. Malnutrition is associated with an increased rate of adverse postoperative outcomes including infectious complications, wound complications including anastomotic leak, and increased length of stay for patients undergoing elective surgery of the gastrointestinal tract [13].

Barbosa et al. [14] showed that 36.4% of patients with colorectal cancer (CRC) were malnourished preoperatively. van Stijn et al. [15] performed a systematic review over 10 years to assess the role of evaluation of preoperative nutrition parameters in predicting postoperative outcomes in elderly patients. They showed 15 appropriate articles out of 463 total articles and found great heterogeneity in the parameters to evaluate preoperative nutritional status and postoperative outcomes. They found only two significant preoperative predictors of postoperative outcomes: serum albumin and greater than 10% weight loss in the last 6 months [15]. A nomogram, based on the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Program 10,392 elderly patients' database, recently confirmed that preoperative weight loss is statistically responsible for anastomotic leak after CRC surgery [16].

The best practice guidelines from the American College of Surgeons and the American Geriatrics Society recommend that all patients be evaluated for their nutritional status including measurement of body mass index, prealbumin and albumin, and inquiry about weight loss in the past year. Patients deemed to be malnourished preoperatively should undergo nutritional assessment by a nutritionist, and, if possible, delay of surgery for optimization [17].

Prehabilitation

One cannot discuss assessment of frailty and nutrition without a mention of prehabilitation to follow. Prehabilitation is a modern strategy, gathering all of the initiatives carried out from the time of diagnosis to the time treatment starts in order to improve functional capacity and functional recovery. Prehabilitation before oncologic surgery is a new topic compared with the vast knowledge gained on post-treatment rehabilitation programs and outcomes for both cancer and non-cancer patients [18]. Prehabilitation includes the management and optimization of preoperative conditions, such as diabetes and cardiovascular function and the promotion of smoking cessation. Moreover, the goal of this strategy is not only to focus on muscle strength reinforcement but also on the nutritional and emotional/psychological management of patients undergoing major surgery. Carli et al. [19] have shown that functional capacity was improved by prehabilitation, whether by adherence to a strenuous preoperative activity schedule (bike and muscle-strengthening exercises) or by a 30-min walking and breathing exercise regimen 3 times a week. However, many questions are still ongoing regarding how older adults undergoing surgery may or may not benefit from perioperative regimens [20].

Issues with prehabilitation are poor compliance of patients to the regimen and the need for a prolonged time period from diagnosis to surgery (at least 4–6 weeks) in order to observe tangible improvement in postoperative outcomes. What is clear is that prehabilitation is not a substitute for good surgical and tailored postoperative treatment, especially in the elderly. As a consequence, it should not reduce the morbidity and mortality rate. Prehabilitation improves functional recovery and, perhaps, patient independence and active life expectancy [21]. Li et al. [22] showed how a trimodal prehabilitation program dramatically changed postoperative functional walking capacity, self-reported physical activity, and health-related QoL (HRQoL). This randomized trial was designed for CRC patients awaiting surgical treatment and included 30 min of walking and breathing exercises 3 times a week, a nutritional supplement of up to 1.2 g/kg body weight, and anxiety-reducing techniques. The mean age of the 42 patients enrolled and the 45 patients in the control group was 67.4 ± 11 years; a prehabilitation protocol was carried out for a mean time of 33 days (range 21–46 days). Interestingly, the patients in the intervention group increased the distance covered at the 6-min walking test during prehabilitation, surpassing the preoperative results of the control group. 4 and 8 weeks after surgery, while the physical ability of the control patients declined and did not reach their pretreatment level, prehabilitated patients regained the ability to walk farther than their preoperative baseline. The same trajectory was shown for self-reported physical activity, while anxiety and depression were shown to be lower than the patient baseline 4 weeks postoperatively. Even more interestingly, fewer postoperative complications were recorded in patients who improved their walking ability during prehabilitation while people whose functional capacity declined during the pretreatment time had poorer outcomes. Therefore, response to the prehabilitation regimen may be an additional screening tool for elderly patients undergoing surgery for cancer.

Quality of Life

Older age often comes with decreased independence, and declining health is often a major contributor to decreased functional capacity. Elderly patients often have multiple comorbidities and may have minimal social support; thus, a cancer diagnosis becomes more complicated in this population. The goal of surgical care in the elderly is to obtain a patient-centered, tailored treatment while focusing attention on the patients' QoL rather than simply the 5-year disease-free survival.

Many cancer surgeons recognize the particular challenges of performing surgery in the elderly as compared to the younger population [23]. In particular, the duration of postoperative treatment may be longer than in young patients, complications may be more severe, there may be medicolegal issues of obtaining an informed consent, especially if the patient cannot consent for themselves and has not designated a proxy, and there are ethical questions raised related to end-of-life care [24].

Communication in these cases is essential with the patients, who should be able to make their own decisions and designate their goals of care, if able, but also with their family and caretakers [25]. Patients' perspectives are essential in establishing a proper understanding of the QoL goals. Despite the prevalence of cancer in the elderly population and the increasing impetus for QoL measurement, not many studies have been published focusing on patient experience [26]. Weaver et al. [27] showed that mental and physical health were interrelated in both young and elderly patients with cancer, which both affect their perspective about their diagnosis and expectations.

Banks et al. [28] analyzed self-reported questionnaire-based data from 89,574 Australian men and women with cancer sampled from the Medicare database and concluded that ‘the risk of psychological distress in individuals with cancer relates much more strongly to their level of disability than it does to the cancer diagnosis itself’. Disability and/or lack of independence in the ADL seem be more impactful on the patients' QoL than their diagnosis of cancer.

Some cancer-specific outcomes have been historically associated with a negative impact on patients' self-esteem and QoL. Among the possible outcomes, a stoma has been considered a stressor for patients with CRC. However, this assumption has been challenged more recently. A large meta-analysis on the impact of a stoma-forming procedure (abdominal perineal resection vs. low anterior resection) on 1,443 patients with CRC failed to show a reduction in the QoL in patients with fecal diversion [29]. This was confirmed by Bossema et al. [30] who showed no difference in HRQoL, emotional function, or understanding of the illness among elderly rectal cancer patients with or without a stoma. Therefore, specific outcomes may not affect a patient's QoL as much as once thought and patient-specific treatment should be undertaken.

Patient-centered outcome studies should be implemented in the oncogeriatric field in order to face modern health care system challenges [31]. The risk of postoperative disability needs to be fully discussed with patients and their families with the goal of promoting faster functional recovery and regaining independence. In addition, goals, expectations, and health status should be discussed along with utilization of self-reported QoL tools. QoL and functional outcomes (sexual dysfunction, fecal and urinary incontinence, etc.) evaluations are often seen as too time-consuming to be systematically incorporated into busy clinical practices.

Recently, Fernando et al. [32] described the use of two self-administered QoL questionnaires as part of a prospective, randomized controlled trial comparing sublobar lung resection with sublobar lung resection with locally applied brachytherapy. Regardless of the specific outcomes, the authors were able to demonstrate that self-assessment questionnaires are feasible in both the surgical office and ward. Other studies verified that self-assessment questionnaires have been useful in predicting adverse outcomes after chemotherapy and surgery [33, 34].

QoL and patients' perspectives can no longer be considered secondary outcomes for oncogeriatric patients. Restoration of independence seems to be the highest priority as it directly affects patients' perception of QoL. HRQoL data at diagnosis can identify vulnerable subpopulations in elderly patients preoperatively and can be useful in selecting fit patients preoperatively [35, 36]. Regardless of the evaluation tool chosen, data about QoL should be incorporated in every surgical practice, putting the patient at the center of the care process. With that goal in mind, the GOSAFE (Geriatric Oncology Surgical Assessment and Functional rEcovery after Surgery) study has been recently launched by the ESSO in collaboration with the SIOG (@GOSAFEstudy). The GOSAFE study is a prospective international collaborative high-quality registry aiming to gain knowledge about postoperative outcomes in elderly cancer patients with a particular emphasis on QoL and functional recovery. The objective is to obtain meaningful data to assist clinicians in tailoring care of elderly patients to avoid under-/overtreatment and to provide robust data to identify new strategies for improving functional outcomes in these patients.

Conclusions

It has been demonstrated that elderly patients benefit from tailored, patient-centered, multidisciplinary care to improve not only surgical and cancer-related outcomes but also to impact patients' QoL and functional outcomes as well. However, as demonstrated in the SIOG/SSO survey, physicians are not routinely following these recommendations in their practices. Therefore, efforts should be again made to ensure that surgeons are adopting these recommendations and to pursue further study, in particular on functional and QoL outcomes, in this population.

Disclosure Statement

No conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Zulman DM, Sussman JB, Chen X, Cigolle CT, Blaum CS, Hayward RA. Examining the evidence: a systematic review of the inclusion and analysis of older adults in randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:783–790. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1629-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutten HJ, den Dulk M, Lemmens VE, van de Velde CJ, Marijnen CA. Controversies of total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer in elderly patients. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:494–501. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Angelis R, Sant M, Coleman MP, Francisci S, Baili P, Pierannunzio D, Trama A, Visser O, Brenner H, Ardanaz E, Bielska-Lasota M, Engholm G, Nennecke A, Siesling S, Berrino F, Capocaccia R, EUROCARE-5 Working Group Cancer survival in Europe 1999–2007 by country and age: results of EUROCARE-5 - a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:23–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70546-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Cancer Intelligence Network Major Resections by Cancer Site, in England; 2006 to 2010. National Cancer Intelligence Network short report. www.ncin.org.uk/about_ncin/major_resections.

- 5.Ghignone F, van Leeuwen BL, Montroni I, Huisman MG, Somasundar P, Cheung KL, Audisio RA, Ugolini G. The assessment and management of older cancer patients: a SIOG surgical task force survey on surgeons' attitudes. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huisman MG, van Leeuwen BL, Ugolini G, Montroni I, Spiliotis J, Stabilini C, de'Liguori Carino N, Farinella E, de Bock GH, Audisio RA. ‘Timed Up & Go’: a screening tool for predicting 30-day morbidity in onco-geriatric surgical patients? A multicenter cohort study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.PACE participants; Audisio RA, Pope D, Ramesh HS, Gennari R, van Leeuwen BL, West C, Corsini G, Maffezzini M, Hoekstra HJ, Mobarak D, Bozzetti F, Colledan M, Wildiers H, Stotter A, Capewell A, Marshall E. Shall we operate? Preoperative assessment in elderly cancer patients (PACE) can help. A SIOG surgical task force prospective study. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;65:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hempenius L, Slaets JP, van Asselt DZ, Schukking J, de Bock GH, Wiggers T, van Leeuwen BL. Interventions to prevent postoperative delirium in elderly cancer patients should be targeted at those undergoing nonsuperficial surgery with special attention to the cognitive impaired patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:28–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fong TG, Tulebaev SR, Inouye SK. Delirium in elder adults: diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:210–220. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mohri Y, Inoue Y, Tanaka K, et al. Prognostic nutritional index predicts postoperative outcome in colorectal cancer. World J Surg. 2013;37:2688–2692. doi: 10.1007/s00268-013-2156-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Terret C, Zulian GB, Naiem A, Albrand G. Multidisciplinary approach to the geriatric oncology patient. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1876–1881. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.3291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaiser MJ, Bauer JM, Ramsch C, Uter W, Guigoz Y, Cederholm T, Thomas DR, Anthony PS, Charlton KE, Maggio M, Tsai AC, Vellas B, Sieber CC. Frequency of malnutrition in older adults: a multinational perspective using the mini nutritional assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:1734–1738. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schiesser M, Kirchhoff P, Muller MK, Schäfer M, Clavien PA. The correlation of nutrition risk index, nutrition risk score, and bioimpedance analysis with postoperative complications in patients undergoing gastrointestinal surgery. Surgery. 2009;145:519–526. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barbosa LR, Lacerda-Filho A, Barbosa LC. Immediate preoperative nutritional status of patients with colorectal cancer: a warning. Arq Gastroenterol. 2014;51:331–336. doi: 10.1590/S0004-28032014000400012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Stijn MF, Korkic-Halilovic I, Bakker MS, van der Ploeg T, van Leeuwen PA, Houdijk AP. Preoperative nutrition status and postoperative outcome in elderly general surgery patients: a systematic review. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2013;37:37–43. doi: 10.1177/0148607112445900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rencozugullari A, Bnelice C, Valente M, Abbas M, Remzi F, Gorgun E. Predictors of anastomotic leak in elderly patients after colectomy: nomogram-based assessment from the American College of Surgeon National Surgical Quality Program Procedure-targeted cohort. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60:527–536. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chow WB, Rosenthal RA, Merkow RP, Ko CY, Esnaola NF, American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program; American Geriatrics Society Optimal preoperative assessment of the geriatric surgical patient: a best practices guideline from the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program and the American Geriatrics Society. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215:453–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silver JK, Baima J. Cancer prehabilitation: an opportunity to decrease treatment-related morbidity, increase cancer treatment options, and improve physical and psychological health outcomes. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2013;92:715–727. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31829b4afe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carli F, Charlebois P, Stein B, Feldman L, Zavorsky G, Kim DJ, Scott S, Mayo NE. Randomized clinical trial of prehabilitation in colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1187–1197. doi: 10.1002/bjs.7102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jack S, West M, Grocott MP. Perioperative exercise training in elderly subjects. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1187–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santa Mina D, Clarke H, Ritvo P, Leung YW, Matthew AG, Katz J, Trachtenberg J, Alibhai SM. Effect of total-body prehabilitation on postoperative outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2014;100:196–207. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li C, Carli F, Lee L, Charlebois P, Stein B, Liberman AS, Kaneva P, Augustin B, Wongyingsinn M, Gamsa A, Kim DJ, Vassiliou MC, Feldman LS. Impact of a trimodal prehabilitation program on functional recovery after colorectal cancer surgery: a pilot study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1072–1082. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2560-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deiner S, Westlake B, Dutton RP. Patterns of surgical care and complications in elderly adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62:829–835. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Søreide K, Wijnhoven B. Surgery for the aging population. Br J Surg. 2016;103:e7–9. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Desserud KF, Veen T, Søreide K. Emergency general surgery in the geriatric patient. Br J Surg. 2016;103:e52–61. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunn J, Lynch B, Rinaldis M, Pakenham K, McPherson L, Owen N, Leggett B, Newman B, Aitken J. Dimensions of quality of life and psychosocial variables most salient to colorectal cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2006;15:20–30. doi: 10.1002/pon.919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weaver KE, Forsythe LP, Reeve BB. Mental and physical health-related quality of life among U.S. cancer survivors: population estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:2108–2117. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banks E, Byles J, Gibson RE. Is psychological distress in people living with cancer related to the fact of diagnosis, current treatment or level of disability? Findings from a large Australian study. Med J Aust. 2010;193:S62–S67. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03931.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cornish JA, Tilney HS, Heriot AG. Personalized surgery for elderly CRC patients. A meta-analysis of quality of life for abdominoperineal excision of rectum versus anterior resection for rectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:2056–2068. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9402-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bossema ER, Seuntiëns MW, Marijnen CA. The relation between illness cognitions and quality of life in people with and without a stoma following rectal cancer treatment. Psychooncology. 2011;20:428–434. doi: 10.1002/pon.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gabriel SE, Normand SL. Getting the methods right - the foundation of patient-centered outcomes research. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:787–790. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1207437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fernando HC, Landreneau RJ, Mandrekar SJ, Nichols FC, DiPetrillo TA, Meyers BF, Heron DE, Hillman SL, Jones DR, Starnes SL, Tan AD, Daly BD, Putnam JB. Analysis of longitudinal quality-of-life data in high-risk operable patients with lung cancer: results from the ACOSOG Z4032 (Alliance) multicenter randomized trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149:718–725. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng MA, McMillan DT, Crowell K. Geriatric assessment in surgical oncology: a systematic review. J Surg Res. 2015;193:265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaklitsch MT. ‘How am I doing? Just ask me!’ The usefulness of patient self-reported quality of life in thoracic surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;149:663–664. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.11.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fiteni F, Vernerey D, Bonnetain F, Vaylet F, Sennélart H, Trédaniel J, Moro-Sibilot D, Herman D, Laizé H, Masson P, Derollez M, Clément-Duchêne C, Milleron B, Morin F, Zalcman G, Quoix E, Westeel V. Prognostic value of health-related quality of life for overall survival in elderly non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Eur J Cancer. 2016;52:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fournier E, Jooste V, Woronoff AS, Quipourt V, Bouvier AM, Mercier M. Health-related quality of life is a prognostic factor for survival in older patients after colorectal cancer diagnosis: a population-based study. Dig Liver Dis. 2016;48:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]