Abstract

Background and study aims

Investigations for lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) include flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, computed tomographic angiography (CTA), and angiography. All may be used to direct endoscopic, radiological or surgical treatment, although their optimal use is unknown. The aims of this study were to determine the diagnostic and therapeutic yields of endoscopy, CTA, and angiography for managing LGIB, and their influence on rebleeding, transfusion, and hospital stay.

Patients and methods

A systematic search of MEDLINE, PubMed, EMBASE, and CENTRAL was undertaken to identify randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and nonrandomized studies of intervention (NRSIs) published between 2000 and 12 November 2015 in patients hospitalized with LGIB. Separate meta-analyses were conducted, presented as pooled odds (ORs) or risk ratios (RR) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

Two RCTs and 13 NRSIs were included, none of which examined flexible sigmoidoscopy, or compared endotherapy with embolization, or investigated the timing of CTA or angiography. Two NRSIs (57 – 223 participants) comparing colonoscopy and CTA were of insufficient quality for synthesis but showed no difference in diagnostic yields between the two interventions. One RCT and 4 NRSIs (779 participants) compared early colonoscopy (< 24 hours) with colonoscopy performed later; meta-analysis of the NRSIs demonstrated higher diagnostic and therapeutic yields with early colonoscopy (OR 1.86, 95 %CI 1.12 to 2.86, P = 0.004 and OR 3.08, 95 %CI 1.93 to 4.90, P < 0.001, respectively) and reduced length of stay (mean difference 2.64 days, 95 %CI 1.54 to 3.73), but no difference in transfusion or rebleeding.

Conclusions

In LGIB there is a paucity of high-quality evidence, although the limited studies on the timing of colonoscopy suggest increased rates of diagnosis and therapy with early colonoscopy.

Introduction

Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding (LGIB) has an estimated incidence of 33/100 000 but is associated with greater resource use than upper GI bleeding 1 . The management of LGIB involves determining the source of bleeding in order to direct the most appropriate intervention to achieve hemostasis. There are multiple choices of intervention, including flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, computed tomographic angiography (CTA), mesenteric angiography, and nuclear scintigraphy. The diagnostic and subsequent therapeutic yields are unclear and are likely to be influenced by multiple patient factors 2 3 and the timing of intervention 4 . There is little evidence in the literature informing the optimal use of these interventions; hence, the development of recommendations in guidelines is limited 5 .

As well as diagnosis, endoscopy offers endotherapy, including adrenaline injection, thermocoagulation or clipping. Extravasation of contrast on CTA or mesenteric angiography may identify bleeding that is amenable to embolization. Compared with colonoscopy, CTA is better tolerated by patients but may identify a source only where there is active bleeding 6 . Delays between CTA and angiography may lead to a blush on CTA becoming nonapparent on a subsequent mesenteric angiogram 7 .

Given uncertainties around the optimum initial approach to investigation and management, we conducted a systematic review of the diagnostic and therapeutic yields of flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, CTA, and mesenteric angiography for LGIB. This takes the form of several direct head-to-head comparisons between modalities, each of which is reported separately, aiming to mirror the clinical questions encountered by clinicians involved in the acute management of LGIB.

Patients and methods

This review was registered on the PROSPERO register of systematic reviews (CRD42016025100) and conducted in accordance with the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement 8 and Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group 9 .

Search strategy

We searched MEDLINE, PubMed, EMBASE, CDSR, CENTRAL, DARE, HTA, NHSEED, ClinicalTrials.gov, and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform for articles published between 1 January 2000 and 12 November 2015 without language restrictions (see Appendix 1 for search strategy). The search was limited to publications since 2000 owing to the more recent adoption of CTA and therapeutic endoscopy, reflective of modern day practice.

Study eligibility

Eligible studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies (nonrandomized studies of intervention [NRSIs]). As there is variation in the reporting quality of NRSIs, those with a cohort design without methodological concordance were screened to ascertain whether they met the criteria to be categorized as a cohort study as described by Dekkers et al. 10 .

Adults hospitalized with acute LGIB of any cause were eligible. Studies of upper GI bleeding or pediatric populations were ineligible. LGIB was defined as “the onset of hematochezia originating from either the colon or the rectum” 5 . This can manifest as red or maroon blood, or melena 11 . As the focus of this review was the immediate investigation and treatment of LGIB, studies of patients who had completed first-line investigations (colonoscopy, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and radiological studies) without a proven source of bleeding, such as those with obscure GI bleeding 12 , were excluded.

Interventions included flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, CTA, mesenteric angiography, therapeutic endoscopy, and mesenteric embolization. Comparisons were grouped into three themes: choice of investigation, timing of investigation, and choice of treatment. Choice of investigation comparisons comprised: flexible sigmoidoscopy vs. CTA, colonoscopy vs. CTA, colonoscopy/flexible sigmoidoscopy vs. other (e. g. standard care), CTA vs. other. Timing of investigation comprised early vs. late flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, CTA, and mesenteric angiography in relation to presentation with bleeding. To maximize study eligibility we did not pre-specify “early” and “late.” Choice of treatment comprised endoscopic hemostasis vs. embolization, endoscopic hemostasis vs. other (e. g. surgery), and embolization vs. other. Specific types of endoscopic therapy were also compared. Where applicable, subgroups populated by hemodynamic status were also compared.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes were diagnostic and therapeutic yields. Therapeutic yield was defined as the proportion of participants that received hemostatic therapy, either during or after the intervention. Secondary outcomes were rebleeding, red blood cell transfusion, length of hospital stay, mortality, and complications related to the intervention.

Two reviewers screened studies and extracted data independently. Study screening and data extraction were performed using Covidence Systematic Review Software (Veritas Heath Innovation Ltd., Melbourne, Australia).

Risk of bias in RCTs and NRSIs was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool 13 and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale 14 , respectively.

Statistical analysis

Continuous outcomes were compared using mean difference and 95 % confidence intervals (CIs). Dichotomous outcomes were analyzed using risk ratio (RR) and 95 %CI for RCTs, and odds ratio (OR) and 95 %CI for NRSIs. Where the number of observed events was small, Peto OR and 95 %CI were used.

RCTs and NRSIs were analyzed separately 13 . NRSIs were deemed comparable if they had a Newcastle-Ottawa score ≥ 8 15 . Meta-analysis was conducted to calculate pooled RR, OR or mean difference, and 95 %CI for each comparator. Statistical heterogeneity was analyzed using I 2 statistics, and values > 50 % were considered to be significantly heterogeneous 16 . We used random effects modeling for all NRSIs and presented OR regardless of heterogeneity. No tests for funnel plot asymmetry were undertaken, as the number of studies in each comparison was fewer than 10 13 . Meta-analysis was undertaken using Review Manager 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Results

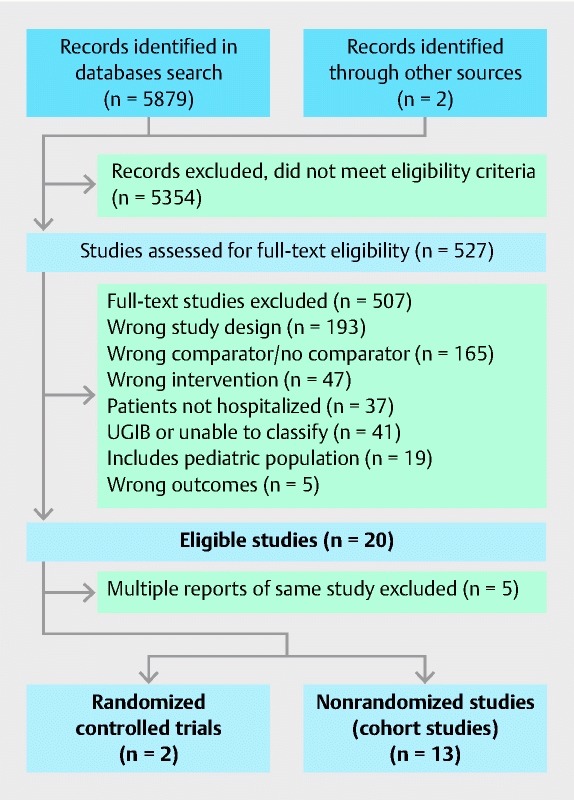

Searches identified 5879 potentially eligible references and 40 from 2410 prescreened records ( Fig. 1 ). On full-text review, 507 studies were excluded (reasons shown in Fig. 1 ) leaving 2 RCTs, 13 NRSIs, and 2 ongoing studies, including 6 conference abstracts 17 18 19 20 21 22 .

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart. UGIB, upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

Characteristics of reviewed studies

There was a lack of data across all interventions and comparators, notably no RCTs or NRSIs comparing embolization with endoscopic hemostasis. There were no studies that included flexible sigmoidoscopy as a comparator. Comparisons between colonoscopy and CTA were limited to nonrandomized data ( Table 1 ). A total of 10 studies compared different interventions and five examined different timings of the same intervention. Case definitions of LGIB are included in Appendix 2 . A total of 11 studies included patients with LGIB of any cause 4 18 19 20 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 and four were limited to patients with diverticular bleeding 17 21 22 30 . The number of participants enrolled in each study ranged from 72 to 100 in the RCTs, and from 27 to 326 in the NRSIs.

Table 1. Summary of evidence by comparison investigated and study methodology.

| Comparator | RCTs [ref] | NRSIs [ref] | Ongoing trials |

| Choice of investigation | |||

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy vs. CTA | None | None | |

| Flexible sigmoidoscopy vs. other | None | None | |

| Colonoscopy vs. CTA | None | Nagata 2015 26 Yabutani 2014 21 | |

| Colonoscopy vs. other (e. g. standard care) | Green 2005 4 | Yamaguchi 2006 23 | |

| CTA vs. other | None | Ketwaroo 2012 18 Sun 2011 20 Jacovides 2015 25 | |

| Diagnostic mesenteric angiography vs. other | None | None | |

| Timing of first-line investigation | |||

| Colonoscopy: Early (< 24 hours) vs. late (> 24 hours) | Laine 2010 | Abeldawi 2014 24 Nagata 2016 27 Strate 2003 28 Rodriguez-Moranta 2007 19 | |

| Radiology: A) Urgent CTA vs. nonurgent B) Urgent mesenteric angiography vs. nonurgent | None None | None None | |

| Choice of treatment | |||

| Therapeutic endoscopy vs. mesenteric embolization | None | None | |

| Therapeutic endoscopy vs. other | None | Jensen 2000 30 | Matsuhashi JPRN-UMIN000008287 |

| Embolization vs. other | None | None | |

| Endoscopic agent A vs. B | None | Nakano 2015 22 Ishii 2011 17 | Barkun NCT02135627 |

RCT, randomized controlled trials; NRSI, nonrandomized studies of intervention; CTA, computed tomographic angiography.

Most studies were conducted in older patients and, where reported, anticoagulant, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and particularly antiplatelet use was common. Only four studies reported baseline hemodynamic status 4 26 27 29 .

Choice of investigation

Colonoscopy vs. CTA

No RCTs compared colonoscopy with CTA. The two eligible NRSIs were retrospective, one comparing early colonoscopy and CTA (within 24 hours of admission) with early colonoscopy alone in 223 participants 26 , and one comparing early colonoscopy with CTA (timings not defined) in a single cohort of 57 patients with diverticular bleeding who underwent both tests 21 .

The was no difference in the diagnostic yield of CTA combined with colonoscopy vs. colonoscopy alone (OR 1.31, 95 %CI 0.26 to 6.63), although the diagnosis of lesions with active bleeding, adherent clot or visible vessels was higher in the CTA group (OR 2.14, 95 %CI 1.16 to 3.95, 223 participants) 26 . Patients in this group subsequently received more endoscopic hemostatic treatment (OR 3.47, 95 %CI 1.74 to 6.91), but there was no difference in terms of rebleeding (OR 1.08, 95 %CI 0.51 to 2.28) or the number of participants receiving transfusion (OR 1.71, 95 %CI 0.86 to 3.39). Mortality, length of hospital stay, and complications were not reported. The study by Yabutani et al. 21 described only diagnostic yield, demonstrating no difference between CTA and colonoscopy (OR 1.36, 95 %CI 0.63 to 2.95, 57 participants).

Colonoscopy vs. other

We identified one RCT 4 that randomized 100 patients to colonoscopy within 8 hours or standard care (red cell scanning, angiography or elective colonoscopy). The diagnostic yield was higher in the group randomized to urgent colonoscopy (RR 1.91, 95 %CI 1.03 to 3.53), but there was no difference in therapeutic yield (endoscopic hemostasis or vasopressin infusion at angiography: RR 1.7, 95 %CI 0.87 to 3.34) or rebleeding (RR 0.73, 95 %CI 0.37 to 1.44), although volume of transfusion was smaller in the urgent colonoscopy group (mean difference – 0.8 units, 95 %CI – 0.62 to – 0.98). We identified one NRSI 23 : a study of 111 participants who underwent ultrasound followed by colonoscopy. The diagnostic yield of colonoscopy was superior to that of ultrasound (OR 3.78, 95 %CI 2.07 to 6.91).

CTA vs. other

No RCTs were identified. The three eligible NRSIs all compared CTA with nuclear scintigraphy; two retrospective cohort studies of 92 – 99 participants 18 20 , and one before and after study of a protocol that prioritized CTA over nuclear scintigraphy in 161 participants 25 . Ketwaroo et al. 18 demonstrated a higher diagnostic yield with the use of CTA (OR 4.03, 95 %CI 1.67 to 9.72, 92 participants) but the study by Sun et al. 20 reported no difference between modalities (OR 0.49, 95 %CI 0.20 to 1.21, 99 participants). Neither study reported therapeutic yield for both study arms or any of the secondary outcomes. The protocol study by Jacovides et al. 25 demonstrated no difference in diagnostic yield (OR 0.85, 95 %CI 0.33 to 2.19), therapeutic yield (defined as embolization during first mesenteric angiography, OR 1.10, 95 %CI 0.55 to 2.20) or length of hospital stay (mean difference 3 days, 95 %CI – 16.58 to 22.58).

Diagnostic mesenteric angiography vs. other

We found no studies that included mesenteric angiography as a first-line intervention.

Timing of first-line investigation

Colonoscopy

One RCT 29 , one prospective 19 , and three retrospective NRSIs 24 27 28 compared early and late colonoscopy. The RCT by Laine et al. included 72 patients. The NRSI ranged from 57 to 326 participants. Early colonoscopy was defined as within 12 hours by one study 29 and within 24 hours by three studies 19 24 27 . One study subdivided cohorts into consecutive 12 hours groups 28 . For the purpose of this comparison, early colonoscopy is defined as that performed within 24 hours of admission.

When assessing diagnostic yield, three studies categorized diverticula 27 28 29 or hemorrhoids 28 29 as a definite (based on the presence of active bleeding or stigmata of recent hemorrhage) or presumptive (presence of diverticulosis or hemorrhoids without bleeding in absence of other potential bleeding sources) cause of bleeding. Rodriguez-Moranta et al. 19 reported only definite diagnoses, but did not define these, and Albeldawi et al. 24 did not define diagnosis.

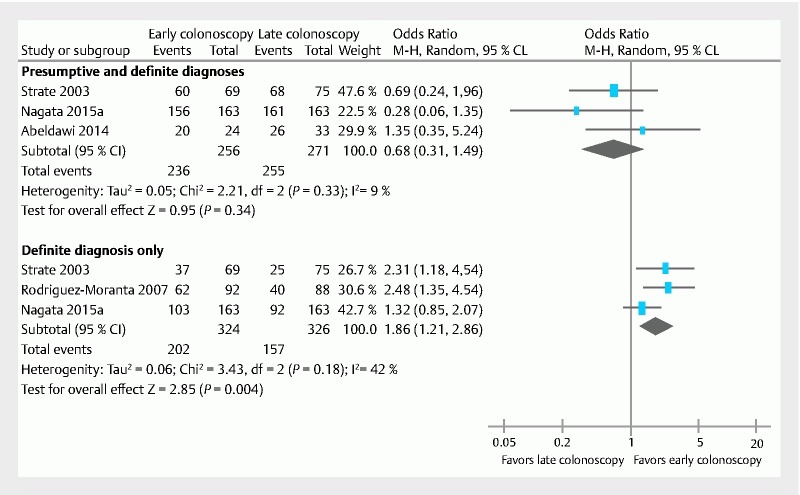

When presumptive and definite diagnoses are included in diagnostic yield, no difference was observed between early vs. late colonoscopy in the RCT (RR 1.17, 95 %CI 0.87 to 1.56) or pooled analysis of the NRSIs (OR 0.68, 95 %CI 0.31 to 1.49, 3 studies, 527 participants, I 2 = 9 %, Fig. 2 ). When diagnostic yield was limited to definite diagnoses, early colonoscopy was associated with a higher diagnostic yield in the NRSIs (OR 1.86, 95 %CI 1.21 to 2.86, 3 studies, 527 participants I 2 = 42 %, Fig. 2 ), although this was not significant in the RCT (RR 1.12, 95 %CI 0.70 to 1.78).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of comparison of nonrandomized studies of intervention. Upper: Presumptive plus definite diagnoses. Lower: Definite diagnoses only. Definitive diagnoses were defined by the presence of stigmata of recent hemorrhage or active bleeding, plus the diagnosis of an underlying cause. CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

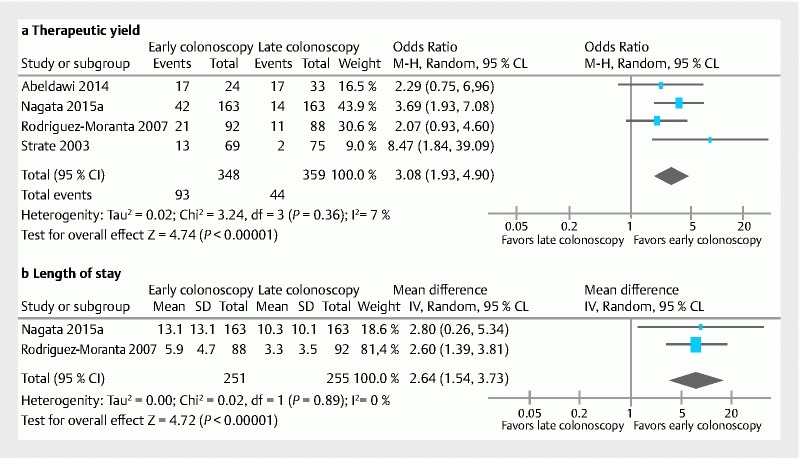

All studies defined therapeutic yield as the number of participants receiving endoscopic therapy. All employed endoscopic hemostasis with a minimum of three available modalities (clipping, banding, thermocoagulation, argon plasma coagulation, adrenaline injection), the specific type depending on pathology and endoscopist preference. The therapeutic yield was superior in the early colonoscopy group in the pooled analysis of the NRSIs (OR 3.08, 95 %CI 1.93 to 4.90, 4 studies, 707 participants I 2 = 7 %, Fig. 3a ), but no different in the RCT (RR 1.0, 95 %CI 0.36 to 2.81).

Fig. 3.

Forest of plot of comparison of nonrandomized studies of intervention. a Therapeutic yield. b Length of hospital stay. CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel.

Rebleeding was reported in the RCT 29 and two NRSIs 24 27 , but all varied in their definition ( Table 2 ) so were not pooled. There was no difference in rebleeding between early and late colonoscopy in the RCT (RR 1.6, 95 %CI 0.58 to 4.43, 72 participants), or the NRSIs (Nagata et al. OR 1.96, 95 %CI 0.94 to 4.11, 326 participants, and Albeldawi et al. OR 0.7, 95 %CI 0.2 to 2.44, 57 participants).

Table 2. Interstudy variability of the definition of rebleeding.

| Study [ref] | Definition of rebleeding |

| Green 2005 4 | Hematochezia (defined as any one of > 3 bloody bowel movements in < 8 hours, ICU admission, > 5 % decrease in Hct in < 12 hours, transfusion of > 3 units RBC, hemodynamic instability in previous 6 hours defined as angina, syncope, pre-syncope, orthostatic vital signs, MAP < 80 mmHg or HR > 110) after clinical cessation of the index bleeding event |

| Laine 2010 29 | Hematochezia persisting for > 24 hours, recurrent hematochezia after initial resolution (e. g. brown stool followed by hematochezia), HR > 100 or SBP < 100 mmHg after hemodynamic stability for ≥ 1 hour, or hemoglobin drop > 2 g/dL after stable hemoglobin values ≥ 3 hours apart |

| Nagata 2016 27 | Significant amounts of fresh bloody or wine-colored stools after index colonoscopy with unstable vital signs; SBP ≤ 90 mmHg or HR ≥ 110 or the need for blood transfusion |

| Strate 2003 28 | Blood per rectum after 24 hours of stability accompanied by a drop in Hct ≥ 20 %, and/or a requirement of additional blood transfusions |

| Abeldawi 2014 24 | After clinical cessation of index bleeding event during hospitalization |

| Nagata 2015 26 | Significant fresh bloody or wine-colored stool accompanied by unstable vital signs; SBP ≤ 90 mmHg or HR ≥ 110 and nonresponse to ≥ 2 units transfused blood |

| Jensen 2000 30 | Self-limited or recurrent hematochezia that required no more than an additional 2 units of packed red cells or continued or recurrent hematochezia that required at least 3 units of packed red cells |

| Ishii 2011 17 | Clinical evidence of recurrent bleeding |

ICU, intensive care unit; Hct, hematocrit; RBC, red blood cells; MAP, mean arterial pressure; HR, heart rate; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Transfusion was reported in the RCT 29 and one NRSI 27 ; patients in the early group of the RCT received more transfusions (mean difference 0.8 units, 95 %CI 0.65 to 0.95, 72 participants), but in the NRSI there was no difference in the number of participants receiving transfusion (OR 1.00, 95 %CI 0.62 to 1.63, 326 participants).

Mean length of hospital stay was reported in three studies 19 27 29 . Early colonoscopy was associated with a shorter hospital stay in NRSIs (mean difference 2.64 days, 95 %CI 1.54 to 3.73, two studies, 506 participants, I 2 = 0 %) and in the RCT (mean difference 0.40 days, 95 %CI 0.06 to 0.74, 72 participants) ( Fig. 3b ).

Adverse events were reported in two studies 27 29 . Laine et al. 29 reported one perforation in the late colonoscopy group (RR 0.33, 95 %CI 0.01 to 7.92). Nagata et al. 27 reported no major colonoscopy-related adverse events in either cohort. Mortality was reported in two studies 24 29 . There were no deaths in the study by Albeldawi et al. 24 , but there were two deaths in the urgent colonoscopy arm in the RCT by Laine et al. (RR 5.00, 95 %CI 0.25 to 1.00). One patient developed a fatal intracranial hemorrhage, and the other required prolonged hospitalization due to medical co-morbidities and died after a cardiorespiratory arrest.

CTA and mesenteric angiography

We found no studies comparing early vs. late CTA or mesenteric angiography.

Choice of treatment

Therapeutic endoscopy vs. mesenteric embolization

We found no studies.

Therapeutic endoscopy vs. other

One NRSI compared endoscopic therapy (adrenaline injection or thermocoagulation) with a historical control comprising conservative or surgical treatment in patients with diverticular bleeding 30 . Patients who received endoscopic treatment were less likely to require surgery for bleeding (Peto OR 0.14, 95 %CI 0.02 to 0.88, 27 participants), rebleed (Peto OR 0.10, 95 %CI 0.02 to 0.51) or receive a transfusion (Peto OR 0.10, 95 %CI 0.02 to 0.51). We identified one ongoing RCT comparing endoscopic therapy with barium impaction for diverticular bleeding (Matsuhashi et al, JPRN-UMIN000008287).

Mode of endoscopic hemostasis

No RCTs were identified. Two retrospective NRSIs were identified, both comparing endoscopic band ligation with endoclipping in diverticular bleeding 17 22 . The primary outcome in both studies was re-bleeding; Ishii et al. 17 reported 60-day rates of 1/16 (6.2 %) for endoscopic band ligation and 16/48 (33.3 %) for endoclipping, although this was not significantly different (OR 7.50, 95 %CI 0.91 to 61.94, 64 participants). In the endoclipping group, seven patients required radiological control of bleeding vs. none in the endoscopic band ligation group; however, this was not significant (Peto OR 4.37, 95 %CI 0.72 to 26.37). Nakano et al. 22 followed patients for 2 years and also found that large numbers of patients re-bled in each group (endoscopic band ligation 24/50, 48.0 %; endoclipping 18/39, 46.2 %), although there was no difference between the two modalities (OR 0.93 95 %CI 0.40 to 2.15, 89 participants). Need for further procedure was not reported. No patient experienced complications related to endoscopy in either study.

We identified one ongoing RCT comparing TC-325 (Hemospray) monotherapy at endoscopy with standard endoscopic therapy in patients with upper GI bleeding or LGIB due to malignancy (Barkun et al., NCT02135627).

Hemodynamic status

We identified no RCTs, NRSIs or ongoing trials that compared flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, CTA or mesenteric angiography in groups stratified by hemodynamic status.

Assessment of methodological quality

Both RCTs were deemed at high or unclear risk of bias due to blinding ( Table 3 ). Laine et al. stated that their trial was not blinded. Green et al. also stated that the physicians caring for the patients were not blinded and gave no detail on blinding of outcome assessors. The nature of the interventions used in these studies makes blinding difficult. For subjective outcomes such as diagnostic yield this may introduce significant bias.

Table 3. Assessment of methodological quality (Cochrane risk of bias for RCTs, Newcastle-Ottawa for NRSIs).

| RCT [ref] | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel | Blinding of outcome assessors | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting | Other |

| Green 2005 4 | Low | Unclear | High | Unclear | Low | Unclear | Low |

| Laine 2010 29 | Low | Low | High | High | Low | Low | High |

| NRSI [ref] | Representativeness (1) | Selection of non-exposed (1) | Ascertainment of exposure (1) | Outcome of interest not present at start of study (1) | Comparability (2) | Assessment of outcome (1) | Follow-up long enough and adequate (2) |

| Adeldawi 2014 24 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1/0 | 1 | 1/1 |

| Ishii 2011 17 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0/0 | 1 | 1/1 |

| Jacovides 2015 25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0/1 | 1 | 1/1 |

| Jensen 2000 30 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0/0 | 1 | 1/1 |

| Nagata 2016 27 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1/1 | 1 | 1/1 |

| Nagata 2015 26 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1/0 | 1 | 1/1 |

| Nakano 2015 22 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0/0 | 1 | 1/0 |

| Sun 2011 20 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0/0 | 1 | 1/1 |

| Yabutani 2014 21 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1/1 | 1 | 1/1 |

| Yamaguchi 2006 23 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1/1 | 1 | 1/1 |

| Ketwaroo 2012 18 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0/0 | 1 | 1/1 |

| Strate 2003 28 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1/1 | 1 | 1/1 |

| Rodriguez-Moranta 2007 19 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1/1 | 1 | 1/1 |

Rebleeding may also be subject to bias due to lack of blinding. Additionally, there was considerable interstudy variation in the definition of rebleeding in the eight studies that reported this outcome ( Table 2 ). Most studies used a definition that included a period of clinical stability 4 28 29 , although some did not define the criteria that would need to be met to establish a new bleeding event 17 24 . Three studies characterized rebleeding by the persistence of ongoing signs of bleeding without a period of stability 26 27 30 , but these definitions may have also captured patients with failed hemostatic intervention, rather than true rebleeding.

One study did not define rebleeding 22 .

The study by Laine et al. was subject to “other” source of bias, as it was terminated early because the hospital changed its protocol on allowing colonoscopy in the emergency room, although the reasons for this were not given.

Risk of bias in the NRSIs was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa scale. The two most common areas of poor performance in the NRSIs were selection of participants, particularly representativeness of the exposed, and comparability of cohorts. Six studies scored poorly for representativeness of LGIB as they studied a single pathology 17 21 22 30 or a single intervention that was related to severity of bleeding 18 20 . This limits interstudy comparability and the generalizability of these results to the LGIB population as a whole.

Three studies did not include data on whether they adjusted for confounders 17 18 20 , one study provided no data on confounders and also populated one treatment arm using an intervention that is likely to be related to severity of bleeding (endoscopic hemostasis) 30 , and one study compared baseline demographics for each group, but did not include cardiovascular parameters or baseline transfusion requirements 22 . There are likely to be significant baseline imbalances between the cohorts in these studies. None were deemed of sufficient quality to permit data synthesis.

Discussion

There is considerable uncertainty regarding the optimal management of LGIB 5 . This is a comprehensive review encompassing all of the major diagnostic and treatment modalities for LGIB, and demonstrating a lack of evidence across the majority of interventions. The area with the most evidence is timing of colonoscopy, with meta-analysis suggesting higher diagnostic yields, rates of hemostasis, and a reduction in the length of hospital stay with early colonoscopy.

Colonoscopy has been recommended as the first-line diagnostic procedure for LGIB 5 , but questions remain regarding its timing and suitability for all patients.

We found that the use of CTA with colonoscopy may enhance the identification of bleeding lesions when compared with colonoscopy alone. Although this did translate into increased use of hemostatic therapy, there was no or minimal impact upon clinically important outcomes such as rebleeding or transfusion. CTA is often reserved for unstable patients that do not respond to resuscitation 5 , but we found no studies comparing it with other interventions in exclusively shocked patients.

Although colonoscopy performed within 24 hours of admission was associated with higher rates of diagnosis, hemostasis, and a reduction in length of hospital stay, there was no evidence that it had any impact upon death or rebleeding. Paradoxically, there was higher red blood cell transfusion in the early colonoscopy arm of the RCT, although this may represent baseline imbalances between arms, as the initial hemoglobin was also lower in the early arm 29 . Most of the studies on timing of colonoscopy were nonrandomized, and conducted in patients who were subsequently diagnosed with diverticular bleeding, limiting the generalizability of these findings. Timing of colonoscopy has been the focus of three recent systematic reviews. Kouanda et al. and Seth et al. included RCTs and cohort studies, but differed in their classification of several large database studies that we rejected as case series, or restricted their search to English language studies 31 32 . Nonetheless, the authors reported similar findings: there was no difference in rates of rebleeding, death or transfusion. In contrast to the present review, Seth et al. reported that there was no difference in therapeutic yield or hospital stay with early colonoscopy. For therapeutic yield, the authors did not include data from Albeldawi et al. in the meta-analysis, but the reasons for this are not clear. For length of hospital stay, the authors pooled estimates from RCTs with NRSIs, which may account for the different findings from the current review. Sengupta et al. used a similar study classification system to that used in the present review, and also pooled estimates from RCTs and NRSIs, but also reported no difference in clinical outcomes with early colonoscopy 15 .

The use of colonoscopy in real-life practice is variable. In a recent nationwide audit of 143 hospitals in the UK, colonoscopy was performed in only 4 % patients with LGIB, with a median waiting time of 4 days (range 2 – 8) 33 . As there were no major barriers identified to the routine availability of colonoscopy, this is likely to reflect uncertainty regarding its utility in the acute setting. In contrast to upper GI bleeding, colonoscopy in the acute setting can be challenging to perform, requires rapid bowel preparation, and may be poorly tolerated by the patient. Only two studies reported complications, but overall early colonoscopy appeared to be safe. In one RCT, two patients who received urgent colonoscopy died 29 . Although neither was attributed to the intervention, the potential to cause harm in patients with extensive co-morbidities should not be underestimated.

The impact of early colonoscopy on hospital stay has clear benefits. A microcosting analysis of upper GI bleeding admissions reported an average cost of £ 2458 per patient, most of which was due to the cost of the hospital bed 34 . Not all patients with LGIB will require urgent investigation, however. In the UK, 48 % of admitted patients have a benign course and require no inpatient investigation 33 . The most frequent outpatient investigation is lower GI endoscopy, 70 % of which is scheduled to be performed more than 2 weeks post-discharge 33 . The value of such delayed intervention requires further research.

Outcomes other than length of hospital stay must also be considered. Rebleeding following endoscopic hemostasis was reported in 6 % – 48 % patients in the cohort studies 17 22 27 , raising questions regarding the efficacy of endoscopic hemostasis. This is important given the absence of evidence comparing it with other treatment options, notably embolization. The two studies comparing modes of endoscopic hemostasis were limited to patients with diverticular bleeding. Considering that bleeding stops spontaneously in over 80 % of patients 35 , this may not be the group that will derive the most benefit.

There are important questions regarding the value of colonoscopy in LGIB beyond diagnosis. Most therapeutic techniques originate in the upper GI tract and may be unsuitable for lesions in the colon and rectum. Endotherapy relies on the identification of stigmata of recent hemorrhage to localize and treat the bleeding source, but this can be subjective, as demonstrated by the differing diagnostic yields between lesions that were defined as a presumptive vs. a definitive source. This is particularly relevant to diverticular bleeding, the most common cause of LGIB in the UK 33 . It can be difficult to identify the culprit diverticula, and treatment of one will not guarantee prevention of bleeding from another. Evaluation of the current management of LGIB is limited by the lack of baseline data for comparison: national observational studies have only been conducted since 2000 1 33 36 , and there are currently no national guidelines on the management of LGIB in the UK. It is therefore not possible to compare current management with historical practice and to establish whether newer interventions such as CTA have made an impact.

There are several limitations to this review. Most evidence originates from NRSIs, with significant bias, which limits the strength of the conclusions that can be drawn from the review. More randomized data, particularly on the timing of colonoscopy, are urgently required, especially in view of the recent publication of risk scores focussing on increasing the outpatient management of LGIB 37 . Systematic review of NRSIs is limited by the variable description of study methodology, making their classification difficult. This is evidenced by the different studies that are included in reviews of the same topic with similar inclusion criteria 15 31 32 . A new study comparing CTA with colonoscopy was published 38 after the searches for the current review were completed in 2015, and the results may be relevant to this topic and warrant an update of the present review in the future. We limited the search to studies published since 2000, as before this date routine use of endotherapy and embolization were in their infancy, and studies were mostly limited to case reports and safety studies. Relevant studies published prior to this period may have been missed therefore.

In summary, although there was a paucity of high-quality evidence across most interventions, we found that colonoscopy within 24 hours had higher diagnostic and therapeutic yields, and a shorter hospital stay. The value of colonoscopy after hospital discharge requires further appraisal, in addition to further research into the identification of patients who will gain the greatest benefit from early colonoscopy. Additional areas of research should focus on the clinical outcomes of endoscopic hemostasis, particularly comparisons with mesenteric embolization.

Appendix 1: Search strategy

The following databases were searched for systematic reviews, RCTs and observational (cohort) studies, from 2000 onwards, on 12.11.15:

MEDLINE (OvidSP, 1946 onwards)

PubMed (epublications only)

Embase (OvidSP, 1974 onwards)

CDSR, CENTRAL, DARE, HTA & NHSEED (The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 3)

Transfusion Evidence Library

Ongoing Trials:

ClinicalTrials.gov 159 refs

WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform: 36 refs

N.B. The Data Providers of the ICTRP Search Portal currently are:

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ANZCTR) Brazilian Clinical Trials Registry (ReBec) Chinese Clinical Trial Register (ChiCTR) Clinical Research Information Service (CRiS), Republic of Korea

ClinicalTrials.gov

Clinical Trials Registry – India (CTRI)

Cuban Public Registry of Clinical Trials (RPCEC)

EU Clinical Trials Register (EU-CTR)

German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS)

Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT)

ISRCTN.org

Japan Primary Registries Network (JPRN)

Pan African Clinical Trial Registry (PACTR)

Sri Lanka Clinical Trials Registry (SLCTR)

The Netherlands National Trial Register (NTR)

Searches retrieved 10,667 references plus 195 ongoing trials, which were reduced to 8,260 refs plus 87 ongoing trials when duplicates had been removed.

SEARCH STRATEGIES

MEDLINE (OvidSP)

exp Lower Gastrointestinal Tract/

exp Intestines/

Gastrointestinal Tract/

exp Mesenteric Arteries/

(lower gastrointestinal tract* or lower gastro-intestinal tract* or lower GI tract* or large intestin* or small intestin* or mesenteric arter*).tw,kf.

or/1 – 5

(h?emorrhag* or bleed* or re-bleed* or rebleed* or blood loss*).mp.

6 and 7

exp Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage/

((anal or anus or rectum or rectal or colon or colonic or colorectal or cecum or caecum or jejunum or cloaca or gut or ileum or diverticula* or lower intestin* or large intestin* or small intestin* or bowel or lower gastrointestinal or lower gastro-intestinal or lower GI or mesenteric) adj6 (h?emorrhag* or bleed* or re-bleed* or rebleed* or blood loss*)).tw,kf.

(hematochezia or mel?ena or colonic angiodysplasia or proctorrhagi* or rectocolic* or rectorrhagi*).tw,kf.

or/8 – 11

exp Colonoscopy/

Proctoscopy/

(colonoscop* or coloscop* or sigmoidoscop* or proctoscop* or rectoscop* or enteroscop* or anuscop*).tw,kf.

Endoscopy, Gastrointestinal/

Capsule Endoscopy/

(endoscop* adj3 (capsule or video or lower or mesenteric or colon* or bowel)).tw,kf.

pillcam.tw,kf.

or/13 – 19

Colonography, Computed Tomographic/

((CT or computed or tomograph* or virtual) adj2 (colonograph* or colonoscop* or pneumocolon*)).tw,kf.

Tomography, X-Ray Computed/

Radiology, Interventional/

(tomograph* angiogra* or CTA or CT angiogra* or mesenteric angiogra* or GI angiogra* or (radiolog* adj2 (diagnos* or intervention*))).tw,kf.

Angiography/

or/21 – 26

Hemostasis, Endoscopic/

((therap* or treatment* or h?emosta* or epinephrine or adrenaline or cyanoacrylate or inject* or band* or electrocauter* or argon plasma or thermal coagulat* or thermocoagulat* or thermo-coagulat* or heater probe* or argon coagulat* or laser coagulat* or YAG laser or ablat* or h?emoclip* or h?emospray or sclerotherap*) adj10 endoscop*).tw,kf.

(endotherap* or endoclip* or over-the-scope clip*).tw,kf.

20 or 28 or 29 or 30

Embolization, Therapeutic/

(emboli?ation or emboli?ed or embolotherap* or angioemboli* or microemoboli*).tw,kf.

27 or 32 or 33

12 and (31 or 34)

limit 35 to yr = "2000 -Current"

EMBASE (OvidSP)

exp Large Intestine/

exp Small Intestine/

exp Anus/

exp Mesenteric Artery/

Intestine/

Gastrointestinal Tract/

(lower gastrointestinal tract* or lower gastro-intestinal tract* or lower GI tract* or large intestin* or small intestin* or mesenteric arter*).tw.

1 or 2 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7

(h?emorrhag* or bleed* or re-bleed* or rebleed*or blood loss*).mp.

Bleeding/

9 or 10

8 and 11

Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage/ or Colon Hemorrhage/ or Hemorrhagic Colitis/ or Intestinal Bleeding/ or Intestine Hematoma/ or Large Intestine Hemorrhage/ or Melena/ or Rectum Hemorrhage/ or Small Intestine Hemorrhage/

((anal or anus or rectum or rectal or colon or colonic or colorectal or cecum or caecum or jejunum or cloaca or gut or ileum or diverticula* or lower intestin* or large intestin* or small intestin* or bowel or lower gastrointestinal or lower gastro-intestinal or lower GI or mesenteric) adj6 (h?emorrhag* or bleed* or re-bleed* or rebleed* or blood loss*)).tw.

(hematochezia or mel?ena or colonic angiodysplasia or proctorrhagi* or rectocolic* or rectorrhagi*).tw.

or/12 – 15

Intestine Endoscopy/ or Capsule Endoscopy/ or Colonoscopy/ or Push Enteroscopy/ or Rectoscopy/ or Sigmoidoscopy/

Gastrointestinal Endoscopy/

(colonoscop* or coloscop* or sigmoidoscop* or proctoscop* or rectoscop* or enteroscop* or anuscop* or pillcam*).tw.

(endoscop* adj3 (capsule or video or lower or mesenteric or colon* or bowel)).tw.

or/17 – 20

*Endoscopy/ and *Hemostasis/

((therap* or treatment* or h?emosta* or epinephrine or adrenaline or cyanoacrylate or inject* or banded or banding or electrocauter* or argon plasma or thermal coagulat* or thermocoagulat* or thermo-coagulat* or heater probe* or argon coagulat* or laser coagulat* or YAG laser or ablat* or h?emoclip* or h?emospray or sclerotherap*) adj10 endoscop*).tw.

(endotherap* or endoclip* or over-the-scope clip*).tw.

or/21 – 24

Computed Tomographic Colonography/

((CT or computed or tomograph* or virtual) adj2 (colonograph* or colonoscop* or pneumocolon*)).tw.

Computer Assisted Tomography/

Interventional Radiology/

(tomograph* angiogra* or CTA or CT angiogra* or mesenteric angiogra* or GI angiogra* or (radiolog* adj2 (diagnos* or intervention*))).tw.

Abdominal Angiography/ or Superior Mesenteric Angiography/

Pelvic Angiography/

or/26 – 32

Artificial Embolism/

(emboli?ation or emboli?ed or embolotherap* or angioemboli* or microemoboli*).tw.

or/33 – 35

16 and (25 or 36)

PubMed (epublications only)

#1 (lower gastrointestinal tract* OR lower gastro-intestinal tract* OR lower GI tract* OR large intestin* OR small intestin* OR mesenteric arter*) AND (hemorrhag* OR haemorrhag* OR bleed* OR re-bleed* OR rebleed* OR blood loss*)

#2 ((anal OR anus OR rectum OR rectal OR colon OR colonic OR colorectal OR cecum OR caecum OR jejunum OR cloaca OR gut OR ileum OR diverticula* OR lower intestin* OR large intestin* OR small intestin* OR bowel OR lower gastrointestinal OR lower gastro-intestinal OR lower GI OR mesenteric) AND (hemorrhag* OR haemorrhage* OR bleed* OR re-bleed* OR rebleed* OR blood loss*))

#3 (hematochezia OR melena OR melaena OR colonic angiodysplasia OR proctorrhagi* OR rectocolic* OR rectorrhagi*)

#4 #1 OR #2 OR #3

#5 (colonoscop* OR coloscop* OR sigmoidoscop* OR proctoscop* OR rectoscop* OR anuscop* OR pillcam OR endotherap* OR endoclip* OR over-the-scope clip*)

#6 ((capsule OR video OR lower OR mesenteric OR colon OR colonic OR bowel OR hemosta* OR haemostat* OR epinephrine OR adrenaline OR cyanoacrylate OR inject* OR banded OR banding OR electrocauter* OR argon plasma OR thermal coagulat* OR thermocoagulat* OR thermo-coagulat* OR heater probe* OR argon coagulat* OR laser coagulat* OR YAG laser OR ablat* OR hemoclip* OR hemospray OR sclerotherap*) AND endoscop*)

#7 #5 OR #6

#8 ((CT OR computed OR tomograph* OR virtual) AND (colonograph* OR colonoscop* OR pneumocolon*))

#9 (tomograph* angiogra* OR CTA OR CT angiogra* OR mesenteric angiogra* OR GI angiogra* OR (radiolog* AND (diagnos* OR intervention*)))

#10 (embolization OR embolized OR embolization OR embolised OR embolotherap* OR angioemboli* OR microemoboli*)

#11 #8 OR #9 OR #10

#12 #4 and (#7 OR #11)

#13 ((random* OR blind* OR "control group" OR placebo* OR controlled OR cohort* OR nonrandom* OR observational OR retrospective* OR prospective* OR comparative OR comparator OR groups OR trial* OR "systematic review" OR "meta-analysis" OR metaanalysis OR "literature search" OR medline OR cochrane OR embase) AND (publisher[sb] OR inprocess[sb] OR pubmednotmedline[sb]))

#14 #12 and #13

TRANSFUSION EVIDENCE LIBRARY

Clinical Specialty: Gastrointestinal Disorders

Subject Area: Red Cells

ClinicalTrials.gov

Conditions/Search Terms: GI bleeding OR lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage OR colorectal bleeding OR colonic bleeding OR intestinal bleeding OR rectal bleeding OR mesenteric bleeding OR hematochezia OR melena OR bowel bleeding OR diverticular bleeding

Interventions: endoscopy OR colonoscopy OR CT OR tomography OR proctoscopy OR endoclip OR colonography OR angiography OR embolization OR capsule OR pillcam

ICTRP

Conditions/Search Terms: GI bleeding OR lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage OR colorectal bleeding OR colonic bleeding OR intestinal bleeding OR rectal bleeding OR mesenteric bleeding OR hematochezia OR melena OR bowel bleeding OR diverticular bleeding

Interventions: endoscopy OR colonoscopy OR CT OR tomography OR proctoscopy OR endoclip OR colonography OR angiography OR embolization OR capsule OR pillcam

Results

Relevant references: 5850

Possibly irrelevant references: 2410 (contain one or more of the following words in the title: upper (not lower), abdominal aortic aneurysm, cancer, malignan*, carcinoma*, esophageal, duodenal, hepatic, cirrho*, stomach, liver, transplant*, varice*, pancreat*)

These have been screened by one reviewer (KO) and identified 40 possible relevant references. These have been added to the ‘relevant references’ for full screening by two reviewers.

Appendix 2: Study characteristics

| Study (Country) [ref] | Design | Study years | Study population | Interventions | Participants, n | Age, mean ± SD, years | Shock * , n (%) | Medications on admission, n (%) | ||

| Anticoagulants | Antiplatelets | NSAIDs | ||||||||

| Green 2005 (USA) 4 | RCT | 1993 – 1995 | Patients admitted with hematochezia with clinical or laboratory evidence of significant blood loss | Colonoscopy < 8 hours after admission | 50 | 68 ± 3 | 30 (60.0) | NR | NR | 29 (60.0) |

| Standard care: red cell scan if ongoing bleeding, colonoscopy | 50 | 71 ± 4 | 34 (68.0) | NR | NR | 26 (52.0) | ||||

| Laine 2010 (USA) 29 | RCT | 2002 – 2008 | Patients admitted with hematochezia with a high-risk feature* | Colonoscopy < 12 hours after admission | 36 | 52 ± 3 | 27 (75.0) | NR | NR | NR |

| Colonoscopy 36 – 60 hours after admission | 36 | 52 ± 2 | 31 (86.1) | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Albeldawi 2014 (USA) 24 | Retrospective cohort | 2011 – 2012 | All acute LGIB | Colonoscopy < 24 hours after admission | 24 | 66.8 ± 13.8 | NR | 2 (8.3) | 13 (54.2) | 2 (8.3) |

| Colonoscopy > 24 hours after admission | 33 | 69.3 ± 11.1 | NR | 7 (21.2) | 19 (57.6) | 3 (9.1) | ||||

| Ishii 2011 (Japan) 17 | Retrospective cohort | 2004 – 2010 2009 – 2010 | Patients with colonic diverticular hemorrhage | EBL | 16 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Endoclipping | 48 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Jacovides 2015 (USA) 25 | Historical control | 2005 – 2012 | All patients hospitalized with LGIB | Historical protocol: red cell scan, CTA or colonoscopy | 78 | 68 ± 15 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| New protocol: CTA, colonoscopy | 83 | 70 ± 15 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Jensen 2000 (USA) 30 | Historical control | 1986 – 1992 and 1994 – 1998 | Patients with hematochezia and diverticulosis | Medical and surgical intervention | 17 | 66 ± 3 | NR | NR | NR | 3 |

| Medical and endoscopic therapy | 10 | 67 ± 4 | NR | NR | NR | 3 | ||||

| Nagata 2016 (Japan) 27 | Retrospective cohort | 2009 – 2014 | All patients admitted with acute overt LGIB | Colonoscopy < 24 hours after admission | 163 | 67.9 ± 17.4 | 17 (10.4) | 9 (5.5) | 63 (38.7) | 23 (14.1) |

| Colonoscopy > 24 hours after admission | 163 | 66.4 ± 16.9 | 19 (11.7) | 6 (11.7) | 54 (33.1) | 20 (12.3) | ||||

| Nagata 2015 (Japan) 26 | Retrospective Cohort | 2008 – 2013 | Patients admitted with LGIB who underwent colonoscopy | Urgent CTA then colonoscopy | 126 | 68.3 ± 16.5 | 5 (4.0) | 7 (5.6) | 55 (43.7) | 33 |

| Colonoscopy < 24 hours after admission | 97 | 67.7 ± 16.5 | 1 (1.0) | 4 (4.1) | 36 (37.1) | 13 (13.4) | ||||

| Nakano 2015 (Japan) 22 | Retrospective cohort | 2004 – 2014 | Patients undergoing endoscopic therapy for colonic diverticular hemorrhage | EBL | 50 | 67 ± 13 | NR | NR | 15 | 4 |

| Endoclipping | 39 | 64 ± 13 | NR | NR | 13 | 3 | ||||

| Sun 2011 (USA) 20 | Retrospective cohort | 2007 – 2008 and 2008 – 2010 | All patients hospitalized with acute GI bleeding | CTA | 53 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Red cell scan | 46 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Yabutani 2014 (Japan) 21 | Single retrospective cohort | 2010 – 2012 | Patients diagnosed with diverticular bleeding | CTA and colonoscopy | 57 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Yamaguchi 2006 (Japan) 23 | Single retrospective cohort | 1999 – 2004 | Consecutive patients with hematochezia | Ultrasound and colonoscopy | 111 | 58 (range 18 – 96) | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Ketwaroo 2012 (USA) 18 | Retrospective cohort | 2010 – 2011 | Suspected acute LGIB | CTA | 46 | 68.2 ± 17 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Red cell scan | 46 | 70 ± 15 | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Strate 2003 (USA) 28 | Retrospective cohort – subgroup | 1996 – 1999 | All patients admitted with ICD-9 codes representing LGIB, or a wide range of diagnoses associated with LGIB | Colonoscopy < 24 hours after admission | 69 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Colonoscopy > 24 hours after admission | 75 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||

| Rodriguez- Moranta 2007 (Spain) 19] | Prospective cohort | 2005 – 2006 | Consecutive patients admitted with LGIB | Colonoscopy < 24 hours after admission | 92 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Colonoscopy > 24 hours after admission | 88 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||

CTA, computed tomographic angiography; EBL, endoscopic band ligation; GI, gastrointestinal; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; LGIB, lower gastrointestinal bleeding; NR, not reported; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; RCT, randomized controlled trial

High risk features defined as heart rate > 100, systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg, orthostatic changes in systolic blood pressure > 20 mmHg or in heart rate > 20 beats/min, blood transfusion, or drop in hemoglobin ≥ 1.5 g/dL within a 6-hour period.

Acknowledgment

James East was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Footnotes

Competing interests None

References

- 1.Lanas A, Garcia-Rodriguez L A, Polo-Tomas M et al. Time trends and impact of upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation in clinical practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1633–1641. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheffel H, Pfammatter T, Wildi S et al. Acute gastrointestinal bleeding: detection of source and etiology with multi-detector-row CT. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:1555–1565. doi: 10.1007/s00330-006-0514-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardin F, Andreotti A, Martella B et al. Current practice in colonoscopy in the elderly. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2012;24:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Green B T, Rockey D C, Portwood G et al. Urgent colonoscopy for evaluation and management of acute lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2395–2402. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strate L L, Gralnek I M.ACG Clinical Guideline: Management of patients with acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding Am J Gastroenterol 2016111459–474.Erratum in Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111: 755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strate L L, Naumann C R. The role of colonoscopy and radiological procedures in the management of acute lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh F H, Soong J, Lieske B et al. Does the timing of an invasive mesenteric angiography following a positive CT mesenteric angiography make a difference? Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:57–61. doi: 10.1007/s00384-014-2055-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269, w264. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stroup D F, Berlin J A, Morton S C et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dekkers O M, Egger M, Altman D G et al. Distinguishing case series from cohort studies. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:37–40. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-1-201201030-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gralnek I M, Neeman Z, Strate L L. Acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding. NEJM. 2017;376:1054–1063. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1603455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raju G S, Gerson L, Das A et al. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1697–1717. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins J GS. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Book Series. 2008:392–432. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sengupta N, Tapper E B, Feuerstein J D. Early versus delayed colonoscopy in hospitalized patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2017;51:352–359. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins J P, Thompson S G, Deeks J J et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ishii N, Fujita Y. Endoscopic treatment for colonic diverticular hemorrhage: from endoscopic clipping to endoscopic band ligation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:AB292. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ketwaroo G A, Tewani S K, Kheraj R et al. Mesenteric CT angiography in the evaluation and management of acute lower GI bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:S581. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez-Moranta F, Berrozpe A, Botargues J M et al. Colonoscopy delay in lower gastrointestinal bleeding: influence on diagnostic accuracy, endoscopic therapy and hospital stay. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:AB261. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun J, Khandelwal N, Wong R. CT angiography is superior to tagged red blood cell scanning for localizing GI bleeding and for guiding management. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:S82. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yabutani A, Tomisato K, Teramoto A et al. Possible utility of contract enhanced computed tomography for detecting colonic diverticular bleeding by emergent colonoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29 03:307–308. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nakano K, Ishii N, Fujita Y. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic band ligation versus endoscopic clipping for treatment of colonic diverticular hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:AB370. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1392510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaguchi T, Manabe N, Hata J et al. The usefulness of transabdominal ultrasound for the diagnosis of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1267–1272. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Albeldawi M, Ha D, Mehta P et al. Utility of urgent colonoscopy in acute lower gastro-intestinal bleeding: a single-center experience. Gastroenterol Rep. 2014;2:300–305. doi: 10.1093/gastro/gou030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacovides C L, Nadolski G, Allen S R et al. Arteriography for lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage: role of preceding abdominal computed tomographic angiogram in diagnosis and localization. JAMA Surgery. 2015;150:650–656. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagata N, Niikura R, Aoki T et al. Role of urgent contrast-enhanced multidetector computed tomography for acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding in patients undergoing early colonoscopy. J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:1162–1172. doi: 10.1007/s00535-015-1069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagata N, Niikura R, Sakurai T et al. Safety and effectiveness of early colonoscopy in management of acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding on the basis of propensity score matching analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:558–564. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strate L L, Syngal S. Timing of colonoscopy: impact on length of hospital stay in patients with acute lower intestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:317–322. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laine L, Shah A. Randomized trial of urgent vs. elective colonoscopy in patients hospitalized with lower GI bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2636–2641. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jensen D M, Machicado G A, Jutabha R et al. Urgent colonoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of severe diverticular hemorrhage. NEJM. 2000;342:78–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001133420202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kouanda A M, Somsouk M, Sewell J L et al. Urgent colonoscopy in patients with lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:107–117 e1. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seth A, Khan M A, Nollan R et al. Does urgent colonoscopy improve outcomes in the management of lower gastrointestinal bleeding? Am J Med Sci. 2017;353:298–306. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2016.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oakland K, Guy R, Uberoi R et al. Acute lower GI bleeding in the UK: patient characteristics, interventions and outcomes in the first nationwide audit. Gut. 2017 doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell H E, Stokes E A, Bargo D et al. Costs and quality of life associated with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the UK: cohort analysis of patients in a cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007230. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cirocchi R, Grassi V, Cavaliere D et al. New trends in acute management of colonic diverticular bleeding: a systematic review. Medicine. 2015;94:e1710. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strate L L, Ayanian J Z, Kotler G et al. Risk factors for mortality in lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1004–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oakland K, Jairath V, Uberoi R et al. Derivation and validation of a novel risk score for safe discharge after acute lower gastrointestinal bleeding: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/s2468-1253(17)30150-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clerc D, Grass F, Schafer M et al. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding – computed tomographic angiography, colonoscopy or both? World J Emerg Surg. 2017;12:1. doi: 10.1186/s13017-016-0112-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]