Abstract

Background

Personality dysfunction represents one of the only predictors of differential response between active treatments for depression to have replicated. In this study, we examine whether depressed patients with higher neuroticism scores, a marker of personality dysfunction, show differences versus depressed patients with lower scores in the functioning of two brain regions associated with treatment response, the anterior cingulate and anterior insula cortices.

Methods

Functional magnetic resonance imaging data during an emotional Stroop task were collected from 135 adults diagnosed with major depressive disorder at four academic medical centers participating in the Establishing Moderators and Biosignatures of Antidepressant Response for Clinical Care (EMBARC) study. Secondary analyses were conducted including a sample of 28 healthy individuals.

Results

In whole-brain analyses, higher neuroticism among depressed adults was associated with increased activity in and connectivity with the right anterior insula cortex to incongruent compared to congruent emotional stimuli (ks>281, ps<0.05 FWE corrected), covarying for concurrent psychiatric distress. We also observed an unanticipated relationship between neuroticism and reduced activity in the precuneus (k=269, p<0.05 FWE corrected). Exploratory analyses including healthy individuals suggested that associations between neuroticism and brain function may be nonlinear over the full range of neuroticism scores.

Conclusions

This study provides convergent evidence for the importance of the right anterior insula cortex as a brain-based marker of clinically meaningful individual differences in neuroticism among adults with depression. This is a critical next step in linking personality dysfunction, a replicated clinical predictor of differential antidepressant treatment response, with differences in underlying brain function.

Keywords: Neuroticism, Major Depressive Disorder, fMRI, Right Anterior Insula, Precuneus, Emotion Regulation

Introduction

Neuroticism reflects the tendency to experience negative emotions and to cope poorly with affective states (1). High levels of neuroticism have enormous public health consequences, including impairments in work functioning (2) increased medical treatment utilization (2), and reduced longevity (3). Neuroticism is a strong vulnerability marker for the development of depression (4–9), but critically - the clinical effects of neuroticism do not stop once an episode of depression emerges. To the contrary, markers of dysfunctional personality, including high levels of neuroticism, represent one of the only replicated prescriptive indicators of differential response between active treatments for depression (10–12). That is, among depressed individuals, individual differences in neuroticism and personality functioning exist and these differences have consequences for the likelihood that a given treatment will be effective. Specifically, higher levels of neuroticism (12) and frank comorbid personality disorder (11) have each been associated with superior response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) compared to cognitive therapy, two generally effective treatments for depression (13). These patterns are reinforced by evidence that SSRI treatments may have strong specific effects, compared to placebo, in reducing levels of neuroticism itself, over and above changes in symptoms (14,15). Although personality dysfunction does not invariably predict differential response across all forms of treatment (see, 16,17), no other patient characteristic in the depression treatment outcome literature has so often been related to differential response across active treatments. The neural mechanisms driving these effects, however, are unknown.

Neuroticism was initially conceptualized as a genetically-based, biologically-driven trait associated with heightened reactivity in limbic systems to stressors in the environment (18,19). Recent work has revealed associations between neuroticism and the functioning of the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC) and right anterior insula (rAI), regions implicated in the processing and regulation of emotionally relevant information (20–23). Haas and colleagues (24), for example, observed increased activity in the sgACC in healthy adults as a function of neuroticism during an emotional Stroop task. There are several reasons why individuals with higher levels of neuroticism may perform differently on such a task. The incongruent condition of an emotional Stroop requires participants to manage competing, emotionally salient elements of the stimulus, control attentional resources in the presence of a distractor, and select the appropriate response while suppressing a competing response. Even with non-emotional stimuli, neuroticism is associated with general difficulties in the control of attentional resources, which manifests in tasks involving attention capture, selective attention, and the disengagement of attention from distracting information (25–27). These effects may be further exacerbated when stimuli are negative (27) or emotionally-relevant, given the salience of such information (28,29). Further, there is mounting evidence suggesting that neuroticism may also be associated with individual differences in neural activity in a key part of the salience network. Together with more dorsal portions of the ACC, the rAI is believed to be a critical region involved in salience detection (22,23). Increased activity in the rAI has been associated with neuroticism in healthy samples across a wide-variety of emotionally relevant tasks for which salience detection is a key feature, including loss anticipation (30), emotion processing (31), pain perception (32), and decision making (33,34).

Converging evidence from treatment trials examining patterns of brain activity associated with response to treatments for depression suggest key roles for individual differences in the functioning of the sgACC and rAI in predicting differential treatment outcomes. Specifically, several observational treatment studies suggest that higher activity in the sgACC (both at rest and during tasks) is associated with better response to antidepressant medications (see, 35), whereas lower sustained activity during emotion processing is associated with better response to cognitive therapy (36,37). By contrast, the sole randomized controlled trial examining neural predictors of treatment outcome did not observe that the sgACC differentiated response to antidepressant and cognitive therapy treatments. Rather, the rAI was the region that most clearly predicted differential response: those with higher metabolism in this region at rest were more likely to remit with drug treatment and less likely to remit with cognitive therapy, and vice versa (38).

In this study, we used functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) to examine whether depressed individuals with high levels of neuroticism (versus depressed individuals with lower levels of neuroticism) displayed increased activity in the sgACC and rAI during a variant of the face/word emotional Stroop task. Activity in both brain regions has been associated with neuroticism and, separately with differential treatment response in depression. Tasks like the emotional Stroop that require cognitive and attentional control in the context of emotional processing reliably elicit activity in anterior insula and sgACC regions (39). Thus, the emotional Stroop provides a promising probe of the role of neuroticism in brain function in depression. This study is a first step to determine whether activity in these two brain regions might represent core neural markers of clinically meaningful individual differences in depression that may help to explain the association between personality dysfunction and differential treatment response. In secondary analyses, we incorporate data from a small sample of healthy control individuals to examine associations with neuroticism across the full range of neuroticism scores.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Study participants were recruited as part of the Establishing Moderators and Biosignatures of Antidepressant Response for Clinical Care (EMBARC) study, a multi-site randomized controlled trial examining medication treatment of depression (40,41). All data came from baseline assessments, prior to treatment. The initial sample comprised 190 individuals diagnosed with current major depressive disorder (MDD) who were not currently receiving treatment and who completed the fMRI task at one of the four scanning sites: Columbia University, Massachusetts General Hospital, the University of Michigan, and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. In secondary analyses, data from 40 healthy control (HC) individuals were incorporated to determine the effects of neuroticism across the full range of scores. Psychiatric diagnoses were made using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (42). Full inclusion/exclusion criteria have been reported elsewhere (41) and are described in the Supplement. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each site. All participants provided written informed consent.

Of the original sample, data from 49 MDD and 9 HC were excluded due to excessive motion (> 4 mm), low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR<80), technical issues, or artifacts in fMRI data. Three additional individuals with MDD were excluded due to poor behavioral performance (accuracy <70%), and three participants from each group were excluded due to missing data on core clinical measures. This yielded a final sample of 135 MDD and 28 HC, representing data loss of 28.9% and 30.0%, respectively, χ2(1)=0.02, p=0.89, consistent with other neuroimaging datasets (38).

Clinical Measures

Neuroticism was assessed using the NEO-Five-Factor Inventory-3 (43). Because neuroticism scores can be highly correlated with symptom measures (44), we covaried for psychiatric symptoms (see below). Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (45). Sub-scales of the Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire were used to assess anhedonia and anxious arousal (46,47).

Paradigm

The Emotional Conflict Task (48) was used as an emotional Stroop task to probe implicit emotion reactivity and regulation processes during the presentation of conflicting emotional information. Stimuli consisted of 148 pictures of emotional faces (happy or fearful), and participants were asked to label the expression while ignoring an emotion word (“happy” or “fear”) that overlaid the image. The emotion words either matched (congruent trials) or conflicted (incongruent trials) with the emotional face. Stimuli were presented for 1000ms, with a variable inter-stimulus interval (3000–5000ms, M=4000ms), in a pseudo-random order, counterbalanced as a function of expression, word, gender, and response button. Prior to the scan, participants practiced the task and were required to achieve > 85% accuracy.

Neuroimaging Data acquisition

Structural and functional MRI data were collected at each site using 3 Tesla MRI scanners. See Supplement for detailed acquisition parameters.

Functional Neuroimaging Data Preprocessing

Preprocessing of functional images was implemented using Nipype software (http://nipy.org/nipype), using a combination of modules from different software packages. The first five volumes of the run were discarded. Functional images were realigned using SPM8 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm), co-registered to the participant’s structural image and normalized to MNI space using a linear affine transformation implemented in FSL (http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/). MNI space was defined using the OASIS template (http://www.oasis-brains.org), with a resolution of 2mm isotropic. AFNI 3dDespike (http://afni.nimh.nih.gov/afni) was used to address spikes in signal intensity (using 3SD and 5SD cutoffs for spikes and deviations from the curve, respectively). Finally, data were spatially smoothed using an 8mm adaptive kernel (FSL).

Functional Neuroimaging Data Analyses

First-level models were estimated using SPM8. Models were fit separately for each participant and included regressors for each trial type, along with nuisance regressors representing the first trial of the block, error and post-error trials. Regressors were convolved with the canonical hemodynamic response function (HRF). Temporal derivatives of the HRF, and the 6 movement parameters, were included as variables of no interest. A high-pass filter (60s) was used. For the current study, the contrast between incongruent and congruent trials served as the comparison of interest (additional detail in the supplement).

Whole-brain voxel-wise analyses were conducted at the second level to examine between-persons effects. Consistent with prior EMBARC reports, all models covaried for scanning site, sex, and age. The primary aim of the study was to examine differences between MDD as a function of neuroticism. As such, the best control participants for examining neural function of individuals with MDD and high levels of neuroticism are individuals with MDD and lower levels of neuroticism. Thus, the primary whole-brain analyses focused exclusively on the effects of neuroticism in MDD. Because measures of neuroticism can be contaminated with current distress, we additionally covaried for current levels of depression, anhedonia, and anxiety. Secondary whole-brain analyses incorporated data from the HC group. The lack of overlap in neuroticism scores between the groups (S2) precluded us from examining the group-by-neuroticism interaction effect to determine whether the effect of neuroticism differed between the groups. In order to ascertain whether the effect of neuroticism was similar at the lower (HC) and higher (MDD) ends of the range, we included both linear and curvilinear (neuroticism2) terms in the model (additional details in the supplement).

Voxel-wise regression analyses were implemented using the GLM Flex suite of software tools (http://mrtools.mgh.harvard.edu/index.php/Main_Page). This software uses all available data to estimate the model in a given voxel. See S1 for a map of sample sizes per voxel (minimum N=32). Statistical inferences were made on the basis of cluster level statistics (cluster forming threshold p<0.005, uncorrected, extent threshold p<0.05 FWE corrected). Given that the size of the effect of neuroticism on neural function in depression is currently unknown, these thresholds were chosen a-priori as a way of balancing protection from both Type-I and II errors (49).

To explore whether neuroticism was also associated with differences in connectivity between brain regions, we conducted exploratory generalized psychophysiological interaction (gPPI; 50) analyses. Given the findings reported below, we used as the seed region a mask of the dorsal rAI derived from a relevant parcellation study of the insula (51). First- and second-level models were the same as those described above.

Clinical, Demographic and Behavioral Data Analyses

Associations with clinical, demographic, and behavioral data were examined with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Associations with neuroimaging data were examined using parameter estimates extracted from significant clusters of activity. Reaction time data were log-transformed when examined as the dependent variable. Differences in accuracy were examined using Poisson regression models of error rates, with robust standard errors where appropriate (52).

Results

Primary Analyses: Neuroticism in MDD

Clinical Features and Behavioral Results

Table 1 displays demographic and clinical characteristics. The distribution of neuroticism scores in the MDD group (S2) was centered (M=68.85, SD=7.86) nearly 2 SD higher than published population norms (M=50, SD=10) (43), consistent with the level and variability of neuroticism scores observed in previous depressed samples (53). Depression severity was the only variable significantly associated with neuroticism in the MDD group. As expected, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests of within-subject effects revealed that accuracy for the incongruent condition was lower than the congruent condition (p<0.001), and dependent t-tests revealed significantly slower reaction times to the incongruent compared to the congruent conditions (t(134)=20.25, p<0.001). Neuroticism was not significantly associated with behavior (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics.

| Variable | MDD (N=135) | HC (N=28) | Effect of Group | Association with Neuroticism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDD Group | Full Sample | ||||

| Demographic | |||||

| %Female | 67.41% | 60.71% | χ2(1)=0.46 | rpb=−0.02 | rpb=0.03 |

| %Married | 20.90%a | 17.86% | χ2(1)=0.13 | rpb=−0.17 | rpb=−0.06 |

| %Unemployedb | 48.06% | 23.08% | χ2(2)=6.39* | ρ=0.09 | ρ =0.20* |

| Age, M(SD) | 36.51 (12.56) | 37.39 (16.08) | t(161)=−0.32 | r=−0.11 | r=−0.10 |

| Years of Education, M(SD)c | 14.84 (2.46) | 15.82 (5.04) | t(29.71)=−1.01 | r=0.002 | r=−0.09 |

| IQ, M(SD)d | 114.85 (12.07) | 118.42 (13.07) | t(137)=−1.30 | r=0.003 | r=−0.08 |

| Behavioral Performance | |||||

| % Correct, Incongruente | 93.88% (5.15%) | 93.49% (5.17%) | Z=−0.37 | Z=−0.08 | Z=0.22 |

| % Correct, Congruente | 96.91% (3.86%) | 97.38% (2.76%) | Z=0.74 | Z=−0.15 | Z=0.94 |

| Reaction Time, Incongruent, M(SD)f | 782.59 (138.81) | 794.23 (186.48) | t(161)=−0.16 | r=0.07 | r=0.03 |

| Reaction Time, Congruent, M(SD)f | 718.36 (123.10) | 729.84 (164.55) | t(161)=−0.23 | r=0.05 | r=0.02 |

| Neuroticism, M(SD) | 68.85 (7.86) | 36.39 (7.24) | t(161)=20.15*** | - | - |

| HRSD, M(SD)c | 26.61 (5.50) | 0.71 (1.01) | t(160.17)=50.74*** | r=0.18* | r=0.79*** |

| MASQ-Anhedonia, M(SD)c | 43.77 (5.22) | 26.04 (7.95) | t(31.98)=11.31*** | r=0.14 | r=0.71*** |

| MASQ-Anxiety, M(SD)c | 17.67 (5.90) | 10.79 (0.99) | t(158.49)=12.73*** | r=0.13 | r=0.43*** |

| Clinical Features | |||||

| Duration of Episode (months), M(SD)g | 36.75 (60.90) | - | r=0.01 | ||

| Age of Onset (years), M(SD) | 16.13 (5.90) | - | r=−0.10 | ||

| % Recurrenth | 86.36% | - | rpb=−0.04 | ||

| % Melancholic | 38.52% | - | rpb=−0.06 | ||

| % Atypical | 30.37% | - | rpb=0.06 | ||

| % Current Anxiety Disorder | 37.04% | - | rpb=0.01 | ||

| % Current Eating Disorder | 1.48% | - | rpb=0.17 | ||

| % Lifetime Alcohol/Substance Disorder | 22.22% | 7.14% | Fisher's Exact: p=0.07 | rpb=0.08 | rpb=0.16* |

Note. MDD = Major Depressive Disorder, HC = Healthy Control, rpb = point biserial correlation.

Data were missing from 1 participant.

Data were missing from 2 participants (MDD group) and considered not classifiable as employed vs unemployed for 6 others (4 in the MDD Group, 2 in the HC group).

the Satterthwaite method was used due to inequality of variances.

Data were missing 20 MDD and 4 HC participants.

Due to the shape of the distributions, data were examined using Poisson regression models of error rates using robust standard errors.

Reaction time data were log-transformed for analyses.

Data were missing from 2 participants.

Data were missing from 3 participants.

HRSD=Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, MASQ Mood and Anxiety Symptoms Questionnaire,

p<0.05,

p<0.001

Task Effects

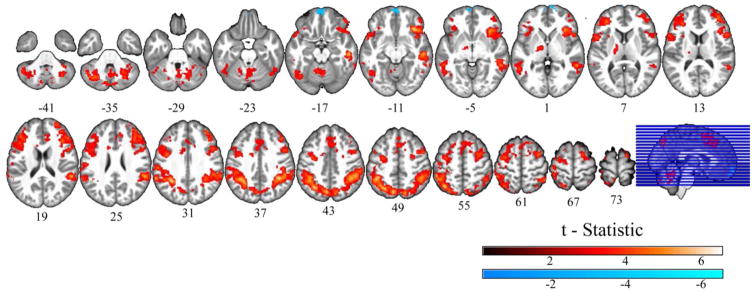

As expected, significantly greater BOLD response to incongruent, compared to congruent, stimuli was observed for the MDD group in the anterior insula cortex, cingulate, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (PFC), lateral parietal cortex, precuneus, and the thalamus, along with activity in motor regions, fusiform gyrus, cerebellum, and right middle temporal gyrus (Figure 1, Table 2). We also observed a significant negative effect (which represented greater negative relative BOLD signal during the incongruent compared to the congruent condition, Table 2) in the frontal pole.

Figure 1.

Neural Correlates of the Incongruence Effect in Major Depression. Significant clusters (p<0.05 FWE corrected) of blood oxygen level dependent response to the incongruent-minus-congruent contrast across the depressed group.

Table 2.

Coordinates of Clusters Showing Significant Task Effects among MDD (Incongruent - Congruent)

| K | FWE Corrected p | Region | t | x | y | z | Stimulus effects, M (SD)a | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incongruent | Congruent | ||||||||

| Positive Effect | |||||||||

| 20638 | <0.001 | R/L | Parietal (IPL, SMG, SPL, ANG, Precuneus) | 6.12 | 40 | −46 | 38 | 0.58 (1.16) | 0.23 (1.14) |

| R/L | Frontal (IFG, MFG, SFG, Precentral Gyrus, Postcentral Gyrus, Operculum) | ||||||||

| R | Temporal (MTG, STG) | ||||||||

| 2315 | <0.001 | R/L | Cerebellum | 4.61 | −14 | −54 | −20 | 2.21 (1.76) | 1.86 (1.72) |

| 1129 | <0.001 | L | Fusiform/MTG | 5.43 | −42 | −66 | −20 | 1.22 (1.42) | 0.94 (1.37) |

| 270 | 0.04 | L | Thalamus | 3.91 | −14 | −12 | 6 | 0.61 (1.08) | 0.38 (1.03) |

| Negative Effect | |||||||||

| 267 | 0.04 | - | Frontal Pole | −3.88 | 8 | 70 | 2 | −0.99 (2.23) | −0.57 (2.08) |

Note. The main effects of scanning site, sex, and age were covaried. Cluster forming threshold p<0.005 uncorrected, cluster extent threshold p<0.05 FWE corrected.

beta values for each stimulus type were extracted from the clusters and averaged over the MDD sample.

R=Right, L=Left, IPL=Inferior Parietal Lobule, SMG=Supramarginal Gyrus, SPL=Superior Parietal Lobule, ANG=Angular Gyrus, IFG=Inferior Frontal Gyrus, MFG=Middle Frontal Gyrus, SFG=Superior Frontal Gyrus, MTG=Middle Temporal Gyrus, STG=Superior Temporal Gyrus.

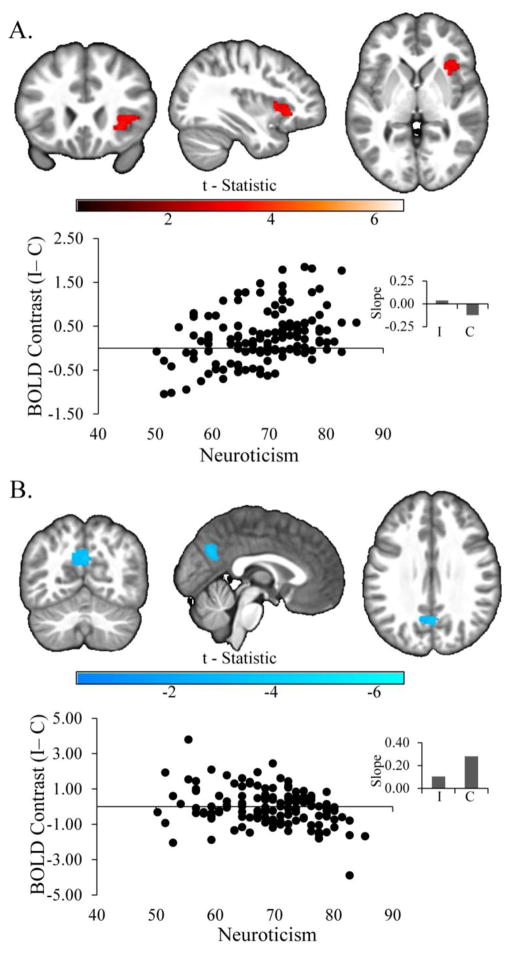

Effect of Neuroticism on BOLD Response

We observed a significant positive relationship in whole-brain analyses between neuroticism and activity in the dorsal rAI in MDD (Figure 2A; k=281, FWE corrected p=0.03, Peak: t=3.76 x=32, y=22, z=−2) to the incongruent compared to the congruent conditions, covarying for current depression, anhedonia, and anxiety symptoms. We also observed a significant negative relationship in the left precuneus (Figure 2B, k=269, FWE corrected p=0.04, Peak: t=−4.27 x=0, y=−64, z=30), due to a weaker positive relationship between neuroticism and BOLD response to the incongruent compared to the congruent conditions in this region (Figure 2B inset). Secondary analyses of extracted data revealed that the effect of neuroticism remained significant in both the rAI and precuneus regions (all Fs>5.51, all ps<0.03) when covarying for demographic and clinical variables (see the supplement for additional detail). Furthermore, we repeated the primary whole-brain models examining neuroticism on its own (see, 54,55), and observed two similar clusters: a significant cluster in the dorsal rAI that extended in the frontal operculum (k=419, FWE corrected p=0.004) and a cluster that was just shy of significance in the left precuneus (k=233, FWE corrected p=0.09).

Figure 2.

Effect of Neuroticism on BOLD Response in Major Depression. Significant clusters of positive (Panel A) and negative (Panel B) relationships between neuroticism and brain activity among adults with major depressive disorder, covarying for the effects of site, sex, age, depression, anhedonia, and anxiety. Scatter plots are provided for display purposes only. They depict the bivariate relationships between neuroticism (abscissa) and BOLD response in the significant clusters (ordinate), represented by the beta coefficient associated with the incongruent (I) - congruent (C) contrast. Insets display slope estimates (standardized βs from regression models of extracted data, covarying for the above variables) representing the relationship between neuroticism and BOLD response to each stimulus type.

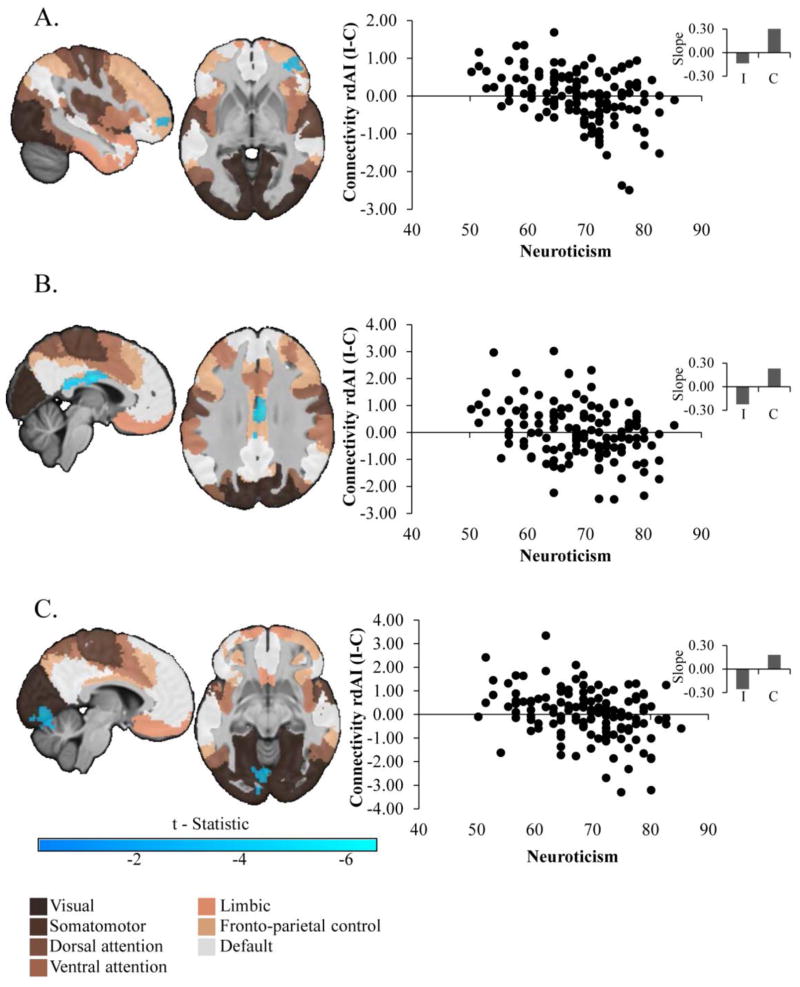

Effect of Neuroticism on Functional Connectivity

Given the findings in the dorsal rAI noted above, and given this region’s association with other large scale cortical networks, we utilized a dorsal rAI mask from a recent parcellation study of the insula as the seed region for whole-brain gPPI analyses (51), and we overlaid significant results on a map generated by a recent parcellation of large-scale cortical networks (56). We observed three significant clusters (Figure 3) demonstrating reduced connectivity with the dorsal rAI as a function of neuroticism to incongruent versus congruent stimuli: a cluster in the lateral PFC (lateral BA10) localized in a region associated with the fronto-parietal control network (k=287, FWE corrected p=0.03, Peak: t=−4.08 x=42, y=50, z=−2); a cluster in a thin strip of cortex in the inferior middle and posterior cingulate, also associated with the fronto-parietal control network (k=448, FWE corrected p=0.002, Peak: t=−5.01 x=4, y=−12, z=26); and a cluster in the occipital lobe, associated with the visual network, and extending ventrally into the cerebellum (k=1048, FWE corrected p<0.001, Peak: t=−4.45 x=−6, y=−78, z=−8). In each cluster, the negative association was due to reduced connectivity during incongruent and increased connectivity during congruent stimuli (Figure 3 inset). As above, the effect of neuroticism in each cluster remained significant when demographic and clinical variables were covaried, all Fs>13.80, all ps<0.001 (details in the supplement along with an analyses of the effects of scanner site).

Figure 3.

Effect of Neuroticism on Functional Connectivity with the Dorsal Right Anterior Insula in Major Depression. Significant clusters represent results of generalized psychophysiological interaction analyses using a dorsal right anterior insula seed derived from a recent parcellation study (51). To aid interpretation, clusters have been overlaid on the seven-network parcellation of large-scale cortical networks derived by (56). Scatter plots are provided for display purposes only. They depict the bivariate relationships between neuroticism (abscissa) and parameter estimates (ordinate) of the contrast in connectivity during the incongruent (I) versus congruent (C) conditions. Insets display slope estimates (standardized βs from regression models of extracted data, covarying for the above variables) representing the relationship between neuroticism and connectivity parameter estimates for each stimulus type.

Secondary Analyses: Neuroticism in the Combined MDD and HC samples

As displayed in Table 1, the HC and MDD groups were well matched on demographic variables, with the exception of employment rates (Table 1). Neuroticism levels among HC (M=36.39, SD=7.24) were substantially (≈1.5 SD) lower than population norms, likely due to strict inclusion criteria. In line with prior reports (e.g., 57,58), when the full range of clinical scores was considered across the full sample, neuroticism was significantly associated with depression, anhedonia, and anxiety symptoms, as well as employment status and past alcohol and substance abuse diagnoses (Table 1).

We used repeated measures linear and Poisson regression models to examine the effects of group, condition, and the group-by-condition interaction on reaction times and error rates, respectively. Incongruent stimuli were associated with longer reaction times (F(1,161)=267.90, p<0.001) and higher error rates (F(1,161)=25.40, p<.001) than congruent stimuli. Neither the main effect of group nor the group-by-condition interaction were significant in either analysis (All Fs<0.53, ps>0.46) Neuroticism was not associated with behavior in any condition, in either group (Table 1).

Effect of Neuroticism on BOLD Response across the Sample

In whole-brain analyses across the full sample, we did not observe a significant effect of group or a linear effect of neuroticism on BOLD response (all ks<190, FWE corrected p>0.05). Rather we observed a significant curvilinear relationship between neuroticism and BOLD response to the incongruent compared to the congruent conditions in a cluster including the rAI and extending into the frontal operculum and laterally to BA45 (S3; k=293, FWE corrected p=0.03, Peak: t=3.85 x=28, y=20, z=4), whereby those with lower and higher levels of neuroticism had the highest BOLD response in this region.

Effect of Neuroticism on Connectivity across the Sample

Using the same dorsal rAI seed described above, we observed a significant effect of group on connectivity between the seed and a cluster in portions of the left superior parietal lobule and precuneus associated with the dorsal attention network, with anterior extension into white matter (S4; k=695, FWE corrected p<0.001, Peak: t=3.89 x=−32, y=−20, z=30). This effect was driven by reduced connectivity to the incongruent compared to the congruent conditions in the HC compared to the MDD group. Finally, we observed a significant inverse curvilinear effect of neuroticism on connectivity during the incongruent compared to the congruent conditions between the dorsal rAI seed and a cluster in the lateral PFC localized in a region associated with the fronto-parietal control network (S4 k=278, FWE corrected p=0.04, Peak: t=−4.44 x=38, y=50, z=18), such that connectivity was highest for those in the middle range of the neuroticism scale.

Discussion

Adults with depression differ from one another regarding personality features, and these differences have consequences for the likelihood of success of particular treatments (11,12). In this study, we observed that depressed individuals with higher neuroticism had increased activity in the rAI and decreased activity in the left precuneus during an emotional Stroop task. The relationship between neuroticism and rAI activity was hypothesized, given findings linking neuroticism to activity in this region among HC (30–34,59), findings linking personality dysfunction to antidepressant treatment response (10–12), and findings linking antidepressant treatment response to activity in this region (38,60). Thus, this study provides convergent evidence for the importance of activity in the rAI for understanding clinically meaningful individual differences among those with MDD.

The anterior insula has been implicated in a wide variety of cognitive and emotional regulation processes and is believed to be a central component of the salience network (22,23). One set of theories (23,61) contends that the anterior insula, and particularly the dorsal anterior insula, is pivotal for adaptively switching between the default mode and central executive networks in order to appropriately process salient stimuli (22,62). One possible interpretation of the present findings is that those high in neuroticism may display altered salience processing during the presentation of emotional information. Poorly tuned salience detection could, in turn, result in faulty cortical network switching. This hypothesis is further supported by the results of exploratory functional connectivity analyses in which we observed reduced connectivity between the dorsal rAI and two regions (one in the lateral PFC, and one in the mid/posterior cingulate) associated with the fronto-parietal cognitive control network.

We did not hypothesize the negative relationship between neuroticism and activity in the precuneus. The ventral precuneus, in which the findings were localized, has been included as a key node of the default mode network (63,64). The negative observed relationship was due to increased activity to the congruent compared to incongruent condition, which could reflect deficits in the switch from default mode processing when responding to the congruent stimuli, the easier of the two conditions (35,65,66). This hypothesis fits well with the possibility that neuroticism may be associated with abnormalities in large-scale cortical network switching, however, these hypotheses require testing in future work with tasks designed specifically to examine these processes.

We did not observe the hypothesized relationship between neuroticism and activity in the sgACC. This stands in contrast to two prior sets of findings. Haas and colleagues (24) observed an association between neuroticism and activity in this region among healthy individuals. Webb and colleagues (67), using scalp recorded electroencephalogram (EEG) data collected at rest from the same parent study as the data reported herein, observed that increased resting EEG (gamma current density) signal localized to the sgACC was associated with increased neuroticism scores. Unlike the study by Haas and colleagues, we collected data on relatively few individuals from the middle of the neuroticism range. It is possible that the relationship is strongest over this portion of the range, and dissipates at the extremes. Indeed, in secondary analyses of BOLD response, we observed strong evidence of nonlinear relationships between neuroticism and neural response. Comparison to the findings by Webb and colleagues suggests that there may be a dissociation between task and rest states in the relationship between neuroticism and the functioning of the sgACC in MDD. Future work will need to examine this possibility as well as whether activity in this region to different kinds of emotional tasks might be associated with neuroticism.

In secondary analyses, we did not observe mean differences in behavioral performance or BOLD response between the MDD and HC groups. We did, however, observe reduced connectivity in the HC relative to the MDD groups between the dorsal rAI and regions associated with the dorsal attention network. Perhaps the most notable findings from the secondary analyses were the observations of curvilinear relationships between neuroticism and BOLD response in a rAI-frontal-opercular cluster and between neuroticism and measures of functional connectivity between the dorsal-rAI and lateral PFC. These findings suggest that the relationship between neuroticism and brain activity in and connectivity with the rAI may not be simple or linear. Notably, the present findings occur in the context of a broader literature that is quite mixed regarding the nature, location, and direction of MDD-HC differences in neural function (68–71). We contend that this variability may stem, in part, from the complex relationships between diagnostic status, neuroticism, and brain activity. Whether differences between MDD and HC groups are observed may depend on which parts of the neuroticism spectrum have been sampled in each group.

Many studies, like this one, adopt an extreme groups sampling approach to assess the neural correlates of important participant characteristics. Although such approaches have notable strengths, one limitation is that it can be difficult to ascertain the nature of the relationship between the construct in question and brain activity over the middle of the range. It will be important for future work regarding broad dimensions of psychological functioning, conducted in accordance with the Research Domain Criteria initiative (72), to sample across the range of possible scores on dimensional measures and to consider non-linear relationships with brain function. Additional limitations to the current study include the fact that the sample sizes from the MDD and HC groups were imbalanced, which could have affected power to detect between-group differences. Also, the shorter version of the NEO instruments was used to assess neuroticism. As such, it was not possible to calculate reliable subscales of neuroticism in order to examine which subscale(s) were driving the observed effects.

Conclusions

The current findings are among the first to link a clinical characteristic (personality dysfunction) with neural markers (functioning of the rAI) both of which have been associated with differential response to treatments for depression. This is an important next step for understanding the neural basis of clinically meaningful dimensions on which depressed patients differ, and it provides a target for future work to examine the mechanisms through which alterations in brain function affect treatment outcomes. Once these processes are better understood, it may be possible not only to better tailor existing treatments for specific individuals, but also to develop novel strategies that can more efficiently target an individual’s underlying pathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under award numbers U01MH092221 (Trivedi, M.H.) and U01MH092250 (McGrath, P.J., Parsey, R.V., Weissman, M.M.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was supported by the EMBARC National Coordinating Center at UT Southwestern Medical Center and the Data Center at Columbia University and Stony Brook University. Valeant Pharmaceuticals donated the Wellbutrin XL used in the EMBARC study.

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

APPENDIX

Financial Disclosures

Jay Fournier is supported by funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, K23-MH097889) and otherwise reports no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest. Amit Etkin has consulted for Otsuka Pharmaceuticals and received grant funding from Brain Resource, Inc. Jorge Almeida is supported by funding from the (1R25 MH101076) and otherwise reports no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest. Thilo Deckersbach’s research has been funded by NIH, NIMH, NARSAD, TSA, IOCDF, Tufts University, DBDAT and Otsuka Pharmaceuticals. He has received honoraria, consultation fees and/or royalties from the MGH Psychiatry Academy, BrainCells Inc., Clintara, LLC., Systems Research and Applications Corporation, Boston University, the Catalan Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Research, the National Association of Social Workers Massachusetts, the Massachusetts Medical Society, Tufts University, NIDA, NIMH, Oxford University Press, Guilford Press, and Rutledge. He has also participated in research funded by DARPA, NIH, NIMH, NIA, AHRQ, PCORI, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, The Forest Research Institute, Shire Development Inc., Medtronic, Cyberonics, Northstar, and Takeda. Marisa Toups has consulted for Otsuka pharmaceuticals and has received travel funds from Janssen Research and Development. Her research is supported by the NIMH and the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation. Benji Kurian has received research grant support from the following organizations: Targacept, Inc., Pfizer, Inc., Johnson & Johnson, Evotec, Rexahn, Naurex, Forest Pharmaceuticals and the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Melvin G. McInnis has served as a consultant for Janssen Pharmaceuticals. Maria A. Oquendo receives royalties from Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene for the commercial use of the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. Her family owns stock in Bristol Myers Squibb. Patrick J. McGrath has received research grant support from the Forest Research Laboratories, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, and Naurex. Maurizio Fava has received research support from: Abbot Laboratories; Alkermes, Inc.; American Cyanamid; Aspect Medical Systems; AstraZeneca; Avanir Pharmaceuticals; BioResearch; BrainCells Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb; CeNeRx BioPharma; Cephalon; Cerecor; Clintara, LLC; Covance; Covidien; Eli Lilly and Company; EnVivo Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Euthymics Bioscience, Inc.; Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Ganeden Biotech, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline; Harvard Clinical Research Institute; Hoffman-LaRoche; Icon Clinical Research; i3 Innovus/Ingenix; Janssen R&D, LLC; Jed Foundation; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development; Lichtwer Pharma GmbH; Lorex Pharmaceuticals; Lundbeck Inc.; MedAvante; Methylation Sciences Inc; National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia & Depression (NARSAD); National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM); National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA); National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH); Neuralstem, Inc.; Novartis AG; Organon Pharmaceuticals; PamLab, LLC.; Pfizer Inc.; Pharmacia-Upjohn; Pharmaceutical Research Associates., Inc.; Pharmavite® LLC; PharmoRx Therapeutics; Photothera; Reckitt Benckiser; Roche Pharmaceuticals; RCT Logic, LLC (formerly Clinical Trials Solutions, LLC); Sanofi-Aventis US LLC; Shire; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Stanley Medical Research Institute (SMRI); Synthelabo; Tal Medical; Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories. He has served on the advisory board or consulted for: Abbott Laboratories; Acadia; Affectis Pharmaceuticals AG; Alkermes, Inc.; Amarin Pharma Inc.; Aspect Medical Systems; AstraZeneca; Auspex Pharmaceuticals; Avanir Pharmaceuticals; AXSOME Therapeutics; Bayer AG; Best Practice Project Management, Inc.; Biogen; BioMarin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Biovail Corporation; BrainCells Inc; Bristol-Myers Squibb; CeNeRx BioPharma; Cephalon, Inc.; Cerecor; CNS Response, Inc.; Compellis Pharmaceuticals; Cypress Pharmaceutical, Inc.; DiagnoSearch Life Sciences (P) Ltd.; Dinippon Sumitomo Pharma Co. Inc.; Dov Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Edgemont Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eisai Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EnVivo Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; ePharmaSolutions; EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Euthymics Bioscience, Inc.; Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Forum Pharmaceuticals; GenOmind, LLC; GlaxoSmithKline; Grunenthal GmbH; i3 Innovus/Ingenis; Intracellular; Janssen Pharmaceutica; Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC; Knoll Pharmaceuticals Corp.; Labopharm Inc.; Lorex Pharmaceuticals; Lundbeck Inc.; MedAvante, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; MSI Methylation Sciences, Inc.; Naurex, Inc.; Nestle Health Sciences; Neuralstem, Inc.; Neuronetics, Inc.; NextWave Pharmaceuticals; Novartis AG; Nutrition 21; Orexigen Therapeutics, Inc.; Organon Pharmaceuticals; Osmotica; Otsuka Pharmaceuticals; Pamlab, LLC.; Pfizer Inc.; PharmaStar; Pharmavite® LLC.; PharmoRx Therapeutics; Precision Human Biolaboratory; Prexa Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; PPD; Puretech Ventures; PsychoGenics; Psylin Neurosciences, Inc.; RCT Logic, LLC ( formerly Clinical Trials Solutions, LLC); Rexahn Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Ridge Diagnostics, Inc.; Roche; Sanofi-Aventis US LLC.; Sepracor Inc.; Servier Laboratories; Schering-Plough Corporation; Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Somaxon Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Sunovion Pharmaceuticals; Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Synthelabo; Taisho Pharmaceutical; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited; Tal Medical, Inc.; Tetragenex Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; TransForm Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Transcept Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Vanda Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; VistaGen Therapeutics. He has received speaking or publishing fees from: Adamed, Co; Advanced Meeting Partners; American Psychiatric Association; American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology; AstraZeneca; Belvoir Media Group; Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH; Bristol-Myers Squibb; Cephalon, Inc.; CME Institute/Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; Forest Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; GlaxoSmithKline; Imedex, LLC; MGH Psychiatry Academy/Primedia; MGH Psychiatry Academy/Reed Elsevier; Novartis AG; Organon Pharmaceuticals; Pfizer Inc.; PharmaStar; United BioSource,Corp.; Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories. He has equity holdings in: Compellis; PsyBrain, Inc. He holds patents for Sequential Parallel Comparison Design (SPCD), licensed by MGH to Pharmaceutical Product Development, LLC (PPD); and patent application for a combination of Ketamine plus Scopolamine in Major Depressive Disorder (MDD), licensed by MGH to Biohaven. He holds copyrights for the MGH Cognitive & Physical Functioning Questionnaire (CPFQ), Sexual Functioning Inventory (SFI), Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ), Discontinuation-Emergent Signs & Symptoms (DESS), Symptoms of Depression Questionnaire (SDQ), and SAFER; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; Wolkers Kluwer; World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte.Ltd. Myrna Weissman received funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD), the Sackler Foundation, and the Templeton Foundation; and receives royalties from the Oxford University Press, Perseus Press, the American Psychiatric Association Press, and MultiHealth Systems. Madhukar H. Trivedi is or has been an advisor/consultant and received fee from: Abbott Laboratories, Inc., Abdi Ibrahim, Akzo (Organon Pharmaceuticals Inc.), Alkermes, AstraZeneca, Axon Advisors, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Cephalon, Inc., Cerecor, CME Institute of Physicians ,Concert Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Eli Lilly & Company, Evotec, Fabre Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Forest Pharmaceuticals, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen Global Services, LLC, Janssen Pharmaceutica Products, LP, Johnson & Johnson PRD, Libby, Lundbeck, Meade Johnson, MedAvante, Medtronic, Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Development America, Inc., Naurex, Neuronetics, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Pamlab, Parke-Davis Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Pfizer Inc., PgxHealth, Phoenix Marketing Solutions, Rexahn Pharmaceuticals, Ridge Diagnostics, Roche Products Ltd., Sepracor, SHIRE Development, Sierra, SK Life and Science, Sunovion, Takeda, Tal Medical/Puretech Venture, Targacept, Transcept, VantagePoint, Vivus, and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories. In addition, he has received grants/research support from: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), Cyberonics, Inc., National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Depression, National Institute of Mental Health and National Institute on Drug Abuse. Mary L. Phillips has received funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), including U01MH092221-01, and serves as a consultant to Roche Pharmaceuticals. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: Establishing Moderators and Biosignatures of Antidepressant Response for Clinical Care for Depression (EMBARC).

Identifier: NCT01407094.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Costa PT, McCrae RR. Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hengartner MP. The detrimental impact of maladaptive personality on public mental health: A challenge for psychiatric practice. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2015;6:717–7. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lahey BB. Public health significance of neuroticism. Am Psychol. 2009;64:241–256. doi: 10.1037/a0015309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fournier J, Tang TZ. Personality in depression. In: DeRubeis RJ, Strunk DR, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Mood disorders. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; In press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark LA. Temperament as a unifying basis for personality and psychopathology. J Abnorm Psychol. 2005;114:505–521. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotov R, Gamez W, Schmidt F, Watson D. Linking “big” personality traits to anxiety, depressive, and substance use disorders: A meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2010;136:768–821. doi: 10.1037/a0020327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krueger RF, Tackett JL. Personality and psychopathology: Working toward the bigger picture. J Personal Disord. 2003;17:109–128. doi: 10.1521/pedi.17.2.109.23986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watson D, Clark LA. Depression and the melancholic temperament. Eur J Pers. 1995;9:351–366. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bagby RM, Psych C, Quilty LC, Ryder AC. Personality and depression. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:14–25. doi: 10.1177/070674370805300104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon GE, Perlis RH. Personalized medicine for depression: Can we match patients with treatments? A J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1445–1455. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09111680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fournier JC, DeRubeis RJ, Shelton RC, Gallop R, Amsterdam JD, Hollon SD. Antidepressant medications v. cognitive therapy in people with depression with or without personality disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:124–129. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.037234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagby RM, Quilty LC, Segal ZV, McBride CC, Kennedy SH, Costa PT., Jr Personality and differential treatment response in major depression: A randomized controlled trial comparing cognitive-behavioural therapy and pharmacotherapy. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:361–370. doi: 10.1177/070674370805300605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hollon SD, Jarrett RB, Nierenberg AA, Thase ME, Trivedi M, Rush AJ. Psychotherapy and medication in the treatment of adult and geriatric depression: Which monotherapy or combined treatment? J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:455–468. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quilty LC, De Fruyt F, Rolland J-P, Kennedy SH, Rouillon PFdr, Bagby RM. Dimensional personality traits and treatment outcome in patients with major depressive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;108:241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang TZ, DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam J, Shelton R, Schalet B. Personality change during depression treatment: A placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:1322–1330. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maddux RE, Riso LP, Klein DN, Markowitz JC, Rothbaum BO, Arnow BA, et al. Select comorbid personality disorders and the treatment of chronic depression with nefazodone, targeted psychotherapy, or their combination. J Affect Disord. 2009;117:174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levenson JC, Wallace ML, Fournier JC, Rucci P, Frank E. The role of personality pathology in depression treatment outcome with psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:719–729. doi: 10.1037/a0029396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ormel J, Bastiaansen A, Riese H, Bos EH, Servaas M, Ellenbogen M, et al. The biological and psychological basis of neuroticism: Current status and future directions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eysenck HJ. The Biological Basis of Personality. Springfield, IL: Thomas; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Phillips ML, Ladouceur CD, Drevets WC. A neural model of voluntary and automatic emotion regulation: Implications for understanding the pathophysiology and neurodevelopment of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:833–857. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gyurak A, Gross JJ, Etkin A. Explicit and implicit emotion regulation: A dual-process framework. Cognition & Emotion. 2011;25:400–412. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.544160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Menon V, Uddin LQ. Saliency, switching, attention and control: A network model of insula function. Brain Struct Funct. 2010;214:655–667. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0262-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uddin LQ. Salience processing and insular cortical function and dysfunction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;16:55–61. doi: 10.1038/nrn3857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haas BW, Omura K, Constable RT, Canli T. Emotional conflict and neuroticism: Personality-dependent activation in the amygdala and subgenual anterior cingulate. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121:249–256. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.2.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wallace JF, Newman JP. Neuroticism and the attentional mediation of dysregulatory psychopathology. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1997;21:135–156. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wallace JF, Newman JP. Neuroticism and the facilitation of the automatic orienting of attention. Personality and Individual Differences. 1998;24:253–266. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bredemeier K, Berenbaum H, Most SB, Simons DJ. Links between neuroticism, emotional distress, and disengaging attention: Evidence from a single-target RSVP task. Cognition & Emotion. 2011;25:1510–1519. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2010.549460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pauli WM, Röder B. Emotional salience changes the focus of spatial attention. Brain Res. 2008;1214:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.03.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wyble B, Sharma D, Bowman H. Strategic regulation of cognitive control by emotional salience: A neural network model. Cognition & Emotion. 2008;22:1019–1051. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu CC, Samanez-Larkin GR, Katovich K, Knutson B. Affective traits link to reliable neural markers of incentive anticipation. Neuroimage. 2014;84:279–289. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stein MB, Simmons AN, Feinstein JS, Paulus MP. Increased amygdala and insula activation during emotion processing in anxiety-prone subjects. A J Psychiatry. 2007;164:318–327. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.2.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coen SJ, Kano M, Farmer AD, Kumari V, Giampietro V, Brammer M, et al. Neuroticism influences brain activity during the experience of visceral pain. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:909–917. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feinstein JS, Stein MB, Paulus MP. Anterior insula reactivity during certain decisions is associated with neuroticism. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2006;1:136–142. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsl016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paulus MP, Rogalsky C, Simmons A, Feinstein JS, Stein MB. Increased activation in the right insula during risk-taking decision making is related to harm avoidance and neuroticism. Neuroimage. 2003;19:1439–1448. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00251-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pizzagalli DA. Frontocingulate dysfunction in depression: Toward biomarkers of treatment response. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;36:183–206. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siegle GJ, Carter CS, Thase ME. Use of fMRI to predict recovery from unipolar depression with cognitive behavior therapy. A J Psychiatry. 2006;163:735–738. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siegle GJ, Thompson WK, Collier A, Berman SR, Feldmiller J, Thase ME, et al. Toward clinically useful neuroimaging in depression treatment: Prognostic utility of subgenual cingulate activity for determining depression outcome in cognitive therapy across studies, scanners, and patient characteristics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:913–924. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGrath CL, Kelley ME, Holtzheimer PE, Dunlop BW, Craighead WE, Franco AR, et al. Toward a neuroimaging treatment selection biomarker for major depressive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:821–829. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cromheeke S, Mueller SC. Probing emotional influences on cognitive control: an ALE meta-analysis of cognition emotion interactions. Brain Struct Funct. 2013;219:995–1008. doi: 10.1007/s00429-013-0549-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greenberg T, Chase HW, Almeida JR, Stiffler R, Zevallos CR, Aslam HA, et al. Moderation of the relationship between reward expectancy and prediction error-related ventral striatal reactivity by anhedonia in unmedicated major depressive disorder: Findings from the EMBARC study. A J Psychiatry. 2015;172:881–891. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14050594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trivedi MH, McGrath PJ, Fava M, Parsey RV, Kurian BT, Phillips ML, et al. Establishing moderators and biosignatures of antidepressant response in clinical care (EMBARC). Rationale and design. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;78:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition.(SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCrae RR, Costa PT. NEO Inventories: NEO Personality Inventory-3 (NEO -PI-3) Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uliaszek AA, Hauner KKY, Zinbarg RE, Craske MG, Mineka S, Griffith JW, et al. An examination of content overlap and disorder-specific predictions in the associations of neuroticism with anxiety and depression. J Res Pers. 2009;43:785–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamilton MA. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Watson D, Clark LA, Weber K, Assenheimer JS, Strauss ME, McCormick RA. Testing a tripartite model: II. Exploring the symptom structure of anxiety and depression in student, adult, and patient samples. J Abnorm Psychol. 1995;104:15–25. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watson D, Weber K, Assenheimer JS, Clark LA, Strauss ME, McCormick RA. Testing a tripartite model: I. Evaluating the convergent and discriminant validity of anxiety and depression symptom scales. J Abnorm Psychol. 1995;104:3–14. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Etkin A, Egner T, Peraza DM, Kandel ER, Hirsch J. Resolving emotional conflict: A role for the rostral anterior cingulate cortex in modulating activity in the amygdala. Neuron. 2006;51:871–882. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carter CS, Lesh TA, Barch DM. Thresholds, power, and sample sizes in clinical neruoimaging. Biological Psychiatry: Clinical Neuroscience and Neuroimaging. 2016;1:99–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McLaren DG, Ries ML, Xu G, Johnson SC. A generalized form of context-dependent psychophysiological interactions (gPPI). A comparison to standard approaches. Neuroimage. 2012;61:1277–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.03.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deen B, Pitskel NB, Pelphrey KA. Three systems of insular functional connectivity identified with cluster analysis. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:1498–1506. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cameron AC, Trivedi PK. Microeconometrics Using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bagby RM, Young LT, Schuller DR, Bindseil KD, et al. Bipolar disorder, unipolar depression and the Five-Factor Model of Personality. J Affect Disord. 1996;41:25–32. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(96)00060-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bianchi R, Laurent E. Depressive symptomatology should be systematically controlled for in neuroticism research. Neuroimage. 2016;125:1099–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.07.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Riese H, Ormel J, Aleman A, Servaas MN, Jeronimus BF. Don't throw the baby out with the bathwater: Depressive traits are part and parcel of neuroticism. Neuroimage. 2016;125:1103. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yeo BTT, Krienen FM, Sepulcre J, Sabuncu MR, Lashkari D, Hollinshead M, et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:1125–1165. doi: 10.1152/jn.00338.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Horwood LJ, Fergusson DM. Neuroticism, depression and life events: A structural equation model. Soc Psychiatry. 1986;21:63–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00578744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kornør H, Nordvik H. Five-factor model personality traits in opioid dependence. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park M, Hennig-Fast K, Bao Y, Carl P, Pöppel E, Welker L, et al. Personality traits modulate neural responses to emotions expressed in music. Brain Res. 2013;1523:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2013.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Conway CR, Chibnall JT, Gangwani S, Mintun MA, Price JL, Hershey T, et al. Pretreatment cerebral metabolic activity correlates with antidepressant efficacy of vagus nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant major depression: A potential marker for response? J Affect Disord. 2012;139:283–290. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sridharan D, Levitin DJ, Menon V. A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12569–12574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800005105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jilka SR, Scott G, Ham T, Pickering A, Bonnelle V, Braga RM, et al. Damage to the salience network and interactions with the default mode network. J Neurosci. 2014;34:10798–10807. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0518-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Raichle ME, Snyder AZ. A default mode of brain function: A brief history of an evolving idea. Neuroimage. 2007;37:1083–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sheline YI, Barch DM, Price JL, Rundle MM, Vaishnavi SN, Snyder AZ, et al. The default mode network and self-referential processes in depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:1942–1947. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812686106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hamilton JP, Furman DJ, Chang C, Thomason ME, Dennis E, Gotlib IH. Default-mode and task-positive network activity in major depressive disorder: Implications for adaptive and maladaptive rumination. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;70:327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Webb CA, Dillon DG, Pechtel P, Goer FK, Murray L, Huys QJ, et al. Neural correlates of three promising endophenotypes of depression: Evidence from the EMBARC study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;41:454–463. doi: 10.1038/npp.2015.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wagner G, Sinsel E, Sobanski T, Köhler S, Marinou V, Mentzel H-J, et al. Cortical inefficiency in patients with unipolar depression: An event-related FMRI study with the Stroop task. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:958–965. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.George MS, Ketter TA, Parekh PI, Rosinsky N, Ring HA, Pazzaglia PJ, et al. Blunted left cingulate activation in mood disorder subjects during a response interference task (the Stroop) J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9:55–63. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mitterschiffthaler MT, Williams SCR, Walsh ND, Cleare AJ, Donaldson C, Scott J, et al. Neural basis of the emotional Stroop interference effect in major depression. Psychol Med. 2008;38:247–256. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chechko N, Augustin M, Zvyagintsev M, Schneider F, Habel U, Kellermann T. Brain circuitries involved in emotional interference task in major depression disorder. J Affect Disord. 2013;149:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. A J Psychiatry. 2010;167:748–51. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.