Abstract

Study Design:

Retrospective study of registry data.

Objectives:

Aging of society and recent advances in surgical techniques and general anesthesia have increased the demand for spinal surgery in elderly patients. Many complications have been described in elderly patients, but a multicenter study of perioperative complications in spinal surgery in patients aged 80 years or older has not been reported. Therefore, the goal of the study was to analyze complications associated with spine surgery in patients aged 80 years or older with cervical, thoracic, or lumbar lesions.

Methods:

A multicenter study was performed in patients aged 80 years or older who underwent 262 spinal surgeries at 35 facilities. The frequency and severity of complications were examined for perioperative complications, including intraoperative and postoperative complications, and for major postoperative complications that were potentially life threatening, required reoperation in the perioperative period, or left a permanent injury.

Results:

Perioperative complications occurred in 75 of the 262 surgeries (29%) and 33 were major complications (13%). In multivariate logistic regression, age over 85 years (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.007, P = 0.025) and estimated blood loss ≥500 g (HR = 3.076, P = .004) were significantly associated with perioperative complications, and an operative time ≥180 min (HR = 2.78, P = .007) was significantly associated with major complications.

Conclusions:

Elderly patients aged 80 years or older with comorbidities are at higher risk for complications. Increased surgical invasion, and particularly a long operative time, can cause serious complications that may be life threatening. Therefore, careful decisions are required with regard to the surgical indication and procedure in elderly patients.

Keywords: elderly, complications, spine surgery, risk factor

Introduction

Aging of society and recent advances in surgical techniques and general anesthesia have increased the demand for spinal surgery in elderly patients. However, many perioperative complications occur in these patients. Some studies have indicated a concern of increased morbidity and have cautioned against spinal surgery in the elderly,1-5 whereas others have reported low complication rates in this population and provided support for spinal surgery.6-8 In general, the term “elderly” is accepted to mean age ≥65 years,9-11 but with rapid aging of society, extremely elderly patients aged over 80 years now undergo spinal surgery,12-15 mostly for lumbar lesions. However, a multicenter study of perioperative complications has not been reported in such patients, including those with cervical, thoracic, and lumbar lesions.

Complications range from mild to severe, and many are resolved by appropriate treatment without leaving sequelae, but some are life threatening, Thus, in this study, we classified complications as those that required reoperation or left permanent injury as major complications, and all perioperative complications, including those that did not significantly alter the course of treatment, as minor complications. All perioperative complications in all lesions for patients older than 80 years were identified through a retrospective review of a multicenter database. The frequency and severity of complications were analyzed and the risk for complications was examined using patient-specific and surgical factors.

Methods

Demographic Data

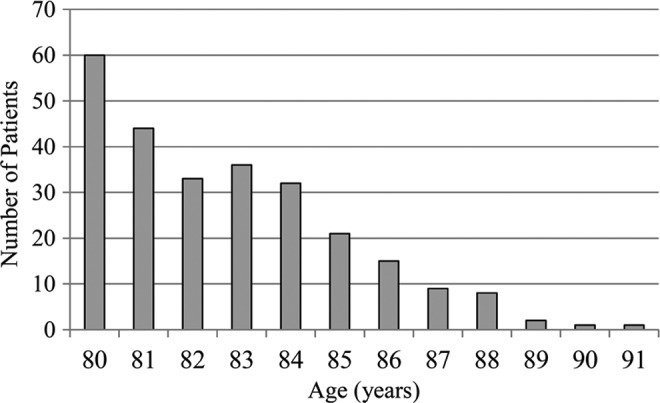

The study was performed by JASA (Japan Association of Spine Surgeons with Ambition) using a retrospective analysis of patients aged ≥80 years treated with spinal surgery at 35 facilities in 2014. The surgery data was included for the period from January 2010 to December 2013. A total of 262 such patients were identified, including 122 males and 140 females. The characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. Age ranged from 80 to 91 years, with a mean of 83 years (Figure 1). Lesions were cervical in 74 patients (28%), thoracic in 13 (5%), and lumbar in 175 (67%) (Table 2). Diagnoses included lumbar spinal canal stenosis (LSCS) due to spondylosis in 132 patients, cervical spondylotic myelopathy in 56, LSCS due to spondylolisthesis in 21, thoracic-lumbar compression fracture in 19, cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) in 6, pyogenic spondylitis in 5, and others in 23 (Table 2). The average length of hospital stay (LOS) was 38 ± 19 days. The mean operative time was 171 minutes, mean estimated blood loss (EBL) was 289 mL, and 87 patients underwent fusion surgeries with instrumentation (Table 1). The institutional review board approved the study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 262 Cases.

| Item | Value (Range) |

|---|---|

| Demographic | |

| Age (years) | 83 (80-91) |

| Sex, male/female (n/n) | 122/140 |

| Previous spinal surgery (n) | 47 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.3 (14-33) |

| Disease duration (years) | 3.6 (0.1-55) |

| Smoking status (n) | 4 |

| Drug use | |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) | 122 |

| Opioids | 18 |

| Osteoporosis agents | 68 |

| Anticoagulants | 58 |

| Comorbidity | |

| Hypertension | 107 |

| Preexisting neoplasm | 45 |

| Diabetes | 40 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 20 |

| Operative factor | |

| Operative time (minutes) | 171 (34-615) |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 289 (5-6500) |

| Fusion with instrumentation (n) | 87 |

Figure 1.

Bar graph showing the population stratified by age.

Table 2.

Diseases and Lesions in 262 Cases.

| Disease and surgical lesion | n (%) |

|---|---|

| LSCS (lumbar spondylosis) | 132 (50) |

| Cervical spondylotic myelopathy | 56 (21) |

| LSCS (spondylolisthesis) | 21 (8) |

| Thoracic-lumbar compression fracture | 19 (75) |

| Cervical OPLL | 6 (2) |

| Pyogenic spondylitis | 5 (2) |

| Others | 23 (9) |

| Cervical | 74 (28) |

| Thoracic | 13 (5) |

| Lumbar | 175 (67) |

Abbreviations: LSCS, lumbar spinal canal stenosis; OPLL, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament.

Definitions of Risk Factors and Medical Comorbidities

The risk for postoperative complications was examined by comparing background factors in patients with and without complications using univariate and multivariate analysis. These factors included age, gender, previous spinal surgery (resurgery at the same index level), body mass index (BMI), disease duration, smoking status, drug use (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], opioids, osteoporosis agents, and anticoagulants), comorbidities (hypertension, preexisting neoplasm, diabetes, and cerebrovascular disease), and operative factors (operative time, EBL, and fusion with instrumentation).

Outcome Variables

Two types of complications were defined—those related to surgery and all postoperative major and minor complications, which were collectively defined as perioperative complications; and postoperative major complications only. Major complications were defined as those that were potentially life threatening, required reoperation in the perioperative period, or left a permanent injury. These included cardiac, urinary, renal, and wound-related complications, and hemorrhage or hematoma complicating a procedure. Minor complications were those events that required additional intervention, but did not significantly alter the course of treatment.16 A simple questionnaire was given to all patients after hospital discharge to examine patient satisfaction after surgery, using a 5-point scale: 1 = not satisfied at all, 2 = not much satisfaction, 3 = neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 4 = some satisfaction, and 5 = major satisfaction.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic variables. Differences between 2 groups were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test or Student’s t test, and those between 3 groups by Kruskal-Wallis test. A multivariable logistic regression model was constructed for multivariate analysis using variables with P < .05 in univariate analysis. Multivariate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22 for Windows (IBM, Armonk, NY). P < .05 was considered to be significant in all analyses.

Results

Perioperative complications, including major and minor complications, occurred in 75 of the 262 cases (29%). These included 16 intraoperative and 59 postoperative complications. The 5 common perioperative complication were delirium, screw malposition, epidural hemorrhage, surgical site infection (SSI), and urinary infection (Table 3). There were 33 major complications (13%) that were potentially life threatening, required reoperation, or required an extended hospitalization period, with the 3 most common being epidural hemorrhage, SSI, and urinary infection (Table 3). There was no perioperative mortality. The rates of complications for cervical and thoracic lesion were higher than that for lumbar lesions, but the incidence for each lesion did not differ significantly (Table 4). All complications occurred during the period of initial hospitalization, and there were no readmission cases. The LOSs were 36 ± 19 days without complication, 38 ± 20 days with complication, and 48 ± 17 days with major complication, with a significant difference between the patients with major complications compared with the other 2 groups (P < .01). For patient satisfaction after surgery, the rates of scores 4 or 5 (indicating satisfaction) were 55% (41/75) in the complication group and 89% (166/187) in the no complication group, with a significant difference between these groups (P < .01).

Table 3.

Details of Perioperative Complications (n = 75) and Major Complications (n = 33).

| Complication | No. of Cases |

|---|---|

| Intraoperative complication (n = 16) | |

| Screw malposition | 8 |

| Dural tear | 5 |

| Root injury | 2 |

| Peritoneal injury | 1 |

| Postoperative complication (n = 59) | |

| Delirium | 15 |

| Epidural hemorrhagea | 7 |

| Surgical site infectiona | 7 |

| Urinary infectiona | 6 |

| Cerebral infarctiona | 3 |

| Transient muscle weakness | 3 |

| Renal dysfunctiona | 2 |

| C5 palsy | 2 |

| Systemic edemaa | 2 |

| Liver dysfunctiona | 2 |

| Respiration disordera | 2 |

| Acute myocardial infarctiona | 1 |

| Drug rash | 1 |

| Arrhythmia | 1 |

| Anginaa | 1 |

| Hypotension | 1 |

| Infected with flu virus | 1 |

| Crural neuralgia | 1 |

| Adjacent vertebral fracture | 1 |

aIndicates a major complication (n=33).

Table 4.

Relationships Between Surgical Lesions and Complications.

| Surgical Lesion | Perioperative Complications (n = 75) | Major Complications (n = 33) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | Rate (%) | P | Patients | Rate (%) | P | |

| Cervical | 24 | 35 | n.s. | 12 | 17 | n.s. |

| Thoracic | 6 | 43 | 2 | 14 | ||

| Lumbar | 45 | 25 | 19 | 11 | ||

Abbreviation: n.s., not significant.

The results of univariate and multivariate analyses are shown in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. In univariate analysis, age >85 years (P = .027), cerebrovascular disease (P = .018), longer operation time (P = .046), and greater EBL ≥500 g (P = .001) were significantly related to all perioperative complications (Table 5); and anticoagulant use (P = .028), diabetes (P = .026), and operative time >180 minutes (P = .015) were significantly related to major complications (Table 5). In multivariate logistic regression, age >85 years (HR = 1.007, 95% CI = 1.001-1.009; P = .025) and EBL ≥500 g (HR = 3.076, 95% CI = 1.425-6.641; P = .004) were significantly associated with perioperative complications; and operative time >180 minutes (HR = 2.78, 95% CI = 1.317-5.917; P = .007) was significantly associated with major complications (Table 6).

Table 5.

Univariate Analysis of Risk for Perioperative and Major Complication (n = 75).

| Perioperative Complication (n = 75) | Major Complication (n = 33) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P |

| Demographic | ||||

| >85 years of age | 1.159 (1.017-1.320) | .027a | 1.153 (0.974-1.366) | .099 |

| Female | 0.848 (0.428-1.679) | .636 | 0.783 (0.316-1.939) | .597 |

| Previous spinal surgery | 0.913 (0.397-2.096) | .829 | 0.942 (0.324-2.736) | .912 |

| Body mass index | 1.006 (0.946-1.070) | .854 | 0.952 (0.883-1.026) | .198 |

| Disease duration | 1.008 (0.945-1.074) | .816 | 0.991 (0.892-1.100) | .858 |

| Smoking status | 0.624 (0.048-8.113) | .719 | 0.345 (0.019-6.271) | .472 |

| Drug use | ||||

| NSAIDs | 0.732 (0.384-1.396) | .343 | 0.662 (0.281-1.560) | .345 |

| Opioids | 0.852 (0.233-3.116) | .808 | 0.283 (0.069-1159) | .079 |

| Osteoporosis agents | 0.553 (0.258-1.183) | .127 | 0.956 (0.358-2.551) | .928 |

| Anti-coagulants | 2.138 (0.910-5.020) | .081 | 4.338 (1.173-16.035) | .028a |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Hypertension | 1.025 (0.540-1.948) | .939 | 1.028 (0.437-2.421) | .950 |

| Preexisting neoplasm | 0.605 (0.270-1.354) | .221 | 0.545 (0.192-1.548) | .254 |

| Diabetes | 0.463 (0.198-1.082) | .076 | 3.246 (1.149-9.174) | .026a |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 0.258 (0.084-1.082) | .018a | 0.334 (0.086-1.299) | .113 |

| Intraoperative factor | ||||

| Operative time (≥180 min) | 1.005 (1.000-1.009) | .046a | 4.329 (1.329-14.08) | .015a |

| Estimated blood loss (≥500 g) | 5.029 (2.438-10.18) | .001a | 1.599 (0.642-3.982) | .313 |

| Use instrumentation | 0.783 (0.355-1.725) | .544 | 0.397 (0.128-1.001) | .109 |

Abbreviations: HR, hazard ratio; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

aIndicates significant difference (P < .05).

Table 6.

Multivariate Analysis of Risk for Perioperative and Major Complication (n = 33).

| Perioperative Complication (n = 75) | Major Complication (n = 33) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR (95% CI) | P | HR (95% CI) | P |

| Demographic | ||||

| >85 years of age | 1.007 (1.001-1.009) | .025a | ||

| Intraoperative factor | ||||

| Operative time (≥180 min) | 2.780 (1.317-5.917) | .007a | ||

| Estimated blood loss (≥500 g) | 3.076 (1.425-6.641) | .004a | ||

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

aIndicates significant difference (P < .05).

Discussion

Demographic data indicates that there are 9.3 million people in Japan who are more than 80 years old, equivalent to 7.3% of the total population, and this cohort is projected to increase to 14.5% by 2035.17 In ultra-aging countries, the demand for spinal surgery in elderly patients has grown in recent years.14,15

Complications in lumbar surgeries for patients over 65 years of age have been reported to occur at rates of 3% to 29%,1,2,4,6,18-21 and older age, comorbidities, blood loss, operative time, and number of levels increase the rate of complications.1,3,15,22 For patients over 80 years of age, 2 studies of lumbar surgeries have found complication rates of 20% with a relationship with length of intensive care unit stay.23 In 26% of lumbar decompression cases in patients aged over 80 years, a general state of mental confusion was observed after surgery for several days, but was fully reversible, and there was no permanent morbidity or perioperative death.24 These studies focused on lumbar surgeries, and there has been no multicenter study in extremely elderly patients after cervical and thoracic surgeries. In our series with all lesions, the rates were 29% for perioperative complications and 13% for major complications, similar to previous reports of lumbar surgeries. In a Japanese multicenter study, Yone at al8 found a complication rate of 10.4% in patients with a mean age of 59.3 years in more than 30 000 spinal surgeries. In comparison, extremely elderly patients over 80 years are at higher risk for complications, with the rate increased by 2.7 times compared with patients of all ages. In our series, this could be a reason for the relatively low patient satisfaction postoperatively.

We classified complications into minor and major events. Minor perioperative complications were included because it is important for doctors to recognize all adverse events after surgery to avoid more serious problems in the postoperative course and prevent major complications. This is likely to lead to an improved outcome and patient satisfaction. Major complications were defined as those that were potentially life threatening, required reoperation in the perioperative period or left a permanent injury. Perioperative death was also included, but there were no such cases in our series. Among postoperative complications, delirium was the most common, and had features of acute onset and a fluctuating course, inattention, and disorganized thinking in our series. Postoperative delirium is common in extremely elderly patients and is associated with a significant increase in mortality, complications, length of hospital stay, and admission to a long-term care facility.25 In patients older than 70 years, 20% may develop postoperative delirium.26 Cerebrovascular disease was also a significant perioperative complication, and it has been reported that this condition has a strong association with postoperative delirium.27

Risk factors for perioperative complications were age >85 years (HR = 1.007) and EBL ≥500 g (HR = 3.076), and that for major complications was operative time ≥180 minutes (HR = 2.78). Surgical invasion such as operative time and EBL have previously been shown to be significant risk factors,4,5,11,26 but HRs were not determined. Thus, to prevent these complications, care is required regarding the surgical extent, indication, and procedure, including the invasiveness of surgery, such as use of instrumentation. If instrumentation is used, the fixation range should be carefully determined in extremely elderly patients.

This study has the limitation of a retrospective design based on data review, which did not allow evaluation of preoperative severity and detailed evaluation of postoperative course. Despite this limitation, the results provide important estimates of inpatient morbidity and mortality after spinal surgery in extremely elderly patients.

Conclusions

Perioperative and major complications after spine surgery in the extremely elderly occurred at rates of 29% and 13%, respectively, in our patients. Increased surgical invasion, and especially an operative time of more than 3 hours, was a strong risk factor for potentially life-threatening complications. Therefore, for extremely elderly patients, particular care is required in the choice of the surgical procedure.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Carreon LY, Puno RM, Dimar JR, 2nd, Glassman SD, Johnson JR. Perioperative complications of posterior lumbar decompression and arthrodesis in older adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:2089–2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Loeser JD, Bigos SJ, Ciol MA. Morbidity and mortality in association with operations on the lumbar spine. The influence of age, diagnosis, and procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:536–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Imagama S, Kawakami N, Tsuji T, et al. Perioperative complications and adverse events after lumbar spinal surgery: evaluation of 1012 operations at a single center. J Orthop Sci. 2011;16:510–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Katz JN, Lipson SJ, Larson MG, McInnes JM, Fossel AH, Liang MH. The outcome of decompressive laminectomy for degenerative lumbar stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:809–816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee MJ, Konodi MA, Cizik AM, et al. Risk factors for medical complication after cervical spine surgery: a multivariate analysis of 582 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38:223–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Best NM, Sasso RC. Outpatient lumbar spine decompression in 233 patients 65 years of age or older. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:1135–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rosen DS, O’Toole JE, Eichholz KM, et al. Minimally invasive lumbar spinal decompression in the elderly: outcomes of 50 patients aged 75 years and older. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:503–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yone K, Imajo Y, Iguchi T, et al. Nationwide survey on complications of spine surgery in Japan. J Spine Res. 2013;4:462. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gorman M. Development and the rights of older people In: Randel J, German T, Ewing D. eds. The Ageing and Development Report: Poverty, Independence and the World’s Older People. London, England: Earthscan; 1999:3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roebuck J. When does “old age” begin? The evolution of the English definition. J Soc History. 1979;12:416–428. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Thane P. History and the sociology of ageing. Soc History Med. 1989;2:93–96. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bydon M, Abt NB, De la Garza-Ramos R, et al. Impact of age on short-term outcomes after lumbar fusion: an analysis of 1395 patients stratified by decade cohorts. Neurosurgery. 2015;77:347–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li G, Patil CG, Lad SP, Ho C, Tian W, Boakye M. Effects of age and comorbidities on complication rates and adverse outcomes after lumbar laminectomy in elderly patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2008;33:1250–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sciubba DM, Scheer JK, Yurter A, et al. Patients with spinal deformity over the age of 75: a retrospective analysis of operative versus non-operative management. The International Spine Study Group (ISSG). Eur Spine J. 2016;25:2433–2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang MY, Green BA, Shah S, Vanni S, Levi AD. Complications associated with lumbar stenosis surgery in patients older than 75 years of age. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;14:e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Glassman SD, Alegre G, Carreon L, Dimar JR, Johnson JR. Perioperative complications of lumbar instrumentation and fusion in patients with diabetes mellitus. Spine J. 2003;3:496–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Statistics Bureau. The 64th Japan Statistical Yearbook. Tokyo, Japan: Statistics Bureau; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Benz RJ, Ibrahim ZG, Afshar P, Garfin SR. Predicting complications in elderly patients undergoing lumbar decompression. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;384:116–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Johnsson KE, Rosén I, Udén A. The natural course of lumbar spinal stenosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;279:82–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Quigley MR, Kortyna R, Goodwin C, Maroon JC. Lumbar surgery in the elderly. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:672–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Smith EB, Hanigan WC. Surgical results and complications in elderly patients with benign lesions of the spinal canal. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:867–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cassinelli EH, Eubanks J, Vogt M, Furey C, Yoo J, Bohlman HH. Risk factors for the development of perioperative complications in elderly patients undergoing lumbar decompression and arthrodesis for spinal stenosis: an analysis of 166 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:230–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Raffo CS, Lauerman WC. Predicting morbidity and mortality of lumbar spine arthrodesis in patients in their ninth decade. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Galiano K, Obwegeser AA, Gabl MV, Bauer R, Twerdy K. Long-term outcome of laminectomy for spinal stenosis in octogenarians. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:332–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mouchoux C, Rippert P, Duclos A, et al. Impact of a multifaceted program to prevent postoperative delirium in the elderly: the CONFUCIUS stepped wedge protocol. BMC Geriatr. 2011;11:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kratz T, Heinrich M, Schlauß E, Diefenbacher A. Preventing postoperative delirium. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:289–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gosselt AN, Slooter AJ, Boere PR, Zaal IJ. Risk factors for delirium after on-pump cardiac surgery: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2015;19:346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]