Abstract

The vascular basement membrane contributes to the integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which is formed by brain capillary endothelial cells (BCECs). The BCECs receive support from pericytes embedded in the vascular basement membrane and from astrocyte endfeet. The vascular basement membrane forms a three-dimensional protein network predominantly composed of laminin, collagen IV, nidogen, and heparan sulfate proteoglycans that mutually support interactions between BCECs, pericytes, and astrocytes. Major changes in the molecular composition of the vascular basement membrane are observed in acute and chronic neuropathological settings. In the present review, we cover the significance of the vascular basement membrane in the healthy and pathological brain. In stroke, loss of BBB integrity is accompanied by upregulation of proteolytic enzymes and degradation of vascular basement membrane proteins. There is yet no causal relationship between expression or activity of matrix proteases and the degradation of vascular matrix proteins in vivo. In Alzheimer’s disease, changes in the vascular basement membrane include accumulation of Aβ, composite changes, and thickening. The physical properties of the vascular basement membrane carry the potential of obstructing drug delivery to the brain, e.g. thickening of the basement membrane can affect drug delivery to the brain, especially the delivery of nanoparticles.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, the brain’s vascular basement membrane, blood-brain barrier, drug delivery

Introduction

Basement membranes are layers of complex extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins that provide support for epithelial and endothelial cells, hence separating these from the underlying tissue.1 In the central nervous system (CNS), the vascular basement membrane separates the endothelial cells from neurons and glial cells and contributes to vessel development and formation and maintenance of the blood-brain barrier (BBB).2,3 The BBB is formed by thin non-fenestrated brain capillary endothelial cells (BCECs) sealed together by tight junctions that protect the CNS by limiting the passage of, e.g., naturally occurring molecules, microbiological pathogens, and the majority of administered pharmaceuticals circulating in the blood.3–5 The restrictive function of the BCECs is sustained by pericytes embedded in the vascular basement membrane and astrocyte endfeet.3,6,7 Together BCECs, pericytes, and astrocytes synthesize and deposit proteins extracellularly thereby forming the vascular basement membrane.8–11

The vascular basement membrane denotes together with the interstitial matrix and the perineuronal network of the additional brain parenchyma the brain’s ECM (Table 1). The vascular basement membrane has a thickness of 20–200 nm and consists of a three-dimensional network predominantly composed of proteins from four major glycoprotein families, i.e. laminins, collagen IV isoforms, nidogens, and heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG).12,13 Additionally, many other proteins are differentially expressed in the vascular basement membrane depending on the developmental and physiological state,14 these include insoluble fibronectin, fibulin 1 and 2, collagen type XVIII, thrombospondins 1, and SPARC (secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine) (Table 1).15–19 The interstitial matrix of the brain parenchyma differs from the vascular basement membrane in that it forms a dense network of glycoproteins and proteoglycans like tenascins, chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs), and hyaluronan.20,21 Similarly, the perineuronal network that surrounds neurons differs from the vascular basement membrane by forming a densely organized network composed of high concentrations of CSPGs, tenascin-R, and link proteins.21

Table 1.

Overview of the composition of the extracellular matrix in the brain.

| Components of the vascular basement membrane | Components of the brain parenchyma (interstitial matrix and the perineuronal nets) |

|---|---|

| Collagen Collagen IV [α1(IV)]2α2(IV)18,167,168 | |

| Laminin isoforms (dependent on vessel type see Figure 2) • Laminin 11134 • Laminin 2111,6,9 • Laminin 4118,10, 42110,43 • Laminin 51110,43 | |

| Nidogens • Nidogen-136,49,51,170 • Nidogen-28,50 | |

| Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) • Perlecan8,171 • Agrin8,75,172 • Collagen XVIII8,14,19 | Chondroitin sulfate/dermatan sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs, DSPGs) • Biglycan173 • Decorin174 • Phosphacan175 • Neuron-glial antigen 2 (NG2)176,177 • Aggrecan169 • Brevican (BEHAB)178,179 • Neurocan180 • Versican177,181,182 |

| Fibronectin (primarily development and pathology)8,16,167,183 | |

| Other glycoproteins • Thrombospondin-117 • Fibulin-18,15 • Fibulin-215 (larger blood-vessels) • SPARC8,18,36 | Other glycoproteins • Link protein184 • Reelin185 • Tenascin-C186 • Tenascin-R187 |

Structurally, the vascular basement membrane consists of two principally different entities, i.e. the endothelial and parenchymal basement membranes, both of main importance for maintaining the integration of BCECs with pericytes and astrocytes.10,14,22 These three cell types adhere to the basement membrane by specific members of the integrin or dystroglycan receptor families, thereby maintaining the cells in position and adding to the mechanic-physical properties of the BBB.12,23 Dystroglycan consists of a highly glycosylated extracellular α-subunit and a transmembrane β-subunit. The α-dystroglycan form is responsible for the linkage to the basement membrane proteins whereas β-dystroglycan links α-dystroglycan to the actin cytoskeleton.24 In the adult mouse brain, the expression of dystroglycan is found in endothelial cells and perivascular astrocytes and their endfeet.25 Integrins are heterodimer transmembrane glycoproteins consisting of α- and β-chains, which bind to many proteins of the vascular basement membrane and activate several signalling pathways.26 Different integrin isoforms are involved in the binding of the BCECs, pericytes, and astrocytes to the vascular basement membrane. Particularly different β1-integrins are reported to be expressed by BCECs (α1β1, α3β, α6β1, and αvβ1),23,27–29 pericytes (α4β1),30 and astrocytes (α1β1, α5β1, α6β1).28 The interaction of endothelial β1-integrins with collagen IV of the basement membrane is correlated to expression of the tight junction protein claudin-5 and to the BBB integrity in vitro.31 Thus the interaction through the integrin receptors both provide physical support and regulate signalling pathways, whereby the BCECs can adapt to changes in the microenvironment.23

Among many important functions of the vascular basement membrane, it displays high capacity for binding of molecules like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (Table 2).14,32 It is also recognized as the major route that soluble molecules and fluids need to transverse when entering or leaving the brain.2 Furthermore, the parenchymal basement membrane functions as a physical barrier to infiltrating leukocytes.33,34

Table 2.

Soluble factors found in the vascular basement membrane in the brain.

| Heparin-binding factors: |

| Basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF)32,188 |

| Transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β)189 |

| Glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF)190 |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)191,192 |

| Heparin-binding epidermal growth factor (HE-EGF)193 |

| Neurogulin-1194 |

| Perlecan core protein binding factors: |

| Platelet derived growth factor beta (PDGFβ)7,42,56 |

Major changes in the molecular composition of the vascular basement membrane can be observed in acute and chronic neuropathological settings,35–38 which probably add significantly to disease pathogenesis. In the present review, we cover the molecular composition of the vascular basement membrane, how this basement membrane is affected in stroke and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), and how physical properties of the basement membrane ultimately can act as a second barrier beyond the BBB, thus potentially obstructing drug delivery to the brain.

Molecular composition of the vascular basement membrane

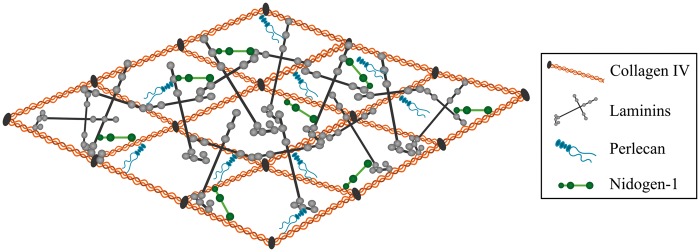

The assembly of the vascular basement membrane is dependent on an initial self-assembly of laminin into a sheet followed by binding to nidogen and HSPGs. To complete the formation of the vascular basement membrane, nidogen and HSPGs are linked to collagen IV, hence allowing the latter to form a secondary stabilizing polymer network (Figure 1).39,40 Laminins are cross-shaped and the most abundant non-collagenous basement membrane protein. The different laminins all consist of an α-chain, a β-chain, and a γ-chain. Five α, four β, and three γ chains exist and can combine to form 16 different laminin isoforms.34,41 The biological role of the laminins is largely defined through their α-chain interaction with integrins expressed by BCECs, pericytes, and astrocytes.34,42 The laminins of the vascular basement membrane consist of either α1, α2, α4, or α5 in combination with β1 and γ1 chains resulting in a composition of the laminin isoforms 111, 211, 411, and 511.14 Additionally, laminin 421 is also present along the cerebral vasculature.8,18,43 The laminin self-assembly results in the formation of polymers. This polymerization is a two-way process with an initial temerature-dependent step followed by a calcium-dependent step. Calcium is thus crucial for the polymerization of laminin.44

Figure 1.

Illustration showing the architecture of the vascular basement membrane. The basement membrane is composed of different extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, with the majorities being collagen IV, various laminin isoforms, perlecan, and nidogen-1. Laminin and collagen IV can self-assemble into 3D networks that are interconnected by nidogen and perlecan. Adopted from Hallmann et al.14

Collagen IV consists of polypeptide chains derived from six different α chains, which can combine and form three different collagen IV isoforms. The collagen IV isoform predominantly expressed in the brain consists of two α1 and one α2 chain that fuse to form the collagen IV [α1(IV)]2α2(IV) isoforms.1,44–46 Inside cells, the three α-chains assemble forming triple helical molecules, termed protomers, which oligomerize outside the cells into a supramolecular network.47 The self-assembly of the collagen IV protomers is associated with both lateral (side-by-side) as well as C- and N-terminal non-covalent bindings of the collagen IV monomers.48 The assembly of the collagen IV network outside the cells is dependent on chloride, which facilitates the modulation of salt bridge interaction within the trimeric non-collagenous 1 domain of the C-terminal.47

The laminin and collagen IV networks are held together by nidogen.44 Two isoforms of nidogen, nidogen-1 and -2 (entactin-1 and -2), have been identified and consist of three globes (G1, G2, G3) connected by segments of variable lengths. G1 and G2 are located within the N-terminus and G3 at the C-terminus.49,50 Nidogen-1 is important for connecting and stabilizing the self-assembled layers of laminin and collagen IV.49,51 In addition to laminin and collagen IV, nidogen-1 also binds fibulin and perlecan.52,53 Nidogen-2 is also able to bind basement membrane components. However, the mRNA expression of nidogen-2 is significantly downregulated already at early postnatal age, implying its significance during embryogenesis.50

Three different HSPGs, perlecan, agrin, and collagen XVII, are found within the vascular basement membrane with agrin and perlecan being the most abundant.54 Perlecan has a multi-domain protein core with three glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains at its N-terminus. It is integrated into the collagen IV/laminin network and plays an important role in the maintenance of basement membrane integrity and binding of growth factors.55,56 There are several spliced isoforms of agrin (i.e. z+ and z0), each with different functions. The isotype of agrin present in the vascular basement membrane is referred to as z0, as this form is devoid of an amino acid insertion at the COOH terminal.57,58 The HSPGs are able to tether and accumulate growth factors to protect them from degradation and modulate paracrine signalling of surrounding cells.59,60 Some of the heparin-binding and perlecan core protein binding factors found within the vascular basement membrane are listed in Table 2.

Cellular contribution to the basement membrane along the vascular tree

The distinct types of vessels denoting the cerebral vascular tree, i.e. major arteries penetrating the pial surface, arterioles, capillaries, postcapillary venules, venules, and veins, mutually vary in terms of vascular wall thickness and composition of basement membrane proteins. Especially, the distribution of various laminin isoforms along the brain vasculature has received much attention.10,14,34

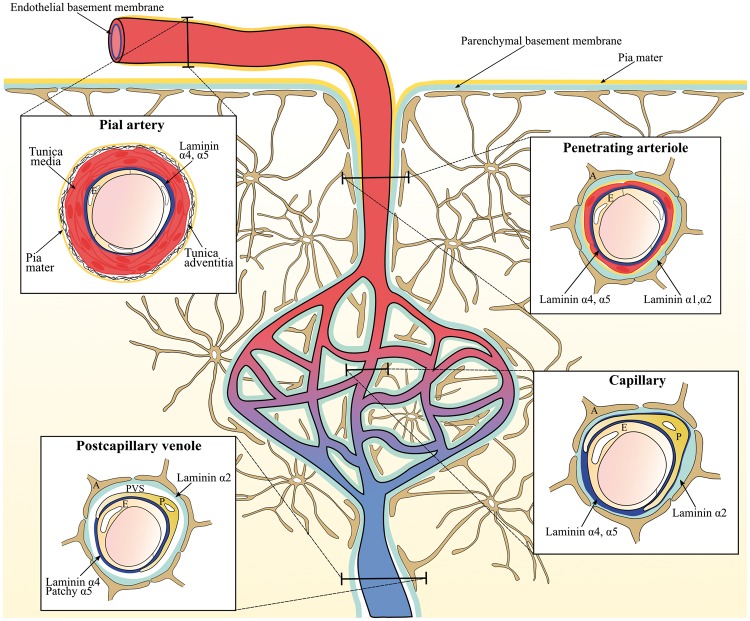

Pial arteries consist of a monolayer of endothelial cells and its basement membrane surrounded by smooth muscle cells (tunica media), connective tissue (tunica adventitia), and a coverage of pial cells. The pial arteries penetrate the brain parenchyma and subsequently branch into smaller arterioles surrounded by the pial cells with their underlying basement membrane, the astroglial basement membrane, and astrocyte endfeet. Together the pial and astroglial basement membrane is referred to as the parenchymal basement membrane (Figure 2).61,62 Thus, in the large parenchymal arteries and arterioles, the vascular basement membrane consists of two principally different entities, i.e. the endothelial and parenchymal basement membranes distinguished by their distribution of laminin isoforms. The endothelial basement membrane contains the laminin isoforms 411 and 511 derived from endothelial cells, whereas the parenchymal basement membrane of the penetrating arteries and arterioles contains laminin isoforms 111 and 211 derived from pial cells and astrocytes, respectively (Figure 2).10,34 Laminin 411 is unequivocally expressed in the endothelial basement membrane independent of vessel type. Oppositely, the expression of laminin 511 is correlated to both vessel maturation and type.8,34

Figure 2.

The differential expression of laminins along the cerebrovascular tree. The illustration shows the lining of the parenchymal (light blue) and endothelial basement membrane (dark blue) along the cerebrovascular tree with a cross section of the pial vessel, penetrating arteriole, capillary, and postcapillary venule. Laminin α1 and α2 are expressed by pial cells of the pia mater (yellow line) and astrocytes, respectively, and these can be found in the parenchymal basement membrane of the penetrating arterioles. As the contribution from the pial cells diminishes, the parenchymal basement membrane of the capillaries and postcapillary venules no longer has laminin α1. Laminin α4 is uniformly expressed in the endothelial basement membrane along the cerebrovascular tree. Oppositely, laminin α5 is expressed in the endothelial basement membrane of the pial vessel, penetrating arterioles, and capillaries but has patchy distribution along the postcapillary venules. In capillaries, there is no clear separation of the endothelial and parenchymal basement membranes, and the basement membrane thus appears as a single entity that envelops the pericyte. In postcapillary venules, the parenchymal and endothelial basement membranes line the border of the virtual perivascular space (PVS). E: Endothelial cells, P: pericytes, A: Astrocyte endfeet.

As the arterioles diminish, smooth muscle cells are substituted with pericytes, which are embedded in the endothelial basement membrane ensheathing the endothelial cells. Also, the pial sheet disappears as the smooth muscle cells are lost along the arteriole branches.62 Thus, in the capillaries, the parenchymal and endothelial basement membrane appear as a single entity, which contains laminin 411 and 511 derived from endothelial cells and laminin 211 from astrocytes. The capillaries do not contain laminin 111 since they no longer receive a contribution from the pial cells (Figure 2).10,14,62 In postcapillary venules, the endothelial and parenchymal basement membranes are separated by a virtual perivascular space, which is especially apparent in cerebral inflammation where leukocytes accumulate in a perivascular cuff before infiltrating the brain parenchyma.33,61 Oppositely to arteries, arterioles, and capillaries, the endothelial basement membrane of the postcapillary venules exerts a patchy distribution of laminin 511, which has been correlated with sites where lymphocytes fail to extravasate.10

The contribution of the pericytes to the vascular basement membrane protein composition is considered significant due to the unique location of pericytes embedded in the endothelial basement membrane.63 For instance, recent data indicate that pericytes secrete both laminin 411 and 511 (Figure 2).9,22 Their secretion of basement membrane proteins is particularly prominent during development and angiogenesis.64 Additionally, the close relation between the BCECs and pericytes is considered important for induction of basement membrane protein synthesis by BCECs.63 The gene expression of collagen α1, laminin α4, laminin α5, agrin, and perlecan by murine BCECs is nonetheless unaffected when co-cultured with pericytes, indicating that interactions between BCECs and pericytes are not mandatory for expression of these basement membrane proteins.8

The function of the vascular basement membrane proteins

Looking at the function of the different basement membrane proteins, it should be emphasized that many of these proteins are also expressed in tissues and cells outside the CNS. Many genetic knockout models of specific basement membrane proteins exert loss of function with structural deformities in tissues outside the CNS that preclude their development further than the embryonic stage.65,66

The significance of different laminin isoforms in the brain was pursued by the creation of different murine laminin isoform knockouts. Knockout of the laminin α2 chain (LAMA2−/−) causes the autosomal recessive muscle disorder, laminin 2 deficient congenital muscular dystrophy. These mice show retarded growth and die at the age of 4–5 weeks.65 The LAMA2−/− mice also have a defect in the BBB as verified by the presence of inflammatory cells in the brain parenchyma, changed organization of tight junction proteins, reduced pericyte coverage, and extravasation of albumin. Together, these results suggest that α2-containing laminins from astrocytes are of great importance for both development and function of the BBB.67 The significance of astrocytic laminin was further investigated in γ1 null mice where the γ1 chain of laminin was specifically depleted in astrocytes resulting in faulty assembly of laminin 211. The γ1 laminin chain knockout mice exhibit weakened vascular integrity causing haemorrhages in small arterioles of the basal ganglia, thalamus, and hypothalamus. The weakened vasculature correlates well to a disrupted interaction between astrocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells.68 Depletion of astrocytic laminin is also associated with increased BBB permeability, confirmed by extravasation of albumin, IgG, and 500 kD FITC-Dextran, and decreased levels of the tight junction proteins, occludin and claudin-5 in brain capillaries. The astrocytic laminin also affects pericyte differentiation by maintaining the pericytes in a non-contractile state.11 The non-contractile form of pericytes is the primary cell type, which stabilizes BBB integrity.69 The ablation of astrocytic laminin and resulting changes in pericyte differentiation could be the reason for the weakened vascular integrity observed in the astrocytic laminin depleted mice.11 Laminin 411 and 511 produced by the BCECs also proved important for the vascular integrity and function of the BBB. In the experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) mouse model of multiple sclerosis, extravasation of inflammatory cells across the BBB selectively occurred at sites with sparse expression of laminin 511 in the endothelial basement membrane.10 Supporting this observation, deletion of endothelial laminin α4 also reduced migration of T cells across the BBB in the EAE model.70,71

Studies of collagen IV [α1(IV)]2α2(IV) knockout mice reveal that collagen IV is unnecessary for deposition of other basement membrane components during early embryonic development. However, the deletion causes embryonic lethality due to an impaired stability of the basement membrane at later embryonic age.66 Instead of creating a complete knockout of collagen IV, exon 39 of the collagen IV α1 chain was spliced directly to exon 41 creating the mouse model referred to as Col4a1Δex40. These mice develop haemorrhages in deep regions of the brain resembling the pathology of small vessel disease, which indicates that collagen IV is of great importance for maintaining proper function of the brain’s microvasculature.46,72

Knockout of nidogen-1 in mice causes neurological defects presented by episodes of involuntary movements, which resemble seizures and when lifted at its tail the knockout mice exhibit a twisted posture. Immunolabeling of other basement membrane proteins reveals that the vascular basement membrane is sufficiently formed in the absence of nidogen-1. However, brain capillaries had a thinned vascular basement membrane compared to the controls.51

Knockout of either perlecan or agrin is embryonic lethal.54 Perlecan deletion does not affect the formation of the vascular basement membrane; instead, the stability is affected causing, e.g., invasion of neuronal cells into the ectoderm during embryogenesis.73 Mice that completely lack the z+ splice form of agrin, also have a severe reduction of all other agrin isoforms including z0. The mice have slightly smaller brains compared to their age-matched control littermates and die at birth due to neuromuscular defects.74 Furthermore, the accumulation of agrin in the vascular basement membrane occurs at the developmental time when blood vessels become impermeable indicating that agrin supports BCECs during the formation of the BBB.57,75 This has been further supported by a murine study showing that the localization of the adherens junction proteins VE-cadherin, β-catenin, and ZO-1 in the BCECs is stabilized by the presence of agrin.58 This stabilizing effect of agrin is suggested to occur by binding to endothelial αvβ1 integrin since agrin previously has been shown to interact with αvβ1 integrin.58,76

Together, the basement membrane proteins play a significant role in the maintenance of the tightness of the BBB. This has been confirmed by various in vitro studies in which either immortalized or primary cell cultures were grown in transwell inserts mimicking the BBB.77 Growing primary porcine BCECs on filters coated with laminin, collagen IV, and fibronectin or a mixture of one-to-one of these proteins significantly increased the trans-endothelial electrical resistance (TEER) of BCEC monolayers. The greatest increase in TEER was observed when BCECs were grown on collagen IV, collagen IV/fibronectin, and fibronectin/laminin coated inserts.16 It should be noted that the ECM proteins employed in this study are neither specific for the CNS nor the endothelial basement membrane. Thus the increase in TEER does not necessarily correlate to in vivo conditions, where, e.g., fibronectin is not an integral component of the normal endothelial basement membrane. However, the importance of the basement membrane for maintaining barrier properties gains support by a recent study showing that porcine BCECs grown on pericyte and/or astrocyte generated basement membranes increase both the expression of the tight junction proteins occludin and claudin-5, and the electric resistance across porcine BCECs.78

Changes of the vascular basement membrane in stroke

Stroke is one of the most common causes of disability and death and is subdivided into ischemic and haemorrhagic stroke.79 Ischemic stroke occurs when the blood flow is interrupted by occlusion of brain-supplying arteries, whereas in haemorrhagic stroke a rupture in a weakened blood vessel evokes bleeding into the brain parenchyma. Stroke is accompanied by a release of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, oxidative stress, upregulation of proteases, compromised BBB integrity, oedema, and degradation of the vascular basement membrane.35,80,81 The compromised BBB causes leakage of serum components and migration of monocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages into the brain parenchyma. The migrating cells contribute to the inflammatory process by secreting proteases and inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. These responses result in a multitude of effects including loss of integrins important for endothelial cells, neuronal, oligodendrocyte, and astrocyte homeostasis together with modulation of the vascular basement membrane proteins.82–85 The precise mechanisms of the basement membrane modulation are not known, but results imply that basement membrane proteins like collagen IV, perlecan, agrin, laminin, and fibronectin can be degraded by proteases, which are upregulated following stroke (Table 3).35,81,86–88

Table 3.

Overview of the changes in basement membrane protein composition seen in stroke.

As previously mentioned, the Col4a1Δex40 mutation predisposes mice to haemorrhagic stroke, thus underlining the important role of collagen IV for vascular integrity.46,72 Likewise, mutations or degradation of other basement membrane proteins are suggested to predispose to stroke.72 The HSPG perlecan is lost in the ischemic core within hours following stroke in non-human primates.35 In the ischemic core, the cysteine proteases cathepsin B and L are both upregulated and hypothesized to be responsible for the degradation of perlecan since perlecan is the most sensitive basement membrane protein to proteolysis by these enzymes in vitro.35,89,90 The degradation of perlecan causes the generation of the protein fragments C-terminal domain V (DV) and LG3 of perlecan. Especially the production of perlecan DV is increased after ischemic stroke, and the generation of this fragment is proposed to play a protective role, since deficiency in perlecan leads to worsened stroke outcomes in a rodent model, while administration of perlecan DV improves the outcome.55,89 Degradation fragments of other basement membrane protein such as collagen IV may also influence the outcome of stroke, as collagen IV fragments have anti-angiogenic potential.91 Even though these fragments have been studied in relation to tumor angiogenesis92,93 they might also be involved in stroke pathogenesis.

Following stroke, the plasminogen activator system and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are also significantly upregulated. The plasminogen activator system is an enzymatic cascade, which is normally involved in fibrinolysis and thus clot degradation, matrix turnover, synaptic regulation, and plasticity in the developing and adult brain.94,95MMPs, a family of zinc endopeptidases, are produced in a latent form and contain a pro-peptide responsible for maintaining the latent form of MMP and a hemopexin-like domain, which can be recognized by tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMPs).96 The activity of these protease systems is highly regulated and depends on the developmental stage or the type of injury. A rapid increase in synthesis of urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) is observed following ischemic stroke.97,98 uPA is involved in the activation of plasminogen to plasmin, which contributes to fibrin degradation. In vitro studies reveal that plasmin is able to degrade both laminin and fibronectin and activate pro-MMPs. Consequently, the increased levels of plasmin seen in stroke may contribute to the degradation of the vascular basement membrane proteins.97–101 However, since PAI-1 is also upregulated,97,98 this might potentiate the effect of uPA and thus the involvement of plasmin in basement membrane degradation in vivo is not fully elaborated.

Several studies have shown an upregulation of pro-MMP-2 and -9 levels in the brain after stroke.97,98,102 Nonetheless, discrepancies in the time course of upregulation of the MMPs exist among species and models.98,102–104 Different enzymes or cytokines can activate MMPs through cleavage of the pro-domain or by a cysteine switch mechanism. Enzymes that are directly or indirectly involved in the activation of pro-MMP-2 include membrane-type 1-MMP (MT1-MMP), MT3-MMP, uPA, and plasmin, which are all upregulated following stroke.98,105 Additionally, the increased production of inflammatory cytokines, reactive nitrogen, and oxygen species produced after stroke, can trigger the secretion of MMP-9 and activation of pro-MMP-9.80,106–108 Both MMP-2 and -9 have a fibronectin binding domain allowing them to bind the basement membrane proteins and specifically digest fibronectin, collagen IV, and laminin in vitro.35,80,109 However, the active sites of MMP-2 and -9 do not accommodate the structure of native collagen IV or laminin, thus these basement membrane proteins have to be denatured to fit the active sites of the MMPs.110 Yet, an increased activation of MMP-2 and -9 could lead to digestion of the basement membrane proteins.35,87,88,109,111 Supporting this observation, scavenging the oxidative responses and thus inhibition of MMP-9 attenuates the loss of fibronectin 24 h after haemoglobin injection into the rat caudate nucleus.111 Furthermore, a significant reduction in the levels of agrin and SPARC is observed after global cerebral ischemia. MMP-2 and -9 are suggested to play a key role in this degradation.36,112 Although it might seem that MMPs are solely harmful, they probably have a dual role after haemorrhagic stroke. Thus, their expression is increased 1–3 and 7–14 days after stroke. Inhibition of MMPs during the acute phase improves the integrity of the BBB, whereas inhibition in the long-term probably interferes with the subsequent angiogenesis and remodeling. This indicates that the MMPs are involved in a pathological process in the acute phase on days 1–3 and conversely participate in a recovery process in the long-term phase around days 7–14.113 Even though the different protease systems are involved in changes of the BBB integrity following stroke, there is no direct evidence that the active forms of these proteases contribute to cerebral vascular basement membrane degradation in vivo.

Changes of the vascular basement membrane in Alzheimer’s disease

Oppositely to the changes of the basement membrane seen in ischemic and haemorrhagic stroke, the changes in AD include deposition of Aβ, basement membrane thickening, and changes in the basement membrane protein composition.

AD is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by continuous shrinkage of brain tissue and a gradual decline in memory and other cognitive functions.114 The pathological hallmarks of AD are extracellular amyloid plaques primarily composed of amyloid beta (Aβ) peptide and intracellular neurofibrillary tangles composed of hyperphosphorylated tau protein.114 Emerging evidence also indicates that vascular dysfunction is a third solid hallmark in AD.115–117

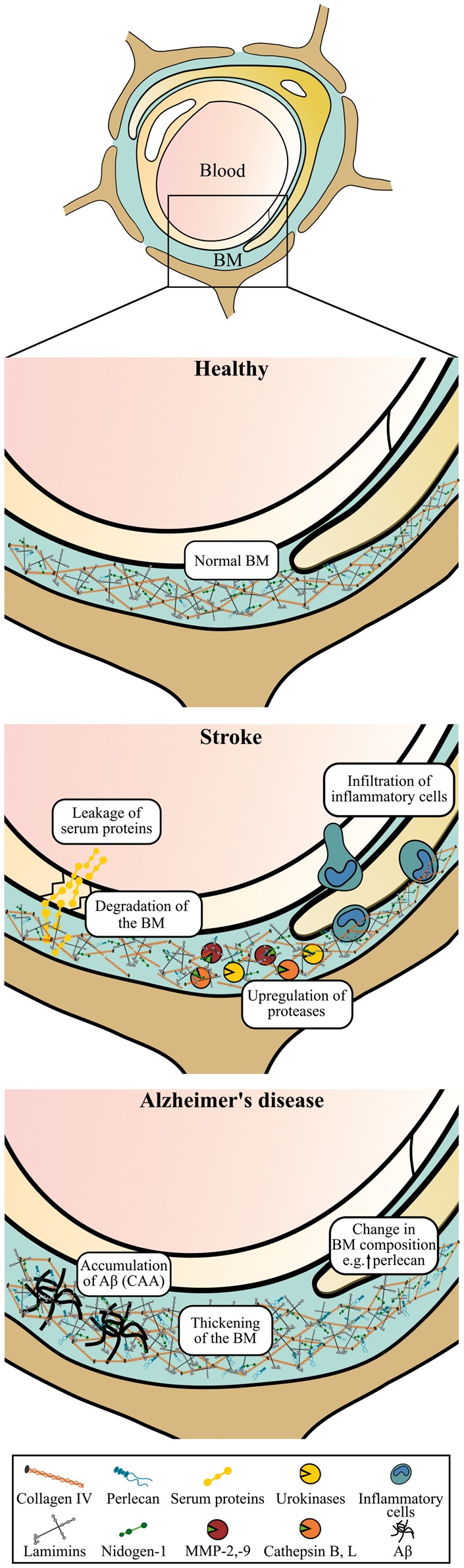

For years, the main hypothesis about the neuropathology of AD has been the ‘amyloid cascade hypothesis’, which states that the primary event in AD pathogenesis relates to the accumulation of Aβ. This notion is based on the fact that ∼1% of AD cases can be explained by genetic mutations in amyloid precursor protein (APP) or particular enzymes, secretases, which are involved in the sequential proteolysis of APP generating Aβ.118 However, the amyloid cascade hypothesis is challenged because a subset of the elderly has Aβ plaques without developing clinical symptoms of AD, suggesting that other factors could be involved in AD pathogenesis.119 The cause of the remaining ∼99% AD cases of apparently non-genetic, sporadic nature remains unknown. Yet, different risk factors have been identified with aging being the most evident, and an increasing amount of evidence also suggests that neurovascular dysfunction contributes to the neurodegeneration observed in AD prior to Aβ deposition.120 Increased risk of AD is also related to diabetes, obesity, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, atherosclerosis, and stroke, all factors that also contribute to pathological changes of the vasculature.121 For instance, changes in the composition of the vascular basement membrane are observed during normal aging and in conditions like diabetes and atherosclerosis.122–127 Thus the changes of the vascular basement membrane observed in AD may be initiated by another underlying vascular condition. Three distinct changes of the vascular basement membrane can be seen in AD, i.e. (i) deposition of Aβ, (ii) basement membrane thickening, and (iii) changes in the basement membrane protein composition (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the vascular basement membrane at the blood-brain barrier (BBB) in health, stroke, and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Normally the vascular basement membrane is well organized. In stroke, the basement membrane (continued) Figure 3. continued. proteins are degraded by mechanisms that may involve different protease-systems, e.g. matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) such as MMP-2 and -9, urokinases of the plasminogen activator system, and the cysteine proteases cathepsin B and L. Stroke is also accompanied by decreased BBB integrity with leakage of serum proteins, increased production of inflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen species, and invasion of inflammatory cells. Oppositely, in AD, accumulation of amyloid beta (Aβ) as cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA) in the basement membrane of both larger vessels and capillaries is observed. Furthermore, basement membrane thickening and changes in the protein composition of the basement membrane with increased deposition of, e.g., perlecan can also be seen in AD. BM: Basement membrane.

i) The resulting pathology occurring from the deposition of Aβ in the vasculature is referred to as cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA). Aβ can accumulate within the walls of pial and parenchymal arteries, arterioles, capillaries, and veins, and it is identifiable in approximately 80% of AD cases. A recent study, analyzing postmortem brain samples from 134 AD patients, found that the distribution of senile plaques and CAA could be categorized into four types. Type 1 cases had predominantly senile plaques with or without CAA in the pial vessels; type 2 cases had senile plaques and CAA in both the pial vessel walls and penetrating arteries; type 3 cases had senile plaques and CAA in predominantly capillaries and arteries; and type 4 cases had a more vascular phenotype, in which Aβ deposition was more dominant in CAA than in the senile plaques. Hence, the presentation of CAA in AD is quite heterogeneous.128

CAA in the pial and parenchymal vessel can also be found in non-demented individuals, and the identification of CAA thus does not positively correlate with AD or with the severity of AD. A study analyzing autopsies from 100 demented and non-demented individuals identified a small but significant correlation between the presence of CAA in capillaries and AD (Figure 3), suggesting that there might be different mechanisms involved in the development of CAA in capillaries and in the pial and larger parenchymal vessels.129 Genetics denotes an import factor for this difference since CAA in capillaries is associated with a higher frequency of individuals with the APO ɛ4 allele, and thus impact the heterogeneous presentation of CAA.128,130,131

In capillary CAA, Aβ is deposited as small bumps lining the basement membrane of the capillary wall (Figure 3), whereas in larger vessels the Aβ deposition is prominent in the tunica media in closer proximity to the smooth muscle cells.130 The distribution of Aβ in the vessel walls correlates with the perivascular drainage of solutes from the brain. Fluorescent tracers injected into the brain parenchyma initially spread along the extracellular spaces and along the endothelial basement membrane of the capillaries, and then along the basement membrane of the smooth muscle cells of the tunica media.132 Aβ1-40 isoform is the main form that accumulates in vessels, which contrasts the isoform found within amyloid plaques of the brain parenchyma denoted by the Aβ1-42 isoform.133 The cause of the Aβ deposition in the vessel wall remains unknown but it is linked to both a decreased clearance of Aβ across the BBB and thickening of the basement membrane.133,134

ii) Basement membrane thickening is observed in both capillaries of AD patients and rodent AD models (Table 4 and Figure 4).38,135–137 The causes of the basement membrane thickening have not been fully elaborated, and the cell types responsible for its thickening are unknown. Nevertheless, the thickening must be seen as a consequence of an imbalance between the synthesis rate and the degradation of the basement membrane proteins.138 It was suggested that astrocytes could be responsible for the basement membrane thickening, as only the parenchymal basement membrane, presumably synthesized by astrocytes, is affected, whereas the endothelial basement membrane remains normal as revealed by a study using immune electron microscopy.137 This suggests that the increased production of basement membrane proteins originates primarily from astrocytes, possible pericytes, but not endothelial cells. The thickening of the capillary basement membrane is predominantly found in areas affected by AD neuropathology,37,38 thus indicating a connection between the brain pathology with the thickening of the basement membrane. It is also suggested that the thickening of the basement membrane is initiated before deposition of Aβ deposition in the vessel wall since it is reported that thickening of the basement membrane occurs before the deposition of Aβ filaments in the vessel wall.139

Table 4.

Overview of the changes in basement membrane protein composition seen in Alzheimer’s disease.

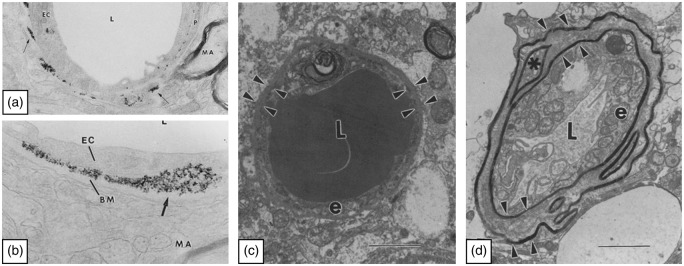

Figure 4.

Images showing the restrictive capabilities of the basement membrane and its thickening in Alzheimer’s disease. (a, b) The images illustrate the distribution of the iron particles Feridex along the basement membrane, after experimental opening of the blood-brain barrier using mannitol. The images are adapted from Muldoon et al.150 Permission American Society for Neuroradiology. L: Lumen, EC: endothelial cell, BM: basement membrane, MA: myelinated axon. (c, d) Images of capillaries from a patient with AD in a region with only few amyloid plaques (c) and a region severely affected by plaques (d). The arrowheads outline the basement membrane as a thin line in the region with only few plaques and in the regions severely affected by plaques the basement membrane have regional thickenings. The images are adapted from Perlmutter.166 L: Lumen, e: endothelial cell. Permission Springer Nature.

iii) The distribution of individual basement membrane proteins also appears altered in AD, although the reported changes are inconsistent (Table 4). Most studies observing basement membrane thickening also detect increase in collagen IV or report on the deposition of collagen fibrils in the thickened basement membrane.38,135–137 However, in some animal models of AD, the amount of collagen IV decreases over time, which may indicate that remodelling of the basement membrane is a continuous process in AD.37,140,141 Also, this suggests that the vascular basement membrane is being remodelled early and not later in the progression of AD as indicated above, as the preclinical murine models only allow for study up until approximately two years. Supporting the notion that the remodelling of the basement membrane is a continuous process, the basement membrane proteins such as laminins, collagen IV, and nidogen can disrupt the formation of Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 fibrils.142,143 Thus, the secretion of these proteins may be a reactive phenomenon to prevent Aβ fibrillation and strengthen the vessel wall by increasing the basement membrane thickness.139 In addition to the changed expression of collagen IV, the amount of both perlecan and fibronectin is also increased in both capillaries in AD transgenic mouse models and in postmortem brain samples from AD patients.37,38,140 Such changes could accelerate the accumulation of Aβ in the vessel wall as the disease progresses, since perlecan accelerates Aβ fibril formation and stabilizes newly formed fibrils.144

Although some findings are contradictory, the different studies covered above together suggest that the initial changes in the basement membrane composition with increased deposits of collagen IV and laminin occur to protect against increased levels of Aβ fibrils in the AD brain. This would gradually lead to vessel wall rigidity and reduced cerebral blood flow, hence creating the basis for accumulation of Aβ and subsequent CAA and capillary sprouting.115,145 The reduced cerebral blood flow was further correlated to the accumulation of Aβ in the AD brain.146 As the disease progresses, the basement membrane may gradually change and favour the deposition of perlecan and fibronectin on behalf of laminin and collagen IV, which will increase the propensity towards Aβ fibrillation,37,144 hence justifying the idea of the basement membrane being responsive before Aβ starts to deposit, but certainly without beneficial long-term effects.

Drug delivery strategies to obtain blood to brain transport can be hampered by the vascular basement membrane

The BBB constitutes a barrier to most pharmacological drugs, allowing only small drugs to enter the brain.147 A variety of drug-delivery strategies were developed to enable BBB passage, some of which are reviewed in following paragraphs with emphasis on additional permeability restraints of the vascular basement membrane to soluble molecules and nanoparticles. The vascular basement membrane provides a route for transport of soluble proteins like Aβ from the interstitial fluid of the brain parenchyma. These proteins can diffuse alongside the vascular basement membrane and gradually enter the surface of the brain, or they can transverse through the vascular basement membrane and leave the brain via BCECs.2 These transport routes are also followed when compounds like pharmaceuticals and large proteins are subjected to brain delivery following intrathecal-, intracerebroventricular-, convection-enhanced-, or intranasal delivery.148 The vascular basement membrane does not constitute a barrier to waste products leaving the brain under normal physiological conditions.2 In stroke, degradation of the vascular basement membrane is observed and in AD, Aβ can accumulate in the basement membrane hence contributing to the formation of CAA.35,149 Thus, both conditions may compromise routes for diffusion along the vascular basement membrane.

The basement membrane can also form a significant barrier situated beyond the BBB to some nanoparticles passaging through BCECs. This was evidenced in vivo in an experimental model with hyperosmolar opening of the tight junctions of the BCECs in where nanoparticles, of varying size (20–150 nm) and surface charge, were injected into the circulation. All the injected nanoparticles were able to passage the BCECs but some of the nanoparticles failed to transverse through the vascular basement membrane. The gathering of the nanoparticles at the vascular basement membrane was proposed to relate to the physical properties of the iron particles rather than their size suggesting that negative surface charge of the nanoparticles is of importance for interactions between nanoparticles and proteins of the vascular basement membrane (Figure 4).150

Relatively few studies have investigated the possible barrier properties of the vascular basement membrane to medication and reagents. Three recent studies examined the entry of nanoparticles to the brain parenchyma using focused ultrasound, which induces a transient opening of the BBB that allows for paracellular transfer in between BCECs.151–153 While these studies detected passaging across the BBB of nanoparticles varying in size from 50 nm to 240 nm,151–153 they did not elucidate whether nanoparticles were distributed inside the brain parenchyma, and it was not possible to reveal their distribution further with respect to possible localization inside the basement membrane.

As previously mentioned, the vascular basement membrane also provides a reservoir for soluble factors. This can also include important vascular growth factors and neurotrophic factors with therapeutic potential being continuously expressed and secreted in the adult brain.154,155 A strategy to further allow such growth factors to enter the brain is to transfect BCECs with cDNA injected into the circulation.156–158 Thus, the binding capacity of the vascular basement membrane must be taken into consideration when designing delivery strategies across the BBB, as the growth factors could get trapped there.

Generation of therapeutic antibodies targeted to the diseased brain constitutes promising candidates for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. The creation of bispecific antibodies targeting both transferrin receptors (TfRs) of BCECs and a neuronal target of the diseased brain parenchyma shows great potential.159,160 In the studies conducted by Yu et al.,160 bispecific antibodies were designed to target TfRs and the β-secretase, which is involved in the cleavage of amyloid precursor protein and subsequent generation of Aβ. These bispecific antibodies led to decreased Aβ deposition in the brain parenchyma making it plausible that bispecific antibodies are indeed able to pass the brain’s vascular basement membrane and reach their target within the brain parenchyma.159,160

Nanoparticles like liposomes are also tested for their transport across the intact BBB. Liposomes are small vesicles consisting of a double layer of phospholipids, which are usable for delivery of drugs either encapsulated in an aqueous core, in a lipid layer or adhered to the surface of the liposomes.161 When designing liposomes, the charge of the surface denotes an important parameter since anionic sites are located both at the surface of the BCECs and in the vascular basement membrane.162 An understanding of the physical and chemical interaction between the drug carrier and the basement membrane is important to predict if the particle will pass or accumulate within the basement membrane.163 Liposomes only diffuse within the ECM provided the surface charge of the particles are maintained within a well-defined window, largely independently of size,164 which is in good accordance with experiments performed on iron particles mentioned above.150 The potential of nanoparticles for passaging the BBB and basement membranes was recently reviewed with respect to experimental approaches for studies using in vitro models of the BBB.165 The filtering effect of the ECM on the nanoparticles could not be demonstrated when laminin or collagen IV alone were used to form the matrix,164 which emphasizes the importance of the complex nature of the vascular basement membrane in constituting multiple intertwined proteins.

Perspective

The vascular basement membrane is differently affected in acute and chronic pathological settings.

Stroke is accompanied by degradation of basement membrane proteins and a general loss of BBB integrity. Simultaneously, an increase in the expression of different protease systems capable of cleaving basement membrane proteins is also observed. However, a clear causal relationship between increased protease activity and protein degradation in vivo has not been firmly established, although suggestive temporal and topographical correlations have been shown by several groups. How the major changes in molecular composition and thickening of the basement membrane in AD occur is not well established. Thus, the mechanisms underlying the structural changes of the basement membrane deserve further investigation. Halting the composite changes of the basement membrane in neurodegeneration could possibly ease the delivery of macromolecular drugs and nanoparticles into the brain, and curtail the changes in acute stroke could limit barrier leakage and haemorrhagic consequences.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Paulsson M. Basement membrane proteins: structure, assembly, and cellular interactions. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 1992; 27: 93–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morris AW, Sharp MM, Albargothy NJ, et al. Vascular basement membranes as pathways for the passage of fluid into and out of the brain. Acta Neuropathol 2016; 131: 725–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abbott NJ, Ronnback L, Hansson E. Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci 2006; 7: 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daneman R, Zhou L, Agalliu D, et al. The mouse blood-brain barrier transcriptome: a new resource for understanding the development and function of brain endothelial cells. PLoS One 2010; 5: e13741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichota J, Skjorringe T, Thomsen LB, et al. Macromolecular drug transport into the brain using targeted therapy. J Neurochem 2010; 113: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abbott NJ, Patabendige AA, Dolman DE, et al. Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol Dis 2010; 37: 13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armulik A, Genove G, Mae M, et al. Pericytes regulate the blood-brain barrier. Nature 2010; 468: 557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomsen MS, Birkelund S, Burkhart A, et al. Synthesis and deposition of basement membrane proteins by primary brain capillary endothelial cells in a murine model of the blood-brain barrier. J Neurochem 2016; 140: 741–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gautam J, Zhang X, Yao Y. The role of pericytic laminin in blood brain barrier integrity maintenance. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 36450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sixt M, Engelhardt B, Pausch F, et al. Endothelial cell laminin isoforms, laminins 8 and 10, play decisive roles in T cell recruitment across the blood-brain barrier in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Cell Biol 2001; 153: 933–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yao Y, Chen ZL, Norris EH, et al. Astrocytic laminin regulates pericyte differentiation and maintains blood brain barrier integrity. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engelhardt B, Sorokin L. The blood-brain and the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers: function and dysfunction. Semin Immunopathol 2009; 31: 497–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Timpl R. Structure and biological activity of basement membrane proteins. Eur J Biochem 1989; 180: 487–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hallmann R, Horn N, Selg M, et al. Expression and function of laminins in the embryonic and mature vasculature. Physiol Rev 2005; 85: 979–1000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rauch U, Zhou XH, Roos G. Extracellular matrix alterations in brains lacking four of its components. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005; 328: 608–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tilling T, Korte D, Hoheisel D, et al. Basement membrane proteins influence brain capillary endothelial barrier function in vitro. J Neurochem 1998; 71: 1151–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yonezawa T, Hattori S, Inagaki J, et al. Type IV collagen induces expression of thrombospondin-1 that is mediated by integrin alpha1beta1 in astrocytes. Glia 2010; 58: 755–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Sloan SA, Clarke LE, et al. Purification and characterization of progenitor and mature human astrocytes reveals transcriptional and functional differences with mouse. Neuron 2016; 89: 37–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Utriainen A, Sormunen R, Kettunen M, et al. Structurally altered basement membranes and hydrocephalus in a type XVIII collagen deficient mouse line. Hum Mol Genet 2004; 13: 2089–2099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rauch U. Brain matrix: structure, turnover and necessity. Biochem Soc Trans 2007; 35: 656–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lau LW, Cua R, Keough MB, et al. Pathophysiology of the brain extracellular matrix: a new target for remyelination. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013; 14: 722–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jucker M, Tian M, Norton DD, et al. Laminin alpha 2 is a component of brain capillary basement membrane: reduced expression in dystrophic dy mice. Neuroscience 1996; 71: 1153–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engelhardt B. beta1-integrin/matrix interactions support blood-brain barrier integrity. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011; 31: 1969–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winder SJ. The complexities of dystroglycan. Trends Biochem Sci 2001; 26: 118–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaccaria ML, Di Tommaso F, Brancaccio A, et al. Dystroglycan distribution in adult mouse brain: a light and electron microscopy study. Neuroscience 2001; 104: 311–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barczyk M, Carracedo S, Gullberg D. Integrins. Cell Tissue Res 2010; 339: 269–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paulus W, Baur I, Schuppan D, et al. Characterization of integrin receptors in normal and neoplastic human brain. Am J Pathol 1993; 143: 154–163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milner R, Campbell IL. Increased expression of the beta4 and alpha5 integrin subunits in cerebral blood vessels of transgenic mice chronically producing the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 or IFN-alpha in the central nervous system. Mol Cell Neurosci 2006; 33: 429–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milner R, Campbell IL. Developmental regulation of beta1 integrins during angiogenesis in the central nervous system. Mol Cell Neurosci 2002; 20: 616–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grazioli A, Alves CS, Konstantopoulos K, et al. Defective blood vessel development and pericyte/pvSMC distribution in alpha 4 integrin-deficient mouse embryos. Dev Biol 2006; 293: 165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osada T, Gu YH, Kanazawa M, et al. Interendothelial claudin-5 expression depends on cerebral endothelial cell-matrix adhesion by beta(1)-integrins. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2011; 31: 1972–1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bashkin P, Doctrow S, Klagsbrun M, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor binds to subendothelial extracellular matrix and is released by heparitinase and heparin-like molecules. Biochemistry 1989; 28: 1737–1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song J, Wu C, Korpos E, et al. Focal MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity at the blood-brain barrier promotes chemokine-induced leukocyte migration. Cell Rep 2015; 10: 1040–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yousif LF, Di Russo J, Sorokin L. Laminin isoforms in endothelial and perivascular basement membranes. Cell Adh Migr 2013; 7: 101–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukuda S, Fini CA, Mabuchi T, et al. Focal cerebral ischemia induces active proteases that degrade microvascular matrix. Stroke 2004; 35: 998–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baumann E, Preston E, Slinn J, et al. Post-ischemic hypothermia attenuates loss of the vascular basement membrane proteins, agrin and SPARC, and the blood-brain barrier disruption after global cerebral ischemia. Brain Res 2009; 1269: 185–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hawkes CA, Gatherer M, Sharp MM, et al. Regional differences in the morphological and functional effects of aging on cerebral basement membranes and perivascular drainage of amyloid-beta from the mouse brain. Aging Cell 2013; 12: 224–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lepelletier FX, Mann DM, Robinson AC, et al. Early changes in extracellular matrix in Alzheimer's disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2015; 43: 167–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McKee KK, Harrison D, Capizzi S, et al. Role of laminin terminal globular domains in basement membrane assembly. J Biol Chem 2007; 282: 21437–21447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yurchenco PD. Integrating activities of laminins that drive basement membrane assembly and function. Curr Top Membr 2015; 76: 1–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hohenester E, Yurchenco PD. Laminins in basement membrane assembly. Cell Adh Migr 2013; 7: 56–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baeten KM, Akassoglou K. Extracellular matrix and matrix receptors in blood-brain barrier formation and stroke. Dev Neurobiol 2011; 71: 1018–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ljubimova JY, Fujita M, Khazenzon NM, et al. Changes in laminin isoforms associated with brain tumor invasion and angiogenesis. Front Biosci 2006; 11: 81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yurchenco PD, Schittny JC. Molecular architecture of basement membranes. FASEB J 1990; 4: 1577–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rowe RG, Weiss SJ. Breaching the basement membrane: who, when and how? Trends Cell Biol 2008; 18: 560–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gould DB, Phalan FC, Breedveld GJ, et al. Mutations in Col4a1 cause perinatal cerebral hemorrhage and porencephaly. Science 2005; 308: 1167–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cummings CF, Pedchenko V, Brown KL, et al. Extracellular chloride signals collagen IV network assembly during basement membrane formation. J Cell Biol 2016; 213: 479–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yurchenco PD, Furthmayr H. Self-assembly of basement membrane collagen. Biochemistry 1984; 23: 1839–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fox JW, Mayer U, Nischt R, et al. Recombinant nidogen consists of three globular domains and mediates binding of laminin to collagen type IV. EMBO J 1991; 10: 3137–3146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Salmivirta K, Talts JF, Olsson M, et al. Binding of mouse nidogen-2 to basement membrane components and cells and its expression in embryonic and adult tissues suggest complementary functions of the two nidogens. Exp Cell Res 2002; 279: 188–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dong L, Chen Y, Lewis M, et al. Neurologic defects and selective disruption of basement membranes in mice lacking entactin-1/nidogen-1. Lab Invest 2002; 82: 1617–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hopf M, Gohring W, Kohfeldt E, et al. Recombinant domain IV of perlecan binds to nidogens, laminin-nidogen complex, fibronectin, fibulin-2 and heparin. Eur J Biochem 1999; 259: 917–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sasaki T, Gohring W, Pan TC, et al. Binding of mouse and human fibulin-2 to extracellular matrix ligands. J Mol Biol 1995; 254: 892–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sarrazin S, Lamanna WC, Esko JD. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011; 3: 1–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roberts J, Kahle MP, Bix GJ. Perlecan and the blood-brain barrier: beneficial proteolysis? Front Pharmacol 2012; 3: 155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gohring W, Sasaki T, Heldin CH, et al. Mapping of the binding of platelet-derived growth factor to distinct domains of the basement membrane proteins BM-40 and perlecan and distinction from the BM-40 collagen-binding epitope. Eur J Biochem 1998; 255: 60–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kroger S, Schroder JE. Agrin in the developing CNS: new roles for a synapse organizer. News Physiol Sci 2002; 17: 207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steiner E, Enzmann GU, Lyck R, et al. The heparan sulfate proteoglycan agrin contributes to barrier properties of mouse brain endothelial cells by stabilizing adherens junctions. Cell Tissue Res 2014; 358: 465–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yurchenco PD. Basement membranes: cell scaffoldings and signaling platforms. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011; 3: 1–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Whitelock JM, Melrose J, Iozzo RV. Diverse cell signaling events modulated by perlecan. Biochemistry 2008; 47: 11174–11183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Engelhardt B, Vajkoczy P, Weller RO. The movers and shapers in immune privilege of the CNS. Nat Immunol 2017; 18: 123–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang ET, Inman CB, Weller RO. Interrelationships of the pia mater and the perivascular (Virchow-Robin) spaces in the human cerebrum. J Anat 1990; 170: 111–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hill J, Rom S, Ramirez SH, et al. Emerging roles of pericytes in the regulation of the neurovascular unit in health and disease. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2014; 9: 591–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dore-Duffy P. Pericytes: pluripotent cells of the blood brain barrier. Curr Pharm Des 2008; 14: 1581–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miyagoe Y, Hanaoka K, Nonaka I, et al. Laminin alpha2 chain-null mutant mice by targeted disruption of the Lama2 gene: a new model of merosin (laminin 2)-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy. FEBS Lett 1997; 415: 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Poschl E, Schlotzer-Schrehardt U, Brachvogel B, et al. Collagen IV is essential for basement membrane stability but dispensable for initiation of its assembly during early development. Development 2004; 131: 1619–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Menezes MJ, McClenahan FK, Leiton CV, et al. The extracellular matrix protein laminin alpha2 regulates the maturation and function of the blood-brain barrier. J Neurosci 2014; 34: 15260–15280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen ZL, Yao Y, Norris EH, et al. Ablation of astrocytic laminin impairs vascular smooth muscle cell function and leads to hemorrhagic stroke. J Cell Biol 2013; 202: 381–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thanabalasundaram G, Schneidewind J, Pieper C, et al. The impact of pericytes on the blood-brain barrier integrity depends critically on the pericyte differentiation stage. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2011; 43: 1284–1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sorokin L. The impact of the extracellular matrix on inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2010; 10: 712–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu C, Ivars F, Anderson P, et al. Endothelial basement membrane laminin alpha5 selectively inhibits T lymphocyte extravasation into the brain. Nat Med 2009; 15: 519–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gould DB, Phalan FC, van Mil SE, et al. Role of COL4A1 in small-vessel disease and hemorrhagic stroke. N Engl J Med 2006; 354: 1489–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Costell M, Gustafsson E, Aszodi A, et al. Perlecan maintains the integrity of cartilage and some basement membranes. J Cell Biol 1999; 147: 1109–1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Serpinskaya AS, Feng G, Sanes JR, et al. Synapse formation by hippocampal neurons from agrin-deficient mice. Dev Biol 1999; 205: 65–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Barber AJ, Lieth E. Agrin accumulates in the brain microvascular basal lamina during development of the blood-brain barrier. Dev Dyn 1997; 208: 62–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Martin PT, Sanes JR. Integrins mediate adhesion to agrin and modulate agrin signaling. Development 1997; 124: 3909–3917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Helms HC, Abbott NJ, Burek M, et al. In vitro models of the blood-brain barrier: an overview of commonly used brain endothelial cell culture models and guidelines for their use. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 862–890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zobel K, Hansen U, Galla HJ. Blood-brain barrier properties in vitro depend on composition and assembly of endogenous extracellular matrices. Cell Tissue Res 2016; 365: 233–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Qureshi AI, Mendelow AD, Hanley DF. Intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet 2009; 373: 1632–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Katsu M, Niizuma K, Yoshioka H, et al. Hemoglobin-induced oxidative stress contributes to matrix metalloproteinase activation and blood-brain barrier dysfunction in vivo. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010; 30: 1939–1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hamann GF, Okada Y, Fitridge R, et al. Microvascular basal lamina antigens disappear during cerebral ischemia and reperfusion. Stroke 1995; 26: 2120–2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Haring HP, Akamine BS, Habermann R, et al. Distribution of integrin-like immunoreactivity on primate brain microvasculature. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1996; 55: 236–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gary DS, Mattson MP. Integrin signaling via the PI3-kinase-Akt pathway increases neuronal resistance to glutamate-induced apoptosis. J Neurochem 2001; 76: 1485–1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Corley SM, Ladiwala U, Besson A, et al. Astrocytes attenuate oligodendrocyte death in vitro through an alpha(6) integrin-laminin-dependent mechanism. Glia 2001; 36: 281–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Milner R, Hung S, Wang X, et al. Responses of endothelial cell and astrocyte matrix-integrin receptors to ischemia mimic those observed in the neurovascular unit. Stroke 2008; 39: 191–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wasserman JK, Schlichter LC. Minocycline protects the blood-brain barrier and reduces edema following intracerebral hemorrhage in the rat. Exp Neurol 2007; 207: 227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rosell A, Cuadrado E, Ortega-Aznar A, et al. MMP-9-positive neutrophil infiltration is associated to blood-brain barrier breakdown and basal lamina type IV collagen degradation during hemorrhagic transformation after human ischemic stroke. Stroke 2008; 39: 1121–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hamann GF, Liebetrau M, Martens H, et al. Microvascular basal lamina injury after experimental focal cerebral ischemia and reperfusion in the rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2002; 22: 526–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee B, Clarke D, Al Ahmad A, et al. Perlecan domain V is neuroprotective and proangiogenic following ischemic stroke in rodents. J Clin Invest 2011; 121: 3005–3023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gu YH, Kanazawa M, Hung SY, et al. Cathepsin L acutely alters microvessel integrity within the neurovascular unit during focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2015; 35: 1888–1900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mundel TM, Kalluri R. Type IV collagen-derived angiogenesis inhibitors. Microvasc Res 2007; 74: 85–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Colorado PC, Torre A, Kamphaus G, et al. Anti-angiogenic cues from vascular basement membrane collagen. Cancer Res 2000; 60: 2520–2526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kamphaus GD, Colorado PC, Panka DJ, et al. Canstatin, a novel matrix-derived inhibitor of angiogenesis and tumor growth. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 1209–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lindgren A, Lindoff C, Norrving B, et al. Tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in stroke patients. Stroke 1996; 27: 1066–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Adibhatla RM, Hatcher JF. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and matrix metalloproteinases in the pathogenesis of stroke: therapeutic strategies. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2008; 7: 243–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brkic M, Balusu S, Libert C, et al. Friends or foes: matrix metalloproteinases and their multifaceted roles in neurodegenerative diseases. Mediators Inflamm 2015; 2015: 620581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hosomi N, Lucero J, Heo JH, et al. Rapid differential endogenous plasminogen activator expression after acute middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke 2001; 32: 1341–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chang DI, Hosomi N, Lucero J, et al. Activation systems for latent matrix metalloproteinase-2 are upregulated immediately after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2003; 23: 1408–1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Liotta LA, Goldfarb RH, Brundage R, et al. Effect of plasminogen activator (urokinase), plasmin, and thrombin on glycoprotein and collagenous components of basement membrane. Cancer Res 1981; 41: 4629–4636. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Liotta LA, Goldfarb RH, Terranova VP. Cleavage of laminin by thrombin and plasmin: alpha thrombin selectively cleaves the beta chain of laminin. Thromb Res 1981; 21: 663–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lijnen HR, Van Hoef B, Lupu F, et al. Function of the plasminogen/plasmin and matrix metalloproteinase systems after vascular injury in mice with targeted inactivation of fibrinolytic system genes. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1998; 18: 1035–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Heo JH, Lucero J, Abumiya T, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases increase very early during experimental focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1999; 19: 624–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rosenberg GA, Estrada EY, Dencoff JE. Matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPs are associated with blood-brain barrier opening after reperfusion in rat brain. Stroke 1998; 29: 2189–2195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Clark AW, Krekoski CA, Bou SS, et al. Increased gelatinase A (MMP-2) and gelatinase B (MMP-9) activities in human brain after focal ischemia. Neurosci Lett 1997; 238: 53–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Monea S, Lehti K, Keski-Oja J, et al. Plasmin activates pro-matrix metalloproteinase-2 with a membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase-dependent mechanism. J Cell Physiol 2002; 192: 160–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ruhul Amin AR, Senga T, Oo ML, et al. Secretion of matrix metalloproteinase-9 by the proinflammatory cytokine, IL-1beta: a role for the dual signalling pathways, Akt and Erk. Genes Cells 2003; 8: 515–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wu B, Ma Q, Suzuki H, et al. Recombinant osteopontin attenuates brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Neurocrit Care 2011; 14: 109–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gursoy-Ozdemir Y, Can A, Dalkara T. Reperfusion-induced oxidative/nitrative injury to neurovascular unit after focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke 2004; 35: 1449–1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mun-Bryce S, Rosenberg GA. Matrix metalloproteinases in cerebrovascular disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1998; 18: 1163–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Eckhard U, Huesgen PF, Schilling O, et al. Active site specificity profiling of the matrix metalloproteinase family: proteomic identification of 4300 cleavage sites by nine MMPs explored with structural and synthetic peptide cleavage analyses. Matrix Biol 2016; 49: 37–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ding R, Feng L, He L, et al. Peroxynitrite decomposition catalyst prevents matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation and neurovascular injury after hemoglobin injection into the caudate nucleus of rats. Neuroscience 2015; 297: 182–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sole S, Petegnief V, Gorina R, et al. Activation of matrix metalloproteinase-3 and agrin cleavage in cerebral ischemia/reperfusion. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2004; 63: 338–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Chang JJ, Emanuel BA, Mack WJ, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9: dual role and temporal profile in intracerebral hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2014; 23: 2498–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Goate AM. Alzheimer's disease: the challenge of the second century. Sci Transl Med 2011; 3: 77sr1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Biron KE, Dickstein DL, Gopaul R, et al. Amyloid triggers extensive cerebral angiogenesis causing blood brain barrier permeability and hypervascularity in Alzheimer's disease. PLoS One 2011; 6: e23789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zlokovic BV. Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer's disease and other disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 2011; 12: 723–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Fonseca AC, Ferreiro E, Oliveira CR, et al. Activation of the endoplasmic reticulum stress response by the amyloid-beta 1-40 peptide in brain endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013; 1832: 2191–2203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Masters CL, Simms G, Weinman NA, et al. Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1985; 82: 4245–4249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Lee HG, Casadesus G, Zhu X, et al. Challenging the amyloid cascade hypothesis: senile plaques and amyloid-beta as protective adaptations to Alzheimer disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004; 1019: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Ujiie M, Dickstein DL, Carlow DA, et al. Blood-brain barrier permeability precedes senile plaque formation in an Alzheimer disease model. Microcirculation 2003; 10: 463–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.de la Torre JC. Preface: physiopathology of vascular risk factors in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis 2012; 32: 517–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Takada H, Nagata K, Hirata Y, et al. Age-related decline of cerebral oxygen metabolism in normal population detected with positron emission tomography. Neurol Res 1992; 14: 128–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Petit-Taboue MC, Landeau B, Desson JF, et al. Effects of healthy aging on the regional cerebral metabolic rate of glucose assessed with statistical parametric mapping. Neuroimage 1998; 7: 176–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Uspenskaia O, Liebetrau M, Herms J, et al. Aging is associated with increased collagen type IV accumulation in the basal lamina of human cerebral microvessels. BMC Neurosci 2004; 5: 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Johnson PC, Brendel K, Meezan E. Thickened cerebral cortical capillary basement membranes in diabetics. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1982; 106: 214–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Onodera H, Oshio K, Uchida M, et al. Analysis of intracranial pressure pulse waveform and brain capillary morphology in type 2 diabetes mellitus rats. Brain Res 2012; 1460: 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Farkas E, de Vos RA, Donka G, et al. Age-related microvascular degeneration in the human cerebral periventricular white matter. Acta Neuropathol 2006; 111: 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Allen N, Robinson AC, Snowden J, et al. Patterns of cerebral amyloid angiopathy define histopathological phenotypes in Alzheimer's disease. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2014; 40: 136–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Attems J, Jellinger KA. Only cerebral capillary amyloid angiopathy correlates with Alzheimer pathology–a pilot study. Acta Neuropathol 2004; 107: 83–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Rub U, et al. Two types of sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2002; 61: 282–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Love S, Chalmers K, Ince P, et al. Development, appraisal, validation and implementation of a consensus protocol for the assessment of cerebral amyloid angiopathy in post-mortem brain tissue. Am J Neurodegener Dis 2014; 3: 19–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Weller RO, Subash M, Preston SD, et al. Perivascular drainage of amyloid-beta peptides from the brain and its failure in cerebral amyloid angiopathy and Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol 2008; 18: 253–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Deane R, Zlokovic BV. Role of the blood-brain barrier in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2007; 4: 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Okoye MI, Watanabe I. Ultrastructural features of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Hum Pathol 1982; 13: 1127–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Mehta DC, Short JL, Nicolazzo JA. Altered brain uptake of therapeutics in a triple transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Pharm Res 2013; 30: 2868–2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Bourasset F, Ouellet M, Tremblay C, et al. Reduction of the cerebrovascular volume in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Neuropharmacology 2009; 56: 808–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Zarow C, Barron E, Chui HC, et al. Vascular basement membrane pathology and Alzheimer's disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1997; 826: 147–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Roy S, Ha J, Trudeau K, et al. Vascular basement membrane thickening in diabetic retinopathy. Curr Eye Res 2010; 35: 1045–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Merlini M, Meyer EP, Ulmann-Schuler A, et al. Vascular beta-amyloid and early astrocyte alterations impair cerebrovascular function and cerebral metabolism in transgenic arcAbeta mice. Acta Neuropathol 2011; 122: 293–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Hawkes CA, Sullivan PM, Hands S, et al. Disruption of arterial perivascular drainage of amyloid-beta from the brains of mice expressing the human APOE epsilon4 allele. PLoS One 2012; 7: e41636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Kurata T, Miyazaki K, Kozuki M, et al. Progressive neurovascular disturbances in the cerebral cortex of Alzheimer's disease-model mice: protection by atorvastatin and pitavastatin. Neuroscience 2011; 197: 358–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Kiuchi Y, Isobe Y, Fukushima K, et al. Disassembly of amyloid beta-protein fibril by basement membrane components. Life Sci 2002; 70: 2421–2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]