Abstract

Background

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is associated with a mortality of more than 30%. Only about 30% of patients with SAB recover sufficiently to return to independent living.

Method

This article is based on a selective review of pertinent literature retrieved by a PubMed search.

Results

Acute, severe headache, typically described as the worst headache of the patient’s life, and meningismus are the characteristic manifestations of SAH. Computed tomography (CT) reveals blood in the basal cisterns in the first 12 hours after SAH with approximately 95% sensitivity and specificity. If no blood is seen on CT, a lumbar puncture must be performed to confirm or rule out the diagnosis of SAH. All patients need intensive care so that rebleeding can be avoided and the sequelae of the initial bleed can be minimized. The immediate transfer of patients with acute SAH to a specialized center is crucially important for their outcome. In such centers, cerebral aneurysms can be excluded from the circulation either with an interventional endovascular procedure (coiling) or by microneurosurgery (clipping).

Conclusion

SAH is a life-threatening condition that requires immediate diagnosis, transfer to a neurovascular center, and treatment without delay.

Acute subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is a serious condition that affects not just the brain, but multiple other organ systems as well (1). Despite a steady reduction of mortality from acute SAH in recent years, from over 50% to approximately 35%, this entity is still associated with considerable morbidity and mortality (1, e1– e13). Ten to 25 percent of all patients with acute SAH die immediately after the bleed or before arrival at the hospital (e6). Approximately one-third ultimately remain permanently dependent on nursing care, and only 30% are able to return to independent living (1). The clinical outcome depends on multiple factors, including the severity of the acute bleed, the patient’s initial condition, the presence or absence of early rebleeding, and the presence or absence of delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI). Pulmonary and cardiac complications are also prognostically relevant (2).

Continual refinement of neurosurgical methods—in particular, the introduction of microsurgical operative techniques—has led to steady improvement in surgical outcomes (3). In addition to the operative treatment of aneurysms (clipping), an alternative method of treatment was developed by Guglielmi and others, in which the aneurysm is closed from within by the endovascular application of tiny metal spirals (coiling). This has now become a standard treatment: at present, 50–85% of all saccular intracranial aneurysms can be treated by the endovascular route. Over the period 2002–2008 alone, the rate of endovascular treatment of aneurysms rose from 17% to 58% (4).

Learning objectives

Morbidity.

Approximately one-third of all patients with aneurysmal SAH ultimately remain permanently dependent on nursing care, and only 30% are able to return to independent living.

Readers of this article should become able to:

recognize the clinical manifestations of acute SAH and the significance of accompanying manifestations in organs other than the brain,

know the specific diagnostic evaluation that is needed to confirm the presence of acute SAH, and

know the specific initial therapeutic measures that must be taken once an acute SAH has been diagnosed.

The incidence and causes of subarachnoid hemorrhage

The incidence of acute SAH has been estimated at 2–22 cases per 100 000 persons per year, and 60% of all acute subarachnoid hemorrhages arise in persons aged 40 to 60 (1, e6). This implies that a general practitioner can typically expect to see a patient with acute SAH perhaps once in every 7 or 8 years (e6).

The most common cause of basal acute SAH is a ruptured cerebral aneurysm. “Basal” means that the blood is most prominently seen in the basal cisterns. In the alternative situation of an acute perimesencephalic SAH, the blood is distributed around the midbrain; cortical acute SAH, on the other hand, is usually due to trauma. Intracranial aneurysms are now held to be acquired rather than congenital lesions (e6-e10 ). Their prevalence is approximately 2% (range, 1–6%). Their cause is unknown. 90% of all cerebral aneurysms are less than 1 cm in size and have a relatively low risk of bleeding (5). If a patient with acute basal SAH undergoes cerebral angiography and no aneurysm is found, repeated angiography is recommended within 10 days. Acute SAH in which no aneurysm can be demonstrated by angiography is due either to an event belonging to the class of perimesencephalic SAH, or else to a ruptured aneurysm that has subsequently become filled by thrombus and thus temporarily cannot be seen. Rarer causes include pathological vascular changes such as an arteriovenous malformation or fistula, vasculitis, arterial dissection, venous thrombosis, a tumor, or drug abuse (e6).

80–90% of all cerebral aneurysms are located in the anterior circulation of the brain (the internal carotid artery, the anterior and middle cerebral arteries, and their branches) and only 10–20% in the posterior circulation (the vertebral, basilar, and posterior cerebral arteries and their branches). Unruptured aneurysms are usually asymptomatic, yet in 5% of cases they can give rise to epileptic seizures or, if large, to a thromboembolic event or a neurologic deficit due to mass effect (e.g., an oculomotor nerve palsy).

Incidence.

The incidence of acute SAH has been estimated at 2–22 cases per 100 000 persons per year, and 60% of all acute subarachnoid hemorrhages arise in persons aged 40 to 60.

The mechanisms leading to aneurysm rupture are only partly known. Numerous intrinsic and extrinsic factors have been identified, including the size, location, configuration, surface characteristics, and hemodynamic features of the aneurysm (6– 13, e11– e23). Moreover, the known cardiovascular risk factors, such as arterial hypertension and cigarette smoking, and alcohol abuse have been found to promote the progressive increase of aneurysm size, finally leading to rupture (14, e13– e15).

Neurologic manifestations and classification

The main clinical feature of acute SAH is a very severe headache of sudden onset (often described as the worst headache of the patient’s life). Both the severity and acute onset of the headache are highly characteristic of SAH (e6). Patients who already suffered from chronic headache before having their SAH often state that the pain is of an entirely different nature and intensity. This is important, as such patients are in danger of having their headache misdiagnosed as, for example, a migraine attack. Acute SAH is also often associated with signs of meningeal irritation (meningismus, photophobia), signs of intracranial hypertension (nausea and vomiting, decline of consciousness ranging to coma), epileptic seizures, and focal neurologic deficits (1). The latter usually reflect cranial nerve dysfunction, intraparenchymal bleeding, or focal ischemia (e6).

Two different clinical schemes for the severity of acute SAH are now in use in Germany, namely, the Hunt and Hess classification (table 1) and the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (WFNS) classification (9, 10).

Table 1. The Hunt and Hess scale.

| Grade | Clinical features |

| 0 | Unruptured |

| I | Mild headache and nuchal stiffness, no neurologic deficit |

| II | Moderate headache and nuchal stiffness, no neurologic deficit except possibly a cranial nerve palsy |

| III | Somnolence, possible mild focal neurologic deficit |

| IV | Stupor, hemiparesis (mild to severe) |

| V | Coma |

Further manifestations

Acute SAH impairs not only the perfusion and the function of the central nervous system, but also multiple other organ systems as well.

Approximately 10% of patients with acute SAH have intraocular hemorrhages. In most cases, these are small, linear, preretinal subhyaloid hemorrhages near the optic disc. Severe preretinal hemorrhages can extend into the vitreous body (Terson syndrome [e6]).

Clinical hallmark.

The main clinical feature of acute SAH is a very severe headache of sudden onset (often described as the worst headache of the patient’s life). Both the severity and the acute onset of the headache are highly characteristic of SAH.

Cardiac complications are also very commonly seen after acute SAH. Cardiac manifestations reflect a disturbance of the physiological link between the nervous system and the heart: elevated catecholamine secretion after acute SAH can lead to myocardial necrosis and myocardial dysfunction. More than 90% of all patients with acute SAH have ECG abnormalities, and these can be very hard to distinguish from those of an acute myocardial infarction. Ischemic signs (ST elevation) are seen, as well as arrhythmias and prolongation of the QT segment.

The cardiac stress resulting from SAH can lead to hypotension, which, in turn, exacerbates already existing cerebral hypoperfusion (15, 16, e24).

These ECG changes may be attributed to a primary cardiac problem rather than an underlying acute SAH when the patient is initially seen in the emergency room, and there is thus a danger that the diagnosis of SAH will be overlooked (15, 16, e24). Excessively elevated catecholamine secretion after acute SAH can also cause pulmonary hypertension and pulmonary edema, leading to increased mortality (14– 16).

Electrolyte disturbances are another common finding after acute SAH, arising in approximately 30% of patients. The cause can be either cerebral salt-wasting syndrome or the syndrome of inappropriate ADH secretion (SIADH, also called Schwartz–Bartter syndrome) (15, 16, e24). Salt-wasting syndrome is characterized by hyponatremia with excessive loss of fluid and sodium in the urine, with resulting hypovolemia and an elevated risk of vasospasm. SIADH, on the other hand, is characterized by euvolemic hyponatremia.

Initial diagnostic imaging studies

Cardiac complications.

Cardiac complications are very commonly seen after acute SAH. Cardiac manifestations reflect a disturbance of the physiological link between the nervous system and the heart.

Severe headache of sudden onset combined with meningismus is the clinical hallmark of acute SAH. The diagnostic method of choice for demonstrating the presence of blood in the subarachnoid space is computed tomography (CT) of the head without intravenous contrast medium: this reveals blood as a hyperdense signal in the basal cisterns (and, if present, in the ventricular system and brain parenchyma). Within the first few hours after an acute SAH, CT has nearly 100% sensitivity and specificity for the detection of blood in the subarachnoid space; if the CT is negative, an acute SAH is practically ruled out in most cases (eFigure 1a) (17, e25– e27). Rarely, however, an acute SAH can involve only a “minor leak,” i.e., the entrance of such a small quantity of blood in the subarachnoid space that it cannot be detected by CT; if clinical suspicion warrants, a lumbar puncture should be performed (e6). Because CT becomes less sensitive for acute SAH over time, patients who present at longer latencies after the bleed also need a lumbar puncture to establish the diagnosis (17, e6). The so-called three-glass test has often been described as a method of distinguishing an acute SAH from bleeding caused by the puncture itself (a “traumatic tap”), but its reliability is debated. CSF spectrometry for the detection of bilirubin and CSF cytology for the detection of siderophages can be used to detect SAH even weeks after the event. A lumbar puncture is also useful in some cases to help rule out major differential diagnoses that may themselves be life-threatening, e.g., meningitis (18). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with multiple sequences in combination seems to be more sensitive than CT (19). If the CT is negative, it may be reasonable to perform an MRI as the next test. Nonetheless, MRI is not used routinely in the diagnostic evaluation of acute SAH (in contrast to acute cerebral ischemia), because it tends to be both logistically cumbersome and hard to interpret (20).

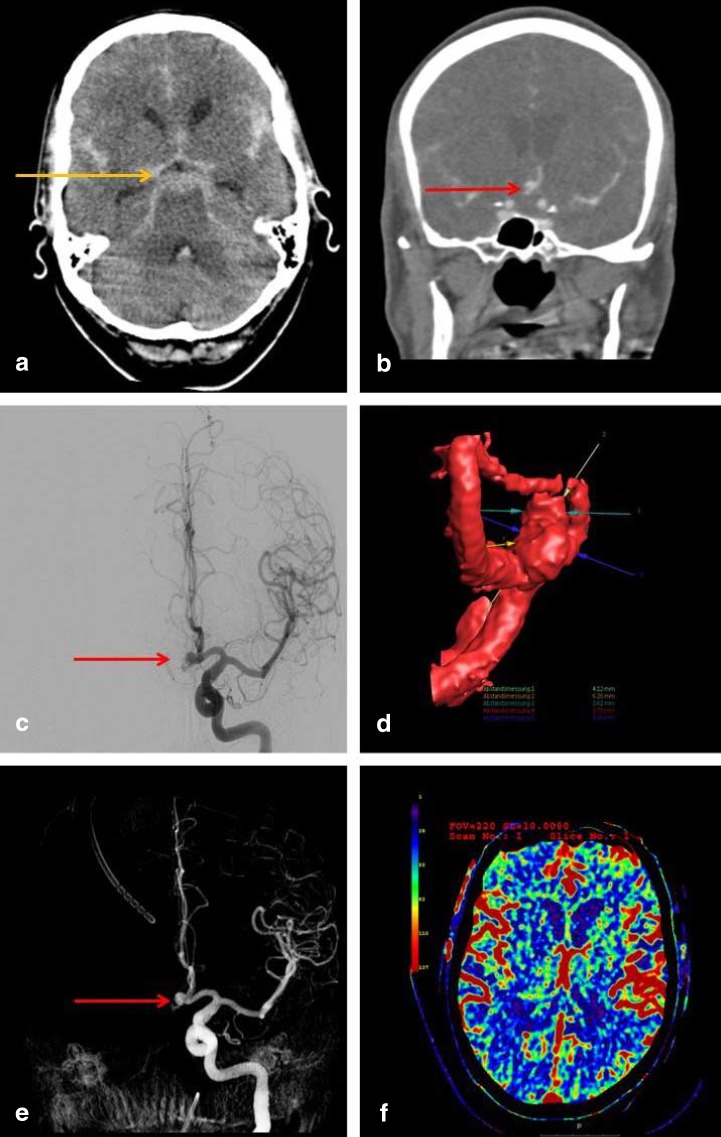

eFigure 1:

Imaging studies for the detection of subarachnoid hemorrhage and the determination of the source of bleeding.

These are the initial imaging studies obtained for a 63-year-old man who was admitted because of the sudden onset of the worst headache of his life, followed by a decline in consciousness. A computed tomogram (CT) of the head displays the classic pattern of a basal subarachnoid hemorrhage, with blood in the basal cisterns appearing as a hyperintense signal in the pentagonal cistern (image a, orange arrow). Subsequent CT angiography and digital subtraction angiography (images b, c) reveal an aneurysm of the anterior communicating artery as the source of bleeding (red arrows). The corresponding 3D reconstructions (images d and e) reveal the spatial configuration of the aneurysm and its spatial relationships to the nearby vessels. A perfusion CT (image f) enables visualization of cerebral perfusion: the parameter displayed here is the regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF)

Head CT.

Within the first few hours after an acute SAH, CT has nearly 100% sensitivity and specificity for the detection of blood in the subarachnoid space.

The gold standard for the detection of cerebral aneurysms as the source of bleeding in a basal acute SAH is digital subtraction angiography (DSA) (e25) (eFigure 1c– e), which enables good visualization of the site and configuration of the aneurysm, its ingoing and outgoing vessels, and its relation to the nearby vasculature. The important information that it provides serves as the basis for the planning of definitive treatment to secure the aneurysm. DSA carries a small risk of aneurysmal rebleeding (ca. 1–2%) as well as of new neurologic deficits (1.8% [e6]). CT angiography may be a reliable and sensitive alternative to DSA in some situations (e25) (eFigure 1b). Particularly when surgical intervention is urgently needed, as in patients with massive bleeding and signs of cerebral herniation, DSA should be dispensed with in favor of CT angiography. As long as the patient’s situation is not immediately life-threatening, however, DSA remains the imaging modality of choice, and CT angiography should not be substituted for it.

Early pathophysiological changes and complications

The early pathophysiological changes and complications after acute SAH are distinct from those that arise in the patient’s later course (i.e., from the third day onward). These early changes are designated by the term “early brain injury.” Immediately after an aneurysm ruptures and blood extravasates into the subarachnoid space, the intracranial pressure rises precipitously—sometimes to values above the diastolic blood pressure, up to 100 mmHg, blocking further extravasation (21– 23, e29– e49; for further information, see also e50, e52–e55, e57). As a rule, the intracranial pressure falls again within a few minutes, though usually not all the way back to the level that prevailed before the bleed.

Acute hydrocephalus, an intracerebral or (less commonly) subdural hematoma, and generalized cerebral edema are treatable further sequelae that can cause acute—and, often, potentially reversible—neurologic impairment in patients with acute SAH. A second acute SAH due to rebleeding of a ruptured aneurysm that has not yet been secured by clipping or coiling is a further clinically significant early complication (15% in the first 24 hours) (1, 15, e6). Aneurysmal re-rupture and second bleeds are associated with a mortality of 70–90%.

Initial management

Digital subtraction angiography.

The gold standard for the detection of cerebral aneurysms as the source of bleeding in a basal acute SAH is digital subtraction angiography (DSA).

Acute SAH is a life-threatening condition that is often incorrectly diagnosed at first, despite its characteristic clinical presentation; precise figures on misdiagnosed SAH are unavailable (23). Attention must be paid to meningismus, a common accompaniment of SAH. While patients who sustain a severe SAH and present with impaired consciousness generally undergo the appropriate diagnostic studies immediately, those with less severe hemorrhages can present diagnostic difficulties. In particular, in patients who already have a history of frequent headaches of a specific type (such as migraine, cluster headache, or cervicogenic headache), acute SAH may be mistakenly omitted from the differential diagnosis. The management of patients with acute SAH in the period before the source of the bleeding has been secured is aimed at preventing life-threatening complications and second bleeds, and thereby minimizing further damage to the brain (Figure 1, Table 2). Second bleeds in the first 24 hours often arise in association with transport and medical interventions; it is nonetheless clear that patients whose consciousness is impaired should be transferred to a neurovascular center as soon as possible, because any delay worsens the prognosis (23). All patients with acute SAH should immediately be taken to such a center (i.e., a hospital where specialized units for neurosurgery, neurology, and neuroradiology are present and have experience treating patients with aneurysmal SAH). Lieshout et al. showed in 2016 that delayed transport to a neurosurgical center, with prolongation of the interval from the onset of SAH to arrival in the center, significantly worsens mortality (23). Delayed transport is often accounted for by initial presentation to a hospital without a neurosurgical service, or else by an initial misdiagnosis (23). Patients with acute SAH initially misdiagnosed as suffering from coronary heart disease (CHD) suffered up to 75% mortality because of the time wasted in ruling out CHD (23). Until the aneurysm has been secured by clipping or coiling, the patient’s vital signs must be continuously monitored (with continuous recording of blood pressure and, in some cases, ECG), and the neurological status must be documented at close intervals as well (state of consciousness, Glasgow Coma Scale, pupillary responses, and any focal neurologic deficits). Rapid neurological, and possibly systemic, deterioration can occur at any time.

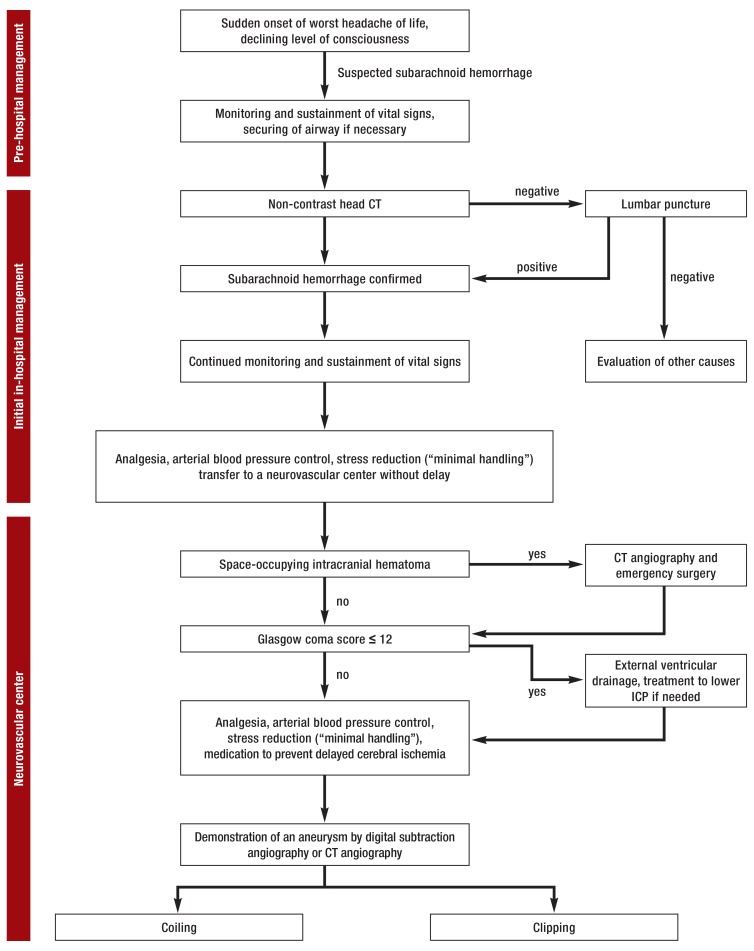

Figure 1.

Treatment algorithm for aneurysmal SAH

from the initial management until the securing of the aneurysm by coiling or clipping.

CT, computed tomography;

ICP, intracranial pressure;

SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage

Table 2. Basic therapeutic measures in acute subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and their evidential basis.

| Goal | EL | Measure | Therapeutic intervention by means of (e.g.): | |

| Monitoring vital signs | B | Frequent GCS determinations and monitoring of basic neurologic functions as required in accordance with clinical condition (e.g., continuous, every 15 minutes, or once per hour) | ||

| Securing vital signs | A | Intubation for GCS ≤ 12, respiratory insufficiency | ||

| Demonstration of SAH | B | Noncontrast head CT | ||

| Lumbar puncture if indicated (after head CT and exclusion of elevated intracranial pressure) | ||||

| Classification of severity | B | Classification of severity according to the WFNS and H & H scales | ||

| Transfer to a neurovascular center | B | Immediate transfer to a neurosurgical/neurovascular center | ||

| Stress reduction | C | Absolute or relative bed rest (depending on hospital) | ||

| Stress reduction (limited visits of relatives, no TV, …) | ||||

| Analgesics, sedatives, and stool softeners as needed | ||||

| Minimal handling: no needle sticks in awake patients other than for intravenous access | ||||

| Sedation if needed in case of restlessness or agitation (beware of respiratory depression, hypotension, and paradoxical reactions; the patient should remain awake enough for neurological examination) | Diazepam 5 mg po or iv prn | |||

| Analgesia | B | Administration of analgesic drugs | Dexamethasone 4 mg po or iv tid | |

| Paracetamol 1 g po qid | ||||

| Morphine 10 mg po as needed (iv for intubated patients) | ||||

| Blood pressure control | B | Target range for systolic blood pressure, 100–140 mm Hg | ||

| Treatment of hypertension | Primary: | nimodipine 60 mg po or iv q4h | ||

| Secondary: | nifedipine 20 mg po tid or qid | |||

| Tertiary: | urapidil iv bolus as a test, then possibly clonidine iv infusion | |||

| Treatment of hypotension | Primary: | balanced electrolyte solution, 100–150 mL/h | ||

| Secondary: | lower nimodipine dose | |||

| Tertiary: | administration of noradrenaline only in the intensive care unit (dangerous if the aneurysm has not yet been secured; only in exceptional cases) | |||

| Prophylaxis against DCI | A | Administration of nimodipine | ||

| Ulcer prophylaxis | C | Administration of a proton-pump inhibitor | Omeprazole 40 mg qd or bid | |

| Prevention of hypertension associated with defecation | C | Administration of a stool softener | ||

| Treatment of hydrocephalus | B | Insertion of an external ventricular drain (only in neurosurgical centers) or lumbar puncture if indicated | ||

Evidence grades and definitions:

A, different patient populations studied, data from multiple prospective and randomized trials or meta-analyses;

B, limited patient population studied, data from a small number of prospective and randomized trials or from non-randomized studies;

C, very limited patient population studied, consensus opinion, single studies, standard treatment.

DCI, delayed cerebral ischemia; EL, evidence level; GCS; Glasgow Coma Scale; H & H, Hunt and Hess; WFNS, World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies

Aneurysmal re-rupture.

Aneurysmal re-rupture and second bleeds are associated with a mortality of 70–90%.

Initial management.

The vital signs must be monitored and sustained and the airway must be secured. The patient must then be taken to a neurosurgical center.

Treatment in a neurovascular center.

If the patient has an intracerebral hemorrhage and the Glasgow coma score is = 12, pain should be treated, the arterial blood pressure controlled, stress reduced, and medication given to prevent delayed cerebral ischemia.

Because aneurysmal re-rupture carries a 70–90% mortality, all risk factors that can promote re-rupture need to be thoroughly addressed (7). Blood pressure control is particularly important: high blood pressure and rapid increases of blood pressure must be avoided. Keeping the systolic blood pressure below 140 mmHg is recommended (20). Absolute blood pressure may, however, be less important than relative increases in comparison to the patient’s usual premorbid blood pressure level. Suitable drugs for blood pressure control after acute SAH include urapidil, clonidine, and calcium antagonists. Sodium nitroprusside is not recommended, as it may raise the intracranial pressure (20). In addition to balanced blood pressure management, potential stress factors must be removed or treated, i.e., pain, agitation, and anxiety must be dealt with effectively. For this reason, the indication for any potentially painful procedure, such as arterial and central venous line placement, in an unsedated patient should be carefully considered. In a neurosurgical center, progressively worsening hydrocephalus and the accompanying rise in intracranial pressure can be effectively treated by the insertion of an external ventricular or lumbar drainage system. Life-threatening intraparenchymal or subdural hematomas require immediate neurosurgical evacuation; because of the risk of intraoperative aneurysm rupture, such procedures should only be performed by a neurosurgeon with adequate expertise in vascular neurosurgery.

Prevention in the treatment of patients with an acute SAH.

Ulcer prophylaxis

Stool softeners to prevent hypertension during defecation

Stress reduction

Blood pressure limits.

The systolic blood pressure should be kept in the 100–140 mm Hg range.

Securing the aneurysm—clipping or coiling?

Drugs for blood pressure control.

Suitable drugs for blood pressure control after acute SAH include urapidil, clonidine, and calcium antagonists. Sodium nitroprusside is not recommended, as it may raise the intracranial pressure.

Stress factors.

In addition to balanced blood pressure management, potential stress factors must be removed or treated, i.e., pain, agitation, and anxiety must be dealt with effectively.

The most effective way to prevent a second acute subarachnoid hemorrhage is to exclude the source of bleeding from the circulation. Securing ruptured cerebral aneurysms as early as possible has been shown to lessen mortality (24– 26). In particular, securing the aneurysm by the second day after the SAH seems to yield better outcomes than doing so at later times (15, 24, 27).

The surgical treatment of cerebral aneurysms originated with Walter E. Dandy in 1937 and has been steadily refined ever since (28). The aneurysm is closed off from its parent vessel by the placement of a metal clip to occlude its neck (eFigure 2). As an alternative to open surgery, a method of endovascular interventional treatment has been developed in which the aneurysm is occluded from within by the placement of platinum spirals (coils) inside it (29, 30). Figure 2 shows the endovascular treatment of an aneurysm of the posterior cerebral artery by stent implantation and coiling.

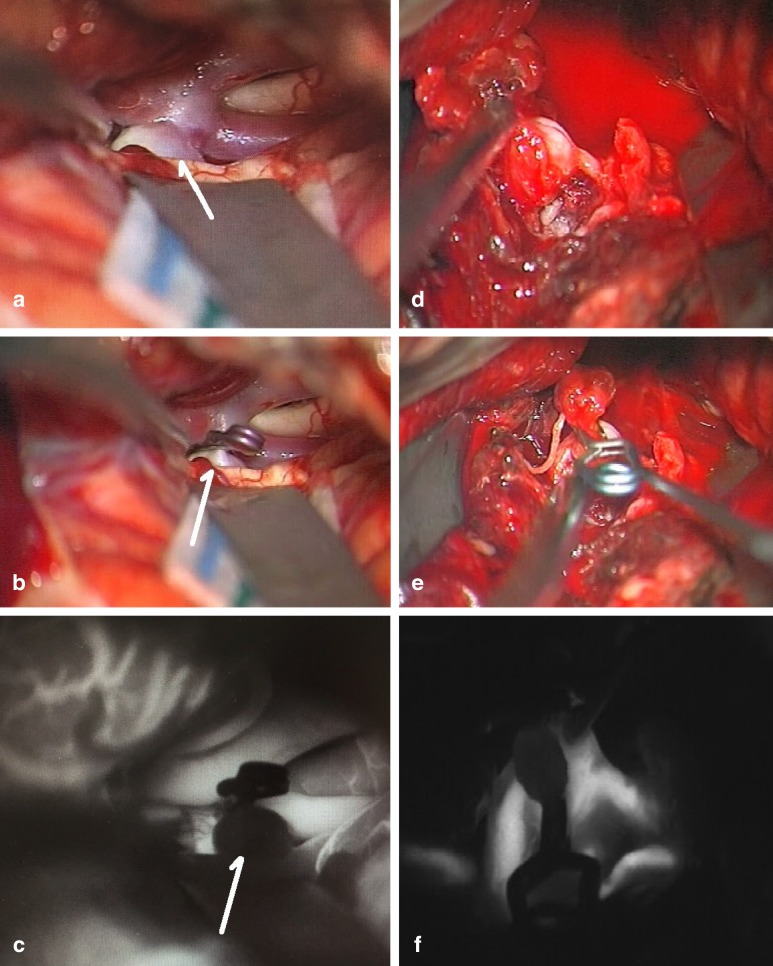

eFigure 2:

Intraoperative videoangiography with indocyanine green (ICG)

Intraoperative photograph of an (unruptured) aneurysm of the middle cerebral artery

Aneurysm clipping

ICG angiography displaying the cerebral vessels and confirming that the aneurysm has been secured

Ruptured aneurysm of the pericallosal artery. The vascular anatomy is obscured by subarachnoid blood.

The aneurysm has been secured with two clips.

ICG angiography showing that the aneurysm has been secured (no signal) and confirming intact distal vascular perfusion (in white)

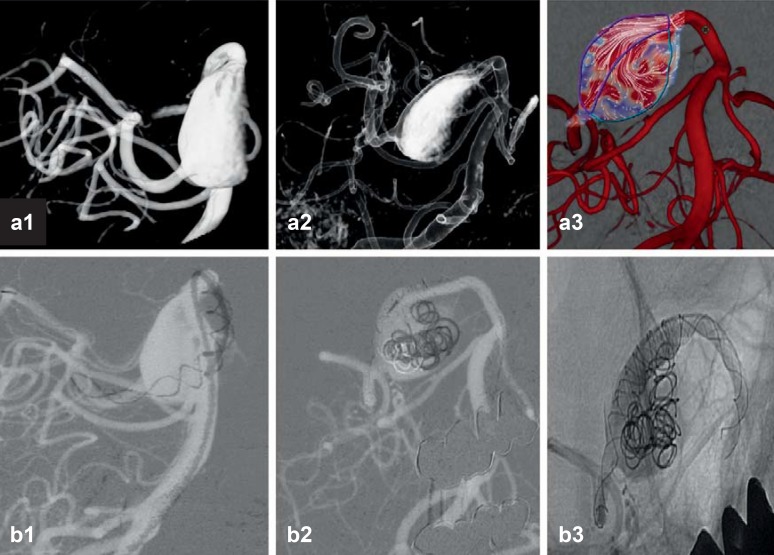

Figure 2.

Stenting and coiling of a complex aneurysm of the posterior cerebral artery

3D angiographic reconstruction of the complex aneurysm, a fusiform and partially thrombosed aneurysm that is not amenable to clipping. The image at right shows the flow vectors within the aneurysm.

A stent was placed in the vessel, and then coiling was performed through the stent. The patient tolerated the procedure well and was discharged from the hospital in good condition. If the attempt to place a stent had been unsuccessful, the neurosurgeons would have performed an operation to exclude the aneurysm from the circulation by trapping it and performing an arterial bypass around it

The choice of the optimal method for securing intracranial aneurysms is a topic on which there has been much discussion. Interdisciplinary consideration of each individual case by experts in both procedures, i.e., neurosurgeons and endovascular neuro-interventionalists, is essential and constitutes the current standard.

Endovascular interventional treatment is now considered the standard approach for aneurysms of the posterior circulation (particularly basilar tip aneurysms) because of the relatively high risk of surgical complications in these patients (31).

The surgical and endovascular interventional methods of securing aneurysms after acute SAH have now been compared in four prospective randomized and controlled trials and in numerous prospective and retrospective cohort studies. Two trials play a particularly important role, the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) and the Barrow Ruptured Aneurysm Trial (BRAT) (3, 31, 32). The findings of these two trials, as well as of meta-analyses, suggest that interventional treatment yields a significantly better clinical outcome 1 year later. This advantage seems to lessen on longer follow-up, however, as the reperfusion and rebleed rates of coiled aneurysms are apparently higher than those of surgically clipped aneurysms.

In conclusion, both surgical clipping and interventional coiling are now well-established methods for the treatment of cerebral aneurysms.

Late pathophysiological changes and complications

Clipping.

The aneurysm is closed off from its parent vessel by the placement of a metal clip to occlude its neck.

Beyond the time frame for so-called early brain injury, further important pathophysiological changes can arise from the third day after SAH onward. Cerebral vasospasm was at one time held to be responsible for late cerebral hypoperfusion and for ensuing neurological decompensation and poor clinical outcomes. The concept of cerebral vasospasm as the main factor leading to poor outcomes in patients with acute SAH has been called into question, however, now that multiple clinical trials (e.g., the CONSCIOUS-1 trial) have shown that a decrease in the incidence of cerebral vasospasm is not necessarily accompanied by a corresponding improvement in outcome. The complex syndrome of delayed cerebral hypoperfusion and neurological decompensation is now called delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) (33– 35, e51, e57– e80).

DCI can manifest itself clinically as gradual neurological deterioration over the course of several hours, as a decline in the state of consciousness (a drop of more than 2 points on the Glasgow Coma scale), or as a focal neurologic deficit of acute onset (e.g., hemiparesis, aphasia, apraxia, or neglect).

Transcranial Doppler sonography (TCD) with determination of the so-called Lindegaard index is the conventional way to detect cerebral vasopasm after acute SAH (35, e70).

Specific pharmacotherapy for DCI consists mainly of the administration of dihydropyridine L-type calcium channel blockers (e77– e84). These are the only drugs in routine clinical use with demonstrated efficacy in the prevention and treatment of DCI (e77– e84). DCI that arises or persists despite the administration of calcium channel blockers can be treated by induced hypertension with sustained elevation of the systolic blood pressure. Additionally induced hypovolemia, or what has been called triple-H therapy (hypervolemia, hypertension, and hemodilution), yields no further clinical advantage (20, e80).

Long-term complications and clinical outcomes

Approximately 30% of all patients with aneurysmal SAH develop hydrocephalus, reflecting disturbed circulation of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), at some time in the course of their disease and go on to require a permanent CSF diversion procedure. The long-term incidence of a second SAH within 10 years of the first one is 2–3%. One-half of these rebleeds are due to reperfusion and rupture of the treated aneurysm, and the other half to rupture of a new aneurysm (36, 37, e6). Thus, patients should routinely undergo regular follow-up examinations and imaging studies, as there is otherwise no way to assess the risk of rebleeding.

Coiling.

As an alternative to open surgery, a method of endovascular interventional treatment has been developed in which the aneurysm is occluded from within by the placement of platinum spirals (coils) inside it.

Not all patients return to normal everyday living in the aftermath of an acute SAH. Permanent deficits are common (e6). Approximately 30% develop permanent anosmia (e6). Most patients suffer from markedly impaired quality of life over the short term. 60% report personality changes, more than a third complain of increased irritability, and one-quarter complain of emotional lability (e6). One in 14–20 patients develops epilepsy. Overall, only 25% of the patients who are able to resume their previous everyday routine are psychologically and neurologically asymptomatic (e6).

Long-term complications: hydrocephalus.

Some 30% of all patients with aneurysmal SAH develop hydrocephalus, reflecting disturbed circulation of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), at some time in the course of their disease and go on to require a permanent CSF diversion procedure.

Further information on CME.

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Postgraduate and Continuing Medical Education. Deutsches Ärzteblatt provides certified continuing medical education (CME) in accordance with the requirements of the Medical Associations of the German federal states (Länder). CME points of the Medical Associations can be acquired only through the Internet, not by mail or fax, by the use of the German version of the CME questionnaire. See the following website: cme.aerzteblatt.de.

Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit “uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN). The EFN must be entered in the appropriate field in the cme.aerzteblatt.de website under “meine Daten” (“my data”), or upon registration. The EFN appears on each participant’s CME certificate.

This CME unit can be accessed until 25 June 2017, and earlier CME units until the dates indicated:

“ADHD” (Issue 9/2017) until 28 May 2017,

“Pulmonary Hypertension” (Issue 13/2017) until 30 April 2017.

Please answer the following questions to participate in our certified Continuing Medical Education program. Only one answer is possible per question. Please select the most appropriate answer.

Question 1

Which of the following clinical manifestations is typical of subarachnoid hemorrhage?

Neurologic deficits

Intense headaches

Worst headache of life

Unconsciousness

Visual disturbances

Question 2

What type of imaging study is most suitable for the planning of treatment to secure a ruptured aneurysm?

Computed tomography angiography

Digital subtraction angiography

Magnetic resonance angiography

Aortic ultrasonography

Positron emission tomography

Question 3

Drugs of what class are used to prevent and treat vasospasm due to aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage?

Acetylsalicylic acid

Sodium nitroprusside

Antihypertensive drugs

L-type calcium channel blockers

Corticosteroids

Question 4

How sensitive is cranial computed tomography for subarachnoid hemorrhage?

60%

70%

80%

90%

>90%

Question 5

If the diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage is suspected, but computed tomography does not confirm it, what diagnostic measure should be undertaken next?

Analgesia and inpatient observation

Discharge and outpatient referral to a neurologist

Second CT 12 hours later

Magnetic resonance imaging / magnetic resonance angiography

Lumbar puncture

Question 6

How high is the mortality after rebleeding from an unsecured aneurysm?

10–30%

20–40%

30–50%

50–70%

70–90%

Question 7

If computed tomography confirms the diagnosis of a subarachnoid hemorrhage in a patient with a Glasgow coma score of 8, what is the next step?

A cerebrospinal fluid drainage procedure

Laryngeal intubation

Lumbar puncture

Clipping

Coiling

Question 8

A patient with a massive, life-threatening subarachnoid hemorrhage shows signs of impending cerebral herniation. What is the imaging study of choice?

Doppler ultrasonography

Computed tomography (CT)

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

Digital subtraction angiography (DSA)

CT angiography

Question 9

What is the probability that a ruptured, not yet secured aneurysm will rupture a second time within 24 hours of the initial hemorrhage?

7%

15%

30%

40%

50%

Question 10

What is the method of choice for the initial diagnosis of a subarachnoid hemorrhage?

Electroencephalography

MRI

Head CT

DSA

Lumbar puncture

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors state that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Kundra S, Mahendru V, Gupta V, Choudhary AK. Principles of neuroanesthesia in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2014;30:328–337. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.137261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D‘Souza S. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2015;27:222–240. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0000000000000130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molyneux AJ, Kerr RS, Yu LM, et al. International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) of neurosurgical clipping versus endovascular coiling in 2143 patients with ruptured intracranial aneurysms: A randomised comparison of effects on survival, dependency, seizures, rebleeding, subgroups, and aneurysm occlusion. Lancet. 2005;366:809–817. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67214-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Dijk JM, Groen RJ, Ter Laan M, Jeltema JR, Mooij JJ, Metzemaekers JD. Acta Neurochir. Vol. 153. Wien: 2011. Surgical clipping as the preferred treatment for aneurysms of the middle cerebral artery; pp. 2111–2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, Huston J, et al. 3rd Unruptured intracranial aneurysms: Natural history, clinical outcome, and risks of surgical and endovascular treatment. International study of unruptured intracranial aneurysms investigators. Lancet. 2003;362:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13860-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cebral JR, Mut F, Weir J, Putman CM. Association of hemodynamic characteristics and cerebral aneurysm rupture. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32:264–270. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hademenos GJ, Massoud TF, Turjman F, Sayre JW. Anatomical and morphological factors correlating with rupture of intracranial aneurysms in patients referred for endovascular treatment. Neuroradiology. 1998;40:755–760. doi: 10.1007/s002340050679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hassan T, Timofeev EV, Saito T, et al. A proposed parent vessel geometry-based categorization of saccular intracranial aneurysms: Computational flow dynamics analysis of the risk factors for lesion rupture. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:662–680. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.4.0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunt WE, Hess RM. Surgical risk as related to time of intervention in the repair of intracranial aneurysms. J. Neurosurg. 1968;28:14–20. doi: 10.3171/jns.1968.28.1.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen DS, Macdonald RL. Subarachnoid hemorrhage grading scales: a systematic review. Neurocrit Care. 2005;2:110–118. doi: 10.1385/NCC:2:2:110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ujiie H, Tamano Y, Sasaki K, Hori T. Is the aspect ratio a reliable index for predicting the rupture of a saccular aneurysm? Neurosurgery. 2001;48:495–502. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200103000-00007. discussion-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weir B, Amidei C, Kongable G, et al. The aspect ratio (dome/neck) of ruptured and unruptured aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:447–451. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.99.3.0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roman H, Descargues G, Lopes M, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage due to cerebral aneurysmal rupture during pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83:330–334. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-6349.2004.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sriganesh K, Venkataramaiah S. Concerns and challenges during anesthetic management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Saudi J Anaesth. 2015;9:306–313. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.154733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rose MJ. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: An update on the medical complications and treatments strategies seen in these patients. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2011;24:500–507. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0b013e32834ad45b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Gijn J, van Dongen KJ. The time course of aneurysmal haemorrhage on computed tomograms. Neuroradiology. 1982;23:153–156. doi: 10.1007/BF00347559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Martin SC, Teo MK, Young AM, et al. Defending a traditional practice in the modern era: the use of lumbar puncture in the investigation of subarachnoid haemorrhage. Br J Neurosurg. 2015;29:799–803. doi: 10.3109/02688697.2015.1084998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verma RK, Kottke R, Andereggen L, et al. Detecting subarachnoid hemorrhage: Comparison of combined FLAIR/SWI versus CT. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82:1539–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bederson JB, Connolly ES Jr., Batjer HH, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke. 2009;40:994–1025. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.191395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bederson JB, Levy AL, Ding WH, et al. Acute vasoconstriction after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:352–360. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199802000-00091. discussion 60-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sabri M, Jeon H, Ai J, et al. Anterior circulation mouse model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Brain Res. 2009;1295:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dreier JP, Ebert N, Priller J, et al. Products of hemolysis in the subarachnoid space inducing spreading ischemia in the cortex and focal necrosis in rats: A model for delayed ischemic neurological deficits after subarachnoid hemorrhage? J Neurosurg. 2000;93:658–666. doi: 10.3171/jns.2000.93.4.0658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Lieshout JH, Bruland I, Fischer I, et al. Time is life. Increased mortality of patients with aneurysmatic subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by prolonged transport time to a high-volume neurosurgical unit. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.09.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kassell NF, Torner JC, Haley ECJr., Jane JA, Adams HP, Kongable GL. The international cooperative study on the timing of aneurysm surgery. Part 1: Overall management results. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:18–36. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.1.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kassell NF, Torner JC, Jane JA, Haley EC Jr., Adams HP. The international cooperative study on the timing of aneurysm surgery. Part 2: Surgical results. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:37–47. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.73.1.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mahaney KB, Todd MM, Torner JC. INHAST Investigators I: Variation of patient characteristics, management, and outcome with timing of surgery for aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2011;114:1045–1053. doi: 10.3171/2010.11.JNS10795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dandy WE. Intracranial aneurysm of the internal carotid artery: cured by operation. Ann Surg. 1938;107:654–659. doi: 10.1097/00000658-193805000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guglielmi G, Vinuela F, Dion J, Duckwiler G. Electrothrombosis of saccular aneurysms via endovascular approach Part 2: Preliminary clinical experience. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:8–14. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.1.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guglielmi G, Vinuela F, Sepetka I, Macellari V. Electrothrombosis of saccular aneurysms via endovascular approach Part 1: electrochemical basis, technique, and experimental results. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:1–7. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.1.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spetzler RF, McDougall CG, Zabramski JM, et al. The barrow ruptured aneurysm trial: 6-year results. J Neurosurg. 2015;123:609–617. doi: 10.3171/2014.9.JNS141749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Molyneux AJ, Birks J, Clarke A, Sneade M, Kerr RS. The durability of endovascular coiling versus neurosurgical clipping of ruptured cerebral aneurysms: 18 year follow-up of the UK cohort of the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) Lancet. 2015;385:691–697. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60975-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ecker A, Riemenschneider PA. Arteriographic demonstration of spasm of the intracranial arteries, with special reference to saccular arterial aneurysms. J Neurosurg. 1951;8:660–667. doi: 10.3171/jns.1951.8.6.0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vora YY, Suarez-Almazor M, Steinke DE, Martin ML, Findlay JM. Role of transcranial Doppler monitoring in the diagnosis of cerebral vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:1237–1247. discussion 47-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connolly ES Jr., Rabinstein AA, Carhuapoma JR, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2012;43:1711–1737. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182587839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wermer MJ, Greebe P, Algra A, Rinkel GJ. Incidence of recurrent subarachnoid hemorrhage after clipping for ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Stroke. 2005;36:2394–2399. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000185686.28035.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wermer MJ, van der Schaaf IC, Velthuis BK, et al. Follow-up screening after subarachnoid haemorrhage: frequency and determinants of new aneurysms and enlargement of existing aneurysms. Brain. 2005;128:2421–2429. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, Barker-Collo SL, Parag V. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: A systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:355–369. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Passier PE, Visser-Meily JM, Rinkel GJ, Lindeman E, Post MW. Life satisfaction and return to work after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;20:324–329. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Hop JW, Rinkel GJ, Algra A, van Gijn J. Case-fatality rates and functional outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage: A systematic review. Stroke. 1997;28:660–664. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.3.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Stegmayr B, Eriksson M, Asplund K. Declining mortality from subarachnoid hemorrhage: Changes in incidence and case fatality from 1985 through 2000. Stroke. 2004;35:2059–2063. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000138451.07853.b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Lovelock CE, Rinkel GJ, Rothwell PM. Time trends in outcome of subarachnoid hemorrhage: Population-based study and systematic review. Neurology. 2010;74:1494–1501. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181dd42b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Steiger HJ, Beez T, Beseoglu K, Hanggi D, Kamp MA. Perioperative measures to improve outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage-revisiting the concept of secondary brain injury. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2015;120:211–216. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-04981-6_36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E6.van Gijn J, Kerr RS, Rinkeahal GJ. Subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet. 2007;369:306–318. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60153-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E7.Rinkel GJ. Natural history, epidemiology and screening of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Paris: Rev Neurol. 2008;164:781–786. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E8.Rinkel GJ. Medical management of patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Int J Stroke. 2008;3:193–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2008.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E9.Etminan N, Buchholz BA, Dreier R, et al. Cerebral aneurysms: formation, progression, and developmental chronology. Transl Stroke Res. 2014;5:167–173. doi: 10.1007/s12975-013-0294-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E10.Etminan N, Dreier R, Buchholz BA, et al. Age of collagen in intracranial saccular aneurysms. Stroke. 2014;45:1757–1763. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E11.Ali Y, Rahme R, Matar N, et al. Impact of the lunar cycle on the incidence of intracranial aneurysm rupture: Myth or reality? Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110:462–465. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E12.Beck J, Rohde S, Berkefeld J, Seifert V, Raabe A. Size and location of ruptured and unruptured intracranial aneurysms measured by 3-dimensional rotational angiography. Surg Neurol. 2006;65:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.surneu.2005.05.019. discussion -7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E13.Feigin VL. Stroke epidemiology in the developing world. Lancet. 2005;365:2160–2161. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66755-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E14.Feigin VL, Rinkel GJ, Lawes CM, et al. Risk factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage: An updated systematic review of epidemiological studies. Stroke. 2005;36:2773–2780. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000190838.02954.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E15.Matsuda M, Watanabe K, Saito A, Matsumura K, Ichikawa M. Circumstances, activities, and events precipitating aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;16:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E16.Beseoglu K, Hanggi D, Stummer W, Steiger HJ. Dependence of subarachnoid hemorrhage on climate conditions: A systematic meteorological analysis from the Dusseldorf metropolitan area. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:1033–1038. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000325864.91584.c7. discussion 8-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E17.Cowperthwaite MC, Burnett MG. The association between weather and spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage: An analysis of 155 US hospitals. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:132–138. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e3181fe23a1. discussion 8-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E18.Fischer T, Johnsen SP, Pedersen L, Gaist D, Sorensen HT, Rothman KJ. Seasonal variation in hospitalization and case fatality of subarachnoid hemorrhage—a nationwide Danish study on 9,367 patients. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;24:32–37. doi: 10.1159/000081047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E19.Gallerani M, Portaluppi F, Maida G, et al. Circadian and circannual rhythmicity in the occurrence of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1996;27:1793–1797. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.10.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E20.Nyquist PA, Brown RD Jr., Wiebers DO, Crowson CS, O‘Fallon WM. Circadian and seasonal occurrence of subarachnoid and intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2001;56:190–193. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E21.Lahner D, Marhold F, Gruber A, Schramm W. Impact of the lunar cycle on the incidence of aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: myth or reality? Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2009;111:352–353. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2008.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E22.Stienen MN, Smoll NR, Battaglia M, et al. Intracranial aneurysm rupture is predicted by measures of solar activity. World Neurosurg. 2015;83:588–595. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E23.Rosenbaum BP, Weil RJ. Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Relationship to solar activity in the United States, 1988-2010. Astrobiology. 2014;14:568–576. doi: 10.1089/ast.2014.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E24.Naidech AM, Kreiter KT, Janjua N, et al. Cardiac troponin elevation, cardiovascular morbidity, and outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Circulation. 2005;112:2851–2856. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.533620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E25.de Oliveira Manoel AL, Mansur A, Murphy A, et al. Aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage from a neuroimaging perspective. Crit Care. 2014;18 doi: 10.1186/s13054-014-0557-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E26.Byyny RL, Mower WR, Shum N, Gabayan GZ, Fang S, Baraff LJ. Sensitivity of noncontrast cranial computed tomography for the emergency department diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51:697–703. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E27.Perry JJ, Stiell IG, Sivilotti ML, et al. Sensitivity of computed tomography performed within six hours of onset of headache for diagnosis of subarachnoid haemorrhage: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2011;343 doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4277. d4277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E28.Kamp MA, Dibue M, Sommer C, Steiger HJ, Schneider T, Hanggi D. Evaluation of a murine single-blood-injection SAH model. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114946. e114946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E29.Bederson JB, Germano IM, Guarino L. Cortical blood flow and cerebral perfusion pressure in a new noncraniotomy model of subarachnoid hemorrhage in the rat. Stroke. 1995;26:1086–1091. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.6.1086. discussion 91-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E30.Trojanowski T. Acta Neurochir. Vol. 62. Wien: 1982. Experimental subarachnoid haemorrhage Part I: A new approach to subarachnoid blood injection in cats; pp. 171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E31.Trojanowski T. Acta Neurochir. Vol. 64. Wien: 1982. Experimental subarachnoid haemorrhage Part II: Extravasation volume and dynamics of subarachnoid arterial bleeding in cats; pp. 103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E32.Voldby B. Pathophysiology of subarachnoid haemorrhage. Experimental and clinical data. Wien: Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1988;45:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E33.Westermaier T, Jauss A, Eriskat J, Kunze E, Roosen K. Acute vasoconstriction: Decrease and recovery of cerebral blood flow after various intensities of experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. J Neurosurg. 2009;110:996–1002. doi: 10.3171/2008.8.JNS08591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E34.Westermaier T, Jauss A, Eriskat J, Kunze E, Roosen K. Time-course of cerebral perfusion and tissue oxygenation in the first 6 h after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29:771–779. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E35.Schubert GA, Seiz M, Hegewald AA, Manville J, Thome C. Acute hypoperfusion immediately after subarachnoid hemorrhage: A xenon contrast-enhanced CT study. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26:2225–2231. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.0924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E36.van der Schaaf I, Wermer MJ, van der Graaf Y, Hoff RG, Rinkel GJ, Velthuis BK. CT after subarachnoid hemorrhage: Relation of cerebral perfusion to delayed cerebral ischemia. Neurology. 2006;66:1533–1538. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000216272.67895.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E37.Sanelli PC, Jou A, Gold R, et al. Using CT perfusion during the early baseline period in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage to assess for development of vasospasm. Neuroradiology. 2011;53:425–434. doi: 10.1007/s00234-010-0752-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E38.Kamp MA, Heiroth HJ, Beseoglu K, Turowski B, Steiger HJ, Hanggi D. Early CT perfusion measurement after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A screening method to predict outcome? Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2012;114:329–332. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0956-4_63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E39.Etminan N, Beseoglu K, Heiroth HJ, Turowski B, Steiger HJ, Hanggi D. Early perfusion computerized tomography imaging as a radiographic surrogate for delayed cerebral ischemia and functional outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2013;44:1260–1266. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.675975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E40.Honda M, Sase S, Yokota K, et al. Neurol Med Chir. Vol. 52. Tokyo: 2012. Early cerebral circulatory disturbance in patients suffering subarachnoid hemorrhage prior to the delayed cerebral vasospasm stage: Xenon computed tomography and perfusion computed tomography study; pp. 488–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E41.Tsuang FY, Chen JY, Lee CW, et al. Risk profile of patients with poor-grade aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage using early perfusion computed tomography. World Neurosurg. 2012;78:455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E42.Tateyama K, Kobayashi S, Murai Y, Teramoto A. Assessment of cerebral circulation in the acute phase of subarachnoid hemorrhage using perfusion computed tomography. J Nippon Med Sch. 2013;80:110–118. doi: 10.1272/jnms.80.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E43.Keep RF, Andjelkovic AV, Stamatovic SM, Shakui P, Ennis SR. Ischemia-induced endothelial cell dysfunction. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2005;95:399–402. doi: 10.1007/3-211-32318-x_81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E44.Friedrich V, Flores R, Sehba FA. Cell death starts early after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosci Lett. 2012;512:6–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E45.Iuliano BA, Pluta RM, Jung C, Oldfield EH. Endothelial dysfunction in a primate model of cerebral vasospasm. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:287–294. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.100.2.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E46.Jung CS, Iuliano BA, Harvey-White J, Espey MG, Oldfield EH, Pluta RM. Association between cerebrospinal fluid levels of asymmetric dimethyl-L-arginine, an endogenous inhibitor of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, and cerebral vasospasm in a primate model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:836–842. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.101.5.0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E47.Akpinar G, Acikgoz B, Surucu S, Celik HH, Cagavi F. Ultrastructural changes in the circumventricular organs after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurol Res. 2005;27:580–585. doi: 10.1179/016164105X48752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E48.Cahill J, Calvert JW, Solaroglu I, Zhang JH. Vasospasm and p53-induced apoptosis in an experimental model of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2006;37:1868–1874. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000226995.27230.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E49.Cahill J, Calvert JW, Zhang JH. Mechanisms of early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:1341–1353. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E50.Matz PG, Fujimura M, Lewen A, Morita-Fujimura Y, Chan PH. Increased cytochrome c-mediated DNA fragmentation and cell death in manganese-superoxide dismutase-deficient mice after exposure to subarachnoid hemolysate. Stroke. 2001;32:506–515. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.2.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E51.Prunell GF, Svendgaard NA, Alkass K, Mathiesen T. Delayed cell death related to acute cerebral blood flow changes following subarachnoid hemorrhage in the rat brain. J Neurosurg. 2005;102:1046–1054. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.6.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E52.Zubkov AY, Tibbs RE, Clower B, Ogihara K, Aoki K, Zhang JH. Morphological changes of cerebral arteries in a canine double hemorrhage model. Neurosci Lett. 2002;326:137–141. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E53.Park S, Yamaguchi M, Zhou C, Calvert JW, Tang J, Zhang JH. Neurovascular protection reduces early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2004;35:2412–2417. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000141162.29864.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E54.Yatsushige H, Ostrowski RP, Tsubokawa T, Colohan A, Zhang JH. Role of c-jun N-terminal kinase in early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1436–1448. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E55.Prunell GF, Svendgaard NA, Alkass K, Mathiesen T. Inflammation in the brain after experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:1082–1092. discussion -92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E56.Schneider UC, Davids AM, Brandenburg S, et al. Microglia inflict delayed brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neuropathol. 2015;130:215–231. doi: 10.1007/s00401-015-1440-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E57.Sehba FA, Hou J, Pluta RM, Zhang JH. The importance of early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Prog Neurobiol. 2012;97:14–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E58.Machi P, Lobotesis K, Vendrell JF, et al. Endovascular therapeutic strategies in ruptured intracranial aneurysms. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82:1646–1652. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E59.Ohta H, Ito Z. [Cerebral infraction due to vasospasm, revealed by computed tomography (author‘s transl)] Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 1981;21:365–372. doi: 10.2176/nmc.21.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E60.Roos YB, de Haan RJ, Beenen LF, Groen RJ, Albrecht KW, Vermeulen M. Complications and outcome in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: A prospective hospital based cohort study in the Netherlands. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:337–341. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.3.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E61.Dorhout Mees SM, Kerr RS, Rinkel GJ, Algra A, Molyneux AJ. Occurrence and impact of delayed cerebral ischemia after coiling and after clipping in the International Subarachnoid Aneurysm Trial (ISAT) J Neurol. 2012;259:679–683. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-6243-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E62.Dorsch N. A clinical review of cerebral vasospasm and delayed ischaemia following aneurysm rupture. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2011;110:5–6. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-0353-1_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E63.Beseoglu K, Pannes S, Steiger HJ, Hanggi D. cta Neurochir. Vol. 152. Wien: 2010. Long-term outcome and quality of life after nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage; pp. 409–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E64.Beseoglu K, Holtkamp K, Steiger HJ, Hanggi D. Fatal aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: Causes of 30-day in-hospital case fatalities in a large single-centre historical patient cohort. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E65.Dehdashti AR, Mermillod B, Rufenacht DA, Reverdin A, de Tribolet N. Does treatment modality of intracranial ruptured aneurysms influence the incidence of cerebral vasospasm and clinical outcome? Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;17:53–60. doi: 10.1159/000073898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E66.Fisher CM, Kistler JP, Davis JM. Relation of cerebral vasospasm to subarachnoid hemorrhage visualized by computerized tomographic scanning. Neurosurgery. 1980;6:1–9. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198001000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E67.Beseoglu K, Unfrau K, Steiger HJ, Hanggi D. Influence of blood pressure variability on short-term outcome in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2010;71:69–74. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1237725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E68.Beseoglu K, Etminan N, Steiger HJ, Hanggi D. The relation of early hypernatremia with clinical outcome in patients suffering from aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;123:164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E69.de Rooij NK, Rinkel GJ, Dankbaar JW, Frijns CJ. Delayed cerebral ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage: a systematic review of clinical, laboratory, and radiological predictors. Stroke. 2013;44:43–54. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.674291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E70.Diringer MN, Bleck TP, Claude Hemphill J, et al. 3rd Critical care management of patients following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage recommendations from the neurocritical care society‘s multidisciplinary consensus conference. Neurocrit Care. 2011;15:211–240. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9605-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E71.Washington CW, Zipfel GJ. Participants in the international multi-disciplinary consensus conference on the critical care management of subarachnoid H: Detection and monitoring of vasospasm and delayed cerebral ischemia: A review and assessment of the literature. Neurocrit Care. 2011;15:312–317. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9594-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E72.Hanggi D, Eicker S, Beseoglu K, Behr J, Turowski B, Steiger HJ. A multimodal concept in patients after severe aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: Results of a controlled single centre prospective randomized multimodal phase I/II trial on cerebral vasospasm. Cent Eur Neurosurg. 2009;70:61–67. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1087214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E73.Turowski B, Haenggi D, Wittsack HJ, Beck A, Aurich V. [Computerized analysis of brain perfusion parameter images] Rofo. 2007;179:525–529. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-962853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E74.Turowski B, Haenggi D, Wittsack J, Beck A, Moedder U. [Cerebral perfusion computerized tomography in vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage: Diagnostic value of MTT] Rofo. 2007;179:847–854. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-963197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E75.Dankbaar JW, de Rooij NK, Rijsdijk M, et al. Diagnostic threshold values of cerebral perfusion measured with computed tomography for delayed cerebral ischemia after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2010;41:1927–1932. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.574392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E76.Caspers J, Rubbert C, Turowski B, et al. Timing of mean transit time maximization is associated with neurological outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Clin Neuroradiol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00062-015-0399-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E77.Macdonald RL. Origins of the concept of vasospasm. Stroke. 2016;47:e11–e15. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E78.Dorhout Mees SM, Rinkel GJ, Feigin VL, et al. Calcium antagonists for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Database Syst Rev. 2007 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000277.pub3. CD000277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E79.Vergouwen MD, Etminan N, Ilodigwe D, Macdonald RL. Lower incidence of cerebral infarction correlates with improved functional outcome after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:1545–1553. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E80.Vergouwen MD. Vasospasm versus delayed cerebral ischemia as an outcome event in clinical trials and observational studies. Neurocrit Care. 2011;15:308–311. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9586-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E81.Vergouwen MD, Vermeulen M, Coert BA, Stroes ES, Roos YB. Microthrombosis after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: An additional explanation for delayed cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1761–1770. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E82.Hanggi D, Perrin J, Eicker S, et al. Local delivery of nimodipine by prolonged-release microparticles-feasibility, effectiveness and dose-finding in experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042597. e42597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E83.Hanggi D, Etminan N, Macdonald RL, et al. NEWTON: Nimodipine microparticles to enhance recovery while reducing toxicity after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2015;23:274–284. doi: 10.1007/s12028-015-0112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E84.Suarez JI. Magnesium sulfate administration in subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2011;15:302–307. doi: 10.1007/s12028-011-9603-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]