Abstract

Purpose

Women in alcohol treatment are more likely to relapse when in unpleasant, negative emotional states. Given the demonstrated benefits of exercise for decreasing depression, negative affect, and urges to drink, helping women engage in a lifestyle physical activity (LPA) intervention in early recovery may provide them a tool they can utilize “in the moment” in order to cope with negative emotional states and alcohol craving when relapse risk is highest. New digital fitness technologies (e.g., Fitbit activity monitor with web and mobile applications) may facilitate increases in physical activity (PA) through goal setting and self-monitoring.

Method

We piloted a 12-week LPA+Fitbit intervention focused on strategically using bouts of PA to cope with affect and alcohol cravings to prevent relapse in 20 depressed women (mean age=39.5 years) in alcohol treatment.

Results

Participants wore their Fitbit on 73% of days during the intervention period. An average of 9,174 steps/day were taken on the days the Fitbit was worn. Participants completed 4.7 of the 6 scheduled phone PA counseling sessions (78%). Among women who completed the intervention (n=15), 44% remained abstinent throughout the entire course of treatment. On average, women were abstinent on 95% of days during the 12-week intervention. Participants reported an increase in using PA to cope with either negative affect or urges to drink from baseline to end of treatment (p<.05). Further, participants reported high satisfaction with the LPA+Fitbit intervention and with the Fitbit tracker.

Conclusions

Further research is needed to evaluate the LPA+Fitbit intervention in a more rigorous randomized controlled trial. If the LPA+Fitbit intervention proves to be helpful during early recovery, this simple, low-cost and easily transported intervention can provide a much-needed alternate coping strategy to help reduce relapse risk among women in alcohol treatment.

Keywords: Alcohol Use Disorders, Physical Activity, Relapse Prevention, Coping, Women

1. Introduction

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are a significant and costly public health problem. AUDs are the third leading preventable cause of death in the U.S.(Mokdad, Marks, Stroup, & Gerberding, 2004) and produce a heavy economic burden in terms of health care costs, crime, and lost work productivity (Rehm et al., 2009). While certain behavioral and pharmacological treatments for AUDs have been demonstrated to be efficacious in helping individuals achieve an initial period of abstinence, relapse rates in the first year following treatment are extremely high, typically ranging from 60 - 95% (Anton et al., 2006; Brandon, Vidrine, & Litvin, 2007; Project Match Research Group, 1997; Xie, McHugo, Fox, & Drake, 2005). In particular, the first 3 months of sobriety pose the greatest risk for relapse, and the greatest challenge for intervention efforts (Hendershot, Witkiewitz, George, & Marlatt, 2011; Marlatt & Donovan, 2005). Therefore, intervention approaches to decrease relapse risk during that period are critically needed.

Although men are twice as likely to develop an AUD, women are more vulnerable to the negative health consequences of AUDs and have significantly more medical problems than men (Schenker, 1997). Women with AUDs also have higher rates of psychiatric comorbidity, particularly depression (Cornelius et al., 1995; Hartka et al., 1991; Kessler et al., 1997), which has been found to be associated with poorer coping strategies in treatment seeking AUD patients (Sanchez et al., 2014) as well as increased risk for relapse (Gamble et al.,2013). Indeed, women with AUDs are much more likely than men to state that they drink to cope with or “self-medicate” negative affect associated with stressors or depression (Brienza & Stein, 2002; Lehavot, Stappenbeck, Luterek, Kaysen, & Simpson, 2014). These gender differences in drinking motives also translate to differences in predictors of relapse. For example, while women may be just as likely to relapse following alcohol treatment as men, they are much more likely to do so because of poor coping strategies, negative mood, and lower self-efficacy for abstinence (Walitzer & Dearing, 2006). Therefore, depression and negative affective states are highly prevalent among women with AUDs and play an important role both in why women drink and relapse.

In addition, AUDs are more stigmatizing for women than men, and shame and guilt experienced by women with AUDs are barriers to receiving and completing addiction treatment(Brady & Ashley, 2005). Women in addiction treatment are more likely to have children under the age of 18 than men (75% vs 50%) and having children is related to lower likelihood of completing treatment (Brady & Ashley, 2005). Indeed, more so than in men, familial responsibilities interfere with women’s ability to attend regular treatment sessions (Brady & Ashley, 2005). Therefore, easily accessible and feasible strategies are necessary to support women in early recovery from alcohol.

Helping women increase their physical activity during early recovery may be one such strategy. Physical activity may serve as a coping strategy for managing depression, negative affect, and alcohol craving during early recovery among alcohol dependent women. An growing body of literature demonstrates the effect of increasing physical activity on reducing depressive symptoms (Kvam et al., 2016; Wegner et al., 2014). Similarly, negative affective states improve after acute bouts of exercise (Bernstein & McNally, 2016; Ensari, Greenlee, Motl, & Petruzzello, 2015; Reed & Buck, 2009), including alcohol craving among alcohol dependent patients (Brown, Prince, Minami, & Abrantes, 2016; Ussher, Sampuran, Doshi, West, & Drummond, 2004). For example, even a brief, 10-minute bout of moderate-intensity cycling decreased urges to drink among men and women recently detoxed from alcohol (Ussher et al., 2004). In community samples, exercise is often identified as a coping strategy for stress – particularly among women – and is inversely related to utilizing drinking to cope with stress (Cairney, Kwan, Veldhuizen, & Faulkner, 2013). While the idea of strategically utilizing bouts of activity to cope with negative affect and craving is still relatively unexplored, one previous study (Linke et al., 2012) has successfully implemented this approach with smokers undergoing a cessation attempt. As such, an intervention that helps depressed alcohol dependent women learn to utilize bouts of physical activity (e.g., done “in-the-moment” for as little as 10 minutes) to manage negative affect and alcohol cravings could potentially decrease relapse risk.

While an impressive body of work exists for the benefit of exercise for mental health outcomes, the examination of exercise for substance use problems has lagged considerably behind (Abrantes, Matsko, Wolfe, & Brown, 2013). The few existing studies that have reported alcohol use outcomes have shown promising results (Brown et al., 2014; T. J. Murphy, Pagano, & Marlatt, 1986; Sinyor, Brown, Rostant, & Seraganian, 1982). However, these studies included few women and primarily used in-person, supervised, gym-based approaches. Given that these types of programs are associated with a number of barriers such as cost, weather, work and personal commitments, and limited free time (Salmon, Owen, Crawford, Bauman, & Sallis, 2003), they may pose challenges for women in early recovery from alcohol. On the other hand, lifestyle physical activity (LPA) interventions, an alternative to supervised, structured exercise programs, encourage the daily accumulation of self-selected activities, planned or unplanned, that can be integrated into every day life(Dunn et al., 1999). The most common physical activity promoted by LPA programs, and the one most frequently selected by study participants, is brisk walking (Croteau, 2004). Not only can walking be easily integrated into individuals’ daily routines, it has also been associated with improved cardiorespiratory fitness and health outcomes (M. H. Murphy, Nevill, Murtagh, & Holder, 2007) including decreased depressive symptoms (Robertson, Robertson, Jepson, & Maxwell, 2012), and negative affect, even with brief 10-minute walks (Ekkekakis, Hall, VanLanduyt, & Petruzzello, 2000). Though potentially a good fit for meeting the unique needs of women in alcohol treatment, LPA interventions have thus far not been examined for this population.

Given the intermittent physical activity involved in LPA interventions, activity monitors (e.g., pedometers or other devices) have often been included to help facilitate self-monitoring and goal-setting. Indeed, pedometers are considered acceptable and highly useful for setting goals(Heesch, Dinger, McClary, & Rice, 2005; Lauzon, Chan, Myers, & Tudor-Locke, 2008; Catrine Tudor-Locke & Lutes, 2009). Participants report, through the visual feedback from the pedometer, experiencing an immediate awareness of PA levels, which helps to facilitate changes in PA behavior (Catrine Tudor-Locke & Lutes, 2009). Use of activity monitors in the context of LPA interventions, have also been associated with increased likelihood of meeting public health recommendation levels of physical activity (Merom et al., 2007). With recent advances in sensor and Bluetooth technologies, new types of activity monitors have emerged and are currently commercially available (e.g., Fitbit). Many of these activity monitors also have websites that allow the user to self-monitor and interact with their physical activity data (e.g., set step count goals, recognition for achieving goals) as well as applications for mobile devices. Market group research surveys have found that more women than men are interested in purchasing these activity trackers and find that tracking step counts is one of the most desirable features for women (mobihealthnews, 2014). While commercially popular, little research has examined these new and increasingly used technologies. However, several studies have been published demonstrating the validity of the Fitbit activity monitor (Adam Noah, Spierer, Gu, & Bronner, 2013; Fulk et al., 2014; Lee, Kim, & Welk, 2014). Therefore, newer activity monitors, such as the Fitbit, can be utilized in the context of LPA interventions in the same manner as pedometers while incorporating technologies that greatly facilitate self-monitoring and goal-setting, which are essential for initiating and maintaining physical activity in the long-term (Nigg, Borrelli, Maddock, & Dishman, 2008).

The purpose of this study was to develop a lifestyle physical activity intervention that was supported by the use of the Fitbit physical activity tracker, and its mobile and web-based platforms (LPA+Fitbit), for depressed, alcohol dependent women in alcohol treatment. In addition to the describing the treatment development process, we present information on the feasibility and acceptability of the LPA+Fitbit intervention as well as preliminary outcomes related to drinking, physical activity, depressive symptoms, and exercise to cope behaviors.

2. Method

2.1 Participants

Between March 2016 and September 2016, a total of 53 women who were current patients in an alcohol and drug partial (ADP) hospitalization program were screened for study eligibility. Eligibility criteria included: (a) female, (b) between 18 and 65 years of age, (c) engaged in alcohol treatment in the ADP program, (d) elevated depressive symptoms (score of 5 or above on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001) (d) inactive or low active (i.e., less than 150 minutes/week of moderate-intensity exercise for the past 6 months), (e) access to a computer connected to the internet or a smartphone compatible with the Fitbit application. Exclusion criteria included (a) current DSM-5 diagnosis moderate/severe substance use disorder (other than alcohol use disorder), anorexia, or bulimia (b) history of psychotic disorder or current psychotic symptoms (c) current suicidality or homicidality, (d) current mania (e) physical or medical problems that would not allow safe participation in a program of moderate intensity physical activity (i.e., not medically cleared by study physician), and (f) current pregnancy or intent to become pregnant during the next 12 weeks.

The ADP program is a 5–10 day alcohol and drug treatment program that runs Monday through Friday from 9:00am to 3:30pm. ADP is an abstinence-based, relapse prevention program focused on increasing cognitive-behavioral skills for sobriety. Patients participate in daily group and individual therapy, receive medication management, and are discharged with aftercare plans in place. Patients transfer to ADP directly from inpatient detoxification program or are self-referred from the community. Therefore, patients average any where from 2–7 days of sobriety by the time of admission. Potential participants were approached about study participation on either their first or second day of the program. While length of stay is dependent on many factors including insurance coverage, relapse during program, and employment status, no women were excluded from participation due to length of stay.

Thirteen women did not meet eligibility criteria for the following reasons: lack of internet access (n=3), did not meet depression threshold (n=5), diagnosed with a moderate or severe substance use disorder (n=3), medical rule-out (n=1), or were diagnosed with a manic episode in the previous 6 months (n=1). Additionally, 17 women declined to participate and 3 women dropped out of ADP prior to study recruitment, leaving a total of 20 participants who were fully eligible and enrolled in the study.

2.2 Recruitment

Patients’ medical records were reviewed to help identify potentially eligible participants. Participants who appeared to meet study criteria were provided with brief information about the study. Interested participants underwent a brief screen (5–10 minutes) to determine physical activity and depression inclusion criteria. Eligibility was confirmed with a more comprehensive baseline assessment. Participants were medically cleared by the study physician to engage in a program of moderate-intensity exercise and engaged in a cycle fitness test (see below for details). After these baseline procedures and prior to partial hospital discharge, the participant was scheduled for an in-person orientation session with a study physical activity counselor.

2.3 End of Treatment Assessment

At the end of the 12-week intervention, participants were scheduled for an in-person assessment at which time they completed questionnaires and participated in a semi-structured qualitative exit interview. The interview was used to collect further information regarding the perceived usefulness and applicability of the various intervention components.

2.4 Intervention

The LPA+Fitbit intervention consists of the following components:

2.4.1. In-Person LPA+Fitbit Orientation Session

While still a patient in the ADP program, enrolled study participants met with a physical activity counselor for an hour-long orientation session. The physical activity counselor provided information on the acute and long-term psychological and physical benefits of increasing physical activity. Counselors introduced to the concept of utilizing brief bouts of physical activity as a coping strategy for managing difficult emotions or alcohol cravings “in-the-moment.” The counselor engaged the participant in a discussion of various strategies for including physical activity in their lives. The counselor gave participants lists of free/lost cost resources to help them select activities that can be done inside (e.g., walk-at-home DVDs), outside (e.g., bike paths), irrespective of weather (e.g., mall walking), and that are easily integrated into daily life (e.g., walking dog; grocery shopping; using stairs rather than elevators; walking in place while watching TV/listening to music). Counselors then oriented participants to the proper use of the Fitbit activity tracker, offering tips for self-monitoring step counts, duration and frequency of physical activity goals. Lastly, participants were given a starting step-count goal of 4,500 steps/day with a plan for increasing steps/day by 500 steps each week of the intervention.

2.4.2. Telephone PA Counseling Sessions

After participants were discharged from the Partial Hospitalization Alcohol and Drug Treatment Program, the study counselor called participants at weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 of the intervention for a 30-minute telephone session to: a) review PA progress and re-evaluate current step-count goals, b) problem-solve any barriers to incorporating physical activity into their daily lives, c) address any difficulties utilizing the Fitbit tracker, (d) discuss and encourage the use of bouts of PA as a coping strategy, and e) engage the participant in a brief topic discussion focused on increasing and maintaining physical activity. The study counselor reinforced participants for wearing the Fitbit and praised efforts toward increasing physical activity during the prior week(s) as well as provided encouragement for continued engagement in the intervention. Participants were asked about whether the prior step goal(s) felt appropriate, too easy, or too challenging. If women reported difficulty meeting goals, the subsequent goal would not be increased, but remained the same, with emphasis placed on identifying barriers to increased physical activity. In addition, the counselor engaged participants in a discussion of various PA counseling topics adapted from prior work (Brown et al., 2009) including: Session 1 (week 1) – Learning to use bouts of PA to cope with negative emotions and alcohol cravings, Session 2 (week 2) – How to get motivated; Session 3 (week 4) – Learning to set goals and seeking support from others; Session 4 (week 6) -- Identifying and overcoming barriers to PA; Session 5 (week 8) -- How to get back on track when a lapse in PA occurs; and Session 6 (week 10) – How to maintain PA long-term.

2.4.3. Fitbit Activity Tracker

Most participants (70%) received the Fitbit Charge. However, due to Fitbit’s discontinuation of this monitor during the course of the study and our own experiences with battery issues, the last few participants recruited for the study (30%) received the Fitbit Alta. The Fitbit Alta, though an updated version of the Charge, is a similar, wrist-worn activity monitor that provided the same measurements and visual feedback to the participants as the Charge. A study-generated Fitbit account (on Fitbit.com) and password were created for each participant. With the participant’s permission, the investigators had access to the participant’s activity data throughout the course of the intervention. Counselors monitored and provided feedback on the participant’s physical activity during the PA telephone sessions. Participants were instructed to self-monitor physical activity in 3 ways: 1) looking at the data displayed on the Fitbit device itself, 2) checking their Bluetooth-enabled smartphone/tablet Fitbit application, and 3) by logging in to Fitbit.com on any internet-enabled computer (Fitbit provides a small USB device that allows for wireless data transfer from the activity tracker to one’s computer). Research staff customized each participant’s accounts to display the following: daily steps, distance travelled, very active minutes, activity during each hour of the day, and badges earned. Fitbit displays physical activity data utilizing a color-coded scheme (i.e., blue for getting started, red for low levels of activity, yellow for almost reaching your goals, and green for achieving daily goals). In addition, other features such as smiley faces that appear when daily goals are achieved and badges awarded for specific accomplishments (e.g., reaching a distance or step-count milestone) could be reinforcing and motivating for participants. While the display on the Fitbit tracker provided data for the day it was being worn, the Fitbit website also provided data over the course of previous weeks and months. Given that most sedentary individuals accumulate 3,000–4,000 steps per day (Tudor-locke et al., 2011), participants were given the goal of achieving 4,500 steps/day at week 1 and increasing each week of the intervention by 500 steps/day (about ¼ mile increase). This increase in steps would eventually result in most participants achieving an average of 10,000 steps a day by the end of the intervention, which is equivalent to the American College of Sports Medicine’s (ACSM) current recommendations for physical activity (Tudor-Locke et al., 2004).

2.5 Measures

2.5.1 Psychiatric Comorbidity

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5) (First, 2014) was utilized at baseline to evaluate psychiatric comorbidity. Specifically, we administered the alcohol and drug use disorder, depressive disorder, psychotic disorder, and eating disorder modules.

2.5.2 Alcohol Use

The Timeline Followback (TLFB) (Sobell & Sobell, 1992) was administered at baseline and end of treatment to assess for quantity and frequency of alcohol use over the previous 90 days. The TLFB uses anchor dates to prompt participant recall. With data from the TLFB, we calculated several indices of alcohol use for our analyses: days of alcohol use, percent days abstinent, and drinks per drinking day.

2.5.3 Physical Activity

Physical activity was measured in several ways: step counts, minutes of physical activity, and episodes of using physical activity to cope.

We measured self-reported physical activity using the Timeline Followback for Exercise (Panza, Weinstock, Ash, & Pescatello, 2012). The psychometric properties of the TLFB-E include: criterion validity (r=.35 to r=.39), convergent validity (r=.65 to r=.80), and test-retest reliability (r=.79 to r=.97). During the Timeline Followback (TLFB), participants were also asked to indicate what days, of the previous 90, they engaged in any exercise of at least 10 minutes in duration. Additionally, they were asked to rate the duration and rate of perceived exertion (RPE; Borg, 1970) of physical activity on a scale of 6–20 with the following anchors: 6= no exertion at all, 9=very light, 11=light, 13=somewhat hard, 15=hard, 19=extremely hard, and 20=maximal exertion. RPE ratings of 12 and above are considered moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA) (Ritchie, 2012). Subsequently, we created two variables: average minutes per week of all PA and average minutes per week of MVPA (i.e., only activity that was rated at least 12 and above on the RPE scale).

We calculated an estimate of baseline step counts utilizing their self-reported levels of PA. The all PA variable was converted to steps/day by assuming that 3,500 steps are taken every 30 minutes during physical activity (Tudor-locke et al., 2011). Then we added these estimated steps to the 4,000 steps per day average taken by a sedentary individual (Tudor-locke et al., 2011; Tudor-Locke & Bassett, 2004) to create a conservative estimate of baseline steps/day.

Step counts were measured during the course of the 12-week intervention objectively via the Fitbit. Step counts were downloaded from the Fitbit web server. Only days which participants wore their Fitbit at least 8 hours were used for step count totals. An average daily step count was calculated for participants who had at least 8 weeks of data (n=17).

In addition, for each day on the TLFB where they indicated they exercised, participants were asked to report whether they had done so as a means to cope with either negative affect for alcohol cravings.

2.5.4 Depressive Symptoms

To more accurately assess depression, we included both a clinician-rated and self-report measure of depression symptomatology. The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS) (Rush et al., 2003) is a clinician-rated measure of depression severity. Sixteen items assess for various symptoms of depression. Items are rated on a scale of 0 (symptom absent) to 3 (Cronbach’s alpha =.80 at baseline, .76 at end of treatment (EOT)). Additionally, responses from Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., 2001) were used as a self-report measure of depression symptomatology. Participants answered on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) the frequency in which they experienced 9 symptoms of depression over the previous 2 weeks (Cronbach’s alpha = .76 at baseline, .93 at EOT).

2.5.5 Anxiety Symptoms

The GAD-7 (Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Lo, 2017) was utilized as a measure of generalized anxiety disorder symptomatology. The GAD-7 asks participants to rate how often over the last two weeks that they have experienced seven symptoms of anxiety on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day) (alpha=.93 at baseline, .97 at EOT).

2.5.6 Affect

The PANAS (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) was administered at baseline and each subsequent follow-up assessment timepoint. The PANAS is comprised of two subscales, which correspond to positive affect and negative affect. Ten items comprise the negative affect scale (alpha reliability = 0.87 at baseline, 0.97 at EOT), and ten items are in the positive affect scale (alpha = 0.92 at baseline, 0.96 at EOT).

2.5.7 Alcohol craving

The Penn Alcohol Craving Scale (PACS) (Flannery, Volpicelli, & Pettinati, 1999) is a 5-item measure designed to assess for recent craving. Participants are asked to rate their experience over the past week on a scale of 0 (low) to 6 (high). Alpha reliability coefficients were excellent (alpha=0.93 at baseline, =0.98 at end of treatment).

2.5.8 Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Body Composition

Cardiorespiratory fitness was assessed with the 6-minute Astrand-Ryhming fitness cycle ergometer testing protocol (Brubaker, Otto, & Whaley, 2006). After a brief warm-up period (~2–3 minutes), the exercise physiologist adjusted the power output on the ergometer to emit a heart rate of 125–170 bpm. Participants cycled at a fixed pace of 50 revolutions/min. Heart rate and blood pressure were monitored during the test. Gender, weight, steady-state heart rate, workload, and an age-correction factor were used to estimate participants’ VO2max (Brubaker et al., 2006). During this testing session, participants’ weight and height (to calculate body mass index (BMI)), percent body fat, and waist circumference were obtained.

2.5.9 Intervention Satisfaction and Acceptability

Participants completed the 8-item Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ; Attkisson and Zwick, 1982) and answered questions on the overall acceptability and satisfaction with the LPA+Fitbit intervention. Questions were on a 4-point Likert scale, with higher numbers reflecting greater satisfaction. An additional question was included regarding the extent to which they thought participating in the LPA+Fitbit program helped their recovery from alcohol. Further, participants were asked to rate their experience with the Fitbit tracker using the 19-item Participant Experience Questionnaire of Wearable Activity Trackers (PEQ; Mercer et al., 2016), with items rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree. Lastly, at EOT, participants completed a qualitative exit interview with a study clinician who was not their primary counselor. Participants were asked about their general impressions of the LPA+Fitbit intervention, from which feasibility and acceptability were determined.

2.6 Data Analysis plan

We present descriptive statistics for participant characteristics at baseline, including demographic information, self-reported alcohol use, PA, depression, anxiety, and affect. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between participants who completed the end of treatment assessments and those who did not utilizing an analysis of variance (ANOVA). In addition, with linear regression analysis, these same variables will be examined as predictors of telephone session attendance during the intervention. Then, descriptive statistics evaluating participants’ perceptions of acceptability and feasibility are presented. Changes in main outcome variables of the intervention (PA outcomes, alcohol use, depression, anxiety, and affect and cardiorespiratory fitness/body composition) are then evaluated using paired samples t-tests. Given that preliminary nature of the study and small sample size, in addition to examining statistical significance, we also calculate effect sizes (Leon, Davis, & Kraemer, 2011) in the form of Cohen’s dz (Cohen, 1988), which corrects for the dependence between samples by accounting for the correlation between variables (Lakens, 2013). To address missing data, we conducted analyses in two ways: using only treatment completers (n=15) and intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses using all participants (n=20). For the analyses using all participants, we carry forward baseline values as a worst case analysis (Myers, 2000), thus assuming that missing data were due to relapse an individual’s scores on variables of interest (i.e., alcohol use variables, affect, physical activity) would be similar to their pre-treatment levels. We excluded one participant from step count analyses due to data quality. We evaluated correlations between PA (as all activity and MVPA) and changes in depression, anxiety, affect, and craving from baseline to EOT. The first and second author read the transcribed qualitative interviews conducted at EOT and identified several themes that emerged from these discussions.

3. Results

3.1 Participant Characteristics

Participants (N=20) ranged in age from 22 to 61, with a mean age of 39.5 (SD=10.6). The sample was primarily Caucasian (85%) and non-Latino (90%). Most women held a college degree or higher (55.0%) and 65% were employed at least part-time. Women were enrolled in the ADP program for an average of 8.45 days (SD=2.72). The majority of women met SCID-5 diagnostic criteria for current Major Depressive Disorder (55.0%) and participants had an average score of 8.74 (SD=4.98) on the QIDS. Almost half of participants (n=9, 45%) reported engaging in no exercise (defined as 10 minutes or more of moderate or vigorous physical activity) at baseline. At baseline, participants consumed alcohol an average of 50.2 (SD=26.13) of the prior 90 days (52.6%) and reported consuming 10.11 (SD=6.36) drinks per drinking day.

After ADP discharge, 64.3% of participants pursued aftercare services with 50% engaging in individual therapy and 21.4% participated in group therapy. Two women were readmitted for alcohol detoxification after relapsing. More than half of women (57.1%) reported participating in 12-step meetings. End of treatment assessments were conducted on 75% of participants. ANOVA analyses revealed that there were no baseline differences in demographic variables, PA levels, alcohol use, depression, affect between women who completed versus did not complete the end of treatment assessments.

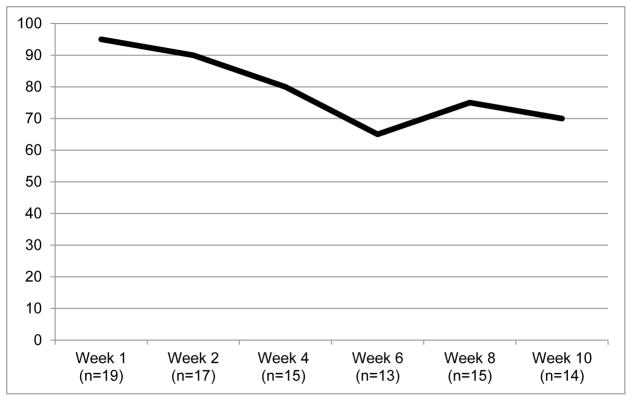

3.2 Attendance at PA Treatment Sessions

Figure 1 displays attendance at the physical activity counseling sessions. Participants attended 78% of PA counseling sessions (4.7 out of 6 sessions), on average. We evaluated baseline predictors of session attendance (%) through multiple regression techniques. No PA, alcohol use, depression/affect score, or demographic variables of interest predicted session attendance (ps>.05) with the exception of the negative affect scale of the PANAS, which was significantly associated with less session attendance (beta=−1.06, p<0.05).

Figure 1.

Session Attendance

3.3 Satisfaction and Acceptability

Only 3 out of the 20 participants reported any prior experience with a Fitbit, and none were using a Fitbit or other type of activity monitor at the time of recruitment. On average, women wore their study Fitbit on approximately 73% of days. Participants reported checking their Fitbit activity tracker display to monitor steps on average 8.4 (SD=6.8) times throughout the day. Participants monitored their PA progress more frequently with the smartphone app (76.9% checked daily, 7.7% several times/week, 15.4% never used the app) than with the Fitbit website (30.8% checked daily, 15.4% several times/week, 15.4% monthly, and 38.5% never used the website). The majority of women (84.6%) used either the Fitbit app or website to monitor their step counts: only 15.4% reported monitoring their step count via the Fitbit band alone.

Satisfaction ratings on the CSQ (out of a possible 4 points) were generally high: quality of program (3.8), would recommend to a friend (3.8), would come back to the program (3.8), overall satisfaction (3.7), program met the participant’s needs (3.7), amount of help received (3.6), helped increase PA (3.5), the kind of program the participant wanted (3.5), and helped recovery from alcohol (3.1).

Reponses on the PEQ with the Fitbit tracker also indicated high satisfaction (out of a possible 5 points). Overall satisfaction with the Fitbit was 4.38. Participants also indicated that using the Fitbit helped them set activity goals (4.38), helped them to be more active (4.23) and helped support their alcohol recovery (3.85). They rated the Fitbit as easy to use and operate (4.62). They reported good understanding of how to use physical activity to manage their mood and cravings (means 4.31). No differences were found on these activity monitor satisfaction measures between those who wore the Fitbit Charge and Fitbit Alta models.

3.4 Alcohol Use, PA, Mental health and Fitness outcomes

Table 1 displays means and standard deviations of each outcome at baseline (n=20) and end of treatment for treatment completers (n=15) and intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses utilizing all patients (n=20). Additionally, Table 1 displays effect sizes for changes in variables of interest over time (Cohen’s dz). Because the same pattern of results emerged for the ITT analyses, we present the results for the treatment completers in the text below.

Table 1.

Intervention Outcomes and Effect Sizes

| Treatment Completers | All Participants (Intent-to-Treat) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Baseline (n=20) | End of Treatment (n=15) | Cohen’s dz | End of Treatment (n=20) | Cohen’s dz | |

| Alcohol Use | |||||

| Alcohol Use (Days) | 51.15(26.13) | 4.20(6.44) | −1.60 | 15.55(23.71) | −1.08 |

| Alcohol Use (% days abstinent) | 0.44(0.29) | 0.95(0.07) | 1.60 | 0.83(0.26) | 1.08 |

| * Drinks per Drinking Day (DDD) | 10.11(6.36) | 5.97(3.63) | −0.40 | 6.72(4.64) | −0.31 |

| Craving | 10.95(7.59) | 6.92(7.94) | −0.47 | 8.25(7.38) | −0.37 |

| Physical Activity (PA) | |||||

| ** Activity (steps) | 5290.47(1477.07) | 9174.61(5518.85) | 0.85 | 8293.40(5195.36) | 0.59 |

| *** All PA (duration) | 75.81(90.64) | 183.83(120.06) | 1.20 | 145.77(124.44) | 0.87 |

| ***MVPA (duration) | 48.49(71.62) | 77.21(57.43) | 0.21 | 66.47(59.10) | 0.18 |

| Exercising to Cope (days) | 2.90(5.98) | 15.67(16.96) | 0.43 | 11.35(15.78) | 0.53 |

| Depression and Anxiety | |||||

| QIDS | 8.74(4.98) | 4.77(3.44) | −0.74 | 6.73(4.86) | −0.53 |

| PHQ-9 | 11.50(3.94) | 3.84(5.11) | −1.12 | 6.45(3.94) | −0.76 |

| GAD-7 | 15.42(6.18) | 8.71(5.57) | −1.11 | 14.15(5.88) | −0.82 |

| Affect | |||||

| PANAS-positive affect | 29.16(8.79) | 36.00(10.24) | 0.52 | 33.42(10.41) | 0.42 |

| PANAS-negative affect | 27.26(7.24) | 18.62(10.24) | −1.12 | 21.53(10.09) | −0.78 |

Note: Values in bold represent statistically significant changes from baseline to end-of-treatment using paired samples t-tests (n=15 for treatment completers, n=20 for baseline-imputed intent-to-treat analyses of all participants).

Drinks per drinking day was only calculated for individuals who consumed alcohol during treatment

Fitbit data allowed for a larger sample size for treatment completer end of treatment step count (n=17).

One participant was excluded from physical activity analyses due to data quality.

Cohen’s dz effect sizes can be interpreted as: small effect0=.2; medium effect=0.5, large effect=0.8

3.4.1 Alcohol Use

Among participants who completed the EOT assessment (n=15), 7 reported complete abstinence over the course of the 12-week intervention (46.7%). Among individuals who consumed alcohol, 4 did so for 3 days or fewer (26.6%). Among treatment completers, participants were abstinent for an average of 95% of days at EOT, which represents a significant increase from baseline (t= 6.21, p<0.01, dz=1.60). Among individuals who relapsed, drinks per drinking day did not significantly decrease (t=−1.19, p=0.27, dz=−0.47).

3.4.2 Physical Activity

Figure 2 is a graphical display of change in steps over the course of treatment for all participants in which data was available. Among all participants at baseline, the average steps/day was 5,290. Among participants who completed the intervention, average steps taken per day significantly increased to 9,174 steps through the course of treatment. This change represents a 73% increase (t=2.81, p=0.01, dz=0.85) in steps/day. Additionally, participants significantly increased their average weekly minutes of all PA (t=4.50, p<.01, dz=1.20), but not MVPA (t=.80, p=.44, dz=0.43).

Figure 2.

Average Steps per Week

3.4.3 Depression, Anxiety, and Affect

Participants reported a significant decrease in depression at EOT, as measured by both the QIDS (t=−2.56, p=0.03, dz= −.74) and PHQ-9 (t=−4.07, p<0.01, dz=−1.12). Negative affect significantly decreased from baseline to EOT, as measured by the PANAS-negative affect scale (t=−4.00, p<0.01, dz=−1.12). Additionally, there was a trend towards significance in reported positive affect as measured by the PANAS (t=1.89, p=0.08, dz=0.52). Scores of generalized anxiety, as measured by the GAD-7), significantly decreased over the course of treatment t=−4.16, p<0.01, dz=−1.11).

3.4.4 Alcohol craving

Among completers, participants’ reporting of alcohol craving from baseline to EOT was not reduced at a statistically significant level (t=−1.70, p=.11, dz=−0.477).

3.4.5 Using Exercise to Cope with negative emotions and alcohol craving

Participants reported a significantly higher frequency of days in the past 90 that they used exercise to cope with negative affect and craving among treatment completers (t=2.49, p=.03, dz=−.43). At the end of treatment assessment, every participant reported that they exercised to cope to some extent.

3.4.6 Cardiorespiratory Fitness and Body Composition

No statistically significant differences were found in cardiovascular fitness and body composition between baseline and end of treatment. Average participant BMI was 28.9 (SD=5.6) at baseline and 29.9(SD=6.7) at EOT. Estimated VO2max was 30.2(SD=6.5) at baseline and 31.8(SD=7.3) at EOT.

3.5 Relationship between PA and Outcomes

Correlational analyses (Table 2) revealed that physical activity, as measured by all activity but not MVPA, was associated with changes in anxiety (r=−0.66, p=0.02) and depression as measured by the PHQ-9 (r=−0.57, p=0.05). Correlational relationships between PA and changes in alcohol use, craving, depression as measured by the QIDS, and affect were not significant. MVPA was not related to any outcome variable.

Table 2.

Correlational Analyses

| All PA r(p) |

MVPA r(p) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Change in Alcohol Use | ||

| Alcohol Use (Days) | −0.40(0.15) | −0.37(0.20) |

| Alcohol Use (% days abstinent) | 0.40(0.15) | 0.37(0.20) |

| Craving | 0.21(0.52) | −0.11(0.73) |

| Change in Depression and Anxiety | ||

| QIDS | −0.30(0.34) | −0.05(0.88) |

| PHQ-9 | −0.57(0.05) | −0.42(0.18) |

| GAD-7 | −0.66(0.02) | −0.26(0.39) |

| Change in Affect | ||

| PANAS-positive affect | 0.31(0.33) | −0.44(0.15) |

| PANAS-negative affect | −0.24(0.45) | 0.08(0.81) |

Note: Values in bold represent statistically significant relationships

One participant was excluded from analyses due to data quality, leaving a sample size of 14.

3.6 Qualitative Interview Results

During interviews at the completion of the trial, participants discussed accountability for engaging in physical activity, support from others, challenging oneself and measuring physical activity progress by step count, and utilizing exercise to cope. See Table 3 for participant quotes.

Table 3.

Qualitative Interview Quotes

Accountability

|

4. Discussion

Building on the existing evidence for the benefits of physical activity in coping with negative affect, we developed a Fitbit-supported lifestyle physical activity intervention for depressed alcohol dependent women. The results of this open pilot trial suggest that the LPA+Fitbit intervention can be feasibly delivered as an adjunctive treatment in the context of early recovery with high satisfaction and acceptability ratings by participants. Preliminary findings also point toward significant increases in physical activity levels over the course of the 12-week intervention.

Though few women had any prior experience with the Fitbit, they reported high levels of engagement and satisfaction with the activity monitor. Indeed, most women self-monitored their step counts multiple times throughout the day to make adjustments in their activity in order to meet daily step count goals. Consistent with Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, 1991), these behavioral practices (i.e., self-monitoring and goal-setting) are key for successfully increasing physical activity (Bird et al., 2013; Olander et al., 2013). In addition, women preferred to monitor physical activity progress with the mobile app rather than through the Fitbit website. This parallels trends identified by market research that mobile devices have overtaken desktops for accessing the internet(Chaffey, 2016). As efforts toward translating addiction treatment into mobile delivery methods are increasing(Cohn, Hunter-Reel, Hagman, & Mitchell, 2011; Gustafson et al., 2014), future iterations of these apps may benefit from integrating physical activity monitoring and support.

Significant increases in overall physical activity were observed during the 12-week intervention. Estimated increases in step counts from baseline to the end of the intervention reflect a 73% increase in steps/day. Prior work has shown that 26% increases in steps/day can results in significant improvements in health outcomes (Bravata et al., 2007). Therefore, this level of increase in physical activity could have an important impact on decreasing the disproportionate health risk evident in women with alcohol use disorders(Schenker, 1997). Interestingly, while increasing total, overall PA time, women did not significantly increase their level of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA). Given that the focus of the intervention was on increasing steps/day through integrating creative ways to be active in their daily lives and utilizing brief bouts of activity in response to negative affect and alcohol cravings, this finding is not entirely surprising and is consistent with a lifestyle physical activity approach. Of note, despite being given instructions to gradually increase activity by 500 steps/day, women immediately increased their steps/day at rates much higher than instructed. Perhaps because lower intensity activities were more feasibly integrated into daily life, higher steps counts/day were noted early in the intervention period. Overall physical activity, but not MVPA, was significantly correlated with reductions in levels of depression and anxiety in our participants, suggesting that physical activity may have been serving in a behavioral activation role for mood improvement (Sturmey, 2009). Indeed, these findings add to the literature that even light levels of physical activity have been associated with significant decreases in mental health symptoms in other populations (Meyer, Koltyn, Stegner, Kim, & Cook, 2016).

Consistent with the goals of the LPA+Fitbit, women did report a significant increase in their use of physical activity to help them cope with negative affect and/or cravings to drink alcohol. While recent intervention efforts have examined the use of brief bouts of physical activity to manage cigarette cravings among individuals undergoing a cessation attempt (Linke, Rutledge, & Myers, 2012), the concept of utilizing bouts of activity “in the moment” to cope with negative affect and/or urges to drink has not been examined in prior exercise studies with alcohol or drug dependent patients. In the qualitative interviews, women also described utilizing physical activity as strategy to prevent negative affect and/or urges when they anticipated high-risk situations. Therefore, as we continue to develop the most effective physical activity interventions for individuals with addictive behaviors, clear guidance on when and how to try bouts of activity to aid mood regulation may lead to better clinical outcomes.

In general, we found good adherence to the phone counseling sessions and the daily use of the Fitbit. Approximately 75% of participants were still engaged in the intervention by the end of the 12 weeks. This rate is consistent to prior exercise intervention studies with alcohol treatment samples (Brown et al., 2014). Yet, there was sharp drop in session attendance and treatment adherence in the first 6–8 weeks of the intervention. This period of early abstinence from alcohol can be a challenging time, suggesting that additional strategies to boost adherence could help to promote sustained engagement in the intervention. Once such strategy could be the delivery of short message service (SMS) text messages that provide additional support for engaging in PA. In other work, SMS text messages have been found to help increase adherence to a physical activity program in a community sample of adults (Voth, Oelke, & Jung, 2016). An additional strategy could involve increasing the amount of social support for PA during this early period. For example, though we did not utilize this feature in the LPA+Fitbit intervention, the Fitbit website and mobile app platforms have social a networking component which allow individuals to “friend” one another, send messages, and compete against each other in step counts. In addition to these digital options for increasing social support, connecting women during outpatient treatment (e.g., through walking groups) may also help facilitate adherence to a physical activity program.

There are a number of limitations that are worth noting. First, the purpose of this study was primarily to demonstrate feasibility and acceptability of the LPA+Fitbit intervention and with the small sample, we must be cautious in interpreting our preliminary PA outcomes. Our sample size did not allow us to detect small effects. Second, the lack of comparison condition prohibits us from making any inference on whether that was due to engaging in physical activity. Third, we lacked a baseline (i.e., before the Fitbit was given to participants) objective measure of PA; rather we used self-reports and estimated step counts. Rather than delay the start of the intervention to obtain a baseline measure following alcohol treatment program discharge, we reasoned that the need for increasing PA was greatest in the early days of sobriety and believed the women could benefit most by starting the LPA+Fitbit intervention immediately. Individuals tend to over report their physical activity levels. Thus, our significant findings represent a conservative estimate of increases in physical activity. Lastly, because the sample was recruited from a partial hospital program, the findings may not generalize to women who receive alcohol treatment in other settings. However, given that the PA counseling is delivered by phone, the LPA+Fitbit intervention has potential to transportable.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the LPA+Fitbit intervention demonstrated promising results and merits future examination in a randomized controlled trial that would more rigorously evaluate the efficacy of the intervention. The results of such a trial would contribute much-needed knowledge on the role of physical activity as alternate coping strategy for managing depressive symptoms and negative mood, and alcohol cravings in women with AUDs, thereby reducing relapse risk. If the efficacy of the LPA+Fitbit intervention can be established, depressed women with AUDs would have a valuable adjunct to traditional alcohol treatment that can be delivered across settings, including standard aftercare.

Highlights.

Depressed alcohol dependent women in early recovery increase physical activity levels with a Fitbit-supported lifestyle physical activity (LPA) intervention.

Increases in activity levels are associated with reductions in anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Women report utilizing bouts of physical activity to help cope with negative affect and alcohol cravings.

A future randomized controlled trial is necessary to test the efficacy of the LPA+Fitbit intervention on alcohol and mental health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant funded by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA; R34 AA024038; PI: Ana M. Abrantes, PhD). NIAAA had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. Thank you to Michelle Turner, Marie Rapoport, and Julie Desaulniers in all their efforts recruiting the study sample.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abrantes AM, Matsko S, Wolfe J, Brown SA. Physical activity and alcohol and drug use disorders. In: Ekkekakis P, editor. Handbook on physical activity and mental health. New York: Routledge; 2013. pp. 465–477. Book Section. [Google Scholar]

- Adam Noah J, Spierer DK, Gu J, Bronner S. Comparison of steps and energy expenditure assessment in adults of Fitbit Tracker and Ultra to the Actical and indirect calorimetry. J Med Eng Technol. 2013;37(7):456–462. doi: 10.3109/03091902.2013.831135. Journal Article. http://doi.org/10.3109/03091902.2013.831135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM … COMBINE Study Research Group. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295(17):2003–2017. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attkisson CC, Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval Program Plann. 1982;5(3):233–237. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Social cognitive theory of self-regulation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50(2):248–287. http://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90022-L. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein EE, McNally RJ. Acute aerobic exercise helps overcome emotion regulation deficits. Cognition & Emotion. 2016:1–10. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2016.1168284. http://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2016.1168284. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bird EL, Baker G, Mutrie N, Ogilvie D, Sahlqvist S, Powell J. Behavior change techniques used to promote walking and cycling: a systematic review. Health Psychology:Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2013;32(8):829–38. doi: 10.1037/a0032078. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0032078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borg G. Perceived exertion as an indicator of somatic stress. Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 1970;2(2):92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady KT, Ashley OS. Women in substance abuse treatment: Results from the Alcohol and Drug Services Study (ADSS) (DHHS Publication No. SMA 04-3968, Analytic Series A-26) Book, Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Vidrine JI, Litvin EB. Relapse and Relapse Prevention. The Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:257–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091455. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravata DM, Smith-Spangler C, Sundaram V, Gienger AL, Lin N, Lewis R, … Sirard JR. Using pedometers to increase physical activity and improve health: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;298(19):2296–304. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.19.2296. http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.19.2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brienza RS, Stein MD. Alcohol use disorders in primary care: do gender-specific differences exist? J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):387–397. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10617.x. Journal Article. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Abrantes AM, Minami H, Read JP, Marcus BH, Jakicic JM, … Stuart GL. A preliminary, randomized trial of aerobic exercise for alcohol dependence. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2014;47(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Abrantes AM, Read JP, Marcus BH, Jakicic J, Strong DR, … Gordon AA. Aerobic exercise for alcohol Recovery: rationale, program description, and preliminary findings. Behavior Modification. 2009;33:220–249. doi: 10.1177/0145445508329112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Prince MA, Minami H, Abrantes AM. An exploratory analysis of changes in mood, anxiety and craving from pre- to post-single sessions of exercise, over 12 weeks, among patients with alcohol dependence. Mental Health and Physical Activity. 2016;11:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker P, Otto R, Whaley M. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. American College of Sports Medicine; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cairney J, Kwan M, Veldhuizen S, Faulkner GE. Who Uses Exercise as a Coping Strategy for Stress? Results From a National Survey of Canadians. J Phys Act Health. 2013 doi: 10.1123/jpah.2012-0107. Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffey D. Statistics on consumer mobile usage and adoption to inform your mobile marketing strategy mobile site design and app development 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Cohn AM, Hunter-Reel D, Hagman BT, Mitchell J. Promoting Behavior Change from Alcohol Use Through Mobile Technology: The Future of Ecological Momentary Assessment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2011;35(12):2209–2215. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01571.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01571.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Jarrett PJ, Thase ME, Fabrega H, Jr, Haas GL, Jones-Barlock A, … Ulrich RF. Gender effects on the clinical presentation of alcoholics at a psychiatric hospital. Compr Psychiatry. 1995;36(6):435–440. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(95)90251-1. Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croteau KA. Strategies used to increase lifestyle physical activity in a pedometer-based intervention. Journal of Allied Health. 2004;33(4):278–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn AL, Marcus BH, Kampert JB, Garcia ME, Kohl HW, 3rd, Blair SN. Comparison of lifestyle and structured interventions to increase physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness: a randomized trial. JAMA. 1999;281(4):327–334. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.4.327. Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekkekakis P, Hall EE, VanLanduyt LM, Petruzzello SJ. Walking in (affective) circles: Can short walks enhance affect? Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2000;23(3):245–275. doi: 10.1023/a:1005558025163. http://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005558025163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensari I, Greenlee TA, Motl RW, Petruzzello SJ. Meta-Analysis of Acute Exercise Effects on State Anxiety: an Update of Randomized Controlled Trials Over the Past 25 Years. Depression and Anxiety. 2015;32(8):624–634. doi: 10.1002/da.22370. http://doi.org/10.1002/da.22370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB. The Encyclopedia of Clinical Psychology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2014. Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID) http://doi.org/10.1002/9781118625392.wbecp351. [Google Scholar]

- Flannery BA, Volpicelli JR, Pettinati HM. Psychometric Properties of the Penn Alcohol Craving Scale. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1999;23(8):1289–1295. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.1999.tb04349.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulk GD, Combs SA, Danks KA, Nirider CD, Raja B, Reisman DS. Accuracy of 2 activity monitors in detecting steps in people with stroke and traumatic brain injury. Phys Ther. 2014;94(2):222–229. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20120525. Journal Article. http://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20120525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Chih MY, Atwood AK, Johnson RA, Boyle MG, … Shah D. A smartphone application to support recovery from alcoholism: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4642. http://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hartka E, Johnstone B, Leino EV, Motoyoshi M, Temple MT, Fillmore KM. A meta-analysis of depressive symptomatology and alcohol consumption over time. Br J Addict. 1991;86(10):1283–1298. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01704.x. Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heesch KC, Dinger MK, McClary KR, Rice KR. Experiences of women in a minimal contact pedometer-based intervention: a qualitative study. Women Health. 2005;41(2):97–116. doi: 10.1300/J013v41n02_07. Journal Article. http://doi.org/10.1300/J013v41n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendershot CS, Witkiewitz K, George WH, Marlatt GA. Relapse prevention for addictive behaviors. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy. 2011;6(1747–597X, 1747–597X):17. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-6-17. http://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54(4):313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. 2001;46202:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvam S, Kleppe CL, Nordhus IH, Hovland A. Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2016;15(202):67–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.03.063. Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology. 2013;4(V):1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863. http://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauzon N, Chan CB, Myers AM, Tudor-Locke CE. Participant experiences in a workplace pedometer-based physical activity program. Journal of Physical Activity & Health. 2008;5(5):675–687. doi: 10.1123/jpah.5.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JM, Kim Y, Welk GJ. Validity of Consumer-Based Physical Activity Monitors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2014 doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000287. Journal Article. http://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000287. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lehavot K, Stappenbeck CA, Luterek JA, Kaysen D, Simpson TL. Gender differences in relationships among PTSD severity, drinking motives, and alcohol use in a comorbid alcohol dependence and PTSD sample. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28(1):42–52. doi: 10.1037/a0032266. Journal Article. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0032266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC. The Role and Interpretation of Pilot Studies in Clinical Research. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2011;45(5):626–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.008. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linke SE, Rutledge T, Myers MG. Intermittent exercise in response to cigarette cravings in the context of an Internet-based smoking cessation program. Mental Health and Physical Activity. 2012;5(1):85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.mhpa.2012.02.001. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Donovan DM. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors, Second Edition. Book, New York: Guildford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer K, Giangregorio L, Schneider E, Chilana P, Li M, Grindrod K. Acceptance of Commercially Available Wearable Activity Trackers Among Adults Aged over 50 and With Chronic Illness: A Mixed-Methods Evaluation. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2016;4(1):e7. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merom D, Rissel C, Phongsavan P, Smith BJ, Van Kemenade C, Brown WJ, Bauman AE. Promoting Walking with Pedometers in the Community. The Step-by-Step Trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2007;32(4):290–297. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.007. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer JD, Koltyn KF, Stegner AJ, Kim JS, Cook DB. Influence of Exercise Intensity for Improving Depressed Mood in Depression: A Dose-Response Study. Behavior Therapy. 2016;47(4):527–537. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2016.04.003. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- mobihealthnews. Fitibit shipped the most activity trackers in 2013. 2014. [Web Page] [Google Scholar]

- Mokdad AH, Marks JS, Stroup DF, Gerberding JL. Actual causes of death in the United States, 2000. JAMA. 2004;291(10):1238–1245. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.10.1238. Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MH, Nevill AM, Murtagh EM, Holder RL. The effect of walking on fitness, fatness and resting blood pressure: A meta-analysis of randomised, controlled trials. Preventive Medicine. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.12.008. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Murphy TJ, Pagano RR, Marlatt GA. Lifestyle modification with heavy alcohol drinkers: effects of aerobic exercise and meditation. Addictive Behaviors. 1986;11(2):175–186. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(86)90043-2. Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers WR. Handling Missing Data in Clinical Trials: An Overview. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science. 2000;34(2):525–533. http://doi.org/10.1177/009286150003400221. [Google Scholar]

- Nigg CR, Borrelli B, Maddock J, Dishman RK. A Theory of Physical Activity Maintenance. Applied Psychology. 2008;57(4):544–560. Journal Article. [Google Scholar]

- Olander EK, Fletcher H, Williams S, Atkinson L, Turner A, French DP. What are the most effective techniques in changing obese individuals’ physical activity self-efficacy and behaviour: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2013;10(29):29. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-10-29. http://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panza GA, Weinstock J, Ash GI, Pescatello LS. Psychometric Evaluation of the Timeline Followback for Exercise among College Students. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2012;13(6):779–788. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.06.002. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Project Match Research Group. Matching Alcoholism Treatments to Client Heterogeneity: Project MATCH posttreatment drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58(1):7–29. http://doi.org/10.15288/jsa.1997.58.7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed J, Buck S. The effect of regular aerobic exercise on positive-activated affect: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2009 http://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.05.009.

- Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. The Lancet. 2009 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. http://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ritchie C. Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) Journal of Physiotherapy. 2012;58:62. doi: 10.1016/S1836-9553(12)70078-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson R, Robertson A, Jepson R, Maxwell M. Walking for depression or depressive symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mental Health and Physical Activity. 2012;5(1):66–75. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2012.03.002. [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, … Keller MB. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): a psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon J, Owen N, Crawford D, Bauman A, Sallis JF. Physical activity and sedentary behavior: a population-based study of barriers, enjoyment, and preference. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2003;22(2):178–88. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.22.2.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez K, Walker R, Campbell AN, Greer TL, Hu MC, Grannemann BD, … Trivedi MH. Depressive Symptoms and Associated Clinical Characteristics in Outpatients Seeking Community-based Treatment for Alcohol and Drug Problems. Subst Abus. 2014 doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.937845. Journal Article. http://doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2014.937845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Schenker S. Medical consequences of alcohol abuse: is gender a factor? Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21(1):179–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1997.tb03746.x. Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinyor D, Brown T, Rostant L, Seraganian P. The role of a physical fitness program in the treatment of alcoholism. J Stud Alcohol. 1982;43(3):380–386. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1982.43.380. Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline followback: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, Litten R, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biological Methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Lo B. A Brief Measure for Assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder. 2017;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturmey P. Behavioral activation is an evidence-based treatment for depression. Behavior Modification. 2009;33(6):818–829. doi: 10.1177/0145445509350094. http://doi.org/10.1177/0145445509350094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudor-Locke C, Bassett DR., Jr How many steps/day are enough? Preliminary pedometer indices for public health. Sports Med. 2004;34(1):1–8. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200434010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudor-locke C, Craig CL, Brown WJ, Clemes SA, Cocker K, De Giles-corti B, … Blair SN. How Many Steps/day are Enough ? For Adults. 2011:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tudor-Locke C, Lutes L. Why do pedometers work?: A reflection upon the factors related to successfully increasing physical activity. Sports Medicine. 2009 doi: 10.2165/11319600-000000000-00000. http://doi.org/10.2165/11319600-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tudor-Locke C, Pangrazi RP, Corbin CB, Rutherford WJ, Vincent SD, Raustorp A, … Cuddihy TF. BMI-referenced standards for recommended pedometer-determined steps/day in children. Prev Med. 2004;38(6):857–864. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.018. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ussher M, Sampuran AK, Doshi R, West R, Drummond DC. Acute effect of a brief bout of exercise on alcohol urges. Addiction. 2004;99(12):1542–1547. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00919.x. Journal Article. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voth EC, Oelke ND, Jung ME. A Theory-Based Exercise App to Enhance Exercise Adherence: A Pilot Study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth. 2016;4(2):e62. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.4997. http://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.4997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walitzer KS, Dearing RL. Gender differences in alcohol and substance use relapse. Clin Psychol Rev. 2006;26(2):128–148. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.11.003. Journal Article. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. Journal Article. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner M, Helmich I, Machado S, Nardi EA, Arias-Carrion O, Budde H. Effects of Exercise on Anxiety and Depression Disorders: Review of Meta- Analyses and Neurobiological Mechanisms. CNS & Neurological Disorders - Drug Targets. 2014;13(6):1002–1014. doi: 10.2174/1871527313666140612102841. http://doi.org/10.2174/1871527313666140612102841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, McHugo GJ, Fox MB, Drake RE. Substance abuse relapse in a ten-year prospective follow-up of clients with mental and substance use disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56(10):1282–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.10.1282. http://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.10.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]