Abstract

Purpose

To examine the associations of nerve fiber layer (NFL) thickness with other ocular characteristics in older adults.

Methods

Participants in the Beaver Dam Eye Study (2008–2010) underwent spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) scans of the optic nerve head, imaging of optic discs, frequency doubling technology (FDT) perimetry, measurement of intraocular pressure (IOP), and an interview concerning their history of glaucoma and use of drops to lower eye pressure. Self-reported histories of glaucoma and the use of drops to lower eye pressure were obtained at follow-up examinations (2014–2016).

Results

NFL thickness measured on OCT’s varied by location around the optic nerve. Age was associated with mean NFL thickness. Mean NFL was thinnest in eyes with larger cup/disc (C/D) ratios. Horizontal hemifield defects or other optic nerve- field defects were associated with thinner NFL. NFL in persons who reported taking eye drops for high intraocular pressure was thinner compared to those not taking drops. After accounting for the presence of high intraocular pressure, large C/D ratios or hemifield defects, eyes with thinner NFL in the arcades were more likely (OR=2.3 for 30 micron thinner NFL, p=0.04) to have incident glaucoma at examination 5 years later.

Conclusion

Retinal NFL thickness was associated with a new history of self-reported glaucoma 5 years later. A trial testing the usefulness of NFL as part of a screening battery for predicting glaucoma in those previously undiagnosed might lead to improved case finding and, ultimately, to diminishing the risk of visual field loss.

Keywords: nerve fiber layer, glaucoma, visual field, SD-OCT, FDT

INTRODUCTION

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the posterior pole of the eye is now a widely available imaging technique that provides information to assess characteristics of the retina such as thickness of retinal layers as well as other ocular structures in normal eyes and in those with a variety of ocular conditions and traits. Such testing can be performed in a short period of time with minimal discomfort to the individual. Thickness of the nerve fiber layer (NFL) has been reported to be thinner in persons with even moderately high or sporadically elevated intraocular pressures and in persons suspected of having glaucoma.1–5 Further, specific anatomic distributions of NFL thinning may be found in persons with glaucoma.

Other traits that are concomitants or harbingers of open angle glaucoma are larger optic cup-to-disc ratios (C/D) and particular patterns of visual field deficits. At higher levels, these characteristics are used as diagnostic criteria for open angle glaucoma. At lower levels, where glaucoma has not been diagnosed, they may be predictors or biomarkers of incipient disease. It is the purpose of our report to examine whether NFL thickness, as measured by SD-OCT, is associated with not only visual field loss as measured by frequency doubling technology (FDT) perimetry, but with other ocular characteristics typical of glaucoma found in a group of older adults participating in the Beaver Dam Eye Study who were not selected for participation based on the presence or suspicion of glaucoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Population

There were 5,924 eligible persons identified in a private census of the town of Beaver Dam, Wisconsin, of whom 4,926 participated in the baseline examination of the Beaver Dam Eye Study between March 1, 1988, and September 15, 1990.6;7 Subjects were invited to 4 follow-up examinations spaced 5 years apart. The analyses and findings reported here are limited to the 2,513 eyes from 1,410 individuals who participated in the 20-year follow-up in 2008–2010, the first examination at which SD-OCT scans were obtained. An additional follow-up occurred in 2014–2016, during which a history of glaucoma and use of drops to lower eye pressure was ascertained. Comparisons between participants and nonparticipants at each examination have appeared elsewhere.7–11 Ninety-nine percent of the population was white. Approval for this study was granted by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Informed consent was obtained from each participant before every examination. The study operations were performed in adherence to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. The tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki were observed.

Procedures and Grading

Standardized interviews and examinations were performed at each visit and included information on demographic characteristics, including history of glaucoma and current use of eye drops for high pressure in the eye. Measurements were taken of weight, height, refraction, blood pressure and visual acuity. Intraocular pressure was measured by applanation tonometry using a Goldmann tonometer after topical anesthesia.

Visual field perimetry was tested with the Humphrey Matrix Visual Field Instrument N-30-F program. The perimetry was graded manually by a grader who was masked to subject characteristics (CAJ). Specific patterns were categorized according to a modification of the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study classification, and any of the following was considered positive for a defect in a horizontal hemifield: altitudinal, arcuate, nasal step, partial arcuate or double arcuate defect.12 Central or widespread defects were also noted.

Stereoscopic 30° color fundus photographs centered on the disc (field 1) and macula (field 2) were obtained for each eye using the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study protocol.13 Optic disc and cup measurements were obtained from images of photographic field 1 (stereoscopic images centered on the optic disc).14

Spectral domain optical coherence tomography images were obtained using the Topcon 3D-OCT 1000-Mark II (Topcon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The scans were processed with the Iowa Reference Algorithms,15;16 which centers a grid using anatomical features and identifies 11 layers where changes in intensity are detectable. The NFL was measured as the thickness from the top two surfaces (inner limiting membrane [ILM] to NFL surface) in 12 equal segments (corresponding to clock hours) within a donut-shaped ring between 1.4 and 2.0 mm radii from the center of the optic disc.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses of nerve fiber layer thickness were performed using a multilevel modelling approach which allowed for each grid region to be nested within each eye and further nested within a single participant, so relationships between each covariate and retinal thickness measure could be assessed at an eye specific level while accounting for the correlations between the two eyes from a single participant. Inclusion of a level for the grid region allows for assessment of similarity/differences of associations between NFL and the ocular characteristics across the grid regions. All models were adjusted for age and sex. Refractive error was not adjusted for because a large portion of the population does not have this measure due to cataract surgery. Since there are very low rates of high myopia in the population, we do not expect refraction differences to affected associations. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for all analyses.

Intraocular pressures were divided into categories for analysis (less than 12, 12–18, 19–21, and 22 mmHg or greater). The eyes of persons taking drops to control intraocular pressure (IOP) were analyzed as a separate group. The C/D ratio was categorized as small (less than 0.2), normal (0.2 or greater, but less than 0.6), moderately large (0.6 or greater, or less than 0.6 with asymmetry greater than 0.2 between eyes) and very large (0.8 or greater, or 0.6 or greater with asymmetry between eyes).

Glaucoma prevalence reflects a positive response to a question that is part of the study evaluation. Incidence of glaucoma was defined as a positive response to the same question at the follow-up examination (five years later) among those who did not report glaucoma at the analysis visit.

To allow the NFL thickness for each region (arcades, nasal, temporal) to be displayed on the same scale (for graphical purposes), the thickness values were centered by subtracting the population mean thickness within each region.

RESULTS

Among the 1,913 persons examined at the 20-year follow-up of the Beaver Dam Eye Study, 216 were seen off-site and 162 were unable to have an SD-OCT scan performed (due to inability to position or time constraints). SD-OCT scans were obtained on a total of 1,535 participants (3,070 eyes). Of these 3,070 eyes, 21 were excluded due to surgery for glaucoma, 44 did not have an optic nerve head scan available, 191 had incomplete data (z-offset or other grid segment data missing), and 301 had a Q-score of less than 70 and were excluded. These analyses are on the 2,513 eyes with complete optic nerve head data (1,103 people with scans in both eyes, 125 right eye only, 182 left eye only).

There were systematic differences in thickness of the NFL in the 12 segments according to location in both eyes (Table 1 and Figure 1). In the right eye, the thickest regions were at the arcades at 11:00 and 12:00 and 6:00 and 7:00. Similarly, in the left eye the thickest regions were at 5:00 and 6:00 and 12:00 and 1:00 positions. The clock hour regions were combined for remaining analyses. Thickness in the arcade regions were about 125 microns, nasal regions about 86 microns, and temporal regions about 70 microns thick. The mean NFL thickness of the regions decreased with increasing age category (Figure 2 and Table 2), except for the temporal region (p-value varied from 0.001 for arcades to 0.09 for the temporal region). The decrease was not linear, however, with the largest changes happening in the 75–79-year-old group. The NFL was slightly thicker in men than in women after adjusting for age, especially in the temporal region (p=0.09 in arcades and p <0.001 in temporal) (Table 2).

Table 1.

Mean Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness (µm) by Clock Hour Location in Each Eye.

| Right Eye (N = 1,228) | Left Eye (N = 1,285) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Location | Region | Mean | SD | Region | Mean | SD |

| 12:00 | Arcades | 111.8 | 26.2 | Arcades | 118.0 | 26.6 |

| 1:00 | Nasal | 100.6 | 20.8 | Arcades | 125.2 | 24.9 |

| 2:00 | Nasal | 92.7 | 21.0 | Temporal | 81.7 | 16.8 |

| 3:00 | Nasal | 63.1 | 14.3 | Temporal | 55.2 | 11.0 |

| 4:00 | Nasal | 76.7 | 18.1 | Temporal | 70.0 | 17.2 |

| 5:00 | Nasal | 100.5 | 24.1 | Arcades | 130.1 | 25.0 |

| 6:00 | Arcades | 129.9 | 27.6 | Arcades | 126.7 | 27.5 |

| 7:00 | Arcades | 128.6 | 26.0 | Nasal | 98.3 | 23.2 |

| 8:00 | Temporal | 69.7 | 16.5 | Nasal | 72.3 | 16.3 |

| 9:00 | Temporal | 56.6 | 10.9 | Nasal | 61.2 | 13.4 |

| 10:00 | Temporal | 86.4 | 17.8 | Nasal | 91.4 | 21.5 |

| 11:00 | Arcades | 132.0 | 23.6 | Nasal | 109.6 | 22.8 |

SD, standard deviation

Figure 1.

Mean retinal nerve fiber layer thickness (µm) by region (nasal, temporal, arcades).

Figure 2.

Association of age with nerve fiber layer thickness by region, centered by subtracting population mean (arcades=125, nasal=85, temporal=70) for each region.

Table 2.

Factors Associated with Nerve Fiber Layer Thickness in the Beaver Dam Eye Study

| Eyes (N) | Mean NFL Thickness (Model estimated) |

Beta Estimates | P value for Similar Beta Estimate Across Regions |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Arcades | Nasal | Temporal | |||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||

| Factor | Right | Left | Arcades | Nasal | Temporal | Comparison | Beta | P value |

Beta | P value |

Beta | P value |

Nasal vs Arcades |

Temporal vs Nasal |

Any Regions |

| Age (years) | |||||||||||||||

| <70 | 431 | 441 | 127.85 | 86.91 | 70.76 | ||||||||||

| 70–74 | 324 | 342 | 127.66 | 87.84 | 70.48 | vs. <70 | −0.19 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.34 | −0.28 | 0.74 | 0.26 | 0.36 | 0.49 |

| 75–79 | 223 | 244 | 124.16 | 86.79 | 68.40 | vs. 70–74 | −3.50 | 0.008 | −1.05 | 0.35 | −2.08 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.50 | 0.10 |

| 80–84 | 157 | 161 | 119.37 | 84.29 | 69.30 | vs. 75–79 | −4.79 | 0.002 | −2.49 | 0.07 | 0.90 | 0.43 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.002 |

| ≥85 | 93 | 97 | 116.80 | 82.44 | 70.42 | vs. 80–84 | −2.57 | 0.19 | −1.86 | 0.27 | 1.12 | 0.43 | 0.68 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| Overall | <.001 | 0.002 | 0.09 | ||||||||||||

| Test for trend | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.14 | ||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Sex | |||||||||||||||

| Female | 686 | 720 | 125.53 | 86.53 | 71.26 | ||||||||||

| Male | 542 | 565 | 124.62 | 86.32 | 68.46 | vs. Female | −1.49 | 0.09 | −0.44 | 0.57 | −2.83 | <.001 | 0.18 | 0.02 | 0.06 |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Intraocular Pressure (mmHg) | |||||||||||||||

| No Glaucoma Drops Used | |||||||||||||||

| < 12 | 61 | 66 | 128.22 | 89.10 | 71.77 | vs 12–18 | 2.38 | 0.10 | 2.18 | 0.09 | 1.65 | 0.14 | 0.88 | 0.76 | 0.89 |

| 12–18 | 945 | 972 | 126.40 | 87.09 | 70.39 | ||||||||||

| 19–21 | 115 | 146 | 124.33 | 86.10 | 68.93 | vs 12–18 | −2.14 | 0.03 | −1.00 | 0.26 | −1.56 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.65 | 0.45 |

| 22+ | 40 | 32 | 123.43 | 83.94 | 69.77 | vs 12–18 | −3.33 | 0.09 | −3.33 | 0.06 | −0.71 | 0.64 | 1.00 | 0.28 | 0.43 |

| Overall | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.08 | ||||||||||||

| Test for trend | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.05 | ||||||||||||

| Glaucoma Drops Used | |||||||||||||||

| No | 1163 | 1219 | 126.19 | 86.99 | 70.29 | ||||||||||

| Yes | 65 | 66 | 106.11 | 76.55 | 65.28 | vs no | −18.61 | <.001 | −9.92 | <.001 | −5.09 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.03 | <.001 |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Cup/disc ratio | |||||||||||||||

| Small | 80 | 83 | 126.04 | 84.44 | 71.23 | vs. Normal | 0.20 | 0.86 | −2.58 | 0.008 | 0.78 | 0.34 | 0.006 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Normal | 1014 | 1043 | 126.07 | 87.12 | 70.34 | ||||||||||

| Moderately large | 102 | 138 | 118.42 | 83.00 | 67.08 | vs. Normal | −7.49 | <.001 | −4.04 | <.001 | −3.27 | <.001 | <.001 | 0.54 | <.001 |

| Very Large | 11 | 2 | 110.05 | 76.90 | 63.60 | vs. Normal | −15.48 | <.001 | −9.92 | 0.002 | −6.91 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.48 | 0.04 |

| Overall | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||||||||||

| Test for trend | <.001 | 0.08 | <.001 | ||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Visual field evaluation | |||||||||||||||

| Normal | 696 | 728 | 127.15 | 87.39 | 70.25 | ||||||||||

| Central defect | 44 | 47 | 118.16 | 84.18 | 70.12 | vs. Normal | −8.28 | <.001 | −3.10 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.87 | <.001 | 0.06 | <.001 |

| Widespread defect(s) | 29 | 41 | 121.99 | 83.96 | 71.82 | vs. Normal | −4.88 | 0.004 | −3.41 | 0.03 | 1.65 | 0.20 | 0.34 | 0.02 | 0.002 |

| Horizontal hemifield defect | 66 | 53 | 112.33 | 81.07 | 69.87 | vs. Normal | −13.81 | <.001 | −6.12 | <.001 | −0.13 | 0.90 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 |

| Overall | <.001 | <.001 | 0.63 | ||||||||||||

| Test for trend | <.001 | 0.15 | 0.51 | ||||||||||||

NFL, nerve fiber layer

In persons not using drops to lower IOP, the NFL was thinner in the region of the vascular arcades in persons with higher IOP with significantly thinner values the higher the category of IOP (p=0.02 (Figure 3 and Table 2)). The decrease seen with increasing IOP is roughly linear for the categories of IOP, which is not evenly distributed across the IOP range. For those taking such medications, the NFL was markedly thinner compared to those who were not (p<0.001) (Figure 3 and Table 2).

Figure 3.

Association of intraocular pressure (mmHg) and the use of drops for glaucoma with nerve fiber layer thickness by region, centered by subtracting population mean (arcades=125, nasal=85, temporal=70) for each region.

There was a systematic decrease in NFL thickness as C/D ratio increased (Figure 4 and Table 2). Those with very large C/D ratio (0.8 or higher) had the thinnest NFL (110 microns in arcades), but even those with moderately large C/D (0.6 or higher or <0.6 with an asymmetry of 0.2 or higher between the eyes) had significantly thinner NFL in each of the grid regions (118 vs 126 microns in the arcades, 83 vs 87 microns in the nasal and 67 vs 70 microns in the temporal regions, p<.001 for each).

Figure 4.

Association of cup/disc ratio with nerve fiber layer thickness by region, centered by subtracting population mean (arcades=125, nasal=85, temporal=70) for each region.

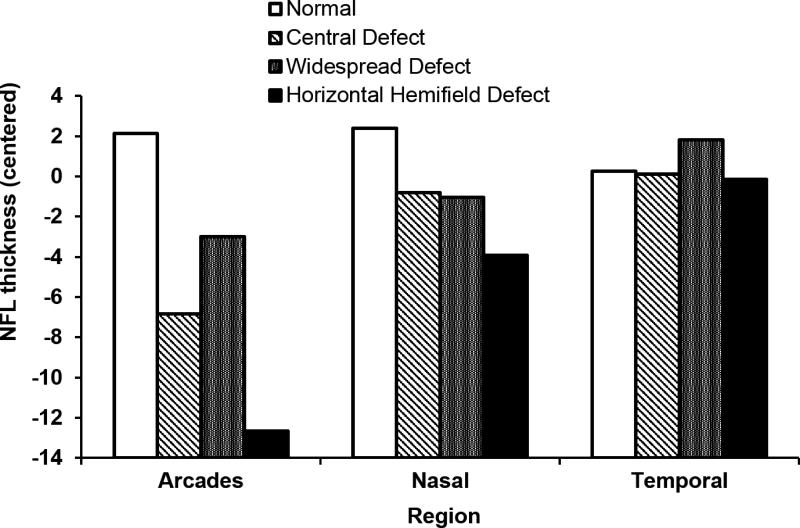

NFL was thinner in the arcades and nasal region for those with hemifield defects FDT perimetry as defined in Procedures (see Figure 5) as compared to eyes with no notable defects (112 vs 127 microns in the arcades). In addition, the NFL was thinner in eyes with a central or widespread defect, even after adjustment for age.

Figure 5.

Association of visual field defects as measured by frequency doubling technology perimetry with nerve fiber layer thickness by region, centered by subtracting population mean (arcades=125, nasal=85, temporal=70) for each region.

All of these ocular characteristics may also be present in persons with glaucoma, so we evaluated the association of each of these characteristics to self-reported glaucoma (Supplementary Figure 1). Use of drops to lower IOP and presence of the largest cup/disc category (>0.8 in an eye or >0.6 with asymmetry of at least 0.2 between the eyes) showed the highest rate of self-reported glaucoma (>50%). Glaucoma was more commonly reported in those with thinner NFL in all segments, as well as those with larger C/Ds, higher IOPs and hemifield defects than in those without these characteristics.

To evaluate whether the NFL could provide additional information on the risk of glaucoma after five years, we evaluated self-reported incidence approximately five years after the 2008–2010 examination. Because there were only 53 of 2194 eyes of persons with incident glaucoma, we were unable to evaluate each characteristic separately. Instead, we defined eyes as high-risk based on the presence of larger C/D (>0.6 or with asymmetry >0.2), higher IOP (22+ and not taking drops), or hemifield defect identified at the examination. Most participants taking drops for glaucoma/intraocular pressure and those with very large C/D ratio were already prevalent cases of glaucoma and were not included for incidence analyses. In models accounting for high- (or low-) risk, eyes with thinner NFL in the arcade region were more likely to have incident glaucoma at the five-year follow-up examination (OR=2.3 per 30-micron decrease in NFL thickness, 95% CI (1.0, 4.9), p=0.04). Similar trends existed for NFL in the nasal and temporal regions, but did not reach statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

In an older population of adults of European ancestry, the retinal NFL was thinner in those with various characteristics consistent with glaucoma. Further, those with thinner NFL, despite presence of other characteristics, were more likely to report incident glaucoma at follow-up about 5 years later.

In our cross-sectional data, the NFL was thinner in individuals with larger C/D ratios. This may reflect the association with visual functional loss (FDT pattern) that reflects the presence of glaucoma, whether or not it has been reported. While this finding is not surprising, what is remarkable is that this relationship is detectable in a putatively normal older population that has, in general, been under standard care. Nearly all persons reported seeing an optometrist or ophthalmologist for care (not part of the study team) on a regular basis, as is true of the majority of older U.S. adults. It has been proposed that SD-OCT measurements be incorporated in machine-based screening for glaucomatous progression.17 Our incidence data corroborates the notion that OCT changes may presage incident glaucoma. A meta-analysis of screening for glaucoma that incorporates SD-OCT suggests that such an approach is feasible.18 A test of this method in a field setting may prove it to be a useful addition to public health efforts to decrease incidence and subsequent vision loss associated with glaucoma.

Our incidence data supports the importance of IOP even at a relatively moderate level as a predictor of self-reported glaucoma in those not taking drops, suggesting that relatively modest elevations are not perceived as increasing the risk of glaucoma in this well-cared-for group of seniors. Thinning of NFL on OCT seems to add significant information as a risk predictor.

Limitations of our study include the relatively small size of our community subjects and the lack of long-term data on visual fields and OCT. In addition, our study group is white and we do not know whether racial/ethnic differences would have affected the relationships found. Also, the study participants are the survivors of a population defined nearly 30 years prior to this report. While it seems unlikely that selective survival and selective participation have materially influenced our findings, we cannot be sure that this is the case. Finally, we identified those with glaucoma based on self-report, which may be in error and may lead to an under- or over-estimate of the importance of any specific risk characteristic.

In summary, in an older population of European-derived adults, retinal NFL thickness decreases with age as well as with increasing C/D ratio and in the presence of visual hemifield defects of FDT that are characteristic of glaucoma in cross-sectional data. Thinner NFL, especially in the arcades, is associated with a five-year incidence of self-reported glaucoma. A follow-up of this study with a trial of glaucoma screening incorporating OCT would be informative as to whether NFL thickness is useful in predicting the development of overt visual function deficits that may impact mobility and other activities of daily life, which are especially problematic in older adults.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Percentage of glaucoma occurrence as measured by cup/disc ratio, frequency doubling technology, intraocular pressure, and use of drops for glaucoma.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This study was supported by grants EY06594 (BEK Klein, R Klein), EB004640 (Sonka), EY018853 (Sonka, Abràmoff), and EY019112 (Sonka, Abràmoff) from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD; an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY; the Stephen A. Wynn Institute for Vision Research, Iowa City, IA; the Department of Veterans' Affairs Merit Program, Washington, DC; and the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Initiative for Macular Research, Irvine, CA.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Eye Institute, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Sonka and Dr. Abràmoff report patents and personal financial interest in IDx LLC (Iowa City, IA, USA). All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

Submission Statement: This submission has not been published anywhere previously and it is not simultaneously being considered for any other publication. An abstract of this study was presented at the 2015 Annual Meeting of the Association for Research and Vision in Ophthalmology (ARVO), Denver, Colorado, USA, May 3–7, 2015.

References

- 1.Prokosch V, Eter N. Correlation between early retinal nerve fiber layer loss and visual field loss determined by three different perimetric strategies: white-on-white, frequency-doubling, or flicker-defined form perimetry. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252(10):1599–1606. doi: 10.1007/s00417-014-2718-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horn FK, Mardin CY, Bendschneider D, et al. Frequency doubling technique perimetry and spectral domain optical coherence tomography in patients with early glaucoma. Eye (London) 2011;25(1):17–29. doi: 10.1038/eye.2010.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu S, Yu M, Weinreb RN, et al. Frequency-doubling technology perimetry for detection of the development of visual field defects in glaucoma suspect eyes: a prospective study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132(1):77–83. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.5511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim TW, Zangwill LM, Bowd C, et al. Retinal nerve fiber layer damage as assessed by optical coherence tomography in eyes with a visual field defect detected by frequency doubling technology perimetry but not by standard automated perimetry. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(6):1053–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Springelkamp H, Lee K, Wolfs RC, et al. Population-based evaluation of retinal nerve fiber layer, retinal ganglion cell layer, and inner plexiform layer as a diagnostic tool for glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(12):8428–8438. doi: 10.1167/iovs.14-15506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linton KL, Klein BE, Klein R. The validity of self-reported and surrogate-reported cataract and age-related macular degeneration in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134(12):1438–1446. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein R, Klein BE, Linton KL, De Mets DL. The Beaver Dam Eye Study: visual acuity. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(8):1310–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(91)32137-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein R, Klein BE, Lee KE. Changes in visual acuity in a population. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(8):1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30526-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein R, Klein BE, Lee KE, et al. Changes in visual acuity in a population over a 10-year period: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(10):1757–1766. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00769-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein R, Klein BE, Lee KE, et al. Changes in visual acuity in a population over a 15-year period: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(4):539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein R, Lee KE, Gangnon RE, Klein BE. Incidence of visual impairment over a 20-year period: the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(6):1210–1219. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keltner JL, Johnson CA, Cello KE, et al. Classification of visual field abnormalities in the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(5):643–650. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.5.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grading diabetic retinopathy from stereoscopic color fundus photographs--an extension of the modified Airlie House classification. ETDRS report number 10. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(5 Suppl):786–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein BE, Magli YL, Richie KA, et al. Quantitation of optic disc cupping. Ophthalmology. 1985;92(12):1654–1656. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(85)34085-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abràmoff MD, Garvin MK, Sonka M. Retinal imaging and image analysis. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2010;3:169–208. doi: 10.1109/RBME.2010.2084567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garvin MK, Abràmoff MD, Wu X, et al. Automated 3-D intraretinal layer segmentation of macular spectral-domain optical coherence tomography images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2009;28(9):1436–1447. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2009.2016958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Belghith A, Bowd C, Medeiros FA, et al. Learning from healthy and stable eyes: A new approach for detection of glaucomatous progression. Artif Intell Med. 2015;64(2):105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.artmed.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas SM, Jeyaraman M, Hodge WG, et al. The effectiveness of teleglaucoma versus in-patient examination for glaucoma screening: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e113779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113779. Correction in: PLoS One. 2015 Mar 5;10(3):e0118688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Percentage of glaucoma occurrence as measured by cup/disc ratio, frequency doubling technology, intraocular pressure, and use of drops for glaucoma.