Abstract

Group-randomized trials (GRTs) are randomized studies that allocate intact groups of individuals to different comparison arms. A frequent practical limitation to adopting such research designs is that only a limited number of groups may be available, and therefore, simple randomization is unable to adequately balance multiple group-level covariates between arms. Therefore, covariate-based constrained randomization was proposed as an allocation technique to achieve balance. Constrained randomization involves generating a large number of possible allocation schemes, calculating a balance score that assesses covariate imbalance, limiting the randomization space to a pre-specified percentage of candidate allocations and randomly selecting one scheme to implement. When the outcome is binary, a number of statistical issues arise regarding the potential advantages of such designs in making inference. In particular, properties found for continuous outcomes may not directly apply, and additional variations on statistical tests are available. Motivated by two recent trials, we conduct a series of Monte Carlo simulations to evaluate the statistical properties of model-based and randomization-based tests under both simple and constrained randomization designs, with varying degrees of analysis-based covariate adjustment. Our results indicate that constrained randomization improves the power of the linearization F-test, the KC-corrected GEE t-test (Kauermann and Carroll, 2001, Journal of the American Statistical Association 96, 1387–1396) and two permutation tests when the prognostic group-level variables are controlled for in the analysis and the size of randomization space is reasonably small. We also demonstrate that constrained randomization reduces power loss from redundant analysis-based adjustment for non-prognostic covariates. Design considerations such as the choice of the balance metric and the size of randomization space are discussed.

Keywords: group-randomized trial, constrained randomization, permutation test, generalized linear mixed model, generalized estimating equations

1. Introduction

Group-randomized trials (GRTs) are designed to evaluate the effect of an intervention that is delivered at the group level, due to logistical, political or administrative reasons [1, 2, 3, 4]. This design is characterized by allocating groups such as hospitals, clinics or worksites to comparison arms. In addition, GRTs are also frequently used to capture both direct and indirect intervention effects at the population level (e.g. related to herd immunity in the infectious diseases literature) [5]. Usually individuals from the same group tend to have more similar responses than individuals from different groups, because each group is not formed at random but rather through some social connections among its members; this similarity among observations taken within the same group can be quantified by the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) [6]. Yet a common practical limitation to the use of GRTs is the ability to enroll a large number of groups. With only a limited number of often heterogeneous groups, simple randomization may not adequately balance important group-level prognostic covariates between arms [7, 8]. For example, clinics within a health system may vary with respect to whether they treat primarily low-income patients, whether they are located in an urban area, and whether practice patterns differ. Statistical methods that control for baseline prognostic group-level characteristics in the design or analysis of a trial are necessary and a comprehensive understanding of the operating characteristics of adjustment methods is needed to appropriately plan a study.

Design-based covariate adjustment provides a foundation for causal inference by enhancing the baseline comparability of arms [9]. At the design stage of GRTs with a few groups, a number of baseline covariates may be available, but simultaneously balancing them via traditional design-based strategies, such as stratification or matching, come with limitations. Stratification may create sparse strata with a few groups and may balance only a handful of covariates [10], while matching represents extremely fine stratification and complicates the calculation of ICC, which should be reported for all GRTs [11]. Covariate-based constrained randomization [12] overcomes these limitations by simultaneously balancing multiple covariates to ensure that the comparison arms have similar baseline covariate distributions (internal validity). Briefly, this methodology includes (i) specifying important prognostic group-level or individual-level covariates (if available before randomization); (ii) characterizing each prospective group in terms of these covariates; (iii) either enumerating all or simulating a large number of potential allocation schemes; (iv) removing the duplicate allocation schemes if any, and (v) choosing a constrained space containing a subset of schemes where sufficient balance across covariates is achieved according to some pre-defined balance metric. Ultimately, one scheme is randomly selected out of this constrained space and allocation of groups is made accordingly. Raab and Butcher [13] first introduced an l2 balance metric and illustrated its use in a school-based GRT under constrained randomization. However, they did not fully characterize the statistical implications of using such designs to test for an intervention effect. To offer a better understanding of such designs, we investigate how constrained randomization, as a design-based adjustment technique, affects statistical inference in GRTs with a few groups per arm and binary outcomes.

Analysis-based adjustment for prognostic covariates often leads to increased estimation precision and testing power [14]. When implementing analysis-based adjustment, it is as important to specify which covariates will be adjusted for, as to detail the choice of a proper primary analytical method. Importantly, it is recommended that covariates used in design-based adjustment (i.e. matching, stratification or constrained randomization) should be accounted for in the analysis in randomized clinical trials [15]. However, Wright et al. [16] reviewed a random sample of 300 GRTs published from 2000 to 2008 and reported discrepancies on analysis-based covariate adjustment across studies. Among the 174 GRTs that used design-based covariate adjustment, only 30 (17.2%) studies reported an analysis adjusting for all the covariates balanced by randomization. Given the existing discrepancies in statistical practice, we reinforce the general recommendation on analysis-based covariate adjustment in the context of small GRTs. Motivated by two recent GRTs with binary outcomes, we focus on constrained randomization designs and compare, using simulations, different analytical methods to test for an intervention effect: two mixed-model F-tests, three bias-corrected GEE t-tests and two randomization-based permutation tests. In GRTs with binary outcomes, Austin [17] compared the power of several statistical methods, but his findings were limited to simple randomization and no covariates were assumed. Li et al. [18] compared the F-test and the permutation test under constrained randomization, but their findings were specifically for Gaussian outcomes and might not be easily generalizable to binary outcomes, due to the additional complexities in the analytical methods for such outcomes. The work presented in the current paper can be viewed as an extension of the work by Austin [17] and Li et al. [18]. Specifically, our first aim is to determine whether constrained randomization improves the power of several tests compared with simple randomization, while maintaining their nominal test sizes. Design parameters including the choice of balance metric and the size of randomization space are discussed and their implications are assessed by simulations. Another equally important aim is to investigate proper analysis-based covariate adjustment under constrained randomization, including specification of covariates to be adjusted for as well as the choice of analytic method.

The remainder of the paper is organized into five sections. In Section 2, we use two real studies to illustrate the constrained randomization design. In Section 3, we describe the details of hypotheses testing approaches for correlated binary outcomes arising from GRTs. Our simulation study and associated results are presented in Section 4 and 5. Section 6 gives concluding remarks.

2. Motivating examples

2.1. Constrained randomization design

With a pre-determined set of covariates to balance, we characterize the constrained randomization design by the choice of a balance metric and the size of randomization space. A balance metric calculates a balance score to assess covariate differences under each possible allocation scheme. Researchers have the flexibility to devise any sensible balance metric for their studies, which is an additional advantage of using constrained randomization. For example, Raab and Butcher [13] considered an l2 balance metric for a two-arm GRT

| (1) |

where ωk ≥ 0 is the weight for the kth variable considered for balance and x̄Tk, x̄Ck denote the average of the kth group-level covariate from two comparison arms. One can specify values of ωk to up-weight or down-weight certain baseline covariates to reflect different priorities; for example, some covariates may be thought to have a stronger association with the outcome, if prior knowledge is available. Otherwise, ωk is by default set to be the inverse variance of the group means for the kth covariate. This l2 metric accommodates both continuous and categorical variables (dummy variables are used to represent a multi-category factor), and is invariant to linear transformations of covariates with the default choice of ωk. Two alternative balance metrics were developed with constrained randomization [18, 19], but they were specifically designed to balance group-level factors and may not accommodate continuous variables. To compare with the l2 metric, we propose an l1 analog

| (2) |

where x̄Tk, x̄Ck and ω̃k are defined similarly, and by default ω̃k is taken to be the inverse standard deviation of the group means. Similar to the l2 metric, the l1 metric accommodates both continuous and categorical covariates and is invariant under linear transformations of covariates with the default choice of ω̃k.

Once a balance metric is specified, one can obtain the set of pairs {(Ir, Br) : r = 1, …, R} with Ir, Br denoting the rth allocation scheme and its balance score, and R representing the maximum number of distinct schemes under complete enumeration or random simulation. The size of randomization space q ∈ (0, 1] is defined to be the percentile such that a constrained randomization space is specified by , where is the inverse empirical distribution function of the balance scores, and R′ ≤ R is the number of distinct schemes retained in the constrained space. The size of randomization space q approximately measures the proportion of schemes achieving adequate covariate balance. When 0 < q < 1, 𝒞q is a subset of the complete space containing all allocation schemes 𝒮 = {Ir : r = 1, …, R}. When q = 1, 𝒞q = 𝒮 and the constrained randomization design becomes the simple randomization design. For example, suppose there are possible allocation schemes with a total of 16 groups assigned to two arms in a one-to-one ratio. When q = 0.1, the constrained randomization space contains around 1287 schemes (possibly with ties in the calculated balance scores) corresponding to the lowest balance scores. When q = 1, we have the simple randomization design because all 12870 schemes are kept in the randomization space by definition. We next illustrate the constrained randomization design using two GRTs.

2.2. The R/R immunization study

The reminder/recall (R/R) immunization study is an ongoing pragmatic GRT comparing a collaborative centralized (CC) R/R approach with a practice-based (PB) R/R approach for increasing the immunization rate in 19 to 35 month old children from 16 counties in Colorado [20]. Eight counties are randomized to each of the two R/R approaches. The CC approach depends on collaborative efforts between health department leaders and primary care physicians to develop a centralized R/R notification, either using telephone or mail, for all parents whose pre-school children are not up-to-date on immunization. Parents from the PB arm are invited to attend a web-based training on R/R using the Colorado Immunization Information System (CIIS). Although counties are the randomization unit, the binary outcome, immunization status, is to be collected for all contacted children.

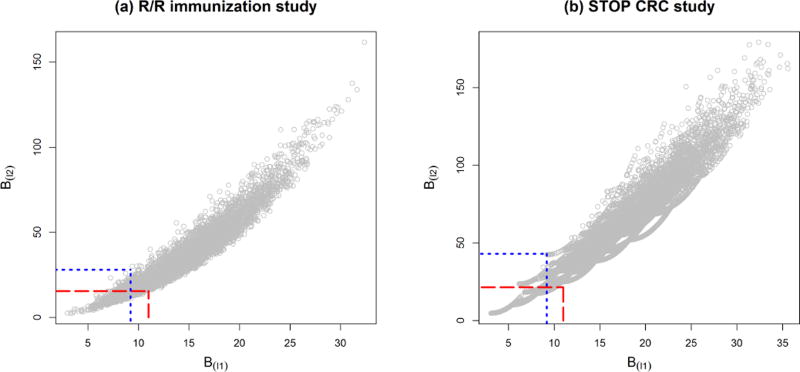

A pre-selected set of nine county-level covariates are balanced at the randomization phase, after which stage the participants will be enrolled in the study. These county-level variables are obtained from historical data in the U.S. Census and the Colorado Immunization Information System (CIIS). They are: whether a county is rural (coded as 1) or urban (coded as 0), number of Community Health Centers, ratio of pediatric to family medicine practices, percent of children between 0 to 4 months who had over 2 immunization records in CIIS, number of eligible children, percent up-to-date rate at baseline, percent Hispanic, percent African American and average income. Figure 1(a) is a scatter plot of the balance scores from the l2 metric against those from the l1 metric with default weights. The constrained randomization space with q = 0.1 under each balance metric is indicated in the plot. Each constrained space reduces the likelihood of county-level covariate imbalance by selecting the most balanced allocation schemes from the complete space 𝒮.

Figure 1.

Plots of balance scores from the l2 metric against balance scores from the l1 metric in (a) the R/R immunization study and (b) the STOP CRC study. The two constrained randomization spaces (q = 0.1) with l2 metric and with l1 metric are marked by the long-dashed red lines and the dotted blue lines, respectively.

2.3. The STOP CRC study

The Stop Colorectal Cancer (STOP CRC) study is an on-going pragmatic GRT allocating 26 federally qualified health clinics in a one-to-one ratio to usual care or an active intervention designed to increase colorectal cancer screening [21]. The active intervention involves an automated, data-driven and EHR-embedded program for mailing fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) kits with pictographic instructions to patients due for colorectal cancer screening. Patients are only provided opportunistic colorectal cancer screening in the usual care arm. The patient-level binary outcome, completion status of FIT within a year of study initiation, is to be collected as the primary outcome.

Two clinic-level covariates, the baseline national quality forum (NQF) score and the health center (HC), are available at the randomization phase, after which patients will be enrolled. The NQF score is a measure of the proportion of population that is already compliant with colorectal cancer screening; the HC identifies larger administrative networks into which the clinics are grouped. The NQF score is a continuous measure, and the HC is a factor with 8 levels. Simple stratified randomization is no easy task to simultaneously balance a continuous variable and a multi-level factor, so the constrained randomization design is a recommended option. Figure 1(b) marks the constrained randomization space with q = 0.1 under each balance metric. The more balanced schemes enter the constrained randomization space and hence reduce the likelihood of chance baseline covariate imbalance.

3. Testing intervention effect in group-randomized trials with binary outcomes

In this section, we review theory on both the model-based and randomization-based tests of the intervention effect in GRTs with binary outcomes. For clarity of presentation, we assume a total of 2g groups are randomized into two arms in a one-to-one ratio. Let Ti = 1 if group i is assigned to intervention and zero otherwise, and write xij as the p-dimensional vector of group-level or individual-level covariates from individual j (j = 1, …, ni) nested in group i (i = 1, …, 2g). Of note, this vector may contain both group-level and individual-level covariates, although individuals from the same group necessarily take identical values for the group-level covariates. Further, if this vector only includes group-level covariates, we could simply replace xij by xi and the rest follows.

3.1. Mixed-model F-tests

The GLMM with a logistic link function and adjustment for baseline covariates is expressed by

| (3) |

where the outcomes are independently distributed as yij ~ Bernoulli(πij) conditional on γi and where the within-group correlation is accounted for by a group-specific Gaussian random effect . In the model, μ is the log odds of a positive outcome (yij = 1) for control subjects (Ti = 0) with reference values for covariates (xij = 0) and an “average” random effect (γi = 0). Here, δ is the intervention effect, and β is the vector of covariate effects. The model-based test for H0 : δ = 0 uses a Wald-type F-statistic with its null distribution F(1,DDF), where DDF stands for denominator degrees of freedom. We review two methods to estimate the intervention effect δ and its variance, from which we obtain two F-tests. The two tests are referred to as the linearization F-test and the likelihood F-test.

The first approach, to generate the linearization F-test, uses a linearization technique [22] to approximate the logistic GLMM by a linear mixed model (LMM), and constructs the test based on theory developed for the linear mixed models. Specifically, given a current estimate for θ̃ = (μ̃, δ̃, β̃′)′ and γ̃ = (γ̃1, …, γ̃2g)′, a first-order Taylor expansion of the probability vector π = (π11, …, π2g,n2g)′ about θ̃ and γ̃ induces a linear mixed model with a vector of pseudo-responses Ỹθ̃, γ̃. The model parameters are then estimated from the induced LMM by maximizing the restricted pseudo-likelihood. Restricted likelihood rather than unrestricted likelihood is selected in order to reduce bias in parameter estimates for the variance components [23]. The current estimates from the induced LMM are subsequently used to update the pseudo-responses, which will be used to re-estimate model parameters in the induced LMM. This iterative process stops when the parameter estimates between successive updates are close enough; the final linear mixed model produces the restricted maximum likelihood estimate (REML) θ̂ and its covariance, which gives the F-statistic.

The second estimation approach, to generate the likelihood F-test, proceeds with the true binomial likelihood and numerically evaluates the marginal likelihood to obtain the maximum likelihood estimates (MLE). In model (3), the marginal likelihood of the binary outcomes integrates out the random effects γi, and leads to the following log-likelihood:

| (4) |

where is the mean zero Gaussian density with variance . Closed-form solutions to the MLE cannot be obtained and therefore numeric approximation to the integral-based log-likelihood is carried out by Gaussian quadrature [24], after which the MLE δ̂ is obtained by applying the Newton-type technique to optimize the approximate log-likelihood. The variance for δ̂ is calculated from the inverse Fisher information of the approximate likelihood.

Even in cases of complex GLMMs such as those with correlated errors or a large number of random effects, the linearization approach is a computationally efficient algorithm and has competitive performance, while the likelihood approach may become infeasible due to demanding computations, although the latter generally produces more accurate parameter estimates with sufficient number of groups [7]. To determine the null F-distribution in GRT applications, Li and Redden [25] compared five DDF approximations for testing the intervention effect with 10 to 30 groups under simple randomization. They reported that only the F-test using the between-within DDF approximation [26] consistently preserved the nominal type I error rate. In model (3), the between-within DDF is 2g − (p1 + 2), namely the difference between the number of groups and the number of group-level parameters.

3.2. Bias-corrected GEE t-tests

An alternative testing framework for correlated binary data is based on generalized estimating equations (GEE) [27]. In contrast to GLMM, GEE account for within-group homogeneity by directly modelling the correlation structure of the outcomes [28]. Specifically, we specify a marginal logistic regression by omitting the random effects γi in model (3),

| (5) |

and supply a “working” correlation matrix describing the degree of similarity between responses within groups. In GRT applications, the exchangeable correlation structure is frequently used, i.e., the same correlation parameter is assumed for all pairs of individuals from the same group. Note that this correlation parameter corresponds to the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). The intervention effect estimate δ̂ is then obtained by solving the GEE, a multivariate analog of the quasi-score function [29]. The GEE Wald-type t-test is based on the statistic , which under δ = 0 follows an approximate t-distribution with 2g − (p1 + 2) degrees of freedom [30]. Although the robust sandwich estimator is routinely used to estimate var(δ̂), it tends to underestimate the variability of the intervention effect with limited groups, and a class of bias-corrected sandwich estimators have been developed with improved test sizes [30, 31, 32, 33, 34]. We estimate var(δ̂) using the bias-corrected sandwich estimators proposed by Mancl and DeRouen [30], Kauermann and Carroll [31], Fay and Graubard [32], and name the associated tests as MD-corrected, KC-corrected and FG-corrected GEE t-tests, respectively. Under simple randomization, several simulation studies [35, 36] have compared these bias-corrected t-tests for intervention effect without additional covariates; they found that the MD-corrected t-test tends to be conservative, and either the KC-corrected or the FG-corrected t-test is preferable depending on the degree of group size variability. One study considered scenarios with covariates other than the treatment variable and found that the KC correction is preferable [37]. Extending the previous studies, we examine these bias-corrected t-tests under constrained randomization with covariates in addition to the treatment variable.

3.3. Randomization-based tests

First introduced by Fisher [38], the permutation test (P-test) presents a robust alternative to the model-based methods in GRTs. In general, the outcome data are first analyzed based on the actual observed group allocation. Then the observed test statistic is referenced against its exact permutational distribution calculated from all possible allocation schemes [39, 40]. The two-sided p-value is defined as the proportion of the test statistics obtained by permutation that are as large or larger than the observed one. We review two randomization-based test procedures, which we refer to as the residual P-test and the likelihood P-test. Gail et al. [41] proposed a permutation test based on the residuals computed by fitting model (5) assuming independence working correlation and δ = 0. Denote the residual for each individual by rij and the residual mean in group i by , the test statistic is defined to be

| (6) |

Note that under the null hypothesis δ = 0, the 2g group-specific residual means are exchangeable under the condition of equal group size [41]. The observed test statistic is computed using (6) according to the observed allocation scheme. Due to exchangeability of the residual means, the permutational distribution of Sresidual can be obtained by calculating (6) under all possible randomization schemes, or equivalently, by shuffling the values of Ti. The two-sided exact p-value is then determined using the observed test statistic and its permutational distribution. Gail et al. [41] used simulations to demonstrate the validity of this residual permutation test under simple randomization as long as there is an equal number of groups assigned to each comparison arm (design balance at the group level). Of note, this test has a much simpler form without covariate adjustment, in which case each rij in the test statistic reduces to the difference between yij and the overall mean ȳ‥, leading to Sresidual = g−1 Σi(2Ti − 1)(ȳi․ − ȳ‥) = g−1Σi(2Ti − 1)ȳi․.

Braun and Feng [42] devised a permutation test based on the score function of δ from the GLMM (3) and demonstrated its validity under simple randomization. This test depends on the true marginal likelihood of the data, and is the locally most powerful permutation test when the GLMM is correct. The likelihood P-test proceeds in a similar fashion as the residual P-test, although with a more complicated test statistic. In the first stage, we fit the GLMM (3) assuming δ = 0 to initialize the remaining model parameters, so that each πij can be explicitly expressed as a function of the corresponding random effect γi. Then we use πij = πij(γi) to compute the test statistic under the observed allocation scheme by

| (7) |

This test statistic is obtained as the first-order derivative of the log-likelihood (4) with respect to δ and involves only one-dimensional integrals (see Web Appendix A for a derivation). Similar to the model-based likelihood approximation, each single integral can be numerically evaluated through Gaussian quadrature. Next the permutational distribution is obtained by evaluating equation (7) according to every possible scheme in the specified randomization space. Compared to the model-based approaches which rely on some pre-specified variance estimators to approximate the sampling distribution, the randomization-based approaches obtain the sampling distribution by replicating the same random process as used in the simple or constrained allocation process and tend to be more robust. However, on the other hand, it is often computationally intensive to compute confidence intervals from the permutation approaches [42], while the model-based confidence intervals are readily available from standard software output.

4. Methods for the simulation studies

We conducted a series of simulations based on a cross-sectional design with a single binary outcome yij for each individual j (j = 1, …, ni) nested within each group i (i = 1, …, 2g). We assumed a two-arm trial, with g groups randomized to each arm. Mimicking the structure of the motivating examples, we used g = 8 and g = 13 to determine whether the comparison of tests depended on the number of groups. Each group was assumed to contain ni = 250 individuals, which is typical of school- or worksite-based GRTs [43]. Although both the R/R vaccination study and the STOP CRC study have larger group sizes, we chose this number for computational efficiency concerns. Also, it is well known in GRTs that the effective sample size is largely determined by the number of groups and only marginally by the group sizes [2]. When we performed additional simulations using group sizes of 500 and 1500, our findings remained similar but the computational time was prohibitive. In order to resemble the motivating examples, we assumed that there were no individual-level covariates and instead focused on adjustment for group-level covariates both in the design and in the analysis. Individual-level covariates, which are collected after randomization when participants are recruited, could be controlled for in the primary analysis but are typically not available in the design phase. We defer discussions about individual-level covariates to Section 6.

4.1. Data generation

The outcome yij was generated from Bernoulli(πij), where the event probability πij was specified by with . We set the intercept μ = −1 so that the event probability for an individual from an “average” group with covariate profile xi = 0 was approximately 25%. Depending on the realized randomization scheme, the indicator variable Ti = 1 if group i was assigned to intervention and Ti = 0 otherwise. The intervention effect δ was fixed at zero for studying type I error and was fixed at 0.5 for studying power (corresponding to an intervention odds ratio of approximately 1.65). We considered four group-level covariates, represented by the 4-dimensional column vector xi. Each group-level covariate was independently simulated from a Bernoulli distribution with probability 0.3 (a modest probability of being either 1 or 0). Examples of binary group-level covariates include whether the group is associated with a teaching hospital, its geographic region (possibly represented by more than one binary covariate), or aggregated patient characteristics from previous studies such as low versus high average age or income. The extension to continuous group-level covariates is straightforward, therefore we present binary group-level covariates for illustration purposes. Although in practice we aim to balance important covariates during randomization, we may not have information on whether the variables controlled for by design are truly predictive of the outcome. Therefore, it is important to understand the implications of balancing both prognostic and non-prognostic group-level variables by constrained randomization. For this reason, we consider two scenarios. First, we set β = 14×1 to indicate scenarios where the group-level covariates are prognostic. Second, we considered β = 04×1 to represent situations where these covariates are non-prognsotic. The variance component was chosen to reflect the desired ICC value ρ defined to be , where Π ≈ 3.142 is the exponential mathematical constant [6]. This definition of ICC employs the latent response representation of the GLMM and is used here to measure the degree of similarity or clustering among observations taken within the same group. Three levels of ICCs were considered for each level of g: 0.001, 0.01, and 0.05. A trivial clustering scenario was represented by ρ = 0.001, and the other two values of ρ were among those commonly reported in GRTs [2, 7, 44]. We considered two-sided tests throughout with a nominal size of 0.05. To ensure stable estimates of type I error and power, we generated 3000 Monte Carlo replicates for each combination of parameters. In summary, we considered a factorial simulation study design of 3 values of ICC × 2 numbers of groups × 2 types of covariates (prognostic and non-prognostic).

4.2. Design-based versus analysis-based adjustment

We considered design-based adjustment for group-level covariates xi by constrained randomization, which we compared to simple randomization (i.e. no design-based adjustment). For each scenario determined by g, simple randomization selected the final allocation scheme irrespective of the information from the group-level covariates. For constrained randomization scenarios, all potential randomization schemes were first enumerated (for g = 8) or a large number were simulated (for g = 13). Then the intervention was implemented by a randomly selected allocation scheme from the randomization subspace where sufficient balance was achieved according to either the l1 or l2 balance metric with default weights. Since the purpose of using covariate-based constrained randomization is to simultaneously balance multiple covariates, we considered balancing all four group-level covariates under the constrained randomization design for each of the two balance metrics. We give simple matrix expressions to efficiently calculate the balance scores in Web Appendix B. Under g = 8, a complete enumeration of the 12870 randomization schemes is computationally feasible. With g = 13, we randomly sampled 20000 schemes and removed duplicates to approximate the complete randomization space since full enumeration would lead to intractable computation. The balance scores were then calculated using the matrix expressions corresponding to the enumerated or, in the case of g = 13, the randomly sampled schemes. Because the absolute magnitude of balance score has no intuitive meaning, we ensured acceptable balance, for each of the two balance metrics, by specifying the size of randomization space corresponding to the smallest values of B(l1) or B(l2). Specifically, we let q = 1 to indicate simple randomization and let q ∈ {0.5, 0.3, 0.1, 0.05, 0.01} to indicate constrained randomization.

For both simple and constrained randomization, we compared the tests reviewed in Section 3. All data replicates were created in R (http://www.r-project.org), as were programs for conducting the P-tests; we used the Gaussian quadrature method provided by [45] to numerically approximate the test statistic (7) under the observed allocation scheme and its permutational distribution. Analyses with the mixed-model F-tests and GEE t-tests were performed in SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC). Specifically, the GLIMMIX procedure was used for the linearization F-test and the bias-corrected GEE t-tests, and the NLMIXED procedure was used for the likelihood F-test. Example SAS code to implement the model-based tests is available in Web Appendix C. For each test, we compared unadjusted and adjusted versions to evaluate the impact of analysis-based adjustment beyond design-based adjustment for covariates. Note that in our simulations the adjustment is with respect to the covariates available prior to randomization, i.e., the group-level covariates xi. We let S denote the number of group-level covariates controlled for in the analysis. Then S = 0 simply indicates an unadjusted test while S ≥ 1 implies a test adjusting for S group-level covariates.

5. Results from the simulation studies

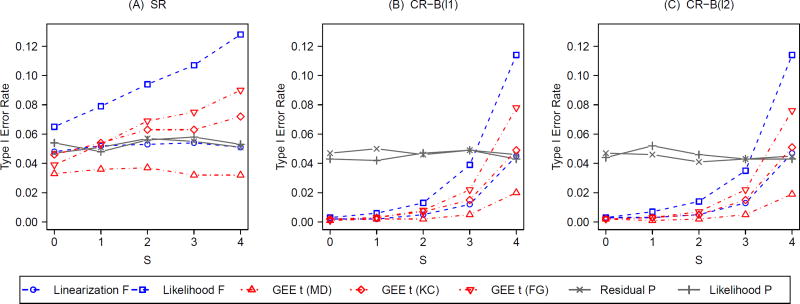

5.1. Type I error – balancing prognostic covariates

Figure 2 summarizes the Monte Carlo type I error rates for the tests under simple randomization (SR) and constrained randomization (CR), with g = 8 and different values of S. To simplify the presentation, we fix the ICC at 0.05 and choose the size of randomization space q = 0.1 for all CR scenarios. All four group-level covariates are assumed prognostic and are adjusted for in the constrained randomization designs. For analysis-based adjustment, when S = 0, no covariates are controlled for in the analysis and therefore an unadjusted test is used; an adjusted test further controls for S (S ≥ 1) group-level covariates. Results from CR using the l1 (panel B) and l2 (panel C) balance metrics are contrasted with those from SR (panel A).

Figure 2.

Type I error rates with varying degrees (S) of analysis-based adjustment for prognostic group-level covariates under constrained randomization (CR) with 2 balance metrics (B(l1) and B(l2)) versus simple randomization (SR); g = 8, ICC = 0.05; q = 0.1 under CR.

Under CR, the mixed-model F-tests and bias-corrected GEE t-tests become conservative with insufficient analysis-based covariate adjustment (S ≤ 3). In particular, the type I error rate approaches zero for these model-based tests under CR. With sufficient analysis-based adjustment (S = 4), the linearization F-test and the KC-corrected GEE t-test maintain the desired type I error rate, whereas the likelihood F-test and the FG-corrected GEE t-test grow anti-conservative. In fact, unlike the linearization F-test which consistently preserves the nominal size under SR across all levels of S, the likelihood F-test is liberal under SR. This phenomenon signals the limitation of asymptotic likelihood theory in small samples. With g = 8, the sample size is rather small, so a large-sample approximate test is not guaranteed for a correct size. However, the linearization F-test depends on the induced LMM and REML, demonstrating better control of type I error. Although the KC-corrected GEE t-test tends to be slightly anti-conservative under SR (S ≥ 2), it carries the correct size under CR with sufficient analysis-based adjustment (S = 4). Similar to the previous report [36], the MD-corrected GEE t-test is conservative throughout. A different and better pattern is observed for both P-tests: they behave similarly and both carry the desired type I error rates at all levels of S, without regard to the randomization design. Of note, there is little to no impact of the balance metric used in CR scenarios regarding type I error and no real benefit of additional analysis-based adjustment after the design-based adjustment (panels B and C). Similar patterns are found with g = 13 (Web Figure 1) and other choices of q (results not shown).

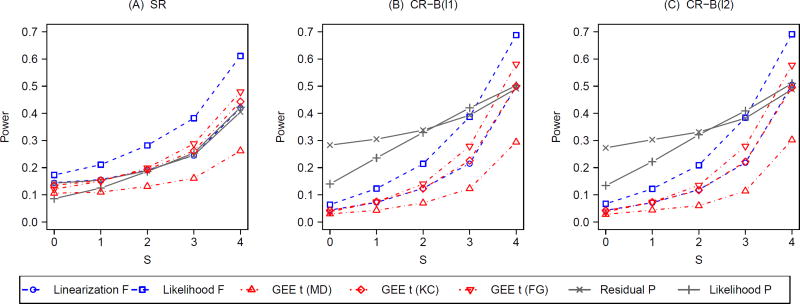

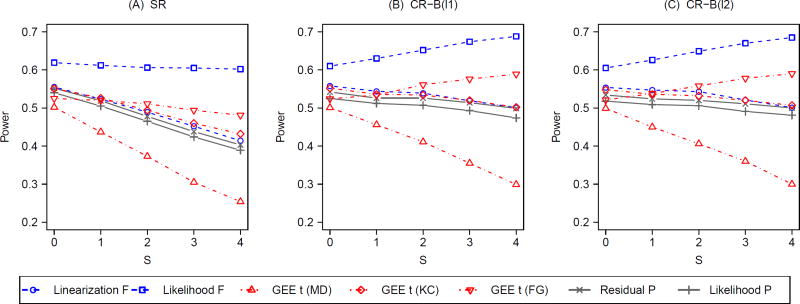

5.2. Power – balancing prognostic covariates

Figure 3 summarizes the results on power corresponding to Figure 2 with g = 8. A general pattern is that all tests improve power with increasing S, indicating the utility of analysis-based adjustment for prognostic group-level covariates under both SR and CR. More concrete results are outlined as follows. Without adjusting for the prognostic covariates (S = 0), all mixed-model F-tests and bias-corrected GEE t-tests slightly reduce power under CR compared to those under SR. In contrast, both unadjusted P-tests (S = 0) improve power under CR relative to SR. With S = 0, the residual P-test is slightly more powerful than the likelihood P-test under SR, but the former is more than twice as powerful as the latter under CR. However, this power gain from the design-based adjustment does not reach the level attained by the analysis-based adjustment when all prognostic covariates are adjusted for. For the fully-adjusted linearization F-test, fully-adjusted GEE t-test with KC correction, and the two fully-adjusted P-tests, there is additional power gain from design-based adjustment using CR, although this power increase is marginal with limited sample size (g = 8, ICC= 0.05). The highest power is achieved by the fully-adjusted likelihood F-test (S = 4), but we need to exercise some caution about its interpretation since this test fails to maintain the nominal size regardless of randomization designs. Under SR, the residual P-test, the linearization F-test and the KC-corrected GEE t-test have similar power across all levels of S, but the likelihood P-test is less powerful with S ≤ 1. Under CR, both permutation tests have higher power than the linearization F-test and the KC-corrected GEE t-test when S ≤ 3 and their powers are all nearly equal when S = 4. This observation indicates that the optimal power is achieved by combing design-based and analysis-based control for prognostic covariates, irrespective of the choice of a valid test. Similar to Figure 2, the choice of balance metric does not make a substantial difference under CR concerning power. The same patterns are observed with g = 13 (Web Figure 2) and other choices of q (results not shown).

Figure 3.

Power with varying degrees (S) of analysis-based adjustment for prognostic group-level covariates under constrained randomization (CR) with 2 balance metrics (B(l1) and B(l2)) versus simple randomization (SR); g = 8, ICC = 0.05; q = 0.1 under CR.

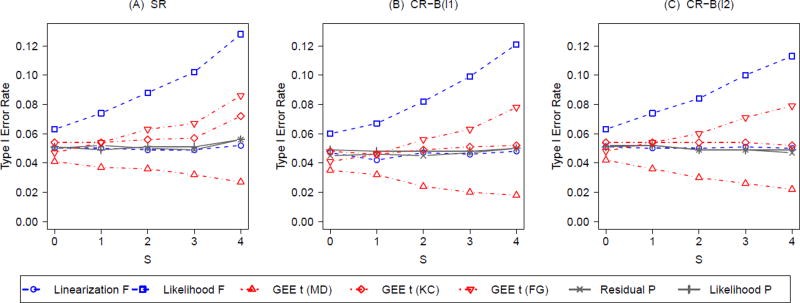

5.3. Balancing non-prognostic covariates

We now present the results when the group-level covariates are non-prognostic, so that β = 0 in the data generating process. We summarize the type I error and power results under such scenarios in Figure 4 and 5, respectively. Figure 4 parallels Figure 2 except that all the group-level covariates are no longer associated with the outcome. Under CR, a notable difference from Figure 2 is that the linearization F-test and the KC-corrected GEE t-tests now maintain the nominal size across all levels of S. This observation indicates that constrained randomization does not alter the size of the above two tests by balancing non-prognostic group-level covariates, regardless of whether these covariates are controlled for by the testing procedures. In fact, combining the results from Figure 2, we find out that both the linearization F-test and the KC-corrected GEE t-test are valid as long as the prognostic covariates balanced by CR are adjusted for in the analysis, even though the KC-corrected GEE t-test tends to be liberal under SR (S ≥ 2). Similar to Figure 2, both P-tests maintain the nominal sizes. Little evidence is found to favor one balance metric over the other under CR with regard to type I error; similar results are found for g = 13 (Web Figure 3) and other choices of q (results not shown).

Figure 4.

Type I error rates with varying degrees (S) of analysis-based adjustment for non-prognostic group-level covariates under constrained randomization (CR) with 2 balance metrics (B(l1) and B(l2)) versus simple randomization (SR); g = 8, ICC = 0.05; q = 0.1 under CR.

Figure 5.

Power with varying degrees (S) of analysis-based adjustment for non-prognostic group-level covariates under constrained randomization (CR) with 2 balance metrics (B(l1) and B(l2)) versus simple randomization (SR); g = 8, ICC = 0.05; q = 0.1 under CR.

Figure 5 parallels Figure 3 except for that all the group-level covariates used in data generation are not associated with the binary outcomes. We limit our discussions here to the linearization F-test, KC-corrected GEE t-test and the two P-tests since the other tests carry incorrect type I error rate. Under SR, these four tests decrease power with increasing S. Particularly, the value of S can be regarded as the degree of covariate over-adjustment in the analysis, and the power of the test declines by including more irrelevant covariates. With only 16 groups and ICC= 0.05, the power difference between the correct model (S = 0) and the worst model (S = 4) is as large as 15%. Nevertheless, this power difference due to over-adjustment shrinks to less than 5% under CR with either balance metric. Combined with the results in Figure 3, the results in Figure 5 imply that constrained randomization doesn’t reduce power of these four tests as long as the prognostic covariates balanced by the CR design are accounted for in the analysis. We offer two comments underlying this point.

From the design aspect, CR should be advocated over SR since it improves power of an appropriate analysis. From the analysis aspect, an appropriate analysis under CR should adjust for those balanced covariates that are believed to affect the outcome for potential power gain. Although the power loss resulting from over-adjustment is greatly reduced under CR compared to SR, this power loss is not eliminated under CR, and carefully selecting covariates for analysis-based adjustment remains a crucial task. Little difference is found between the two balance metrics under CR regarding power; similar results are found for g = 13 (Web Figure 4).

5.4. Size of randomization space

To characterize the influence of size of randomization space q, we present the Monte Carlo type I error rates and power for the four tests of Tables 1 and 2 (i.e. linearization F-test, KC-corrected GEE t-test, residual P-test and likelihood P-test; the other tests were not shown because of their incorrect type I error). We assume that the group-level covariates are associated with the outcomes (i.e. are prognostic); the presentation is limited to the l2 metric under CR since the results for the l1 metric are no different. Included in each table are the unadjusted (S = 0) and the fully-adjusted (S = 4) versions of each test. Table 1 summarizes the type I error rates under different randomization scenarios with g = 13. The different CR scenarios are described by the values of q. The results are compared with the SR scenario (q = 1), whose randomization space includes allocation schemes. Under SR, all tests approximately maintained the nominal size, except that the fully-adjusted linearization F-test becomes slightly conservative under “trivial clustering” of outcomes (ICC= 0.001). More conservative results are observed with g = 8 in Web Table 1. Under CR, the fully-adjusted linearization F-test carries the correct size (except for slight conservativeness under ICC= 0.001), while the unadjusted version grows conservative, indicating the necessity of analysis-based adjustment for prognostic covariates already balanced by design. Although the fully-adjusted GEE t-test with KC correction has the correct size with g = 13 under both SR and CR, it only maintains the nominal size under CR and tends to have an inflated type I error rate under SR with g = 8 (Web Table 1). Notably, both P-tests, whether unadjusted or adjusted, preserve the nominal type I error under both SR and CR and at all levels of ICC. To conclude, the size of randomization space has no effect on the size of a valid test. The type I error results for g = 8 are similar and summarized in Web Figure 1.

Table 1.

Type I error rates for the unadjusted (S = 0) and fully-adjusted (S = 4) tests under simple versus constrained randomization with g = 13. The l2 balance metric is used by constrained randomization; the group-level covariates are assumed prognostic.

| Linearization F | GEE t (KC) | Residual P | Likelihood P | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| ICC | Randomization | q | S = 0 | S = 4 | S = 0 | S = 4 | S = 0 | S = 4 | S = 0 | S = 4 |

| 0.01 | 0.000 | 0.034 | 0.000 | 0.049 | 0.046 | 0.046 | 0.048 | 0.045 | ||

| 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.034 | 0.000 | 0.049 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.043 | 0.048 | ||

| Constrained | 0.10 | 0.000 | 0.039 | 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.045 | 0.053 | 0.045 | 0.053 | |

| ρ = 0.001 | 0.30 | 0.000 | 0.039 | 0.000 | 0.052 | 0.056 | 0.049 | 0.055 | 0.050 | |

| 0.50 | 0.000 | 0.041 | 0.001 | 0.055 | 0.048 | 0.053 | 0.047 | 0.053 | ||

| Simple | 1.00 | 0.053 | 0.034 | 0.052 | 0.050 | 0.055 | 0.044 | 0.053 | 0.044 | |

| 0.01 | 0.000 | 0.048 | 0.000 | 0.051 | 0.047 | 0.047 | 0.049 | 0.046 | ||

| 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.047 | 0.000 | 0.050 | 0.047 | 0.048 | 0.044 | 0.045 | ||

| Constrained | 0.10 | 0.000 | 0.049 | 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.042 | 0.050 | 0.047 | 0.051 | |

| ρ = 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.001 | 0.049 | 0.000 | 0.053 | 0.054 | 0.045 | 0.058 | 0.048 | |

| 0.50 | 0.002 | 0.048 | 0.001 | 0.051 | 0.047 | 0.050 | 0.048 | 0.048 | ||

| Simple | 1.00 | 0.052 | 0.050 | 0.051 | 0.057 | 0.054 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.048 | |

| 0.01 | 0.000 | 0.049 | 0.000 | 0.053 | 0.049 | 0.048 | 0.052 | 0.049 | ||

| 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.050 | 0.001 | 0.050 | 0.049 | 0.046 | 0.050 | 0.050 | ||

| Constrained | 0.10 | 0.000 | 0.053 | 0.000 | 0.054 | 0.047 | 0.051 | 0.051 | 0.053 | |

| ρ = 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.002 | 0.052 | 0.002 | 0.054 | 0.051 | 0.050 | 0.045 | 0.050 | |

| 0.50 | 0.008 | 0.050 | 0.006 | 0.057 | 0.046 | 0.053 | 0.052 | 0.050 | ||

| Simple | 1.00 | 0.053 | 0.047 | 0.052 | 0.058 | 0.054 | 0.048 | 0.051 | 0.049 | |

Table 2.

Power for the unadjusted (S = 0) and fully-adjusted (S = 4) tests under simple versus constrained randomization with g = 13. The l2 balance metric is used by constrained randomization; the group-level covariates are assumed prognostic.

| Linearization F | GEE t (KC) | Residual P | Likelihood P | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||

| ICC | Randomization | q | S = 0 | S = 4 | S = 0 | S = 4 | S = 0 | S = 4 | S = 0 | S = 4 |

| 0.01 | 0.023 | 1.000 | 0.028 | 1.000 | 0.764 | 1.000 | 0.452 | 1.000 | ||

| 0.05 | 0.062 | 1.000 | 0.065 | 1.000 | 0.812 | 1.000 | 0.464 | 1.000 | ||

| Constrained | 0.10 | 0.097 | 1.000 | 0.105 | 1.000 | 0.756 | 1.000 | 0.425 | 1.000 | |

| ρ = 0.001 | 0.30 | 0.152 | 1.000 | 0.158 | 1.000 | 0.558 | 1.000 | 0.337 | 1.000 | |

| 0.50 | 0.178 | 1.000 | 0.177 | 1.000 | 0.448 | 1.000 | 0.260 | 1.000 | ||

| Simple | 1.00 | 0.249 | 1.000 | 0.250 | 1.000 | 0.255 | 1.000 | 0.169 | 1.000 | |

| 0.01 | 0.033 | 0.998 | 0.037 | 0.998 | 0.720 | 0.998 | 0.406 | 0.998 | ||

| 0.05 | 0.074 | 1.000 | 0.074 | 1.000 | 0.756 | 1.000 | 0.402 | 1.000 | ||

| Constrained | 0.10 | 0.102 | 1.000 | 0.107 | 1.000 | 0.699 | 1.000 | 0.374 | 1.000 | |

| ρ = 0.01 | 0.30 | 0.156 | 0.998 | 0.154 | 0.997 | 0.530 | 0.998 | 0.294 | 0.998 | |

| 0.50 | 0.177 | 0.997 | 0.170 | 0.996 | 0.417 | 0.997 | 0.249 | 0.998 | ||

| Simple | 1.00 | 0.249 | 0.995 | 0.246 | 0.993 | 0.249 | 0.992 | 0.165 | 0.992 | |

| 0.01 | 0.050 | 0.789 | 0.053 | 0.764 | 0.477 | 0.753 | 0.215 | 0.786 | ||

| 0.05 | 0.084 | 0.759 | 0.085 | 0.745 | 0.531 | 0.741 | 0.221 | 0.766 | ||

| Constrained | 0.10 | 0.108 | 0.756 | 0.112 | 0.745 | 0.508 | 0.740 | 0.205 | 0.768 | |

| ρ = 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.143 | 0.771 | 0.141 | 0.746 | 0.408 | 0.744 | 0.173 | 0.779 | |

| 0.50 | 0.160 | 0.739 | 0.160 | 0.729 | 0.334 | 0.725 | 0.159 | 0.745 | ||

| Simple | 1.00 | 0.227 | 0.695 | 0.219 | 0.690 | 0.228 | 0.675 | 0.127 | 0.697 | |

Table 2 summarizes the power for the selected tests with g = 13. Each cell in Table 2 corresponds to a cell in Table 1. Four patterns are apparent. First, except for the two unadjusted model-based tests, larger ICC values lead to decreased power of a given test under both randomization designs. Second, the adjusted version of a test is more powerful than its unadjusted counterpart under CR, confirming the need of analysis-based adjustment for prognostic covariates that are already controlled for by design. Specifically, we observe that analysis-based adjustment dominates the design-based adjustment with respect to power gain. For example, this can be seen by comparing the unadjusted residual P-test under CR with q = 0.1 against the adjusted residual P-test under SR, at any level of ICC. Third, the unadjusted linearization F-test and KC-corrected GEE t-test decrease power with decreasing size of randomization space q; in fact, the linearization F-test and the KC-corrected GEE t-test (both unadjusted and adjusted) have very similar power performance. In contrast, both unadjusted P-tests gain power with a tighter randomization space. Of note, this power gain is not always monotonic; in other words, the power of a test may not continue to improve below a particular value of q. Moreover, the unadjusted residual P-test achieves higher power gain under CR compared to the unadjusted likelihood P-test, since the former test only uses the group-specific mean ȳi but the latter test adopts an incorrect mixed-model likelihood. Fourth, design-based adjustment of prognostic covariates still improves the power of an adjusted test, but this improvement is not substantial (e.g., <10% with q = 0.1 and ICC= 0.05). Similar patterns are observed with g = 8 (Web Table 2).

5.5. Small group sizes

To evaluate the use of the model-based tests in small GRTs where the group sizes are small, we compared the fully-adjusted linearization F-test, KC-corrected GEE t-test (S = 4) with the two fully-adjusted (S = 4) permutation tests under varying group sizes with g = 8. Web Figure 5 summarizes the results on type I error under SR (panel A) and CR (panel B). We consider a set of realistic values for the group size. For instance, if each class in a school is a randomization group, then 40 would be a reasonable value for the class size. We held ICC = 0.01 and q = 0.1 under CR to simplify the illustration. Under SR, the linearization F-test is conservative if the group size is below 120; the same trend is observed under CR that balances all four group-level prognostic covariates. Particularly, the type I error rate is around 3 percent with 40 individuals per group under both SR and CR. As the group size increases to 200, the type I error rate for the linearization F-test is held at 5 percent. Although the KC-corrected GEE t-test tends to be liberal under SR, its size becomes closer to the nominal value under CR with q = 0.1 for all levels of group sizes. On the other hand, both permutation tests maintain the correct size irrespective of the group sizes. In such cases where the group sizes are small, the exact permutation tests are recommended to avoid power loss from the linearization F-test and to protect against possibly inflated type I error rate associated with the KC-corrected GEE t-test.

6. Discussion

Constrained randomization is a promising tool in small GRTs for its ability to balance multiple covariates, and hence to reduce the likelihood of chance imbalance. In a previous simulation study [18], with continuous, normally distributed outcomes, we demonstrated that (i) under SR, the LMM F-test and the permutation test maintained the nominal type I error with or without adjustment; and (ii) under CR, the adjusted and the unadjusted permutation tests as well as the adjusted F-test carried the nominal type I error, whereas the unadjusted F-test became unacceptably conservative. We concluded that CR accompanied by a permutation test can offer design-based control of group-level covariates, even when unadjusted, although the adjusted test provides more power. Additionally, we noted the important caveat that the permutation test must be performed appropriately within the constrained randomization space to maintain its performance characteristics.

The current study, motivated by two recent GRTs, further evaluated the use of constrained randomization for the case of binary outcomes. We focused on balancing group-level covariates that are well characterized prior to randomization. We found that when the prognostic group-level covariates are balanced by design, both the model-based (linearization F-test, KC-corrected GEE t-test) and randomization-based analyses gain power and preserve test size, given proper adjustment for these covariates in the analyses. Notably, the advantage of design-based covariate adjustment is also reflected by the two unadjusted permutation tests, for which the power increases substantially as the size of the randomization space decreases, both for g = 8 and g = 13. On the other hand, if only non-prognostic group-level covariates are balanced by constrained randomization, the type I error rate and power of an unadjusted test are almost unaffected. Compared with simple randomization, constrained randomization improved the power of the tests adjusting for these non-prognostic covariates, and in a sense reduces power loss due to analysis-based covariate over-adjustment. However, with g = 8 and g = 13, the adjusted tests are still slightly less powerful than the unadjusted counterparts due to incorporating redundant non-prognostic covariates. These results indicate that constrained randomization by no means acts as a remedy for covariate over-adjustment in the analysis, and it should instead be regarded as the design-based enhancement for a correct analysis. We reinforce the recommendation to carefully select the covariates for balance under constrained randomization. Ideally, these covariates should be associated with the outcomes from prior knowledge to maximize the chance of power gain from constrained randomization. As noted by one reviewer, our findings also have implications for the simple two-sample t-test (based on the event rate in each group), which is sometimes used as an alternative to regression model-based tests for the analysis of GRTs. Although the two-sample t-test is robust under SR [17], it shares similar operating characteristics to the model-based tests because it depends on the variance estimator calculated assuming SR. Therefore, the two-sample t-test would be conservative if prognostic baseline covariates are balanced by CR. Since the null distribution of the t-statistic is hard to obtain analytically under CR, we could use the permutational distribution of the test statistic for valid inference.

Although it is not the case in our motivating examples, there could be trials where investigators wish to balance more baseline covariates than the number of groups available to study. In such situations, any model-based test adjusting for all covariates balanced by CR is expected to be invalid due to insufficient degrees of freedom. In light of this, we offer the following three comments. First, it is necessary to understand the nature of the baseline covariates for which we wish to achieve balance. Some covariates are characteristics of the group (e.g. geographical location) while some are individual-level characteristics (e.g. age and gender) aggregated at the group level. The analysis-based adjustment should use the actual individual-level characteristics to improve precision if they are collected, and the concern about degrees of freedom only comes from the number of group-level characteristics. Second, since we found that only adjustment for prognostic baseline covariates that are balanced by CR is necessary for model-based tests, we should not adjust for non-prognostic baseline group-level covariates even if they are balanced by CR. This consideration requires us to leverage subject-matter knowledge (or evidence from existing studies) to rank the importance of the group-level covariates. Finally, if it is believed that the number of prognostic group-level covariates exceed the number of groups, we may consider adjusting for the first few principal components of these covariates to avoid substantial loss in the degrees of freedom. However, we have not investigated this approach. A robust alternative is to use randomization-based inference, whose validity is unaffected even if some prognostic covariates balanced by CR are left out in the analysis (perhaps those covariates that are of poor prognostic values based on subject-matter judgment).

For the two balance metrics we evaluated, we found little evidence to favor one metric over the other, because the subsequent tests had similar size and power. This similarity is anticipated since the two balance metrics under comparison are highly correlated: for example, the Spearman rank correlations between the balance scores calculated from the two metrics are 0.965 for the R/R vaccination trial and 0.956 for the STOP CRC trial in Figure 1. Given evidence from prior studies, more informed choices of the weights (ωk and ω̃k in equations (1) and (2)) can sometimes be used to reflect the knowledge that certain covariates are more strongly related to the outcome than others, and additional research on these decisions are warranted in the presence of pilot data. Compared to the choice of a balance metric, the size of randomization space appears to be a more crucial concern. Typically, power gain is achieved with a small randomization space, but this does not suggest a monotone inverse relationship. In fact, an unreasonably small randomization space not only can risk deterministic allocations of intervention (the design becomes invalid) [12], but also may fail to support a permutation test with a fixed size [18]. In our simulations with g = 8 and g = 13, a constrained randomization space q = 0.1 works fairly well in terms of test power. For other specific applications, investigators may use the algorithm proposed by Moulton [12] to check the validity of the constrained randomization to avoid a design that is overly constrained.

In contrast to our previous results for continuous outcomes, we provided a cautionary note on the use of different model-based tests in small GRTs. We confirmed that, under SR, the mixed-model F-test based on likelihood approximation was anti-conservative with a few groups, and hence should not be used to test the intervention effect. We also compared the default denominator of degrees of freedom provided by PROC NLMIXED (equals the number of groups minus the number of variance component parameters, 2g − 1), and the results were barely changed. One reviewer suggested the use of likelihood ratio test, which in our simulations demonstrated liberal size with both g = 8 and g = 13 under both SR and CR (Web Figure 6 and 7). However, the linearization F-test had better control of type I error rate and therefore is a valid test with proper covariate adjustment even with limited groups under both randomization designs.

Similar to the previous report [36], we found the MD-corrected GEE t-test is conservative, which is due to overly inflating the robust sandwich variance estimator, while the KC-corrected GEE t-test demonstrated better control of type I error. Although the KC-corrected GEE t-test tended to be liberal under SR, it maintained the nominal type I error rate under CR provided the balanced prognostic covariates are accounted for. Although the FG-corrected sandwich estimator has been shown to perform well in simpler scenarios without additional covariates [32, 35], it gave a liberal test under SR adjusting for group-level covariates. Ford and Westgate [46] proposed using the average of KC-corrected and MD-corrected standard errors for the GEE t-test, and demonstrated better type I error rate control in their simulations under SR. However, their proposal may be slightly conservative under CR since the KC-corrected t-test consistently carries the nominal size whereas the MD-corrected t-test is conservative. Future research is needed to examine the performance of the average standard error estimator under CR.

We found that although differences occur among the linearization F-test, KC-corrected GEE t-test and the two permutation tests when the prognostic covariates are not fully adjusted in CR, all four tests had similar power after adjusting for prognostic group-level covariates. However, since the linearization F-test, KC-corrected GEE t-test and the likelihood P-test rely heavily on the specification of generalized linear (mixed) model, they are prone to power loss without proper covariate adjustment compared with the residual permutation test. For instance, constrained randomization substantially increased the power of the unadjusted residual permutation test compared to other unadjusted tests. In addition, the residual permutation test is computationally convenient and can be easily programmed in existing software. We believe the residual permutation test offers a simple and powerful alternative in testing for intervention effect in small GRTs under constrained randomization.

A possible limitation of the study is that our simulations assumed a balanced design, that is, we assume the same number of groups per arm as well as the same number of individuals per group. Design balance at the group level is common with GRTs, and is essential to ensure the validity of the permutation tests [41]. Although variations in group sizes should not affect the validity of permutation tests [41], the appropriate choice of model-based tests may depend on the degree of group size variability [35, 47]. Another possible limitation is that we only considered group-level binary covariates in generating the outcome data. The group-level binary covariates are used in the data generation for illustration purposes, and can be easily generalized to group-level continuous covariates. In other studies where individual-level covariates are available prior to randomization, constrained randomization can easily accommodate the aggregated group-level covariate means, and subsequent analysis should adjust for the prognostic individual-level covariates to gain higher precision, similar to our idea of analysis-based adjustment for group-level covariates. Third, we have limited our discussions to two representative scenarios with prognostic and non-prognostic group-level covariates, and subsequent work is needed to assess the utility of design-based and analysis-based covariate adjustment when the group-level covariates have very poor prognostic values. Diehr et al. [48] and Proschan [49] found that the unpaired t-test is equivalent to or even preferred over the paired t-test when the prognostic value of the matching variable is poor in pair-matched, small GRTs (no greater than 8 matched pairs); similarly, our unadjusted test may be justified with g = 8 when constrained randomization balances baseline covariates with poor prognostic values. Finally, we have only considered scenarios with constant ICC values for participating groups. In some cases, the intervention effect may not be constant and will likely lead to higher ICC values for groups receiving intervention [50]. However, we would still expect the permutation tests to remain valid. Future research is warranted to examine whether the linearization F-test and KC-corrected GEE t-test maintain the nominal size in small samples with heterogeneous ICC.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by the Office of The Director, National Institutes of Health, and supported by the NIH Common Fund through a cooperative agreement (U54 AT007748) with the NIH Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory. The views presented here are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank Dr. Miriam Dickinson and Dr. Gloria Coronado in the Collaboratory group for sharing the data set from the R/R immunization trial and the STOP CRC trial. We are grateful to the anonymous associate editor and referees for their helpful comments that substantially improved the paper.

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web site.

References

- 1.Murray DM. Design and Analysis of Group-Randomized Trials. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donner A, Klar N. Design and Analysis of Group-Randomized Trials in Health Research. Arnold; London: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eldridge S, Kerry S. A Practical Guide to Cluster Randomised Trials in Health Services Research. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, West Sussex: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campbell MJ, Walters SJ. How to Design, Analyse and Report Cluster Randomised Trials in Medicine and Health Related Research. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, West Sussex: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayes RJ, Moulton LH. Cluster Randomised Trials. Taylor & Francis Group, LLC; Boca Raton, FL: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eldridge SM, Ukoumunne OC, Carlin JB. The intra-cluster correlation coefficient in cluster randomized trials: a review of definitions. International Statistical Review. 2009;77(3):378–394. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murray DM, Varnell SP, Blitstein JL. Design and analysis of group-randomized trials: a review of recent methodological developments. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(3):423–432. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turner EL, Li F, Gallis JA, Prague M, Murray DM. Review of Recent Methodological Developments in Group-Randomized Trials: Part 1–Design. American Journal of Public Health. 2017;107(6):907–915. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivers NM, Halperin IJ, Barnsley J, Grimshaw JM, Shah BR, Tu K, Upshur R, Zwarenstein M. Allocation techniques for balance at baseline in cluster randomized trials: a methodological review. Trials. 2012;13(1):120–128. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Makuch RW, Brass LM, Horwitz RI. Stratified randomization for clinical trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1999;52(1):19–26. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00138-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donner A, Klar N. Pitfalls of and controversies in cluster randomization trials. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(3):416–422. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moulton LH. Covariate-based constrained randomization of group-randomized trials. Clinical Trials. 2004;1(3):297–305. doi: 10.1191/1740774504cn024oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raab GM, Butcher I. Balance in cluster randomized trials. Statistics in Medicine. 2001;20(3):351–65. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20010215)20:3<351::aid-sim797>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez AV, Steyerberg EW, Habbema JDF. Covariate adjustment in randomized controlled trials with dichotomous outcomes increases statistical power and reduces sample size requirements. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2004;57(5):454–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raab GM, Day S, Sales J. How to select covariates to include in the analysis of a clinical trial. Controlled Clinical Trials. 2000;21(4):330–342. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright N, Ivers N, Eldridge S, Taljaard M, Bremner S. A review of the use of covariates in cluster randomized trials uncovers marked discrepancies between guidance and practice. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2015;68(6):603–609. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Austin PC. A comparison of the statistical power of different methods for the analysis of cluster randomization trials with binary outcomes. Statistics in Medicine. 2007;26(19):3550–3565. doi: 10.1002/sim.2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li F, Lokhnygina Y, Murray DM, Heagerty PJ, Delong ER. An evaluation of constrained randomization for the design and analysis of group-randomized trials. Statistics in Medicine. 2015;35(10):1565–1579. doi: 10.1002/sim.6813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Hoop E, Teerenstra S, Van Gaal BGI, Moerbeek M, Borm GF. The “best balance” allocation led to optimal balance in cluster-controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2012;65(2):132–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dickinson LM, Beaty B, Fox C, Pace W, Dickinson WP, Emsermann C, Kempe A. Pragmatic cluster randomized trials using covariate constrained randomization: a method for practice-based research networks (PBRNs) Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2015;28(5):663–672. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.05.150001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coronado GD, Vollmer WM, Petrik A, Taplin SH, Burdick TE, Meenan RT, Green BB. Strategies and opportunities to STOP colon cancer in priority populations: design of a cluster-randomized pragmatic trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials. 2014;38(2):344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolfinger R, O’Connell M. Generalized linear mixed models: a pseudo-likelihood approach. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation. 1993;48(3):233–243. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinheiro J, Bates D. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS. Springer; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pinheiro J, Bates D. Approximations to the log-likelihood function in the nonlinear mixed-effects model. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 1995;4(1):12–35. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li P, Redden DT. Comparing denominator degrees of freedom approximations for the generalized linear mixed model in analyzing binary outcome in small sample cluster-randomized trials. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2015;15(1):38. doi: 10.1186/s12874-015-0026-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schluchter M, Elashoff JT. Small-sample adjustments to tests with unbalanced repeated measures assuming several covariance structures. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation. 1990;19(37):69–87. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 28.McCulloch CE, Searle SR, Neuhaus JM. Generalized, Linear, and Mixed Models. John Wiley & Sons, Inc; Hoboken, New Jersey: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wedderburn RWM. Quasi-likelihood functions, generalized linear models, and the Gauss-Newton method. Biometrika. 1974;61(3):439–447. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mancl LA, DeRouen TA. A covariance estimator for GEE with improved small-sample properties. Biometrics. 2001;57(1):126–134. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kauermann G, Carroll R. A note on the efficiency of sandwich covariance matrix estimation. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001;96(456):1387–1396. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fay MP, Graubard BI. Small-sample adjustments for Wald-type tests using sandwich estimators. Biometrics. 2001;57(4):1198–1206. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.01198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pan W, Wall MM. Small-sample adjustments in using the sandwich variance estimator in generalized estimating equations. Statistics in Medicine. 2002;21(10):1429–1441. doi: 10.1002/sim.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morel JG, Bokossa MC, Neerchal NK. Small sample correction for the variance of GEE estimators. Biometrical Journal. 2003;45(4):395–409. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li P, Redden DT. Small sample performance of bias-corrected sandwich estimators for cluster-randomized trials with binary outcomes. Statistics in Medicine. 2015;34(2):281–296. doi: 10.1002/sim.6344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lu B, Preisser JS, Qaqish BF, Suchindran C, Bangdiwala SI, Wolfson M. A comparison of two bias-corrected covariance estimators for generalized estimating equations. Biometrics. 2007;63(3):935–941. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2007.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Westgate PM. On small-sample inference in group randomized trials with binary outcomes and cluster-level covariates. Biometrical Journal. 2013;55(5):789–806. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201200237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fisher R. The Design of Experiments. Oliver and Boyd; Edinburgh: 1935. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Good P. Permutation Tests. A Pratical Guide to Resampling Methods for Testing Hypotheses. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Edgington E. Randomization Tests. Marcel-Decker; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gail MH, Mark SD, Carroll RJ, Green SB, Pee D. On design considerations and randomization-based inference for community intervention trials. Statistics in Medicine. 1996;15(11):1069–92. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960615)15:11<1069::AID-SIM220>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braun TM, Feng Z. Optimal permutation tests for the analysis of group randomized trials. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001;96(456):1424–1432. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murray DM, Hannan PJ, Pals SP, McCowen RG, Baker WL, Blitstein JL. A comparison of permutation and mixed-model regression methods for the analysis of simulated data in the context of a group-randomized trial. Statistics in Medicine. 2006;25(3):375–88. doi: 10.1002/sim.2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Murray DM, Blitstein JL. Methods to reduce the impact of intraclass correlation in group-randomized trials. Evaluation Review. 2003 Feb;27(1):79–103. doi: 10.1177/0193841X02239019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Q, Pierce DA. A note on Gauss-Hermite quadrature. Biometrika. 1994;81(3):624–629. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ford WP, Westgate PM. Improved standard error estimator for maintaining the validity of inference in cluster randomized trials with a small number of clusters. Biometrical Journal. 2017;59(3):478–495. doi: 10.1002/bimj.201600182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turner EL, Prague M, Gallis JA, Li F, Murray DM. Review of Recent Methodological Developments in Group-Randomized Trials: Part 2–Analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2017;107(7):1078–1086. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Diehr P, Martin DC, Koepsell T, Cheadle A. Breaking the matches in a paired t-test for community interventions when the number of pairs is small. Statistics in Medicine. 1995;14(13):1491–1504. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780141309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Proschan MA. On the distribution of the unpaired t-statistic with paired data. Statistics in Medicine. 1996;15(10):1059–1063. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960530)15:10<1059::AID-SIM219>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Omar RZ, Thompson SG. Analysis of a cluster randomized trial with binary outcome data using a multi-level model. Statistics in medicine. 2000 Oct;19(19):2675–88. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001015)19:19<2675::aid-sim556>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.