Abstract

The chloroquine resistance transporter of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, PfCRT, is an important determinant of resistance to several quinoline and quinoline-like antimalarial drugs. PfCRT also plays an essential role in the physiology of the parasite during development inside erythrocytes. However, the function of this transporter besides its role in drug resistance is still unclear. Using electrophysiological and flux experiments conducted on PfCRT-expressing Xenopus laevis oocytes, we show here that both wild-type PfCRT and a PfCRT variant associated with chloroquine resistance transport both ferrous and ferric iron, albeit with different kinetics. In particular, we found that the ability to transport ferrous iron is reduced by the specific polymorphisms acquired by the PfCRT variant as a result of chloroquine selection. We further show that iron and chloroquine transport via PfCRT is electrogenic. If these findings in the Xenopus model extend to P. falciparum in vivo, our data suggest that PfCRT might play a role in iron homeostasis, which is essential for the parasite's development in erythrocytes.

Keywords: drug transport, iron, kinetics, malaria, plasmodium, Xenopus, PfCRT

Introduction

The chloroquine resistance transporter (PfCRT)4 plays a pivotal role in the physiology and pathophysiology of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. PfCRT is an essential factor during intraerythrocytic development of the parasite, and it is a determinant of resistance to antimalarial drugs (1–3). PfCRT resides at the membrane of the parasite's digestive vacuole (1), a proteolytic organelle involved in hemoglobin degradation and a target for antimalarial drugs. Diverse PfCRT variants have emerged under drug selection in different parts of the world and are associated with altered susceptibility of the parasite to a wide range of quinoline and quinoline-like antimalarial drugs, including the former first line drug chloroquine and the currently used antimalarials amodiaquine, quinine, and lumefantrine (2–4).

PfCRT confers altered drug phenotypes by acting as an efflux carrier (5–8), expelling compounds from the digestive vacuole, where these drugs are thought to interfere with endogenous heme detoxification pathways. The transport of drugs seems to occur in association with protons and to be dependent on the membrane potential, suggesting a model of PfCRT as a proton-coupled and potential-driven facilitating carrier (9–11). The drug-transporting function of PfCRT is dependent on an amino acid substitution of threonine for lysine at position 76 that is conserved among geographic PfCRT variants (12, 13). The replacement of a positively charged amino acid with an uncharged residue is thought to allow positively charged drugs, such as chloroquine, to enter the binding pocket. In total, geographic PfCRT variants harbor between 4 and 10 mutations (2). The additional mutational changes augment the drug-transporting activity and/or balance it with fitness costs (13, 14).

In contrast to our deepening understanding of the role of PfCRT in drug resistance, the physiological function of PfCRT has remained largely enigmatic. Sequence analyses and homology searches have grouped PfCRT among the drug/metabolite carrier superfamily based on the protein topology, with a predicted number of 10 transmembrane domains and an internal 2-fold pseudosymmetry (15, 16). However, robust in silico predictions on the physiological function of PfCRT have been hampered by a paucity of closely related homologs with annotated function in other species. An early report suggesting that PfCRT resembles bacterial voltage-gated chloride channels could not be confirmed (17). Maughan et al. (18) reported a resemblance of PfCRT with a family of thiol transporters in Arabidopsis thaliana, termed PfCRT-like transporters (CLTs) that export glutathione and its precursor γ-glutamylcysteine from the chloroplast where γ-glutamylcysteine is exclusively made. On the basis of this finding, and taking into account that mutations in both CLTs and PfCRT affect glutathione homoeostasis in A. thaliana and P. falciparum, a function of PfCRT in glutathione transport was proposed (18–20). Other studies have implicated PfCRT in polyspecific cation transport and, in addition to glutathione, proposed also choline; tetraethyl ammonium (TEA); the amino acids histidine, lysine, and arginine; and the polyamines spermine and spermidine as putative substrates (21). However, these studies have remained controversial mainly because none of these organic cations were able to compete with chloroquine for transport via PfCRT in a functional heterologous expression system, based on oocytes from the South African clawed toad Xenopus laevis, which display PfCRT at their plasma membrane (5).

Here we have investigated the physiological function of PfCRT expressed in X. laevis oocytes. Our data suggest that both wild-type PfCRT and a PfCRT variant associated with chloroquine resistance confer electrogenic iron transport. PfCRT does not discriminate absolutely between ferric and ferrous iron, setting PfCRT apart from the mammalian divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) and other known iron-transporting systems (22, 23). However, the PfCRT variant associated with chloroquine resistance displayed kinetic parameters with regard to ferrous iron that were distinct from those of the wild type.

Results

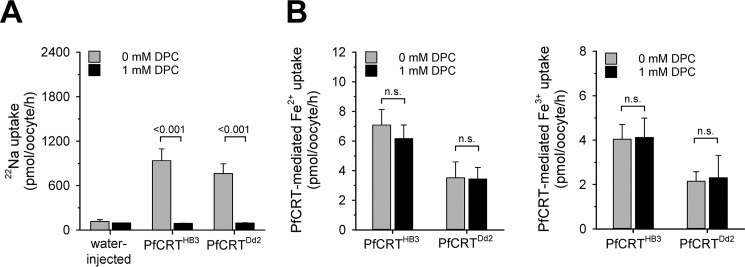

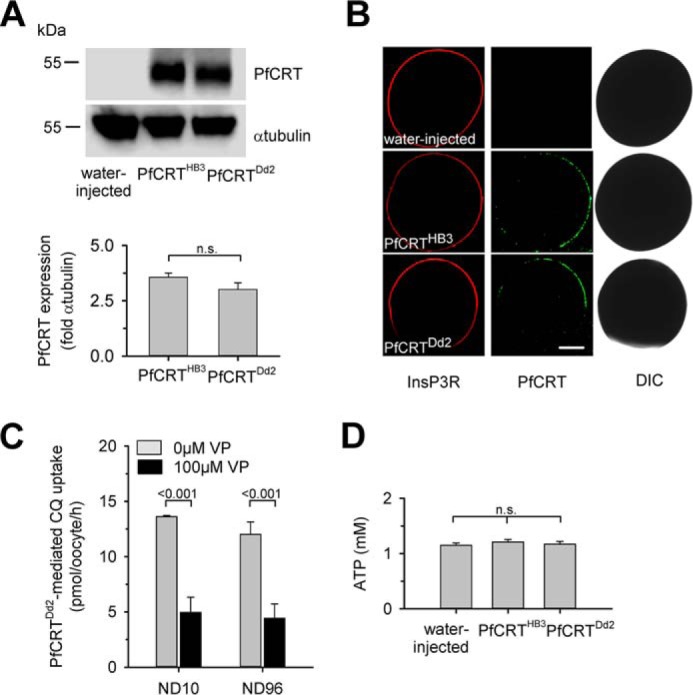

PfCRT is an electrogenic carrier of chloroquine

To study the transport function of PfCRT, we expressed the wild-type form of the protein from the chloroquine-sensitive strain HB3 and the polymorphic variant from the chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum strain Dd2 in X. laevis oocytes. The PfCRT variant from the Dd2 strain differs from the wild-type protein in 8 amino acid substitutions, including the conserved K76T mutation. Expression was verified by Western analyses and immunofluorescence assays, using a guinea pig antiserum specific to PfCRT (Fig. 1, A and B). Western blot analysis identified a protein with the expected molecular mass of PfCRT of 48.6 kDa, and immunofluorescence images revealed co-localization of PfCRT with the oolemma marker inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor (24) in both PfCRTHB3- and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes (Fig. 1, A and B). Water-injected oocytes did not react with the PfCRT-specific antiserum (Fig. 1, A and B). Quantification of the specific signals in the Western analysis suggests comparable expression levels of both PfCRT variants, relative to the internal α-tubulin standard (Fig. 1A), consistent with previous reports (13).

Figure 1.

Expression of PfCRT in X. laevis oocytes. A, Western blot analysis of total lysates from oocytes injected with water, PfCRTHB3 cRNA, and PfCRTDd2 cRNA, using a polyclonal guinea pig antiserum specific to PfCRT and a polyclonal rabbit antiserum specific to α-tubulin. A size standard is indicated in kilodaltons. The hybridization signals were subsequently quantified, yielding the expression levels of PfCRTHB3 and PfCRTDd2 relative to the internal standard α-tubulin. The means ± S.E. (error bars) from the number of independent biological replicates NBR = 4 independent Western blot analyses are shown. B, confocal fluorescence images of fixed PfCRTDd2 and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes and water-injected control oocytes. Left, fluorescence image of InsP3R, using a specific rabbit antisera and an Alexa Fluor 546 anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Middle, fluorescence image of PfCRT, using a specific guinea pig antiserum and the Alexa Fluor 488 anti-guinea pig secondary antibody. Right, differential interference contrast image. Bar, 250 μm. C, effect of ND10 and ND96 buffer, pH 5.5, on PfCRTDd2-mediated chloroquine uptake in the presence and absence of verapamil (VP; 100 μm). Oocytes were incubated in the respective buffer, pH 7.5, from the moment of cRNA injection. For the flux experiments, chloroquine was added at a final concentration of 50 μm unlabeled chloroquine and 42 nm [3H]chloroquine, and the amount of uptake was determined after 60 min of incubation. The means ± S.E. of NBR = 4 independent biological determinations are shown. Statistical significance was assessed using the two-tailed t test. D, intracellular ATP levels of water-injected oocytes and oocytes expressing PfCRTHB3 or PfCRTDd2. Oocytes were incubated in ND10 buffer, pH 7.5, after cRNA injection, for 3 days before the intracellular ATP levels were determined. The mean ± S.E. of NBR = 5 independent biological determinations are shown. The statistical significance was assessed using the Holm–Sidak one-way ANOVA test or a two-tailed t test, where appropriate. n.s., not significant.

Several studies have suggested that drug transport via PfCRT is associated with protons (10, 11, 25). To explore the possibility of an electrogenic transport process, we studied the electrophysiological effect of chloroquine on PfCRTHB3- and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes, using the two-electrode voltage clamp technique. Water-injected oocytes were analyzed in parallel. Oocytes were kept in a low-Na+-containing buffer, pH 7.5 (10 mm NaCl and 86 mm NMDG chloride, henceforth termed ND10 buffer) from the moment of RNA injection to reduce the impact of the non-selective cationic conductance activated in PfCRT-expressing oocytes on electrophysiological parameters (26). The activation of the non-selective cationic conductance would lead to a low membrane potential and an elevated intracellular free Na+ concentration (supplemental Table S1) (26). Prior to the electrophysiological experiments, oocytes were pre-equilibrated for 30 min in ND10 buffer, pH 6.0. This protocol fully maintained verapamil-sensitive chloroquine transport activity in PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes, as verified in flux experiments, using radiolabeled chloroquine and by comparing the amount of chloroquine taken up by oocytes kept in ND10 or ND96 buffer (Fig. 1C). Moreover, oocytes incubated in ND10 buffer had intracellular ATP levels in the normal range of 1–2 mm (27, 28) (Fig. 1D). These findings demonstrate that the oocytes incubated in ND10 buffer are viable and healthy, consistent with previous reports (29–31).

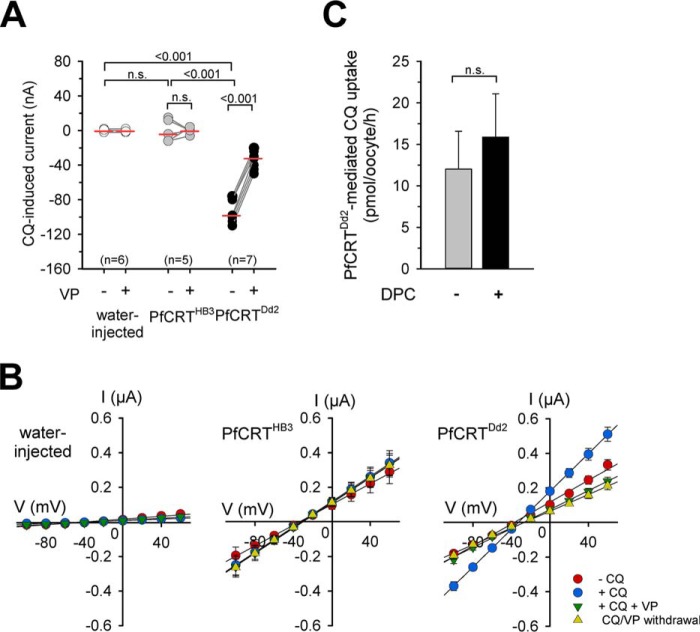

Chloroquine (100 μm) induced an inward current in oocytes expressing PfCRTDd2 clamped at a membrane potential (Vc) of −50 mV (p < 0.001 compared with water-injected oocytes, according to Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks test), and not in PfCRTHB3 expressing oocytes or in water-injected oocytes (Fig. 2A and supplemental Fig. S1A). The chosen chloroquine concentration of 100 μm corresponds to approximately half the reported Michaelis-Menten constant Km of chloroquine for PfCRTDd2 of 245 μm, as determined in the oocyte system (5, 6, 13). The chloroquine-induced currents were sensitive to verapamil (100 μm), as demonstrated in paired experiments (Fig. 2A and supplemental Fig. S1A; p < 0.001, according to a paired t test). Verapamil is an established full mixed-type inhibitor of PfCRT and a chemosensitizer of chloroquine resistance in vitro (6, 32). The finding that chloroquine induced an inward current in PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes and not in PfCRTHB3-expressing oocytes or in water-injected controls was further supported by current–voltage relationships, showing a chloroquine-induced increase in basal membrane conductance Gm (Fig. 2B). The increase in basal membrane conductance was maintained in the presence of diphenylamine 2-carboxylic acid (DPC; 1 mm), an established inhibitor of the endogenous non-selective cation conductance (33, 34) (supplemental Fig. S2). These findings, together with the observation that chloroquine uptake by PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes was independent of DPC (1 mm) (Fig. 2C), exclude the possibility that the chloroquine-induced currents are related to or conferred by the endogenous non-selective cation conductance activated by the heterologous expression of PfCRT. Instead, our findings are consistent with electrogenic transport of chloroquine via PfCRTDd2.

Figure 2.

Chloroquine-induced currents in PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes. A, water-injected oocytes (white circles), PfCRTHB3-expressing oocytes (gray circles), and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes (black circles) were voltage-clamped (−50 mV) while superfused with ND10 buffer, pH 6.0. The currents induced upon the addition of 100 μm chloroquine (CQ) were measured before and after supplementation of the medium with 100 μm VP in paired experiments. The lines connecting two data points indicate the response of a single oocyte before and after the treatment. The number of oocytes (n) investigated is indicated above the x axis. The medians are indicated as red lines. The statistical significance was assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks test or the paired t test, where appropriate. The corresponding p values are indicated on the graphs. n.s., not significant. B, current–voltage relationships of water-injected oocytes (left), PfCRTHB3-expressing oocytes (middle), and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes (right) were first obtained in ND10 buffer (red-filled circles) and then ND10 buffer containing 100 μm chloroquine (blue-filled circles) before adding 100 μm VP (green-filled inverted triangles). I/V curves upon withdrawal of both compounds are indicated by yellow-filled triangles. Each data point represents the mean ± S.E. (error bars) from n = 15 oocytes. C, PfCRTDd2-mediated chloroquine uptake in the presence and absence of 1 mm DPC. PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes and water-injected oocytes were incubated in ND96 buffer supplemented with and without 1 mm DPC and containing 42 nm [3H]chloroquine and 50 μm unlabeled chloroquine for 60 min at 25 °C. To calculate the amount of PfCRTDd2-mediated transport, the amount of chloroquine taken up by water-injected oocytes was subtracted. The data represent the means ± S.E. of NBR = 4 independent biological determinations. n.s., not significant according to a t test.

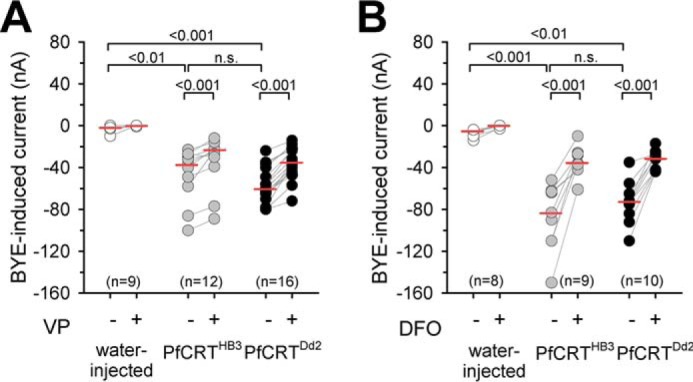

Iron-induced currents in PfCRT-expressing oocytes

The electrogenic nature of drug transport via PfCRT offered the opportunity to screen for putative substrates using a previously established generic approach based on exposing oocytes to a complex mixture of metabolites as is present in bacto-yeast extract (BYE) and recording substrate-induced electric signals in a two-electrode voltage-clamped set up (35). Application of BYE (0.5% in ND10 buffer, pH 6.0) immediately induced a significant inward current in clamped (Vc = −50 mV) PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes, comparable with the currents induced by chloroquine (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. S1B; p < 0.001, according to Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks test). Interestingly, BYE also induced a negative current in PfCRTHB3 expressing oocytes, which was statistically not different from the BYE-induced currents observed in PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes (according to Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks test) (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. S1B). The BYE-induced currents were partly but significantly prevented by verapamil in both PfCRTDd2- and PfCRTHB3-expressing oocytes (p < 0.001, according to a paired t test, for both PfCRTDd2 and PfCRTHB3), as shown in paired experiments (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. S1B). BYE did not induce major currents in water-injected oocytes (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. S1B), consistent with previous reports (35). These findings are consistent with an electrogenic transport process, with both the wild-type and the mutated PfCRT interacting with at least one component present in BYE.

Figure 3.

BYE-induced inward currents in PfCRT-expressing X. laevis oocytes. A and B, water-injected oocytes (white circles), PfCRTHB3-expressing oocytes (gray circles), and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes (black circles) were voltage-clamped (−50 mV) while superfused with ND10 buffer, pH 6.0. The currents induced upon the addition of 0.5% BYE were measured before and after supplementation of the medium with 100 μm VP (A) or 100 μm DFO (B) in paired experiments. The number of oocytes investigated is indicated above the x axis. The medians are indicated as red lines. The statistical significance was assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks test or paired t test, where appropriate. The corresponding p values are indicated on the graphs. n.s., not significant.

Given that BYE contains several of the proposed substrates of PfCRT, including positively charged amino acids, thiols, polyamines, and oligopeptides, we tested whether one or several of them induced an inward current. However, neither arginine, lysine, histidine, nor glutathione was active in our system at a concentration of 1 mm (supplemental Fig. S3A). We further observed no responses with choline, TEA (a characteristic substrate of organic cation transporters), or glycylsarcosine (a surrogate substrate for mammalian oligopeptide carriers) at a concentration of 2 mm (supplemental Fig. S3A). We validated these negative results for each of these putative substrates in flux assays, using radiolabeled compounds at a concentration close to and ∼10-fold below the previously reported Km of these organic biomolecules for PfCRT (21). None were taken up by PfCRT-expressing oocytes (supplemental Fig. S3, A and B). We further tested the negatively charged amino acids glutamic acid and aspartic acid and the apolar amino acids leucine and proline. Again, no electrical signals and no uptake were observed (supplemental Fig. S3, A and B). Furthermore, we found no evidence for facilitated uptake of the polyamines putrescine or spermine by PfCRT-expressing oocytes (supplemental Fig. S3, A and B).

Considering that the digestive vacuole is the site of hemoglobin degradation and that the physiological function of PfCRT might directly or indirectly relate to this biological process, we inspected the list of BYE ingredients for other products of hemoglobin degradation that might be transported by PfCRT. An obvious candidate is iron, of which BYE contains 55.3 μg g−1 dry weight (36). To test whether the PfCRT-associated currents are induced by iron, we compared, in paired experiments, the effect of BYE and BYE supplemented with the iron-chelating agent deferoxamine (DFO; 100 μm) on the amplitude of the currents. DFO significantly prevented the BYE-induced inward currents in both PfCRTHB3- and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes (p < 0.001, according to a paired t test) (Fig. 3B and supplemental Fig. S1C).

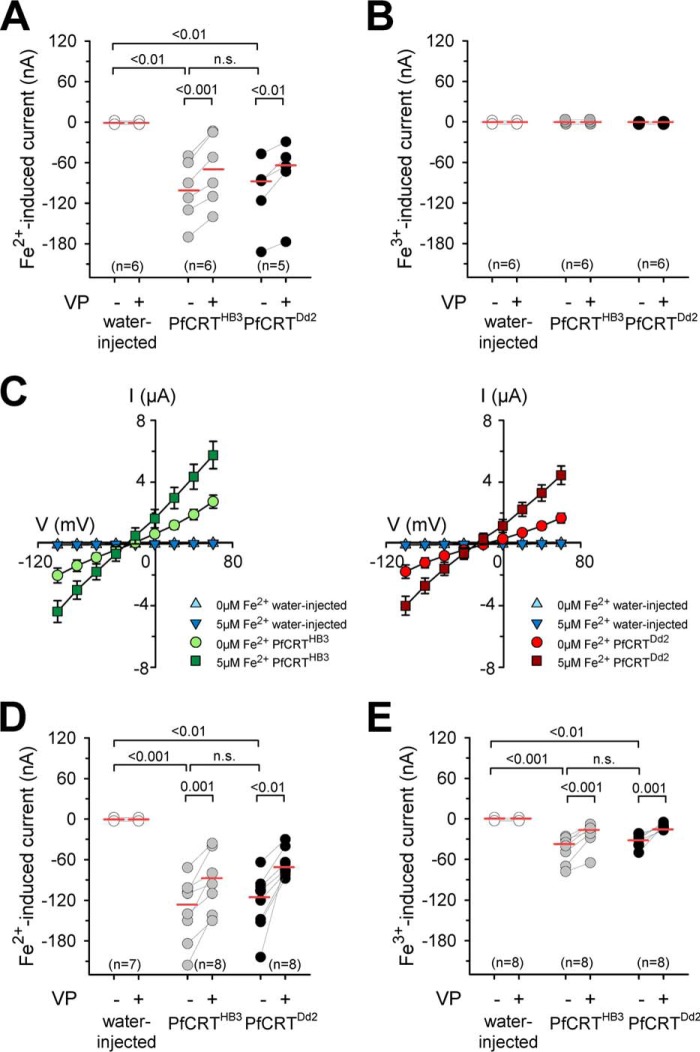

The suggestion of the currents being iron-inducible was subsequently verified by superfusing the oocytes with BYE-free ND10 buffer containing iron at a concentration of 5 μm, which corresponds to the amount of iron present in a 0.5% BYE solution. To distinguish between effects brought about by ferrous (Fe2+) and ferric iron (Fe3+), an ND10 buffer system was used that was supplemented with ascorbic acid or nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) to maintain iron in its reduced Fe2+ or its oxidized Fe3+ state, respectively (22). The addition of 5 μm iron induced, in voltage-clamped cells (Vc = −50 mV), an inward current in both PfCRTHB3- and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes (p < 0.01 compared with water-injected oocytes, according to Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks test), but only in the case of Fe2+ and not Fe3+ (Fig. 4, A and B). Current–voltage relationships confirmed the Gm increase in the presence of ferrous iron in PfCRT-expressing oocytes (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Iron-induced inward currents in PfCRT-expressing X. laevis oocytes. A and B, water-injected oocytes (white circles), PfCRTHB3-expressing oocytes (gray circles), and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes (black circles) were voltage-clamped (−50 mV) while superfused with ND10 buffer, pH 6.0. Iron was maintained in divalent form or trivalent form by adding to the buffer a quadruple ratio of l-ascorbic acid or nitrilotriacetic acid, respectively. The currents induced by adding 5 μm Fe2+ (A) or 5 μm Fe3+ (B) were measured before and after supplementation of the medium with 100 μm VP. The number (n) of oocytes is indicated above the x axis. The medians are indicated as red lines. The statistical significance was assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks test or paired t test, where appropriate. The corresponding p values are indicated on the graphs. C, current–voltage relationships of water-injected oocytes and PfCRTHB3-expressing oocytes (left) and water-injected oocytes and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes (right) were obtained in ND10 buffer, pH 6.0, in the presence and absence of 5 μm ferrous iron. Each data point represents the mean ± S.E. (error bars) of n = 12–15 oocytes. D and E, as in A and B, but this time, a concentration of 1 mm ferrous (D) or ferric (E) iron in ND10-mannitol buffer, pH 6.0, was used. n.s., not significant.

At an iron concentration of 1 mm, PfCRT-associated currents were also observed for ferric iron in voltage-clamped cells (Vc = −50 mV), although to a lesser extent relative to the Fe2+-induced currents at the same concentration (Fig. 4, D and E, and supplemental Fig. S4). Importantly, in all cases, the ferrous and ferric iron-induced currents could be partly inhibited by verapamil (100 μm) (p < 0.01, according to paired t tests; Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S4). Water-injected oocytes did not respond to the addition of ferrous or ferric iron (Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S4), consistent with previous reports (22). To exclude the possibility that the currents were carried by potassium, magnesium, calcium, or NMDG, the respective salts were replaced in the ND10 buffer by an equal osmotic concentration of mannitol in the physiological experiments using 1 mm iron.

Evidence of iron transport via PfCRT

We next investigated the interaction of PfCRT with ferrous and ferric iron in flux assays, using radiolabeled 55Fe. The uptake of iron by PfCRT-expressing and water-injected oocytes was measured in an acidic ND96 buffer (pH 5.5) containing 96 mm NaCl and either ascorbic acid or NTA. The buffers were validated using oocytes expressing rat DMT1, which exclusively transports ferrous and not ferric iron (supplemental Fig. S5) (22).

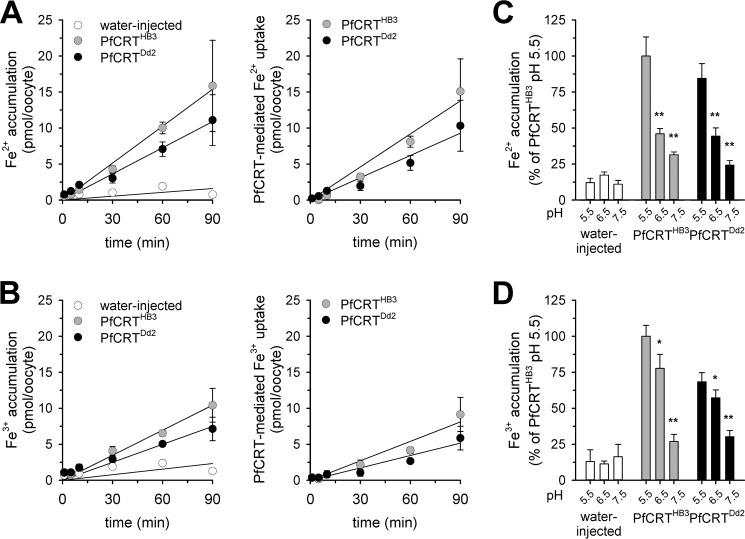

Oocytes expressing PfCRTHB3 and PfCRTDd2 took up significantly more iron from the external medium containing 2 μm radioactive 55Fe and 48 μm non-radioactive 54Fe, both in its Fe2+ and Fe3+ form, than did water-injected oocytes (p < 0.05, compared with water-injected oocytes, according to Holm–Sidak one-way ANOVA test) (Fig. 5, A and B, left panels). The specific PfCRT-attributable portion of ferrous and ferric iron uptake increased in a linear fashion with time for at least the first 90 min (Fig. 5, A and B, right panels). Ferrous and ferric iron uptake by PfCRT-expressing oocytes was pH-dependent and increased as the pH became more acidic (Fig. 5, C and D).

Figure 5.

Uptake of ferrous and ferric iron by PfCRT-expressing oocytes. A and B, time courses of ferrous (A) and ferric (B) iron uptake by water-injected oocytes (white circles), PfCRTHB3-expressing oocytes (gray circles), and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes (black circles). The uptake assays were performed using the appropriate ND96 buffer, pH 5.5, supplemented with 2 μm radiolabeled 55Fe and 48 μm unlabeled iron. A linear regression was fitted to the data points (R2 > 0.9). The right panels show the time courses of PfCRTDd2- and PfCRTHB3-mediated uptake of ferrous and ferric iron after subtracting the uptake in water-injected oocytes from that measured in PfCRTDd2- and PfCRTHB3-expressing oocytes. C and D, pH dependence of ferrous (C) and ferric (D) iron uptake. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01 according to Holm–Sidak one-way ANOVA test. Data were normalized to the amount of iron taken up by PfCRT-expressing oocytes at pH 5.5. The means ± S.E. (error bars) of NBR = 4 independent biological determinations are shown.

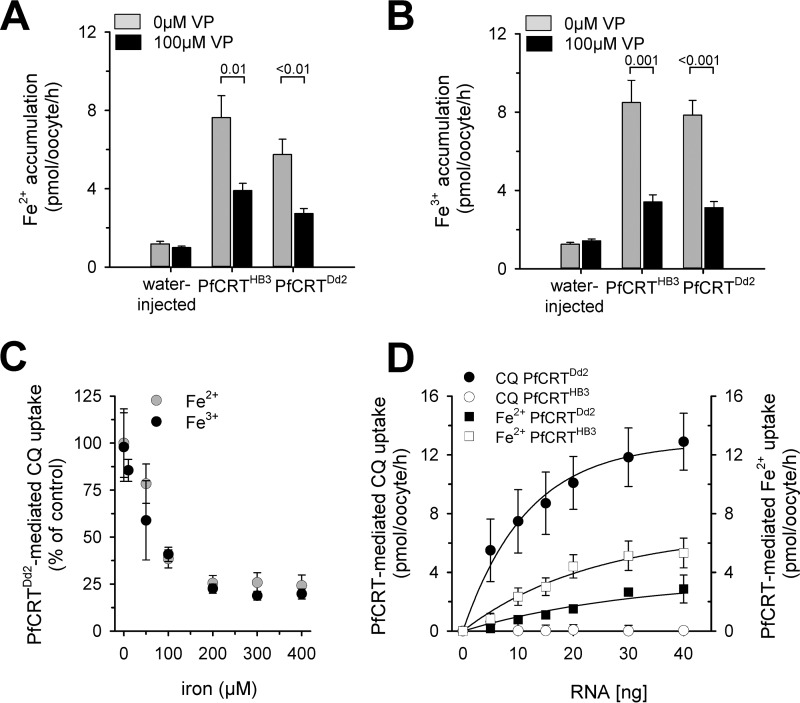

Verapamil (100 μm) inhibited the uptake of ferrous and ferric iron by PfCRT-expressing oocytes by ∼50–60% (Fig. 6, A and B). Furthermore, both iron species were able to block PfCRTDd2-mediated chloroquine uptake (Fig. 6C). The extent of iron taken up by PfCRT-expressing oocytes increased in a hyperbolic manner with the amount of PfCRT-encoding cRNA injected, as exemplified for ferrous iron (Fig. 6D). Uptake of chloroquine was measured in parallel assays using the ferrous and specific buffer (Fig. 6D), and the data obtained were consistent with previous findings (5, 13).

Figure 6.

Inhibition of PfCRT-mediated fluxes and cRNA dependence. A and B, effect of verapamil (100 μm) on the uptake of ferrous (A) or ferric (B) iron from an external concentration of 50 μm by water-injected oocytes and PfCRTHB3- and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes. Oocytes were analyzed after 60 min of incubation in the respective uptake buffer. The means ± S.E. of NBR = 7–10 independent biological determinations are shown. Statistical significance was evaluated using the two-tailed t test, and the p values are indicated on the graph. C, effect of increasing concentrations of ferrous iron (gray circle) or ferric iron (black circle) on PfCRTDd2-mediated chloroquine uptake. Data were normalized to the amount of PfCRT-mediated chloroquine uptake in the absence of iron. The means ± S.E. of NBR = 3–5 independent biological determinations are shown. D, effect of increasing amounts of cRNA injected on the amount of PfCRT-mediated chloroquine and ferrous iron uptake. Chloroquine and ferrous iron uptake (at the 60-min time point) were measured in parallel assays. The means ± S.E. (error bars) of NBR = 3 independent biological determinations are shown.

Both ferrous and ferric iron are known to create reactive oxygen radicals via the Fenton reaction. Such reactive oxygen radicals can initiate lipid peroxidation, resulting in membrane damage (37). To assess whether the presence of iron during the course of an uptake experiment adversely affected the membrane integrity of the oocytes, we preincubated PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes in the appropriate buffer containing increasing concentrations of ferrous or ferric iron, ranging from 0 to 400 μm. After 60 min of incubation, oocytes were washed and placed in ND96 buffer containing 42 nm tritiated and 50 μm unlabeled chloroquine for 60 min. No differences in chloroquine uptake were noted between iron-pretreated and untreated oocytes (supplemental Fig. S6), suggesting that pretreatment with iron, even at a dose of 400 μm for 1 h, did not affect membrane integrity or the activity of PfCRTDd2.

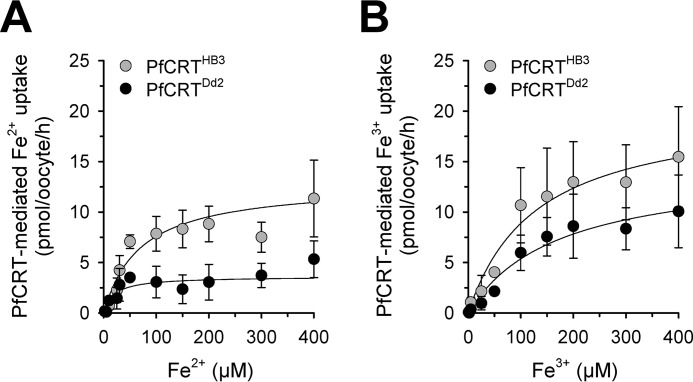

We further considered the possibility of iron uptake occurring via the non-selective cation conductance that is activated in PfCRT-expressing oocytes (26). As a result of the activated non-selective cation conductance, PfCRT-expressing oocytes revealed an enhanced Na+ influx when incubated in ND96 buffer, relative to water-injected oocytes, as determined using 22Na (Fig. 7A). The addition of DPC (1 mm) blocked 22Na influx via the non-selective cation conductance (Fig. 7A), consistent with previous reports (26). In comparison, DPC did not affect uptake of ferrous or ferric iron by PfCRT-expressing oocytes (Fig. 7B), suggesting an uptake mechanism independent of the non-selective cation conductance.

Figure 7.

Effect of DPC on Na+, Fe2+, and Fe3+ uptake by PfCRT-expressing oocytes. A, uptake of sodium ions from an external concentration of 22 μm 22Na and 5 mm unlabeled Na+ by water-injected oocytes and oocytes expressing PfCRTHB3 or PfCRTDd2 in the presence (black bar) and absence (gray bar) of DPC (1 mm). The means ± S.E. (error bars) are shown of NBR = 3 independent determinations. Statistical significance was assessed using the two-tailed t test. B, PfCRT-mediated Fe2+ (middle) and Fe3+ (right) by PfCRTHB3- and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes in the presence (black bar) and absence (gray bar) of DPC (1 mm). Results are presented as means ± S.E. of NBR = 4 independent determinations. n.s., not significant.

To investigate whether uptake of iron by PfCRT-expressing oocytes displays saturation kinetics, we incubated water-injected and PfCRT-expressing oocytes with a constant amount of radioactive 55Fe (2 μm) and different concentrations of non-radioactive 54Fe, ranging from 0 to 400 μm for 60 min before the amount of internalized radiolabel was determined. As seen in Fig. 8 (A and B), the amount of ferrous and ferric iron taken up by PfCRT-expressing oocytes approached a plateau as the total iron concentration increased, consistent with a saturable transport mechanism. Fitting the Michaelis–Menten equation to the kinetic data yielded estimates of the apparent Michaelis–Menten constant Km and the maximal transport velocity Vmax. Interestingly, the kinetic parameters for ferrous iron significantly differed between PfCRTHB3- and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes (p < 0.001 and p = 0.02 for Vmax and Km values, respectively, according to a two-tailed t test) (Table 1). PfCRTDd2 had approximately 3 times lower Km and Vmax values relative to PfCRTHB3 (Km = 20 ± 9 μm (number of independent biological replicates NBR = 5) and 70 ± 17 μm (NBR = 5), and Vmax = 4 ± 0.5 pmol oocyte−1 h−1 (NBR = 5) and 13 ± 1 pmol oocyte−1 h−1 (NBR = 5), respectively). In contrast, the kinetic parameters for ferric iron were not significantly different between the two PfCRT variants (Km = 170 ± 50 μm (NBR = 5) and 130 ± 40 μm (NBR = 5), and Vmax = 14 ± 2 pmol oocyte−1 h−1 (NBR = 5) and 20 ± 2 pmol oocyte−1 h−1 (NBR = 5), respectively; p = 0.5 and p = 0.05, respectively; according to two-tailed t-tests).

Figure 8.

Kinetics of iron uptake by PfCRT-expressing oocytes. A and B, kinetics of PfCRTDd2-mediated (black circles) and PfCRTHB3-mediated uptake (gray circles) of Fe2+ (A) and Fe3+ (B). The uptake of radiolabeled iron into water-injected oocytes and oocytes expressing PfCRTDd2 or PfCRTHB3 was measured in the appropriate ND96 buffer, pH 5.5, containing an extracellular concentration range of 2–400 μm iron (2 μm radiolabeled 55Fe and the appropriate amount of non-radioactive iron). The amount of PfCRT-mediated iron uptake was calculated by subtracting the amount measured in water-injected oocytes from that in oocytes expressing PfCRT at each iron concentration. A least-squares fit of the Michaelis-Menten equation to the resulting data yielded the kinetic parameters compiled in Table 1. The data represent the means ± S.E. (error bars) of NBR = 5 independent biological determinations, with n = 12–30 oocytes per treatment and biological replicate.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters describing the interactions of PfCRTDd2 and PfCRTHB3 with ferrous and ferric iron

Best-fit values of kinetic parameters were obtained from the kinetics of ferrous and ferric iron uptake using the Michaelis–Menten equation (Fig. 8). The means ± S.E. of NBR (shown in parentheses) independent biological determinations are shown. Statistical significance was determined between corresponding kinetic parameters, using a two-tailed t test.

| Iron | Parameters | PfCRTHB3 | PfCRTDd2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe2+ | Apparent Vmax (pmol oocyte−1 h−1) | 13 ± 1 (5) | 4 ± 0.5 (5) | <0.001 |

| Apparent Km (μm) | 70 ± 17 (5) | 20 ± 9 (5) | 0.02 | |

| Fe3+ | Apparent Vmax (pmol oocyte−1 h−1) | 20 ± 2 (5) | 14 ± 2 (5) | 0.05 |

| Apparent Km (μm) | 130 ± 40 (5) | 170 ± 50 (5) | 0.5 |

When assessing the substrate specificity of each PfCRT variant, it is apparent that PfCRTHB3 displayed comparable Km values for both ferrous and ferric iron (p = 0.2, according to a two-tailed t test) but significantly different Vmax values (p < 0.01, according to a two-tailed t test) (Table 1). In comparison, PfCRTDd2 revealed both significantly different Km and Vmax values with regard to ferrous and ferric iron (p = 0.02 and p < 0.001, respectively, according to a two-tailed t test) (Table 1). Thus, the mutations that distinguish PfCRTDd2 from PfCRTHB3 and bring about the drug-transporting function affect the carrier's handling of ferrous iron, whereas the ferric iron transport seems to be largely unaffected by these mutational changes.

Discussion

Our data show that both the wild-type and a PfCRT variant associated with chloroquine resistance are able to transport ferrous and ferric iron when functionally expressed in X. laevis oocytes. This finding is supported by both electrophysiological and flux studies.

To identify putative substrates of PfCRT, we employed a recently established generic approach based on exposing oocytes expressing a transporter of unknown functionality to the complex metabolite mixture of a diluted bacto-yeast extract solution and recording substrate-induced electric signals in a two-electrode voltage-clamped setup (35). This approach, as elegant as it is, has one precondition; the transport process must be electrogenic to record an electrical signal. Although previous studies have proposed that PfCRT transports chloroquine together with protons (10, 11), the electrogenic nature of this transport process has yet to be formally demonstrated. To record such electrical currents, we had to suppress endogenous conductances activated by the expression of PfCRT (26) (supplemental Table S1). Activation of endogenous conductances is regularly observed in oocytes expressing heterologous proteins (38–41).

With the activity of the non-selective cation conductance reduced and intracellular Na+ overload prevented, we were able to show that the addition of chloroquine elicited a measureable inward rectifying current in voltage-clamped PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes, and not in PfCRTHB3-expressing oocytes or water-injected oocytes. We excluded the possibility that these chloroquine-induced currents are related to the activated non-selective cation conductance, on the basis of a lack of responsiveness to the inhibitor DPC (supplemental Fig. S2). In contrast, the chloroquine-induced currents were significantly blocked by the addition of verapamil, the well-studied full mixed type inhibitor of chloroquine transport on PfCRTDd2 (Fig. 2A) (6). Thus, our findings causatively link the electrical signals elicited by chloroquine to the activity of PfCRT and support a model of PfCRTDd2 acting as an electrogenic transporter of chloroquine. We explain the negative chloroquine-induced currents by the influx of net positive charges into the oocyte, which is consistent with PfCRT-mediated chloroquine transport in association with H+ in the parasite (10, 11).

Establishing the electrogenic transport activity of PfCRTDd2 enabled a global screen for physiological substrates, based on diluted BYE and the recording of BYE-induced electrical signals. Indeed, BYE induced measurable signals of a verapamil-sensitive inward current in both PfCRTDd2- and PfCRTHB3-expressing oocytes, but not in water-injected oocytes (Fig. 3A). We initially thought that these BYE-induced currents might be carried by basic amino acids, which, according to a previous study, are putative substrates of PfCRT (21). However, neither histidine, lysine, nor arginine at a concentration of up to 1 mm was able to reproduce the BYE-induced currents in PfCRT-expressing oocytes. Flux experiments conducted with tritiated histidine, lysine, or arginine corroborated the conclusion that PfCRT does not act on these positively charged amino acids. We also could not confirm previous studies suggesting a role of PfCRT in the transport of glutathione, the polyamines spermine and putrescine, choline, tetraethyl ammonium, or glycylsarcosine (supplemental Fig. S3, A and B) (20, 21). The latter two substances are typical substrates of organic cation transporters and oligopeptide carriers, respectively (42, 43). None of these substances induced currents in, or were taken up by, PfCRT-expressing oocytes. Whereas our findings contrast with a functional role of PfCRT as a polyspecific cation transporter, they are consistent with previous studies showing that none of these putative substrates are able to compete with chloroquine for transport via PfCRTDd2 (5).

We suspect that these diverging findings arose from the investigation of different PfCRT constructs. Studies proposing a role of PfCRT in polyspecific cation transport used a PfCRT fusion protein that was modified at both the N- and C-terminal end by the addition of YbeL and a His6 tag (21). YbeL is an uncharacterized E. coli protein of 120 amino acids. It is possible that fusing PfCRT at both ends to a heterologous, possibly enzymatically active polypeptide affected its conformation and membrane topology and hence its functionality and substrate specificity. In contrast, the PfCRT constructs used herein have been validated in several functional studies, providing fundamental insights into PfCRT-mediated drug transport processes (5, 6, 13, 44, 45), although, admittedly, they harbor discreet amino acid replacements needed to remove putative lysosomal trafficking and sorting motifs and ensure expression at the oocyte plasma membrane (5).

After excluding several currently discussed substrates of PfCRT, we explored the possibility of iron being a substrate of PfCRT. The rationale behind this idea was the high concentration of metabolically released iron in the parasite's digestive vacuole of 53 fg/digestive vacuole (46) and the fact that BYE contains 55.3 μg g−1 dry weight of ionic iron (36), which amounts to a total iron concentration of 5 μm in the 0.5% BYE buffer used in the electrophysiological experiments. Several independent lines of evidence suggest that ionic iron is, indeed, a substrate of PfCRT. First, there is evidence from our electrophysiological studies, which show that the addition of the iron chelator DFO to the buffer largely eliminated the signal induced by BYE (Fig. 3B). Moreover, both the ferric and ferrous forms of iron induced inward currents in both PfCRTHB3- and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes (but not in the control water-induced oocytes) (Fig. 4). These iron-induced signals were partially reduced by the addition of verapamil.

Flux experiments substantiated our conclusion that the iron-induced signals represented a transport of iron. As shown in Figs. 5 and 8, PfCRT expression in oocytes led to a significant uptake of both iron forms. Importantly, the uptake of both Fe2+ and Fe3+ was saturable in oocytes expressing either PfCRTDd2 or PfCRTHB3 (Fig. 8). The saturable nature of the uptake kinetics is consistent with carrier-mediated transport of the iron, but it is difficult to reconcile with iron entering the oocyte via a nonspecific leak or via the endogenous non-selective cation conductance. Further excluding a role of the endogenous non-selective cation conductance, iron fluxes were independent of DPC (Fig. 7B). Importantly, iron transport via PfCRTHB3 or PfCRTDd2 was sensitive to verapamil and could be blocked by 50–60% (Fig. 6, A and B). Moreover, chloroquine transport via PfCRTDd2 could be competed for by increasing concentrations of both ferrous and ferric iron (Fig. 6C).

Our finding that verapamil acted on both PfCRTHB3 and PfCRTDd2 might be surprising. However, a functional assay to interrogate the interaction of PfCRT with verapamil has thus far existed only for the chloroquine resistance-mediating PfCRT variants, thus precluding consensus on whether or not verapamil inhibits wild-type PfCRT. Only now, with the finding of PfCRTHB3-expressing oocytes responding to BYE and iron in both electrophysiological and flux assays, have such tools become available. On the basis of these data, we propose that verapamil binding is an intrinsic feature of PfCRT, one that is not limited to certain variants, albeit the affinity to verapamil might reveal variant-specific characteristics. This conclusion is consistent with previous reports showing that verapamil, as a partial mixed type inhibitor of PfCRTDd2, binds to a site distinct from that of chloroquine and other drugs (6).

PfCRTDd2- and PfCRTHB3-expressing oocytes exhibit somewhat different kinetic parameters for Fe2+ transport (Table 1). There was a highly significant difference between the Vmax values for Fe2+ between the PfCRTHB3- and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes, but this difference for Fe3+ was only of borderline significance. Similarly, the Km values were significantly different, as between the PfCRTHB3- and PfCRTDd2-expressing oocytes for Fe2+, but not so for Fe3+. Apparently, PfCRTDd2 has an impaired Fe2+ iron transporting activity, whereas its Fe3+ activity is maintained compared with PfCRTHB3. This might explain the fitness cost incurred by P. falciparum strains harboring PfCRTDd2 or some other geographic PfCRT variants in the absence of a drug pressure (14, 47).

The finding that the two PfCRT variants differed in their ability to transport iron links iron transport to the molecular features of PfCRT itself. That this difference is more marked in the case of Fe2+ might point to ferrous iron as being the form that is a substrate of PfCRT. The individual or combined contribution of the eight amino acid substitutions distinguishing PfCRTDd2 from PfCRTHB3 to the differential iron transport activity is not yet clear and must await crystallographic validation. However, one might extrapolate findings from DMT1 to PfCRT. In the case of DMT1, an asparagine residue seems to coordinate ferrous iron binding (48). On the basis of this observation, one might speculate that the N75E and the N326S substitutions present in PfCRTDd2 selectively affect the ability to transport ferrous iron.

We have to qualify our findings in the sense that they are solely based on functional studies conducted on PfCRT expressed in the heterologous X. laevis oocyte system. The X. laevis oocyte system is a validated tool that has provided fundamental insights into PfCRT-mediated drug transport processes (5, 6, 13, 44, 45). However, recent studies have revealed that PfCRT is posttranslationally modified in the parasite by phosphorylation at four sites and by palmitoylation at one site (49, 50). Whether these posttranslational modifications are conserved in the oocyte systems is unknown, as is the effect of posttranslational modifications on the functionality of PfCRT. We are, therefore, aware that our findings await validation in the parasite. However, the tools to demonstrate iron transport across the parasite's digestive vacuolar membrane have yet to be developed.

If PfCRT is indeed a transporter of iron, what might be its role in the parasite's physiology? The parasite metabolizes extensively the hemoglobin of its host cell and, in doing so, liberates as much as 58 fg of heme-associated iron per single trophozoite (46). 95% of the iron remains heme-associated and eventually biomineralizes to hemozoin in the parasite's digestive vacuole (46). The fate of the remaining 5% iron is less clear. It probably contributes to the labile iron pool, with most of it being chelated in inorganic and/or organic non-heme complexes. Free iron will be mostly in its ferrous state, and very little, if any, will exist as ferric iron at the acidic pH of the digestive vacuole (resting pH ∼5.2 (51)) due to the formation of water-insoluble ferric hydroxide.

By facilitating ferrous iron transport across the digestive vacuolar membrane, PfCRT might mobilize ferrous iron derived from hemoglobin degradation and make it accessible to the parasite's metabolic activities. This model assumes a direction of iron flux via PfCRT from the acid compartment (lumen of the digestive vacuole in the parasite or external medium in the case of oocytes) to the cytoplasm. Our finding that iron flux via PfCRT is pH-dependent and increases with acid pH is consistent with PfCRT extruding iron from the digestive vacuole in a manner driven by the proton electrochemical gradient. Although this is a plausible hypothesis, given that chloroquine and other quinolone-like drugs are transported by PfCRT in association with protons out of the digestive vacuole (5, 6, 10, 11, 13), we cannot exclude the possibility of PfCRT extracting iron from the parasite's cytoplasm and depositing it in the digestive vacuole. Maybe PfCRT can perform both functions, depending on electrochemical gradients and whether or not there is a deficiency or a surplus of iron in the parasite's cytoplasm. Thus, PfCRT might contribute to a network of iron regulatory systems, which, in addition to PfCRT, includes a recently discovered iron transporter of the parasite's endoplasmic reticulum (52, 53).

Experimental procedures

Ethics statements

Ethical approval of the work performed with the Xenopus laevis frogs was obtained from (i) Comité d'Ethique pour l'Experimentation Animale 34 (protocole CEEA34.GP.011.12) and (ii) the Regierungspräsidium Karlsruhe (Aktenzeichen 35-9185 81/G-31/11) in accordance with the German “Tierschutzgesetz.”

Reagents and radiolabeled compounds

Bacto-yeast extract was purchased from BD Biosciences. Other chemicals were provided by Sigma-Aldrich. The following radiolabeled compounds were obtained from American Radiolabeled Chemicals, GE Healthcare, or PerkinElmer Life Sciences: [3H]chloroquine (specific activity 25 Ci mmol−1), 55FeCl3 (specific activity 0.6 Ci mmol−1), l-[2,3,4-3H]arginine (specific activity 42.6 Ci mmol−1), l-[4,5-3H]lysine (specific activity 93.7 Ci mmol−1), l-[14C(U)]histidine (specific activity 320 Ci mmol−1), l-[3,4-3H]glutamic acid (specific activity 49.9 Ci mmol−1), l-[2,3-3H]aspartic acid (specific activity 12.2 Ci mmol−1), l-[3,4,5-3H]leucine (specific activity 108 Ci mmol−1), l-[2,3,4,5-3H]proline (specific activity 75 Ci mmol−1), [14C]TEA (specific activity 55 mCi mmol−1), [3H]choline (specific activity 85.5 Ci mmol−1), [glycine-2-3H]glutathione (specific activity 47 Ci mmol−1), [3H]putrescine (specific activity 60 Ci mmol−1), and [3H]spermine (specific activity 43 Ci mmol−1).

Solutions

Solutions used in electrophysiological studies

ND10 (10 mm NaCl, 86 mm NMDG chloride, 2 mm KCl, 1.0 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2) was buffered with 5 mm HEPES/NaOH for pH 7.5 and with 5 mm MES/Tris base for pH 6.0. If necessary, the osmolarity of the solution was adjusted using 1–2 mm mannitol to match the osmolarity of the ND96 buffer (see below). ND10-mannitol (10 mm NaCl, the appropriate amount of mannitol (replacing 86 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 1.0 mm CaCl2, and 1 mm MgCl2) to maintain osmolarity) was buffered at pH 6.0 with MES/Tris base. Iron-containing solutions were buffered using MES, a buffering agent that, unlike most of Good's buffers, does not form metal chelates (54). In addition, the concentration of CaCl2 was lowered to 0.6 mm when iron was present in the buffer (22). To maintain iron in the divalent or trivalent form, ascorbic acid or NTA, respectively, was added in quadruple molar ratio relative to the respective iron concentration (22).

Solutions used in transport studies

ND96 (96 mm NaCl, 2 mm KCl, 1.8 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2) was buffered with 5 mm MES/Tris base for pH 6.0 for chloroquine transport. For transport studies using iron, the ND96 buffer was modified as described above, and pH was adjusted to 5.5. Buffers used for studies related to ferric iron transport were supplemented with 200 μm ferrocenium hexafluorophosphate to block an endogenous ferrireductase activity present on the oocyte surface (22).

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as described (55). Briefly, 3 days after cRNA injection, total lysates were prepared from X. laevis oocytes by the addition of radioimmunoprecipitation assay-lysis buffer (10 mm HEPES-Na, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) containing protease inhibitors (CompleteTM, Roche Applied Science). After removal of the cellular debris by centrifugation, lysates were mixed with sample buffer (LDS sample buffer NuPAGE, Thermo Scientific). Total protein extracts were size-fractionated using 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. PfCRT was detected using a guinea pig anti-peptide antiserum raised against the N terminus of PfCRT (MKF ASK KNN QKN SSK) (Eurogentec) (dilution 1:1000). As a secondary antibody, a peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-guinea pig antiserum purchased from Dianova (dilution 1:10,000) was used. Membranes were stripped (in PBS containing 1% SDS and 100 mm β-mercaptoethanol for 20 min at room temperature), and tubulin was detected with a monoclonal antibody to α-tubulin (1:1000; Sigma) and a peroxidase-conjugated secondary goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (1:10,000; Dianova). The hybridization signals were quantified using Image Studio Digits version 4.0 (LI-COR).

Immunofluorescence

Three days after cRNA injection, oocytes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde plus PBS for 4 h at room temperature. Fixed cells were washed with 3% BSA plus PBS and then permeabilized with 0.05% Nonidet P-40 plus PBS for 60 min. The rabbit polyclonal antiserum raised against InsP3R-I (H-80) corresponding to amino acids 1894–1973 within the cytoplasmic domain of InsP3R-I (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or the guinea pig anti-PfCRT antiserum (dilution 1:500) was added, and oocytes were incubated overnight at 4 °C. Oocytes were subsequently washed in 3% BSA plus PBS, and the Alexa Fluor 546 anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Invitrogen) or the Alexa Fluor 488 anti-guinea pig secondary antibody (dilution 1:1000) was added and allowed to bind for 90 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the cells were rinsed four times before they were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Images were taken with a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal laser-scanning microscope.

Intracellular ATP determination

The intracellular ATP level of oocytes was determined as described (27). Briefly, whole oocytes were individually mixed with 500 μl of boiling water and kept at 100 °C for 5 min. Samples were then kept on ice until measurement. 2.5 μl was subsequently added to 22.5 μl of 10 mm HEPES-Na, pH 7.3, containing 2 mm MgCl2, and the amount of ATP was determined, using the ATP bioluminescence assay kit CLS II (Roche Applied Science) as instructed by the supplier. Bioluminescence was recorded using the Lumat LB9597 (EG&G Berthold).

PfCRT expression in X. laevis oocytes

Adult female X. laevis frogs (NASCO and Xenopus Express (Vernassal, France)) were anesthetized in a cooled solution of ethyl 3-amino benzoate methanesulfonate (0.1%, w/v) before a surgical partial ovarectomy. Small pieces of ovary were gently shaken at room temperature for 2–3 h in a Ca2+-free ND96 solution supplemented with collagenase 1A (Sigma-Aldrich). After adding CaCl2 (1.8 mm) and carefully washing off the enzyme, defolliculated and healthy-looking stage V-VI oocytes were selected and allowed to recover for a few hours (up to 24 h) before being microinjected. The injected RNA was generated as follows. The codon-optimized coding sequences of PfCRTDd2 and PfCRTHB3 were subcloned in the SP64T expression vector. The resulting SP64-PfCRT plasmid was subsequently linearized using the restriction endonuclease PstI (New England BioLabs GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany) and transcribed in vitro using a mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion, Germany) (6). The obtained cRNA was kept up to 8 weeks (at −80 °C), and diluted in RNase-free water to the desired concentration on the day of the oocyte injection. To inject in each oocyte, the precise volume of 50 nl, precision-bore glass capillary tubes (Microcaps Drummond) were pulled on a vertical puller (PE2, Narishige, Tokyo, Japan) and graduated. These micropipettes were placed on a micromanipulator (Narishige) and connected to a microinjector (Inject+Matic, Geneva, Switzerland). Oocytes were disposed on a mesh tissue in a Petri dish and injected under stereo microscopic control with water alone (control oocytes) or with RNA-containing water. Unless stated otherwise, 30 ng of RNA in 50 nl of RNase-free water or 50 μl of water alone were injected per oocyte (Inject+Matic). Where indicated, oocytes were injected with cRNA coding the divalent metal transporter from rat, rDMT1 (23). The rDMT1 construct was a kind gift from Professor M. Hediger (Bern University, Switzerland). The injected oocytes were incubated at 17 °C for 48–72 h in ND96 for transport assays or in ND10 medium (reduction of NaCl to 10 mm by an equimolar concentration of NMDG or choline chloride) for electrophysiological studies. The incubation media were supplemented with penicillin/streptomycin (100 units/100 μg ml−1).

Two-electrode voltage clamp experiments

Oocytes were preincubated in an acidic ND10 (buffered with MES/Tris base at pH 6.0) solution for 30 min before being examined by two-electrode voltage clamp experiments. Oocytes were subsequently placed in a microchamber and superfused with ND10 (pH 6.0) while being punctured with two low-resistance (0.5–2.0-megaohm), 3 m KCl-filled microelectrodes. The microelectrodes were connected to a current–voltage amplifier (Axoclamp 2B or Dagan CA-1B), and the circuit was closed using an Ag-AgCl pellet. Solution change was commanded electronically, using a laboratory-made device. Whole-cell currents were recorded on a multichart recorder (Arc en Ciel, Sefram, Servofram, France) at a holding membrane potential Vc = −50 mV. Current–voltage relationships (I/V) were obtained in the range −100 to +60 mV (voltage steps of 20-mV increments, 5-s duration from the resting potential), using a Clampex9-generated protocol. The membrane conductance Gm (slope conductance) was calculated from a linear part of the curves. Results were interfaced with Digidata 1322A to a computer and were analyzed with the P-Clamp9 software program (Axon Instruments). In all cases, oocytes from at least three different frogs were analyzed, with the total number of oocytes investigated indicated in the respective figure.

Intracellular Na+ activity

Intracellular Na+ activity α(Na+)i was measured in oocytes by double-barreled ion-selective microelectrodes (ISMs), using the sodium ionophore mixture A (Selectophore), as described previously (26, 56). Briefly, after gentle beveling of the tip, the ISM slope was S = 50–59 mV between a pure 100 mm NaCl solution (which also filled the selective barrel) and a mixed (10 mm NaCl plus 90 mm KCl) solution. ISMs were connected to a high-impedance electrometer (FD 223, WPI, UK), and the circuit was closed by a 1% agar, 1 m KCl bridge. The non-selective barrel was filled with 1 m KCl. α(Na+)i was calculated according to (Na+)i = (Na+)ref × 10exp(VNa − Vm)/S, where (Na+)ref is the Na+ activity in the superfusate (by taking an activity coefficient of 0.79) and VNa is the measured electrochemical potential difference or Na+.

Transport assays

Chloroquine flux assays were performed as described previously (5, 6). Briefly, oocytes were incubated for 60 min at 25 °C in ND96 buffer, pH 6.0, containing 42 nm [3H]chloroquine and 50 μm of unlabeled chloroquine before the amount of chloroquine taken up by each oocyte was determined. Where indicated, chloroquine flux assays were performed in ND10 buffer, pH 5.5. The ND96 buffer system, pH 6.0, was also used for all transport assays pertaining to the biomolecules shown in supplemental Fig. S3 (A and B). Uptakes of iron were performed using 55Fe (2 μm) in a HEPES-free, calcium-reduced ND96, pH 5.5, to avoid metal chelation by HEPES (22) and to prevent a putative competition between divalent metals (23, 54) (see above). The amount of unlabeled iron added is indicated in the figure legends. To stop uptake, the radioactive medium was removed, and oocytes were washed three times in ice-cold buffer. Each oocyte was transferred into a scintillation vial to be lysed by adding 200 μl of a 5% SDS solution. The radioactivity of each sample was measured using a β-scintillation counter. The direction of transport in these assays is from the acidic extracellular medium (in most cases pH 5.5) into the oocyte cytosol (pH ∼7.2), which corresponds to the efflux of drug from the acidic digestive vacuole (pH 5.2) into the parasite cytosol (pH 7.2) (51). Water-injected oocytes were analyzed in parallel, providing information regarding uptake of a particular substance by diffusion and/or endogenous permeation pathways. This value represents the “background” against which the amount of uptake by PfCRT-expressing oocytes was compared. Where indicated, the specific PfCRT-mediated uptake was determined by subtracting the corresponding background uptake measured in water-injected oocytes from that of PfCRT-expressing oocytes. Uptake was performed at 25 °C for 60 min, if not indicated otherwise. In the case of iron uptake, the raw data were not normally distributed. The raw data did, however, follow a log-normal distribution, and we could therefore compute a mean of the logarithms of the individual measurements. We report the data as the antilogarithms of these means of logarithms. In all cases, at least three separate experiments were performed (on oocytes from different frogs), and in each experiment, measurements were made from 8–10 oocytes/treatment.

Statistical analysis

Except where stated otherwise, results are expressed as means ± S.E. of n oocytes obtained from NBR independent biological replicates (different frogs). In the case of electrophysiological studies, n is indicated on the graphs, and NBR = 2–7. In the case of uptake assays, except for the kinetics of iron uptake, n = 24–50 oocytes from 3–5 different frogs. In the case of iron uptake kinetics, n and NBR are indicated in the figure legend. Oocytes obtained from a single frog are considered an independent biological determination. The data were analyzed for statistical significance using the two-tailed t test, the paired t test, the Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on ranks test, or the Holm–Sidak one-way ANOVA test, where appropriate. p values < 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Sigma Plot version 13.0.

Author contributions

N. B., G. P., and M. L. designed the study. N. B., S. B., B. N., S. M. C., C. P. S., and Z. K. performed the experiments. N. B., S. B., B. N., S. M. C., Z. K., C. P. S., W. D. S., G. P., and M. L. analyzed the data. M. L., G. P., and W. D. S wrote the manuscript. All authors participated in discussion and manuscript editing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mathias Hediger for providing an rDMT1-containing plasmid and Carole Baumont for introducing us to iron flux experiments. S. M. C. was a member of the Hartmut Hoffmann-Berling International Graduate School of Molecular and Cellular Biology at Heidelberg University, Germany.

This work was supported by the joint French-German Research Initiative sponsored by the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Grants EVOTRANSPORT/ANR-14-CE35-0012-01 and LA 941/11-1 and PHC PROCOPE Grants 30995WE and ID 57051467. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

This article contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S6.

- PfCRT

- P. falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter

- CLT

- PfCRT-like transporter

- BYE

- bacto-yeast extract

- DFO

- deferoxamine

- DMT1

- divalent metal-ion transporter 1

- rDMT1

- rat DMT1

- DPC

- diphenylamine 2-carboxylic acid

- InsP3R

- inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor

- NMDG

- N-methyl-d-glucamine

- TEA

- tetraethyl ammonium

- VP

- verapamil

- ISM

- ion-selective microelectrode

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

References

- 1. Fidock D. A., Nomura T., Talley A. K., Cooper R. A., Dzekunov S. M., Ferdig M. T., Ursos L. M., Sidhu A. B., Naudé B., Deitsch K. W., Su X. Z., Wootton J. C., Roepe P. D., and Wellems T. E. (2000) Mutations in the P. falciparum digestive vacuole transmembrane protein PfCRT and evidence for their role in chloroquine resistance. Mol. Cell 6, 861–871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Summers R. L., Nash M. N., and Martin R. E. (2012) Know your enemy: understanding the role of PfCRT in drug resistance could lead to new antimalarial tactics. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 69, 1967–1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ecker A., Lehane A. M., Clain J., and Fidock D. A. (2012) PfCRT and its role in antimalarial drug resistance. Trends Parasitol. 28, 504–514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sá J. M., Twu O., Hayton K., Reyes S., Fay M. P., Ringwald P., and Wellems T. E. (2009) Geographic patterns of Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance distinguished by differential responses to amodiaquine and chloroquine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 18883–18889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martin R. E., Marchetti R. V., Cowan A. I., Howitt S. M., Bröer S., and Kirk K. (2009) Chloroquine transport via the malaria parasite's chloroquine resistance transporter. Science 325, 1680–1682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bellanca S., Summers R. L., Meyrath M., Dave A., Nash M. N., Dittmer M., Sanchez C. P., Stein W. D., Martin R. E., and Lanzer M. (2014) Multiple drugs compete for transport via the Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter at distinct but interdependent sites. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 36336–36351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lehane A. M., and Kirk K. (2010) Efflux of a range of antimalarial drugs and “chloroquine resistance reversers” from the digestive vacuole in malaria parasites with mutant PfCRT. Mol. Microbiol. 77, 1039–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sanchez C. P., Rohrbach P., McLean J. E., Fidock D. A., Stein W. D., and Lanzer M. (2007) Differences in trans-stimulated chloroquine efflux kinetics are linked to PfCRT in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 64, 407–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Papakrivos J., Sá J. M., and Wellems T. E. (2012) Functional characterization of the Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine-resistance transporter (PfCRT) in transformed Dictyostelium discoideum vesicles. PLoS One 7, e39569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lehane A. M., Hayward R., Saliba K. J., and Kirk K. (2008) A verapamil-sensitive chloroquine-associated H+ leak from the digestive vacuole in chloroquine-resistant malaria parasites. J. Cell Sci. 121, 1624–1632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lehane A. M., and Kirk K. (2008) Chloroquine resistance-conferring mutations in pfcrt give rise to a chloroquine-associated H+ leak from the malaria parasite's digestive vacuole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 4374–4380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lakshmanan V., Bray P. G., Verdier-Pinard D., Johnson D. J., Horrocks P., Muhle R. A., Alakpa G. E., Hughes R. H., Ward S. A., Krogstad D. J., Sidhu A. B., and Fidock D. A. (2005) A critical role for PfCRT K76T in Plasmodium falciparum verapamil-reversible chloroquine resistance. EMBO J. 24, 2294–2305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Summers R. L., Dave A., Dolstra T. J., Bellanca S., Marchetti R. V., Nash M. N., Richards S. N., Goh V., Schenk R. L., Stein W. D., Kirk K., Sanchez C. P., Lanzer M., and Martin R. E. (2014) Diverse mutational pathways converge on saturable chloroquine transport via the malaria parasite's chloroquine resistance transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, E1759–E1767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Petersen I., Gabryszewski S. J., Johnston G. L., Dhingra S. K., Ecker A., Lewis R. E., de Almeida M. J., Straimer J., Henrich P. P., Palatulan E., Johnson D. J., Coburn-Flynn O., Sanchez C., Lehane A. M., Lanzer M., and Fidock D. A. (2015) Balancing drug resistance and growth rates via compensatory mutations in the Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter. Mol. Microbiol. 97, 381–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Martin R. E., and Kirk K. (2004) The malaria parasite's chloroquine resistance transporter is a member of the drug/metabolite transporter superfamily. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 1938–1949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tran C. V., and Saier M. H. Jr. (2004) The principal chloroquine resistance protein of Plasmodium falciparum is a member of the drug/metabolite transporter superfamily. Microbiology 150, 1–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Warhurst D. C., Craig J. C., and Adagu I. S. (2002) Lysosomes and drug resistance in malaria. Lancet 360, 1527–1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Maughan S. C., Pasternak M., Cairns N., Kiddle G., Brach T., Jarvis R., Haas F., Nieuwland J., Lim B., Müller C., Salcedo-Sora E., Kruse C., Orsel M., Hell R., Miller A. J., et al. (2010) Plant homologs of the Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine-resistance transporter, PfCRT, are required for glutathione homeostasis and stress responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 2331–2336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Meierjohann S., Walter R. D., and Müller S. (2002) Regulation of intracellular glutathione levels in erythrocytes infected with chloroquine-sensitive and chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem. J. 368, 761–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Patzewitz E. M., Salcedo-Sora J. E., Wong E. H., Sethia S., Stocks P. A., Maughan S. C., Murray J. A., Krishna S., Bray P. G., Ward S. A., and Müller S. (2013) Glutathione transport: a new role for PfCRT in chloroquine resistance. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 19, 683–695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Juge N., Moriyama S., Miyaji T., Kawakami M., Iwai H., Fukui T., Nelson N., Omote H., and Moriyama Y. (2015) Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter is a H+-coupled polyspecific nutrient and drug exporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 3356–3361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Illing A. C., Shawki A., Cunningham C. L., and Mackenzie B. (2012) Substrate profile and metal-ion selectivity of human divalent metal-ion transporter-1. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 30485–30496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mackenzie B., Ujwal M. L., Chang M. H., Romero M. F., and Hediger M. A. (2006) Divalent metal-ion transporter DMT1 mediates both H+-coupled Fe2+ transport and uncoupled fluxes. Pflugers Arch. 451, 544–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Solís-Garrido L. M., Pintado A. J., Andrés-Mateos E., Figueroa M., Matute C., and Montiel C. (2004) Cross-talk between native plasmalemmal Na+/Ca2+ exchanger and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-sensitive Ca2+ internal store in Xenopus oocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 52414–52424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sanchez C. P., Stein W. D., and Lanzer M. (2007) Is PfCRT a channel or a carrier? Two competing models explaining chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum. Trends Parasitol. 23, 332–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nessler S., Friedrich O., Bakouh N., Fink R. H., Sanchez C. P., Planelles G., and Lanzer M. (2004) Evidence for activation of endogenous transporters in Xenopus laevis oocytes expressing the Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter, PfCRT. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 39438–39446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bataillé N., Helser T., and Fried H. M. (1990) Cytoplasmic transport of ribosomal subunits microinjected into the Xenopus laevis oocyte nucleus: a generalized, facilitated process. J. Cell Biol. 111, 1571–1582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Newmeyer D. D., Lucocq J. M., Bürglin T. R., and De Robertis E. M. (1986) Assembly in vitro of nuclei active in nuclear protein transport: ATP is required for nucleoplasmin accumulation. EMBO J. 5, 501–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chraïbi A., and Horisberger J. D. (2002) Na self inhibition of human epithelial Na channel: temperature dependence and effect of extracellular proteases. J. Gen. Physiol. 120, 133–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Abriel H., and Horisberger J. D. (1999) Feedback inhibition of rat amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channels expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes. J. Physiol. 516, 31–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Diakov A., and Korbmacher C. (2004) A novel pathway of epithelial sodium channel activation involves a serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase consensus motif in the C terminus of the channel's α-subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 38134–38142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Martin S. K., Oduola A. M., and Milhous W. K. (1987) Reversal of chloroquine resistance in Plasmodium falciparum by verapamil. Science 235, 899–901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cougnon M., Benammou S., Brouillard F., Hulin P., and Planelles G. (2002) Effect of reactive oxygen species on NH4+ permeation in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 282, C1445–C1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gögelein H., and Pfannmüller B. (1989) The nonselective cation channel in the basolateral membrane of rat exocrine pancreas: inhibition by 3′,5-dichlorodiphenylamine-2-carboxylic acid (DCDPC) and activation by stilbene disulfonates. Pflugers Arch. 413, 287–298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Savalas L. R., Gasnier B., Damme M., Lübke T., Wrocklage C., Debacker C., Jézégou A., Reinheckel T., Hasilik A., Saftig P., and Schröder B. (2011) Disrupted in renal carcinoma 2 (DIRC2), a novel transporter of the lysosomal membrane, is proteolytically processed by cathepsin L. Biochem. J. 439, 113–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. BD Biosciences (2006) BD BionutrientsTM Technical Manual, 3rd Ed., BD Biosciences, Sparks, MD [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mylonas C., and Kouretas D. (1999) Lipid peroxidation and tissue damage. In Vivo 13, 295–309 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chaudhry F. A., Krizaj D., Larsson P., Reimer R. J., Wreden C., Storm-Mathisen J., Copenhagen D., Kavanaugh M., and Edwards R. H. (2001) Coupled and uncoupled proton movement by amino acid transport system N. EMBO J. 20, 7041–7051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bakouh N., Benjelloun F., Hulin P., Brouillard F., Edelman A., Chérif-Zahar B., and Planelles G. (2004) NH3 is involved in the NH4+ transport induced by the functional expression of the human Rh C glycoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 15975–15983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fei Y. J., Sugawara M., Nakanishi T., Huang W., Wang H., Prasad P. D., Leibach F. H., and Ganapathy V. (2000) Primary structure, genomic organization, and functional and electrogenic characteristics of human system N 1, a Na+- and H+-coupled glutamine transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23707–23717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Choi I., Aalkjaer C., Boulpaep E. L., and Boron W. F. (2000) An electroneutral sodium/bicarbonate cotransporter NBCn1 and associated sodium channel. Nature 405, 571–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Roth M., Obaidat A., and Hagenbuch B. (2012) OATPs, OATs and OCTs: the organic anion and cation transporters of the SLCO and SLC22A gene superfamilies. Br. J. Pharmacol. 165, 1260–1287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Smith D. E., Clémençon B., and Hediger M. A. (2013) Proton-coupled oligopeptide transporter family SLC15: physiological, pharmacological and pathological implications. Mol. Aspects Med. 34, 323–336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Richards S. N., Nash M. N., Baker E. S., Webster M. W., Lehane A. M., Shafik S. H., and Martin R. E. (2016) Molecular mechanisms for drug hypersensitivity induced by the malaria parasite's chloroquine resistance transporter. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. van Schalkwyk D. A., Nash M. N., Shafik S. H., Summers R. L., Lehane A. M., Smith P. J., and Martin R. E. (2016) Verapamil-sensitive transport of quinacrine and methylene blue via the Plasmodium falciparum chloroquine resistance transporter reduces the parasite's susceptibility to these tricyclic drugs. J. Infect. Dis. 213, 800–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Egan T. J., Combrinck J. M., Egan J., Hearne G. R., Marques H. M., Ntenteni S., Sewell B. T., Smith P. J., Taylor D., van Schalkwyk D. A., and Walden J. C. (2002) Fate of haem iron in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Biochem. J. 365, 343–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mita T., Kaneko A., Lum J. K., Zungu I. L., Tsukahara T., Eto H., Kobayakawa T., Björkman A., and Tanabe K. (2004) Expansion of wild type allele rather than back mutation in pfcrt explains the recent recovery of chloroquine sensitivity of Plasmodium falciparum in Malawi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 135, 159–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pujol-Giménez J., Hediger M. A., and Gyimesi G. (2017) A novel proton transfer mechanism in the SLC11 family of divalent metal ion transporters. Sci. Rep. 7, 6194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Kuhn Y., Sanchez C. P., Ayoub D., Saridaki T., van Dorsselaer A., and Lanzer M. (2010) Trafficking of the phosphoprotein PfCRT to the digestive vacuolar membrane in Plasmodium falciparum. Traffic 11, 236–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jones M. L., Collins M. O., Goulding D., Choudhary J. S., and Rayner J. C. (2012) Analysis of protein palmitoylation reveals a pervasive role in Plasmodium development and pathogenesis. Cell Host Microbe 12, 246–258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kuhn Y., Rohrbach P., and Lanzer M. (2007) Quantitative pH measurements in Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes using pHluorin. Cell Microbiol. 9, 1004–1013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Slavic K., Krishna S., Lahree A., Bouyer G., Hanson K. K., Vera I., Pittman J. K., Staines H. M., and Mota M. M. (2016) A vacuolar iron-transporter homologue acts as a detoxifier in Plasmodium. Nat. Commun. 7, 10403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Labarbuta P., Duckett K., Botting C. H., Chahrour O., Malone J., Dalton J. P., and Law C. J. (2017) Recombinant vacuolar iron transporter family homologue PfVIT from human malaria-causing Plasmodium falciparum is a Fe2+/H+ exchanger. Sci. Rep. 7, 42850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Mackenzie B., Takanaga H., Hubert N., Rolfs A., and Hediger M. A. (2007) Functional properties of multiple isoforms of human divalent metal-ion transporter 1 (DMT1). Biochem. J. 403, 59–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rotmann A., Sanchez C., Guiguemde A., Rohrbach P., Dave A., Bakouh N., Planelles G., and Lanzer M. (2010) PfCHA is a mitochondrial divalent cation/H+ antiporter in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 76, 1591–1606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cougnon M., Bouyer P., Planelles G., and Jaisser F. (1998) Does the colonic H,K-ATPase also act as an Na,K-ATPase? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 6516–6520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.