Abstract

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is characterized by reductions in β-cell function and insulin secretion on the background of elevated insulin resistance. Aerobic exercise has been shown to improve β-cell function, despite a subset of T2D patients displaying “exercise resistance.” Further investigations into the effectiveness of alternate forms of exercise on β-cell function in the T2D patient population are needed. We examined the effect of a novel, 6-wk CrossFit functional high-intensity training (F-HIT) intervention on β-cell function in 12 sedentary adults with clinically diagnosed T2D (54 ± 2 yr, 166 ± 16 mg/dl fasting glucose). Supervised training was completed 3 days/wk, comprising functional movements performed at a high intensity in a variety of 10- to 20-min sessions. All subjects completed an oral glucose tolerance test and anthropometric measures at baseline and following the intervention. The mean disposition index, a validated measure of β-cell function, was significantly increased (PRE: 8.4 ± 3.1, POST: 11.5 ± 3.5, P = 0.02) after the intervention. Insulin processing inefficiency in the β-cell, expressed as the fasting proinsulin-to-insulin ratio, was also reduced (PRE: 2.40 ± 0.37, POST: 1.78 ± 0.30, P = 0.04). Increased β-cell function during the early-phase response to glucose correlated significantly with reductions in abdominal body fat (R2 = 0.56, P = 0.005) and fasting plasma alkaline phosphatase (R2 = 0.55, P = 0.006). Mean total body-fat percentage decreased significantly (Δ: −1.17 0.30%, P = 0.003), whereas lean body mass was preserved (Δ: +0.05 ± 0.68 kg, P = 0.94). We conclude that F-HIT is an effective exercise strategy for improving β-cell function in adults with T2D.

Keywords: pancreas, insulin secretion, exercise, type 2 diabetes, obesity

insulin is an essential glucoregulatory hormone. In the presence of insulin resistance, this pancreatic β-cell-secreted hormone has a diminished ability to drive plasma glucose into peripheral tissues. The subsequent glycemic dysregulation is overcome by β-cell compensation via insulin hypersecretion. In a subset of individuals, however, the β-cell is unable to sustain this compensatory state and eventually undergoes failure. This progression underlies the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and is the topic of several in-depth reviews (8, 12, 15). The investigation of therapies that target recovery of β-cell function in the T2D patient population is of paramount clinical importance, as 21 million American adults have already been diagnosed with the disease (7).

Several groups have demonstrated that exercise has a profound effect on insulin secretion and β-cell function (16, 29), in addition to its already-established influence on insulin sensitivity (17, 28). The specific effects of exercise on β-cell function appear to be dependent on metabolic status and the mode of exercise implemented. We have shown that a 12-wk aerobic exercise intervention improved β-cell function in adults with T2D (31). The same intervention also suppressed insulin hypersecretion in healthy, overweight adults. We further demonstrated that exercise-driven improvements in glycemic control were better predicted by insulin secretion rather than sensitivity (32). Specifically, participants with greater preintervention pancreatic secretory function also had the greatest improvements in glycemic control. When comparing responses with physical training in T2D patients with moderate vs. low secretory capacity, Dela et al. (9) reached a similar conclusion, showing that only the moderate secretors responded favorably to exercise training. From these findings, there appears to be a response dichotomy to exercise in the T2D population, specifically dependent on residual β-cell secretory capacity.

The aforementioned studies used only aerobic exercise training. A recently published study of 8 wk of high-intensity interval training, which has risen in popularity in both the exercise science field and society at large, in adults with T2D showed improvements in β-cell function, despite no changes in insulin secretion or sensitivity (21). The combination of aerobic and resistance training in the Studies Targeting Risk Reduction Interventions through Defined Exercise-Aerobic Training and/or Resistance Training randomized trial resulted in increased β-cell function to a greater extent than either training mode alone in sedentary, obese, nondiabetic adults (1). Combination training or high-intensity training may be able to overcome the apparent resistance to exercise seen in some individuals in aerobic training-only studies, but this has yet to be investigated.

The exercise approach that was developed by CrossFit differs significantly from the exercise protocols used in studies to date and may be described as a functional high-intensity training (F-HIT) protocol. This type of supervised training is defined by constantly varied, functional movements performed at a high intensity and combines resistance training, gymnastics (body weight), and aerobic exercise. Importantly, workouts only require 10–20 min/session and are only performed 3 times/wk (30). To date, there are no published studies that have assessed β-cell function in F-HIT or resistance training within the T2D patient population. We hypothesized that this novel F-HIT intervention program would increase β-cell function in adults with T2D.

METHODS

Subjects.

This pilot, proof-of-principle study, involved 12 adults with clinically diagnosed T2D (8 women, 4 men; glycated hemoglobin test, 8.6 ± 0.7%; 53 ± 2 yr), recruited from the Cleveland metropolitan area. All participants were receiving standard-of-care treatment, including Metformin and diet/exercise education, but none was taking insulin to control his or her diabetes. Exclusion criteria included heart, kidney, liver, thyroid, intestinal, and pulmonary diseases or medications known to affect the outcome variables of the study. All participants underwent medical history, physical exam, and clinical blood work before entering the study. Participants were sedentary (<1 h of exercise/wk) and weight stable (±5 lb.) for the prior 6 mo. Study design and procedures were approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written, informed consent.

Intervention.

Exercise was composed of 6 wk of F-HIT (CrossFit) training, performed at an established gym (Great Lakes CrossFit, Bedford Heights, OH) under the instruction of a certified CrossFit trainer. Groups of two to four participants performed three exercise training sessions per week, which included one high-intensity workout (>85% heart rate maximum), ranging in duration from 10 to 20 min. Over the course of 6 wk, participants were exposed to an array of functional weightlifting, gymnastics, and endurance movements in various combinations. More information about the individual movements and exercises may be found on the CrossFit website (https://www.crossfit.com/exercisedemos/). Post-testing commenced within 36 h after the final exercise bout.

Oral glucose tolerance test.

Participants were provided a standardized mixed-meal dinner (55% carbohydrate, 30% fat, 15% protein) the night before testing. The meal made up 33% of their daily energy requirements, based on the Harris–Benedict equation (13). Medications were withheld 24 h before testing, and the participants also refrained from structured exercise during that time. Following an overnight (~12 h) fast, a baseline blood sample (5 ml) was drawn from an antecubital vein. A 75-g glucose beverage was then consumed within 5 min. Additional blood samples were drawn at 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 min after the glucose was consumed. Aprotinin, EDTA, and dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors were included in subaliquots of plasma and serum, according to the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Blood analysis.

The following clinical blood measures were determined on an automated platform (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN): alkaline phosphatase (ALP), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), plasma glucose, total triglycerides, total cholesterol, VLDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol. Free fatty acids (FFAs) were measured on serum samples collected at 0 and 120 min of the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) using a nonesterified fatty acid enzymatic colorimetric quantification assay (Wako Diagnostics, Richmond, VA). FFA suppression was calculated as the percent reduction in serum FFA from the 0- to 120-min time points (14). Insulin and C-peptide were measured for all OGTT samples via radioimmunoassay (Millipore Sigma, Billerica, MA) and counted on a Beckman Gamma 4000 Counter (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). Intact proinsulin was measured by ELISA (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden), with <0.03 and <0.006% specificity for insulin and C-peptide, respectively. Plasma glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP) were measured on baseline and 30 and 60 min samples using an ELISA (Millipore Sigma). Insulin processing was calculated as the ratio of proinsulin to insulin (6). The early-phase C-peptide secretory response (secretory index), an established predictor of early-phase insulin secretion, was calculated as the ratio of the change in plasma C-peptide and glucose concentrations between baseline (0 min) and 30 min samples during the OGTT (26). Late-phase insulin secretion was calculated as the ratio of the total area under the curve (tAUC) for plasma C-peptide and glucose measures, from 30 to 180 min of the OGTT. An insulin sensitivity index was calculated using the validated Stumvoll equation (37). β-Cell function [disposition index (DI)] was individually calculated as the product of the secretory index and insulin sensitivity index × 103 (2). Unless stated otherwise, secretion and β-cell function here refer to the early-phase secretion index and DI, respectively.

Body composition.

Body composition measures were obtained before and after completion of the intervention. Body weight was determined using standard procedures to the nearest 0.1 kg, averaged over three independent measures. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry was used to determine total and depot-specific body fat, as well as lean mass, with the Lunar iDXA model scanner and software (GE Healthcare, Madison, WI).

Physical performance.

All participants underwent a screening 12-lead ECG submaximal exercise stress test (SensorMedics; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) to assess healthy heart function and safety to exercise. The test was performed on a treadmill at constant speed, while the grade was increased in 2 min stages until the individual reached 80–85% of his or her age-predicted heart rate max. Blood pressure was also recorded during every 2 min stage of the test. A second incremental-graded treadmill exercise test was administered on a separate day and was performed before and after the exercise intervention to measure maximal oxygen consumption (V̇o2max; Jaeger Oxycon Pro; Viasys Healthcare, Yorba Linda, CA) (17). The test was deemed maximal if there was a plateau of V̇o2 despite an increased workload and at least two of the following additional criteria were satisfied: volitional fatigue, heart rate greater than age-predicted maximum, and respiratory exchange ratio of ≥1.10. Blood pressure and heart rate were also monitored during the test. Performance during each exercise training session was recorded by the CrossFit trainer. Days 2 and 18 (final session) consisted of the same sets of exercises with total repetitions recorded: five sets of 1 min of rowing, 1 min of sit-ups, 1 min of squats (no weight), and 1 min of rest. One subject did not complete a postintervention V̇o2max test due to equipment failure, and another subject did not have the number of repetitions recorded for his or her final exercise training session.

Statistics.

Data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Data sets were tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Non-normal data were natural log transformed to approach normality, which was subsequently confirmed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. PRE to POST intervention statistical comparisons were analyzed with a paired two-tailed Student’s t-test. Linear regression analyses between study variables (Δ vs. Δ) were also performed in GraphPad Prism 5, using the Pearson test for correlations. Non-normally distributed Δ data sets were also natural log transformed to approach normality. The accepted significance for each two-tailed test and Pearson correlation was set a priori at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Physiological and metabolic adaptations.

F-HIT intervention effects on subject anthropometrics and fasting plasma measures are listed in Table 1. Body composition changed significantly, with a mean reduction in total body fat percentage (Δ: −1.1 ± 0.3%, P = 0.002), along with trending total body weight loss (Δ: −1.8 ± 1.0 kg, P = 0.09). Exercise capacity was significantly greater after training, with increases in both V̇o2max (Δ: 0.38 ± 0.08 l/min, P = 0.001) and total repetitions completed for standardized training sessions (Δ: 59 ± 8, P < 0.001). Mean fasting plasma measures of glucose, insulin, C-peptide, proinsulin, and FFAs, which are of general clinical importance to patients with T2D, did not change significantly. Measures of liver enzyme levels in the plasma (ALP, AST, ALT) were significantly, or tended to be, reduced. First-phase (0–30 min) and late-phase (30–180 min) plasma glucose, insulin, C-peptide, and proinsulin remained unchanged as well (Table 1).

Table 1.

Anthropometrics and plasma measures

| PRE | POST | Δ | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (M/F) | 12 (5/7) | |||

| Age, yr | 54 ± 2 | |||

| Body composition | ||||

| Body weight, kg | 98.0 ± 3.7 | 96.1 ± 2.7 | −1.8 ± 1.0 | 0.09 |

| Total fat, % | 43.6 ± 1.8 | 42.5 ± 1.8 | −1.1 ± 0.3 | 0.002* |

| Abdominal fat, % | 56.2 ± 1.8 | 55.3 ± 1.7 | −0.9 ± 0.7 | 0.22 |

| Physical performance | ||||

| V̇o2max, l/min | 2.43 ± 0.12 | 2.81 ± 0.15 | 0.38 ± 0.08 | 0.001* |

| Session 2 (PRE) vs. 18 (POST), reps | 223 ± 12 | 282 ± 11 | 59 ± 8 | <0.001* |

| Fasting plasma | ||||

| Glucose, mg/dl | 166 ± 16 | 161 ± 16 | −4.9 ± 3.5 | 0.19 |

| Insulin, µU/ml | 24.3 ± 5.7 | 25.8 ± 4.9 | 1.5 ± 3.7 | 0.69 |

| C-Peptide, ng/ml | 3.3 ± 0.4 | 3.2 ± 0.3 | −0.11 ± 0.13 | 0.41 |

| Proinsulin, pmol/l | 48.4 ± 9.4 | 36.4 ± 5.9 | −11.9 ± 7.7 | 0.15 |

| Free fatty acids, mmol/l | 0.77 ± 0.06 | 0.81 ± 0.07 | 0.04 ± 0.06 | 0.58 |

| ALP, U/l | 76 ± 6 | 69 ± 4 | −7.2 ± 3.5 | 0.06 |

| AST, U/l | 25 ± 3 | 20 ± 2 | −4.4 ± 1.6 | 0.02* |

| ALT, U/l | 27 ± 4 | 22 ± 3 | −5.8 ± 2.4 | 0.03* |

| Oral glucose tolerance test | ||||

| ΔGlucose (0–30 min), mg/dl | 84.2 ± 6.4 | 80.7 ± 8.0 | −3.50 ± 6.01 | 0.57 |

| ΔInsulin (0–30 min), ng/ml | 37.7 ± 9.4 | 47.9 ± 12.4 | 10.2 ± 6.8 | 0.16 |

| ΔC-Peptide (0–30 min), µU/ml | 0.80 ± 0.17 | 0.95 ± 0.21 | 0.15 ± 0.13 | 0.28 |

| ΔProinsulin (0–30 min), pmol/l | 10.9 ± 3.9 | 11.8 ± 3.4 | 0.9 ± 3.0 | 0.77 |

| Glucose tAUC (30–180 min), mg⋅dl−1⋅min−1 | 33,509 ± 2,406 | 32,637 ± 2,177 | −873 ± 1,018 | 0.41 |

| Insulin tAUC (30–180 min), ng⋅ml−1⋅min−1 | 9,466 ± 1,903 | 9,494 ± 2,295 | 27.8 ± 970 | 0.98 |

| C-Peptide tAUC (30–180 min), µU⋅ml−1⋅min−1 | 541 ± 49 | 550 ± 47 | 9.36 ± 10.5 | 0.39 |

| Proinsulin tAUC (30–180 min), pmol⋅l−1⋅min−1 | 9,784 ± 1,807 | 8,186 ± 1,239 | −1,598 ± 835 | 0.08 |

P < 0.05.

Insulin secretion.

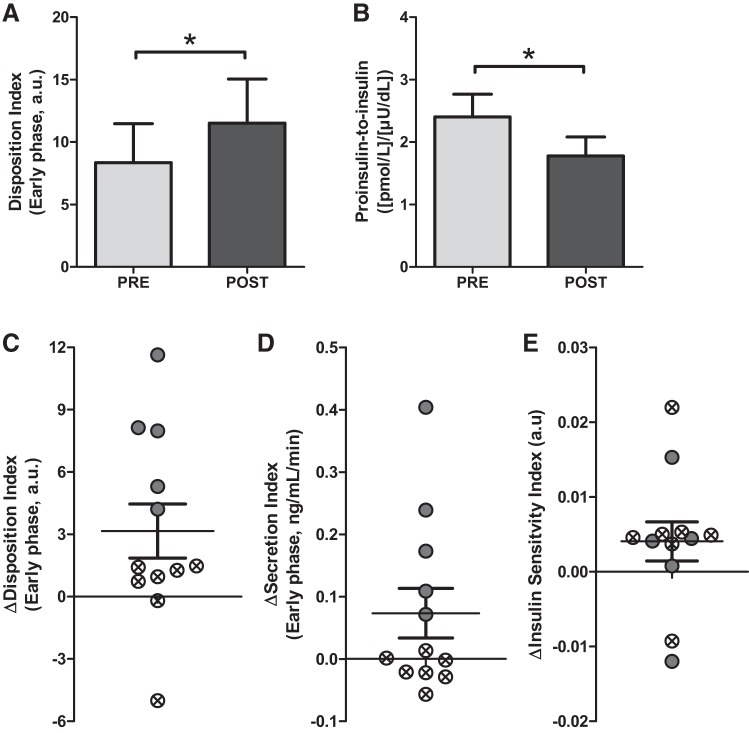

The early-phase DI was significantly improved following the intervention (PRE: 8.4 ± 3.1, POST: 11.5 ± 3.5, P = 0.02; Fig. 1A). Late-phase DI was not increased (PRE: 15.6 ± 3.1, POST: 16.4 ± 2.5, P = 0.65). There was, however, variability in individual responses to the intervention with regard to DI (Fig. 1C). Individuals with ΔDI above and below the mean are indicated. Since DI is the product of early-phase secretion and insulin sensitivity, the individual changes (Δ) for these measures are presented in Fig. 1, D and E. The individual demarcations from Fig. 1C are retained in Fig. 1, D and E to illustrate further the variability in responses to the intervention. These latter data show that improvements in insulin secretion, and not insulin sensitivity, were most likely responsible for the improvement in DI. The proinsulin/insulin ratio, a measure of insulin-processing inefficiency, was reduced after the intervention (PRE: 2.40 ± 0.37, POST: 1.78 ± 0.30, P = 0.04; Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

A: early-phase pancreatic cell function PRE to POST intervention, presented as the mean disposition index. B: insulin-processing inefficiency expressed as the ratio between fasting proinsulin and insulin. C: individual changes with means ± SE. DI change with individuals with changes below the mean are indicated with crossed circles; DI change with individuals with changes above the mean are indicated with filled circles. Individual changes in secretion (D) and sensitivity (E), keeping the same individual demarcations used in C. *P < 0.05; n = 12.

Incretin and FFA responses.

Fasting GLP-1 (PRE: 3.32 ± 0.65, POST: 3.46 ± 0.72 ng/ml, P = 0.78) and GIP (PRE: 40.5 ± 7.0, POST: 46.9 ± 7.0 ng/ml, P = 0.14) levels remained unchanged, as well as tAUC for the first 60 min of the OGTT: GLP-1 (PRE: 558 ± 98, POST: 477 ± 88 ng⋅ ml−1⋅min−1, P = 0.58), GIP (PRE: 10,903 ± 1,502, POST: 11,645 ± 1,257 ng⋅ml−1⋅min−1, P = 0.38). The intervention did not significantly alter fasting FFA levels (Table 1) or FFA suppression (PRE: −78.4 ± 3.8, POST: −78.5 ± 5.3%, P = 0.98).

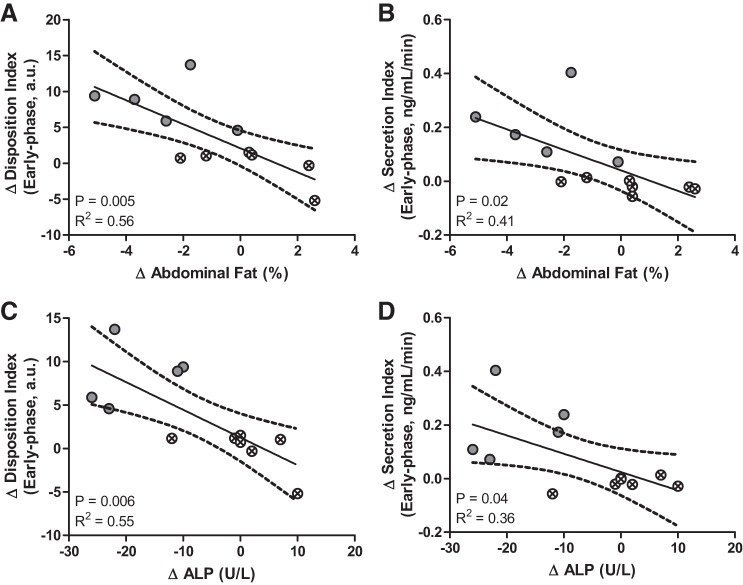

Correlations.

Based on correlation analyses, changes in body composition and ALP correlated significantly with β-cell function and secretion. These data are presented in Fig. 2, with linear regressions and 95% confidence intervals plotted for each Δ vs. Δ correlation. The individual demarcations from Fig. 1 for individual responses in early-phase β-cell function are kept in Fig. 2. This representation further emphasizes the significant correlations between changes in β-cell function and insulin secretion and decreases in abdominal body fat and lowered fasting serum ALP levels. Individual changes in the fasting proinsulin/insulin ratio, another measure of β-cell function, did not correlate significantly with any study variables.

Fig. 2.

Correlations of changes in early-phase β-cell function (A and C) and secretion (B and D) vs. abdominal fat percentage (A and B) and fasting ALP (C and D). Linear regression is shown with a 95% confidence interval with Pearson correlation coefficient of determination (R2) and significant P value; n = 12.

Subgroup analysis.

Figure 2C shows the spread of individual responses to the F-HIT intervention based on the DI-derived β-cell function index. Subgroup analyses were performed to compare the individuals demarcated in Fig. 1 as above the mean (“responders,” n = 5) vs. below the mean (“nonresponders,” n = 7). Participants in the responder subgroup were all women, with no significant differences from the nonresponders in terms of age or body composition. This responder subgroup had higher PRE intervention fasting plasma ALP levels (92 ± 5 vs. 64 ± 7 U/l, P = 0.008), as well as higher fasting C-peptide levels (4.0 ± 0.3 vs. 2.7 ± 0.5 ng/dl, P = 0.05). This subgroup also had better overall glucose tolerance, as tAUC (0–180 min) glucose was lower for this subgroup, PRE (33,603 ± 2,228 vs. 44,157 ± 4,060 mg⋅dl−1⋅min−1, P = 0.05) and POST (32,242 ± 2,051 vs. 43,290 ± 3,502 mg⋅dl−1⋅min−1, P = 0.02) intervention. Secretory capacity, expressed as C-peptide tAUC (0–180 min), was also greater in the responder subgroup, PRE (792.4 ± 54.0 vs. 550.8 ± 73.9 ng⋅ml−1⋅min−1, P = 0.03) and POST (787.0 ± 44.5 vs. 569.0 ± 75.0 ng⋅ml−1⋅min−1, P = 0.03) intervention. Early-phase secretion changes were significantly greater in the responder subgroup (0.20 ± 0.06 vs. −0.02 ± 0.01 ng⋅ml−1⋅mM−1, P = 0.02), which is apparent from the distribution of individual changes in secretion presented in Fig. 1D. Congruent with the correlations shown in Fig. 2, fasting plasma ALP levels (−18.4 ± 3.3 vs. 0.9 ± 2.6 U/l, P = 0.002) and abdominal fat (−2.6 ± 0.85 vs. 0.40 ± 0.65%, P = 0.02) were significantly reduced in the responder subgroup. Following the intervention, the responder subgroup also had lower fasting plasma glucose (126 ± 11 vs. 187 ± 22 mg/dl, P = 0.04).

DISCUSSION

The determination of β-cell function in humans poses specific challenges, as only indirect plasma metabolite measures are generally possible. The OGTT has emerged as an efficient and effective method for assessing pancreatic insulin secretion (36). However, insulin secretion is tied directly to insulin sensitivity in a classic hyperbolic relationship (4). The DI, which is the mathematical product of secretion and sensitivity, has thus been clinically accepted and validated as a measure of β-cell function in humans (33). Here, we show that exercise at high intensity for as little as 10–20 min/day, 3 days/wk for 6 wk, improves β-cell function in adults with T2D (Fig. 1A). The fasting proinsulin/insulin ratio, representing the processing inefficiency of insulin within the β-cell, was also significantly reduced following the intervention (Fig. 1B), providing further evidence for improved β-cell function.

Despite the achievement of mean improvements in β-cell function, overall glucose tolerance was not significantly changed. Following a more traditional, 3-mo aerobic exercise intervention in T2D patients, Dela et al. (9) used a subgroup analysis to show that only participants with residual β-cell secretory capacity (defined as “moderate secretors”) had significantly improved β-cell function, despite no changes in glucose tolerance. We also found variability in individual changes in DI, where some participants had limited changes and even reductions in DI in response to the intervention. Therefore, we used a similar subgroup analysis approach to delineate possible factors that might contribute to these differences. This analysis revealed that the responder subgroup did indeed show improved glucose tolerance, lower glucose tAUC, and fasting glucose POST intervention, following the intervention, in contrast to the nonresponder subgroup. These data highlight that participants who did not appreciably improve their β-cell function also did not experience improvements in glucose tolerance.

Resistance to the beneficial effects of exercise could be due to underperformance or compensatory lifestyle changes, as some research groups have suggested (20, 24, 35). This variability in response to lifestyle intervention has been noted before (5). In this study, two measures of physical performance improved very significantly in response to the intervention (Table 1), but neither β-cell function nor secretion significantly correlated with either of these measures. Within the subgroup analysis, there were also no differences between “training volume” or the total number of repetitions in comparative sessions between either of the two subgroups. As a result, we cannot attribute response variability specifically to differences in training effort. Instead, as our previously published (32) and currently presented data suggest, residual β-cell secretory capacity is required for exercise (independent of mode) to improve β-cell function and glycemic control effectively. Longer exercise interventions, combined with strict dietary guidelines, may be able to drive improvements in β-cell function in patients with more severe T2D who display resistance to the exercise modes studied to date (25). However, if nonresponse is driven by genetic factors, as Stephens and Sparks (34) and Lessard et al. (20) suggest, then the modification of lifestyle only may not be a sufficient therapeutic approach.

The intervention was quite effective at reducing total body fat, with trending reductions in body weight. Notably, lean mass was preserved (Δ: 0.05 ± 0.68 kg, P = 0.94), indicating that any changes in body weight were due to reductions in fat mass. We also found that reductions in abdominal fat correlated significantly with changes in both β-cell function (R2 = 0.56, P = 0.005) and secretion (R2 = 0.41, P = 0.02; Fig. 2). Accumulation of adipose tissue in the abdominal region has been linked to increased insulin resistance (18) and correlates closely with increased β-cell dysfunction (40), highlighting the negative role of fat in this region on metabolic function. Potential mechanisms include increased plasma FFAs driving lipotoxicitiy of the β-cell (3). However, we did not see any significant statistical association between change in FFAs and β-cell function. We recognize that fasting levels of FFAs do not adequately represent the dynamic regulation of lipolysis (38). However, the percent suppression of plasma FFAs from min 0 to 120 of the OGTT also remained unchanged after the intervention. We have previously reported that exercise and diet intervention-induced improvements in β-cell function among adults with T2D were significantly correlated with changes in GIP (31). However, the incretin hormone levels of GLP-1 and GIP remained unchanged in this study, suggesting that some other mechanism is driving improved β-cell function after this type of intervention.

Many patients with T2D also have accompanying nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocyte apoptosis, which we (10) and others (27) have shown can be reduced by exercise (aerobic and resistance training). Mean plasma AST and ALT levels, which are clinical measures of liver hepatocyte apoptosis, were significantly reduced following the intervention (Table 1), suggesting overall improvements in liver function (11). Fasting ALP also tended to decrease. The correlations in Fig. 2 and our subgroup analyses reveal that in the responder subgroup, ALP levels were significantly elevated PRE intervention but markedly reduced POST intervention. Cross-sectional analysis of plasma ALP levels show that there appears to be no link to sex (41), despite the sex differences between the two subgroups. The source of circulating ALP, which may be of liver, bone, or intestinal origin, was not specifically identified in the clinical assay performed. As a result, we are unable to conclude whether ALP levels were indicative of changes in liver, gut, or bone function. The limited available literature on the topic of ALP in T2D is conflicting. One study determined that bone is the predominant source of elevated ALP in T2D (23), although this is not a consistent observation (39). In a mouse model, a high fat diet increases serum ALP levels, but ALP was unaffected by exercise training, despite protecting the mice from liver steatosis and loss of β-cell function (22). Our data are contrary to these animal model findings, highlighting the need to investigate further the role of this enzyme in diabetes and exercise, especially as it relates to β-cell function.

This was a pilot proof-of-principle study investigating the efficacy of a 6-wk F-HIT lifestyle intervention in adults with T2D, and hence, limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size and lack of comparative groups, in the form of a control group or groups participating in alternative forms of exercise. Instead, we designed the study using an internal validity paradigm, where each participant’s PRE intervention served as the control for the POST intervention testing results. Second, we note that from a technical perspective, the use of the hyperglycemic clamp technique would have provided a more in-depth determination of pancreatic function.

There is little scientific doubt that exercise is beneficial, yet adults with T2D may find it difficult to adhere to a strict exercise regimen, citing “lack of time” as one of their primary barriers (19). F-HIT programs, such as CrossFit, may address this barrier by providing structure, supervision, and accountability, with a minimal time commitment (10–20 min/session, 3 times/wk). Additionally, no adverse events or injuries were reported by participants throughout the course of the study. Therefore, we conclude that F-HIT is a safe and effective exercise approach by which adults with T2D may improve their β-cell secretory function, given that residual β-cell secretory capacity is preserved. Here, we have identified that changes in plasma ALP levels and abdominal adiposity appear to be additional delineating factors in determining the efficacy of exercise-mediated improvements in β-cell function. Larger training studies may shed important insight into the variability in responses to exercise observed in the T2D patient population and subsequently, to develop the most effective exercise treatment options for these patients.

GRANTS

Support for this research was provided by an investigator-initiated grant from CrossFit (to J. P. Kirwan), Cleveland Clinic Research Support Award RPC 2013-1010, and National Institutes of Health, National Center for Research Resources, Grant UL1RR024989.

DISCLOSURES

J. A. Foucher has received consulting fees from CrossFit. S. Nieuwoudt, C. E. Fealy, A. R. Scelsi, S. K. Malin, M. Pagadala, M. Rocco, B. Burguera, and J. P. Kirwan have no conflicts of interest relative to this work. CrossFit marketing provided no input to the data analysis, interpretation, or writing of this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.N., C.E.F., J.A.F., A.R.S., S.K.M., and J.P.K. conceived and designed research; S.N., C.E.F., J.A.F., A.R.S., S.K.M., M.P., M.R., and B.B. performed experiments; S.N., C.E.F., M.R., and B.B. analyzed data; S.N., C.E.F., and J.P.K. interpreted results of experiments; S.N. prepared figures; S.N. drafted manuscript; S.N., C.E.F., J.A.F., A.R.S., and J.P.K. edited and revised manuscript; S.N., C.E.F., J.A.F., A.R.S., S.K.M., B.B., and J.P.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Patrick Flannery of the Great Lakes CrossFit affiliate gym in Bedford Heights, Ohio, for supervising exercise sessions, ensuring safety, and monitoring participant progress.

REFERENCES

- 1.AbouAssi H, Slentz CA, Mikus CR, Tanner CJ, Bateman LA, Willis LH, Shields AT, Piner LW, Penry LE, Kraus EA, Huffman KM, Bales CW, Houmard JA, Kraus WE. The effects of aerobic, resistance, and combination training on insulin sensitivity and secretion in overweight adults from STRRIDE AT/RT: a randomized trial. J Appl Physiol (1985) 118: 1474–1482, 2015. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00509.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahrén B, Pacini G. Importance of quantifying insulin secretion in relation to insulin sensitivity to accurately assess beta cell function in clinical studies. Eur J Endocrinol 150: 97–104, 2004. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1500097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergman RN, Ader M. Free fatty acids and pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Trends Endocrinol Metab 11: 351–356, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S1043-2760(00)00323-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergman RN, Finegood DT, Ader M. Assessment of insulin sensitivity in vivo. Endocr Rev 6: 45–86, 1985. doi: 10.1210/edrv-6-1-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouchard C, Rankinen T. Individual differences in response to regular physical activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 33, Suppl: S446–S451, 2001. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breuer TG, Menge BA, Banasch M, Uhl W, Tannapfel A, Schmidt WE, Nauck MA, Meier JJ. Proinsulin levels in patients with pancreatic diabetes are associated with functional changes in insulin secretion rather than pancreatic beta-cell area. Eur J Endocrinol 163: 551–558, 2010. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2014: Estimates of Diabetes and Its Burden in the United States. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dagogo-Jack S, Santiago JV. Pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes and modes of action of therapeutic interventions. Arch Intern Med 157: 1802–1817, 1997. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1997.00440370028004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dela F, von Linstow ME, Mikines KJ, Galbo H. Physical training may enhance beta-cell function in type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 287: E1024–E1031, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00056.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fealy CE, Haus JM, Solomon TP, Pagadala M, Flask CA, McCullough AJ, Kirwan JP. Short-term exercise reduces markers of hepatocyte apoptosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Appl Physiol (1985) 113: 1–6, 2012. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00127.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forlani G, Di Bonito P, Mannucci E, Capaldo B, Genovese S, Orrasch M, Scaldaferri L, Di Bartolo P, Melandri P, Dei Cas A, Zavaroni I, Marchesini G. Prevalence of elevated liver enzymes in type 2 diabetes mellitus and its association with the metabolic syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest 31: 146–152, 2008. doi: 10.1007/BF03345581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerich JE. Is insulin resistance the principal cause of type 2 diabetes? Diabetes Obes Metab 1: 257–263, 1999. doi: 10.1046/j.1463-1326.1999.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris JA, Benedict FG. A biometric study of human basal metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 4: 370–373, 1918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.4.12.370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holt HB, Wild SH, Wood PJ, Zhang J, Darekar AA, Dewbury K, Poole RB, Holt RI, Phillips DI, Byrne CD. Non-esterified fatty acid concentrations are independently associated with hepatic steatosis in obese subjects. Diabetologia 49: 141–148, 2006. doi: 10.1007/s00125-005-0070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kahn SE. The importance of the beta-cell in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Med 108, Suppl 6a: 2S–8S, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00336-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirwan JP, Kohrt WM, Wojta DM, Bourey RE, Holloszy JO. Endurance exercise training reduces glucose-stimulated insulin levels in 60- to 70-year-old men and women. J Gerontol 48: M84–M90, 1993. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.3.M84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirwan JP, Solomon TP, Wojta DM, Staten MA, Holloszy JO. Effects of 7 days of exercise training on insulin sensitivity and responsiveness in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297: E151–E156, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00210.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohrt WM, Kirwan JP, Staten MA, Bourey RE, King DS, Holloszy JO. Insulin resistance in aging is related to abdominal obesity. Diabetes 42: 273–281, 1993. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.2.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korkiakangas EE, Alahuhta MA, Husman PM, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Taanila AM, Laitinen JH. Motivators and barriers to exercise among adults with a high risk of type 2 diabetes—a qualitative study. Scand J Caring Sci 25: 62–69, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00791.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lessard SJ, Rivas DA, Alves-Wagner AB, Hirshman MF, Gallagher IJ, Constantin-Teodosiu D, Atkins R, Greenhaff PL, Qi NR, Gustafsson T, Fielding RA, Timmons JA, Britton SL, Koch LG, Goodyear LJ. Resistance to aerobic exercise training causes metabolic dysfunction and reveals novel exercise-regulated signaling networks. Diabetes 62: 2717–2727, 2013. doi: 10.2337/db13-0062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madsen SM, Thorup AC, Overgaard K, Jeppesen PB. High intensity interval training improves glycaemic control and pancreatic β cell function of type 2 diabetes patients. PLoS One 10: e0133286, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marques CM, Motta VF, Torres TS, Aguila MB, Mandarim-de-Lacerda CA. Beneficial effects of exercise training (treadmill) on insulin resistance and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in high-fat fed C57BL/6 mice. Braz J Med Biol Res 43: 467–475, 2010. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2010007500030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maxwell DB, Fisher EA, Ross-Clunis HA III, Estep HL. Serum alkaline phosphatase in diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Nutr 5: 55–59, 1986. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1986.10720112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melanson EL, Keadle SK, Donnelly JE, Braun B, King NA. Resistance to exercise-induced weight loss: compensatory behavioral adaptations. Med Sci Sports Exerc 45: 1600–1609, 2013. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31828ba942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montero D, Lundby C. Refuting the myth of non-response to exercise training: ‘non-responders’ do respond to higher dose of training. J Physiol 595: 3377–3387, 2017. doi: 10.1113/JP273480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Polonsky KS, Rubenstein AH. C-Peptide as a measure of the secretion and hepatic extraction of insulin. Pitfalls and limitations. Diabetes 33: 486–494, 1984. doi: 10.2337/diab.33.5.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shamsoddini A, Sobhani V, Ghamar Chehreh ME, Alavian SM, Zaree A. Effect of aerobic and resistance exercise training on liver enzymes and hepatic fat in Iranian men with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepat Mon 15: e31434, 2015. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.31434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Wasserman DH, Castaneda-Sceppa C, White RD. Physical activity/exercise and type 2 diabetes: a consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 29: 1433–1438, 2006. doi: 10.2337/dc06-9910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Slentz CA, Tanner CJ, Bateman LA, Durheim MT, Huffman KM, Houmard JA, Kraus WE. Effects of exercise training intensity on pancreatic beta-cell function. Diabetes Care 32: 1807–1811, 2009. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smith MM, Sommer AJ, Starkoff BE, Devor ST. Crossfit-based high-intensity power training improves maximal aerobic fitness and body composition. J Strength Cond Res 27: 3159–3172, 2013. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e318289e59f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Solomon TP, Haus JM, Kelly KR, Rocco M, Kashyap SR, Kirwan JP. Improved pancreatic beta-cell function in type 2 diabetic patients after lifestyle-induced weight loss is related to glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide. Diabetes Care 33: 1561–1566, 2010. doi: 10.2337/dc09-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Solomon TP, Malin SK, Karstoft K, Kashyap SR, Haus JM, Kirwan JP. Pancreatic β-cell function is a stronger predictor of changes in glycemic control after an aerobic exercise intervention than insulin sensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98: 4176–4186, 2013. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Solomon TP, Malin SK, Karstoft K, Knudsen SH, Haus JM, Laye MJ, Pedersen M, Pedersen BK, Kirwan JP. Determining pancreatic β-cell compensation for changing insulin sensitivity using an oral glucose tolerance test. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 307: E822–E829, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00269.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stephens NA, Sparks LM. Resistance to the beneficial effects of exercise in type 2 diabetes: are some individuals programmed to fail? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100: 43–52, 2015. doi: 10.1210/jc.2014-2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stephens NA, Xie H, Johannsen NM, Church TS, Smith SR, Sparks LM. A transcriptional signature of “exercise resistance” in skeletal muscle of individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 64: 999–1004, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stumvoll M, Fritsche A, Häring H. The OGTT as test for beta cell function? Eur J Clin Invest 31: 380–381, 2001. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2001.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stumvoll M, Mitrakou A, Pimenta W, Jenssen T, Yki-Järvinen H, Van Haeften T, Renn W, Gerich J. Use of the oral glucose tolerance test to assess insulin release and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care 23: 295–301, 2000. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swislocki AL, Chen YD, Golay A, Chang MO, Reaven GM. Insulin suppression of plasma-free fatty acid concentration in normal individuals and patients with type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes. Diabetologia 30: 622–626, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tibi L, Collier A, Patrick AW, Clarke BF, Smith AF. Plasma alkaline phosphatase isoenzymes in diabetes mellitus. Clin Chim Acta 177: 147–155, 1988. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(88)90136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Utzschneider KM, Carr DB, Hull RL, Kodama K, Shofer JB, Retzlaff BM, Knopp RH, Kahn SE. Impact of intra-abdominal fat and age on insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function. Diabetes 53: 2867–2872, 2004. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.11.2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Hoof VO, Hoylaerts MF, Geryl H, Van Mullem M, Lepoutre LG, De Broe ME. Age and sex distribution of alkaline phosphatase isoenzymes by agarose electrophoresis. Clin Chem 36: 875–878, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]