Abstract

HIV/STI incidence has shifted to a younger demographic, comprised disproportionately of gay and bisexual men, transgender women, and people of color. Recognizing the importance of community organizing and participatory engagement during the intervention planning process, we describe the steps taken to engage diverse constituents (e.g., youth, practitioners) during the development of a structural-level HIV/STI prevention and care initiative for young sexual and gender minorities in Southeast Michigan. Our multi-sector coalition (MFierce; Michigan Forward in Enhancing Research and Community Equity) utilized a series of community dialogues to identify, refine, and select programmatic strategies with the greatest potential. Evaluation data (N=173) from the community dialogues highlighted constituents’ overall satisfaction with our elicitation process. Using a case study format, we describe our community dialogue approach, illustrate how these dialogues strengthened our program development, and provide recommendations that may be used in future community-based program planning efforts.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, coalitions, program development

Community organizing is a valuable process that helps practitioners work alongside communities to identify shared challenges and opportunities, and propose and implement strategies to improve well-being (Minkler, 2012). Researchers and practitioners have underscored the importance of promoting multisector participation during the program planning process (Eng & Blanchard, 2006; Harper, Willard, Ellen & ATN, 2011; Rhodes, 2014; Suarez-Balcazar & Harper, 2005; Ziff, Willard, Harper, Bangi, Johnson, & Ellen, 2010). Multisector participation allows diverse constituents in a community to voice their needs and perspectives, to assess existing power dynamics across stakeholders, and to supplement and triangulate the social, historical, and epidemiological data locally available (Alcantara, Harper, & Keys, 2015; Harper, Bangi, Contreras, Pedraza, Tolliver, & Vess, 2004; Lantz, Viruell-Fuentes, Israel, Softley & Guzman, 2001). Partnerships between public health departments, university researchers, community-based organizations, and community members, for example, have been found to promote the development and implementation of public health solutions that are multi-sectoral and community-driven (Ellen, Greenberg, Willard et al., 2015; Israel, Coombe, Cheezum, Schulz, McGranaghan, Lichtenstein, Reyes, Clement & Burris, 2010; Miller, Janulis, Reed, Harper, Ellen, Boyer, & ATN, 2016; Suarez-Balcazar, Harper, & Lewis, 2005). In pooling their resources and expertise, these partnerships may be better equipped to recognize the array of barriers to optimal prevention and care, and to develop structural and community interventions aimed at reducing systemic deficiencies (Doll, Harper, Robles-Schrader et al., 2012; Ziff, Harper, Chutuape et al., 2006).

The 2015 United States National HIV/AIDS Strategy recognized the importance of using community-organizing approaches to inform and implement multilevel interventions that address HIV/STI disparities in vulnerable communities and populations. Young gay, bisexual and other MSM and transgender women (henceforth referred to as YGBMTW) account for a large proportion of new HIV/STI cases in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2017). HIV/STI inequities observed across YGBMTW populations have been linked to an array of psychosocial factors, including the social and built environment (Bauermeister, Connochie, Eaton, Demers & Stephenson, 2017), the absence of comprehensive sex education (Pingel, Thomas, Harmell & Bauermeister, 2013), and limited availability of culturally competent HIV/STI testing and care (Bauermeister, Pingel, Jadwin-Cakmak, Meanley, Alapati, Moore, Lowther, Wade & Harper, 2015; Tanner, Philbin, Duval, Ellen, Kapogiannis, & Fortenberry, 2014). These processes of marginalization may affect individuals’ social mobility, create psychological distress and social isolation, promote the adoption of negative coping behaviors (e.g., substance use), and disrupt access to community resources and social capital (Bauermeister, Goldenberg, Connochie, Jadwin-Cakmak, & Stephenson, 2016; Bruce, Harper, & ATN, 2011; Garofalo, Ozmer, Sullivan, Doll, & Harper, 2007; Harper, 2007).

The disproportionate burden of HIV/STI among YGBMTW is even greater when stratified by race/ethnicity and age, where racial/ethnic minorities and adolescents and young adults between the ages of 13 and 29 account for the majority of new infections (CDC, 2017). Intersectional perspectives have highlighted the exacerbation of these psychosocial factors when individuals belong to multiple minority groups, as they may experience marginalization from both their racial/ethnic and sexual communities (Jamil, Harper, Fernandez, & ATN, 2009; Wilson & Harper, 2013). These data underscore the importance of developing interventions that meet and address YGBMTW’s HIV/STI prevention needs effectively. Thus, consistent with a community-organizing framework, program-planning efforts must identify the structural and community factors that fuel these disparities, and propose sustainable, high-impact solutions that are reflective of communities often times underrepresented, marginalized, or stigmatized (Harper, 2007; Miller et al., 2016; Robles-Schrader, Harper, Purnell, Monares, & the ATN, 2012).

Through the support of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Community Approaches to Reducing STDs program, we formed a coalition (Michigan Forward in Enhancing Research and Community Equity; MFierce) comprised of youth advisors, health department officials, community organizations, and university researchers in August 2014. As the MFierce coalition prepared for the community dialogues, however, we realized how little existed with regard to concrete, descriptive examples of community organizing processes. While many frameworks and activity suggestions are provided in the literature (see e.g., Minkler, 2012 and Israel et al., 2010), few depict the step-by-step process undertaken in the context of an actual initiative or program planning effort, especially at the structural level (for an exception, see Ziff et al., 2006). In part, this absence may be due to the recognition that each community and its issues is unique; there is no “one-size-fits-all” process activity. Nevertheless, we found ourselves desiring greater examples and prior models that could guide our efforts. We imagine that in the midst of the time, energy and resources that must be devoted to effective organizing, the detailed documentation and description of process may be a luxury for some practitioners and community members; thus, we wished to offer a description of our year-long process in hopes of aiding other community groups interested in similar initiatives.

Creating spaces where diverse stakeholders can explore and plan for strategies to address HIV/STI in their region is critical. Aligning with the U.S. National HIV/AIDS Strategy’s call for community organizing efforts, the goal of our manuscript is to describe the community organizing process employed in the greater Detroit-Ann Arbor-Flint Combined Statistical Area (hereafter referred to as Southeast Michigan) during the development of a structural initiative geared to reduce HIV/STIs among YGBMTW in the region. Our manuscript has three objectives. First, we describe how we elicited multisector participation prior to developing our program plan. Second, we share process evaluation data from our iterative community dialogues across the region. Finally, we offer lessons learned during the development and implementation of our strategy.

METHODS

Description of the Partnership

MFierce utilizes a community-based participatory research approach to engage researchers and community partners through shared decision-making. This community engagement approach offered an alternative to traditional research by challenging the notion of “researcher-as-expert” and centering community expertise and lived experience. Participatory research utilizes many principles including co-learning, power-sharing, building community capacity, focusing on the local relevance of health problems, and relying upon iterative processes (Minkler, 2012; Israel et al., 2010). These last two principles in particular were central to MFierce’s process of determining the specific local and structural focus of its efforts. Overall, our shared goal is to design and implement structural change strategies over three years and improve testing, diagnosis, and treatment of STIs among YGBMTW living in Southeast Michigan.

Our coalition has three governing bodies: Youth Advisory Board (YAB), a Steering Committee of Agency Leaders (SC), and researchers from a research center (SL) from a local university. Each group embodies a particular set of roles, responsibilities and expertise that makes the coalition as a whole stronger than the sum of its parts. In Year 1 (the program planning year), the YAB has had eight members, all of whom identify as sexual (e.g., gay/bisexual men) and/or gender (e.g., transgender women, agender/woman thing) minorities and who live in different parts of Southeast Michigan. The YAB members range in age from 19 to 29 years old. Four YAB members identify as Black, one as Latino, two as White, and one as Mixed Race. The role of the YAB is to advise with regard to project direction and activities; their responsibilities include contributing to decision-making processes, bimonthly meeting attendance, participation and leadership in community activities, feedback on all materials created for project dissemination, and contributions to a collective vision.

The SC has ten members representing seven agencies, including three AIDS Service Organizations, two LGBTQ organizations, and the Detroit Department of Health and Wellness Promotion, and the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services. In terms of racial identity, four SC members identify as Black, five as White, and one as Latina. The role of the SC is to provide a general sounding board for the YAB and research team in terms of the implementation feasibility of chosen project activities. Their responsibilities include completing regular assessments of process and content, actively participating in decision-making processes related to program development, contributing to the project evaluation, attending bimonthly meetings, and offering feedback on all project materials.

Finally, the university coordination/research team includes two faculty members, a project director, and several graduate research assistants. Of the eight research team members, one identifies as Black, four as White, two as Latino, and one as Arab American. Six identify as gay, one as straight, and one as bisexual. They range in age from 25 to 53 years old. The overall role of the research team is to coordinate project activities, provide expertise on sexual and gender minority sexual health, and ensure that the direction of the project is responsive to all grantee requirements. During Year 1, their responsibilities primarily focused on meeting coordination, evaluation of community organizing process, reporting requirements, and facilitation of the program plan’s development.

Community Dialogues

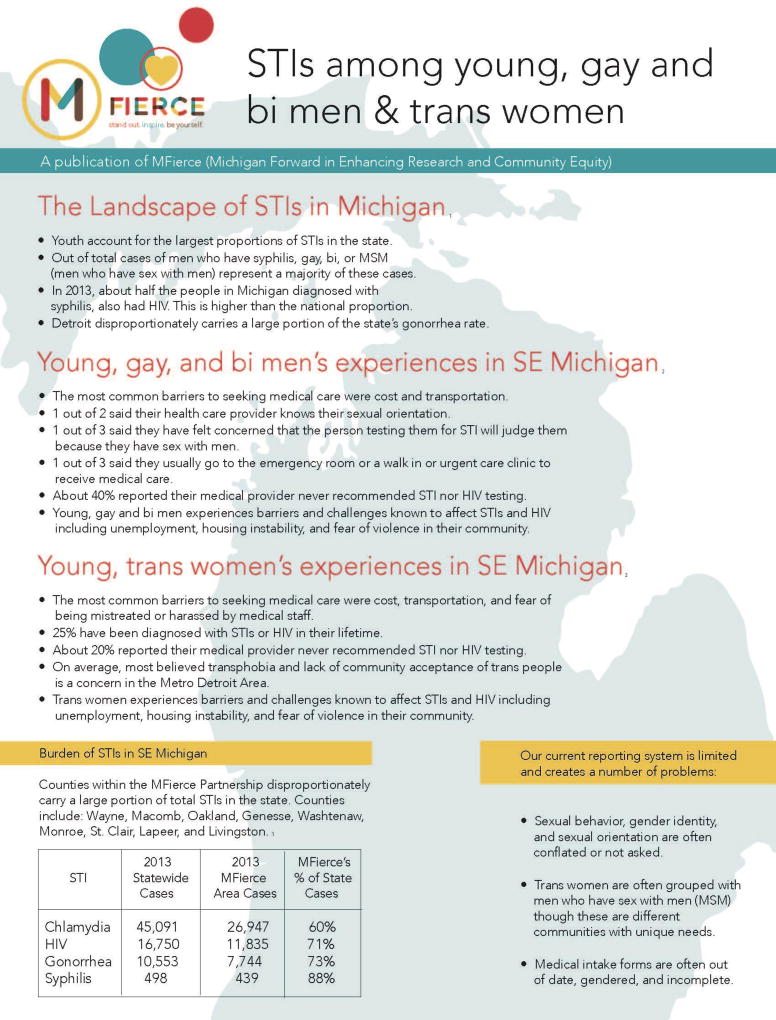

MFierce solicited community input with regard to the primary structural determinants of STI rates among YGBMTW in Southeast Michigan early in the process. MFierce hosted an all-day Kickoff Event ten days after the initiation of the project, which was attended by 65 people. Guests were members of more than 45 different agencies around the region, including representatives from county and city health departments, HIV/STI service providers, LGBTQ organizations and youth organizations, and community leaders. The first half of the day was spent presenting the HIV/STI epidemiologic profile of YGBMTW in Southeast Michigan, followed by an introduction to MFierce and two Q&A panels hosted by the YAB and SC. After a luncheon, we divided participants into small groups and asked them to participate in a Force Field exercise for the second half of the day. Typically, groups in a long-term strategic development process use Force Field Analyses. In an abbreviated form, it helped assess the social determinants of health (SDH) that contribute to STIs in local LGBT communities. Kick-Off attendees, who came with either a great deal of knowledge or interest in these issues, were asked by a facilitator to consider the “Forces For” (in support of) and the Forces Against (challenges/obstacles) achieving MFierce’s goal of reducing STI rates among YGMBTW in Southeast Michigan. We provided a handout (see Figure 1) summarizing local data regarding HIV/STI in Southeast Michigan. In light of these identified “forces”, participants were asked to propose three concrete action steps. Afterward, each group reported to the audience as a whole. Participants identified 36 structural forces for and against change in the region and 66 strategies designed to combat or enhance these forces. These identified areas of “Forces For” and “Forces Against” served as the backdrop to the future community dialogues.

Figure 1.

Community dialogue handout illustrating the social determinants of HIV/STI disparities in Southeast Michigan

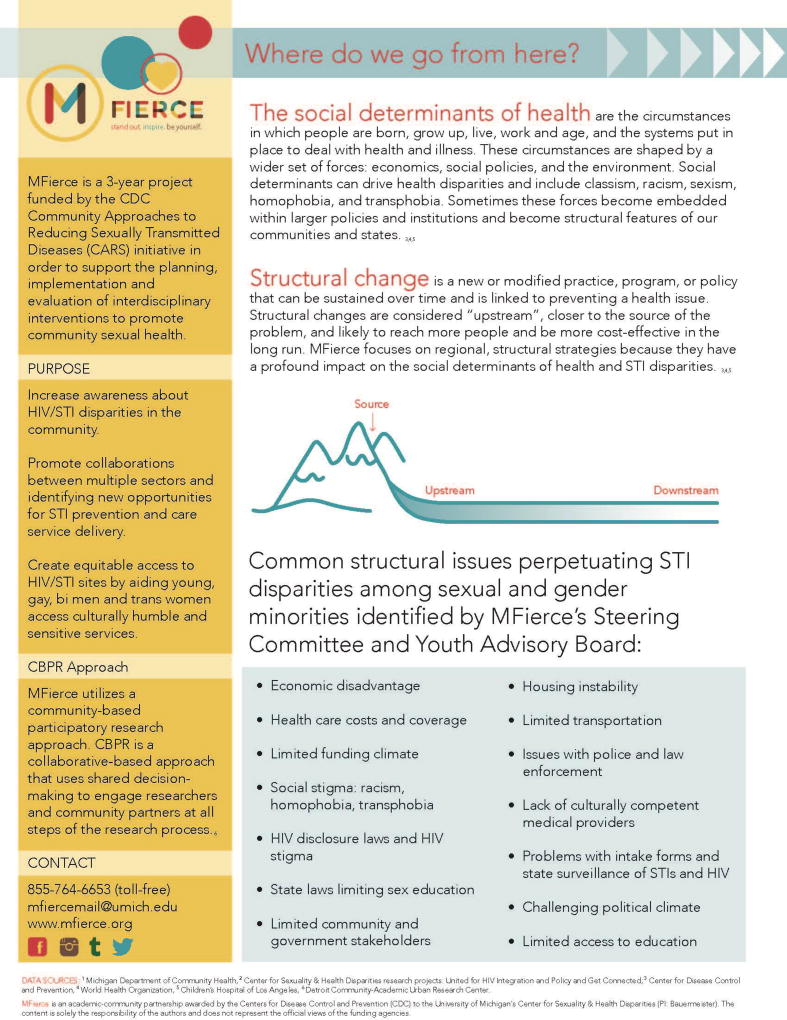

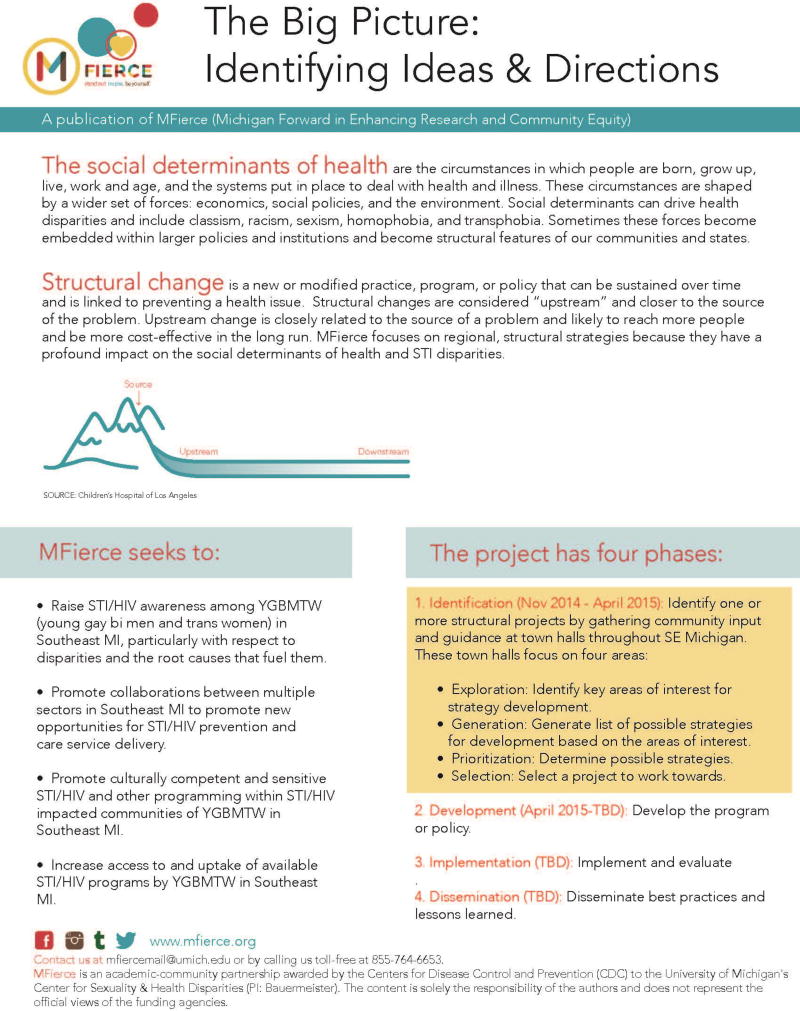

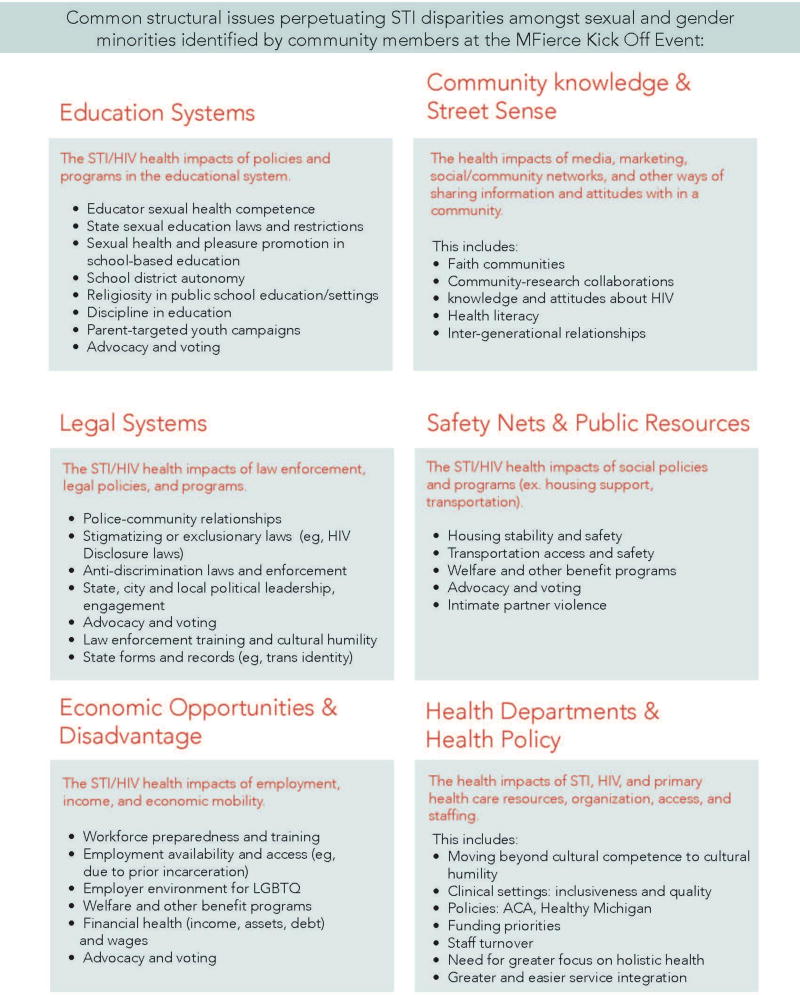

Following the Kickoff, the MFierce coalition met as a whole to discuss the data gathered from the Force Field exercise. Coalition members took turns reading out each of the identified structural forces and the group would then have opportunity for discussion and questions. After each discussion, a facilitator (who was part of the research team) would ask for consensus and then add the identified structural force to an existing thematic cluster or begin a new one. In this way, the coalition began to group similar or related structural factors together. By undertaking this process, the coalition constructed six key domains representing the most urgent and potentially impactful areas of structural change within the context of reducing STI rates: Education Systems, Community Knowledge and Street Sense, Legal Systems, Safety Nets and Public Resources, Economic Opportunities and Disadvantages, and Health Departments and Health Policy. These domains were distilled into an infographic document (see Figure 2 - “Big Picture” Handout), and used in the community dialogues as a frame of reference for attendees.

Figure 2.

Community dialogue handout highlighting structural and community level domains identified during the Kick-Off event

Two conversations unfolded at the Kick-Off that helped shift our focus and language. At our Kick-Off event, our language around the priority population was framed as men who have sex with men (MSM) since this was the original language in our grant. First, younger community members expressed frustration with the term “MSM” because it felt too much like an academic term. Older community members explained that this language came about to shift toward developing programs based on behaviors rather than identity. Consequently, we opted to include both identities and sexual behaviors when referring to our priority population (hence, the focus on YGBMSM). Second, several stakeholders asked MFierce if transgender individuals would be included as a priority population. After discussion, the coalition decided to include transgender women as a priority population. Since explaining the acronym of YGBMTW can be quite wordy, the coalition shifted the language of “the LGBT community” to “LGBT communities” to reflect that there are different communities represented within this project with unique needs.

Community Dialogue Content

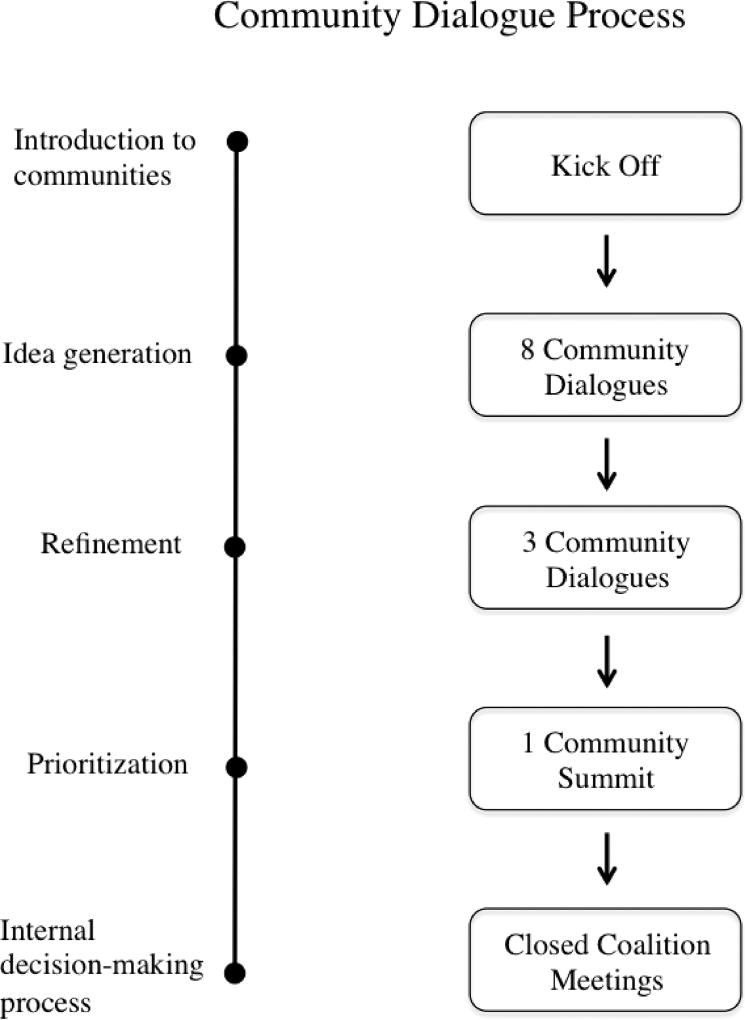

The community dialogues (see Figure 3) were co-facilitated by the YAB, SC, and SL teams. As we developed the content of these community dialogues, we employed a three-round process to synthesize the ideas of our program plan into actionable strategies. Below, we describe the three rounds of community dialogue and highlight their importance for our program planning process.

Figure 3.

Summary of our Community Dialogue Process

Round 1 - Idea Generation

For the initial round of community dialogues, the MFierce coalition as whole (i.e., the YAB, SC, and SL) decided to have two facilitators at each event: a YAB facilitator and a SL or SC facilitator.

Since the YAB members had varying degrees of experience with facilitation, a professional facilitator not affiliated with MFierce offered a training for the YAB two weeks prior to the first community dialogue. In addition, SL team members collaborated with YAB members with the goal of familiarizing everyone with the facilitation guide to be used throughout each community dialogue. Overall, the facilitation guide consisted of scripts offering instructions for each of the activities to be completed in the course of the community dialogue, including idea generation on index cards, small group discussions, and coordinated categorization of ideas into the six key domains mentioned above. The original guide was deemed too dense and lengthy by YAB members. The SL team therefore worked with the YAB to revise and simplify the guide prior to the first dialogue and after subsequent dialogues.

The structure of the first round of community dialogues (N=8) involved introductions, explanations of the project, and an icebreaker followed by a discussion of the six domains (see Figure 1). Participants were asked to offer examples of immediate or long-term goals for change in each of the six domains and then to talk about how such a change would reduce HIV/STI outcomes in their community. For example, in the health domain, a participant might suggest “increased STI testing” as a goal and then explain to the group how such an increase would reduce rates over time. After this clarifying discussion, participants were assigned a domain and asked to write down as many goals as possible within five minutes, with each goal being written on a separate index card. All of these goals were then shared with the larger group and placed on a sticky board at the front of the room. After a short break, participants then got together with others who had worked on their same domain (e.g., those who had generated goals related to education sat at a table together) and as a group, devised strategies that the coalition might implement in order to achieve at least several of the goals within their domain (e.g., given the goal of higher GED completion rates, a group might suggest the strategy of offering more GED classes at the local library). The goals were often broad and potentially vague; the strategies were meant to offer concrete ideas to the coalition about ways in which to move forward. Each community dialogue ended with a debriefing session and time allotted to complete the evaluation. Participants were invited to attend future dialogues, spread the word to others that might be interested, and connect with the project via social media.

Round 2 – Refinement

Between Rounds 1 and 2, the entire coalition organized a retreat at which the ideas generated in Round 1 were discussed and prioritized. SC, YAB and SL team members identified their top choices for project directions in Year 2 within each domain, based on considerations of the feasibility, acceptability, and desirability of each idea. This process resulted in a list of 12 potential intervention areas for reducing HIV/STI rates among YGBMTW in the region. In Round 2 of the community dialogues (N=3), two SL team members briefly explained each of the 12 intervention areas, followed by an open discussion with participants. Subsequently, participants were given three stickers – one red, one yellow and one green – with which they voted on their top 3 choices (green = 1st choice; red = 3rd choice). The intervention areas that received the most votes (3 to 4 areas out of 12) were announced. Participants then split up into 3–4 groups and each group was given nearly an hour to create their own design for an intervention in their area. The facilitators provided each group with a “project mapping” worksheet that served as a guide. It included boxes in which participants detailed what the project would require in terms of resources, materials, and personnel, the primary activities comprised by the project, and the anticipated impact upon HIV/STI rates among YGBMTW in Southeast Michigan. Each group presented their idea at the end and had the opportunity to field questions.

Round 3 – Prioritization

The final round of community dialogues was a single culminating event that the coalition dubbed the Summit. Using the project maps from Round 2, coalition members met in the interim, sketched in further details for each proposal, and consolidated several of the ideas where overlaps occurred. The day of the Summit, the coalition presented seven final ideas, utilizing a roundtable format. A team of coalition members that included at least one SC member, one YAB member, and one SL member managed each of seven tables. Summit participants were assigned to a group (that was presented on their nametag upon entry) and their group would spend 15 minutes at each of the tables, gradually making their way around over a two-hour period. At each roundtable session, the coalition members representing the table would introduce their proposal, communicate key points regarding the significance and impact of the work, and elucidate five specific activities to be implemented in service of the project. Participants then had the opportunity to voice concerns or questions. After visiting all seven tables, everyone was treated to lunch and requested to vote on which proposal they perceived to have the greatest impact, feasibility, and need.

Recruitment

We recruited people to attend our community dialogues using a variety of methods. First, we designed a colorful and informative advertisement for the town hall events, which was used as a digital flyer and a printed palm card. The palm cards/flyers described the purpose of the MFierce community dialogues, offered information on dates, times and locations, and mentioned that food would be served and a travel stipend of $15 available for attendees. We varied the color palette of these flyers per event to reduce the likelihood of confusing different days/times. In addition, the YAB maintained a substantial social media presence via Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Tumblr, which they used to promote the community dialogues. SC and SL teams used their Facebook pages, websites, and email networks to invite stakeholders to the events. Beyond our personal and professional networks, we also distributed printed palm cards to dozens of local agencies and at social events for the LGBT community in the region. Further, we posted ads on several local online news sources. Participants who attended Round 1 of our community dialogues were also reminded of subsequent events (e.g., Rounds 2 and 3) so they could continue to participate in the decision-making process. Organizations, agencies, and providers were specifically recruited for Round 2 and Round 3, although the events were open to all interested individuals and organizations.

As MFierce began to prepare the community dialogues, the YAB expressed the importance of hosting youth-only and transgender-only meetings. The youth-only meetings would give people aged 30 or under a chance to participate in an open space without being intimidated or silenced by older community members and/or professionals. Similarly, the transgender-only space would provide safety and comfort to transgender individuals whose contributions have a history of being silenced in LGBT community spaces. In addition to these meetings, we also considered how to distribute the community dialogues across Southeast Michigan to avoid constraining attendance to these events, as our catchment area encompasses a large geographic space covering over six counties with limited public transportation options between them. As a collective, we considered how to ensure geographical diversity while balancing limited time and resources. Therefore, of the 12 community dialogues that were implemented over two and a half months, we had nine town halls in prominent cities in our region (e.g., Detroit, Flint, and Ann Arbor) so as to not overtax our resources. We also offered three town halls in adjacent cities to ensure diversity in constituents, as SC members noted that the three major city centers are most often heard from when regional initiatives are planned. Two community dialogues were youth-only and two were transgender-centric. We varied the time of day, the day of the week, and the venue types (e.g., library, university space, community organization space) in order to give as many people as possible an opportunity to attend and participate.

Recruitment activities varied over time and included general and targeted outreach: email listservs, social media, word of mouth, flyers and palm cards, announcements at meetings, newspaper ads, and personalized emails and phone calls. Outreach for YGBMSM and transgender youth required specific, targeted outreach with an emphasis on social media and reliance of existing personal connections. While numerous strategies were used to recruit participants, two scheduled town halls had no participants. Both of these town halls were for specific sub-populations (one for youth, and another for transgender youth). On the other hand, personal emails were particularly useful for our three town halls in Round Two since we were specifically trying to recruit providers, program staff, and people with expertise in intervention development and implementation.

Evaluation

At the end of each community dialogue, participants were asked to complete an evaluation form. A member of the research team distributed and collected the forms at the end of each community dialogue; however, participants who needed to leave early were also encouraged to complete the evaluation form before leaving. The evaluation form began with seven demographic questions including age, race/ethnicity, sexual identity, and gender identity/expression. We used 11 items to ascertain participants’ opinions regarding the facilitation, objectives, mood, and logistics of the community dialogue. These items were rated on a four-point Likert scale (1=Strongly Disagree; 4=Strongly Agree; see Table 1). We computed the mean and standard deviation for each item in our evaluation assessment, both as an overall metric of satisfaction as well as by type of community dialogue.

Table 1.

Evaluation data from Community Dialogues (N=173)

| Round 1 (N=87) M(SD) |

Round 2 (N=40) M(SD) |

Round 3 (N=46) M(SD) |

Total (N=173) M(SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I understood the objectives of today’s meeting. | 3.62(.58) | 3.62(.54) | 3.65(.48) | 3.63(.54) |

| The facilitators always provided clear instructions. | 3.54(.64) | 3.73(.45) | 3.61(.49) | 3.60(.57) |

| The facilitators were responsive to the audience questions. | 3.71(.55) | 3.77(.48) | 3.64(.47) | 3.72(.51) |

| The facilitators seemed knowledgeable. | 3.64(.57) | 3.83(.45) | 3.67(.47) | 3.69(.52) |

| The activities were useful for my learning. | 3.64(.57) | 3.62(.54) | 3.59(.50) | 3.62(.55) |

| I felt that my voice was heard. | 3.70(.59) | 3.70(.46) | 3.61(.54) | 3.68(.55) |

| I felt comfortable participating. | 3.66(.54) | 3.75(.44) | 3.61(.58) | 3.67(.53) |

| The time of the meeting was convenient for me. | 3.59(.62) | 3.52(.60) | 3.46(.66) | 3.54(.62) |

| The location of the meeting was convenient for me. | 3.48(.73) | 3.65(.62) | 3.54(.59) | 3.54(.67) |

| This event was useful for increasing my knowledge around important issues. | 3.62(.65) | 3.52(.64) | 3.57(.58) | 3.58(.63) |

| This event will benefit the communities that I care about. | 3.74(.54) | 3.77(.43) | 3.70(.47) | 3.73(.49) |

Notes. Items are rated on a 4-point scale (1=Strongly Disagree; 4=Strongly Agree).

Over the course of all three rounds of town halls, 173 evaluation forms were completed. The average age overall was 32 years old (SD=12). The median age was 28. The proportion of participants who represented the age group of interest (ages 15–29) was 66.3%. Overall, the proportion of participants who identified as Black or African American was 55.2%, as Latino or Hispanic was 6.4%, and as White was 33.1%. The remaining participants (5.3%) identified as one of the following: Middle Eastern or Arab, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, Irish, Mixed, Multi-facial, Multiracial, or Biracial.

We also had a diverse representation of sexual and gender identities. The majority of participants identified as Gay, Lesbian or Homosexual (55.5%), followed by Straight or Heterosexual (27.7%), and Bisexual (5.8%). The remaining participants (11.0%) identified their sexual identity as one of the following: Pan or Pansexual, Queer, Trans or Transgender, and Free. With regard to gender identity, the proportion of participants who were assigned the sex of Male at birth was 62.0% and who were assigned the sex of Female at birth was 37.4%. The remaining participants (0.6%) identified as Free. Participants identified their current gender as Male (52.6%), Female (36.8%), or Transgender Female (6.4%). The remaining participants (4.7%) identified as Woman Thing, Agender, or Man/Woman. Given that the MFierce partnership seeks to reduce STIs among YGBMTW between the ages of 15 and 29, we also examined what proportion of our participants represented these sexual/gender identities. Over half of attendees (56.7%) were from the populations of interest.

Round One of the community dialogue had the greatest number of evaluation forms completed (n=87) given the number of meetings dedicated to brainstorming ideas across the six domains. Round Two, which focused on project mapping, had 40 evaluation forms completed. 71.8% of participants in Round 2 had previously attended an MFierce event, 25.6% had not, and 2.6% were unsure. Round Three had 46 evaluation forms completed, with 79.5% of participants reporting having previously attended an MFierce event. As noted in Table 1, participants noted high satisfaction across the three rounds of community dialogues with regard to the purpose and importance of the events, the activities and facilitation at each round, and their perceived comfort and participation in the community dialogue process. The median score for evaluation items across each round was four. We also examined whether there were differences in satisfaction scores between events within each round, and found no differences in participants’ ratings.

Selecting the intervention activities

After the community dialogues had concluded, MFierce held several all-coalition, in-person meetings to decide which strategies to adopt based on the data and information from this iterative process. We are currently implementing two major initiatives: Health Access Initiative (HAI) and the Advocacy Collective (AC). HAI seeks to offer healthcare providers across Southeast Michigan with cultural humility training focused on YGBMTW, whereas the AC is a training program for YGBMTW that prepares them for consulting roles vis-à-vis organizations looking to offer or expand programming for LGBTQ youth.

DISCUSSION

Community organizing is a central approach to addressing HIV/STI disparities, as outlined in the United States National HIV/AIDS Strategy. In accordance with these efforts, we sought to describe the community organizing process that we employed in Southeast Michigan during the program planning phase of a new structural initiative to reduce HIV/STIs among YGBMTW. The inclusion and participation of constituents and stakeholders during the development of community programs ensures that diverse perspectives are included during the decision-making process. Our community dialogues brought in the perspectives of key stakeholders and integrated them into MFierce’s subsequent intervention activities. Our three-round process created opportunities for community members to participate and share in the program-planning decision-making process. Constituents and stakeholders juxtaposed prior programmatic successes and failures with emergent ideas stemming from the community dialogues. These conversations offered insights into the feasibility, acceptability, and sustainability of the different ideas proposed. In addition, the overall process has allowed the coalition to solicit buy-in from potential partners and made it easier to call upon these relationships as we begin to implement our interventions.

Lessons Learned

During the course of this community organizing process, we learned several valuable lessons. The challenges and triumphs that occurred while the coalition was working toward a common goal of developing a structural initiative geared to reduce HIV/STIs among YGBMTW in Southeast Michigan informed the development of “best practices” that have generalizability to other coalitions. Although various elements of these recommendations are detailed throughout this paper, several core principles have guided the development and implementation of our collaborative community-centered process. First, we sought to adhere to cultural humility principles (Tervalon, M. & Murray-Garcia), recognizing that community input and expertise was as valuable as public health and/or empirical data during the program planning process. For example, we learned that being humble to community input on language used to define the key populations of interest (e.g., gay vs. “men who have sex with men”) was crucial as we aligned the programmatic strategies. Younger community participants highlighted that the proposed strategies should refer to key populations based on sexual and gender identity (e.g., gay, bisexual, queer, transgender) descriptors rather than on epidemiologic jargon (e.g., men who have sex with men) used to describe the route of HIV/STI infection. Community members highlighted how a focus on body parts or sexual behaviors diminished our ability to consider strategies focused on their sociocultural environments. Given the history of mistrust with research institutions in public health and medicine, listening to and incorporating community member’s feedback into our program planning process helped build trust and relationships with members of marginalized communities or organizations that serve them. These challenges often served to remind us of the necessity of revisiting our shared values as a coalition, thereby invigorating our work on behalf of the project.

One of the greatest priorities for our community dialogues was ensuring an adequate number and diversity of voices in the room. Thus, we learned that engaging community members and organizations early and often in the program planning process helped build support for our programs. Co-facilitation during the community dialogues was a powerful tool to make youth perspectives as visible as the opinions of coalition researchers and service providers. Undoubtedly, co-facilitation allowed for diverse representation during the community dialogues and for diverse ideas to be expressed and discussed. Co-facilitation was an iterative learning process through which we learned to be conscious about when to speed up versus when to slow down, when to listen versus when to talk, when to sit with discomfort versus when to build cohesion, when to deliberate versus when to act. Although ultimately rewarding, efforts to coordinate the trainings and the scheduling of co-facilitated dialogues surpassed our original expectations regarding the time and resources that would be required. Allocating sufficient time and resources to these efforts is paramount given challenges when coordinating competing calendars, schedules and community events, as well as identifying, reserving, and promoting the community dialogues in public and accessible spaces.

Third, community engagement activities should be varied is size and scope. Attendance at community dialogues varied, from six to sixty-five participants. Numerous strategies were used to allow diverse participation, including varying the time and location of events. We focused on both general and targeted outreach channels (e.g., listservs, social media, word of mouth, flyers and palm cards, announcements at meetings, newspaper ads, and personalized emails and phone calls). Outreach efforts were triangulated with the focus of each round of community dialogues. For example, general channels were effective for representation of diverse constituents and stakeholders during the Kick-Off and Community Summit. Personalized emails and invitations were particularly useful in the three community dialogues of Round Two since we were specifically trying to recruit providers, program staff, and people with expertise in intervention development and implementation. Conversely, community dialogues designed for specific sub-populations (e.g., youth and transgender youth) required broader outreach with an emphasis on targeted social media and existing personal connections. In general, the more time and energy expended by coalition members to ensure dialogue attendance (e.g., making phone calls, distributing advertisements, sending out individualized invitations, and establishing convenient times/places), the greater the attendance.

Finally, the community dialogue process help clarify roles during internal decision-making processes. We held several all-coalition, in-person meetings in the weeks following the last community dialogue to decide which strategies to formally adopt. In reflecting on these, we came to understand that the voting process at the last community dialogue (Community Summit) reflected the roles and strengths associated with our coalition’s membership. During the decision-making process, the role of the academic team was to understand and communicate practice research, which interventions could be most impactful based on empirical evidence, and what programmatic attributes could lead to successful and sustainable projects. The role of the steering committee was to focus on the community practice perspective, consider policy and environmental resources and challenges, and explain what would be most feasible given time and resource constraints. The youth advisory board’s role focused on communicating and clarifying what was most needed, often reminding the coalition of struggles that might be invisible to or not prioritized by agencies and researchers.

CONCLUSIONS

Building and sustaining of interpersonal relationships between coalition members and community stakeholders is crucial throughout the program planning process. To be effective, the community dialogues required persistence and effortful coordination among many individuals. Mutual respect, patience, and openness among coalition members was crucial, in addition to thoughtful engagement between facilitators and dialogue participants. Continued efforts to mitigate the HIV/STI burden among sexual and gender minority youth through community-relevant program planning strategies are warranted, and will require the full capacity of community-academic expertise to implement the most effective solutions. Additional examples of community engagement practices used by other community groups and coalitions may serve to create a comprehensive resource that supports ongoing public health efforts. Through a description of our community dialogue process, with its attendant struggles and successes, we contribute evidence to the possibilities inherent in a community organizing approach to advancing the health and wellbeing of YGBMTW.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U22PS004520-01; PI: Bauermeister). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the funding agency.

Contributor Information

José A. Bauermeister, University of Pennsylvania.

Emily S. Pingel, Emory University.

Triana Kazaleh Sirdenis, University of Michigan.

Jack Andrzejewski, University of Michigan.

Gage Gillard, University of Michigan.

Gary W. Harper, University of Michigan.

References

- Alcantara L, Harper GW, Keys C. “There’s gotta be some give and take”: Community partner perspectives on benefits and contributions associated with community partnerships for youth. Youth and Society. 2015;47(4):462–485. doi: 10.1177/0044118X12468141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Connochie D, Eaton L, Demers M, Stephenson R. Geospatial indicators of space and place: A review of multilevel studies of HIV prevention and care outcomes among young men who have sex with men in the United States. Journal of Sex Research. 2017 doi: 10.1080/00224499.2016.1271862. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Pingel ES, Jadwin-Cakmak L, Meanley S, Alapati D, Moore M, Lowther M, Wade R, Harper GW. The use of mystery shopping for quality assurance evaluations of HIV/STI testing sites offering services to young gay and bisexual men. AIDS & Behavior. 2015;19(10):1919–1927. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1174-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauermeister JA, Goldenberg TS, Connochie D, Jadwin-Cakmak L, Stephenson R. Psychosocial disparities among racial/ethnic minority transgender young adults and young men who have sex with men living in Detroit. Transgender Health. 2016;1:279–290. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2016.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce D, Harper GW, Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions Operating without a safety net: Gay male adolescents’ responses to marginalization and migration and implications for theory of syndemic production for health disparities. Health Education and Behavior. 2011;38(4):367–378. doi: 10.1177/1090198110375911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doll M, Harper GW, Robles-Schrader G, Johnson J, Bangi AK, Velagaleti S, the ATN Perspectives of community partners and researchers about factors impacting coalition functioning over time. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 2012;40:87–102. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2012.660120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellen JM, Greenberg L, Willard N, Korelitz J, Kapogiannis BG, Monte D, Boyer CB, Harper GW, Henry-Reid LM, Friedman LB, Gonin R. Evaluation of the impact of HIV-related structural interventions: The Connect to Protect Project. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169(3):256–263. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eng E, Blanchard L. Action-oriented community diagnosis: A health education tool. International Quarterly of Community Health Education. 2006;26(2):141–158. doi: 10.2190/8046-2641-7HN3-5637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo R, Ozmer E, Sullivan C, Doll M, Harper G. Environmental, psychosocial, and individual correlates of HIV risk in ethnic minority male-to-female transgender youth. Journal of HIV/AIDS Prevention in Children & Youth. 2007;7(2):89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW. Sex isn’t that simple: Culture and context in HIV prevention interventions for gay and bisexual male adolescents. American Psychologist. 2007;62(8):803–819. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.62.8.806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Bangi AK, Contreras R, Pedraza A, Tolliver M, Vess L. Diverse phases of collaboration: Working together to improve community-based HIV interventions for youth. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;33(3/4):193–204. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000027005.03280.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Willard N, Ellen J, Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions Connect to Protect®: Utilizing community mobilization and structural change to prevent HIV infection among youth. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 2012;40:81–86. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2012.660119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel B, Coombe C, Cheezum R, Schulz A, McGranaghan R, Lichtenstein R, Reyes A, Clement J, Burris A. Community-based participatory research: A capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100(11):2094–2102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamil OB, Harper GW, Fernandez MI, Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions Sexual and ethnic identity development among gay/bisexual/questioning (GBQ) male ethnic minority adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2009;15(3):203–214. doi: 10.1037/a0014795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz P, Viruell-Fuentes E, Israel B, Softley D, Guzman R. Can communities and academic work together on public health research? Evaluation results from a community-based participatory research partnership in Detroit. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78(3):495–507. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RL, Janulis PF, Reed SJ, Harper GW, Ellen J, Boyer CB, Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions Creating youth-supportive communities: Outcomes from the Connect-to-Protect® (C2P) structural change approach to youth HIV prevention. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2016;45(2):301–315. doi: 10.1007/s10964-015-0379-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Community organizing and community building for health and welfare. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pingel ES, Thomas L, Harmell C, Bauermeister JA. Creating comprehensive, youth centered, culturally appropriate sex education: What do young gay, bisexual, and questioning men want? Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2013;10(4):293–301. doi: 10.1007/s13178-013-0134-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes S. Innovations in HIV prevention research and practice through community engagement. New York: Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Robles-Schrader GM, Harper GW, Purnell M, Monares V, the ATN Differential challenges in coalition building among HIV prevention coalitions targeting specific youth populations. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 2012;40:131–148. doi: 10.1080/10852352.2012.660124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Balcazar Y, Harper GW. Community-based approaches to empowerment and participatory evaluation. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 2003;26(2):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Balcazar Y, Harper GW, Lewis R. An interactive and contextual model of community-university collaborations for research and action. Health Education and Behavior. 2005;32(1):84–101. doi: 10.1177/1090198104269512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner A, Philbin M, Duval A, Ellen J, Kapogiannis B, Fortenberry JD. The adolescent trials network for HIV/AIDS interventions. “Youth friendly” clinics: considerations for linking and engaging HIV-infected adolescents into care. AIDS Care. 2014;26:199–205. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2013.808800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 1998;9(2):117–125. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson BDM, Harper G. Race and ethnicity in lesbian, gay and bisexual communities. In: Patterson CJ, D’Augelli AR, editors. Handbook of Psychology and Sexual Orientation. New York: Oxford University Press; 2013. pp. 281–296. [Google Scholar]

- Ziff MA, Harper GW, Chutuape KS, Deeds BG, Futterman D, Francisco VT, Ellen JM, the Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Intervention Laying the foundation for Connect to Protect®: A multi-site community mobilization intervention to reduce HIV/AIDS incidence and prevalence among urban youth. Journal of Urban Health. 2006;83(3):506–522. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9036-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziff MA, Willard N, Harper GW, Bangi AK, Johnson J, Ellen JM. Connect to Protect® researcher-community partnerships: Assessing change in successful collaboration factors over time. Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice. 2010;1(1):32–39. doi: 10.7728/0101201004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]