Neutrophil granule release is dysregulated in patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis (ALD) with augmented effector organelle mobilization and microbiocidal protein release. Neutrophil granules are upregulated in ALD at baseline and demonstrate augmented responses to bacterial challenge. The granular responses in ALD did not contribute to the observed functional deficit in innate immunity but rather were dysregulated and hyperresponsive, which may induce bystander damage to host tissue. Paradoxically, active alcohol consumption abrogated the excessive neutrophil granular responses to bacterial stimulus compared with their abstinent counterparts.

Keywords: alcohol-related cirrhosis, neutrophil, degranulation

Abstract

Patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis (ALD) are prone to infection. Circulating neutrophils in ALD are dysfunctional and predict development of sepsis, organ dysfunction, and survival. Neutrophil granules are important effector organelles containing a toxic array of microbicidal proteins, whose controlled release is required to kill microorganisms while minimizing inflammation and damage to host tissue. We investigated the role of these granular responses in contributing to immune disarray in ALD. Neutrophil granular content and mobilization were measured by flow cytometric quantitation of cell-surface/intracellular markers, [secretory vesicles (CD11b), secondary granules (CD66b), and primary granules (CD63; myeloperoxidase)] before and after bacterial stimulation in 29 patients with ALD cirrhosis (15 abstinent; 14 actively drinking) compared with healthy controls (HC). ImageStream Flow Cytometry characterized localization of granule subsets within the intracellular and cell-surface compartments. The plasma cytokine environment was analyzed using ELISA/cytokine bead array. Circulating neutrophils were primed in the resting state with upregulated surface expression of CD11b (P = 0.0001) in a cytokine milieu rich in IL-8 (P < 0.001) and lactoferrin (P = 0.035). Neutrophils showed exaggerated mobilization to the cell surface of primary granules at baseline (P = 0.001) and in response to N-formyl-l-methionyl-l-leucyl-l-phenylalanine (P = 0.009) and Escherichia coli (P = 0.0003) in ALD. There was no deficit in granule content or mobilization to the cell membrane in any granule subset observed. Paradoxically, active alcohol consumption abrogated the hyperresponsive neutrophil granular responses compared with their abstinent counterparts. Neutrophils are preprimed at baseline with augmented effector organelle mobilization in response to bacterial stimulation; neutrophil degranulation is not a mechanism leading to innate immunoparesis in ALD.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Neutrophil granule release is dysregulated in patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis (ALD) with augmented effector organelle mobilization and microbiocidal protein release. Neutrophil granules are upregulated in ALD at baseline and demonstrate augmented responses to bacterial challenge. The granular responses in ALD did not contribute to the observed functional deficit in innate immunity but rather were dysregulated and hyperresponsive, which may induce bystander damage to host tissue. Paradoxically, active alcohol consumption abrogated the excessive neutrophil granular responses to bacterial stimulus compared with their abstinent counterparts.

the incidence and prevalence of cirrhosis are fast increasing, and cirrhosis is now the fifth most common cause of death in the United Kingdom with mortality rates predicted to double within 20 years (10). Susceptibility to infection remains one of the main concerns in patients with cirrhosis with a variety of components of the innate immune system reported to be dysfunctional. Bacterial infection is demonstrable in 34–44% of patients admitted to hospital (8, 18), and the risk of infection correlates with the severity of cirrhosis (11). Infections frequently precipitate decompenzation and multiple organ failure (MOF) and are associated with a high mortality rate; infections increase mortality more than threefold in cirrhosis and confer a damning prognosis, with 30% of patients dying in the first month after infection and 60% after 1 year (5, 17).

Neutrophils are key players in the innate immune system providing the first line of defense against bacterial infection and constitute 40–60% of the white blood cell population. Neutrophils travel in a resting state in the healthy adult circulation with their microbicidal proteins stored intracellularly in granules and with low levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated in the resting state (7). A number of abnormalities in neutrophil physiology have been reported in the context of cirrhosis; neutrophils have been shown to have impaired chemotaxis (12, 15, 20), opsonization (26, 35), phagocytosis (19, 30), and elevated spontaneous ROS production (27). Furthermore, the degree of neutrophil dysfunction observed in patients with cirrhosis has been shown to be predictive of the risk of infection, organ failure and mortality (34). Neutrophil dysfunction in cirrhosis has been shown to be reversible with ex vivo removal of endotoxin from patient plasma reducing oxidative burst and increasing phagocytic function (25) and normalization of neutrophil cytokine profiles in alcoholic hepatitis after steroid administration (33).

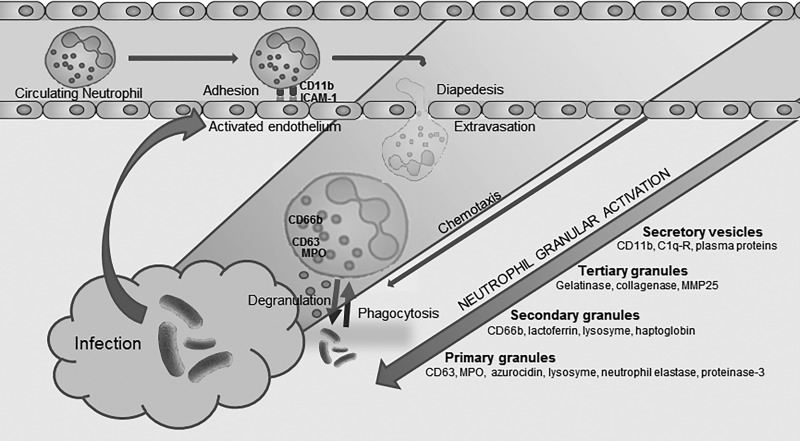

Neutrophil granules are a diverse population of intracellular organelles that develop at sequential stages of myeloid differentiation and contain a specific milieu of proteins (representative of the evolving cellular transcriptome) with targeted functions. Neutrophil granules are mobilized and released at the cell surface and in the endo-phagosome in ordered sequence throughout neutrophil activation (6). Granule release is necessary for adhesion, diapedesis, chemotaxis, and the eventual release of potent microbicidal peptides at sites of inflammation and infection. This ordered and controlled sequence serves to minimise bystander damage to host tissue in healthy states (31) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Graphic representation of neutrophil function, demonstrating conversion from a circulating inactive immune cell to targeted degranulation and phagocytosis at sites of inflammation. The process occurs via sequential control of neutrophil granules which contain specific arrays of proteins that serve specific and timely functions relating to neutrophil activation (7). Initial interaction occurs with the vascular endothelium via selectins and cell adhesion molecules which facilitate rolling, adhesion and subsequently diapedesis across the endothelial membrane into the interstitial space. This in turn allows hierarchical activation of the neutrophil with mobilization of granules to the cell surface and release of chemokines, cytokines, and microbicidal proteins in a time-ordered sequence, allowing the neutrophil to migrate to areas of inflammation and release microbicidal proteins and reactive oxygen species at targeted areas. MPO, myeloperoxidase.

Secretory vesicles are formed late in neutrophil maturation via endocytosis and contain membrane-bound molecules including CD11b (32) that aid in neutrophil adhesion and migration; these organelles are the easiest granule subtype to mobilize to the cell membrane. Tertiary (gelatinase) granules contain an array of metalloproteinases that are though to aid neutrophil migration within the interstitial tissue but are not interrogated in this study. Secondary (specific) granules are characterized by the presence of lactoferrin (14) and other antimicrobial proteins and have CD66b as a granule marker (16). Secondary granules are released at sites of infection alongside primary granules. CD63 is a lysosomal membrane protein located on neutrophil primary (azurophil) granules (13) and mobilizes to the cell membrane on stimulation where primary granules release their microbicidal contents which include myeloperoxidase (MPO) (28).

Data so far on the role of neutrophil granules in innate immune function in the context of cirrhosis are sparse and contradictory with studies demonstrating both normal degranulation patterns and impaired granule release upon response to bacterial stimulation (22, 30). Neutrophils have been shown to have reduced MPO release in response to bacterial peptide stimulation in the context of ALD in addition to reduced cell surface CD11b expression (9, 24). Further characterization of this immunological deficit, crucial to innate immune system function, will enhance understanding of one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in liver disease and potentially elucidate therapeutic targets.

We hypothesized that either a quantitative deficit in neutrophil granular content exists or that there is an impairment of response to bacterial stimulation in terms of mobilization of granule content and extracellular release; these factors contributing to the observed increased risk of bacterial infection in cirrhosis. The aim of this study was to characterize neutrophil granule mobilization and release in patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis (ALD cirrhosis) compared with healthy controls (HC) to further delineate mechanisms of innate immune system compromise in ALD patients and identify potential therapeutic targets for intervention.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

Twenty-nine patients with ALD cirrhosis were recruited including 15 actively drinking and 14 abstinent and compared with HC (n = 12). The patients with ALD cirrhosis were recruited from both outpatient clinics and inpatient wards. A history of excess alcohol intake was defined from thorough clinical history as >80 g/day for men and >60 g/day for women. Abstinence was defined as >6 mo without alcohol consumption. ALD cirrhosis was defined in the presence of either histological criteria, characteristic radiological findings, or typical clinical presentation encompassing the presence of ascites, varices, or encephalopathy. Alcoholic hepatitis was defined clinically with a typical history of excess alcohol intake, biochemical parameters meeting a minimum modified Maddrey’s discriminant function of ≥32 (23), and the absence of other causes of liver disease. Patients were followed longitudinally for 1 yr, and data on subsequent development of sepsis, death, or liver transplantation were recorded.

Inclusion criteria.

Patients with ALD were included if they were >18 and <75 yr and had provided consent for study inclusion. Healthy age- and sex-matched, nonsmoking volunteers with no history of liver disease were used as HC. The HC alcohol intake was <20 g/day, and volunteers did not drink alcohol or exercise excessively in the 72 h before blood was drawn.

Exclusion criteria.

Patients were excluded from the study if, on presentation, they had evidence of bacterial, viral, or fungal infection on the basis of clinical examination, laboratory and radiological investigation, malignancy, and any coexisting history of immunodeficiency, HIV infection, or glycogen storage disease. Patients were also excluded if they were taking any concurrent immunosuppressive medications.

Consent and data collection.

The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical permission was granted from the North East London Research Committee (Ref. No. 08/H0702/52). Following obtaining fully informed consent, clinical, biochemical, and physiological data were collected. Data included tobacco and alcohol use, electrolytes and renal function, liver function tests, differential leukocyte counts, and clotting parameters. Child-Pugh (29) and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) (21) organ severity scores were calculated.

Sample collection.

Venous blood was collected from patients/volunteers into heparinized pyrogen-free tubes and was immediately precooled to 4°C until experimental use. Neutrophil granular phenotype and functional tests were performed within 1 h of blood being drawn. Plasma was obtained by centrifuging whole blood at 4,500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and stored at −80°C for subsequent cytokine determination by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and cytometric bead array.

Characterization of neutrophil extracellular granular phenotype at baseline and after stimulation with bacterial peptides.

One-hundred-microliter aliquots of heparinized blood were placed into pyrogen-free tubes containing 380 µl of Rosenwall Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 media (Sigma-Aldrich). Samples were stimulated with either 20 µl of opsonized Escherichia coli (1.5 × 109 cells/ml) or 20 µl N-formyl-l-methionyl-l-leucyl-l-phenylalanine (fMLP) at 0.2 µM (Becton-Dickenson (BD)] along with control [phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)]. Samples were incubated at 37°C for 20 min, and the reaction was stopped by adding 3 ml of PBS.

The incubated whole blood cell pellet was then stained with fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies [anti-human CD66b IgM κ, anti-human CD63 IgG1 κ, anti-human CD11b IgG1 κ, anti-human myeloperoxidase (MPO) IgG1 κ, and anti-human CD16 IgG1 κ; BD] at room temperature in darkness for 30 min. After being washed and centrifuged, red blood cells were lysed and resuspended in 300 ml PBS and analyzed using a FACS Canto II analyzer and FACS Diva 6.1.2 software (BD). Granulocytes were gated from the cell suspension based on forward and side scatter characteristics and the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD16 was measured. The CD16-positive granulocytes were gated as neutrophils and the MFI of CD11b, CD66b, CD63, and MPO was measured from this cell population.

Characterization of neutrophil intracellular granular phenotype at baseline and after stimulation with bacterial peptides.

Samples were treated as previously described in the incubation and extracellular protocol; however, for the intracellular staining, whole blood was first incubated with anti-CD16 antibody before lysis and fixation and then permeabilization using a cytofix/cytoperm solution (BD). Permeabilized cells were then labeled with fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (anti-human CD66b IgM κ, anti-human CD63 IgG1 κ, anti-human CD11b IgG1 κ, and anti-human MPO IgG1 κ) before being washed, resuspended, and analyzed by FACS.

Cytokine estimation.

Plasma levels of the pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α) were determined from plasma and supernatant samples previously stored at −80°C using cytometric bead array (BD) and results (pg/ml) were correlated with neutrophil granular phenotype, physiological and biological parameters.

Lactoferrin quantification.

Baseline values of lactoferrin, representative of neutrophil secondary granular content, were measured from patient plasma, and incubation medium supernatants were obtained by centrifugation at 4,500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and stored at −80°C. Sandwich ELISA was performed using a Lactoferrin ELISA kit (Merck Millipore).

Image Stream analysis.

Data on the subcellular localization of neutrophil granules was sought by using a similar incubation and fluorochrome-staining protocol for neutrophils from HC and ALD patients utilizing an Image Streamx Mark II Analyzer (Amnis, Seattle, WA), which combines the phenotyping capability of flow cytometry with the detailed imagery and functional insights of microscopy. Comparisons of MFI when gating at the intracellular and cell-surface compartments were made.

Statistical analysis.

Where appropriate, values are expressed as mean, median, and interquartile range. A paired t-test was used for comparisons pre- and poststimulation and Mann-Whitney U-test was used for comparison between two groups. When three or more groups were compared simultaneously, the Kruskal-Wallis was utilized with Dunn’s multiple comparison test. Pearson and Spearman correlations were used for parametric and nonparametric data, respectively. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA); P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient demographics and clinical parameters.

The baseline demographics, biochemical parameters, and disease severity scores of the patients studied are detailed in Table 1. There were trends toward slight increases in markers of liver disease severity and systemic inflammation seen in the actively drinking subset of ALD cirrhosis. In all patients, there was no suspicion of active infection based on clinical evaluation, biochemical, and radiological findings.

Table 1.

Study patient enrolment characteristics, describing age and sex distributions in addition to biochemical and organ severity scores among groups

| Study Group Data | Healthy Controls | Abstinent | Actively Drinking | Total Patient Study Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 12 | 15 | 14 | 29 |

| Age | 34 (31–54) | 54 (45–59) | 53 (47–59) | 54 (47–59) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 6 | 8 | 11 | 19 |

| Female | 6 | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| Bilirubin, µmol/l | — | 40 (30–57) | 123 (56–316)* | 52 (32–141) |

| AST, IU/l | — | 35 (28–58) | 93 (80–138)* | 70 (39–94) |

| ALP, IU/l | — | 123 (93–178) | 153 (133–258) | 140 (106–192) |

| GGT, IU/l | — | 65 (37–109) | 251 (111–503)* | 109 (58–337) |

| Creatinine, µmol/l | — | 88 (62–103) | 58 (43–90) | 68 (52–99) |

| INR | — | 1.53 (1.15–1.91) | 1.56 (1.34–1.81) | 1.53 (1.25–1.83) |

| Albumin, g/l | — | 32 (28–36) | 27 (25–30)* | 29 (26–35) |

| WCC, ×109/l | — | 4.0 (3.4–5.6) | 7.1 (5.7–10.6)* | 5.64 (3.9–7.7) |

| Platelets, ×109/l | — | 110 (67–129) | 130 (110–181) | 123 (92–148) |

| CRP, mg/l | — | 8.7 (5.3–17.7) | 20.2 (11.0–42.1)* | 12.1 (7.3–28.7) |

| Child Pugh score | — | 10 (7–11) | 10 (9–12) | 10 (8–11) |

| MELD score | — | 16 (10–21) | 20 (16–25)* | 18 (13–22) |

| UKELD score | — | 53 (52–58) | 59 (55–62)* | 56 (53–61) |

| Average alcohol intake, g/day | — | 0 | 143 (120–255) | — |

Data are expressed as median and interquartile range. AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; GGT, glutamyl transferase; INR, international normalized ratio; MELD, model for end stage liver disease; UKELD, United Kingdom model for end-stage liver disease. Patients who were actively drinking had trends toward higher markers of liver disease and systemic inflammation.

P < 0.05.

In those with ALD cirrhosis, four (14%) patients developed bacterial infections over the course of 1 yr of follow up with infections equally distributed across abstinent and actively drinking arms. One-year mortality was measured at 14%, with two patients dying from complications of severe sepsis and MOF, one from severe hepatic decompensation and hepatorenal syndrome, and one from unrelated causes. Three abstinent ALD cirrhotic patients were transplanted within 12 mo of enrollment into this study.

Neutrophil granular responses in healthy controls.

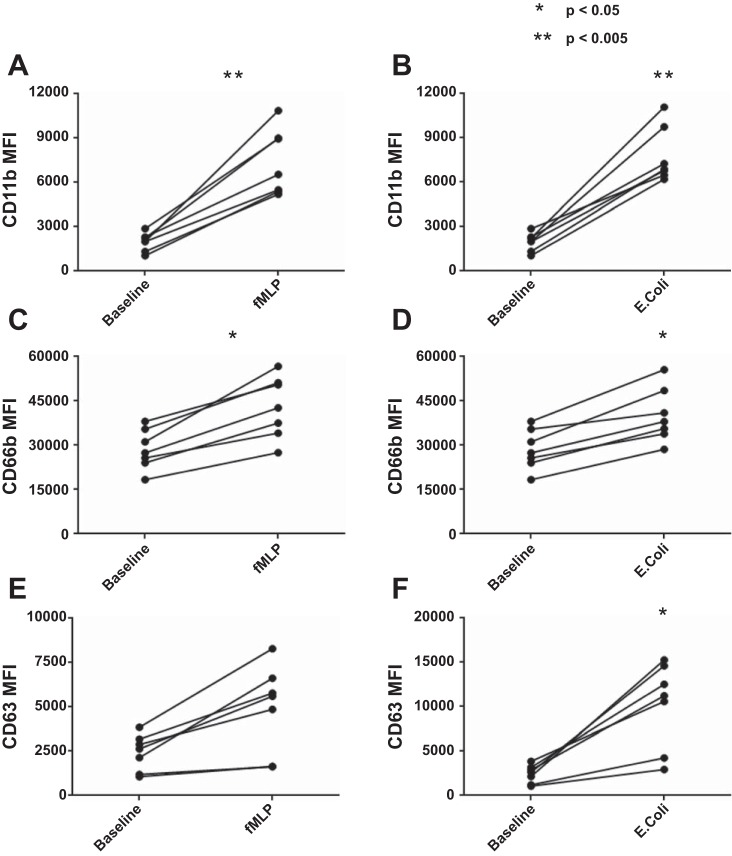

Similar responses to stimulation in healthy controls were seen in both secretory vesicle and secondary granule mobilization to the cell membrane when comparing stimulation with both fMLP and opsonized E. coli (Fig. 2, A–D); however, primary granule responses were significantly elevated after stimulation with E. coli (P = 0.0023) compared with fMLP stimulation (Fig. 2, E and F). A proof of principle Image Stream flow cytometry plot of healthy control neutrophil phenotype demonstrated significant upregulation of CD11b, CD66b, and CD63 at the cell surface in response to stimulation with both fMLP and E. coli in keeping with our FACS Canto flow cytometric data; this was not powered to detect differences between HC and ALD cirrhosis patients (Fig. 3). This is in keeping our understanding of granule physiology with respect to the different levels of calcium-dependent signaling required to mobilize specific granule subsets to the cell membrane (Fig. 1) (3, 7).

Fig. 2.

Extracellular staining in healthy volunteers of fluorochrome-labeled neutrophil granule markers for secretory vesicles (CD11b) (A and B), secondary granules (CD66b) (C and D), and primary granules (CD63) (E and F) pre- and poststimulation with N-formyl-l-methionyl-l-leucyl-l-phenylalanine (fMLP) and opsonized Escherichia coli. Secretory vesicles and secondary granules were similarly significantly upregulated upon stimulation with fMLP, a potent neutrophil chemotaxin, or opsonized E. coli; however, primary granules showed a significantly increased response to bacterial stimulation over fMLP (P = 0.002). MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

Fig. 3.

Image Stream flow cytometry plots of a healthy volunteer demonstrating fluorochrome-labeled staining patterns at the cell surface (A–C) and intracellularly (D–F), at baseline (A and D), after stimulation with the potent neutrophil chemotaxin fMLP (B and E), and after stimulation with opsonised E. coli (C and F). Primary granules (column 1), secondary granules (column 5), and secretory vesicles (column 6) are all upregulated at the cell surface in response to fMLP and E. coli stimulation with a more robust response observed to E.coli. Plots from patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis (ALD) cirrhosis were indistinguishable and did not reveal impaired granule mobilization or localization.

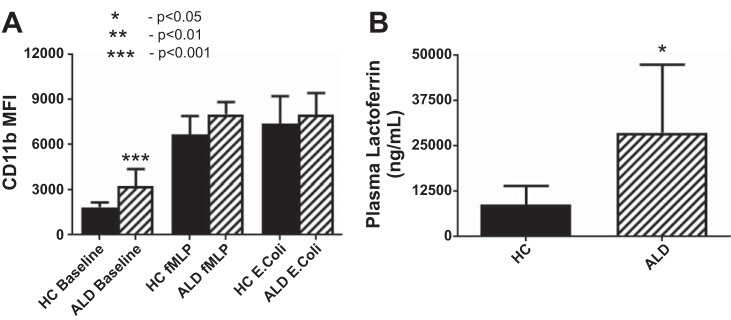

Secretory vesicles.

CD11b, which is expressed in neutrophil secretory vesicles and on the cell surface and binds intercellular adhesion molecule 1 on the activated vascular endothelium to mediate neutrophil binding and initiate the process of extravasation, was significantly elevated in unstimulated neutrophils isolated from ALD patients when measured extracellularly (P = 0.0001; Fig. 4A) and showed a tendency toward upregulation intracellularly. Secretory vesicle mobilization to the cell membrane in response to bacterial stimulation was similar in ALD compared with HC, with no demonstrable deficit in secretory vesicular upregulation at the cell surface in response to bacterial stimulation in ALD cirrhosis.

Fig. 4.

Cell-surface expression of CD11b (A) comparing patients with ALD cirrhosis against HC at baseline, and following stimulation with the neutrophil chemotaxin fMLP and opsonised E. coli. Neutrophils in patients with ALD cirrhosis showed increased expression of CD11b at the cell surface at baseline (P = 0.001) and no impairment of granular mobilization to the cell surface after stimulation with bacterial peptides. There was neither a quantitative secondary granular deficit, nor an impairment of granule mobilization observed in patients with ALD cirrhosis and plasma levels of lactoferrin (B) were increased at baseline when compared with healthy volunteers (P = 0.035), suggestive of increased resting secondary granule release.

Neutrophils examined from patients with ALD cirrhosis were activated at baseline, preprimed to interact with and adhere to the vascular endothelium, and had augmented responses to bacterial stimulation when compared with HC.

Secondary granules.

Secondary granule content and mobilization, as measured by flow cytometric CD66b quantitation on extracellular staining, before and after bacterial stimulation, demonstrated no significant difference in the ALD cirrhosis cohort as compared against HC. Of note, however, there was increased intracellular staining of secondary granules at baseline (P = 0.025) with no impairment in extracellularization of secondary granule content observed in the ALD cohort in keeping with a primed neutrophil phenotype. Baseline plasma levels of lactoferrin were significantly elevated (Fig. 4B) in patients with ALD (P = 0.035) compared with HC suggesting that neutrophils from patients with ALD cirrhosis display augmented secondary granule release in their circulating state.

Primary granules.

CD63 expression was elevated when measured at the cell surface in patients with ALD cirrhosis both at baseline (P = 0.0001) and after stimulation with fMLP (P = 0.009) and E. coli (P = 0.0003) when compared against HC (Fig. 5A). This was matched by intracellular data that showed significant elevations in the intracellular concentrations of primary granules (P = 0.0005) within the neutrophils of patients with ALD compared with HC (Fig. 5B). There was a tendency in ALD cirrhosis toward increased intracellular concentrations of MPO.

Fig. 5.

Cell-surface (A) and intracellular (B) expression of CD63 comparing patients with ALD cirrhosis against healthy volunteers at baseline, and after stimulation with the neutrophil chemotaxin fMLP, and opsonised E. coli. Neutrophils expressed significant upregulation at baseline in primary granule expression both intracellularly (***P = 0.0005) and at the cell surface (**P = 0.001) in patients with ALD cirrhosis compared with healthy volunteers. Neutrophil primary granules were hyperresponsive with significant differences in mobilization to the cell membrane after incubation with fMLP (**P = 0.009) and E. coli (***P = 0.0003).

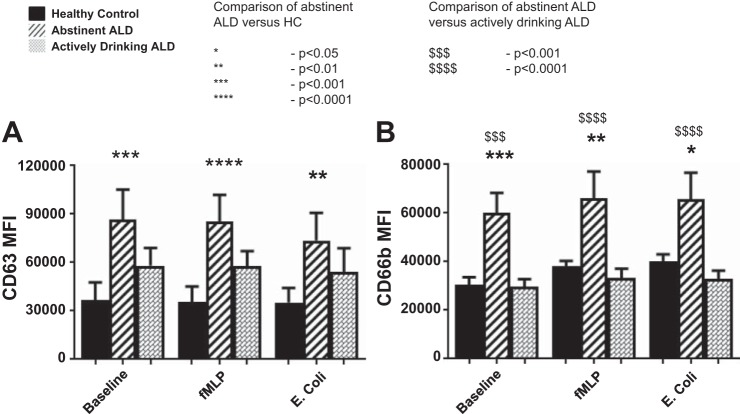

Abstinence vs. active-alcohol consumption in ALD cirrhosis.

When compared with HC, ALD cirrhosis patients who were abstinent had significantly upregulated neutrophil granular function in comparison to HC (CD63 P < 0.001; CD66b P < 0.001); alcohol consumption appeared to abrogate the neutrophil prepriming and exaggerated granular responses in ALD cirrhosis. Dampening of the exuberant neutrophil granular responses and apparent normalization of their activated phenotype in active alcohol consumers were seen in all granule subsets examined (Fig. 6) but were most significantly noted in the intracellular content of primary granules and secondary granules (P < 0.0001).

Fig. 6.

Intracellular expression of primary (A; CD63) and secondary (B; CD66b) granule markers comparing actively drinking patients with ALD cirrhosis against those who had been abstinent for >6 mo and healthy controls (Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s multiple comparison test analysis). Active alcohol consumption normalized the upregulated baseline granule expression and exaggerated response to bacterial stimulation that was seen across all granular subsets. The most significant impact was noted in intracellular staining of primary and secondary granules (P < 0.001).

Neutrophil granular phenotype and severity of liver disease.

There was no observable difference in neutrophil granular phenotype categorized by MELD score; severity of liver disease did not appear to affect neutrophil granular function (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Correlation of extracellular (A, B, and C) and intracellular (D, E, and F) neutrophil granular marker expression at baseline in ALD cirrhosis when compared against model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score. Severity of underlying liver disease did not correlate with changes in neutrophil granular expression at baseline or mobilization in response to bacterial stimulus. ▲: abstinent; ●: actively drinking.

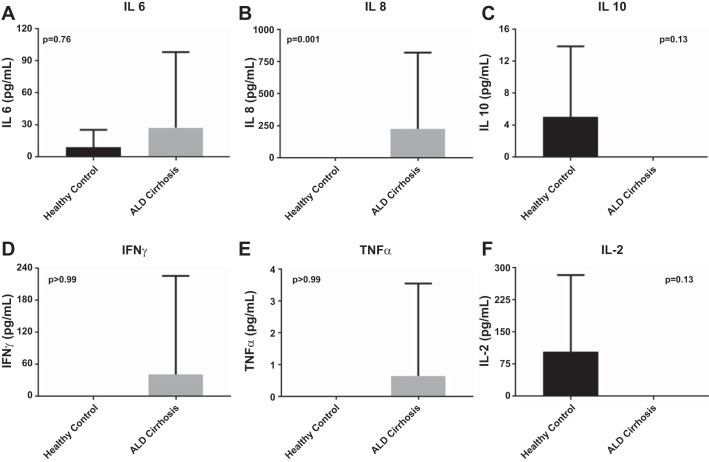

Plasma cytokine levels in ALD cirrhosis.

Plasma from patients with ALD cirrhosis had significantly upregulated levels of IL-8 in comparison to HC (P < 0.001). This is in keeping with the observations of preprimed neutrophil phenotype in a proinflammatory cytokine milieu; there were no significant differences observed in measurements of IFN-γ, IL-10, IL-2, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α; however, trends toward proinflammatory cytokine profiles were seen in ALD (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Supernatant cytokine measurements performed using cytokine bead array demonstrating nonsignificant trends toward upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines [IL-6 (A), IL-8 (B), INFγ (D), and TNFα (E)] in ALD cirrhosis. Conversely, anti-inflammatory cytokines [IL-10 (C) and IL-2 (F)] were downregulated in ALD cirrhosis.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated, contrary to our a priori hypothesis, that neutrophil granular physiology in ALD cirrhosis is neither quantitatively deficient nor is there any demonstrable impairment in granule mobilization and release. Neutrophil granule hyporesponsiveness is therefore unlikely to be contributing to the innate immune paresis observed in ALD cirrhosis. This finding is contradictory to other data with respect to ALD cirrhosis (9, 24); however, this is the first time that individual neutrophil granular subsets have been described in this context. Other studies have shown separate defects in neutrophil cellular processes that go some way toward explaining this functional deficit in response to bacterial challenge, with impaired chemotaxis (12, 15, 20), opsonization (26, 35), and phagocytosis (19, 30) reported.

Conversely, the pattern of neutrophil granule baseline expression confirms these neutrophils are activated in their circulating state in ALD cirrhosis. They have higher levels of CD11b both on their cell surface and intracellularly; by implication they are primed, more adhesive, and liable to interact with the vascular endothelium. An elegant study published in 1983 reporting increased neutrophil adherence to nylon fiber in vitro in the context of ALD cirrhosis corroborates this data (2).

Furthermore, neutrophils from patients with ALD cirrhosis have increased staining of primary and secondary granules intracellularly at baseline and augmented granular release in response to chemotactic and bacterial stimuli when compared against HC. Neutrophils are therefore more likely to release their toxic granular contents in response to lower concentrations of bacterial stimulation and in higher levels than they are in healthy adults; this may lead to inappropriate and/or excessive granule release and tilt the spectrum of granule function toward creating an environment of oxidative stress and damage in host tissue. This paradigm of primed and inappropriately sensitized neutrophils gives weight to the suggestion that dysregulation of the innate immune system in ALD cirrhosis is a double-edged sword, both contributing to the propensity to develop bacterial and fungal sepsis, and, in terms of granule hyperresponsiveness, the propensity to suffer the serious sequelae of sepsis.

When we compared neutrophil granular phenotype in ALD cirrhosis patients who are actively drinking alcohol against those who are abstinent, intracellular content of both primary and secondary granules was significantly elevated in the abstinent cohort but these changes were not seen in patients who were actively drinking. Neutrophil activation and the production of ROS have been shown to lead to hepatic injury in this context (4), and selective gut decontamination can prevent hepatic injury related to alcohol toxicity (1). The effect of active alcohol consumption appears to dampen the neutrophil inflammatory responses across the board of neutrophil granular phenotype; this is in keeping with observations of the effects of alcohol on neutrophil ROS production (27, 34). Rebound hyperresponsiveness and increased neutrophil degranulation may cause bystander damage and worsen liver injury on cessation of alcohol consumption. This observation provides credence in the form of a proposed immunological mechanism for the frequently observed phenomenon of initial clinical deterioration on cessation of alcohol consumption; however, further mechanistic work is required here. We feel that the inclusion of actively drinking and abstinent ALD cirrhotic patients in our study is likely to explain the differences in observed granular phenotype described in recent papers from Markwick et. al (24) and Boussif et. al (9), whose patient cohorts were actively drinking patients with ALD cirrhosis and acute alcoholic hepatitis. Further studies are warranted to investigate the effects of active alcohol consumption upon neutrophil granule function, particularly interrogating whether this is a direct inhibitory effect on neutrophils or is related to a reduction in neutrophil priming via manipulation of the enteric microbiota and circulatory endotoxin burden.

Infection and its propensity to evolve into severe sepsis and MOF in the context of cirrhosis remain a huge challenge facing patients and clinicians alike. In the face of a tide of rising liver disease, it is crucial that we understand the immunological aberrancies underpinning this propensity toward the development of sepsis and poor patient performance in controlling and fighting infection. This will allow the selective targeting of innate immunological pathways.

GRANTS

D. L Shawcross was funded by a 5-yr Department of Health Higher Education Funding Council for England Clinical Senior Lectureship, and R. D. Abeles held a Department of Health NIHR Clinical Research Ph.D. Fellowship for the duration of the study. This study was also funded by a Young Investigator Grant awarded to D. L. Shawcross from the Royal Society from 2010 to 2012. Additional laboratory consumables were also funded from the Isaac Schapera Fund. We acknowledge the support of Medical Research Council (MRC) Centre for Transplantation, King's College London, UK-MRC Grant MR/J006742/1, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant 1U01-AA-021908, and the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy's and St. Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust and King's College London.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.H.T. and D.L.S. conceived and designed research; T.H.T., G.K.M.V., R.D.A., and P.K.M. performed experiments; T.H.T. and P.K.M. analyzed data; T.H.T. and D.L.S. interpreted results of experiments; T.H.T. prepared figures; T.H.T. drafted manuscript; T.H.T., G.K.M.V., J.M.R., and D.L.S. edited and revised manuscript; T.H.T., P.K.M., and D.L.S. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the National Health Services (NHS), the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), or the Department of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi Y, Moore LE, Bradford BU, Gao W, Thurman RG. Antibiotics prevent liver injury in rats following long-term exposure to ethanol. Gastroenterology 108: 218–224, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altin M, Rajkovic IA, Hughes RD, Williams R. Neutrophil adherence in chronic liver disease and fulminant hepatic failure. Gut 24: 746–750, 1983. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.8.746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amulic B, Cazalet C, Hayes GL, Metzler KD, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil function: from mechanisms to disease. Annu Rev Immunol 30: 459–489, 2012. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arthur MJ, Bentley IS, Tanner AR, Saunders PK, Millward-Sadler GH, Wright R. Oxygen-derived free radicals promote hepatic injury in the rat. Gastroenterology 89: 1114–1122, 1985. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90218-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arvaniti V, D'Amico G, Fede G, Manousou P, Tsochatzis E, Pleguezuelo M, Burroughs AK. Infections in patients with cirrhosis increase mortality four-fold and should be used in determining prognosis. Gastroenterology 139: 1246–1256, 2010. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borregaard N. Current concepts about neutrophil granule physiology. Curr Opin Hematol 3: 11–18, 1996. doi: 10.1097/00062752-199603010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borregaard N. Neutrophils, from marrow to microbes. Immunity 33: 657–670, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borzio M, Salerno F, Piantoni L, Cazzaniga M, Angeli P, Bissoli F, Boccia S, Colloredo-Mels G, Corigliano P, Fornaciari G, Marenco G, Pistara R, Salvagnini M, Sangiovanni A. Bacterial infection in patients with advanced cirrhosis: a multicentre prospective study. Dig Liver Dis 33: 41–48, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boussif A, Rolas L, Weiss E, Bouriche H, Moreau R, Périanin A. Impaired intracellular signaling, myeloperoxidase release and bactericidal activity of neutrophils from patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. J Hepatol 64: 1041–1048, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.British Liver Trust Analysis of Official Mortality Statistics Covering All Deaths Related to Liver Dysfunction Covering ICD K70–76 and Other Codes Including C22–24 (Liver Cancer), and B15–19 (Viral Hepatitis) (Online). https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200809/cmselect/cmhealth/368/368we12.htm [2009].

- 11.Caly WR, Strauss E. A prospective study of bacterial infections in patients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol 18: 353–358, 1993. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(05)80280-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell AC, Dronfield MW, Toghill PJ, Reeves WG. Neutrophil function in chronic liver disease. Clin Exp Immunol 45: 81–89, 1981. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cham BP, Gerrard JM, Bainton DF. Granulophysin is located in the membrane of azurophilic granules in human neutrophils and mobilizes to the plasma membrane following cell stimulation. Am J Pathol 144: 1369–1380, 1994. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cramer E, Pryzwansky KB, Villeval JL, Testa U, Breton-Gorius J. Ultrastructural localization of lactoferrin and myeloperoxidase in human neutrophils by immunogold. Blood 65: 423–432, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeMeo AN, Andersen BR, English DK, Peterson J. Defective chemotaxis associated with a serum inhibitor in cirrhotic patients. N Engl J Med 286: 735–740, 1972. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197204062861401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ducker TP, Skubitz KM. Subcellular localization of CD66, CD67, and NCA in human neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol 52: 11–16, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fagiuoli S, Colli A, Bruno R, Burra P, Craxi A, Gaeta GB, Grossi P, Mondelli MU, Puoti M, Sagnelli E, Stefani S, Toniutto P. Management of infections in cirrhotic patients: report of a consensus conference. Dig Liver Dis 46: 204–212, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fasolato S, Angeli P, Dallagnese L, Maresio G, Zola E, Mazza E, Salinas F, Donà S, Fagiuoli S, Sticca A, Zanus G, Cillo U, Frasson I, Destro C, Gatta A. Renal failure and bacterial infections in patients with cirrhosis: epidemiology and clinical features. Hepatology 45: 223–229, 2007. doi: 10.1002/hep.21443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feliu E, Gougerot MA, Hakim J, Cramer E, Auclair C, Rueff B, Boivin P. Blood polymorphonuclear dysfunction in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Eur J Clin Invest 7: 571–577, 1977. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1977.tb01653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fiuza C, Salcedo M, Clemente G, Tellado JM. In vivo neutrophil dysfunction in cirrhotic patients with advanced liver disease. J Infect Dis 182: 526–533, 2000. doi: 10.1086/315742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, Kremers W, Therneau TM, Kosberg CL, D’Amico G, Dickson ER, Kim WR. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology 33: 464–470, 2001. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirsch R, Woodburne VE, Shephard EG, Kirsch RE. Patients with stable uncomplicated cirrhosis have normal neutrophil function. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 15: 1298–1306, 2000. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maddrey WC, Boitnott JK, Bedine MS, Weber FL Jr, Mezey E, White RI Jr. Corticosteroid therapy of alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 75: 193–199, 1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Markwick LJ, Riva A, Ryan JM, Cooksley H, Palma E, Tranah TH, Manakkat Vijay GK, Vergis N, Thursz M, Evans A, Wright G, Tarff S, O’Grady J, Williams R, Shawcross DL, Chokshi S. Blockade of PD1 and TIM3 restores innate and adaptive immunity in patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis. Gastroenterology 148: 590–602.e10, 2015. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mookerjee RP, Stadlbauer V, Lidder S, Wright GA, Hodges SJ, Davies NA, Jalan R. Neutrophil dysfunction in alcoholic hepatitis superimposed on cirrhosis is reversible and predicts the outcome. Hepatology 46: 831–840, 2007. doi: 10.1002/hep.21737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ono Y, Watanabe T, Matsumoto K, Ito T, Kunii O, Goldstein E. Opsonophagocytic dysfunction in patients with liver cirrhosis and low responses to tumor necrosis factor-alpha and lipopolysaccharide in patients' blood. J Infect Chemother 10: 200–207, 2004. doi: 10.1007/s10156-004-0321-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parlesak A, Schäfer C, Paulus SB, Hammes S, Diedrich JP, Bode C. Phagocytosis and production of reactive oxygen species by peripheral blood phagocytes in patients with different stages of alcohol-induced liver disease: effect of acute exposure to low ethanol concentrations. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 27: 503–508, 2003. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000056688.27111.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prokopowicz Z, Marcinkiewicz J, Katz DR, Chain BM. Neutrophil myeloperoxidase: soldier and statesman. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 60: 43–54, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s00005-011-0156-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg 60: 646–649, 1973. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800600817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajkovic IA, Williams R. Abnormalities of neutrophil phagocytosis, intracellular killing and metabolic activity in alcoholic cirrhosis and hepatitis. Hepatology 6: 252–262, 1986. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840060217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sengelov H, Kjeldsen L, Borregaard N. Control of exocytosis in early neutrophil activation. J Immunol 150: 1535–1543, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sengeløv H, Kjeldsen L, Diamond MS, Springer TA, Borregaard N. Subcellular localization and dynamics of Mac-1 (alpha m beta 2) in human neutrophils. J Clin Invest 92: 1467–1476, 1993. doi: 10.1172/JCI116724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taïeb J, Mathurin P, Elbim C, Cluzel P, Arce-Vicioso M, Bernard B, Opolon P, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Poynard T, Chollet-Martin S. Blood neutrophil functions and cytokine release in severe alcoholic hepatitis: effect of corticosteroids. J Hepatol 32: 579–586, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(00)80219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor NJ, Manakkat Vijay GK, Abeles RD, Auzinger G, Bernal W, Ma Y, Wendon JA, Shawcross DL. The severity of circulating neutrophil dysfunction in patients with cirrhosis is associated with 90-day and 1-year mortality. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 40: 705–715, 2014. doi: 10.1111/apt.12886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wyke RJ, Rajkovic IA, Williams R. Impaired opsonization by serum from patients with chronic liver disease. Clin Exp Immunol 51: 91–98, 1983. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]