Abstract

The activity of fumarase, an enzyme in the tricarboxylic acid cycle, is lower in Dahl salt-sensitive SS rats compared with SS.13BN rats. SS.13BN rats have a Brown Norway (BN) allele of fumarase and exhibit attenuated hypertension. The SS allele of fumarase differs from the BN allele by a K481E sequence variation. It remains unknown whether higher fumarase activities can attenuate hypertension and whether the mechanism is relevant without the K481E variation. We developed SS-TgFh1 transgenic rats overexpressing fumarase on the background of the SS rat. Hypertension was attenuated in SS-TgFh1 rats. Mean arterial pressure in SS-TgFh1 rats was 20 mmHg lower than transgene-negative SS littermates after 12 days on a 4% NaCl diet. Fumarase overexpression decreased H2O2, while fumarase knockdown increased H2O2. Ectopically expressed BN form of fumarase had higher specific activity than the SS form. However, sequencing of more than a dozen rat strains indicated most rat strains including salt-insensitive Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats had the SS allele of fumarase. Despite that, total fumarase enzyme activity in the renal medulla was still higher in SD rats than in SS rats, which was associated with higher expression of fumarase in SD. H2O2 can suppress the expression of fumarase. Renal medullary interstitial administration of fumarase siRNA in SD rats resulted in higher blood pressure on the high-salt diet. These findings indicate elevation of total fumarase activity attenuates the development of hypertension and can result from a nonsynonymous sequence variation in some rat strains and higher expression in other rat strains.

Keywords: hypertension, metabolism, fumarase, kidney, genetics

emerging evidence suggests abnormalities in the fundamental processes of cellular intermediary metabolism could contribute to the development of essential hypertension, a major risk factor for cardiovascular and renal diseases (10, 14). Human hypertension is associated with changes in the levels of intermediaries of carbohydrate, lipid, and amino acid metabolism in body fluids (20, 31). Maternally inherited hypertension could result from mutations in the mitochondrial transfer RNA(Ile) and the associated impairment of respiratory capacity (32, 33). Experimental alterations of metabolic intermediaries can influence the development of hypertension (6, 13, 27). Essential hypertension is closely related to lifestyle factors and developmental and aging processes. Metabolic mechanisms provide plausible explanations for these relationships.

Fumarase, or fumarate hydratase, is an enzyme in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle that catalyzes the interconversion of fumarate and L-malate. Fumarase was identified as one of the most dramatically different proteins between Dahl salt-sensitive (SS) rats and SS.13BN rats in a proteomic analysis of the kidney (26). The SS rat is a widely used model of human salt-sensitive hypertension (3, 22). The SS.13BN rat is a consomic strain in which chromosome 13 of the SS genome is replaced by the corresponding chromosome from the salt-resistant Brown Norway (BN) rat. Blood pressure salt-sensitivity is significantly reduced in SS.13BN rats (15). Rat chromosome 13 harbors the gene encoding fumarase, Fh1. The SS allele of fumarase differs from the BN allele by a K481E amino acid sequence variation. Fumarase enzyme activity was lower in the kidneys of SS rats compared with SS.13BN rats despite higher fumarase protein abundance in SS rats (27).

These findings suggest the possibility of a novel mechanism for hypertension involving fumarase insufficiencies. However, whether a higher level of fumarase activity can attenuate the development of hypertension remains to be determined. In addition, the BN rat is phylogenetically distant from most laboratory rat stains (2), raising the question of whether the association between high fumarase activities and normal blood pressure is restricted to rats with the BN allele of fumarase. In the present study, we used a transgenic approach to examine the functional role of fumarase in hypertension in SS rats and investigated whether fumarase activities were higher in any normotensive rat strain other than strains harboring the BN allele compared with SS.

METHODS

Animals.

Rats were maintained on the AIN-76A diet (Dyets) with free access to water as described previously (5, 29). All animal research protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Medical College of Wisconsin.

Development of SS-TgFh1 transgenic rats.

SS-Tg(CAG-FH1)A1Mcwi rats (hereafter called SS-TgFh1) were generated by Sleeping Beauty (SB) transpositional transgenesis (8, 9). In brief, a plasmid harboring an SB transposon transgene consisting of the CAG promoter (CMV enhancer, chicken beta actin promoter, and rabbit beta globin intron), Fh1 cDNA cloned from an SS.13BN rat, and rabbit beta globin polyadenylation signal, was injected into SS/JrHsdMcwi (SS) fertilized embryos with an in vitro transcribed source of the SB transposase. A transgenic founder was identified and backcrossed to the SS strain to establish a breeding colony. The precise transposon transgene integration point into the rat genome was identified by linker-mediated PCR as we have previously described (8). Genomic PCR primers FH1A01_F: 5′-TACAAGCAAGATTATCTGTGTCAGG-3′, FH1A01_R: 5-CAGGAAACTGACAATTTGCCTT −3′, and a transposon specific primer 5′-GACTTGTGTCATGCACAAAGTAGATGTCC-3′ were used to determine zygosity.

Western blot.

Western blotting was performed as described previously (16, 26). The primary antibody for fumarase was from Everest, catalog no. EB07874, and used at 1:12,500 dilution. The secondary antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog no. SC-2350, and used at 1:5,000 dilution. The same amount of protein was loaded on each lane, which was confirmed by Coomassie blue staining of the entire membrane after Western blotting (11, 25, 26).

Fumarase activity assay.

Fumarase activity was measured in tissue homogenates as described previously (27). Fumarase activity is conventionally measured in the direction of L-malic acid to fumaric acid because of the ease of the assay. Briefly, tissue specimens were homogenized and sonicated extensively in a cold HEPES solution. The homogenate was centrifuged at 500 g and then 18,000 g. Protein concentrations of the extracts were adjusted to be the same across all of the samples. The reaction recipe was 20 μl of Tris-acetate (pH 7.5), 178 μl of L-malic acid [50 mmol/l prepared in Tris-acetate (pH 7.5)], and 2 μl of the tissue homogenate. Absorbance at 240 nm was monitored at 30 s intervals using the kinetic mode of a microplate reader. One unit (U) of activity was defined as the generation of 1 μmol of fumaric acid/min.

Measurement of blood pressure.

Measurement of blood pressure in conscious, freely moving rats via an indwelling femoral arterial catheter was performed as described previously (19, 27).

Measurement of H2O2.

H2O2 levels were measured in tissue or cell extract or cell culture supernatant using Amplex Red as described previously (27). The measurement was done with or without prior addition of catalase. Catalase-inhibitable signals were used as an index of H2O2 levels.

Cell culture.

Cell culture was performed as described previously (27).

Small hairpin RNA.

Small hairpin (sh)RNA targeting human fumarase or a scrambled shRNA was obtained from Sigma as a glycerol stock. The sequence of the fumarase shRNA was CCGGCCCAACGATCATGTTAATAAACTCGAGTTTATTAACATGATCGTTGGGTTTTTG, with the underlined segments being the stem of the stem-loop structure. The plasmid was prepared and transfected into cultured human renal epithelial cells as described previously (18).

Real-time PCR.

Real-time PCR was performed using the TaqMan chemistry as described previously (21, 34). Primers and probes used were (5′-3′) CGGCCTGCAGTCTGATGAA (forward), AAGATCAGCTCCCCCAAACC (reverse), and ACATTCGCTTCCTCGGTTCTGGTCC (probe) for rat fumarase and GGGATGCTTCAGTTTCCTTTACAG (forward), AGAGACTCATTCATCAGCTTGTTGA (reverse), and TGTATTGGCCTGGATTCCCACCACG (probe) for human fumarase. 18S rRNA was used as internal control.

Sequencing.

The strain sequence comparison was performed as described previously (12), and coding single nucleotide polymorphism was confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Ectopic expression of SS and BN alleles of Fh1.

The coding sequence of the SS and BN alleles of Fh1 gene was PCR-amplified from cDNA obtained from SS and SS.13BN rats, respectively, with the following primers: 5-ATTC GAATTC GCcacc atgaaccgcgcattctgt-3 and 5-ATTC GAATTC tcactttggacccagcatgt-3. An EcoRI site and a Kozak sequence were introduced by PCR simultaneously. Purified 1.5 kb PCR products and pT2-CAG-eGFP expression plasmid were digested with EcoRI. The digested PCR products were inserted into digested pT2-CAG-eGFP and sequenced-verified. Purified plasmids (8 μg) were transfected into 6 cm dishes of HEK293 cells with Lipofectamine 2000. The cells were collected 48 h later for Western blot and activity analysis of fumarase.

Renal medullary interstitial administration of siRNA in conscious rats.

Renal medullary interstitial catheter was chronically implanted, and Stealth siRNA (Invitrogen) was administered with in vivo-jetPEI (Polyplus) by methods we characterized and described previously (19). In brief, a catheter was implanted in the remaining kidney of a uninephrectomized rat and chronically infused to maintain patency. A Stealth siRNA targeting rat fumarase or a scrambled Stealth siRNA was complexed with in vivo-jetPEI at an N/P ratio of 10 in a total volume of 200 μl. The siRNA preparation was injected over 3 min into the renal medullary interstitial catheter after a stable baseline of blood pressure on a 0.4% salt diet was obtained. The rats were switched to a 4% salt diet after the siRNA injection, and blood pressure recording continued for another 5 days. Additional groups of rats were treated similarly and killed 3 days after the siRNA administration for tissue collection to assess the efficiency of fumarase knockdown.

Statistics.

Data are shown as means ± SE. Data were analyzed by Student’s t-test or two-way ANOVA. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Fumarase overexpression attenuates hypertension in SS rats.

We used a transgenic approach to test whether increasing fumarase activity can attenuate hypertension in SS rats. The SB transposon method was used to develop a transgenic rat strain, SS-TgFh1, in which an Fh1 transgene cloned from an SS.13BN rat was inserted into the genome of the SS rat. A transgenic animal was identified harboring a single copy of the transgene inserted on chromosome 13, near 15.54 Mb (sequence tag: TATTTATAACCATTGGAAAGCACACTATTCTTCAGTG), more than 800 kbp away from the nearest annotated gene, Olr1065. A colony was established and maintained by backcrossing hemizygous transgenic animals to the parental SS strain. Transgenic and nontransgenic littermates were used in the studies described below.

Successful overexpression of fumarase in SS-TgFh1 was confirmed in the renal medulla (Fig. 1A), renal cortex, liver, and the left ventricle of the heart by Western blot. The enzymatic activity of fumarase in tissue extract prepared from the renal cortex was increased from 0.23 ± 0.01 U/mg protein in transgene-negative SS littermates to 4.68 ± 0.49 U/mg in SS-TgFh1 (n = 4, P < 0.05). High-salt diet (4% NaCl for 7 days) did not significantly change fumarase activities in transgene-negative littermates or SS-TgFh1 rats (0.25 ± 0.02 and 4.65 ± 0.66 U/mg, respectively, n = 4). The difference in fumarase activity between SS-TgFh1 and SS was greater than that between SS.13BN and SS (27). Therefore, SS-TgFh1 should not be considered an exact reproduction of the fumarase status of SS.13BN but, rather, a model for testing the effect of specifically increasing fumarase activities on hypertension within the genomic context of the SS rat.

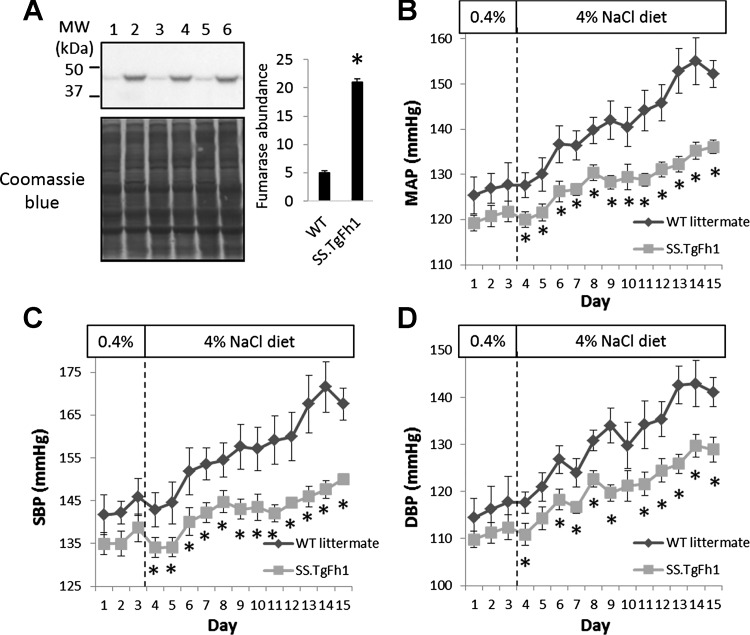

Fig. 1.

Transgenic overexpression of fumarase attenuated hypertension in Dahl salt-sensitive (SS) rats. A: Western blot analysis of fumarase in the renal medulla of SS-TgFh1 (lanes 2, 4, 6) and transgene-negative SS littermates [wild type (WT)] (lanes 1, 3, 5). Coomassie stain of the entire membrane, part of which is shown below the Western blot, was used for normalization. *P < 0.05 vs. WT. B: mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) measured in conscious, freely moving rats via indwelling femoral arterial catheter. Rats were 13–14 wk old on day 1; n = 6 transgene-negative (WT) SS littermates (2 males and 4 females) and 9 SS-TgFh1 (6 males and 3 females). *P < 0.05 vs. WT SS littermate. C: systolic blood pressure (SBP). D: diastolic blood pressure (DBP).

Arterial blood pressure of SS-TgFh1 rats fed a 4% NaCl diet for up to 12 days was significantly and substantially lower than transgene-negative SS littermates (Fig. 1, B–D). Rats were 13 wk old at the time of catheterization. Rats of each genotype included both males and females. Reduction of blood pressure was observed for both systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP). The reduction in mean arterial pressure (MAP) reached ~20 mmHg. Blood pressure of SS-TgFh1 tended to be lower than SS before the initiation of the high-salt diet by ~6 mmHg for MAP, although the differences did not reach statistical significance. Blood pressure of SS rats is known to increase gradually with age even when the rats are maintained on the 0.4% NaCl diet. It remains to be determined whether fumarase attenuates the age-dependent increase of blood pressure in SS rats in addition to blunting high salt-induced hypertension.

Fumarase insufficiency increases oxidative stress.

We investigated potential mechanisms mediating the effect of fumarase on hypertension. Increased levels of H2O2 in the kidney have been shown to contribute to hypertension in SS rats (24). Levels of H2O2 in the renal cortex were significantly lower in SS-TgFh1 rats compared with SS littermates at the end of the 4% NaCl diet treatment (Fig. 2A). Levels of H2O2 were not significantly different between SS-TgFh1 and SS littermates when the rats were maintained on the 0.4% NaCl diet.

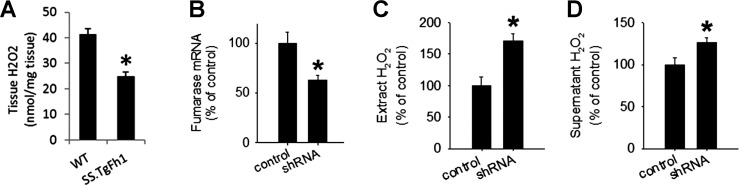

Fig. 2.

Fumarase insufficiency increased H2O2. A: levels of H2O2 in the renal cortex of SS-TgFh1 and transgene-negative SS littermates (WT); n = 6 WT and 11 SS-TgFh1, *P < 0.05. B: knockdown of fumarase in human renal epithelial (HRE) cells by shRNA compared with a control shRNA; n = 3 control shRNA and 4 fumarase shRNA, *P < 0.05. C: H2O2 levels in HRE cell extract following treatment with fumarase shRNA; n = 3 control shRNA and 4 fumarase shRNA, *P < 0.05. D: H2O2 levels in HRE cell culture supernatant following treatment with fumarase shRNA; n = 3 control shRNA and 4 fumarase shRNA, *P < 0.05.

To examine the effect of fumarase on H2O2 in the absence of confounding factors present in whole animals, we knocked down fumarase in cultured human renal epithelial cells (HRE) with shRNA (Fig. 2B). Knockdown of fumarase in HRE cells resulted in significant increases of H2O2 in cell extract and culture supernatant (Fig. 2, C and D).

Sequencing of fumarase gene segment in various rat strains.

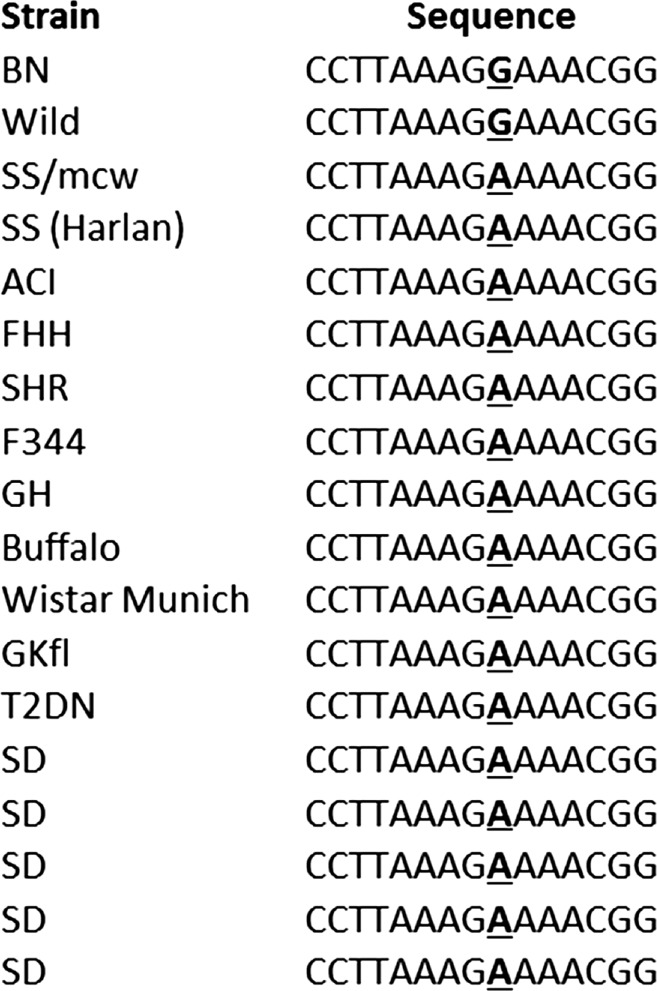

The BN rat is phylogenetically distant from most laboratory rat stain (2). The genomic segment of Fh1 that contains the A1441G sequence variation between the SS and BN alleles, encoding the K481E amino acid sequence variation (27), was Sanger-sequenced in more than a dozen rat strains including strains that are generally normotensive and salt-insensitive, such as Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats. For outbred SD rats, we sequenced five rats obtained from the commercial vendor several months apart. The result confirmed the A1441G variation between SS and BN rats. However, the wild rat was the only one other than the BN rat to possess the G allele. The A allele found in the SS rat was found in all other strains sequenced including the five SD rats (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Sanger sequencing of the fumarase gene Fh1 around nucleotide 1441 in various rat strains. Exon 10 of Fh1 was amplified from genomic DNA. The PCR products were sequenced. Only the sequence around nucleotide 1441 (boldfaced and underlined) is shown. The 5 outbred Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats sequenced were purchased from the vendor several months apart.

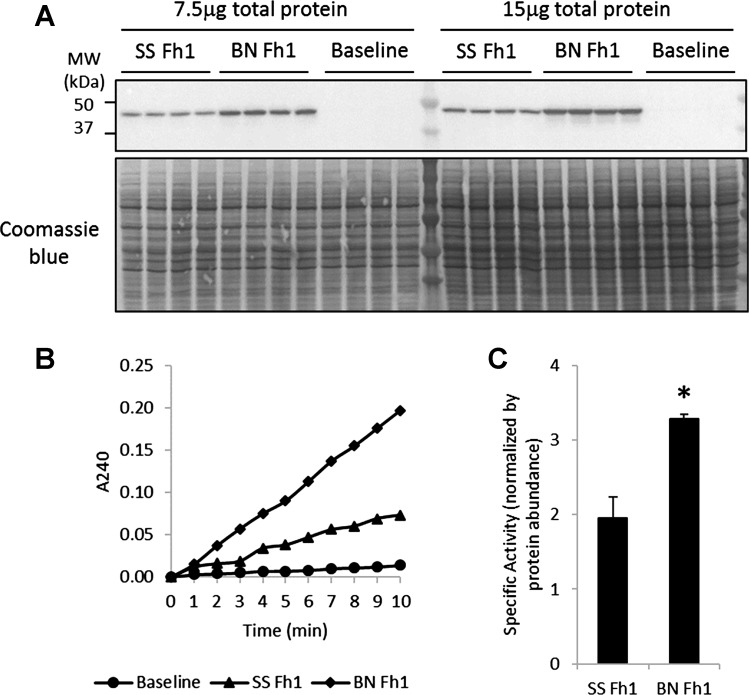

We examined whether the SS and BN forms of fumarase had different activities by ectopically expressing them in HEK293 cells and measuring fumarase enzymatic activities (Fig. 4, A and B). Activities specific to the ectopically expressed fumarase were calculated by normalizing activities by protein abundance after the activities and abundance in untransfected cells were subtracted. Two different amounts of protein (7.5 and 15 μg) were loaded for each sample in the Western blot analysis to confirm that band densities were proportional to protein abundance (Fig. 4A). The specific activity of the SS form of fumarase was significantly lower than the BN form (Fig. 4C), consistent with results from kidney tissues in SS and SS.13BN rats that we previously reported (24).

Fig. 4.

The enzymatic activity of the SS form of fumarase was lower than the Brown Norway (BN) form. SS and BN forms of fumarase (Fh1) were cloned and ectopically expressed in HEK293 cells. A: Western blot analysis of fumarase with 7.5 or 15 μg of total protein loaded per lane. SS Fh1 and BN Fh1, cells transfected with SS and BN forms of Fh1, respectively; baseline, untransfected cells. B: representative tracings from enzymatic activity analysis of fumarase. C: the specific activity of the BN form of fumarase was higher than the SS form. Specific activities were calculated as total activities normalized by fumarase protein abundance estimated from Western blot. Fumarase activities and abundance in untransfected cells (baseline) were subtracted from transfected cells before the calculation of specific activities. *P < 0.05.

The sequencing result suggested the fumarase insufficiency we previously reported in SS rats might be present only in comparison with BN rats, which would suggest the protection from salt-sensitive hypertension in most rat strains might not involve fumarase. Alternatively, the protection from hypertension in strains other than those with the BN allele might still involve fumarase but through mechanisms un-related to the K481E variation. In addition, the allelic effects of the polymorphism resulting in the K481E substitution might be of variable penetrance in rat strains that have different genomic backgrounds (23).

Upregulation of fumarase expression in SD rats and its role in hypertension.

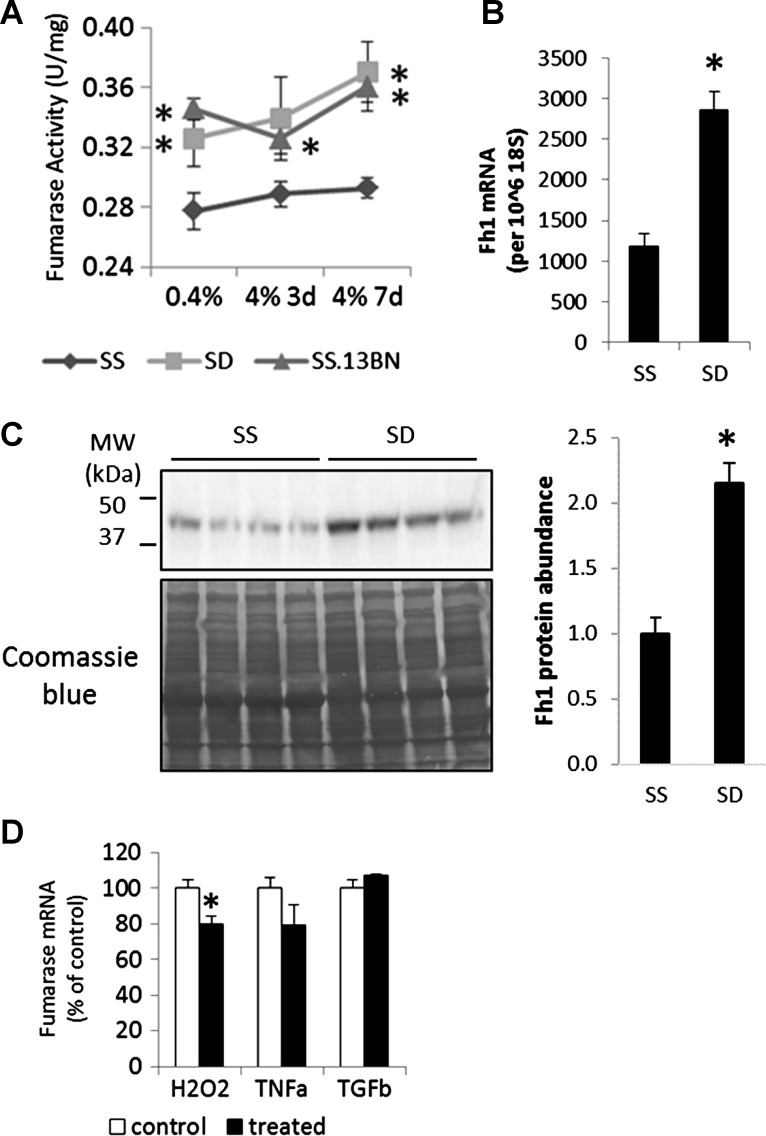

We measured fumarase enzyme activities in the kidneys of male SS, consomic SS.13BN (containing the BN allele of fumarase), and SD (containing the SS allele of fumarase) rats. We confirmed higher fumarase activities in the renal medulla of SS.13BN rats compared with SS rats (Fig. 5A), similar to previous reports (27). Importantly, fumarase activities were also significantly higher in SD rats compared with SS rats (Fig. 5A), suggesting mechanisms unrelated to the K481E variation could lead to differences in fumarase activities between salt-insensitive and salt-sensitive rat strains.

Fig. 5.

Fumarase activities and expression were higher in SD rats than SS rats. A: fumarase activities in tissue extract from the renal medulla; n = 6 for 0.4% NaCl diet group and 3 for each of the 4% NaCl diet group for SS and SS.13BN, n = 9 and 6 for SD, *P < 0.05 vs. SS under the same dietary condition. B: abundance of fumarase mRNA in the renal medulla; n = 7 SS and 3 SD, *P < 0.05. C: Western blot analysis of fumarase protein in the renal medulla; n = 4, *P < 0.05. D: effect of H2O2 (100 μM, 48 h), TNF-α (25 ng/ml, 24 h), and TGF-β (3 ng/ml, 24 h) on fumarase mRNA abundance in HRE cells; n = 4–8, *P < 0.05 vs. the corresponding vehicle control.

We examined the expression level of fumarase. The higher fumarase activity in SD rats as compared with SS rats was associated with higher fumarase mRNA and protein abundance in SD rats (Fig. 5, B and C). To understand why fumarase expression was lower in SS rats compared with SD rats, we examined the effect of H2O2, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) on fumarase mRNA abundance in HRE cells. H2O2, TNF-α, and TGF-β represent the oxidative, inflammatory, and fibrotic milieu known to the present in the kidneys of SS rats. Treatment with H2O2 for 48 h at a noncytotoxic concentration (100 μM) significantly decreased fumarase abundance (Fig. 5D). The effect was modest, suggesting H2O2 might be one of several factors that could suppress fumarase expression in SS rats. A shorter period (24 h) of treatment with H2O2 did not decrease fumarase abundance, suggesting the effect of H2O2 on fumarase might be time-dependent. TNF-α tended to decrease fumarase abundance, but the effect did not reach statistical significance. TGF-β did not influence fumarase abundance.

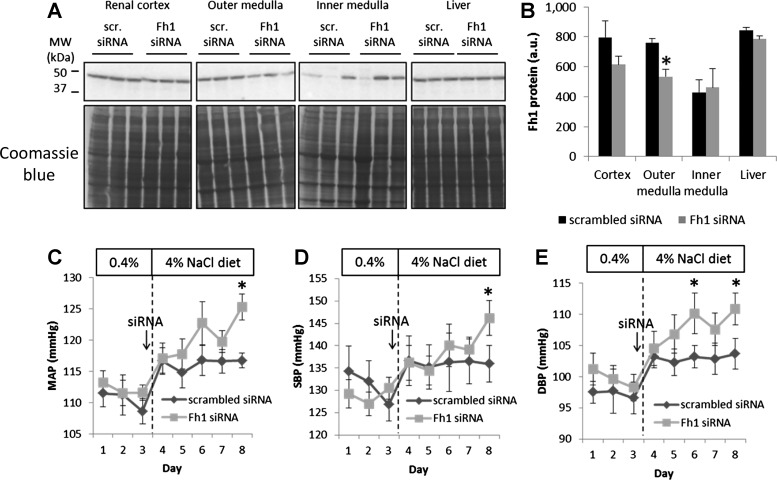

We examined whether the higher levels of fumarase in the kidneys of SD rats contributed to the protection of SD rats from the development of salt-induced hypertension. We used renal medullary interstitial administration of siRNA complexed with a polyethylenimine, an approach for local gene knockdown in the kidney that we had developed and characterized previously (19). Renal medullary interstitial administration of an siRNA targeting rat fumarase led to significant knockdown of fumarase protein in the renal outer medulla measured on day 3 after the administration of siRNA (Fig. 6, A and B). The degree of knockdown was in the same range as previous studies using a similar approach (19). Fumarase protein abundance tended to decrease in the renal cortex, although it did not reach statistical significance. The treatment did not have any significant effect on fumarase abundance in the renal inner medulla or liver (Fig. 6, A and B).

Fig. 6.

Fumarase in the kidney contributed to protecting SD rats from developing salt-induced hypertension. A: renal medullary interstitial administration of an siRNA targeting fumarase knocked down fumarase in the outer medulla. Part of the Coomassie blue stain used for normalization is shown under each corresponding Western blot. B: densitometry quantification of the blots shown in A normalized by Coomassie stains; n = 6, *P < 0.05 vs. rats treated with scrambled control siRNA. C: mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) of SD rats treated with renal medullary interstitial administration of siRNA; n = 7 for scrambled siRNA and 8 for fumarase (Fh1) siRNA. *P < 0.05 vs. scrambled control siRNA. D: systolic blood pressure (SBP). E: diastolic blood pressure (DBP).

Blood pressure was analyzed for 5 days after the siRNA treatment since the effect of the siRNA was expected to last only for a few days (19). Renal medullary interstitial administration of the siRNA targeting fumarase resulted in significant increases in MAP as well as SBP and DBP after the rats were switched to a high-salt diet (Fig. 6, C–E). The magnitude of the blood pressure increase was modest, which is to be expected given the salt-insensitive nature of SD rats. The effect appeared to be more prominent for DBP (Fig. 6E).

DISCUSSION

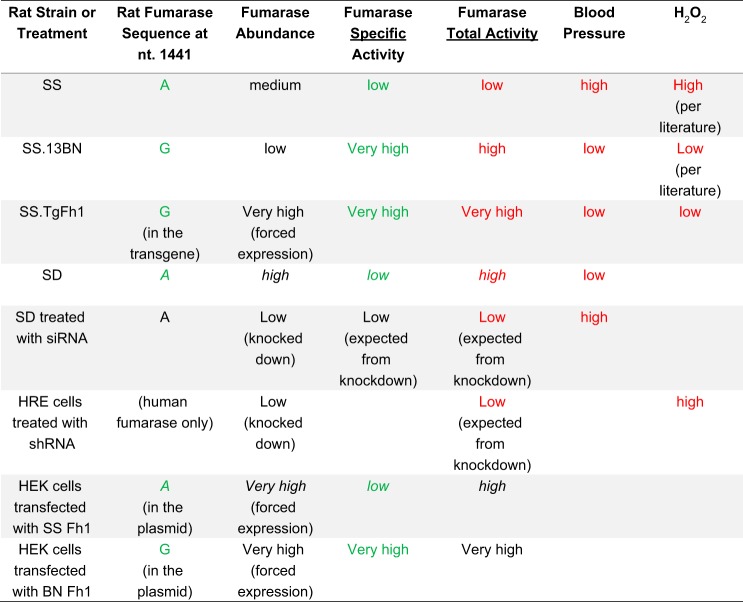

The findings of the present study, as summarized in Fig. 7, consistently indicate that elevation of total fumarase activity can attenuate the development of hypertension in rats. In addition, elevation of total fumarase activity, compared with the SS rat, is achieved by having the BN allele of fumarase in some rat strains. In rat strains such as SD, which share the SS allele of fumarase, elevation of total fumarase activity is achieved by higher expression of fumarase.

Fig. 7.

Summary of experimental models and results. Findings shown in green consistently support the conclusion that fumarase with G at nucleotide 1441 has higher specific activities than fumarase with A at 1441. Findings shown in italics indicate that high total fumarase activities can be achieved by having higher fumarase abundance even when the genotype is A at nucleotide 1441. Findings shown in red consistently support the conclusion that high total fumarase activities lead to lower blood pressure and less H2O2. Specific activity of fumarase was calculated by dividing total activity by protein abundance.

These findings are consistent with a significant role for mitochondrial intermediary metabolism in hypertension (7, 14, 30). Succinate, which is upstream of fumarate in the TCA cycle, can stimulate renin release from the kidney and increase blood pressure in SD rats (6). The hypertensive effect of succinate was abolished in mice deficient of the G protein-coupled receptor GPR91. GPR91 also mediates high glucose-induced release of renin (28). Activities of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation in renal proximal tubule cells are higher in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) than in normotensive Wistar-Kyoto rats (WKY) (13). Dichloroacetate, an inhibitor of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase in the mitochondrial matrix, increased SBP in WKY and SHR. Complex IV activities in brain mitochondria were reported to be higher in SHR than WKY when the rats were 1 mo old but lower when the rats were 7 mo old (1). In addition, cells carrying a mutation in the mitochondrial tRNA(Ile) gene associated with maternally inherited hypertension exhibit a reduced rate of mitochondrial translation and respiratory capacity (32). Mice with adipose-specific deficiency of fumarase are protected against obesity, which appears to result from mitochondrial energy depletion and subsequent reduction of triglyceride synthesis (35). Taken together, these findings suggest disturbances at several points of mitochondrial intermediary metabolism can influence blood pressure via mechanisms that may or may not involve bioenergetics.

Increased H2O2 in the kidney is a plausible link between fumarase insufficiencies and hypertension in SS rats. High-salt diet and high blood pressure are associated with increased levels of H2O2 in the kidneys of SS rats (24). The increase of H2O2 exacerbates hypertension since renal interstitial administration of catalase, which scavenges H2O2, attenuates hypertension in SS rats (24). The current study suggests transgenic overexpression of fumarase might attenuate salt-induced hypertension in SS rats by blunting the increase of renal H2O2. The role of H2O2 is further supported by previous findings that fumarate precursor dimethyl-fumarate increases H2O2 in rat kidneys and exacerbates salt-induced hypertension (27). Dimethyl-fumarate (27) or fumarase knockdown increases H2O2 in HRE cells. In addition, the current study shows that H2O2 can decrease fumarase abundance, consistent with a recent report showing that overexpression of NADPH oxidase isoform NOX4 in podocytes led to reduced fumarase levels (36). These findings suggest the presence of a vicious cycle in the kidneys of SS rats in which increased H2O2 downregulates fumarase and fumarase insufficiency leads to further increase in H2O2. The relationship between dietary salt intake and direct determinants of fumarase expression, including genetic, humoral, or other factors, remains to be fully elucidated.

It remains to be investigated how fumarase insufficiencies lead to increased H2O2 and whether mechanisms other than H2O2 are involved in the effect of fumarase on blood pressure. The cell culture data in the current study as well as previous studies (27) suggest fumarase and fumarate might have effects on H2O2 that are independent of hypertension or high salt. The blood pressure of SS-TgFh1 tended to be lower than SS littermates when the rats were on the 0.4% NaCl, although the difference did not reach statistical significance. H2O2 levels in the kidney were not lower in SS-TgFh1 at this point, suggesting the involvement of mechanisms other than H2O2.

The siRNA experiment in SD rats takes advantage of a renal interstitial injection approach that has been used by more than a dozen laboratories to achieve kidney-specific administration of experimental agents, an approach that we have further developed to deliver siRNA (19). The findings support an important role of renal fumarase, particularly renal outer medullary fumarase, in hypertension. This is consistent with the well-established significance of the kidney including the renal outer medulla in the development of hypertension (4). The transgenic overexpression in SS-TgFh1 rats was not tissue specific. It remains to be determined whether the effect of fumarase on hypertension in SS-TgFh1 rats involves organs other than the kidney.

The present study is an example of how identification of rare mutations in a gene can lead to the discovery of broader relevance of the gene. Identification of rare mutations associated with hypertension or hypotension has provided important insights into the physiological basis of blood pressure regulation (17). Yet it has been challenging to find the relevance of many of these genes to hypertension in larger populations. The K481E sequence variation in fumarase is a rare mutation in the context of laboratory rat strains. Yet SD rats exhibit fumarase enzyme activities comparable to rats with the BN allele of fumarase even though SD rats have the SS allele of fumarase. This appears to be achieved in SD rats by upregulation of fumarase expression.

It would be important to further extend this line of logic and test whether the fumarase mechanism, discovered through a “rare” mutation in rats, is relevant to human hypertension. Rare loss-of-function mutations of fumarase are present in human, although their frequency might be too low for testing whether they have any modest effect on hypertension. It would be interesting to see if ongoing efforts in whole exome and whole genome sequencing would identify association between blood pressure and any common sequence variations in fumarase.

The analysis of kidney tissues in our previous study (27) and the ectopic expression experiment in the current study both indicate the K481E sequence variation influences the specific enzymatic activity of fumarase after correction for fumarase protein abundance. Whether or how the K481E variation might influence fumarase protein abundance appears to depend on cellular context. In the kidneys of SS rats, fumarase abundance was increased compared with SS.13BN rats in an apparently insufficient attempt to compensate for the ineffective fumarase enzyme (27). In HEK293 cells, however, the abundance of ectopically expressed SS form of fumarase was lower than the BN form. Regardless of the effect on abundance, the specific activity of SS fumarase, after correction for abundance, was lower than the BN form in vivo (27) and in vitro.

The findings of the current study have provided further support for an important role of cellular intermediary metabolism in the regulation of blood pressure (14). Human tissues directly relevant to blood pressure regulation are not readily available for metabolic analysis, and one should be cautious in extrapolating changes in metabolite levels in the blood or urine to changes in cellular metabolism or disease mechanisms. Nevertheless, metabolomic analyses have identified associations between hypertension and levels of several TCA cycle-related metabolites and other metabolites in body fluids (20, 31). Additional metabolomic analysis in patients for which environmental factors such as dietary salt intake are controlled would be valuable, as would clinical studies examining effects of altering cellular metabolism on blood pressure.

GRANTS

This work was supported by US National Institutes of Health Grant HL-116264-7861 (M. Liang) and the National Science Foundation of China Grants 81270767 and 81570655 (Z. Tian).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.L. and Z.T. conceived and designed research; K.U., Y.L., A.M.G., Y.C., J.L., M.A.B., M.G., Y.H., and Z.T. performed experiments and analyzed data; M.L. drafted manuscript; K.U., Y.L., A.M.G., Y.C., J.L., M.A.B., M.G., Y.H., Z.T., and M.L. edited and approved manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Current address for J. Lazar: HudsonAlpha Inst. for Biotechnology, Huntsville, AL 35806.

REFERENCES

- 1.Calderón-Cortés E, Cortés-Rojo C, Clemente-Guerrero M, Manzo-Avalos S, Villalobos-Molina R, Boldogh I, Saavedra-Molina A. Changes in mitochondrial functionality and calcium uptake in hypertensive rats as a function of age. Mitochondrion 8: 262–272, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Canzian F. Phylogenetics of the laboratory rat Rattus norvegicus. Genome Res 7: 262–267, 1997. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cowley AW., Jr The genetic dissection of essential hypertension. Nat Rev Genet 7: 829–840, 2006. doi: 10.1038/nrg1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cowley AW Jr, Mattson DL, Lu S, Roman RJ. The renal medulla and hypertension. Hypertension 25: 663–673, 1995. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.25.4.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geurts AM, Mattson DL, Liu P, Cabacungan E, Skelton MM, Kurth TM, Yang C, Endres BT, Klotz J, Liang M, Cowley AW Jr. Maternal diet during gestation and lactation modifies the severity of salt-induced hypertension and renal injury in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension 65: 447–455, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He W, Miao FJ, Lin DC, Schwandner RT, Wang Z, Gao J, Chen JL, Tian H, Ling L. Citric acid cycle intermediates as ligands for orphan G-protein-coupled receptors. Nature 429: 188–193, 2004. doi: 10.1038/nature02488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.He X, Liu Y, Usa K, Tian Z, Cowley AW Jr, Liang M. Ultrastructure of mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum in renal tubules of Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 306: F1190–F1197, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00073.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ivics Z, Mátés L, Yau TY, Landa V, Zidek V, Bashir S, Hoffmann OI, Hiripi L, Garrels W, Kues WA, Bösze Z, Geurts A, Pravenec M, Rülicke T, Izsvák Z. Germline transgenesis in rodents by pronuclear microinjection of Sleeping Beauty transposons. Nat Protoc 9: 773–793, 2014. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katter K, Geurts AM, Hoffmann O, Mátés L, Landa V, Hiripi L, Moreno C, Lazar J, Bashir S, Zidek V, Popova E, Jerchow B, Becker K, Devaraj A, Walter I, Grzybowksi M, Corbett M, Filho AR, Hodges MR, Bader M, Ivics Z, Jacob HJ, Pravenec M, Bosze Z, Rülicke T, Izsvák Z. Transposon-mediated transgenesis, transgenic rescue, and tissue-specific gene expression in rodents and rabbits. FASEB J 27: 930–941, 2013. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-205526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotchen TA, Cowley AW Jr, Liang M. Ushering hypertension into a new era of precision medicine. JAMA 315: 343–344, 2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kriegel AJ, Fang Y, Liu Y, Tian Z, Mladinov D, Matus IR, Ding X, Greene AS, Liang M. MicroRNA-target pairs in human renal epithelial cells treated with transforming growth factor beta 1: a novel role of miR-382. Nucleic Acids Res 38: 8338–8347, 2010. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lazar J, O’Meara CC, Sarkis AB, Prisco SZ, Xu H, Fox CS, Chen MH, Broeckel U, Arnett DK, Moreno C, Provoost AP, Jacob HJ. SORCS1 contributes to the development of renal disease in rats and humans. Physiol Genomics 45: 720–728, 2013. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00089.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee H, Abe Y, Lee I, Shrivastav S, Crusan AP, Hüttemann M, Hopfer U, Felder RA, Asico LD, Armando I, Jose PA, Kopp JB. Increased mitochondrial activity in renal proximal tubule cells from young spontaneously hypertensive rats. Kidney Int 85: 561–569, 2014. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liang M. Hypertension as a mitochondrial and metabolic disease. Kidney Int 80: 15–16, 2011. doi: 10.1038/ki.2011.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liang M, Lee NH, Wang H, Greene AS, Kwitek AE, Kaldunski ML, Luu TV, Frank BC, Bugenhagen S, Jacob HJ, Cowley AW Jr. Molecular networks in Dahl salt-sensitive hypertension based on transcriptome analysis of a panel of consomic rats. Physiol Genomics 34: 54–64, 2008. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00031.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang M, Pietrusz JL. Thiol-related genes in diabetic complications: a novel protective role for endogenous thioredoxin 2. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 77–83, 2007. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000251006.54632.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lifton RP, Gharavi AG, Geller DS. Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension. Cell 104: 545–556, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Y, Park F, Pietrusz JL, Jia G, Singh RJ, Netzel BC, Liang M. Suppression of 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 with RNA interference substantially attenuates 3T3-L1 adipogenesis. Physiol Genomics 32: 343–351, 2008. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00067.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Y, Singh RJ, Usa K, Netzel BC, Liang M. Renal medullary 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 in Dahl salt-sensitive hypertension. Physiol Genomics 36: 52–58, 2008. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.90283.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menni C, Graham D, Kastenmüller G, Alharbi NH, Alsanosi SM, McBride M, Mangino M, Titcombe P, Shin SY, Psatha M, Geisendorfer T, Huber A, Peters A, Wang-Sattler R, Xu T, Brosnan MJ, Trimmer J, Reichel C, Mohney RP, Soranzo N, Edwards MH, Cooper C, Church AC, Suhre K, Gieger C, Dominiczak AF, Spector TD, Padmanabhan S, Valdes AM. Metabolomic identification of a novel pathway of blood pressure regulation involving hexadecanedioate. Hypertension 66: 422–429, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mladinov D, Liu Y, Mattson DL, Liang M. MicroRNAs contribute to the maintenance of cell-type-specific physiological characteristics: miR-192 targets Na+/K+-ATPase β1. Nucleic Acids Res 41: 1273–1283, 2013. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rapp JP. Genetic analysis of inherited hypertension in the rat. Physiol Rev 80: 135–172, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rapp JP. Theoretical model for gene-gene, gene-environment, and gene-sex interactions based on congenic-strain analysis of blood pressure in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Physiol Genomics 45: 737–750, 2013. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00046.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor NE, Cowley AW Jr. Effect of renal medullary H2O2 on salt-induced hypertension and renal injury. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R1573–R1579, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00525.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tian Z, Greene AS, Pietrusz JL, Matus IR, Liang M. MicroRNA-target pairs in the rat kidney identified by microRNA microarray, proteomic, and bioinformatic analysis. Genome Res 18: 404–411, 2008. doi: 10.1101/gr.6587008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tian Z, Greene AS, Usa K, Matus IR, Bauwens J, Pietrusz JL, Cowley AW Jr, Liang M. Renal regional proteomes in young Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension 51: 899–904, 2008. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.109173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tian Z, Liu Y, Usa K, Mladinov D, Fang Y, Ding X, Greene AS, Cowley AW Jr, Liang M. Novel role of fumarate metabolism in dahl-salt sensitive hypertension. Hypertension 54: 255–260, 2009. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.129528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toma I, Kang JJ, Sipos A, Vargas S, Bansal E, Hanner F, Meer E, Peti-Peterdi J. Succinate receptor GPR91 provides a direct link between high glucose levels and renin release in murine and rabbit kidney. J Clin Invest 118: 2526–2534, 2008. doi: 10.1172/JCI3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang F, Zhang G, Lu Z, Geurts AM, Usa K, Jacob HJ, Cowley AW, Wang N, Liang M. Antithrombin III/SerpinC1 insufficiency exacerbates renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Kidney Int 88: 796–803, 2015. doi: 10.1038/ki.2015.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang L, Hou E, Wang Z, Sun N, He L, Chen L, Liang M, Tian Z. Analysis of metabolites in plasma reveals distinct metabolic features between Dahl salt-sensitive rats and consomic SS.13(BN) rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 450: 863–869, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.06.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang L, Hou E, Wang L, Wang Y, Yang L, Zheng X, Xie G, Sun Q, Liang M, Tian Z. Reconstruction and analysis of correlation networks based on GC-MS metabolomics data for young hypertensive men. Anal Chim Acta 854: 95–105, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2014.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang S, Li R, Fettermann A, Li Z, Qian Y, Liu Y, Wang X, Zhou A, Mo JQ, Yang L, Jiang P, Taschner A, Rossmanith W, Guan MX. Maternally inherited essential hypertension is associated with the novel 4263A>G mutation in the mitochondrial tRNAIle gene in a large Han Chinese family. Circ Res 108: 862–870, 2011. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.231811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson FH, Hariri A, Farhi A, Zhao H, Petersen KF, Toka HR, Nelson-Williams C, Raja KM, Kashgarian M, Shulman GI, Scheinman SJ, Lifton RP. A cluster of metabolic defects caused by mutation in a mitochondrial tRNA. Science 306: 1190–1194, 2004. doi: 10.1126/science.1102521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu X, Kriegel AJ, Liu Y, Usa K, Mladinov D, Liu H, Fang Y, Ding X, Liang M. Delayed ischemic preconditioning contributes to renal protection by upregulation of miR-21. Kidney Int 82: 1167–1175, 2012. doi: 10.1038/ki.2012.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang H, Wu JW, Wang SP, Severi I, Sartini L, Frizzell N, Cinti S, Yang G, Mitchell GA. Adipose-specific deficiency of fumarate hydratase in mice protects against obesity, hepatic steatosis, and insulin resistance. Diabetes 65: 3396–3409, 2016. doi: 10.2337/db16-0136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.You YH, Quach T, Saito R, Pham J, Sharma K. Metabolomics reveals a key role for fumarate in mediating the effects of NADPH oxidase 4 in diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 466–481, 2016. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015030302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]