Abstract

This study investigated how differences in drug distribution and free fraction at different tumor and tissue sites influence the efficacy of the multikinase inhibitor ponatinib in a patient-derived xenograft model of glioblastoma (GBM). Efficacy studies in GBM6 flank (heterotopic) and intracranial (orthotopic) models showed that ponatinib is effective in the flank but not in the intracranial model, despite a relatively high brain-to-plasma ratio. In vitro binding studies indicated that flank tumor had a higher free (unbound) drug fraction than normal brain. The total and free drug concentrations, along with the tissue-to-plasma ratio (Kp) and its unbound derivative (Kp,uu), were consistently higher in the flank tumor than the normal brain at 1 and 6 hours after a single dose in GBM6 flank xenografts. In the orthotopic xenografts, the intracranial tumor core displayed higher Kp and Kp,uu values compared with the brain-around-tumor (BAT). The free fractions and the total drug concentrations, hence free drug concentrations, were consistently higher in the core than in the BAT at 1 and 6 hours postdose. The delivery disadvantages in the brain and BAT were further evidenced by the low total drug concentrations in these areas that did not consistently exceed the in vitro cytotoxic concentration (IC50). Taken together, the regional differences in free drug exposure across the intracranial tumor may be responsible for compromising efficacy of ponatinib in orthotopic GBM6.

Introduction

Glioblastoma (GBM) is the most common malignant brain tumor in adults, and it is estimated that there will be about 12,000 new cases of GBM in 2017 (Ostrom et al., 2016). To date, no therapeutic agents other than temozolomide (TMZ) and bevacizumab have improved the overall survival (TMZ) or symptoms (bevacizumab) in GBM clinical trials in the past decade (Minniti et al., 2009). Despite rigorous therapies that typically combine surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, only about 17% of patients with GBM survive 2 years or longer (Ostrom et al., 2016). A large number of potent small-molecule compounds have failed to demonstrate efficacy in GBM clinical trials. Although reasons for this lack of progress are multifactorial, the majority of small-molecule compounds have limited distribution to the brain (Oberoi et al., 2016). Many GBMs have partial disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), so that heterogeneous drug delivery into GBM may be a major contributor. In this context, preclinical studies are needed to elucidate further details of underlying obstacles for effective drug delivery and treatment of brain tumors, such as GBM.

Treatment of GBM using targeted agents is complicated by extensive heterogeneity in the molecular and genetic makeup of the tumor (Phillips et al., 2006; Verhaak et al., 2010; Brennan et al., 2013; Parker et al., 2015) and the remarkable spatial heterogeneity in the permeability of the BBB (Jain et al., 2007). Selective tyrosine kinase inhibitors have not been useful to treat GBM. Coupled with heterogeneous drug distribution, dynamic interaction between oncogenic signaling pathways may contribute to the lack of efficacy of the highly targeted kinase inhibitors (Pazarentzos and Bivona, 2015). Upon selective inhibition of a molecular target, the targeted signaling pathway may adapt and activate an alternative “escape” signaling pathway that compensates for the “targeted” inhibition of a single driving oncogene (Pazarentzos and Bivona, 2015). For this reason, multikinase inhibitors are thought to delay such drug-resistance mechanisms (Sierra and Tsao, 2011).

In addition, the tumor-induced inflammatory reactions in GBM often result in heterogeneous permeability of the BBB (Wolburg et al., 2012). Dramatic regional differences in drug delivery are possible in GBM, where some tumor cells reside behind an intact BBB, whereas other cells are in regions where the BBB is “leaky” (Agarwal et al., 2011). Moreover, given the different tissue and tumor compositions at various anatomic sites (Devaud et al., 2014), the active (free) drug concentration could vary simply by differences in off-target binding and/or rapid clearance from certain tumor regions. Thus, design of an ideal molecularly targeted agent for GBM should consider not only overcoming pathway-driven drug resistance, but also the delivery and bioavailability of therapeutic concentration to the infiltrating GBM cells.

Successful, predictive preclinical efficacy studies for the treatment of GBM must use animal models that are representative of human disease, especially with respect to the heterogeneous breakdown of BBB in GBM (Jain et al., 2007) and the extensive abnormalities in molecular drivers of gliomagenesis (Crespo et al., 2015). Extensive tumor characterization has confirmed that the Mayo Clinic GBM patient-derived xenograft (PDX) panel preserves the histomorphological and molecular features of the original patient tumor (Giannini et al., 2005). For this study, we focused on GBM6, a well characterized PDX in the Mayo Clinic GBM xenograft panel. This particular GBM line is resistant to TMZ (Cen et al., 2013) and a selective kinase inhibitor, erlotinib (Sarkaria et al., 2007), when tumors are grown in an orthotopic location. In addition to restricted drug delivery to the brain, a proteomic analysis demonstrated that elevated expression of multiple receptor tyrosine kinases (RET and PDGFR-α) might also contribute to therapeutic resistance to a selective EGFR inhibitor (unpublished data). Therefore, the use of a multikinase inhibitor exhibiting potent activities against these molecular targets is warranted. We identified ponatinib, an Food and Drug Administration–approved treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia, as a candidate multitargeted compound that has a compelling inhibitory potential against these targets in vitro at an IC50 of 0.2 nM against RET and 1.1 nM against PDGFR-α (European Medicines Agency, 2013). Therefore, ponatinib was selected to be a suitable drug to examine how distribution and delivery may influence in vivo treatment efficacy for GBM.

Free (unbound) drug concentration at the site of action is thought to be the therapeutic or pharmacologically active concentration, whereas equilibrium exists between tissue-bound (total) and unbound (free) drugs. The free drug delivery and regional drug distribution have not been extensively studied in the preclinical GBM models. There have been no reports describing variable free drug fraction at different tumor regions and the consequent therapeutic implications in the treatment of brain tumors. In this study, in vivo efficacy of ponatinib, a multikinase inhibitor, was examined in GBM6 flank versus orthotopic xenografts, and subsequently, we evaluated free and total drug distribution of ponatinib in flank tumor and different regions of orthotopic GBM6 tumors. The data presented provide critical insights into the potential therapeutic implications of heterogeneity of free drug distribution in brain tumors.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals, Reagents, and Supplies.

Ponatinib (3-[2-(imidazo[1,2-b]pyridazin-3-yl)ethynyl]-4-methyl-N-{4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl}benzamide) (>99% purity) was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA), imatinib methanesulfonate (4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-N-[4-methyl-3-[(4-pyridin-3-ylpyrimidin-2-yl)amino]phenyl]benzamide methanesulfonate) (>99% purity) was purchased from LC Laboratories, and [2H8]-ponatinib (>98% purity) was purchased from Alsachim SAS (Illkirch, France). Analytical-grade reagents were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA), and cell culture reagents were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Parental pGIPZ lentiviral vector was sourced from Open Biosystems (GE Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO), HEK293T cells were from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), and pCDNA3.1(+)/Luc2 = tdT was from Addgene (Cambridge, MA). A rapid equilibrium dialysis (RED) device, composed of a 96-well base plate and membrane inserts (8-kDa molecular mass cutoff cellulose dialysis membrane), was obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

In Vitro Cell Cultures and Cytotoxicity Assay.

Short-term cultured human primary glioma GBM6 cells were previously characterized (Sarkaria et al., 2006, 2007) and maintained through serial passages in mice via subcutaneous flank implantation in immune-deficient mice (Carlson et al., 2011). Short-term explant cultures were raised in serum-containing medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin) and were used for subcutaneous implantation (Carlson et al., 2011) and in vitro cytotoxicity assay. Explant cultures were plated on 96-well plates in triplicate and treated with ponatinib at varying concentrations. Following a 5-day treatment, the CyQUANT assay (Invitrogen) was performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Lentiviral Vector and Cell Transduction.

To enable precise dissection to separate tumor from surrounding brain tissues, GBM6 cells were genetically modified to express fluorescent protein. In brief, a modified lentivirus vector, pGIPZ-Luc2 = tdT, was developed by replacing turbo green fluorescent protein tag of pGIPZ with a fusion of firefly luciferase (Luc2) and tandem tomato (tdT) red fluorescent protein excised from pcDNA3.1(+)/Luc2 = tdT (Patel et al., 2010). Lentiviral particles were packaged in HEK293T cells, and transduction to primary GBM6 cells was performed in the presence of 5 µg/ml polybrene (MilliporeSigma, Jaffrey, NH) as previously described (Gupta et al., 2014). Stable transductants expressing Luc2 = tdT fusion gene (GBM6-Luc2 = tdT) were selected in 5 µg/ml puromycin, and subsequently propagated as flank tumors.

Tumor-Bearing Animals.

All studies using animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, and all guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals established by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD) were followed. All animals were housed in a standard 12-hour dark/light cycle with unlimited access to food and water.

Studies involving tumor implantation used female athymic nude mice (Hsd:athymic Nude-Foxn1nu; Envigo, Indianapolis, IN) at age 6–7 weeks. Detailed procedures for PDX establishment were previously described (Carlson et al., 2011). In brief, mice were anesthetized using ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg), and intracranially implanted with 3 µl of cell suspension (100,000 cells/µl) at 1 mm anterior and 2 mm lateral from the bregma. Subcutaneous flank tumors were established by injecting the flank of athymic nude mice with 2 million cells suspended in 100 µl of Matrigel/phosphate-buffered saline mixture. For tumor-tissue carving and imaging, orthotopic tumors were established from explant cultures of GBM6-Luc2 = tdT xenograft line and allowed to grow for 3 weeks before extracting brain tissues and dissecting tumors.

Non–Tumor-Bearing Animals.

An equal number of female and male Friend leukemia virus strain B (FVB) wild-type mice (Taconic Biosciences, Inc., Germantown, NY) were used at age 8–14 weeks for all studies using non–tumor-bearing animals. These animals were bred and maintained in the animal housing facility at the Academic Health Center, University of Minnesota.

In Vivo Efficacy of Ponatinib in GBM6 Xenograft Animals.

Mice with established flank tumors of approximately 200 mm3 were randomized and treated with either placebo (N = 9–10; vehicle of 30% polyethylene glycol 400 and 0.5% Tween 80) or ponatinib (N = 10; 30 mg/kg per day) (O’Hare et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2010) via oral gavage until either the mice reached moribund state or the tumor volume exceeded 1,500 mm3. On day 14 postimplantation, intracranial xenografts (N = 8–10) were randomized and treated with the same dosing regimen until moribund. Staff blinded to the treatment group measured flank tumors three times per week and observed the intracranial xenografts daily. Following the tumor implantation, the body weights of animals were monitored at least every other day until the moribund state. Animals were euthanized with carbon dioxide upon reaching each of the endpoints or other health issues noted.

Regional Distribution of Ponatinib in Flank and Intracranial Tumor.

Mice with established GBM6-Luc2 = tdT tumor (flank tumors at least 200 mm3 or orthotopic tumors at 14 days postimplantation) were randomized and treated with a single oral dose of placebo (group 1) or ponatinib (groups 2 and 3), followed by euthanasia at 1 hour (groups 1 and 2) or 6 hours (group 3) postdose. Plasma, flank tumor, thigh muscle (noncancerous), and brain tissues were collected as follows. Brain tissues extracted from orthotopically implanted animals were dissected under tdTomato goggles. The left hemisphere (without tumor) was first separated from the tumor-bearing right hemisphere. The right hemisphere was further carved to the intracranial tumor core and peripheral region called hereafter the brain-around-tumor (BAT). Purity of tissue dissection was confirmed by ex vivo tissue imaging (IVIS Spectrum; PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) as illustrated in Fig. 4. Plasma, tumor, and various parts of brain were flash frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C until liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis or in vitro binding assay.

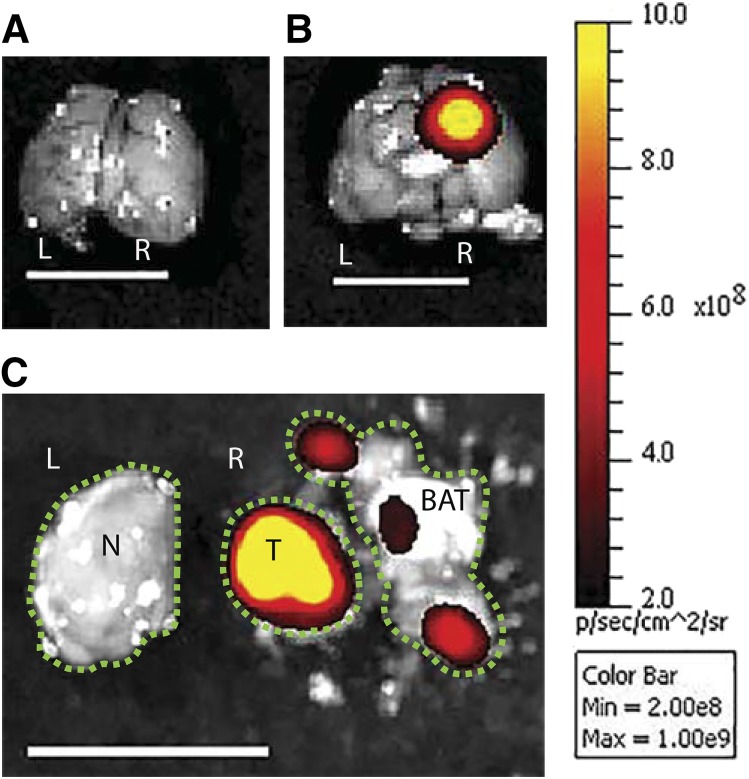

Fig. 4.

A representative image illustrating how different regions of tumor-bearing brain were dissected after visualizing the tumor with ex vivo imaging. The tumor cells expressing red fluorescence (tdTomato) were injected into the right hemisphere. The tumor center with the highest fluorescent signal was defined as the core, the surrounding brain tissue as the BAT, and the contralateral hemisphere as the normal brain. (A) Brain without tumor. (B) Brain with tumor. (C) Separation of tumor and brain. L, left hemisphere; N, normal brain; R, right hemisphere; T, tumor core; line bar, 1 cm, color scale on the right was adjusted to represent each picture shown. The green dotted lines outline each of the intracranial regions.

Plasma and Brain Pharmacokinetics of Ponatinib.

A single dose (30 mg/kg via oral gavage) of ponatinib was administered as an oral suspension (vehicle of 0.5% methylcellulose and 0.2% Tween 80) to FVB wild-type mice. The mice were euthanized by carbon dioxide inhalation at 0.5, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, and 24 hours after oral administration (N = 4 at each time point). Blood was collected via cardiac puncture, transferred to heparinized tubes, and stored on ice. Brain was surgically extracted and rinsed in water. Plasma was separated by centrifuging the blood samples at 3500 rpm at 4°C for 15 minutes. Both plasma and brain samples were stored at −80°C until LC-MS/MS analysis.

In Vitro Binding Assay: Determination of Free (Unbound) Fraction of Ponatinib.

The free fraction in plasma, brain and tumor homogenate (flank tumor, intracranial tumor core, and BAT), and serum-containing medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin) were determined using RED (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as per the manufacturer’s protocol, with some modifications suggested in the literature (Kalvass and Maurer, 2002; Friden et al., 2007). In brief, the tissue homogenate in 3 volumes (w/v; 4-fold dilution) of phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) was prepared by mechanical homogenization (PowerGen 125; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Each matrix was spiked with ponatinib to a final concentration of 10 µM. The spiked matrix (300 µl) was loaded into the sample chamber, and 500 µl of drug-free phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) into the corresponding buffer chamber in triplicate. The chambers, sealed with an adhesive lid, were incubated at 37°C for 4–6 hours on an orbital shaker (300 rpm; ShelLab, Cornelius, OR). Samples after dialysis were stored at −80°C until subsequent LC-MS/MS analysis.

Analytical LC-MS/MS Analysis.

Total drug concentration of ponatinib in various specimens was determined using reverse-phase liquid chromatography (Agilent model 1200 separation system; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) interfaced with TSQ Quantum triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Thermo Finnigan, San Jose, CA) by operating electrospray in positive ion mode and spray voltage at 4500 V. Brain samples were homogenized with 3 tissue volumes of 5% bovine serum albumin (gram/volume) solution using a homogenizer (PowerGen 125; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Ten volumes of 5% bovine serum albumin (gram/volume) solution was added to flank tumor, thigh muscle, and core and peripheral (BAT) regions of intracranial tumor, followed by homogenization using a tissue grinder (Kimble Kontes pellet pestle and cordless motor; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Liquid-liquid extraction was performed for 25-µl aliquot of plasma or 50-µl aliquot of brain, thigh muscle, tumor, or dialysis samples by adding 75 ng of internal standard, 10 volumes of ice-cold ethyl acetate, and finally, 5 volumes of 0.2 M sodium hydroxide (pH 13). Samples were mixed thoroughly by vortexing for 5 minutes, followed by centrifugation at 7500 rpm for 5 minutes (4°C). Organic layer was dried under nitrogen and reconstituted by dissolving the content in 150 µl of mobile phase (acetonitrile and 20 mM ammonium acetate with 0.05% formic acid), and solution was cleared by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 5 minutes (4°C). Five microliters of the sample was injected to the Zorbax XDB Eclipse C18 column (4.6 × 50 mm, 1.8 µm; Agilent Technologies) and subjected to liquid chromatography. Gradient elution with an internal standard (imatinib) was performed to separate analyte for the samples resulting from flank tumor distribution and pharmacokinetic studies. The initial condition of the mobile phase was composed of 30% acetonitrile (B) and 70% 20 mM ammonium acetate with 0.05% formic acid (A; pH 4.5). Gradient elution was achieved as follows: organic phase (B) was increased from 30% to 100% during the first 6 minutes, held at 100% for 2 minutes, decreased to 30% over 0.5 minutes, and held at 30% for the remaining 7.5 minutes. The total run time was 16 minutes, and the flow rate was 0.25 ml/min. The retention times were 7.8 minutes for ponatinib and 4.8 minutes for imatinib, respectively. Mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) transitions were 533.1→260 for ponatinib and 494.3→394.1 for imatinib, respectively.

For all other study samples, a new isocratic method using a deuterated internal standard ([2H8]-ponatinib) was developed to reduce the total run time to 7 minutes. A mobile phase of 45% acetonitrile and 55% 20 mM ammonium acetate with 0.05% formic acid was eluted at a flow rate of 0.35 ml/min. The transition m/z 541→260 was monitored for [2H8]-ponatinib. The retention time was 3.1 minutes for ponatinib and its deuterated internal standard. For each of these LC-MS/MS methods, the calibration curve was sensitive and linear over the range of 0.4–2000 ng/ml (weighting factor of 1/Y2) with a coefficient of variation of less than 15%. All of the measured concentrations were within the range of the calibration curve. Data acquisition and analysis were completed using Xcalibur software (version 2.0.7; Thermo Finnigan).

Calculations.

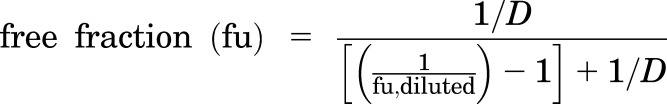

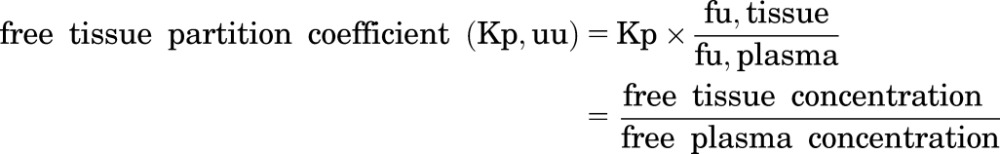

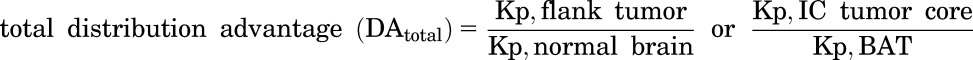

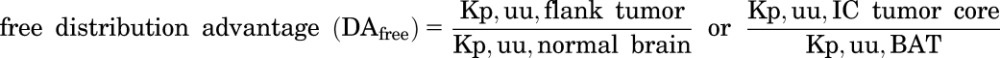

Free fraction (fu) of ponatinib in the various tissue matrices was determined in vitro and calculated using the ratio of buffer concentration to matrix concentration. For matrices other than plasma, the calculation of free fraction accounted for dilution resulting from homogenate preparation (dilution factor, D = 4) as shown here (Kalvass and Maurer, 2002):

|

(1) |

A tissue partition coefficient (e.g., brain-to-plasma ratio or tumor-to-plasma ratio), or Kp, was quantitated by the ratio of total tissue concentration to total plasma concentration. The unbound (free) derivative of Kp (Kp,uu) was determined as follows:

|

(2) |

where fu,tissue and fu,plasma represent the free fraction in the specified tissue and plasma, respectively.

Total and free distribution advantage (DAtotal and DAfree) to the tumor were calculated using the following equations:

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

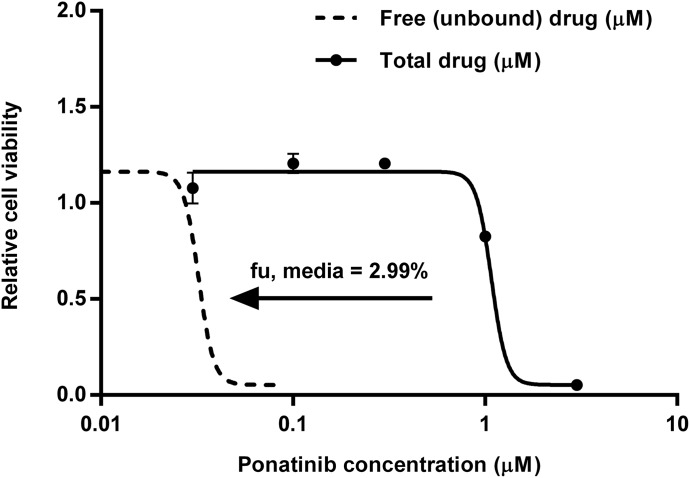

Free drug concentrations were calculated by multiplying the total drug concentrations that were measured using LC-MS/MS by the corresponding fu values that were determined using in vitro binding assay (Liu et al., 2008). The total drug concentration-response curve resulting from in vitro cytotoxic assay was multiplied by the free fraction in serum-containing media (fu,media) to yield the free drug concentration-response curve. Total and free concentration-response curves were used to calculate total IC50 and free IC50, respectively. The in vitro IC50 values were compared with the in vivo drug concentrations, assuming that the IC50 could serve as a hypothetical effective concentration to help explain the differences in response between flank tumor versus brain or different regions of intracranial tumor.

Pharmacokinetic Data Analysis.

Plasma and brain concentration-over-time profiles from a single oral dose in FVB mice were analyzed using Phoenix WinNonlin version 6.4 (Certara USA, Inc., Princeton, NJ). The areas under the curve (AUCs) of brain and plasma concentrations were calculated by performing noncompartmental analysis. Log-linear trapezoidal integration was used to either the last time point [AUC(0–t)] or time infinity [AUC(0–∞)] by including the extrapolated area beyond the last measured concentration. The area extrapolation was calculated by dividing the last measured concentration (Clast) by the terminal rate constant (λ) that describes the last three to five data points in the concentration profiles (Oberoi et al., 2013). Phoenix’s noncompartmental analysis module also reported other parameters/metrics, such as apparent clearance (CL/F), apparent volume of distribution (Vd/F), half-life, and Cmax. The brain-to-plasma ratio (Kp or Kp,uu) was calculated by two methods: 1) the ratio of AUC(0-∞,brain) to AUC(0-∞,plasma), and 2) the ratio of maximum brain concentration (Cmax,brain) to the corresponding plasma concentration at that time point. A previous publication discussed that a transient steady state occurs at the time of Cmax,brain (Tmax,brain), as the rate of change of the brain concentration is zero at that time (Oberoi et al., 2013).

Statistical Analysis.

In vitro IC50 values were estimated by four-parameter nonlinear regression to characterize a log-transformed drug concentration-response curve. The mean estimated free fraction was compared between specimens using repeated unpaired two-sample t tests. Median survival and tumor progression beyond 1,500 mm3 (time to endpoint) were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. The Kp and Kp,uu values were compared with a hypothetical value of 1 (unity) by performing one-sample t tests. In addition, the total and free drug concentrations resulting from tumor distribution studies were compared with the total and free in vitro IC50 values using one-sample t tests. Data presentation and statistical tests were completed using GraphPad Prism (version 6; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). All experimental data are presented as the mean ± S.D. or S.E.M. Based on our previous experience, sample sizes were estimated to obtain approximately 80% power to detect 50% difference between groups. In all cases, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In Vitro Efficacy of Ponatinib in GBM6 Tumor Cells.

The total IC50 value based on the experimental total drug concentration-response curve was 1.08 µM in GBM6 cell culture (Fig. 1). The free fraction of ponatinib was determined in the serum-containing medium using rapid equilibrium dialysis. After adjustment to the free drug concentration-response profile, the free IC50 value was 0.032 µM (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

In vitro efficacy of ponatinib. Growth curve showing effect of various concentrations of ponatinib on GBM6 cells in vitro as determined by CyQUANT assay. The IC50 value resulting from response curves for the experimental total drug concentration (solid line, presented as the mean ± S.E.M; N = 3 in triplicate) or free drug concentration (dotted line, determined using the measured free fraction in serum-containing media). The total and free IC50 values were 1.08 and 0.032 µM, respectively, in GBM6 cell culture.

In Vivo Efficacy of Ponatinib in Flank and Orthotopic GBM6 Xenografts.

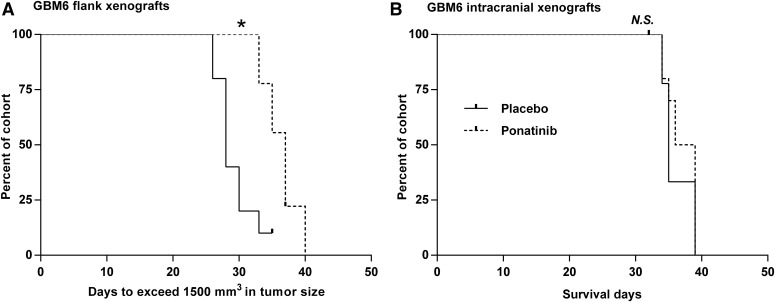

The efficacy of ponatinib was initially evaluated in flank GBM6 tumor models to avoid the potential confounding influence of drug delivery across the BBB. Ponatinib (30 mg/kg/day via oral gavage) significantly prolonged the time to the tumor growth endpoint (progression beyond 1,500 mm3) in GBM6 flank xenografts (37 days vs. 28 days, P = 0.0018; Fig. 2A). Results from this study in the flank tumor model suggested that ponatinib was modestly effective in the GBM model in vivo. We then tested the efficacy of the same ponatinib regimen in the orthotopic model. Interestingly, unlike the tumor stasis observed in flank xenografts, ponatinib was inefficacious in improving the median survival (37.5 vs. 35 days, P = 0.42; Fig. 2B) in the orthotopic model. These results indicate that ponatinib was effective in heterotopic but not in orthotopic GBM6 PDX tumors. The ponatinib treatment did not result in a significant weight loss in the flank and orthotopic GBM6 xenografts (Supplemental Fig. 1). The body weights stayed within 20% of the baseline value until the day of euthanasia, regardless of the treatment (placebo or ponatinib) group.

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of in vivo efficacy of ponatinib (30 mg/kg/day) in GBM6 xenografts. (A) Kaplan-Meier curves for GBM6 flank xenografts (N = 9–10) with the endpoint of tumor size exceeding 1,500 mm3 (*P < 0.05). (B) Kaplan-Meier curves for GBM6 intracranial xenografts (N = 8–10) showing no difference in survival between placebo and ponatinib groups (P > 0.05; N.S., not significant).

Brain Distribution of Ponatinib.

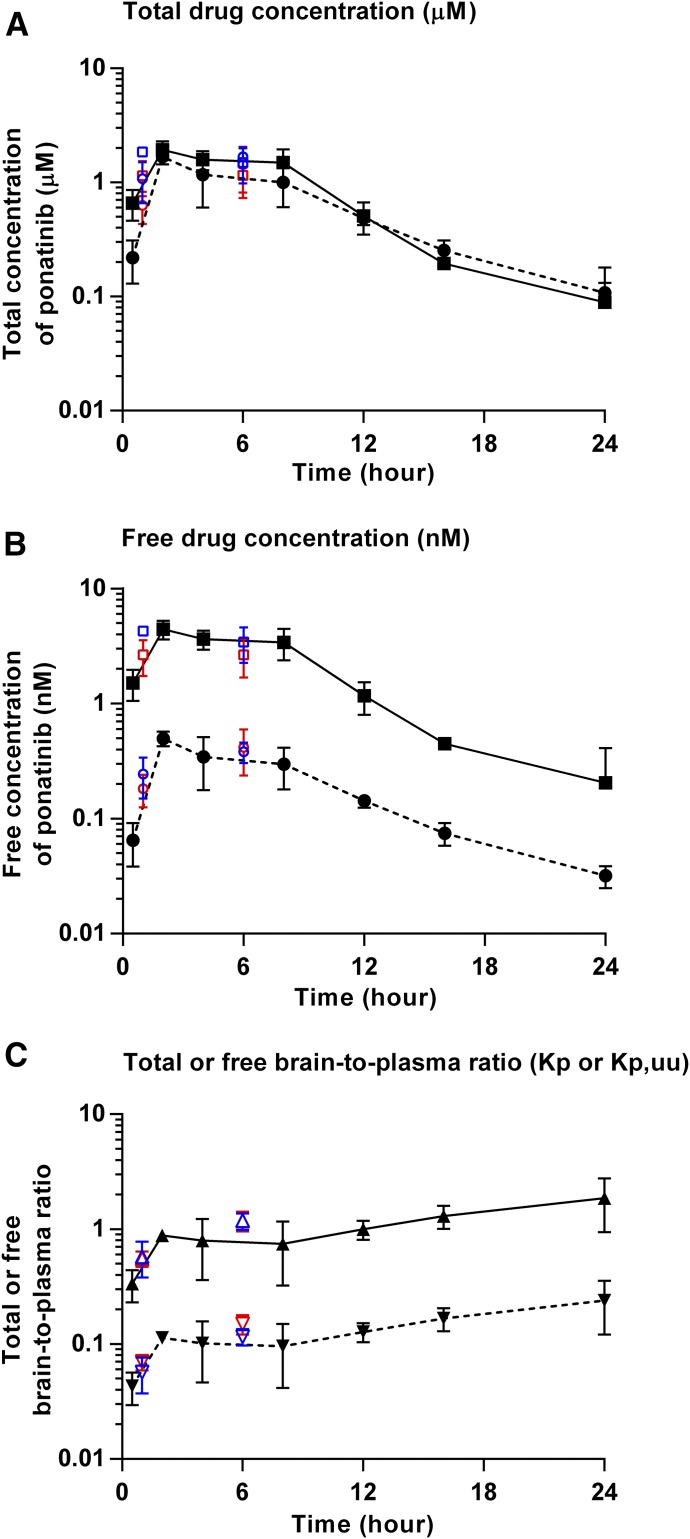

The brain and plasma concentrations and brain-to-plasma ratio profiles after a single oral dose (30 mg/kg) of ponatinib in FVB wild-type, GBM6 flank, and intracranial xenografts are presented in Fig. 3. The brain and plasma concentrations and brain-to-plasma ratios estimated in tumor-bearing animals at 1- and 6-hour time points agreed with the time-course profile determined in FVB mice, indicating a lack of significant difference in the concentrations and estimates of brain-to-plasma ratios, regardless of the mouse strain. As shown in Fig. 3A, the total drug concentrations were lower in the brain than plasma up to 12 hours postdose. However, the total brain drug concentrations were similar to the total plasma concentrations during the last two time points (16 and 24 hours postdose). The maximum concentration of ponatinib occurred at 2 hours postdose both in the brain and plasma. The apparent volume of distribution (Vd/F) was 17.6 l/kg, and the apparent clearance (CL/F) was 46.6 ml/min/kg, as shown in Table 1. The Kp values determined from the AUC ratios [AUC(0–∞,brain)/AUC(0–∞,plasma) or AUC(0–t,brain)/AUC(0–t, plasma)] were about 0.8, and the value was similar regardless of using AUC(0–t) or AUC(0–∞) given the low percentage (<6%) extrapolated from the last measured time point to infinity for the calculation of AUC. The transient steady-state brain-to-plasma ratio (Kp) was 0.87, which closely matched the AUC ratio–based Kp values. In Fig. 3B, the free plasma concentrations were consistently greater than the free brain concentrations throughout all time points after administration of a single oral dose of ponatinib. The Kp,uu values based on AUC(0–∞) or transient steady-state concentrations were about 0.1, which was considerably below unity (1) (Table 1). Such Kp,uu values indicate restricted brain penetration of ponatinib across the BBB. Figure 3C shows the time course of instantaneous Kp and Kp,uu values. The Kp values increased up to 2 hours postdose and stayed consistently around 1 throughout the remaining time points. However, the Kp,uu values stayed below 1 throughout all time points.

Fig. 3.

Pharmacokinetic profiles after administration of a single oral dose (30 mg/kg) of ponatinib in FVB wild-type mice, GBM6 flank, and intracranial xenografts. (A) Total brain (dotted line with circle) and plasma (solid line with square) concentration-over-time curves. (B) Free brain (dotted line with circle) and plasma (solid line with square) concentration-over-time curves. (C) Total brain-to-plasma ratio (Kp; solid line with triangle) and free brain-to-plasma ratio (Kp,uu; dotted line with upside-down triangle). Data are presented as the mean ± S.D. The data in FVB wild-type mice are displayed in black, those in GBM6 flank xenografts in red, and GBM6 intracranial xenografts in blue.

TABLE 1.

Pharmacokinetic/metric parameters determined by noncompartmental analysis of total and free drug concentrations in the brain and plasma following serial sacrifice (destructive sampling) after a single oral dose (30 mg/kg) of ponatinib in FVB wild-type mice

Data are presented as the mean or mean ± S.E.M.

| Plasma |

Brain |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free Drug | Total Drug | Free Drug | Total Drug | |

| Half-life (h) | — | 4.4 | — | 5.7 |

| Tmax (h) | — | 2 | — | 2 |

| Cmax (µM) (mean ± S.E.M.) | 0.0044 ± 0.00041 | 1.93 ± 0.18 | 0.00050 ± 0.000036 | 1.69 ± 0.12 |

| AUC(0–t) (h × µM) (mean ± S.E.M.) | 0.042 ± 0.0026 | 18.3 ± 1.13 | 0.0043 ± 0.00035 | 14.6 ± 1.21 |

| AUC(0–∞) (h × µM) | 0.043 | 18.9 | 0.0046 | 15.5 |

| Vd/F (l/kg) | — | 17.6 | — | — |

| CL/F (ml/min/kg) | — | 46.6 | — | — |

| Kp [AUC(0–∞) ratio] | — | — | — | 0.82 |

| Kp,uu [AUC(0–∞) ratio] | — | — | 0.11 | — |

| Kp (transient steady state) | — | — | — | 0.87 |

| Kp,uu (transient steady state) | — | — | 0.11 | — |

AUC(0-∞), area under the curve from zero to time infinity; CL/F, apparent clearance; Cmax, maximum drug concentration; Kp (AUC ratio), the ratio of AUC(0-∞,brain) to AUC(0-∞,plasma) using total drug concentrations; Kp (transient steady state), the ratio of the maximum total brain concentration to the corresponding total plasma concentration at that time; Kp,uu (AUC ratio), the ratio of AUC(0-∞,brain) to AUC(0-∞,plasma) using free drug concentrations; Kp,uu (transient steady state), the ratio of the maximum free brain concentration to the corresponding free plasma concentration at that time; Tmax, time at the maximum drug concentration; Vd/F, apparent volume of distribution.

Drug Binding at Various Tissue Sites.

An incubation time of 4 hours was adequate to reach equilibrium between the buffer and sample chambers during the RED experiment. We observed that there was no difference in the estimated free fraction (fu) after 4 hours versus 6 hours of incubation, indicating that equilibrium was reached at 4 hours. Due to the limited tissue quantity available for intracranial tumor, the free fraction of ponatinib in the intracranial tumor was estimated using an incubation time of 4 hours.

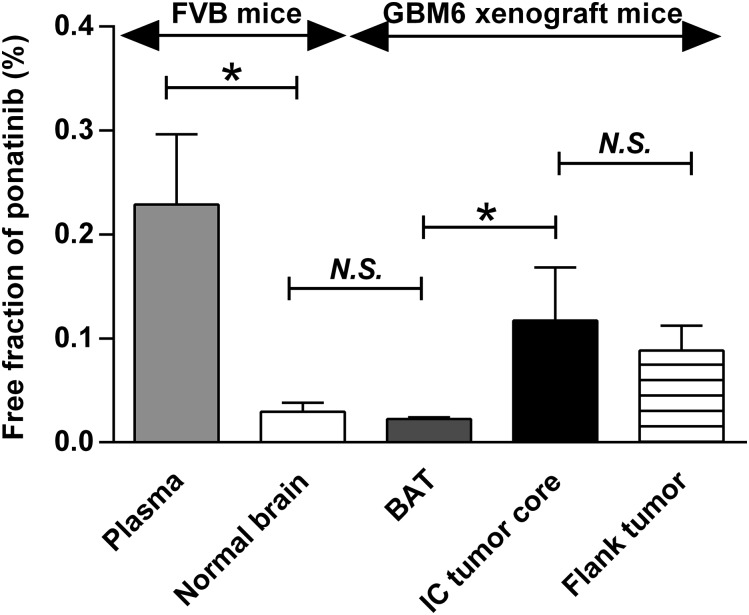

The free fraction of ponatinib in different regions of tumor-bearing brain was evaluated using the specimens collected from tdTomato-guided dissection of tumor regions, as illustrated in Fig. 4. The data resulting from the in vitro binding assay are displayed in Fig. 5 and Table 2. All specimens had a free fraction of less than 1%. Notably, the free fraction in plasma was about 10-fold higher than normal brain (P = 0.0071). The BAT showed the similar free fraction as normal brain (P = 0.24). However, the intracranial tumor core showed a 5-fold higher free fraction than the BAT (P = 0.032), suggesting heterogeneous drug-tissue binding across different regions of the intracranial tumor-bearing brain. Interestingly, the free fraction was similar between flank tumor and intracranial tumor core (P = 0.42).

Fig. 5.

Free fraction (fu) values determined from in vitro RED experiment after 4-hour incubation in triplicate. Two-sample t test was performed to compare plasma versus normal brain (*P < 0.05), normal brain versus BAT (P > 0.05; N.S., not significant), intracranial tumor core (IC tumor core) versus BAT (*P < 0.05), and IC core versus flank tumor (P > 0.05). Data are presented as the mean ± S.D.

TABLE 2.

Free fraction (fu) values determined from in vitro RED experiment after 4-hour incubation in triplicate

Data are presented as the mean ± S.D.

| Matrix |

fu Value (Mean ± S.D.) |

|---|---|

| % | |

| Serum-containing media | 2.99 ± 0.089 |

| Plasma | 0.23 ± 0.068 |

| Normal brain | 0.029 ± 0.0085 |

| BAT | 0.023 ± 0.0014 |

| Intracranial tumor core | 0.12 ± 0.051 |

| Flank tumor | 0.088 ± 0.024 |

Site-Differential Drug Distribution.

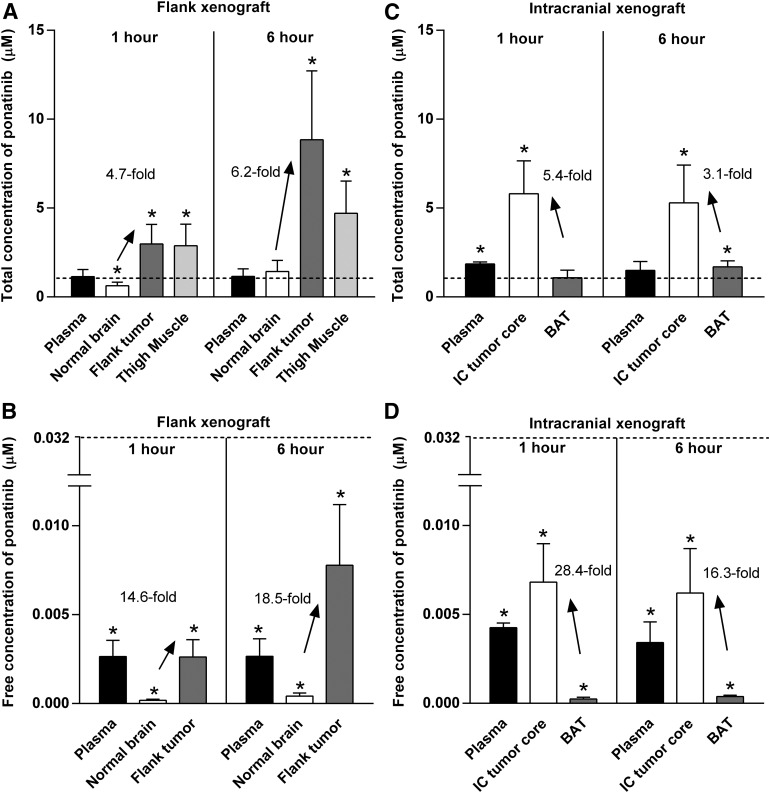

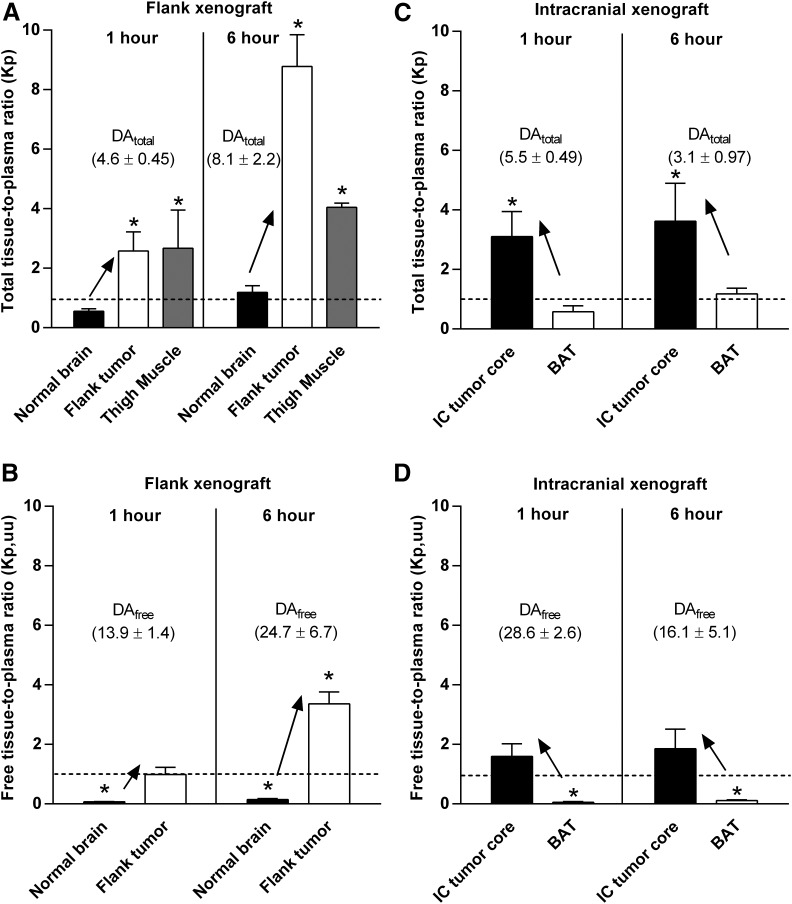

Total and free drug distribution in different regions of tumor-bearing brain was also examined using the specimens collected from tdTomato-guided dissection of tumor regions, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Total and free drug concentrations resulting from the tumor site–specific drug distribution studies are presented in Fig. 6 and Supplemental Table 1. In GBM6 flank xenografts, there were greater total and free drug exposure in flank tumor than the non–tumor-bearing (normal) brain at two different time points. The total and free concentrations were consistently higher in flank tumor compared with normal brain at both 1 and 6 hours, respectively, after administration of a single dose of ponatinib (30 mg/kg) to mice with flank xenografts (Fig. 6, A and B). The total concentration of ponatinib in noncancerous thigh muscle was significantly higher than in normal brain at both 1- and 6-hour time points (Fig. 6A). At the 6-hour time point, however, the total concentration in the noncancerous thigh muscle was lower than the flank tumor, indicating that ponatinib distribution is different between the cancerous and noncancerous peripheral tissues, as may be anticipated by anatomic differences in vessel structure and function related to tumor-induced angiogenic processes. The total and free tissue partition coefficients (Kp and Kp,uu) were at least 4-fold higher in flank tumor than the normal brain (Fig. 7, A and B; Supplemental Table 1) as reflected in the DAtotal and DAfree values, respectively, demonstrating limited drug delivery to the brain compared with flank tumor. The Kp value was greater than 1 (circa 2.6–8.8) in the flank tumor and noncancerous thigh muscle (circa 2.7–4.0), but less than or equal to 1 in the normal brain (circa 0.6–1.2) at both time points (1 and 6 hours postdose). The Kp,uu value was consistently and significantly less than 1 for normal brain at both time points, whereas the Kp,uu value in the flank tumor equaled or exceeded unity (1) (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 6.

Concentrations of ponatinib at 1 and 6 hours after administration of a single oral dose (30 mg/kg) of ponatinib in GBM6 flank and intracranial xenograft mice in tumor distribution studies. (A) Total drug concentration in plasma, normal brain, flank tumor, and thigh muscle (noncancerous) in flank xenograft mice (N = 4–6). (B) Free drug concentration in plasma, normal brain, and flank tumor in flank xenograft mice (N = 4–6). Total drug concentration (C) and free drug concentration (D) in plasma, intracranial tumor core (IC tumor core), and BAT in intracranial xenograft mice (N = 3–4). Dotted lines represent hypothetical effective concentrations, or IC50 values (1.08 µM based on total drug and 0.032 µM based on free drug). One-sample t tests were performed to compare the total and free concentrations with the respective total and free IC50 values at a significance level of 0.05 (*P < 0.05). The upward arrows and the listed values indicate the higher drug concentrations in the flank tumor versus normal brain in the flank xenograft mice, and those in the IC tumor core versus BAT in the intracranial xenograft mice. Data are presented as the mean ± S.D.

Fig. 7.

Total and free tissue-to-plasma ratios (single time point Kp and Kp,uu, respectively) at 1 and 6 hours after administration of a single oral dose (30 mg/kg) of ponatinib in GBM6 flank and intracranial xenograft mice for tumor distribution studies. (A) Kp in normal brain, flank tumor, and thigh muscle (noncancerous) in flank xenograft mice (N = 4–6). (B) Kp,uu in normal brain and flank tumor in flank xenograft mice (N = 4–6). Kp (C) and Kp,uu (D) in the intracranial tumor core (IC tumor core) and BAT in intracranial xenograft mice (N = 3–4). One-sample t tests were performed to compare the experimental values of tissue partition coefficients (Kp and Kp,uu) with the hypothetical value of 1 at a significance level of 0.05 (*P < 0.05). Dotted lines represent unity (Kp or Kp,uu at 1). The upward arrows and the listed DA values (DAtotal or DAfree) indicate the higher tissue partition coefficients (Kp or Kp,uu) in the flank tumor versus normal brain in the flank xenograft mice, and those in the IC tumor core versus BAT in the intracranial xenograft mice. Data are presented as the mean ± S.D.

In GBM6 intracranial xenografts, regional differences in total and free drug concentrations were observed between the intracranial tumor core and BAT. The total and free drug concentrations were consistently higher in tumor core versus BAT after 1 and 6 hours, respectively, of ponatinib treatment (Fig. 6, C and D; Supplemental Table 1). The intracranial tumor core had at least 3-fold higher total and free tissue partition coefficients (Kp and Kp,uu) than BAT at both time points (Fig. 7, C and D; Supplemental Table 1). As reflected in the DAtotal and DAfree values in these regions, the growing edge of intracranial tumor (BAT) has relatively impeded drug accumulation compared with the necrotic core of intracranial tumor.

The total and free drug concentrations resulting from drug distribution studies were compared with the total and free IC50 values, respectively. The total concentrations in flank tumor exceeded the total IC50 value at least by 2.5-fold at 1 and 6 hours, respectively, after ponatinib treatment, whereas those in the normal brain did not (Fig. 6A; Supplemental Table 1). These data suggest that drug distribution to normal brain is disadvantaged. In the intracranial xenografts, the total drug concentration in the intracranial tumor core exceeded the total IC50 value at both time points, but did not in the BAT (Fig. 6C; Supplemental Table 1), indicating regional differences in drug accumulation in the intracranial tumor. The relative differences in drug concentrations and the total IC50 value in the tissue sites were consistent with the contrasted efficacy between flank versus orthotopic models. However, in vitro free IC50 was not reached even with the maximum tolerated dose of ponatinib (30 mg/kg/day) (Fig. 6, B and D).

Discussion

We have previously reported differences in the distribution of small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors between flank and orthotopic tumor sites, which resulted in variable treatment efficacy in PDX GBM models (Parrish et al., 2015; Pokorny et al., 2015). These studies showed the link between limited drug distribution to the brain and lack of efficacy in orthotopic tumors. The current study showed a similar finding for ponatinib, and further indicated that various regions of the brain and brain tumor, i.e., the normal brain (contralateral hemisphere) and the invasive rim of an intracranial tumor (BAT), have variable and limited total (i.e., free and bound) drug distribution. Importantly, these data also revealed that these intracranial regions had lower levels of free drug exposure compared with the flank tumor, despite a relatively high total brain-to-plasma partition coefficient (Kp) near unity.

The free drug concentration in plasma is considered to be a driving force for distributional processes, including distribution to the brain, according to the free drug hypothesis (Dubey et al., 1989; Hammarlund-Udenaes et al., 2008; de Lange, 2013). Brain drug penetration is modulated by the BBB, where tight junctions prevent paracellular drug transport and efflux transporters reduce drug accumulation in the brain (Abbott et al., 2006). However, this vascular barrier is quite different in the peripheral vasculature, and greater drug penetration to a flank tumor versus intracranial tumor for a tyrosine kinase inhibitor has been reported (Parrish et al., 2015). If the AUCs of free drug in the brain and plasma were equal, the observed Kp,uu would be 1, indicating the absence of net transporter-mediated drug flux and that passive diffusion is possibly the only transport process at the BBB. This situation may result in similar free brain concentration and free plasma concentration profiles. In the current study, the Kp,uu value for ponatinib, however, was significantly below 1 in the normal brain and the invasive rim (BAT) of intracranial tumor (Fig. 7), indicating that active efflux transport modulates the ponatinib accumulation in the brain. It is important to note that the assessment of brain penetration using a total brain-to-plasma ratio (Kp) can be misleading for a compound, such as ponatinib, because the Kp value does not account for free drug concentration ratios across the BBB, where efflux transporters can lead to a greater clearance out of, rather than into, the brain. These free plasma and brain concentration data (Fig. 3), and the resultant Kp,uu, suggest that efflux transport strongly influences ponatinib brain penetration. This finding was not surprising, since we have previously shown that ponatinib is a substrate of the two major efflux transporters in the BBB, breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp) and P-glycoprotein (P-gp/Mdr1). In studies examining the brain distribution of ponatinib in wild-type and transporter-deficient mice, the brain-to-plasma Kp value for total drug was 18-fold higher in the Mdr1a/b(−/−)Bcrp1(−/−) mice lacking Bcrp and P-glycoprotein compared with wild-type (Laramy et al., 2015, 2016).

The extent of free drug fraction at the site of action is anticipated to differ depending on the tissue composition. The study by Ha et al. (2007) demonstrated that the lipid composition differs between tumor tissues obtained from flank and orthotopic implantation in NOD.CB17-Prkdcscid/J (NOD/Scid) mice based on a lipidomic analysis for two human GBM xenograft lines (GBM10 and GBM43 from the Mayo Clinic GBM PDX panel). This finding suggests that, even for the same tumor xenograft, different tissue-dependent microenvironments can result in widely varying free fractions of a drug. Our in vitro binding assay demonstrated differences in the free drug fraction between the two tumor sites, where the free fraction was about 4-fold higher in the flank tumor environment than the invasive growing edge of the intracranial tumor environment. Our finding is consistent with the theory that different tissue compositions can influence the free fraction and, hence, free drug exposure at the site of action (tumor). If the brain-to-plasma partitioning of total drug (in the case of ponatinib, Kp ∼ 1) is the only parameter used for the assessment of brain penetration, it is possible to erroneously conclude that drug exposure is not an issue in the lack of efficacy in orthotopic GBM. The current study showed that the free fraction of ponatinib was about 10-fold lower in the invasive BAT region (and normal brain) than plasma. Solely due to the different free fractions between plasma and brain, the Kp,uu between brain and plasma became 0.1, whereas the Kp value reached unity. The Kp,uu below unity was also expected because ponatinib is a substrate of the two major efflux transporters in the BBB (Laramy et al., 2015, 2016). The Kp,uu between flank tumor (or intracranial tumor core) and plasma equaled or exceeded unity at 1 and 6 hours postdose, whereas the Kp,uu stayed below unity in the growing edge of the tumor (BAT), i.e., the desired site of action. The compromised free drug exposure in the brain compared with flank tumor may account for the differences in efficacy between the flank and orthotopic tumors. This may be an important consideration when conducting in vivo screening for efficacy of antitumor therapies for brain tumors. The tissue-dependent composition and binding highlight that the tumor implantation to two sites (e.g., flank and orthotopic) allows not only exploration of the influence of different tumor sites on efficacy testing, but also drug delivery issues that have therapeutic consequences, such as a different free fractions in various tumor microenvironments.

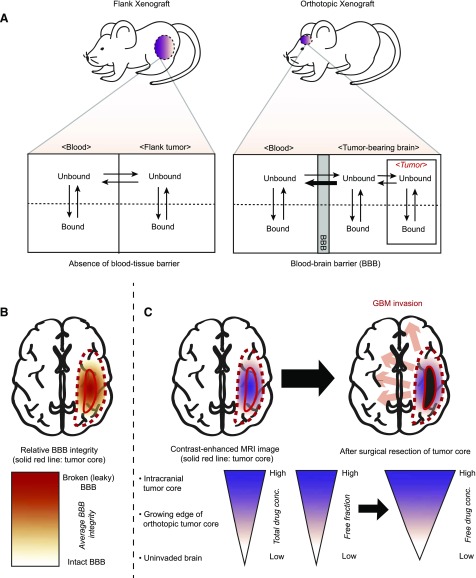

The use of heterotopic and orthotopic GBM models within a single study was useful in investigating differences in free fraction and site-dependent drug delivery. A greater therapeutic advantage, in terms of free drug exposure, was observed in flank tumor than in orthotopic tumor, in part because the efflux or blood-tissue barrier is absent in the flank tumor unlike the orthotopic tumor. Figure 8A shows a hypothetical schematic of the equilibration of free (unbound) drugs across different tissue compartments, including blood, flank, and orthotopic tumors. Orthotopic GBM tumor models have distinctive disadvantages to effective therapy because of the heterogeneity in the BBB vasculature. Angiogenesis, often accompanying dissemination of glioblastoma invasion, causes a focal disruption of the BBB (Jain et al., 2007; Claes et al., 2008). As a result, the BBB vasculature is relatively leakier in the core region in contrast to the brain parenchyma, which is farther away from the necrotic tumor core (Youland et al., 2013) (Fig. 8B). The BAT, or the growing edge region of intracranial tumor, is the therapeutically critical area that requires “adequate” free drug exposure to enhance efficacy of invasive GBM. This particular area is not visualized by contrast-enhanced imaging and, thus, is not removed by the imaging-guided surgical resection of the necrotic core (Agarwal et al., 2011; Youland et al., 2013). The lower Kp,uu and free drug concentration of ponatinib in the BAT than the intracranial tumor core suggest that intact BBB may reduce the penetration of ponatinib into the growing edge and thus allow GBM invasion throughout the rest of the brain (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

A hypothetical schematic of the equilibration of free (unbound) drug delivery between plasma (blood) and tumor sites (flank or orthotopic tumor). (A) The movement of free drugs in the absence of the blood-tissue barrier in PDX mice with flank xenograft and in the presence of the BBB in PDX mice with orthotopic xenograft. (B) Relative BBB integrity throughout the brain bearing GBM tumor. (C) Relatively restricted free drug delivery to the growing edge (BAT) of orthotopic tumor and resultant GBM invasion throughout the rest of the brain. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

The present study showed that regional differences in total and free drug exposure in the brain or across different regions of an intracranial tumor may negatively affect efficacy in an orthotopic model. The free concentration of ponatinib was lower in the invasive rim of intracranial tumor and normal brain compared with flank tumor and brain tumor core. The assessment of Kp,uu also revealed the potential influence of transporter-mediated drug efflux on ponatinib CNS delivery, confirmed by transporter-deficient mouse models. The free fraction of ponatinib was variable at various tumor sites, suggesting that differences in the tumor or tissue microenvironment, i.e., the composition of a binding matrix, can influence efficacy through spatial heterogeneity in active (free) drug exposure.

A limitation of the present study is that the in vitro IC50 value was notably above the in vivo free concentration of ponatinib in flank tumor, leading to in vitro–in vivo discrepancies in predicting the site-dependent efficacy. A possible explanation is that the estimation of free fraction in the serum-containing media (used for scaling total IC50 to free IC50) might have been overestimated, perhaps, due to other nonspecific binding (e.g., cell culture apparatus) and complex in vivo processes (e.g., metabolism and other cellular processes) that can further sequester free drug. It is also possible that inclusion of additional data points in the response region of the drug concentration-time curve could have improved the estimation of the IC50.

In conclusion, this study showed that there was a significant difference in the flank versus orthotopic efficacy of the multitargeted kinase inhibitor ponatinib against a GBM PDX that exhibited resistance to standard therapy. Despite the apparent high brain penetration of ponatinib based on the total drug concentrations and AUC ratio (Kp), the AUC ratio of free drug (Kp,uu) between brain and plasma was significantly less than unity when free fractions were used to determine the partitioning of free drug. The Kp,uu of brain below unity can indicate a net efflux process out of the brain. Importantly, this free Kp,uu varied among tumor sites (brain vs. flank) and even within a tumor site (core vs. BAT). The tumor microenvironment and site-dependent variability in drug-tissue binding may account for the lower, free (active) drug exposure in the BAT, the critical site of action for effective GBM treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jim Fisher, Clinical Pharmacology Analytical Laboratory, University of Minnesota, for his support in the development of the LC-MS/MS assay.

Abbreviations

- AUC

area under the curve

- BAT

brain-around-tumor

- BBB

blood-brain barrier

- DA

distribution advantage

- FVB

Friend leukemia virus strain B

- GBM

glioblastoma

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry

- PDX

patient-derived xenograft

- RED

rapid equilibrium dialysis

- tdT

tandem tomato

- TMZ

temozolomide

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Laramy, Gupta, Ma, Parrish, Sarkaria, Elmquist.

Conducted experiments: Laramy, Kim, Parrish, Gupta, Mladek, Bakken, Carlson.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Laramy, Zhang.

Performed data analysis: Laramy, Parrish, Sarkaria, Elmquist.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Laramy, Parrish, Kim, Gupta, Sarkaria, Elmquist.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grants R01 CA138437, R01 NS077921, U54 CA210180, and P50 CA108961]. J.K.L. was supported by the Edward G. Rippie, Rory P. Remmel and Cheryl L. Zimmerman in Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics, and American Foundation for Pharmaceutical Education Pre-Doctoral Fellowships.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

This article has supplemental material available at jpet.aspetjournals.org.

References

- Abbott NJ, Rönnbäck L, Hansson E. (2006) Astrocyte-endothelial interactions at the blood-brain barrier. Nat Rev Neurosci 7:41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal S, Sane R, Oberoi R, Ohlfest JR, Elmquist WF. (2011) Delivery of molecularly targeted therapy to malignant glioma, a disease of the whole brain. Expert Rev Mol Med 13:e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan CW, Verhaak RG, McKenna A, Campos B, Noushmehr H, Salama SR, Zheng S, Chakravarty D, Sanborn JZ, Berman SH, et al. TCGA Research Network (2013) The somatic genomic landscape of glioblastoma. Cell 155:462–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson BL, Pokorny JL, Schroeder MA, Sarkaria JN. (2011) Establishment, maintenance and in vitro and in vivo applications of primary human glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) xenograft models for translational biology studies and drug discovery. Curr Protoc Pharmacol Chapter 14:Unit 14.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cen L, Carlson BL, Pokorny JL, Mladek AC, Grogan PT, Schroeder MA, Decker PA, Anderson SK, Giannini C, Wu W, et al. (2013) Efficacy of protracted temozolomide dosing is limited in MGMT unmethylated GBM xenograft models. Neuro-oncol 15:735–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claes A, Wesseling P, Jeuken J, Maass C, Heerschap A, Leenders WP. (2008) Antiangiogenic compounds interfere with chemotherapy of brain tumors due to vessel normalization. Mol Cancer Ther 7:71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo I, Vital AL, Gonzalez-Tablas M, Patino MdelC, Otero A, Lopes MC, de Oliveira C, Domingues P, Orfao A, Tabernero MD. (2015) Molecular and genomic alterations in glioblastoma multiforme. Am J Pathol 185:1820–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange EC. (2013) The mastermind approach to CNS drug therapy: translational prediction of human brain distribution, target site kinetics, and therapeutic effects. Fluids Barriers CNS 10:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaud C, Westwood JA, John LB, Flynn JK, Paquet-Fifield S, Duong CP, Yong CS, Pegram HJ, Stacker SA, Achen MG, et al. (2014) Tissues in different anatomical sites can sculpt and vary the tumor microenvironment to affect responses to therapy. Mol Ther 22:18–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey RK, McAllister CB, Inoue M, Wilkinson GR. (1989) Plasma binding and transport of diazepam across the blood-brain barrier. No evidence for in vivo enhanced dissociation. J Clin Invest 84:1155–1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Medicines Agency (2013) Iclusig: CHMP Assessment Report (EMA/CHMP/220290/2013). Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use, CHMP, London. [Google Scholar]

- Fridén M, Gupta A, Antonsson M, Bredberg U, Hammarlund-Udenaes M. (2007) In vitro methods for estimating unbound drug concentrations in the brain interstitial and intracellular fluids. Drug Metab Dispos 35:1711–1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini C, Sarkaria JN, Saito A, Uhm JH, Galanis E, Carlson BL, Schroeder MA, James CD. (2005) Patient tumor EGFR and PDGFRA gene amplifications retained in an invasive intracranial xenograft model of glioblastoma multiforme. Neuro-oncol 7:164–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta SK, Mladek AC, Carlson BL, Boakye-Agyeman F, Bakken KK, Kizilbash SH, Schroeder MA, Reid J, Sarkaria JN. (2014) Discordant in vitro and in vivo chemopotentiating effects of the PARP inhibitor veliparib in temozolomide-sensitive versus -resistant glioblastoma multiforme xenografts. Clin Cancer Res 20:3730–3741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha SJ, Showalter G, Cai S, Wang H, Liu WM, Cohen-Gadol AA, Sarkaria JN, Rickus J, Springer J, Adamec J, et al. (2007) Lipidomic analysis of glioblastoma multiforme using mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 79:8423–8430.17929901 [Google Scholar]

- Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Fridén M, Syvänen S, Gupta A. (2008) On the rate and extent of drug delivery to the brain. Pharm Res 25:1737–1750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WS, Metcalf CA, Sundaramoorthi R, Wang Y, Zou D, Thomas RM, Zhu X, Cai L, Wen D, Liu S, et al. (2010) Discovery of 3-[2-(imidazo[1,2-b]pyridazin-3-yl)ethynyl]-4-methyl-N-4-[(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)methyl]-3-(trifluoromethyl)phenylbenzamide (AP24534), a potent, orally active pan-inhibitor of breakpoint cluster region-abelson (BCR-ABL) kinase including the T315I gatekeeper mutant. J Med Chem 53:4701–4719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain RK, di Tomaso E, Duda DG, Loeffler JS, Sorensen AG, Batchelor TT. (2007) Angiogenesis in brain tumours. Nat Rev Neurosci 8:610–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalvass JC, Maurer TS. (2002) Influence of nonspecific brain and plasma binding on CNS exposure: implications for rational drug discovery. Biopharm Drug Dispos 23:327–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laramy JK, Parrish KE, and Elmquist WF (2016) Influence of efflux transporters on the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of ponatinib, a multi-kinase inhibitor, in Poster presentation at the 2016 American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists (AAPS) Annual Meeting and Exposition; 2016 Nov 13-17; Denver, Colorado. Poster 07T0400. [Google Scholar]

- Laramy JK, Parrish KE, Zhang S, Bakken K, Carlson BL, Mladek A, Ma D, Sarkaria J, and Elmquist W(2015) Brain Distribution of Ponatinib, a Multi-kinase Inhibitor: Implications for the Treatment of Malignant Brain Tumors. Poster presentation at the 2015 American Association of Pharmaceutical Scientists (AAPS) Annual Meeting and Exposition; October 25-29, 2015; Orlando, Florida. Poster W4339. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Chen C, Smith BJ. (2008) Progress in brain penetration evaluation in drug discovery and development. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 325:349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minniti G, Muni R, Lanzetta G, Marchetti P, Enrici RM. (2009) Chemotherapy for glioblastoma: current treatment and future perspectives for cytotoxic and targeted agents. Anticancer Res 29:5171–5184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberoi RK, Mittapalli RK, Elmquist WF. (2013) Pharmacokinetic assessment of efflux transport in sunitinib distribution to the brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 347:755–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberoi RK, Parrish KE, Sio TT, Mittapalli RK, Elmquist WF, Sarkaria JN. (2016) Strategies to improve delivery of anticancer drugs across the blood-brain barrier to treat glioblastoma. Neuro-oncol 18:27–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hare T, Shakespeare WC, Zhu X, Eide CA, Rivera VM, Wang F, Adrian LT, Zhou T, Huang WS, Xu Q, et al. (2009) AP24534, a pan-BCR-ABL inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia, potently inhibits the T315I mutant and overcomes mutation-based resistance. Cancer Cell 16:401–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Xu J, Kromer C, Wolinsky Y, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. (2016) CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2009-2013. Neuro-oncol 18 (Suppl 5):v1–v75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker NR, Khong P, Parkinson JF, Howell VM, Wheeler HR. (2015) Molecular heterogeneity in glioblastoma: potential clinical implications. Front Oncol 5:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrish KE, Pokorny J, Mittapalli RK, Bakken K, Sarkaria JN, Elmquist WF. (2015) Efflux transporters at the blood-brain barrier limit delivery and efficacy of cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitor palbociclib (PD-0332991) in an orthotopic brain tumor model. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 355:264–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel MR, Chang YF, Chen IY, Bachmann MH, Yan X, Contag CH, Gambhir SS. (2010) Longitudinal, noninvasive imaging of T-cell effector function and proliferation in living subjects. Cancer Res 70:10141–10149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazarentzos E, Bivona TG. (2015) Adaptive stress signaling in targeted cancer therapy resistance. Oncogene 34:5599–5606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips HS, Kharbanda S, Chen R, Forrest WF, Soriano RH, Wu TD, Misra A, Nigro JM, Colman H, Soroceanu L, et al. (2006) Molecular subclasses of high-grade glioma predict prognosis, delineate a pattern of disease progression, and resemble stages in neurogenesis. Cancer Cell 9:157–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny JL, Calligaris D, Gupta SK, Iyekegbe DO, Jr, Mueller D, Bakken KK, Carlson BL, Schroeder MA, Evans DL, Lou Z, et al. (2015) The Efficacy of the wee1 inhibitor MK-1775 combined with temozolomide is limited by heterogeneous distribution across the blood-brain barrier in glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res 21:1916–1924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkaria JN, Carlson BL, Schroeder MA, Grogan P, Brown PD, Giannini C, Ballman KV, Kitange GJ, Guha A, Pandita A, et al. (2006) Use of an orthotopic xenograft model for assessing the effect of epidermal growth factor receptor amplification on glioblastoma radiation response. Clin Cancer Res 12:2264–2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkaria JN, Yang L, Grogan PT, Kitange GJ, Carlson BL, Schroeder MA, Galanis E, Giannini C, Wu W, Dinca EB, et al. (2007) Identification of molecular characteristics correlated with glioblastoma sensitivity to EGFR kinase inhibition through use of an intracranial xenograft test panel. Mol Cancer Ther 6:1167–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierra JR, Tsao MS. (2011) c-MET as a potential therapeutic target and biomarker in cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol 3(1, Suppl):S21–S35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaak RG, Hoadley KA, Purdom E, Wang V, Qi Y, Wilkerson MD, Miller CR, Ding L, Golub T, Mesirov JP, et al. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2010) Integrated genomic analysis identifies clinically relevant subtypes of glioblastoma characterized by abnormalities in PDGFRA, IDH1, EGFR, and NF1. Cancer Cell 17:98–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolburg H, Noell S, Fallier-Becker P, Mack AF, Wolburg-Buchholz K. (2012) The disturbed blood-brain barrier in human glioblastoma. Mol Aspects Med 33:579–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youland RS, Kitange GJ, Peterson TE, Pafundi DH, Ramiscal JA, Pokorny JL, Giannini C, Laack NN, Parney IF, Lowe VJ, et al. (2013) The role of LAT1 in (18)F-DOPA uptake in malignant gliomas. J Neurooncol 111:11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]