Abstract

Heart failure is characterized by the inability of the cardiovascular system to maintain oxygen (O2) delivery (i.e., muscle blood flow in non-hypoxemic patients) to meet O2 demands. The resulting increase in fractional O2 extraction can be non-invasively tracked by deoxygenated hemoglobin concentration (deoxi-Hb) as measured by near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS). We aimed to establish a simplified approach to extract deoxi-Hb-based indices of impaired muscle O2 delivery during rapidly-incrementing exercise in heart failure. We continuously probed the right vastus lateralis muscle with continuous-wave NIRS during a ramp-incremental cardiopulmonary exercise test in 10 patients (left ventricular ejection fraction <35%) and 10 age-matched healthy males. Deoxi-Hb is reported as % of total response (onset to peak exercise) in relation to work rate. Patients showed lower maximum exercise capacity and O2 uptake-work rate than controls (P<0.05). The deoxi-Hb response profile as a function of work rate was S-shaped in all subjects, i.e., it presented three distinct phases. Increased muscle deoxygenation in patients compared to controls was demonstrated by: i) a steeper mid-exercise deoxi-Hb-work rate slope (2.2±1.3 vs 1.0±0.3% peak/W, respectively; P<0.05), and ii) late-exercise increase in deoxi-Hb, which contrasted with stable or decreasing deoxi-Hb in all controls. Steeper deoxi-Hb-work rate slope was associated with lower peak work rate in patients (r=–0.73; P=0.01). This simplified approach to deoxi-Hb interpretation might prove useful in clinical settings to quantify impairments in O2 delivery by NIRS during ramp-incremental exercise in individual heart failure patients.

Keywords: Heart failure, Exercise, Oxygen, Muscle, Near-infrared spectroscopy

Introduction

Heart failure is a complex syndrome characterized by the inability of the cardiovascular system to maintain oxygen (O2) delivery [i.e., muscle blood flow (Q̇m)] matched to metabolic demands (1). This is particularly true during dynamic exercise as the peripheral muscle requirements for O2 increase markedly (2,3). In fact, there is well-established evidence that the deleterious bioenergetic consequences (e.g., early anaerobic metabolism) of impaired O2 availability are centrally related to patients' exercise intolerance (4). Selected pharmacological (e.g., sildenafil intake) and non-pharmacological therapies (i.e., physical training) have been found useful in improving Q̇m-O2 uptake (V̇O2) matching with important beneficial consequences to patients functioning (5–7).

In this context, there is a widespread interest in non-invasive methods to detect impairments in exercise Q̇m-V̇O2 matching in heart failure patients (5). Near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), in particular, is an optical method that allows transcutaneous monitoring of skeletal muscle deoxygenation (deoxi-Hb), an index of fractional O2 extraction (8,9). It has been postulated that muscle deoxi-Hb can reflect dynamic abnormalities in Q̇m-V̇O2 coupling when the rate of increase in V̇O2 is constant, e.g., in response to a rapidly-incremental (ramp) exercise protocol. Thus, higher values and/or faster increases in deoxi-Hb would result from insufficient Q̇m relative to V̇O2 as muscle O2 extraction increases to compensate for insufficient O2 delivery (4,10). Despite its potential clinical usefulness, this approach has been mostly used in healthy subjects (4). Moreover, the response profile has been described by complex non-linear mathematical models (either the hyperbolic or sigmoid functions) (4,10). As pointed out by Spencer et al. (11), fitting the whole response in a single function has little physiological rationale and it might represent a “fit of convenience”. Translating the deoxi-Hb signal to the clinical world using a practical and feasible approach remains an important gap to allow a wider use of NIRS for the functional assessment of heart failure patients.

This prospective study was designed to establish a novel, clinically-friendly approach to quantify Q̇m-V̇O2 mismatch by deoxi-Hb during ramp-incremental exercise in patients with heart failure. We specifically hypothesized that impairments in peripheral muscle O2 delivery would be indicated by steeper mid-exercise deoxi-Hb-work rate slope and/or greater increases in late-exercise deoxi-Hb in patients compared to healthy controls.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Ten non-smoking males from the heart failure outpatient clinic of the São Paulo Hospital (New York Heart Association functional score II and III) and 10 age- and gender-matched healthy controls were assessed. Patients presented with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) <35% according to 3-D transthoracic echocardiogram. They were under optimal pharmacological treatment for stage “C” patients as established by the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology guidelines (2). We excluded patients who had a history of recent disease decompensation (within 3 months), functional evidence of obstructive pulmonary disease (forced expiratory volume in 1 s/forced vital capacity <0.7), anemia (hemoglobin <13 g/dL), exercise-induced asthma, diabetes mellitus or other metabolic disease, significant ventricular arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation, unstable angina, acute myocardial infarction in the preceding year, and peripheral arterial disease associated with intermittent claudication. No patient had been previously submitted to cardiovascular rehabilitation to avoid the influence of physical activity on muscle oxygenation (12).

Controls were office staff and non-medical employees from the Universidade Federal de São Paulo. They were required to be sedentary as indicated by lack of regular physical activity in the preceding 5 years. No control presented with a previous history of pulmonary, cardiovascular, autoimmune or metabolic diseases. Prior to study inclusion, the controls underwent clinical assessment, pulmonary function tests, blood analysis (including Hb) and resting electrocardiogram and echocardiogram. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Board and all participants gave written informed consent (Project #0935/07).

Measurements

Cardiopulmonary exercise test

Cycle ergometer-based (Corival® 400, Medical Graphics Corporation, MGC, USA) cardiopulmonary exercise test (CardiO2 system, MGC) was performed following a ramp-incremental protocol (5–10 W/min for patients and 5–20 W/min for controls). Subjects were asked to cycle at a frequency of 50±5 rpm. Peak V̇O2 (mL/min) was the highest value obtained at exercise cessation: values were compared with those predicted by Neder and co-workers (13). Other measurements included: CO2 output (V̇CO2, mL/min), R (respiratory exchange ratio), minute ventilation (V̇E, L/min), respiratory rate (f), ventilatory equivalents for O2 and CO2 (V̇E/V̇O2 e V̇E/V̇CO2) and end-tidal partial pressure of O2 and CO2 (PETO2 e PETCO2, mmHg). Heart rate (HR, bpm) was determined using R-R distance as determined by a 12-lead electrocardiogram (CardioPerfect™, MGC). Oxygen saturation was determined by pulse oximetry (SpO2, Onyx™, Nonim, USA). Patients were asked about their dyspnea and leg effort every 2 min according to the 0-10 Borg scale. The V̇O2 at the lactate threshold was estimated by the gas exchange method (modified V-slope) and confirmed by the ventilatory method, i.e., V̇E/V̇O2 and PETO2 increase coupled with V̇E/V̇CO2 and PETCO2 stability.

Peripheral muscle oxygenation

Leg muscle deoxygenation was measured by the NIRO 200® system (Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan). The NIRS theory has been described elsewhere (9). Briefly, an optical fiber bundle carries the near-infrared light produced by a laser diode to the tissue while another optical fiber bundle captures the tissue-transmitted light to a photon detector in the spectrometer. The light intensity and the transmitted light is continuously recorded and, along with the relevant extinction coefficient, used to measure changes in the hemoglobin oxygenation level (Hb) and myoglobin (Mb). The optodes (light emitting and photoreceptor sensors) were set at the vastus lateralis muscle of the left quadriceps, between the lateral epicondyle and greater trochanter of the femur, fixed with an appropriate adhesive tape and covered with a neoprene band to avoid light penetration.

The variables evaluated by NIRS were oxygenated and deoxygenated Hb concentrations (oxi-Hb and deoxi-Hb, respectively). From these primary signals, total Hb is derived, i.e., oxi-Hb + deoxi-Hb. Considering that about 70% of the Hb intramuscular signal comes from venous bed, variations in local blood volume (including venous) are expected to impact more oxi-Hb than deoxi-Hb (14–16). Thus, many laboratories have adopted deoxi-Hb as the preferred marker for changes in the O2 fractional extraction (14,15,17), i.e., an index of Q̇m-V̇O2 (mis)match (18). The device used here (continuous wave NIRS) does not measure light tissue reflection and scattering (18); thus, values were recorded as a variation (Δ) from baseline in mMol/cm and are reported as a percent of the end-test value, i.e., 0–100%.

Statistical analysis

The statistical program used was SPSS® version 13.0 (SPSS®, USA). Unless otherwise stated, data are reported as means and SD. Unpaired t-test (or Mann-Whitney test, when appropriated) was used for between-group comparisons. The slope of linear regression involving exercise deoxi-Hb as a function of work rate determined the rate of increase in the former variable. Pearson correlation was used to assess the level of linear association between continuous variables. The level of statistical significance was set at <5% (P<0.05) for all tests.

Results

There were no significant between-group differences in anthropometric attributes (Table 1). The main etiology of heart failure was non-ischemic cardiomyopathy and, as expected by the inclusion criteria, all patients showed severe left ventricular dysfunction. Peak work rate and peak V̇O2 were markedly reduced in patients; for instance, 7 patients were on Weber’s class C. Patients had shallower V̇O2-work rate slopes than controls; conversely, V̇E/V̇CO2 was higher and PETCO2 lower in patients compared to controls (P<0.05; Table 1).

Table 1. Resting and exercise characteristics of healthy controls and patients with heart failure.

| Variables | Controls (n=10) | Heart failure (n=10) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic/anthropometric | ||

| Age (year) | 61.5±9.3 | 52.1±11.7 |

| Weight (kg) | 76.5±9.1 | 72.0±16.4 |

| Height (cm) | 168.7±5.3 | 166.7±8.6 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.0 ±3.0 | 25.8±4.9 |

| Echocardiogram | ||

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 59.7±18.7 | 29.1±4.9* |

| Medication | ||

| Thiazide diuretics (N) | – | 7 |

| Spironolactone (N) | – | 4 |

| Digitalis (N) | – | 5 |

| Carvedilol (N) | – | 10 |

| ACE Inhibitors/ AR blockers (N) | – | 10 |

| Incremental exercise | ||

| Peak work rate (W) | 141±28 | 80±26* |

| Peak V̇O2 (mL/min) | 1758±313 | 1134±416* |

| Peak V̇O2 (mL·min-1·kg-1) | 23.1±3.8 | 15.4±4.9* |

| V̇O2LT (mL/min) | 746±120 | 634±153 |

| V̇O2-work rate slope (mL·min-1·W-1) | 10.5±0.8 | 8.8±1.7* |

| Peak RER | 1.21±0.09 | 1.04±0.16* |

| Peak V̇E/V̇CO2 | 34.3±5.4 | 47.6±13.5* |

| Peak PETCO2 (mmHg) | 35.0±5.2 | 27.1±10.5 |

| Peak HR (bpm) | 140±26 | 131±15 |

Data are reported as means ± SD or frequency (N). ACE: angiotensin-converting enzyme; AR: angiotensin receptor; V̇O2: oxygen uptake; LT: lactate threshold; RER: gas exchange ratio; V̇E: ventilation; V̇CO2: carbon dioxide output; PET: end-tidal partial pressure; HR heart rate.

P<0.05 (unpaired t-test).

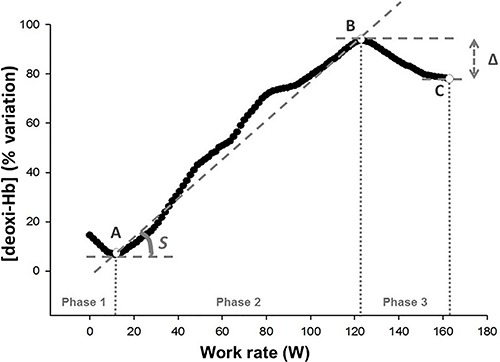

As previously described in normal subjects (4,10), deoxi-Hb response curve as a function of increasing work rate was S-shaped i.e., it resembled a sigmoid in all subjects. From the raw signal, we initially identified two inflection points: point “A” corresponded to the work rate after exercise onset at which deoxi-Hb started to systematically increase, and from point “A” onward we applied linear regression to deoxi-Hb. Point “B” corresponded to the work rate at which there was a systematic departure from linearity.

The range of work rates before point “A”, between points “A” and “B” and after point “B” up to peak exercise (point “C”) were named phases “1”, “2” and “3”, respectively. In addition to the increase in slope (S) of deoxi-Hb throughout phase 2, we calculated the deoxi-Hb difference (“Δ”) between points “B” and “C” (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Representative deoxygenated hemoglobin concentration (deoxi-Hb) response profile (% rest-peak variation) as a function of increasing exercise intensity in a healthy control. Points “A” and “B” correspond to the first and second inflection points. Point “C” is the peak work rate. In addition to the slope (S) of deoxi-Hb increase throughout phase “2”, deoxi-Hb difference between points “B” and “C” is depicted (“Δ”).

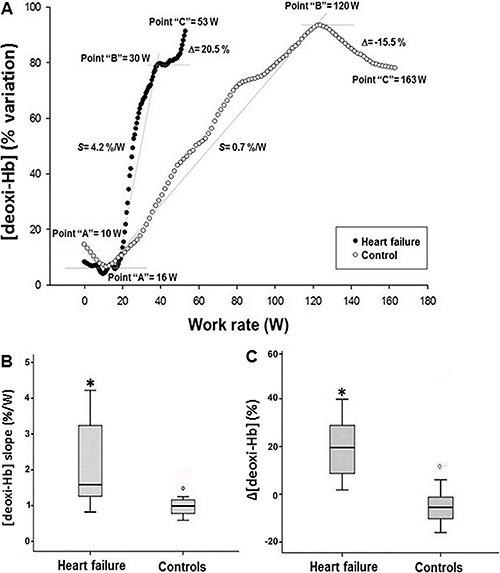

As shown in Figure 2 for representative subjects and in Table 2 and Figure 2 for mean data, patients presented with significant steeper deoxi-Hb slope than controls (P<0.01). Moreover, while deoxi-Hb remained stable or even decreased during phase “3” in all but one control (i.e., null or negative “Δ”), there were systematic increases in deoxi-Hb in all patients (P<0.05). Steeper deoxi-Hb-work rate slope was associated with lower peak work rate in patients (r=–0.73; P=0.01).

Figure 2. Representative deoxygenated hemoglobin concentration (deoxi-Hb) response profile (% rest-peak variation) as a function of increasing exercise intensity in a representative control and a patient with heart failure (panel A). Lower panels show box plots comparing the slope of deoxi-Hb increase as a function of work rate throughout phase “2” (panel B) and Δdeoxi-Hb difference between points “B” and “C” (panel C). Data are reported as means±SD. Variables: [deoxi-Hb] Slope (S): Slope of the ratio [deoxi-Hb]/work-rate (%variation/W); Δ[deoxi-Hb] (Δ): variation of [deoxi-Hb] at the maximum work-rate point (C) to the second inflection point (B). *P<0.05: Unpaired t-test (panel B) and Mann-Whitney test (panel C).

Table 2. Key variables of deoxygenated hemoglobin concentration (deoxi-Hb)-work rate relationship in healthy controls and patients with heart failure.

| Variables | Controls (n=10) | Heart failure (n=10) |

|---|---|---|

| Point “A” (W) | 19±14 | 18±11 |

| Point “B” (W) | 111±32 | 53±19* |

| [deoxy-Hb] slope (%/W) | 1.0±0.3 | 2.2±1.3* |

| Δ[deoxy-Hb] (%) | -0.5±18.9 | 20.3±12.9* |

Point “A”: work rate after exercise onset at which deoxi-Hb started to increase; Point “B”: work rate at which there was a systematic departure from linearity; [deoxi-Hb] Slope: slope of the ratio [deoxi-Hb]/work-rate (%variation/W); Δ[deoxi-Hb]: variation of [deoxi-Hb] at the maximum work-rate point (C) to the second inflection point (B). Data are reported as mean±SD.

P<0.05: unpaired t-test, except “Δ” (Mann-Whitney test).

Discussion

This prospective study established a simplified approach to unravel abnormalities in peripheral muscle O2 delivery (i.e., lower blood flow in non-hypoxemic patients) as indicated by changes in NIRS-based deoxi-Hb during ramp-incremental cardiopulmonary exercise test in heart failure patients. Our results indicate that, compared to controls, patients presented with steeper mid-exercise slope of deoxi-Hb as a function of work rate coupled with lack of late-exercise stability (or even decreasing deoxi-Hb). We interpret these results as evidence of faster and higher O2 extraction to compensate for impaired convective and diffusive O2 flow to muscle mitochondria (10). This approach might prove useful to assess the effects of pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods aimed at improving intra-muscular microvascular hemodynamics in this patient population. The proposed approach can be easily applied in clinical settings, as it does not require data fitting with complex mathematical functions (7). Moreover, deoxi-Hb is reported as a function of work rate, and V̇O2 measurements (i.e., cardiopulmonary exercise test) are not mandatory. Importantly, the proposed parameters (slope and “Δ”) are largely effort-independent, being recorded during submaximal exercise.

From a mechanistic standpoint, it has been long established that the key factors modulating O2 delivery-utilization matching in contracting appendicular muscles include: a) the muscle “pump” effect; b) local vasodilatation; c) parasympathetic and sympathetic tones, and d) differential patterns of muscle fiber recruitment, as reviewed by other authors (4,10,19). Based on these premises, we interpreted the S-shaped pattern of muscle deoxygenation (deoxi-Hb) depicted in Figure 1 as indicating: a) an early phase (“1”) in which proportional increases in O2 delivery and O2 requirements (V̇O2) led to a stable O2 extraction (∼deoxi-Hb), b) a subsequent phase (“2”) in which deficits in O2 delivery relative to fast-increasing V̇O2 produced a marked increase in O2 extraction, and c) a final phase (“3”) in which O2 delivery and O2 requirements were once again matched leading to a stable rate of O2 extraction (or even decreasing if O2 delivery becomes excessive relative to instantaneous O2 needs) (4,10). This model is consistent with previous contentions by Spencer et al (11), who found that the deoxi-Hb response profile during ramp-incremental exercise in healthy young males consisted of three distinct phases, in which the latter two were approximately linear, i.e., phases “1” and “2” herein described.

In this context, steeper phase “2” deoxi-Hb-work rate slope in patients than controls is strongly suggestive of impaired O2 delivery-utilization matching in the former group. It is noteworthy that these abnormalities occurred despite a shallower V̇O2-work rate slope in patients. Thus, even if changes in O2 requirements were lower in patients, marked deficits in Q̇m likely precluded a corresponding increase in O2 delivery. In other words, V̇O2/extraction ratio was markedly reduced in patients, a finding consistent with impaired O2 delivery. Increased O2 extraction in patients might have also been influenced by lactacidosis-induced rightward shifts in the oxy-hemoglobin dissociation curve (Bohr effect) and/or greater recruitment of O2-costly type II fibers. Thus, a direct quantitative (inverse) relationship between Q̇m and deoxi-Hb should not be attempted.

Progressive increase in late-exercise (phase “3”) deoxi-Hb in patients, but not in controls, is another evidence of poorer muscle O2 delivery-utilization matching in heart failure conditions. In fact, there is growing evidence that despite progressive increases in work rate (and V̇O2), cardiac output might stabilize (or even decrease) near peak exercise in these patients (20–22). Microvascular perfusion-muscle fiber recruitment uncoupling (4,10,21) and sympathetic over-excitation (23) may also further impair Q̇m near exercise termination. Moreover, type II fibers (with lower ATP/O2 ratio) are mostly recruited at higher compared to lower work rates (24,25), which might have contributed to muscle O2 delivery- V̇O2 mismatch in phase “3”.

As a noninvasive, cross-sectional study our investigation has some limitations that should be highlighted. We assume, as others (5,8,26–28), that deoxi-Hb reflects muscle fractional O2 extraction (C(a-v)O2); however, we did not measure blood gas tensions. We also assumed that deoxi-Hb at a specific site gives a rough estimate of overall muscle O2 extraction (8,14,16,28). Koga et al. (18), however, found large heterogeneity in Q̇m-V̇O2 distribution in normal subjects, a phenomenon that might be more relevant for poorly perfused muscles. There is mounting evidence that Q̇m-V̇O2 distribution abnormalities worsen as disease progresses in humans (29,30) and animals (31,32). Thus, our approach needs to be tested in more impaired patients. Finally, patients performed a cycle ergometer test as the NIRS signal quickly deteriorates during fast walking; thus, our approach is unlikely to be feasible for treadmill-based tests.

In conclusion, we presented a practical approach to interpret the deoxi-Hb signal by NIRS during ramp-incremental cycle ergometry in heart failure patients. Impairments in O2 delivery, likely reflective of poor muscle blood flow in non-hypoxemic patients, were non-invasively uncovered by steeper mid-exercise slope of deoxi-Hb as a function of work rate and increasing (instead of stable or decreasing) deoxi-Hb near peak exercise. This novel strategy might prove useful to assess the effects of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions aimed at improving skeletal muscle perfusion in this patient population.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all colleagues from the Pulmonary Function and Clinical Exercise Physiology Unit, Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), Brazil for friendly collaboration. This study was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Brazil.

References

- 1.Hirai DM, Musch TI, Poole DC. Exercise training in chronic heart failure: improving skeletal muscle O2 transport and utilization. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;309:H1419–H1439. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00469.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, et al. ACC/AHA Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:e1–e90. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wielenga RP, Coats AJS, Mosterd WL, Huisveld IA. The role of exercise training in chronic heart failure. Heart. 1997;78:431–436. doi: 10.1136/hrt.78.5.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boone J, Koppo K, Barstow TJ, Bouckaert J. Pattern of deoxy[Hb + Mb] during ramp cycle exercise: influence of aerobic fitness status. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;105:851–859. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0969-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poole DC, Barstow TJ, McDonough P, Jones AM. Control of oxygen uptake during exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:462–474. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31815ef29b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karavidas A, Arapi SM, Pyrgakis V, Adamopoulos S. Functional electrical stimulation of lower limbs in patients with chronic heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2010;15:567–579. doi: 10.1007/s10741-010-9171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sperandio PA, Oliveira MF, Rodrigues MK, Berton DC, Treptow E, Nery LE, et al. Sildenafil improves microvascular O2 delivery-to-utilization matching and accelerates exercise O2 uptake kinetics in chronic heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H1474–H1480. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00435.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferreira LF, Townsend DK, Lutjemeier BJ, Barstow TJ. Muscle capillary blood flow kinetics estimated from pulmonary O2 uptake and near-infrared spectroscopy. J Appl Physiol. 2005;98:1820–1828. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00907.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrari M, Mottola L, Quaresima V. Principles, techniques, and limitations of near infrared spectroscopy. Can J Appl Physiol. 2004;29:463–487. doi: 10.1139/h04-031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferreira LF, Koga S, Barstow TJ. Dynamics of noninvasively estimated microvascular O2 extraction during ramp exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1999–2004. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01414.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spencer MD, Murias JM, Paterson DH. Characterizing the profile of muscle deoxygenation during ramp incremental exercise in young men. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112:3349–3360. doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2323-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boone J, Bouckaert J, Barstow TJ, Bourgois J. Influence of priming exercise on muscle deoxy[Hb + Mb] during ramp cycle exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;112:1143–1152. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2068-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neder JA, Nery LE, Castelo A, Andreoni S, Lerario MC, Sachs A, et al. Prediction of metabolic and cardiopulmonary responses to maximum cycle ergometry: a randomised study. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:1304–1313. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.14613049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grassi B, Pogliaghi S, Rampichini S, Quaresima V, Ferrari M, Marconi C, et al. Muscle oxygenation and pulmonary gas exchange kinetics during cycling exercise on-transitions in humans. J Appl Physiol. 2003;95:149–158. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00695.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boushel R, Langberg H, Olesen J, Gonzales-Alonzo J, Bulow J, Kjaer M. Monitoring tissue oxygen availability with near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) in health and disease. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2001;11:213–222. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2001.110404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferreira LF, Poole DC, Barstow TJ. Muscle blood flow-O2 uptake interaction and their relation to on-exercise dynamics of O2 exchange. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2005;147:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Azevedo D, Medeiros WM, de Freitas FF, Ferreira Amorim C, Gimenes AC, Neder JA, et al. High oxygen extraction and slow recovery of muscle deoxygenation kinetics after neuromuscular electrical stimulation in COPD patients. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2016;116:1899–1910. doi: 10.1007/s00421-016-3442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koga S, Poole DC, Ferreira LF, Whipp BJ, Kondo N, Saitoh T, et al. Spatial heterogeneity of quadriceps muscle deoxygenation kinetics during cycle exercise. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:2049–2056. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00627.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirai DM, Copp SW, Holdsworth CT, Ferguson SK, McCullough DJ, Behnke BJ, et al. Skeletal muscle microvascular oxygenation dynamics in heart failure: exercise training and nitric oxide-mediated function. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;306:H690–H698. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00901.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanabe Y, Nakagawa I, Ito E, Suzuki K. Hemodynamic basis of the reduced oxygen uptake relative to work rate during incremental exercise in patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2002;83:57–62. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5273(02)00013-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonough P, Behnke BJ, Padilla DJ, Musch TI, Poole DC. Control of microvascular oxygen pressures in rat muscles comprised of different fibre types. J Physiol. 2005;563:903–913. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.079533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rolim NP, Mattos KC, Brum PC, Baldo MV, Middlekauff HR, Negrão CE. The decreased oxygen uptake during progressive exercise in ischemia-induced heart failure is due to reduced cardiac output rate. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39:297–304. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2006000200018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferreira LF, McDonough, Behnke BJ, Musc TI, Poole DC. Blood flow and O2 extraction as a function of O2 uptake in muscles composed of different fiber types. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2006;153:237–249. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krustrup P, Söderlund K, Mohr M, Bangsbo J. The slow component of oxygen uptake during intense, sub-maximal exercise in man is associated with additional fibre recruitment. Eur J Physiol. 2004;447:855–866. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1203-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boone J, Koppo K, Barstow TJ, Bouckaert J. Aerobic fitness, muscle efficiency, and motor unit recruitment during ramp exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:402–408. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181b0f2e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bauer TA, Reusch JE, Levi M, Regensteiner JG. Skeletal muscle deoxygenation after the onset of moderate exercise suggests slowed microvascular blood flow kinetics in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2880–2885. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiappa GR, Borghi-Silva A, Ferreira LF, Carrascosa C, Oliveira CC, Maia J, et al. Kinetics of muscle deoxygenation are accelerated at the onset of heavy-intensity exercise in patients with COPD: relationship to central cardiovascular dynamics. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104:1341–1350. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01364.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sperandio PA, Borghi-Silva A, Barroco AC, Nery LE, Almeida DR, Neder A. Microvascular oxygen delivery-to-utilization mismatch at the onset of heavy-intensity exercise in optimally treated patients with CHF. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297:1720–1728. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00596.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lanfranconi F, Borrelli E, Ferri A, Porcelli S, Maccherini M, Chiavarelli M, et al. Noninvasive evaluation of skeletal muscle oxidative metabolism after heart transplant. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:1374–1383. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000228943.62776.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jendzjowsky NG, Tomczak CR, Lawrance R, Taylor DA, Tymchak WJ, Riess KJ, et al. Impaired pulmonary oxygen uptake kinetics and reduced peak aerobic power during small muscle mass exercise in heart transplant recipients. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1722–1727. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00725.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diederich ER, Behnke BJ, McDonough P, Kindig CA, Barstow TJ, Poole DC, et al. Dynamics of microvascular oxygen partial pressure in contracting skeletal muscle of rats with chronic heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;56:479–486. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(02)00545-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Behnke BJ, Delp MD, Poole DC, Musch TI. Aging potentiates the effect of congestive heart failure on muscle microvascular oxygenation. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1757–1763. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00487.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]