Abstract

Background:

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding is a common medical emergency associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The clinical presentation depends on the amount and location of hemorrhage and the endoscopic profile varies according to different etiology. At present, there are limited epidemiological data on upper GI bleed and associated mortality from India, especially in the middle and elderly age group, which has a higher incidence and mortality from this disease.

Aim:

This study aims to study the clinical and endoscopic profile of middle aged and elderly patients suffering from upper GI bleed to know the etiology of the disease and outcome of the intervention.

Materials and Methods:

Out of a total of 1790 patients who presented to the hospital from May 2015 to August 2017 with upper GI bleed, and underwent upper GI endoscopy, data of 1270 patients, aged 40 years and above, was compiled and analyzed retrospectively.

Results:

All the patients included in the study were above 40 years of age. Majority of the patients were males, with a male to female ratio of 1.6:1. The most common causes of upper GI bleed in these patients were portal hypertension-related (esophageal, gastric and duodenal varices, portal hypertensive gastropathy, and gastric antral vascular ectasia GAVE), seen in 53.62% of patients, followed by peptic ulcer disease (gastric and duodenal ulcers) seen in 17.56% of patients. Gastric erosions/gastritis accounted for 15.20%, and duodenal erosions were seen in 5.8% of upper GI bleeds. The in-hospital mortality rate in our study population was 5.83%.

Conclusion:

The present study reported portal hypertension as the most common cause of upper GI bleeding, while the most common endoscopic lesions reported were esophageal varices, followed by gastric erosion/gastritis, and duodenal ulcer.

KEYWORDS: Esophageal varices, portal hypertension, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy

INTRODUCTION

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, defined as bleeding derived from a source proximal to the ligament of Treitz, is a common and potentially life-threatening GI emergency with a wide range of clinical severity, ranging from insignificant bleeds to catastrophic exsanguinating hemorrhage,[1] and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.[2]

The incidence of upper GI bleed ranges from 50 to 150/100,000 population annually, and time trend analyses suggest that aged people constitute an increasing proportion of those presenting with acute upper GI bleed.[3] As many as 70% of acute upper GI bleed episodes occur in patients older than 60 years,[4] and the incidence increases with age[5] probably because of the increased consumption of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which provoke ulcerogenesis, in elderly patients. About two-thirds of all patients presenting to the emergency department with GI bleed have upper GI bleed as the cause.[6] Patients can be divided as having either variceal or nonvariceal sources of upper GI hemorrhage as the two have different management protocols and prognosis.[7] The first includes lesions that arise by virtue of portal hypertension, namely, gastroesophageal varices and portal hypertensive gastropathy; and the second includes lesions seen in the general population (peptic ulcer, erosive gastritis, reflux esophagitis, Mallory–Weiss syndrome, tumors, etc.).

Advanced age has been consistently identified as a risk factor for mortality among patients presenting with upper GI bleed,[3,5] presumably because of the high prevalence of comorbid illnesses (such as cardiovascular[8] disease) in elderly as compared with younger patients with upper GI bleed. Mortality rates ranging from 12% to 35% for those aged over 60 years, compared with <10% for patients younger than 60 years of age, have been reported in previous studies[5,9] with overall mortality rates of 5%–11%, representing a serious entity.[10] The incidence of upper GI bleeding is 2-fold greater in males than in females, in all age groups; however, the death rate is similar in both sexes.[11] The predisposing factors that lead to the occurrence of these hemorrhagic instances are largely linked to the lifestyle of the affected persons.

The primary diagnostic test for evaluation of upper GI bleeding is endoscopy. Endoscopy for upper GI bleed has a sensitivity of 92%–98% and specificity of 30%–100%.[12] Early endoscopy and endoscopic appearance of certain lesions help in diagnosis and to guide care and thereby reduce rebleeding, requirement for transfusion, the need for surgery, costs and duration of hospitalization.[13,14]

At present, there are limited data on clinical and endoscopic profile of patients of upper GI bleeding from India and particularly from this region. Therefore, this study was planned to identify clinical and endoscopic profile of patients with upper GI bleed presenting to our hospital and to study the mortality rates and patterns in this group of patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 1790 patients with upper GI bleeding presented to Govt. Medical College, Jammu, between May 2015 and August 2017 and underwent upper GI endoscopy, out of which clinical and endoscopic data of 1270 patients, aged 40 years or more, was compiled and analyzed in this study retrospectively. The data analyzed included a history of GI bleeding (hematemesis, melena), risk factors for liver disease including alcoholism, and history for intake of antiplatelet agents or NSAIDs. Patients with a history suggestive of chronic liver disease were given injection terlipressin 2 mg intravenous (IV) stat, followed by 1 mg IV 4–6 hourly. All patients were given injection pantoprazole 80 mg IV stat, followed by 40 mg IV 6 hourly. Patients were subjected to upper GI endoscopy, preferably within the first 24 h, after taking an informed consent. It was done by a single gastroenterologist using Olympus EVIS EXERA III CV190 Processor gastroscope (GIF H190)/Fuginon (2200 Processor) gastroscope (EG) 265WR and was done under conscious sedation using 15% lidocaine local anesthetic spray.

Collected data were analyzed and results were displayed in tables and figures, with the categorical variables presented as numbers and percentages.

RESULTS

The study population comprised of 1270 patients with upper GI bleed who came to the hospital from May 2015 to August 2017. All the patients included in the study were above 40 years of age, and the eldest patient was 72-year-old. The population comprised of 781 males (61.50% patients) and 489 females (38.50% patients), showing a male to female ratio of 1.6:1.

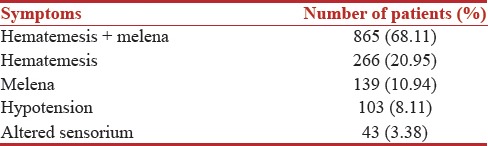

After studying the clinical profile of the patients included in the study, it was seen that the majority of the patients had both hematemesis and melena (68.11% patients), 20.95% of the patients presented with hematemesis only, and 10.94% patients presented with melena only. The clinical profile of patients is mentioned in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical profile of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding

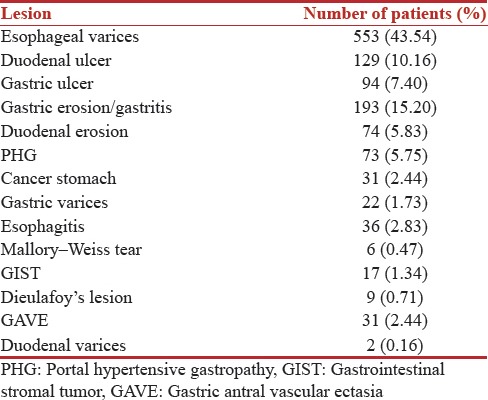

In this study, after upper GI endoscopy data were compiled and studied, it was found that the most common type of lesion in these patients with upper GI bleed was esophageal varices (43.54% patients), and the 2nd most common type was gastric erosion/gastritis (15.20% patients). Portal hypertension-related causes of GI bleed (esophageal, gastric and duodenal varices, portal hypertensive gastropathy, and gastric antral vascular ectasia [GAVE]) were seen in 53.62% of patients, and peptic ulcers (gastric and duodenal ulcers) were seen in 17.56% of patients. The complete list of lesions is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Endoscopic lesions in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding

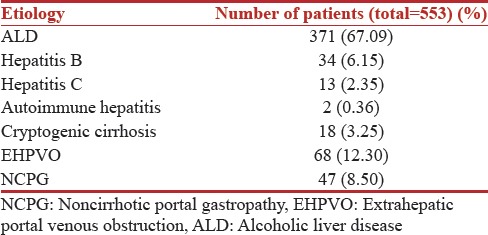

When the clinical and laboratory investigational data was studied, it was found that out of all the patients with esophageal varices as the cause of portal hypertension-related upper GI bleeding, 67.09% had alcoholic liver disease (ALD), while 12.30% patients had extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. The concerned etiological data has been shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Etiological data of patients with portal hypertension-related upper gastrointestinal bleeding presenting with esophageal varices

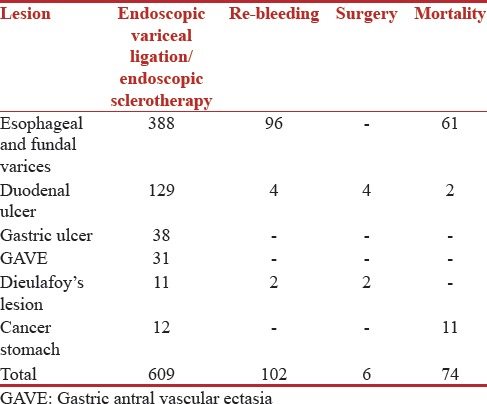

It was also found in the study that after endoscopic intervention was provided to the patients based on their endoscopic profile, 96 patients, out of a total of 575 patients who had varices, had an episode of rebleeding, and in-hospital mortality was 61 out of these 575 patients. Similarly, 4 out of the 129 patients who had duodenal ulcer had an episode of rebleeding, and the in-hospital mortality was 2 out of these 129 patients. The detailed list is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Outcome of intervention

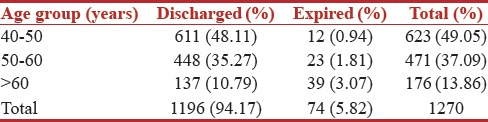

There was a correlation between age and in-hospital mortality of patients. Most of the patients who were discharged from the hospital belonged to the lowest age group, and the highest age group had a maximum mortality rate. The relevant data are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Relationship between age of patients and outcome

DISCUSSION

Upper GI bleeding is a common medical emergency in a tertiary care hospital. Despite advances in diagnostic modalities and therapy, the mortality of GI bleeding has not decreased much during the past 50 years. Most of the patients with GI bleed are elderly and with comorbid conditions, which contribute to the high mortality from GI bleeding.

Our study was aimed at understanding the clinical and endoscopic profile of elderly patients who presented to the hospital with upper GI bleed, to know their etiologic and mortality patterns.

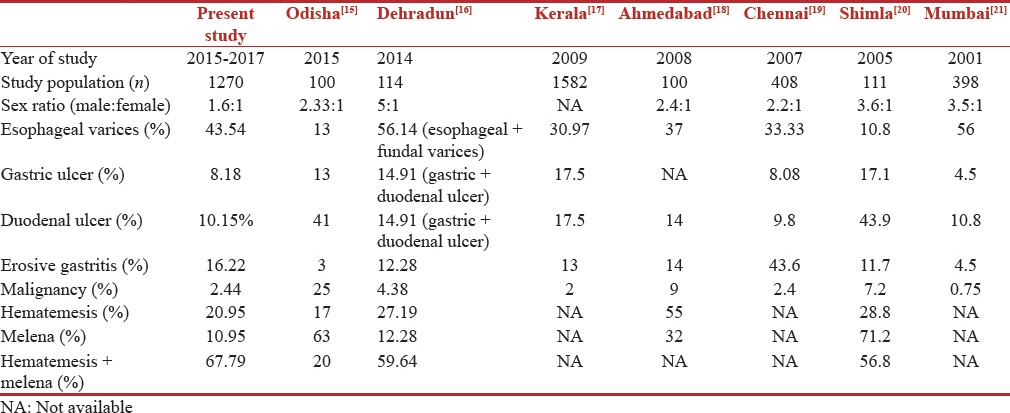

Table 6 shows the comparison of the patient profile of upper GI bleed from different parts of India.

Table 6.

Comparison of etiological and clinical spectrum of upper gastrointestinal bleed in different regions of India

Studies done in the past have shown an increase in mortality with advancing age of the patients with worse outcome noticed in the geriatric population.

Between May 2015 and August 2017, 1790 patients presented to our hospital with upper GI bleed, out of which, 1270 patients were above 40 years of age, showing that 70.95% patients with upper GI bleed were elderly (40 years and above). In a study done by Lakhwani et al.,[22] upper GI bleeding was more common in the older age group of 60 years.

Among 1270 patients in our study, upper GI bleeding was found to be more common in men (61.50%) as compared to women (38.50%). In a study done by Singh and Panigrahi from coastal Odisha, India it was found that upper GI bleeding is more common in males than females with a male-to-female ratio of 6:1.[23] A study by Rodrigues and Shenoy et al.[24] showed that out of all the patients with upper GI bleeding, 74.2% were males and 25.8% were females. Kashyap et al. found that out of 111 patients with upper GI bleeding included in their study, 78.4% patients were males.[20]

In our study, out of a total of 1270 patients, the majority (865, i.e., 68.11%) presented with both hematemesis and melena, while 266 (20.95%) presented with hematemesis only, and 139 (10.94%) had melena only. In studies done by Singh and Panigrahi,[23] and Bambha et al.,[25] melena was the presenting complaint in 95.06% and 19% patients, respectively, and hematemesis was present in 43.09% and 28% patients, respectively, while both hematemesis and melena were seen in 41.78% and 52% patients, respectively.

When variceal versus nonvariceal bleeding is considered as the etiology of upper GI bleed, there are variable results in India. In the present study, 53.62% of patients had portal hypertension-related varices, gastropathy, and GAVE, and 46.38% of patients had bleeding due to other causes which included 17.56% patients with peptic ulcer disease (gastric or duodenal ulcer), 15.20% patients with gastric erosions/gastritis, 5.83% patients with duodenal erosion, 2.83% patients with esophagitis, 2.44% patients with gastric malignancy, 1.34% patients with GIST, 0.71% patients with Dieulafoy's lesion, and 0.47% patients with Mallory–Weis tear. In contrast, in a recent study conducted in eastern India in 2015, duodenal ulcer was found to be the most common cause of upper GI bleed (41% patients), and variceal bleed was found in only 13% patients.[15] The higher number of patients with variceal bleeding in our study was seen because ALD is highly prevalent in North Indian region, and since ours is the only referral hospital in the Jammu region of J and K and is the only hospital in this region where gastroscopy is done, all the critical patients are referred to our hospital, which may have added on to the percentage of patients with variceal bleed.

Overall in-hospital mortality in our study was 74 out of 1270 patients (5.83%), out of which 61 patients (4.80%) had variceal bleed, 11 patients (0.87%) had stomach cancer, and 2 patients (0.15%) had peptic ulcer as the cause of upper GI bleeding. A study by Chalasani et al.[26] found the in-hospital mortality rate to be 14.2% out of a total of 231 patients included in the study. Carbonell et al.[27] reviewed the clinical records of all patients with cirrhosis due to variceal bleeding during the years 1980, 1985, 1990, 1995, and 2000, and the in-hospital mortality rate steadily decreased over the study period (42.6%, 29.9%, 25%, 16.2%, and 14.5% in 1980, 1985, 1990, 1995, and 2000, respectively).

Rapid clinical assessment and resuscitation is the first thing to be done while attending unstable patients with severe bleeding, followed by the diagnostic evaluation. Early upper GI endoscopy (within 24 h of presentation) is recommended in most patients because it confirms the diagnosis and allows for targeted endoscopic treatment, resulting in reduced morbidity and mortality.[13,14] Rebleeding can occur in 10%–20% of patients despite successful endoscopic therapy and endoscopic therapy must be attempted once more in such patients. Surgical intervention may be required in patients with severe and persistent bleeding.

CONCLUSION

Endoscopy is an important diagnostic as well as therapeutic modality for patients with upper GI bleeding. The present study reported portal hypertension as the most common cause of upper GI bleeding, followed by peptic ulcer disease. The most common endoscopic lesions reported were esophageal varices, followed by gastric erosion/gastritis, and duodenal ulcer.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Selection of patients for early discharge or outpatient care after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. National audit of acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet. 1996;347:1138–40. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90607-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghosh S, Watts D, Kinnear M. Management of gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Postgrad Med J. 2002;78:4–14. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.915.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomopoulos KC, Vagenas KA, Vagianos CE, Margaritis VG, Blikas AP, Katsakoulis EC, et al. Changes in aetiology and clinical outcome of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding during the last 15 years. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:177–82. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200402000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EA, Geraedts AA, Tijssen JG, Reitsma JB, et al. Acute upper GI bleeding: Did anything change? Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1494–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:222–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srygley FD, Gerardo CJ, Tran T, Fisher DA. Does this patient have a severe upper gastrointestinal bleed? JAMA. 2012;307:1072–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ginn JL, Ducharme J. Recurrent bleeding in acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: Transfusion confusion. CJEM. 2001;3:193–8. doi: 10.1017/s1481803500005534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yamaguchi Y, Yamato T, Katsumi N, Morozumi K, Abe T, Ishida H, et al. Endoscopic hemostasis: Safe treatment for peptic ulcer patients aged 80 years or older? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:521–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.02960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen S, Riis A, Nørgaard M, Sørensen HT, Thomsen RW. Short-term mortality after perforated or bleeding peptic ulcer among elderly patients: A population-based cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.British Society of Gastroenterology Endoscopy Committee. Non-variceal upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage: Guidelines. Gut. 2002;51(Suppl 4):iv1–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.suppl_4.iv1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meaden C, Makin AJ. Diagnosis and treatment of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding. Curr Anaesth Crit Care. 2004;15:123–32. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaskolka JD, Binkhamis S, Prabhudesai V, Chawla TP. Acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage: Radiologic diagnosis and management. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2013;64:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.carj.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316–21. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, Sung J, Hunt RH, Martel M, et al. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:101–13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panigrahi PK, Mohanty SS. A study on endoscopic evaluation of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Evid Based Med Healthc. 2016;3:1245–52. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anand D, Gupta R, Dhar M, Ahuja V. Clinical and endoscopic profile of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding at tertiary care center of North India. J Dig Endosc. 2014;5:139–43. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gajendra O, Ponsek T, Varghese J, Sadasivan S, Nair P, Narayanan VA. Single center study of upper GI endoscopic findings in patients with overt and occult upper GI bleed. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2009;28:A111. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lakhani K, Mundhara S, Sinha R, Gamit Y, Sharma R. Clinical Profile of Acute Upper Gastro Intestinal Bleeding. [Last accessed on 2012 Feb 15]. Available from: http://www.japi.org/july_2008/gastro_enterology_hepatology .

- 19.Krishnakumar R, Padmanabhan P, Premkumar, Selvi C, Ramkumar, Joe A. Upper GI bleed - A study of 408 cases. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2007;26(Suppl 2):A133. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kashyap R, Mahajan S, Sharma B, Jaret P, Patial RK, Rana S, et al. A clinical profile of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding at moderate altitude. JIACM. 2005;6:224–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rathi P, Abraham P, Rajeev Jakareddy, Pai N. Spectrum of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Western India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2001;20(Suppl 2):A37. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lakhwani MN, Ismail AR, Barras CD, Tan WJ. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in Kuala Lumpur hospital, Malaysia. Med J Malaysia. 2000;55:498–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singh SP, Panigrahi MK. Spectrum of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in coastal Odisha. Trop Gastroenterol. 2013;34:14–7. doi: 10.7869/tg.2012.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodrigues G, Shenoy R, Rao A. Profile of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal: Bleeding in a tertiary referral hospital. Internet J Surg. 2004;5:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bambha K, Kim WR, Pedersen R, Bida JP, Kremers WK, Kamath PS, et al. Predictors of early re-bleeding and mortality after acute variceal haemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. Gut. 2008;57:814–20. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.137489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chalasani N, Kahi C, Francois F, Pinto A, Marathe A, Bini EJ, et al. Improved patient survival after acute variceal bleeding: A multicenter, cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:653–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carbonell N, Pauwels A, Serfaty L, Fourdan O, Lévy VG, Poupon R, et al. Improved survival after variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis over the past two decades. Hepatology. 2004;40:652–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.20339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]