Abstract

Background

Reported tuberculosis (TB) incidence globally continues to be heavily influenced by expert opinion of case detection rates and ecological estimates of disease duration. Both approaches are recognised as having substantial variability and inaccuracy, leading to uncertainty in true TB incidence and other such derived statistics.

Methods

We developed Bayesian binomial mixture geospatial models to estimate TB incidence and case detection rate (CDR) in Ethiopia. In these models the underlying true incidence was formulated as a partially observed Markovian process following a mixed Poisson distribution and the detected (observed) TB cases as a binomial distribution, conditional on CDR and true incidence. The models use notification data from multiple areas over several years and account for the existence of undetected TB cases and variability in true underlying incidence and CDR. Deviance information criteria (DIC) were used to select the best performing model.

Results

A geospatial model was the best fitting approach. This model estimated that TB incidence in Sheka Zone increased from 198 (95% Credible Interval (CrI) 187, 233) per 100,000 population in 2010 to 232 (95% CrI 212, 253) per 100,000 population in 2014. The model revealed a wide discrepancy between the estimated incidence rate and notification rate, with the estimated incidence ranging from 1.4 (in 2014) to 1.7 (in 2010) times the notification rate (CDR of 71% and 60% respectively). Population density and TB incidence in neighbouring locations (spatial lag) predicted the underlying TB incidence, while health facility availability predicted higher CDR.

Conclusion

Our model estimated trends in underlying TB incidence while accounting for undetected cases and revealed significant discrepancies between incidence and notification rates in rural Ethiopia. This approach provides an alternative approach to estimating incidence, entirely independent of the methods involved in current estimates and is feasible to perform from routinely collected surveillance data.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12879-017-2759-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Incidence, Spatial analysis, Binomial mixture models

Background

Population level tuberculosis (TB) prevalence and incidence studies are resource and time-intensive, and so impractical for regular evaluation of TB trends in most settings. Almost universally, data acquired from routine programmatic TB notifications are adjusted by a number of methods, including expert opinion regarding case detection rates (CDR) in the local context, to estimate and report TB incidence [1]. In the few countries with recent and well-conducted prevalence surveys, incidence is calculated from a combination of these survey findings and estimates of the duration of disease, with the latter derived from the pre-chemotherapy era or from mathematical models [2, 3]. Because of uncertainties in the duration of disease, incidence estimates from these methods differ and optimal methods remain elusive [2]. As a result, significant uncertainty exists regarding the true TB incidence and other programmatically important unobserved values, such as CDR [4].

Given these uncertainties, notification data with imputation of estimated missing cases have been relied on in many epidemiological TB studies, including in spatiotemporal characterization studies [5–8]. Failure to appropriately account for missed cases could reduce the power of such studies to detect factors affecting population-level TB dynamics, and introduce systematic bias of estimates of the effect of covariates towards the null [9]. Both factors could obscure important population-level patterns. Similarly, interpretation of maps from these studies is problematic, as spatial patterns in notification data could reflect spatial dynamics in the true underlying incidence or case detection performance. Thus these maps could be biased to areas with better case detection performance, leading to resource misallocation. One such cause of bias is systematic under-reporting which could also vary depending on the availability of health care facilities.

To address this bias, we aimed to estimate TB incidence and case detection in Ethiopia using an alternative Bayesian methods based on routinely collected surveillance data, without the need for expert opinion regarding programmatic performance or estimates of duration of disease.

Methods

We collected data on TB patients diagnosed between 2010 and 2014 in all 66 kebeles (the smallest geographical administrative unit in Ethiopia) of Sheka Zone (a remote zone in the country). These TB cases were pooled based on kebele of residence and year. We produced population density using census data and kebele shape files obtained from the Central Statistical Agency (CSA). Data on health facility availability were obtained from the Zonal health department. At the time of data collection, close to 50% of health facilities in the Zone did not have sputum microscopy, and there was no access to chest x-ray and culture facilities. Further details of the data and the study area are presented elsewhere [10].

Model development

Hidden Markov models (Bayesian geospatial binomial mixture models) were developed to estimate the true underlying but unknown TB incidence and case detection rates. Hidden Markov models(HMMs) are flexible time series models for sequences of observations that are known to be driven by an underlying state which is hidden from the observer yet is in some way predictable, such as being serially auto-correlated, geospatially correlated or through predictor variables that are observable. The value of HMMs is their ability to predict the underlying process; which they do provided the second process (the relationship between hidden and observed data) is one that itself follows rules that can be defined and in turn estimated.

Here, the underlying process is the factors that drive TB incidence in the study region. We have information including the population density, serial data and geospatial position of the kebele. The process that relates incidence to notification is the case detection rate or the proportion of cases that are notified. Given that (by definition) notification is the product of incidence and case detection rate, the natural model choice is the binomial relationship between the observation (notification) and hidden state (incidence). We also allow for kebele-specific effects on incidence, in effect leading to a (higher variance) beta-binomial distribution for observed notifications in each kebele.

Such a model when challenged by data can lead to issues of identifiability in that both high incidence/low case detection and low incidence/high case detection can explain the same notification rate. However, with sufficient information (e.g. predictors of incidence, changes over time and further information to assist in the observation model, such as presence of a health centre), the precision of model estimates can increase.

The models are informed by spatially and temporally replicated TB case counts and yield estimates of the true incidence and case detection. The parameters of this state process describe the spatiotemporal variation in incidence, which is considered as a latent variable by the model and is our key output of interest.

The state-space (the true underlying incidence) model

The number of incident TB cases (the latent state) in site i and year j, conditional on the expected mean λij is a realisation of a Poisson distribution, where the expected number λij is a product of the per capita TB rate (πij, measured as a probability between 0 and 1) and the susceptible population size in year j at site i:

| 1 |

| 2 |

The site index i runs from 1 to 66, representing the 66 kebeles and the year index j runs from 1 to 5. The logit transformed probability of incident TB (π ij ) is, in turn, a logit-linear function of the site- and year-specific covariates where population density (X i), average incidence rate in kebeles that share a border with the index kebele (Z ij ), and logit transformed incidence rate at a temporal lag of one year (π ij-1) with intercept β 0 and slopes β 1 , β 2 and β 3 (eq. 3) were fitted as fixed effects. Extra-Poisson dispersion in the incidence is accounted by specifying two types of random effects: a spatially correlated random effect (ɛ) and a non-spatially correlated random effect (ν).

| 3 |

Spatial dependence was introduced into regression in two ways: by introducing spatially structured random error and spatial lag. The spatially structured random effect, ɛ = (ɛ1, … ɛ66), accounts for the effect of spatial proximity, with the prior distribution taken as a Gaussian Conditional Autoregressive function (CAR), in which the prior probability distribution of the value of ɛi has a mean equal to the weighted average of the neighbouring random effects [11, 12] and variance following an inverse gamma distribution (shape = 0.5, scale = 0.0005). Average TB notification rate in the kebeles adjacent to an index kebele was used to define spatial lag.

The case detection model

Notified TB cases have two sources of variation: variation in the true underlying incidence (Incidence ij) and variation in the case detection process (P ij ,). As a description of the detection process giving rise to detected (observed) cases, we assumed detected cases (Y ij) by health facilities are realisations of a binomial process conditional on the underlying true incidence and case detection probability. The logit transformed case detection probability (P ij) is a linear function of the covariate of health facility (H) availability.

| 4 |

| 5 |

Hence θ1 is the log(odds ratio) of detection in the presences of a health centre compared with no health centre. To account for additional heterogeneity in CDR not captured by this covariate, we fitted a normally distributed random effect that differed by kebele and year (ɷ ij). The prior distribution of this error term had a mean of zero and a standard deviation drawn from the uniform (0, 5) distribution.

A non-informative uniform prior distribution (−10, 10) was chosen for all regression coefficients and intercept parameters (other than those already specified) to express the absence of prior information about model parameters.

We used WinBUGS 1.4.3 to fit the model using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). MCMC is a simulation tool to draw large samples from the Bayesian posterior distribution of parameters that is typically analytically intractable [13]. The model was executed in R version 3.3.1 using the R2WinBUGS library. To enhance convergence of the MCMC sampler, we standardized population density by dividing the difference between each observation and the group mean by their respective standard deviations and also truncated the normal distributions for over dispersion effects to within (−16, 16) by multiplying with an indicator uniform prior distribution [14]. We ran the model for 250,000 iterations and discarded the first 50,000. We checked whether the priors were too restrictive, by inspecting a histogram of the posterior [15], with no such evidence found.

As we were executing two interdependent logit models, the model initially did not appear to find realistic parameter space for incidence rate and case detection rates (with estimated incidence rates far exceeding observed rates). Thus the model was forced into realistic parameter space [16] by restricting the maximum incidence rate to 1%, corresponding to 1000 per 100,000 per year (this is a realistic upper limit, being five times that of current notification rates and only reported in one country in the world in 2015).

Four candidate Bayesian geospatial models were considered:

Model 1 Covariate only; logit(π ij) = β + β 1 X i + β 2 Z i j + β 3 logit(π ij − 1).

Model 2 Covariates and non-spatially correlated random effect; logit(π ij) = β + β 1 X i + β 2 Z i j + β 3 logit(π ij − 1) + ν ij .

Model 3 Covariate and spatially correlated random effect; logit(π ij)= β + β 1 X i + β 2 Z i j + β 3 logit(π ij − 1) + ɛ i .

Model 4 Full Model with covariates and all random effects included logit(π ij) = β + β 1 X i + β 2 Z i j + β 3 logit(π ij − 1) + ν ij + ɛ i .

Covariates and random effects were included/excluded to determine if this had an effect on model fit and to determine the extent to which they accounted for the spatial correlation. The effect of spatially correlated random effects was assessed by examining the credible intervals (CrI) of the coefficients of the selected covariates and incidence and case detection estimates.

The deviance information criterion (DIC) statistic was calculated for the models with or without random effect terms to determine if the addition of the geospatial component improved model fit. Maps of the summary statistics of the posterior distributions of predicted incidence and the notified cases were constructed using R.

Goodness-of-fit

We conducted posterior predictive checks to evaluate whether the models considered could likely have generated datasets that are similar to our observed dataset. This procedure uses parameter values estimated by the model using observed data to generate simulated data sets. Chi-square fit statistic was calculated to quantify the lack of fit both for the observed data and for the simulated data sets, and a Bayesian P-value was calculated to quantify the ratio between the fit statistic for the observed data and that of the simulated (perfect datasets under model assumptions) (Additional file 1). A Bayesian P-value close to 0.5 indicates a model fits the data, while a P-value close to zero or one suggests poor fit [15, 17, 18].

Results

Model selection

We found that a binomial mixture model containing the spatially structured random effect and covariates was the best fitting model, and that the model with no random effects included was the poorest fitting. When a spatially structured random effect was included into the covariate model, the DIC dropped by more than 230 whereas inclusion of the non-spatially correlated random effect reduced the DIC by only 123 (Additional file 2).

The role of the spatially correlated random effect

As well as the marked reduction in the DIC, the coefficient for the temporal lag in the state-space model became non-significant while the credible intervals surrounding other coefficients widened, but remained significant, after inclusion of the geospatial component in the state-space model. Similarly, the inclusion of non-spatially structured random effects resulted in non-significant temporal lag. By contrast, the credible intervals surrounding the predicted case detection and incidence rates became more precise when the geospatial component was added to the model (Additional file 2). In the covariate only model, the coefficient for the spatial lag covariate was not statistically significant, but became significant with the inclusion of both random effects.

Incidence and case detection rates

Outputs from the best fitting model are presented in Table 1 and show the estimated TB incidence in Sheka Zone was 198 (95% CrI: 187, 233) per 100,000 per year in 2010 and 232 (95% CrI: 212, 253) per 100,000 per year in 2014.

Table 1.

Incidence and case detection estimates in Sheka zone, Ethiopia

| Year | Median, 95% credible interval | |

|---|---|---|

| Estimated incidence | Case detection rate | |

| 2010 | 198 (187, 233) | 60 (49, 72) |

| 2011 | 218 (199, 238) | 65 (53, 77) |

| 2012 | 216 (200, 234) | 59 (47, 71) |

| 2013 | 219 (203, 236) | 67 (56, 77) |

| 2014 | 232 (212, 253) | 71 (60, 81) |

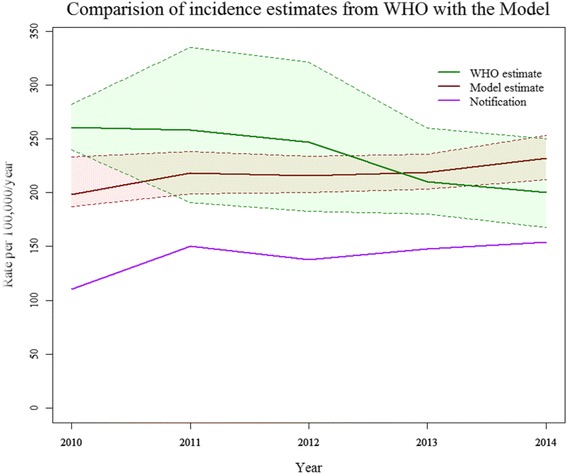

The model demonstrated a wide discrepancy between the estimated incidence rate and the notification rate, with estimated incidence 1.4 (2014) to 1.7 (2010) times the notification rate, placing CDR at 60% (95% CrI: 49, 72) in 2010 to 71% (95% CrI: 60, 81) in 2014 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of WHO estimated TB incidence for Ethiopia, with the model estimated incidence using data from Sheka Zone, Ethiopia (Broken lines represent the upper and lower 95% credible intervals)

Covariate effects on incidence and detectability

Coefficients of the covariates included in the four candidate hierarchical binomial mixture models are presented in the Additional file and the coefficients for the best fitting model are presented in Table 2. Our methodological approach enabled us to present predictors of incidence and CDR separately.

Table 2.

Predictors of incidence, and case detection rate in the binomial mixture model

| Coefficient, median (95% CrI) | Odds*, Odds ratio (95% CrI) | |

|---|---|---|

| State-space model | ||

| β0 (intercept) | −5.5 (−6.1, −4.9) | 0.004 (0.002, 0.007)* |

| β1 (population density)a | 0.1 (0.1, 0.14) | 1.1 (1.1,1.2) |

| β2 (temporal lag)b | 0.003 (−0.1, 0.1) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) |

| β3 (spatial lag)b | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) | 1.6 (1.4, 2.0) |

| Case detection model | CDR, median (95% CrI) | |

| CDR in kebeles with no health facility | 0.59 (0.55, 0.63) | |

| CDR in kebeles with a health facility | 0.69 (0.62, 0.77) | |

a Population per square km, b: number of incident TB cases/100,000 population/year

CDR- case detection rate

As shown in Table 2, TB incidence rate was positively associated with population density and spatial lag in the geographically adjacent sites. An increase of 10/100,000/year in average TB incidence in adjacent kebeles predicted a 5.0/100,000/year increment in TB incidence in an index kebele. Similarly, an increase of population size by 10 per square kilometre predicted an increase in TB incidence by 1/100,000/year. Population density remained a significant predictor of TB incidence in all candidate models (Additional file 2). All the models except the covariate only model demonstrated the statistically significant effect of incidence at neighbouring locations. In the best fitting model, TB incidence was not significantly related to incidence at a temporal lag of one year (Table 2).

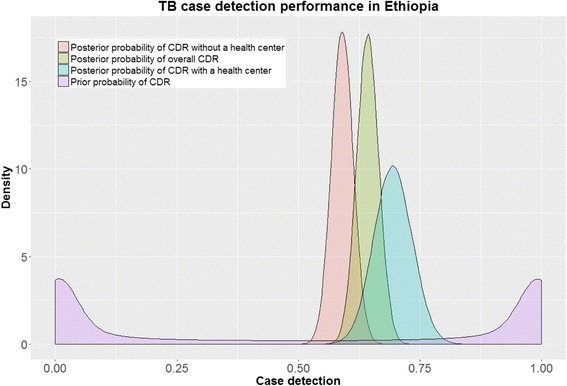

On the other hand, CDR was related to the presence of a health facility in the best fitting model, as well as in all other candidate models considered in this study. The estimated case detection rate in kebeles with no health facility was 59% (95% CrI: 55, 63), while the rate was 69% (95% CrI: 62, 77) in kebeles with a health facility.

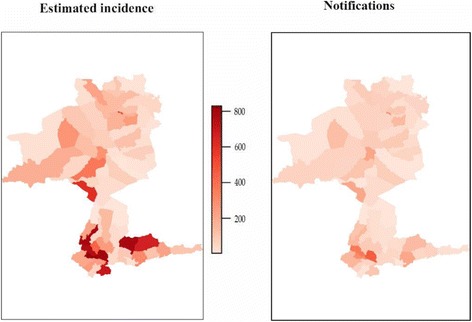

Spatial distribution

Maps of the spatial distribution of estimated incidence and notification rates of TB presented in Fig. 2 revealed the presence of undetected TB cases at kebele level in Sheka Zone. The patterns observed in the maps of incidence and notifications appeared broadly correlated. However, the incidence map shows areas of considerably greater burden and identifies new, previously unrecognised areas of high burden. The incidence map identified many rural kebeles without a health facility and urban kebeles as high burden locations, in contrast to the notification map that identified mainly urban kebeles. These locations corresponded to kebeles with high population density and were surrounded by high incidence kebeles. The maps illustrate that estimated incidence rates are higher than notification rates, highlighting that notification data markedly underestimate incidence.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of spatial distribution of model estimated TB incidence and notifications per 1,000,000, Sheka Zone, Ethiopia, 2010–2014

Goodness of fit of the model

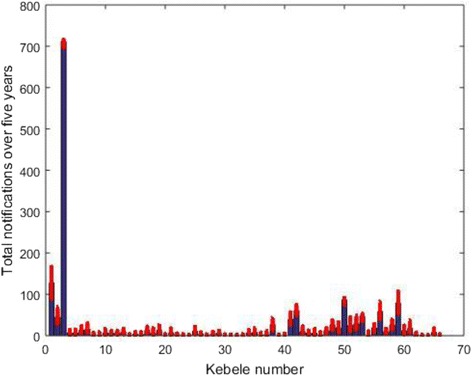

We calculated a Bayesian P-value by comparing a Pearson chi-square for both the simulated datasets and the actual dataset. The proportion of times the discrepancy measure for simulated data is greater than the actual data (a Bayesian P-value) from a posterior predictive check was 0.40. The Bayesian P-value suggests that the model fits the observed data satisfactorily [15, 18]. As an internal validity check, we simulated using posterior parameter values whether our model could reproduce the notification data that were previously used to estimate the model parameters. Comparison of notification data with simulated data indicated a close fit (Fig. 3). In addition, comparison of priors with their posteriors also indicated that our estimates were entirely data-driven (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the observed (notifications) (in blue) and the simulated notifications (in red). All the chains in the simulated data are plotted as dots

Fig. 4.

Comparison of prior and posterior probabilities of case detection rate (CDR)

Discussion

The Bayesian hidden Markov model approach used in this study provided a means to estimate both TB incidence and case detection rate, and identified previously unrecognised TB hotspots in rural Ethiopia. To our knowledge, this is the first report applying spatially explicit binomial mixture methods to estimate TB incidence and case detection using only case notifications distributed over space and time.

By using Bayesian inference, we were able to incorporate the spatial dependence structure, random effects and a hidden state (true TB incidence) into our model. The improved fit achieved by including a geospatial term highlights the importance of accounting for spatial correlation in TB studies [8]. In this study, incorporation of the spatial dependence structure changed estimated relationships between covariates and incidence: some relationships changed from significant to non-significant, while others remained significant but with reduced precision. Like others [19, 20], we conclude that failing to account for spatial effects may lead to inflated regression coefficients and spuriously narrow credible intervals.

In contrast to previous analyses that described patterns in the notified cases (as a proxy for incidence) [7, 8], our model explicitly separated the true incidence (hidden state) and observation process (case detection). A high or increasing notification rate could reflect either an efficient health system rapidly diagnosing all incident cases or a poor health system failing to detect patients quickly enough to gain control of the epidemic. As these two phenomena lie at opposite poles of programmatic TB control and would be associated with profoundly different case detection rates, it is critical to distinguish them objectively and without the need for opinion-based estimates of case detection [21].

Applied to five years of TB surveillance data in Sheka Zone Ethiopia, our model demonstrated a wide discrepancy between the estimated incidence rate and notification rate in areas with no health centres, which is consistent with WHO estimates [22, 23], highlighting the importance of strengthening surveillance systems to reduce missed cases [23, 24]. Unlike the WHO estimates, however, we estimated that the incidence of tuberculosis is increasing, and that increased notification rates reflect both increased detection and increased incidence.

The estimated TB incidence in this study is highly spatially heterogeneous, replicating previous reports [10, 20, 25], and associated with average incidence in the neghbouring kebeles (spatial lag) and population density, reflecting an extended duration of contact between individuals as a driver of TB epidemiology in high-burden settings [26, 27]. In contrast, TB incidence at a temporal lag of one year in this study failed to replicate the statistically significant association observed in the previous analysis using GLMs [10].

In our study, health facility availability predicted high TB case detection. Higher notification rates in some of the studied kebeles were attributable to both underlying higher incidence and higher case detection in the setting of health facility availability.

In contrast to methods used by WHO to estimate TB incidence, our approach uses only routinely collected surveillance data and does not incorporate costly prevalence surveys and expert opinion regarding CDR, which is criticized for its insensitivity to recent changes and the potential for bias [1]. Expert opinion is a potentially important strategy to use in a Bayesian models where information is lacking, but has a recognised limitations in accurate adjustment of disease estimates [3] and is widely considered the lowest standard of empirical evidence [28]. In addition, it does not exist at fine geographical levels, such as the one we are assessing here, and so is impractical to use in this context. Hence, our approach uses expert opinion only for the purpose of developing a vague prior probability distribution. We aim to improve on expert opinion through the use of the structured hidden Markov Model and so to develop a feasible alternative approach that can be used for regular monitoring of TB incidence and is reactive to recent changes.

Our case detection model assumes that individual TB cases are detected at a fixed rate and independently (conditional on a given incidence). This assumption may not be valid in the case of concerted efforts at contact tracing. However, as contact tracing is not systematically implemented in Ethiopia, the proportion of cases in our study arising from contact tracing would be small and this assumption would be a minor consideration. Moreover, we included a random effect term (ɷij) in our model to allow for changes in detection rate over place and time. Sparse data were accounted for by including random effects to explain extra-model variability. Further work is in progress to build models that account for over dispersion, which may arise from non-independent detections of individuals.

Conclusions

By using Binomial mixture models, we were able to investigate different epidemiological questions related to the size, trend and predictors of TB incidence and CDR. Our model demonstrated a wide discrepancy between incidence rate and notification rates, and identified previously unrecognised TB hotspots in rural Ethiopia, but was broadly consistent with official estimates. This approach provides an alternative approach to estimating incidence, entirely independent of the methods involved in current case detection rate estimates and is feasible to perform from routinely collected surveillance data.

Additional files

Model code. (DOCX 14 kb)

Outputs from Candidate Models. (DOCX 21 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sheka Zone Health Department, Ethiopia, and all health centres for permission to access the data; and the Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency, Ethiopia, for the provision of kebele polygons. The authors are grateful to Mr.Tamrat Shaweno, Mr. Elesa Moges and Mr. Sewnet Dasho for data collection and coordination.

Availability of data and materials

The spatial data that support the findings of this study were made available by the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) of Ethiopia, and so are not publicly available. The code required to run the above analysis using R2WinBUGS library is provided as an additional file.

Abbreviations

- CDR

Case detection rate

- CrI

Credible Interval

- DIC

Deviance information criteria

- TB

Tuberculosis

Authors’ contributions

DS and EM wrote the code in WinBUGS, DS drafted the initial study concept and EM, JD & JT refined this further. DS wrote the initial draft of this manuscript, and all authors provided input into revisions and approved the final draft and submission for publication.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Melbourne University Health Sciences Human Ethics Subcommittee, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, and the Zonal Health Department, Sheka Zone, Masha, Ethiopia.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12879-017-2759-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Debebe Shaweno, Email: debebesh@gmail.com.

James M. Trauer, Email: james.trauer@monash.edu

Justin T. Denholm, Email: justin.denholm@mh.org.au

Emma S. McBryde, Email: emma.mcbryde@jcu.edu.au

References

- 1.Avilov KK, Romanyukha AA, Borisov SE, Belilovsky EM, Nechaeva OB, Karkach AS. An approach to estimating tuberculosis incidence and case detection rate from routine notification data. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19(3):288–294. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.14.0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glaziou P, Sismanidis C, Zignol M, Floyd K. Methods used by WHO to estimate the global burden of TB disease. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2016. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.s

- 4.Borgdorff MW. New Measurable Indicator for Tuberculosis Case Detection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(9):1523–1528. doi: 10.3201/eid1009.040349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Touray K, Adetifa I, Jallow A, Rigby J, Jeffries D, Cheung Y, Donkor S, Adegbola R, Hill P. Spatial analysis of tuberculosis in an urban west African setting: is there evidence of clustering? Tropical Med Int Health. 2010;15(6):664–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maciel ELN, Pan W, Dietze R, Peres RL, Vinhas SA, Ribeiro FK, Palaci M, Rodrigues RR, Zandonade E, Golub JE. Spatial patterns of pulmonary tuberculosis incidence and their relationship to socio-economic status in Vitoria, Brazil. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14(11):1395–1402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Randremanana RV, Richard V, Rakotomanana F, Sabatier P, Bicout DJ. Bayesian mapping of pulmonary tuberculosis in Antananarivo, Madagascar. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:21–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Souza WV, Carvalho MS, Albuquerque Mde F, Barcellos CC, Ximenes RA. Tuberculosis in intra-urban settings: a Bayesian approach. Tropical Med Int Health. 2007;12(3):323–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kéry M, Schaub M. Bayesian population analysis using WinBUGS: a hierarchical perspective. Oxford: Academic Press; 2012.

- 10.Shaweno D, Shaweno T, Trauer J, Denholm J, McBryde E. Heterogeneity of distribution of tuberculosis in Sheka Zone, Ethiopia: drivers and temporal trends. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2017;21(1):79–85. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.16.0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang X, Clements AC, Williams G, Mengersen K, Tong S, Hu W. Bayesian estimation of the dynamics of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza transmission in Queensland: A space–time SIR-based model. Environ Res. 2016;146:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lawson AB. Statistical methods in spatial epidemiology. 2nd ed. England: Wiley; 2013.

- 13.Kéry M, Royle JA. Hierarchical Bayes estimation of species richness and occupancy in spatially replicated surveys. J Appl Ecol. 2008;45(2):589–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2007.01441.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.K’ery M, Royle A. Inference About Species Richness and Community Structure Using Species-Specific Occupancy Models in the National Swiss Breeding Bird Survey MHB. In: Modeling Demographic Processes in Marked Populations. Volume 3, edn. Edited by Patil GP, Gregoire TG, Lawson AB, Nussbaum BD. Newyork, NY: Springer; 2009:639–656.

- 15.Kéry M. Introduction to WinBUGS for ecologists: Bayesian approach to regression, ANOVA, mixed models and related analyses. Oxford: Academic Press; 2010.

- 16.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2015. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015.

- 17.Martin J, Royle JA, Mackenzie DI, Edwards HH, Kery M, Gardner B. Accounting for non-independent detection when estimating abundance of organisms with a Bayesian approach. Methods Ecol Evol. 2011;2(6):595–601. doi: 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00113.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gelman A, Carlin JB, Stern HS, Rubin DB. Bayesian data analysis. FL, USA: Chapman & Hall/CRC Boca Raton; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Clements ACA, Lwambo NJS, Blair L, Nyandindi U, Kaatano G, Kinung'hi S, Webster JP, Fenwick A, Brooker S. Bayesian spatial analysis and disease mapping: tools to enhance planning and implementation of a schistosomiasis control programme in Tanzania. Tropical Med Int Health. 2006;11(4):490–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Congdon P. Spatiotemporal Frameworks for Infectious Disease Diffusion and Epidemiology. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:1261. doi:10.3390/ijerph13121261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Strengthening Health systems to stop TB: A People-centered Approach. https://www.msh.org/resources/strengthening-health-systems-to-stop-tb-a-people-centered-approach. Accessed 3 June 2016.

- 22.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2013. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

- 23.Gains in tuberculosis control at risk due to 3 million missed patients and drug resistance. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/tuberculosis-report-2013/en/. Accessed 2 Feb 2017. [PubMed]

- 24.Claassens M, Jacobs E, Cyster E, Jennings K, James A, Dunbar R, Enarson D, Borgdorff M, Beyers N. Tuberculosis cases missed in primary health care facilities: should we redefine case finding? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(5):608–614. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dowdy DW, Golub JE, Chaisson RE, Saraceni V. Heterogeneity in tuberculosis transmission and the role of geographic hotspots in propagating epidemics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(24):9557–9562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203517109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Health Organization . WHO policy on TB infection control in health-care facilities, congregate settings and households. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Classen CN, Warren R, Richardson M, Hauman JH, Gie RP, Ellis JH, van Helden PD, Beyers N. Impact of social interactions in the community on the transmission of tuberculosis in a high incidence area. Thorax. 1999;54(2):136–140. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donaldson SI, Christie CA, Mark MM. What counts as credible evidence in applied research and evaluation practice?. USA: Sage; 2009.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Model code. (DOCX 14 kb)

Outputs from Candidate Models. (DOCX 21 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The spatial data that support the findings of this study were made available by the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) of Ethiopia, and so are not publicly available. The code required to run the above analysis using R2WinBUGS library is provided as an additional file.