Abstract

Tumor suppressor candidate 2 (Tusc2, also known as Fus1) regulates calcium signaling, and Ca2+-dependent nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) pathways, which play roles in osteoclast differentiation. However, the role of Tusc2 in osteoclasts remains unknown. Here, we report that Tusc2 positively regulates the differentiation of osteoclasts. Overexpression of Tusc2 in osteoclast precursor cells enhanced receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL)-induced osteoclast differentiation. In contrast, small interfering RNA-mediated knockdown of Tusc2 strongly inhibited osteoclast differentiation. In addition, Tusc2 induced the activation of RANKL-mediated NF-κB and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase IV (CaMKIV)/cAMP-response element (CRE)-binding protein CREB signaling cascades. Taken together, these results suggest that Tusc2 acts as a positive regulator of RANKL-mediated osteoclast differentiation.

Keywords: Calcium signaling, NF-κB, Osteoclasts, RANKL, Tumor suppressor candidate 2

INTRODUCTION

Bone is a dynamic organ which is continuously maintained by a balance between osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Osteoclasts are specialized cells derived from monocyte/macrophage hematopoietic progenitor cells (1, 2). Osteoclasts, which have bone-resorbing activity, are large multinucleated cells located on the trabecular and endosteal cortical bone surfaces (3). Meanwhile, osteoblasts, which synthesize and mineralize new bone, are derived from the mesenchymal lineage (4).

Receptor activator of nuclear factor κB ligand (RANKL), a member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily, is an essential factor for osteoclast differentiation. Binding of RANKL to its receptor RANK activates nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), such as c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and p38 MAPKs, which are involved in osteoclast differentiation (1, 2, 5). The RANKL-RANK interaction activates the nuclear factor of activated T-cells c1 (NFATc1), the master regulator of osteoclastogenesis (5, 6). Overexpression of NFATc1 induces osteoclast differentiation without RANKL stimulation (7–9). NFATc1 induces the expression of osteoclast-specific genes, including osteoclast-associated receptor (OSCAR), cathepsin K, and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), which mediate the differentiation and functions of osteoclasts (5, 7, 8).

Calcium (Ca2+) serves as a ubiquitous second messenger and is crucial for bone homeostasis (10). Ca2+ signaling also regulates proliferation, differentiation, transcription, activation, and apoptosis in bone cells, including osteoclasts, osteoblasts, and osteocytes (11). RANKL induces Ca2+ signaling in osteoclasts via calmodulin (CaM), an intracellular Ca2+ receptor (12). On the binding of Ca2+, CaM activates calcineurin and a calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase (CaMK), resulting in the activation and induction of NFATc1 (11, 13). Calcineurin is a Ca2+ and calmodulin-dependent serine/threonine protein phosphatase. Calcineurin dephosphorylates NFATc1, which allows nuclear translocation of NFATc1, thereby promoting osteoclastogenesis (11). CaMKs are important downstream mediators of the Ca2+ signaling pathway in osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption (14, 15). CaMKIV activates its downstream cAMP-response element (CRE)-binding protein (CREB), which induces the expression of NFATc1 and osteoclast-specific genes. Thus, Ca2+-related signal events are crucial for osteoclast differentiation and function.

Tumor suppressor candidate 2 (Tusc2), also known as Fus1, is a 110 amino acid mitochondrial protein. Tusc2 acts as a tumor suppressor and it is expressed in various tissues, such as the heart, kidney, liver, bone marrow, and lung. Tusc2 is frequently deleted in cancers, including lung cancer (16), mesotheliomas (17), and bone and soft tissue sarcomas (18). Uzhachenko et al. reported that Tusc2 is a novel regulator of mitochondrial Ca2+ handling and calcium-dependent mitochondrial and cellular functions (19). Tusc2 loss in activated CD4+ T cells decreased the activation of NFAT/NF-κB-dependent pathways (19). Although Tusc2 regulates NFAT and NF-κB signaling, which are important for osteoclast differentiation, the role of Tusc2 in bone cells has not yet been described.

In this study, we investigated the role of Tusc2 in osteoclasts. We observed that Tusc2 could enhance RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation via NF-κB activation. Moreover, we showed that Tusc2 promotes the activation of the CaMKIV-CREB signaling pathway. Taken together, our results suggested that Tusc2 acts as a positive regulator of RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation.

RESULTS

Overexpression of Tusc2 enhances RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation

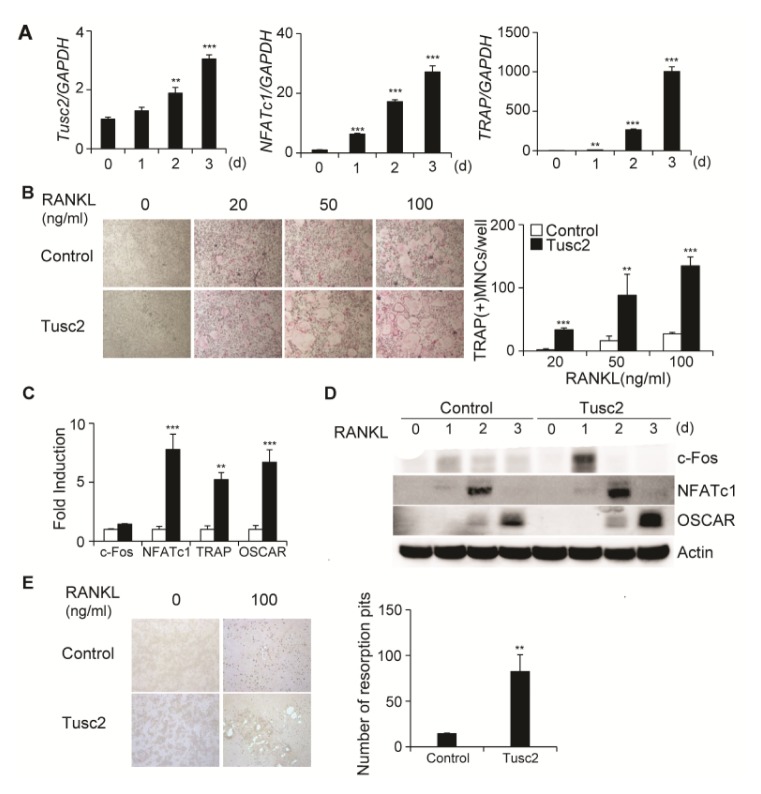

First, we examined whether Tusc2 is expressed in osteoclast lineage cells using real-time PCR analysis. BMMs were cultured with M-CSF and RANKL for 3 days to induce osteoclast differentiation. RANKL induced the expression of NFATc1, which is a key transcription factor in osteoclast differentiation. The induction of NFATc1 was followed by the expression of TRAP, which is an osteoclast marker gene (Fig. 1A). Expression of Tusc2 increased gradually during RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Overexpression of Tusc2 in bone marrow-derived macrophage-like cells (BMMs) enhances RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. (A) BMMs were cultured with M-CSF and RANKL for the indicated times. The mRNA levels of Tusc2, NFATc1, and TRAP were assessed by quantitative real-time PCR. **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 versus the control. (B) BMMs were transduced with pMX-IRES-EGFP (control) or Tusc2 retrovirus, and cultured in the presence of M-CSF and various concentrations of RANKL for 3 days. Cultured cells were stained for TRAP (left panel). The TRAP-positive multinucleated cells (MNCs) per well were counted (right panel). **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 versus the control. (C, D) BMMs were transduced with pMX-IRES-EGFP (control) or Tusc2 retrovirus and cultured in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL for the indicated times. (C) The mRNA levels of c-Fos, NFATc1, TRAP, and OSCAR were assessed by quantitative real-time PCR. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate samples. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 versus the control. (D) Cell lysates were harvested from cultured cells and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (E) Transfected BMMs were cultured with M-CSF alone or M-CSF and RANKL on inorganic crystalline calcium phosphate plates. Resorption lacunae were visualized by bright-field microscopy. **P < 0.01 versus the control.

To investigate the role of Tusc2 in RANKL-mediated osteoclast differentiation, we retrovirally overexpressed Tusc2 in BMMs. Transduced BMMs were cultured with various concentrations of RANKL in the presence of M-CSF for 3 days, and cultured samples were stained for TRAP (Fig. 1B). Overexpression of Tusc2 in BMMs significantly enhanced RANKL-mediated osteoclast differentiation and strongly promoted the formation of TRAP-positive multinucleated cells (MNCs) compared with that in control cells (Fig. 1B). These results suggested that Tusc2 expression in the osteoclast lineage contributed to osteoclast differentiation.

We next examined which osteoclast-specific genes are regulated by overexpression of Tusc2 during osteoclast differentiation. Compared with the control, overexpression of Tusc2 increased the expressions of c-Fos and NFATc1, and downstream target genes such as TRAP and OSCAR (Fig. 1C). We also confirmed the effect of Tusc2 on the protein levels of these genes by western blot analysis. Overexpression of Tusc2 increased the protein levels of c-Fos, NFATc1, TRAP, and OSCAR (Fig. 1D). These data suggested that Tusc2 plays a role in RANKL-mediated osteoclast differentiation via regulating the expression of c-Fos and NFATc1.

Next, we determined whether overexpression of Tusc2 affected bone resorption. Transduced BMMs were cultured on Osteo assay plates in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL for 5 days. The bone-resorbing ability of Tusc2-overexpressing osteoclasts was significantly increased compared with that in the control (Fig. 1E). Collectively, these results indicated that Tusc2 regulates RANKL-mediated osteoclast differentiation.

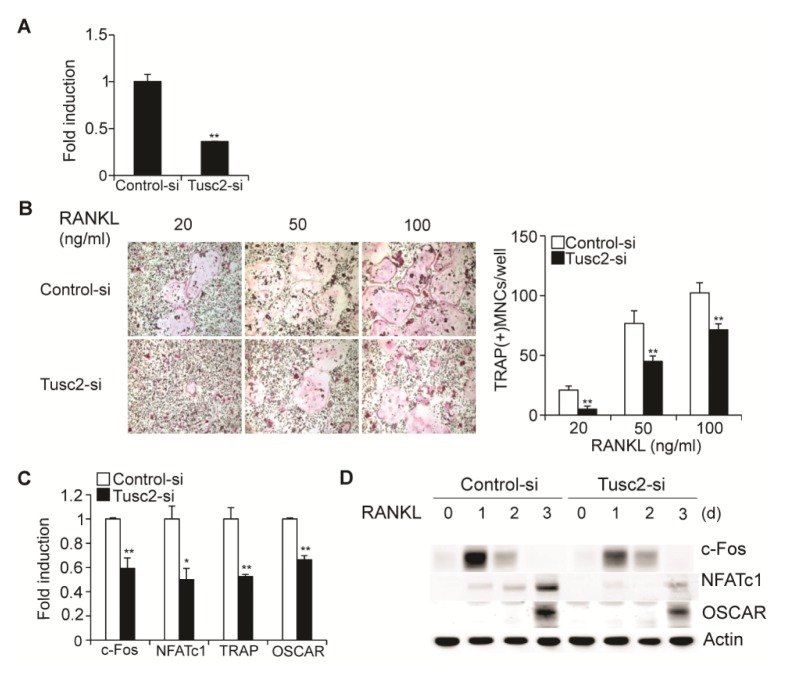

Downregulation of Tusc2 attenuates RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation

We investigated the physiological role of Tusc2 in osteoclast differentiation using small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of Tusc2. Upon transfection with a Tusc2-specific siRNA, the expression of Tusc2 was dramatically reduced in BMMs (Fig. 2A). Downregulation of Tusc2 significantly reduced RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation and attenuated the formation of TRAP-positive MNCs compared with that in the control cells (Fig. 2B). We then examined the expression levels of osteoclast marker genes such as c-Fos, NFATc1, TRAP, and OSCAR during osteoclast differentiation using real-time PCR and western blot analysis. As expected, downregulation of Tusc2 suppressed the mRNA and protein levels of osteoclast marker genes (Fig. 2C, D). These results indicated that Tusc2 plays a positive role in RANKL-mediated osteoclast differentiation.

Fig. 2.

Knockdown of Tusc2 in bone marrow-derived macrophage-like cells (BMMs) attenuates RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. (A) BMMs were transfected with control or Tusc2 siRNAs. The mRNA levels of Tusc2 were assessed by quantitative real-time PCR. Data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate samples. **P < 0.01 versus the control. (B) Transfected BMMs were cultured in the presence of M-CSF and various concentrations of RANKL for 3 days. Cultured cells were stained for TRAP (left panel). The number of TRAP-positive multinucleated cells (MNCs) per well were counted (right panel). **P < 0.01 versus the control. (C, D) Transfected BMMs were cultured in the presence of M-CSF and RANKL for the indicated times. (C) The mRNA levels of c-fos, NFATc1, and TRAP were assessed by quantitative real-time PCR. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate samples. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus the control. (D) Cell lysates were harvested from cultured cells and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies.

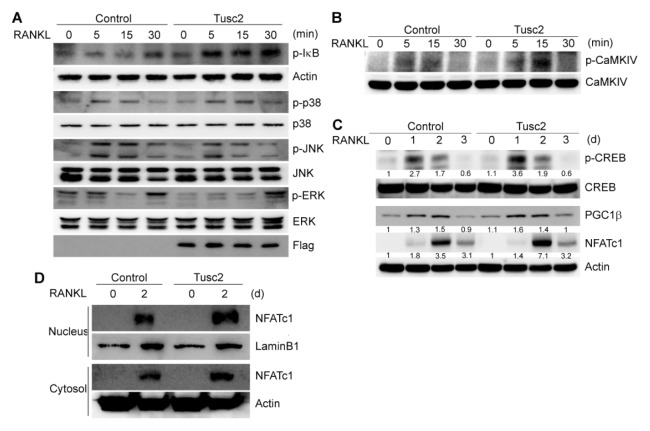

Overexpression of Tusc2 increases RANKL-induced NF-κB and CaMKIV-CREB activation

RANKL activates multiple signaling pathways, including NF-κB, p38, JNK, and ERK, which are essential for osteoclast differentiation. Tusc2 enhanced RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation; therefore, we investigated the effect of Tusc2 on RANKL-induced early signaling pathways. BMMs were infected with control and Tusc2 retroviruses, respectively. Consistent with previous results (5, 20), RANKL induced the phosphorylation of IκB, p38, JNK, and ERK (Fig. 3A). Overexpression of Tusc2 strongly enhanced RANKL-induced IκB phosphorylation, whereas other signaling pathways, such as p38, JNK, and ERK, were not affected or even attenuated (Fig. 3A). These results indicated that Tusc2 plays a role in RANKL-induced NF-κB activation.

Fig. 3.

Overexpression of Tusc2 in bone marrow-derived macrophage-like cells (BMMs) enhances RANKL-induced NF-κB activation and CaMKIV/CREB signaling. (A) Bone marrow-derived macrophage-like cells (BMMs) were transduced with control or Tusc2 retrovirus. Transduced BMMs were serum-starved for 6 hours and stimulated with RANKL for the indicated times. Whole cell lysates were then harvested from the cultured cells and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (B, C) BMMs were transduced with control or Tusc2 retrovirus. Transduced BMMs were serum-starved for 6 hours and stimulated with RANKL for the indicated durations. Whole cell lysates were then harvested from the cultured cells and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (D) BMMs were transduced with pMX-IRES-EGFP (control) or Tusc2 retrovirus and cultured for 2 days with M-CSF and RANKL. Cytoplasmic fractions and nuclear fractions were harvested from cultured cells and immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. Antibodies for actin and lamin B1 were used for the normalization of cytoplasmic and nuclear extracts, respectively.

Ca2+ serves as a second messenger and mediates its own signaling through Ca2+-binding proteins during osteoclast differentiation (21). The Ca2+/CaMKIV/CREB pathway is important for osteoclast differentiation and function (13). Tusc2 is a Ca2+-binding protein that has a Ca2+-binding domain (the EF-hand) (19); therefore, we investigated the role of Tusc2 in RANKL-induced Ca2+ signaling cascades. Overexpression of Tusc2 increased the activation of CaMKIV after RANKL stimulation, as shown by its phosphorylation status (Fig. 3B). CaMKIV activates CREB through phosphorylation during osteoclast differentiation. Compared with the control, overexpression of Tusc2 enhanced the activation of CREB during RANKL-mediated osteoclast differentiation (Fig. 3C). In addition, activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1β (PGC1β), a target of CREB, was increased by Tusc2 overexpression. The expression of NFATc1 was increased when Tusc2 was overexpressed during osteoclast differentiation (Fig. 3C). Taken together, these results indicated that Tusc2 positively regulates the CaMKIV-CREB pathway during RANKL-mediated osteoclast differentiation.

RANKL-induced Ca2+ signaling regulates NFATc1 by activating the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent phosphatase calcineurin (10). Dephosphorylation of NFATc1 by calcineurin leads to nuclear translocation of NFATc1, thereby promoting osteoclast differentiation (10). Next, we determined the localization of NFATc1 during osteoclast differentiation. Overexpression of Tusc2 induced enrichment of NFATc1 in the nuclear region of osteoclasts (Fig. 3D). These results indicated that Tusc2 activates the CaMKIV/CREB signaling pathway and enhances the nuclear localization of NFATc1 during RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation.

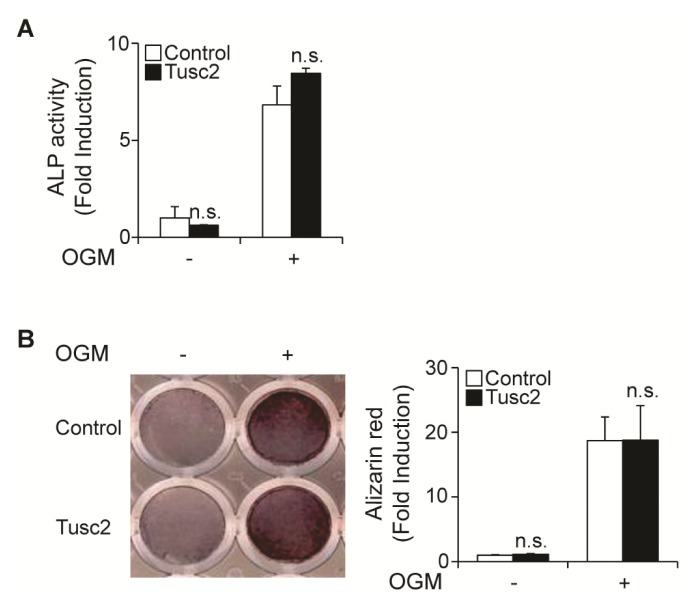

Tusc2 overexpression does not affect osteoblast differentiation and function

Next, we examined whether Tusc2 has an effect on osteoblast differentiation. To test this assumption, we cultured primary osteoblast precursor cells infected with an empty retroviral vector or a vector containing Tusc2 in an osteogenic medium (OGM) containing BMP2, ascorbic acid, and β-glycerophosphate. There was no difference in the alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity between the control vector and Tusc2-infected osteoblasts (Fig. 4A). We then evaluated the effect of Tusc2 on osteoblast function using mineralized nodule staining. Nodule formation in the Tusc2-infected osteoblasts was comparable to that in the control vector-infected cells (Fig. 4B). Therefore, these results indicated that Tusc2 does not affect osteoblast differentiation and function.

Fig. 4.

Overexpression of Tusc2 has no effect on osteoblast differentiation and function. (A, B) Osteoblasts were transduced with pMX-IRES-EGFP (control) or Tusc2 retrovirus and cultured in an osteogenic medium (OGM) containing BMP2, ascorbic acid, and β-glycerophosphate. (A) Cells cultured for 3 days were subjected to an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity assay. ALP activity was measured as change in the absorbance at 405 nm. (B) Cells cultured for 9 days were fixed and stained for alizarin red (left panel), which was quantified by densitometry at 562 nm (right panel). n.s., not significant.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we report a novel role of Tusc2 in RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. Overexpression of Tusc2 in BMMs significantly enhanced RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. Ectopic expression of Tusc2 in BMMs also increased the expression of osteoclast-related genes, including NFATc1, TRAP, and OSCAR. Conversely, knockdown of Tusc2 using siRNA in BMMs inhibited osteoclast differentiation. Thus, we concluded that Tusc2 is involved in RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation.

Tusc2 is a Ca2+/myristoyl switch protein that has a Ca2+-binding domain and an N myristoylation domain (19). Tusc2 acts by elevating Ca2+, leading to Ca2+ accumulation in mitochondria, which is a major component of Ca2+ signals (22). Calcium serves as a signaling molecule that regulates osteoclast differentiation and function (23). These results suggested that Tusc2 plays a role in osteoclast differentiation by regulating the calcium signaling pathway.

The activation of NF-κB and NFAT pathways was reduced in Fus1-deficient T cells (19). NF-κB is an important transcription factor that induces the expression of NFATc1 during osteoclast differentiation. Several papers have reported that NF-κB is essential for RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. The disruption of the p50 and p52 subunits of NF-κB resulted in impaired osteoclast differentiation, accompanied by an osteopetrotic phenotype (24). Takatsuna et al. reported that dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin (DHMEQ), an NF-κB inhibitor, inhibited osteoclast differentiation by downregulating NFATc1 (25). Consistent with these results, NF-κB components p50 and p65 are recruited to the NFATc1 promoter in response to RANKL (26). In addition, Ca2+ signaling activates the NF-κB pathway in various cell lines. Ca2+ signals activate NF-κB and NFAT, two transcription factors important for T cell activation (27). Ca2+ plays a crucial role in the activation of NF-κB in cerebellar granule neurons and airway epithelial cells (28, 29). Increased cytosolic Ca2+ leads to phosphorylation of IκB and activation of NF-κB (30).

In this study, we demonstrated that Tusc2 increased IκB phosphorylation and NFATc1 induction in response to RANKL. Phosphorylation of IκB leads to its degradation by the proteasome, which is important for p65 translocation into the nucleus and induction of NFATc1 expression (31). These results suggested that Tusc2 might enhance NF-κB activation through Ca2+ signaling, resulting in enhanced osteoclast differentiation.

Intracellular Ca2+ initiates NFATc1 activation and Ca2+/CaM-mediated signaling events that regulate osteoclast differentiation and function (13). CaMK is a major downstream component of Ca2+ signaling and it is involved in osteoclast differentiation (26). Specific CaMK inhibitors, KN-62 and KN-63, disrupt osteoclast differentiation (14). CREB, a target of CaMKIV, interacts with NFATc1 (32). In addition, knockdown of CREB decreased NFATc1 expression (32). The CaMKIV/CREB pathway enhances induction of NFATc1 and NFATc1 downstream genes, and subsequently promotes osteoclastic bone resorption (13). We observed that Tusc2 enhanced the activity of the CaMKIV-CREB signaling pathway. These data suggested that Tusc2 activates a Ca2+-mediated CaMKIV/CREB signaling cascade during osteoclast differentiation.

RANKL-induced Ca2+ signals have a crucial role in the activation of NFATc1 in BMMs. The calcium chelator, BAPTAAM (a calcium-specific aminopolycarboxylic acid), suppresses RANKL-induced NFATc1 expression (9). Leflunomide blocks osteoclast differentiation through inhibition of expression of NFATc1 by inhibiting Ca2+ (14). Ca2+-bound calmodulin activates calcineurin, which dephosphorylates NFATc1 and translocates NFATc1 to the nucleus (10). We observed that Tusc2 activated the CaMKIV/CREB signaling pathway and induced nuclear localization of NFATc1 during RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. Thus, our data suggested that increased Ca2+ accumulation by Tusc2 affects the expression and localization of NFATc1 via activation of CaMKIV/CREB.

In conclusion, we identified Tusc2 as a positive regulator of RANKL-induced osteoclast differentiation. Tusc2 enhanced osteoclast differentiation via activation of NF-κB and CaMKIV/CREB signaling cascades. Further studies examining the detailed mechanisms underlying Tusc2 regulation will provide a clearer understanding of the roles of Tusc2 and its potential as a therapeutic target for bone diseases such as osteoporosis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

All materials and methods are shown in online supplementary data.

Osteoclast differentiation

Murine osteoclasts were prepared from bone marrow cells as described previously (33). Bone marrow cells were isolated from tibiae and femurs of 6–8 week old Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) mice by flushing the bone marrow with α-minimal essential medium (α-MEM). The cells were cultured in α-MEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) with M-CSF (30 ng/ml) for 3 days. Floating cells were removed and adherent cells [bone marrow-derived macrophage-like cells (BMMs)] were used as osteoclast precursors. To generate osteoclasts, BMMs were cultured with M-CSF (30 ng/ml) and RANKL (20–100 ng/ml) for 3 days. Cultured cells were fixed and stained for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP). TRAP-positive cells with more than three nuclei were counted as osteoclasts.

Osteoblast differentiation

Primary osteoblasts were isolated from neonatal mouse calvaria by successive enzymatic digestion with 0.1% collagenase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) and 0.2% dispase II (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Osteoblasts were cultured in an osteogenic medium (OGM) containing BMP2 (100 ng/ml), ascorbic acid (50 ng/ml), and β-glycerophosphate (100 mM). To assess their differentiation, osteoblasts cultured for 3 days were stained for alkaline phosphatase (ALP). To assess ALP activity, cells were lysed in osteoblast lysis buffer [50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA], and the lysates were incubated with p-nitrophenyl phosphate substrate (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). ALP activity was then measured at an absorbance of 405 nm. To assess their function, osteoblasts cultured for 9 days were fixed with 70% ethanol and stained with 40 mM Alizarin red in 10% cetylpyridinium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) (pH 4.2). Alizarin red staining was measured at an absorbance of 562 nm.

Fractionation and Western blot analysis

Cultured cells were harvested after washing with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and then lysed in extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet p-40, 0.01% protease inhibitor mixture). Cells were fractionated using Nuclease and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Cell lysates, cytoplasmic extracts, and nuclease extracts were subjected to SDS-PAGE and transferred electrophoretically onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane (Millipore, MA, USA). The membranes were subjected to western blot analysis and signals were detected by a LAS3000 Luminescent image analyzer (GE Healthcare, NJ, USA) (34).

Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by grants from NRF-2014R1 A1A2009740 and MRC (2011-0030132) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL. Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature. 2003;423:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nature01658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh MC, Kim N, Kadono Y, et al. Osteoimmunology: interplay between the immune system and bone metabolism. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:33–63. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teitelbaum SL. Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science. 2000;289:1504–1508. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5484.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogasawara T, Kawaguchi H, Jinno S, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 2-induced osteoblast differentiation requires Smad-mediated down-regulation of Cdk6. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6560–6568. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6560-6568.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JH, Kim N. Signaling Pathways in Osteoclast Differentiation. Chonnam Med J. 2016;52:12–17. doi: 10.4068/cmj.2016.52.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JH, Kim N. Regulation of NFATc1 in Osteoclast Differentiation. J Bone Metab. 2014;21:233–241. doi: 10.11005/jbm.2014.21.4.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim K, Kim JH, Lee J, et al. Nuclear factor of activated T cells c1 induces osteoclast-associated receptor gene expression during tumor necrosis factor-related activation-induced cytokine-mediated osteoclastogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:35209–35216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim K, Lee SH, Ha Kim J, Choi Y, Kim N. NFATc1 induces osteoclast fusion via up-regulation of Atp6v0d2 and the dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP) Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:176–185. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takayanagi H, Kim S, Koga T, et al. Induction and activation of the transcription factor NFATc1 (NFAT2) integrate RANKL signaling in terminal differentiation of osteoclasts. Dev Cell. 2002;3:889–901. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00369-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwang SY, Putney JW., Jr Calcium signaling in osteoclasts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 20111813:979–983. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hogan PG, Chen L, Nardone J, Rao A. Transcriptional regulation by calcium, calcineurin, and NFAT. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2205–2232. doi: 10.1101/gad.1102703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Racioppi L, Means AR. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase IV in immune and inflammatory responses: novel routes for an ancient traveller. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:600–607. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato K, Suematsu A, Nakashima T, et al. Regulation of osteoclast differentiation and function by the CaMK-CREB pathway. Nat Med. 2006;12:1410–1416. doi: 10.1038/nm1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ang ES, Zhang P, Steer JH, et al. Calcium/calmodul-independent kinase activity is required for efficient induction of osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption by receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL) J Cell Physiol. 2007;212:787–795. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krueger JK, Olah GA, Rokop SE, Zhi G, Stull JT, Trewhella J. Structures of calmodulin and a functional myosin light chain kinase in the activated complex: a neutron scattering study. Biochemistry. 1997;36:6017–6023. doi: 10.1021/bi9702703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prudkin L, Behrens C, Liu DD, et al. Loss and reduction of FUS1 protein expression is a frequent phenomenon in the pathogenesis of lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:41–47. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ivanova AV, Ivanov SV, Prudkin L, et al. Mechanisms of FUS1/TUSC2 deficiency in mesothelioma and its tumorigenic transcriptional effects. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:91. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li G, Kawashima H, Ji L, et al. Frequent absence of tumor suppressor FUS1 protein expression in human bone and soft tissue sarcomas. Anticancer Res. 2011;31:11–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uzhachenko R, Ivanov SV, Yarbrough WG, Shanker A, Medzhitov R, Ivanova AV. Fus1/Tusc2 is a novel regulator of mitochondrial calcium handling, Ca2+-coupled mitochondrial processes, and Ca2+-dependent NFAT and NF-kappaB pathways in CD4+ T cells. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:1533–1547. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim K, Kim JH, Youn BU, Jin HM, Kim N. Pim-1 regulates RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis via NF-kappaB activation and NFATc1 induction. J Immunol. 2010;185:7460–7466. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kajiya H. Calcium signaling in osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2012;740:917–932. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-2888-2_41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uzhachenko R, Shanker A, Yarbrough WG, Ivanova AV. Mitochondria, calcium, and tumor suppressor Fus1: At the crossroad of cancer, inflammation, and autoimmunity. Oncotarget. 2015;6:20754–20772. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takami M, Woo JT, Takahashi N, Suda T, Nagai K. Ca2+-ATPase inhibitors and Ca2+-ionophore induce osteoclast-like cell formation in the cocultures of mouse bone marrow cells and calvarial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237:111–115. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Franzoso G, Carlson L, Xing L, et al. Requirement for NF-kappaB in osteoclast and B-cell development. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3482–3496. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Takatsuna H, Asagiri M, Kubota T, et al. Inhibition of RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis by (−)-DHMEQ, a novel NF-kappaB inhibitor, through downregulation of NFATc1. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:653–662. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Asagiri M, Sato K, Usami T, et al. Autoamplification of NFATc1 expression determines its essential role in bone homeostasis. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1261–1269. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dolmetsch RE, Lewis RS, Goodnow CC, Healy JI. Differential activation of transcription factors induced by Ca2+ response amplitude and duration. Nature. 1997;386:855–858. doi: 10.1038/386855a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lilienbaum A, Israel A. From calcium to NF-kappa B signaling pathways in neurons. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:2680–2698. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.8.2680-2698.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tabary O, Boncoeur E, de Martin R, et al. Calcium-dependent regulation of NF-(kappa)B activation in cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. Cell Signal. 2006;18:652–660. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boland ML, Chourasia AH, Macleod KF. Mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer. Front Oncol. 2013;3:292. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2013.00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyce BF, Xiu Y, Li J, Xing L, Yao Z. NF-kappaB-mediated regulation of osteoclastogenesis. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2015;30:35–44. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2015.30.1.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park HJ, Baek K, Baek JH, Kim HR. The cooperation of CREB and NFAT is required for PTHrP-induced RANKL expression in mouse osteoblastic cells. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:667–679. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim K, Kim JH, Lee J, et al. MafB negatively regulates RANKL-mediated osteoclast differentiation. Blood. 2007;109:3253–3259. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-048249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song I, Jeong BC, Choi YJ, Chung YS, Kim N. GATA4 negatively regulates bone sialoprotein expression in osteoblasts. BMB Rep. 2016;49:343–348. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2016.49.6.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.